Colonoscopy is the gold standard for colorectal cancer screening.1–3 Detection and complete removal of adenomas disrupt the adenoma-carcinoma sequence and thus prevent the development of colorectal cancer. However, endoscopists still fear that they may have overlooked relevant lesions despite the availability of modern videoendoscopes. This problem is underlined by a relatively high rate of adenomas missed by conventional endoscopy (up to 27%), as determined by back to back or repeat colonoscopy studies.2,3 Furthermore, retrospective analyses have suggested that colonoscopy may even fail to detect colorectal cancer (CRC),4,5 although large multicentre studies indicated a high negative predictive value for a normal complete colonoscopy with regard to CRC (>99%).6 Therefore, the question arises of whether adenomas or CRC detected after previous colonoscopies have grown fast or were simply overlooked during initial endoscopic analysis?

Exophytic adenomas can be diagnosed easily and most of the Western endoscopists have previously focused on these polypoid lesions. In contrast, several years ago Japanese researchers described flat lesions in the colonic mucosa and classified these so-called “flat adenomas” as premalignant lesions.7,8 These lesions now can be subdivided according to their growing pattern: small flat adenoma, lateral spreading adenoma, and depressed lesions with high malignant potential.7 It is well accepted that flat lesions show only small changes in the mucosal architecture, such as small depressions and discrete changes in colour. Detection of such subtle mucosal changes during conventional colonoscopy remained a challenge, even for experienced endoscopists. Recently, using dye spraying techniques, chromoendoscopy has revolutionised the detection of flat lesions in the colonic mucosa and, when used in a targeted fashion, allows the unmasking of the type of lesion and its borderlines. Furthermore, the use of magnifying endoscopes during chromoendoscopy allows a detailed surface analysis of suspected lesions and prediction of the dignity of the lesions using the so-called pit pattern classification (see fig 1 ▶). These features of magnifying chromoendoscopy may also offer the possibility of achieving appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic decisions during ongoing colonoscopies (for example, biopsy, polypectomy, and mucosal resection versus surgery).

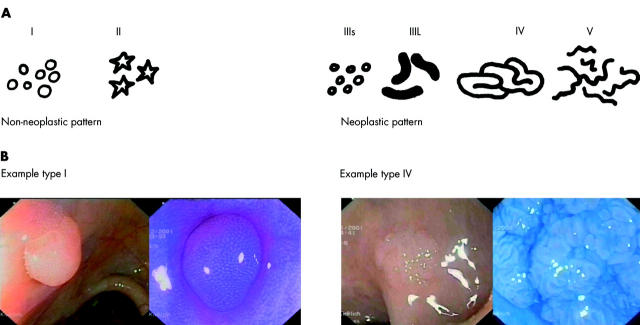

Figure 1.

Pit pattern classification according to Kudo and colleagues.16. The typical crypt architecture of types I–V are indicated (A). (B) Examples of type I (left) and type IV (right) lesions before and after chromoendoscopy.

Depressed lesions can lead to early malignant invasion, even when small in size. For a long time these lesions were frequently not recognised by Western endoscopists. However, Fujii and colleagues9 impressively demonstrated that detection of depressed early colorectal malignancies was possible with the help of chromoendoscopy and magnification endoscopy in the UK. This first observation was confirmed by Rembacken and colleagues.10 After training in chromo- and magnifying endoscopy, the investigators showed that in 1000 patients, 117 flat and two depressed lesions among 321 adenomas could be diagnosed. Similar results were seen by Saitoh and colleagues11 where American and Japanese endoscopists performed team colonoscopies in 211 American patients and stained parts or the whole colon with indigo carmine. In 23% of cases, flat lesions or flat lesions with depressions were diagnosed. Most of these lesions (82%) were adenomatous. In conclusion, these data show clearly that intravital staining techniques allow significantly improved detection and analysis of flat lesions and should be part of the endoscopist’s armamentarium.12 The endoscopist should be aware of diminutive mucosal alterations and stain in a targeted fashion, thereby reducing the additional time required to perform magnifying chromoendoscopy and increasing the diagnostic yield for screening colonoscopy in CRC.

In this issue of Gut, Rutter and colleagues13 describe the higher sensitivity of pancolonic chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasias in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis (UC) [see page 256]. The collective of patients with UC is ideal for intravital staining. Patients with chronic active UC have an increased risk of colitis associated colon cancer, depending on the duration, extent, and activity of the disease, and the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis, and this has led to considerable efforts to detect early lesions in UC.14–19 Furthermore, in contrast with sporadic CRC, lesions in UC patients do not follow the classical adenoma-carcinoma sequence but colitis associated dysplastic changes are first limited to the mucosa and submucosa and the growing pattern of dysplastic changes is often multifocal and flat. Thus chromoendoscopy in UC patients should be used in an extensive (panchromoendoscopy) rather than in a targeted fashion. In conjunction with magnifying endoscopes, chromoendoscopy in UC may offer the possibility of detecting dysplastic or neoplastic changes at a curable stage, and thus expand the indication for chromoendoscopy from screening to surveillance colonoscopy.

Rutter and colleagues13 investigated 100 patients with back to back colonoscopy, starting with random and targeted biopsies followed by panchromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies only. The design of this study is interesting although the potential value of chromoendoscopy after intensive random biopsies may even have been underestimated due to multiple bleedings that might have interfered with the chromoendoscopy procedure. But despite this potential limitation, the diagnostic yield of dysplastic changes was increased in this study by the use of chromoendoscopy from two to seven patients (3.5-fold increase) and from two to nine dysplastic lesions (4.5-fold increase). After panchromoendoscopy, a plethora of lesions were unmasked in UC patients. The majority of the lesions consisted of non-neoplastic tissue but this is a common problem using chromoendoscopy in a non-targeted fashion15 and endoscopists need to select and focus towards lesions with suspicious surface staining patterns.

New powerful endoscopes (high resolution and magnifying endoscopes) offer resolutions which allow new surface details to be seen on the colonic mucosa, such as the opening of the crypts. Kudo and colleagues16 were the first to note that some of the regular staining patterns were often seen in hyperplastic polyps or normal mucosa whereas unstructured surface architecture was associated with malignancy. This experience has led to categorisation of the different staining patterns in the colon. The so-called pit pattern classification16 differentiated five types and several subtypes. Types I and II are staining patterns that predict non-neoplastic lesions whereas types III to V predict neoplastic lesions (fig 1 ▶). With the help of this classification, the endoscopist can predict histology with good accuracy.

The study by Rutter et al demonstrates improved detection of colonic lesions in UC patients using chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine. This study strongly supports and extends recent studies in UC patients. In a randomised controlled trial using magnifying chromoendoscopy in patients with longstanding UC, we showed that the diagnostic yield for intraepithelial neoplasias was significantly increased by using methylene blue staining.18 More targeted biopsies were possible, and significantly more intraepithelial neoplasias were detected in the chromoendoscopy group. Using the modified pit pattern classification (pit patterns I–II: endoscopic prediction—non-neoplastic; pit patterns III–V: endoscopic prediction—neoplastic), both the sensitivity and specificity for differentiation between non-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions were 93%.18 Furthermore, Hurlstone19 recently analysed 162 patients with longstanding UC in a prospective study using magnifying chromoendoscopy with indigocarmine. After detection of subtle mucosal changes (such as fold convergence, air induced deformation, interruption of innominate grooves, or focal discrete colour change), targeted intravital staining with indigo carmine was used. Chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsy significantly increased the diagnostic yield for intraepithelial neoplasia and the number of flat neoplastic changes as opposed to conventional colonoscopy. Intraepithelial neoplasia in flat mucosal change was observed in 37 lesions, of which 31 were detected using chromoendoscopy. The overall sensitivity of magnifying chromoendoscopy in predicting neoplasia was 97% with a specificity of 93%.

In patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, inflammation is a frequent source of irritation for both the pathologist and the endoscopist. Thus anti-inflammatory therapy with proton pump inhibitors prior to chromo- and magnification endoscopy is recommended.17 We have obtained similar experience in patients with UC.18 Therefore, we believe that patients should undergo endoscopy in clinical remission as inflammatory activity in UC may mimic neoplastic changes. Based on these findings, pit pattern analysis should be limited to circumscript lesions only, whereas diffuse alterations should be attributed to local inflammation.18

One key question resulting from the above mentioned studies is whether there is still a need for random biopsies in unsuspicious mucosa after chromoendoscopy in UC patients. This is an important question as it takes a long time to perform 30–50 random biopsies during surveillance colonoscopy in UC. In our study, dysplastic tissue was seen only in conjunction with mucosal alterations (prior or after staining). Furthermore, Rutter et al found no dysplastic tissue in 2904 non-targeted biopsies.13,18 Taken together, these data suggest that targeted biopsies after intravital staining will replace random biopsies in the future, although prospective studies fully addressing this point are required. Although panchromoendoscopy requires additional time during surveillance colonoscopy (about 8–9 minutes),18 the use of targeted rather than random biopsies will save time. Therefore, the total time required for panchromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies is similar compared with colonoscopy with random biopsies but chromoendoscopy has a higher efficacy for detection of intraepithelial neoplasia, as shown by Rutter and colleagues.13

In summary, it appears that magnifying chromoendoscopy is an evolving new standard for surveillance colonoscopy in patients with longstanding UC. However, based on the currently available data,13,18,19 we would propose several guidelines (SURFACE) for the use of this new technique in patients with UC (see table 1 ▶). Furthermore, comparative studies will be required to determine the dye that should preferentially be used for chromoendoscopy (methylene blue v indigo carmine) in UC. The ability of the dye technique to differentiate neoplastic from non-neoplastic lesions and to enhance detection of dysplastic lesions in flat mucosa is a major advance in dysplasia surveillance in UC however. With the help of this new technique, the old problem of missing flat colonic lesions in patients with UC should be overcome and more patients with intraepithelial neoplasias will be diagnosed. However, magnifying chromoendoscopy cannot solve the problem of differentiating between colitis associated dysplasia and adenoma as the staining pattern of both entities is similar. However, chromoendoscopy significantly increases the diagnostic yield of intraepithelial neoplasias in UC compared with conventional colonoscopy by 3–4-fold. Differentiation of non-neoplastic from neoplastic lesions is possible by using surface staining analysis of circumscript lesions with a high overall sensitivity and specificity. It thus appears that the golden era of magnifying chromoendoscopy in UC is just about to begin.

Table 1.

Seven guidelines (SURFACE) for chromoendoscopy in ulcerative colitis

| (1) Strict patient selection. |

| Patients with histologically proven ulcerative colitis and at least eight years’ duration in clinical remission. Avoid patients with active disease. |

| (2) Unmask the mucosal surface. |

| Excellent bowel preparation is needed. Remove mucus and remaining fluid in the colon when necessary. |

| (3) Reduce peristaltic waves. |

| When drawing back the endoscope, a spasmolytic agent should be used (if necessary). |

| (4) Full length staining of the colon. |

| Perform full length staining of the colon (panchromoendoscopy) in ulcerative colitis rather than local staining |

| (5) Augmented detection with dyes. |

| Intravital staining with 0.4% indigo carmine or 0.1% methylene blue should be used to unmask flat lesions more frequently than with conventional colonoscopy. |

| (6) Crypt architecture analysis. |

| All lesions should be analysed according to the pit pattern classification. Whereas pit pattern types I–II suggest the presence of non-malignant lesions, staining patterns III–V suggest the presence of intraepithelial neoplasias and carcinomas. |

| (7) Endoscopic targeted biopsies. |

| Perform targeted biopsies of all mucosal alterations, particularly of circumscript lesions with staining patterns indicative of intraepithelial neoplasias and carcinomas (pit patterns III–V). |

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambert R, Provenzale D, Ectors N, et al. Early diagnosis and prevention of sporadic colorectal cancer. Endoscopy 2001;33:1042–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology 1997;112:24–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bensen S, Mott LA, Dain B, et al. The colonoscopic miss rate and true one-year recurrence of colorectal neoplastic polyps. Polyp Prevention Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haseman JH, Lemmel GT, Rahmani EY, et al. Failure of colonoscopy to detect colorectal cancer: evaluation of 47 cases in 20 hospitals. Gastrointest Endosc 1997;45:451–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorski TF, Rosen L, Riether R, et al. Colorectal cancer after surveillance colonoscopy: false-negative examination or fast growth? Dis Colon Rectum 1999;42:877–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ee HC, Semmens JB, Hoffman NE, et al. Complete colonoscopy rarely misses cancer. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:167–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo S, Kashida H, Tamura T, et al. Colonoscopic diagnosis and management of nonpolypoid early colorectal cancer. World J Surg 2000;24:1081–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajioka Y, Watanabe H, Kazama S, et al. Early colorectal cancer with special reference to the superficial nonpolypoid type from a histopathologic point of view. World J Surg 2000;24:1075–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii T, Rembacken BJ, Dixon MF, et al. Flat adenomas in the United Kingdom: are treatable cancers being missed? Endoscopy 1998;30:437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rembacken BJ, Fujii T, Cairns A, et al. Flat and depressed colonic neoplasms: a prospective study of 1000 colonoscopies in the UK. Lancet 2000;8:1211–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saitoh Y, Waxmann I, West AB, et al. Prevalence and distinctive biological features of flat colorectal adenomas in a North American population. Gastroenterology 2001;120:1657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fennerty MB. Should chromoscopy be part of the “proficient” endoscopist’s armamentarium? Gastrointest Endosc 1998;47:313–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Schofield G, et al. Pancolonic indigo carmine dye spraying for the detection of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2003;53:256–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messmann H, Endlicher E, Freunek G, et al. Fluorescence endoscopy for the detection of low and high grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis using systemic or local 5-aminolaevulinic acid sensitisation. Gut 2003;52:1003–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiesslich R, von Bergh M, Hahn M, et al. Chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine improves the detection of adenomatous and non-adenomatous lesions in the colon. Endoscopy 2001;33:1001–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T, et al. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiesslich R, Jung M. Magnification endoscopy: does it improve mucosal surface analysis for the diagnosis of gastrointestinal neoplasias? Endoscopy 2002;34:819–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, et al. Methylene blue aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2003;124:880–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurlstone DP. Further validation of high-magnification-chromoscopic-colonoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2003. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]