Abstract

Background: It is possible to manipulate the composition of the gastrointestinal microflora by administration of pre- and probiotics. This may help to preserve gut barrier function and reduce the incidence of septic morbidity.

Aims: To assess the effects of a combination of pre- and probiotics (synbiotic) on bacterial translocation, gastric colonisation, systemic inflammation, and septic morbidity in elective surgical patients.

Patients: Patients were enrolled two weeks prior to elective abdominal surgery. Seventy two patients were randomised to the synbiotic group and 65 to the placebo group. Patients were well matched regarding age and sex distribution, diagnoses, and POSSUM scores.

Methods: Patients in the synbiotic group received a two week preoperative course of Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12, Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus bulgaricus, together with the prebiotic oligofructose. Patients in the placebo group received placebo capsules and sucrose powder. At surgery, a nasogastric aspirate, mesenteric lymph node, and scrapings of the terminal ileum were harvested for microbiological analysis. Serum was collected preoperatively and on postoperative days 1 and 7 for measurement of C reactive protein, interleukin 6, and antiendotoxin antibodies. Septic morbidity and mortality were recorded.

Results: There were no significant differences between the synbiotic and control groups in bacterial translocation (12.1% v 10.7%; p = 0.808, χ2), gastric colonisation (41% v 44%; p = 0.719), systemic inflammation, or septic complications (32% v 31%; p = 0.882).

Conclusions: In this study, synbiotics had no measurable effect on gut barrier function in elective surgical patients. Further studies investigating the place of pre- and probiotics in clinical practice are required.

Keywords: prebiotics, probiotics, synbiotics, bacterial translocation

There is an increasing body of evidence to support the hypothesis that disruption of the gut barrier in humans can result in systemic inflammation and septic complications.1,2 Bacterial translocation is the term given to the process by which intraluminal bacteria transgress the intestinal mucosa to reach local lymph nodes. Both bacterial translocation and gastric colonisation with potentially pathogenic bacteria have been shown to be associated with an increased incidence of postoperative sepsis.3

It is possible to manipulate the composition of the gastrointestinal microflora by administration of pre- and probiotics, and so modulate this component of the gut barrier. Probiotics are live microbial supplements which have a beneficial effect on the host by altering gastrointestinal flora.4 Prebiotics are non-digestible sugars that selectively stimulate the growth of certain colonic bacteria.5 When administered in combination, prebiotics may enhance the survival of probiotic strains, as well as stimulating the activity of the host’s endogenous bacteria.6 The combination of a pre- and probiotic has been termed a synbiotic.7

Probiotic strains have been shown to inhibit bacterial adherence and translocation in animal and in vitro studies but the evidence is less clear in humans.8–10 In a recent study of 129 elective surgical patients, we found that administration of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 299V alone for nine days preoperatively did not influence the rate of bacterial translocation or the incidence of postoperative sepsis.11 The present study was conducted in order to investigate the effects of a combination of pre- and probiotic (synbiotic) on bacterial translocation, gastric colonisation, systemic inflammation, and postoperative sepsis in elective surgical patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A total of 144 patients listed for elective laparotomy were enrolled into the study two weeks prior to surgery. Patients who had received antibiotics in the month prior to surgery were excluded. Seven further patients were excluded; four procedures were cancelled, two patients had intraperitoneal pus at laparotomy, and one patient presented acutely and underwent emergency laparotomy

The remaining 137 patients were randomised into “synbiotic” (n = 72) and “placebo” (n = 65) groups. Treatment allocation was performed by the hospital pharmacist by means of a randomly generated sequence of sealed opaque envelopes. Patients in the two groups were well matched for age, sex distribution, diagnoses, and POSSUM scores (table 1 ▶). The majority of patients (68%) underwent colectomy and the overall incidence of malignancy was 62%. Forty two patients in the synbiotic group and 48 in the placebo group received bowel preparation in the form of sodium picosulphate (two sachets of Picolax; Nordic, Feltham, UK) the day prior to surgery. Acid suppression therapy was not used routinely.

Table 1.

Patient details

| Placebo group | Synbiotic group | |

| No of patients | 65 | 72 |

| Age (y) (median (IQR)) | 71 (66–80) | 71 (47–76) |

| Sex (M:F) | 42:23 | 38:34 |

| POSSUM score (median (IQR)) | 28 (25–32) | 30 (25–33) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Gastrointestinal malignancy | 43 | 43 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 7 | 10 |

| Diverticular disease | 7 | 6 |

| Aortic aneurysm | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 5 | 11 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Patients randomised into the synbiotic group received probiotics (Trevis; Christen Hansen, Denmark) in a dose of one capsule three times a day, and a prebiotic (16 g oligofructose powder dissolved in a cupful of water) twice daily for 1–2 weeks preoperatively. The control group received an identical quantity of placebo capsules (Christen Hansen) and sucrose powder. Postoperatively the trial medication was reintroduced as tolerated, and treatment continued until discharge from hospital. Each Trevis capsule contained 4×109 colony forming units of Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12, and Streptococcus thermophilus. Both patients and physicians were “blinded” as to whether active or placebo medication was given.

Assessment of gastric colonisation and bacterial translocation

We have previously described techniques for assessing gastric colonisation and bacterial translocation.3 All microbiological samples were obtained prior to administration of prophylactic antibiotics. A 5 ml nasogastric aspirate was obtained at the time of induction of anaesthesia and transported to the laboratory in a sealed sterile container for culture. Immediately after opening the peritoneum, a lymph node was excised from the ileocaecal mesentery, and a serosal scraping taken from the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum using a fresh surgical blade. Both samples were transported immediately in sterile saline to the laboratory for culture.

The lymph node and serosal samples were separately homogenised in sterile saline using a stomacher (Seward Medical, London, UK). The homogenates and nasogastric aspirates were inoculated onto blood agar and cystine-lactose-electrolyte deficient medium for aerobic incubation, and blood and neomycin containing medium for anaerobic incubation. All cultures were maintained at 37°C for 48 hours. Isolates grown from lymph nodes, serosal scrapings, and nasogastric aspirates were identified using standard microbiological techniques.12,13

Systemic inflammatory response and endotoxin exposure

In order to quantify the systemic inflammatory response and endotoxin exposure, serum was collected preoperatively and on postoperative days 1 and 7 for analysis of C reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and antiendotoxin core antibody (IgM EndoCAb). CRP levels were measured by routine autoanalysis (Synchron CX Systems, Beckman Coulter Inc, California, USA). Serum IL-6 was quantified using a commercially available ELISA (Quantikine, R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, USA), as was serum IgM EndoCAb (Eskia EndoCAB, Eskia Midlothian, UK).

POSSUM and septic morbidity

Physiological and operative severity scores for enumeration of morbidity (POSSUM) scores were calculated for each patient at the time of surgery.14 Septic complications were identified prospectively and defined as the presence of recognised pathogens in body tissues that are normally sterile, confirmed by the results of culture and supported by clinical, haematological, or radiological evidence. All patients received intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis in the form of cefuroxime 1.5 g and metronidazole 500 mg immediately after a mesenteric lymph node and serosal scraping had been harvested. Patients received a further two doses of cefuroxime and metronidazole in the first 24 hours postoperatively.

Statistical analysis

A sample size calculation based on the published prevalence of bacterial translocation demonstrated that approximately 44 patients would be required in each group to demonstrate a reduction in bacterial translocation from 15% to 0% at the 5% significance level with a power of 80%.3

Categorical data were compared using the χ2 test. Quantitative data were expressed as medians (interquartile range (IQR)) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for independent data and the Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired data. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 10.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

RESULTS

Synbiotic intake

Median preoperative intake of trial medication was 12 days in both groups. Five patients in the synbiotic group had problems relating to preoperative intake. Four patients had diarrhoea related to the oligofructose, and a further patient found it unpalatable. These patients continued with the Trevis capsules alone. There were no problems reported by patients in the placebo group. Median postoperative intake was four days in the synbiotic group and five days in the control group (p = 0.312, Mann-Whitney U).

Gastric colonisation

Nasogastric aspirates were obtained at the time of surgery from 121 patients (table 2 ▶). At least one organism was identified in 51 (42%) aspirates. The most common organism identified was Candida, comprising 53% of isolates. Seventeen (23%) isolates could be considered potentially pathogenic enteric derived organisms.

Table 2.

Organisms isolated from nasogastric aspirates

| Organism | Placebo group | Synbiotic group | |

| NGA obtained | 57 | 64 | |

| NGA positive | 25 (44%) | 26 (41%) | |

| NGA isolates | |||

| Enteric | Enterococcus | 2 | 1 |

| “Coliforms” (unspecified) | 0 | 1 | |

| Escherichia coli | 4 | 2 | |

| Proteae | 1 | 0 | |

| Klebsiella | 2 | 3 | |

| Citrobacter | 0 | 1 | |

| Non-enteric | Staphylococcus aureus | 3 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 2 | 3 | |

| Pseudomonas | 1 | 0 | |

| Diptheroids | 2 | 1 | |

| Candida | 17 | 22 | |

| Bacillus | 1 | 0 | |

| Group B strep | 1 | 0 | |

| Leuconostoc | 1 | 0 | |

| Lactobacillus | 1 | 0 | |

| Alpha-haemolytic staphylococci | 0 | 1 | |

| Micrococcus | 0 | 1 | |

| Total isolates | 38 | 36 | |

| Total enteric | 9 | 8 | |

NGA, nasogastric aspirates.

There was no difference in gastric colonisation between the placebo and synbiotic groups, with 25/57 (44%) positive aspirates in the placebo group and 26/64 (41%) in the synbiotic group (p = 0.719, χ2). There was no difference in the proportion of enteric organisms identified in each of the two groups (table 2 ▶).

The presence of multiple or enteric organisms in gastric juice was strongly associated with bacterial translocation to lymph nodes. Twenty nine per cent of patients with multiple organisms developed bacterial translocation to lymph nodes compared with 2% of patients with sterile or single organism isolates (p<0.001, χ2). Thirty one per cent of patients with enteric organisms developed bacterial translocation compared with 4% of patients with no enteric organisms (p<0.001, χ2).

Gastric colonisation was associated with an increase in the incidence of septic complications but this did not reach statistical significance. Patients with a positive nasogastric aspirate had a subsequent sepsis rate of 35% compared with a sepsis rate of 26% in patients with a sterile aspirate (p = 0.255, χ2).

Bacterial translocation

Details of the organisms isolated from mesenteric lymph nodes and terminal ileal serosal scrapings are shown in table 3 ▶. A lymph node was harvested in 122 patients (56 “placebo” and 66 “synbiotic”). A serosal sample was harvested in 115 of these patients. The overall incidence of translocation to nodes or serosa was 11.5% (14/122 patients). Eight of 122 (6.5%) lymph nodes and 8/115 (7.0%) serosal samples were positive for bacteria. A total of 20 bacterial isolates from 14 patients were identified, of which 12 (60%) were potentially pathogenic “enteric” organisms. Of the 14 patients who translocated, four grew an identical organism in their nasogastric aspirate, in two cases this was Staphylococcus epidermidis, in one case E coli, and in another Klebsiella.

Table 3.

Organisms isolated from mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and serosa

| Placebo group | Synbiotic group | |

| MLN obtained | 56 | 66 |

| MLN positive | 5 (9%) | 3 (5%) |

| Organisms cultured | ||

| Klebsiella | 3 | 1 |

| Escherichia coli | 2 | 1 |

| Enterococcus | 1 | 1 |

| Staph epidermidis | 2 | 1 |

| Serosa obtained | 53 | 62 |

| Serosa positive | 3 (6%) | 5 (8%) |

| Organisms cultured | ||

| Klebsiella | 1 | 0 |

| Escherichia coli | 1 | 0 |

| Enterococcus | 0 | 1 |

| Staph epidermidis | 1 | 4 |

| Total isolates | 11 | 9 |

| Total enteric isolates | 8 | 4 |

In two patients in the placebo group the same bacteria was isolated from both lymph node and serosa, and the organisms responsible were Klebsiella and E coli.

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of bacterial translocation (defined as a positive mesenteric lymph node or serosal scraping) between the placebo and synbiotic groups (6/56 (10.7%) v 8/66 (12.1%); p = 0.808, χ2). There was a difference in the proportion of enteric bacteria isolated, although this was not statistically significant. In the placebo group, 130 samples were analysed for evidence of translocation. Of these, six (4.6%) samples grew enteric bacteria. In the synbiotic group only 3/144 (2.0%) samples grew enteric bacteria (p = 0.240, χ2).

The incidence of postoperative sepsis in patients with evidence of translocation was 43% compared with 30% in patients with no evidence of translocation (p = 0.244, χ2).

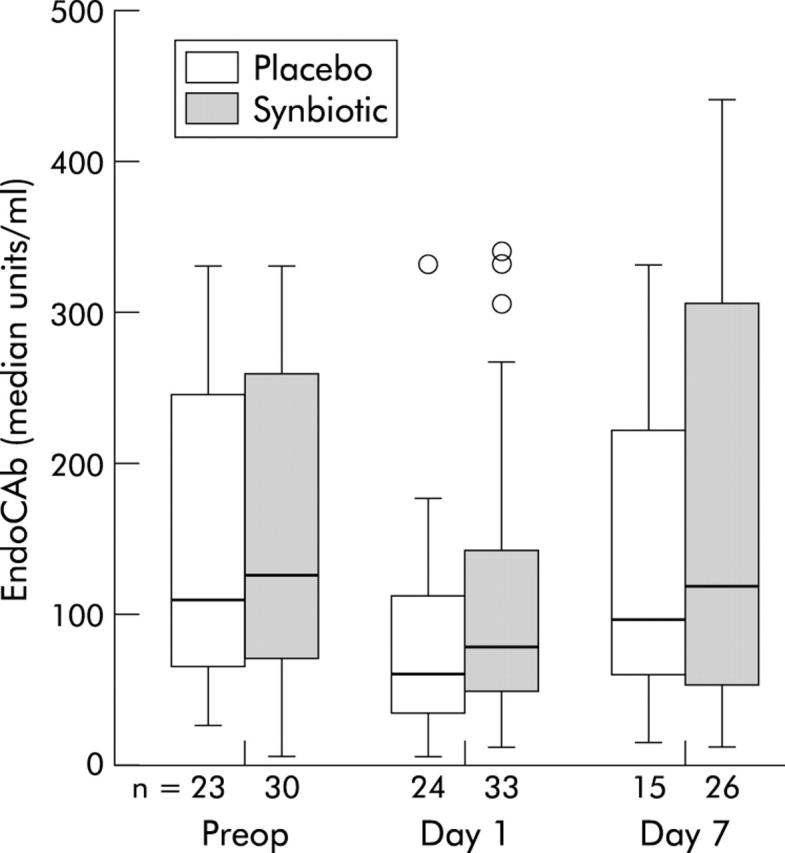

Systemic inflammatory response and endotoxin exposure

Serial CRP and IgM EndoCAb levels are shown in figs 1 ▶ and 2 ▶. IL-6 levels essentially mirrored CRP; median (IQR) levels in the placebo and synbiotic groups were, respectively, 9.72 (4.23–12.19) pg/ml and 7.21 (5.45–19.3) pg/ml preoperatively, 130.8 (98.1–177.8) pg/ml and 106.9 (59.6–182.9) pg/ml on the first postoperative day, and 16.5 (5.40–29.8) pg/ml and 15.2 (7.45–40.7) pg/ml on day 7. Both the placebo and synbiotic groups demonstrated a significant increase in CRP and IL-6 on the first postoperative day (p<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank). By day 7, IL-6 levels had fallen to preoperative values whereas CRP levels remained elevated. There were no significant differences between groups at any time point (p>0.05, Mann-Whitney U). Within each group, there were no significant differences between translocators and non-translocators (p>0.05 at each time point, Mann-Whitney U).

Figure 1.

Serial C reactive protein (CRP) levels in the synbiotic and placebo groups. There was a significant postoperative rise in CRP in both groups (p<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank) but no difference between the groups at any time point (p>0.05, Mann-Whitney U). Open circles, outliers (data points 1.5–3 box lengths from nearest quartile); *, extremes (data points >3 box lengths from nearest quartile).

Figure 2.

Serial antiendotoxin core antibody (EndoCAb) levels in the synbiotic and placebo groups. There was a significant postoperative fall in EndoCAb in both groups (p<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank) but no difference between the groups at any time point (p>0.05, Mann-Whitney U).

IgM EndoCAb levels fell significantly on the first postoperative day in both groups (p<0.05, Wilcoxon signed rank). Antibody levels had returned to baseline by day 7. There were no significant differences between the placebo and synbiotic groups at any time point (p>0.05, Mann-Whitney U). Within each group there were no significant differences between translocators and non-translocators (p>0.05 at each time point).

Septic morbidity, mortality, and duration of stay

There was no difference in the incidence of septic morbidity between the placebo and synbiotic groups (20/65 (31%) v 23/72 (32%); p = 0.882, χ2). The commonest sites of infection were the urinary tract (32%), respiratory tract (24%), and surgical wound (22%). Seventy three per cent of isolates obtained from septic foci were potentially pathogenic “enteric” bacteria. Fourteen patients (10%) died within 30 days of surgery, of which five were in the placebo group and nine in the synbiotic group (p = 0.354, χ2). Median duration of stay was eight days in both groups.

DISCUSSION

This prospective randomised controlled trial showed no evidence of benefit from a preoperative course of pre- and probiotics (synbiotics) in patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery. Synbiotics failed to impact significantly on gastric colonisation, bacterial translocation, the systemic inflammatory response, or septic morbidity. These results mirror those seen in a similar study in the authors’ institution employing the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 299V.11

There are many possible explanations to account for the failure in this study to show benefit from synbiotic administration. It could be argued that the wrong strains of probiotic organisms were used, that they were non-viable, that the dose was too low, or that patients were non-compliant. The authors consider all of these possibilities unlikely. Viability of the organisms administered was regularly confirmed by culture of the probiotic capsules. Little work has been performed on the optimal dose of probiotics but the concentration of organisms administered (3×109 per day of each species) was similar to that used in previous studies showing clinical benefit from probiotics.15–17 Patients were asked to bring their study medication to hospital when they were admitted for surgery, and the remaining capsules were counted in order to ensure that the prescribed amount had been consumed. We accept that the median duration of postoperative therapy was relatively short (four days in the placebo group and five in the synbiotic group); this reflects patient intolerance of the synbiotic preparation in the first 1–3 days following major abdominal surgery.

The pre- and probiotics used in this study were chosen on the basis of evidence from clinical and in vitro studies. Oligofructose is an inulin derivative which resists degradation in the upper gastrointestinal tract.18 Administration to healthy volunteers results in increased numbers of faecal bifidobacteria and a reduction in anaerobes and clostridia.19,20 The organisms present in Trevis capsules have been shown to survive transit of the upper gastrointestinal tract.21 Oral administration results in a detectable increase in the numbers of faecal Bifidobacterium and lactobacilli.22,23 The combination of administering oligofructose with multiple probiotic strains was designed to maximise the chance of detecting any treatment effect. While it might have been desirable to demonstrate the presence of viable probiotic organisms in faecal samples, the complex identification techniques required were outwith the scope of the current study.

We consider it unlikely that a beneficial effect of synbiotics on upper gastrointestinal microflora has been overlooked due to inappropriate patient selection. The rationale for the use of pre- and probiotics is that they alter gastrointestinal microflora to the benefit of the patient. In order to demonstrate such benefit, patients must therefore be colonised with potentially pathogenic organisms in the first place. The results of the current study confirm this; at least one organism was isolated from over 40% of gastric aspirates, and approximately 20% of isolates were potentially pathogenic “enteric” bacteria such as those seen in the majority of subsequent septic complications.

The results of this study regarding bacterial translocation are at variance with results from animal studies, many of which show a marked reduction in translocation following administration of probiotic strains.24–26 While the prevention of bacterial adhesion and translocation appears to be important in animal models, synbiotics might act via an alternative mechanism in humans, such as immunomodulation. Probiotic organisms have been shown to result in an increase in intestinal antibody and cytokine production and activation of T helper lymphocytes.4,27–29 Similar effects can also be seen at distant mucosal sites and in peripheral blood, implying activation of the mucosa associated immune system.30,31 It may be that immunomodulation, rather than a reduction in translocation, was responsible for the clinical benefit seen in recent clinical studies using probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus plantarum 299V.15,17,32

In the current study, no immunomodulatory effect was demonstrated using CRP and IL-6 as markers of systemic inflammation. It is possible that the magnitude of the surgical insult prevented detection of a subtle immunomodulatory effect. It is conceivable that such modulation of the immune response might become detectable following weeks or even months of postoperative synbiotics, as opposed to the short course administered in this study.

One other possible reason for failure to demonstrate benefit from synbiotics may have been insufficient sample size. The overall prevalence of bacterial translocation to lymph nodes was 6.6%, which is considerably lower than the predicted 15% used in the initial sample size calculation. A greater number of patients would be required in order to minimise the chance of a type 2 error with such low rates of translocation.

CONCLUSION

This prospective randomised controlled trial showed no evidence of benefit from a preoperative course of pre- and probiotics (synbiotics) in patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery. The particular synbiotic preparation used failed to impact significantly on gastric colonisation, bacterial translocation, the systemic inflammatory response, or septic morbidity. Generalisation of these results may not be warranted, and further studies investigating the place of pre- and probiotics in clinical practice are required.

Abbreviations

CRP, C reactive protein

IL-6, interleukin 6

IgM EndoCAb, antiendotoxin core antibody

POSSUM score, physiological and operative severity scores for enumeration of morbidity

IQR, interquartile range

REFERENCES

- 1.Marshall JC, Christou NV, Meakins JL. The gastrointestinal tract. The “undrained abscess” of multiple organ failure. Ann Surg 1993;218:111–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacFie J. Bacterial translocation in surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1997;79:183–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacFie J, O’Boyle C, Mitchell CJ, et al. Gut origin of sepsis: a prospective study investigating associations between bacterial translocation, gastric microflora, and septic morbidity. Gut 1999;45:223–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Probiotics, infection and immunity. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2002;15:501–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bengmark S. Pre-, pro- and synbiotics. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2001;4:571–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleeson B, Sykura B, Zunft HJ, et al. Effects of inulin and lactose on fecal microflora, microbial activiy, and bowel habit in elderly constipated persons. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:1397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberfroid M. Prebiotics and synbiotics: concepts and nutritional properties. Br J Nutr 1998;80 (suppl 2) :S197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernet MF, Brassart D, Neeser JR, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus LA 1 binds to cultured human intestinal cell lines and inhibits cell attatchment and cell invasion by enterovirulent bacteria. Gut 1994;35:483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxelin M. Lactobacillus GG—A human probiotic strain with thorough clinical documentation. Food Rev Int 1997;13:293–313. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forestier C, De Champs C, Vatoux C, et al. Probiotic activities of Lactobacillus casei rhamnosus: in vitro adherence to intestinal cells and antimicrobial properties. Res Microbiol 2001;152:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNaught CE, Woodcock NP, MacFie J, et al. A prospective randomised study of the probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 299V on indices of gut barrier function in elective surgical patients. Gut 2002;51:827–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrow GI, Feltham RK. Cowan and Steel’s manual for identification of medical bacteria, 3rd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- 13.Stokes J, Ridgeway GL. Clinical bacteriology, 5th edn. Sevenoaks, UK: Edward Arnold, 1980.

- 14.Neary D, Heather BP, Earnshaw JJ. The Physiological and Operative Severity Score for the enUmeration of Mortality and morbidity (POSSUM). Br J Surg 2003;90:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rayes N, Seehofer D, Hansen S, et al. Early enteral supply of lactobacillus and fiber versus selective bowel decontamination: a controlled trial in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation 2002;74:123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill HS, Rutherfurd KJ, Cross ML, et al. Enhancement of immunity in the elderly by dietary supplementation with the probiotic Bifidobacterium lactis HN019. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;74:833–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olah A, Belagyi T, Issekutz A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of specific lactobacillus and fibre supplementation to early enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2002;89:1103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellegard L, Andersson H, Bosaeus I. Inulin and oligofructose do not influence the absorption of cholesterol, or the excretion of cholesterol, Ca, Mg, Zn, Fe, or bile acids but increases energy excretion in ileostomy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 1997;51:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gibson GR. Dietary modulation of the human gut microflora using the prebiotics oligofructose and inulin. J Nutr 1999;129 (suppl 7) :1438–41S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menne E, Guggenbuhl N, Roberfroid M. Fn-type chicory inulin hydrolysate has a prebiotic effect in humans. J Nutr 2000;130:1197–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hove H, Nordgaard-Andersen I, Mortensen PB. Effect of lactic acid bacteria on the intestinal production of lactate and short-chain fatty acids, and the absorption of lactose. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link-Amster H, Roxhat F, Saudan KY, et al. Modulation of a specific humoral immune response and changes in intestinal flora mediated through fermented milk intake. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1994;10:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiffrin EJ, Brassart D, Servin AL, et al. Immune modulation of blood leukocytes in humans by lactic acid bacteria: criteria for strain selection. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:515–20S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shu Q, Gill HS. Immune protection mediated by the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20) against Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection in mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2002;34:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eizaguirre I, Urkia NG, Asensio AB, et al. Probiotic supplementation reduces the risk of bacterial translocation in experimental short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 2002;37:699–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill HS, Shu Q, Lin H, et al. Protection against translocating Salmonella typhimurium infection in mice by feeding the immuno-enhancing probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain HN001. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl) 2001;190:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perdigon G, Maldonado Galdeano C, Valdez JC, et al. Interaction of lactic acid bacteria with the gut immune system. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002;56 (suppl 4) :S21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perdigon G, Vintini E, Alvarez S, et al. Study of the possible mechanisms involved in the mucosal immune system activation by lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci 1999;82:1108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tejada-Simon MV, Ustunol Z, Pestka JJ. Ex vivo effects of lactobacilli, streptococci, and bifidobacteria ingestion on cytokine and nitric oxide production in a murine model. J Food Prot 1999;62:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perdigon G, Fuller R, Raya R. Lactic acid bacteria and their effect on the immune system. Curr Issues Intest Microbiol 2001;2:27–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gill HS, Cross ML, Rutherfurd KJ, et al. Dietary probiotic supplementation to enhance cellular immunity in the elderly. Br J Biomed Sci 2001;58:94–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayes N, Seehofer D, Muller AR, et al. Influence of probiotics and fibre on the incidence of bacterial infections following major abdominal surgery—results of a prospective trial. Z Gastroenterol 2002;40:869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]