Abstract

Background and aim: The colonic microflora is involved in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease (CD) but less than 30% of the microflora can be cultured. We investigated potential differences in the faecal microflora between patients with colonic CD in remission (n=9), patients with active colonic CD (n=8), and healthy volunteers (n=16) using culture independent techniques.

Methods: Quantitative dot blot hybridisation with six radiolabelled 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) targeting oligonucleotide probes was used to measure the proportions of rRNA corresponding to each phylogenetic group. Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE) of 16S rDNA was used to evaluate dominant species diversity.

Results: Enterobacteria were significantly increased in active and quiescent CD. Probe additivity was significantly lower in patients (65 (11)% and 69 (6)% in active CD and quiescent CD) than in healthy controls (99 (7)%). TTGE profiles varied markedly between active and quiescent CD but were stable in healthy conditions.

Conclusion: The biodiversity of the microflora remains high in patients with CD. Enterobacteria were observed significantly more frequently in CD than in health, and more than 30% of the dominant flora belonged to yet undefined phylogenetic groups.

Keywords: faecal microflora, Crohn's disease, temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis

Some members of the endogenous faecal microflora have a clear detrimental role in most animal models of colitis and enteritis. This is also strongly suspected to be the case in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), especially Crohn's disease (CD).1,2 In particular, diversion of the faecal stream prevents postoperative recurrence of ileal CD.3 Likewise, Harper et al reported that reintroduction of small bowel effluent into the colon of patients with Crohn's colitis treated by split ileostomy induced inflammation while reintroduction of a sterile ultrafiltrate of the small bowel effluent did not.4 Not all bacteria have the same proinflammatory properties, and some may even be protective.5,6 Indeed, several studies have recently suggested that probiotic microorganisms such as lactobacilli, bifidobacteria, and Saccharomyces may favourably influence the course of CD.7–9 Previous studies of the colonic microflora in CD have been hampered by several factors. All have used bacterial culture techniques but less than 30% of the total microflora can be cultured.10 Moreover, factors that may influence the composition of the microflora, such as disease location and activity, antibiotic exposure, bowel cleansing, and artificial nutrition, have not been taken into account.

Molecular analysis of the bacterial microflora based on the 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) genes obviates the need for culture and can be used to characterise approximately 90% of the dominant faecal microflora in healthy subjects.10–14 The relative proportions of the dominant phylogenetic groups of bacteria present in faecal samples can be assessed by quantitative dot blot analysis, and biodiversity can be estimated using temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE).15,16 The aim of this study was to investigate the population structure (that is, proportions of predominant phylogenetic groups) of the faecal microflora of patients with colonic CD in comparison with healthy volunteers, and to compare the biodiversity of the faecal flora between CD patients with active disease and those in disease remission.

PATIENTS

Seventeen patients with colonic or ileocolonic CD were studied. Faecal samples were collected from 13 patients in remission (CD activity index (CDAI) <150)17 and from eight patients with active CD (CDAI >150, mean 260). Four patients provided faecal samples during both remission and active disease. None of the patients had taken antibiotics, sulphasalazine, or undergone colon cleansing for at least four weeks. Their characteristics are given in table 1 ▶. Faecal samples were also obtained from 16 healthy volunteers (aged 40 (3) years; seven males/nine females) who had not taken antibiotics for at least four weeks. The stability of the dominant flora, as assessed by the TTGE profile, was studied in one healthy subject who provided five faecal samples over a two year period.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with Crohn's disease (CD)

| Inactive CD* | Active CD* | Paired samples† | |

| n | 9 | 8 | 4 |

| Mean age (y) | 47 (32–62) | 35 (16–68) | 35 (16–69) |

| Sex ratio (M/F) | 3/6 | 1/7 | 1/3 |

| Localisation | |||

| Ileum | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Right colon | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Left colon | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Rectum | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Anus-perineum | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Ileocaecal or limited colon resection | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Corticosteroids | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Purine analogues | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Mesalazine | 5 | 3 | 3 |

*Patients who were studied only during inactive or active disease.

†Characteristics during inactive CD for patients who were studied both in remission and during active disease.

METHODS

Within one hour of emission by hospitalised patients, faecal samples were aliquoted in Starstedt 2.2 ml screw cap tubes and frozen at −80°C. They were stored at −80°C until analysis.

Dot blot hybridisation

Stools were analysed by quantitative dot blot hybridisation as formerly described by Doré and colleagues.10 Total RNA was extracted from frozen faecal material and from reference microbial strains. RNA extracts dotted on membranes were hybridised with a panel of 16S rRNA targeted oligonucleotide probes to assess six independent bacterial phylogenetic groups representing approximately 90% of the healthy adult faecal bacterial rRNA (table 2 ▶). The Bacteroides group includes all species of the genera Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas11; Bifidobacterium is the whole genus comprising all Bifidobacterium species; Lactobacillus includes all species of Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Lactococcus, Pediococcus, and Leuconostoc21; the Clostridium leptum and Clostridium coccoides groups both include species of the genera Eubacterium, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium as well as several particular species such as Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, Coprococcus eutactus, and Fusobacterium prausnitzii19–20; finally, the Enterobacteria group comprises the entire enterobacteriaceae family. The abundance of each group was expressed as rRNA index—that is, specific 16S rRNA as a proportion of total bacterial 16S rRNA (means (SEM) of triplicate measurements). Reference strains used as standards to evaluate rRNA indexes were Bacteroides vulgatus ATCC 8482, Bifidobacterium longum ATCC 15707, Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356, Eubacterium siraeum ATCC 29066, Ruminococcus productus ATCC 27340, and Escherichia coli (rRNA standard; Roche, Meylan, France).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide probes used in this study

| Phylogenetic group* | Probe | Sequence (5`-3`) | Name† | Reference |

| Universal | Univ1390 | - GACGGGCGGTGTGTACAA - | S-*-Univ-1390-a-A-18 | Zheng13 |

| Bacteria | Eub338 | - GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT - | S-D-Bact-0338-a-A-18 | Amann18 |

| Clostridium coccoides | Erec482 | - GCTTCTTAGTCA(A/G)GTACCG - | S-*-Erec-0482-a-A-19 | Franks19 |

| Clostridium leptum | Clept1240 | - GTTTT(A/G)TCAACGGCAGTC - | S-G-Clept-1240-a-A-18 | Sghir20 |

| Bacteroides-Porphyromonas-Prevotella | Bacto1080 | - GCACTTAAGCCGACACCT - | S-*-Bacto-1080-a-A-18 | Doré11 |

| Bifidobacterium | Bif228 | - GATAGGACGCGACCCCAT - | S-G-Bif-228-a-A-18 | Mangin21 |

| Enterobacteria | Enter1418 | - CTTTTGCAACCCACT - | S-G-Enter-1418-a-A-15 | Chmieliewski et al, submitted |

| Lactobacillus-Streptococcus-Enterococcus | Lacto722 | - YCACCGCTACACATGRAGTTCCACT - | S-G-Lacto-0722-a-A-25 | Sghir22 |

*Name of the phylogenetic group used in this study.

†Probe names in accordance with the Oligonucleotide Probe Database.

Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE)

DNA isolation and rDNA amplification

Total DNA was extracted as previously described16 from 0.2 g faecal samples. The concentration and integrity of the nucleic acids were determined visually by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide.

Primers GCclamp-U968 (5` GCclamp- GAA CGC GAA GAA CCT TAC) and L1401 (5` GCG TGT GTA CAA GAC CC) were used to amplify the V6 to V8 regions of bacterial 16S rDNA.15 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using Hot Star Taq DNA polymerase (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). The PCR mix (50 μl) contained 1×PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM each dNTP, 20 pmol of primers U968-GC and L1401, 2.5 U of Hot Star Taq polymerase, and approximately 2 ng of DNA. Samples were amplified in a PCT 100 thermocycler (MJ Research, Inc, USA) using the following programme: 95°C for 15 minutes, 30 cycles of 97°C for one minute, 58°C for one minute, 72°C for one minute 30 seconds, and finally 72°C for 15 minutes.16 PCR products were analysed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide to check their size (500 bp) and estimate their concentration.

TTGE analysis of PCR amplicons

We used the DCode Universal Mutation Detection System (Bio-Rad, Paris, France) for sequence specific separation of PCR products. Electrophoresis was performed through a 1 mm thick, 16×16 cm polyacrylamide gel (8% wt/vol acrylamide/Bis, 7 M urea, 1.25× TAE, and, respectively, 55 μl and 550 μl of temed and 10% ammonium persulfate) using 7 litres of 1.25× TAE as the electrophoresis buffer. Electrophoresis was run at a fixed voltage of 64 V for 16 hours with an initial temperature of 66°C and a ramp rate of 0.2°C/h. For better resolution, voltage was fixed at 20 V for 15 minutes at the beginning of electrophoresis. Each well was loaded with 100–200 ng of amplified DNA plus an equal volume of 2× gel loading dye (0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol, and 70% glycerol). A marker obtained by M Sutren was used for each gel. It consists of a PCR amplification mix of cloned rDNA from C coccoides (Nos 157, 93, and 40), C leptum (Nos 365 and 296), and Bacteroides (Nos 303 and 73).23 Gels were stained in the dark by immersion for 30 minutes in a solution of SYBR Green I Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and read on the Storm system (Molecular Dynamics).

Calculations and statistical analysis

Dot blot hybridisation experiments were done in triplicate and the results expressed as means (SEM) of the rRNA index (percentage of total bacterial 16S rRNA). Additivity of the probes represents the added contribution of all six probes to total bacterial rRNA. TTGE profiles were analysed using GelCompar software (version 2.0 Applied Maths, Kortrigk, Belgium; licence AJC7-8JHL-AX57-ANEV-GFEJ-AV47). Analysis included calculation of the number of bands for each pattern, and between pattern comparisons using the Pearson coefficient calculated as a measure of the degree of similarity. Statistical comparisons were made among groups of subjects (that is, healthy subjects, patients with CD in remission, and patients with active CD). Comparisons were made using the Student's t test for variables with a normal distribution, and otherwise using Wilcoxon's test.

RESULTS

Composition of the faecal microflora as assessed by dot blot hybridisation

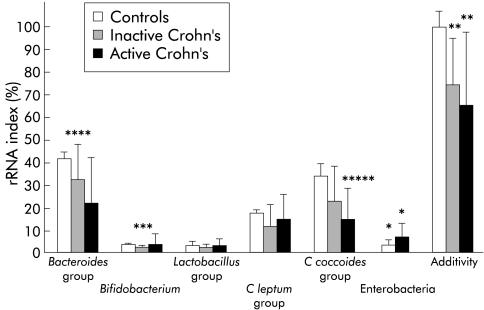

Significant hybridisation signals were detected for Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, C leptum, and C coccoides groups, indicating their presence in the dominant microflora of all faecal samples analysed. The relative proportions of the bacterial populations in the three groups of subjects are shown in fig 1 ▶. A signal for enterobacteria was detected in all samples from patients with CD but in none of the samples from healthy subjects. Enterobacterial rRNAs were not significantly different in patients with active disease compared with those in remission (p=0.193). Both Bacteroides group and bifidobacteria tended to be less represented in the bacterial rRNA of CD patients. Compared with healthy controls, these differences were significant only for patients with inactive disease (p=0.013 for Bacteroides groups and p=0.010 for bifidobacteria). Additivity of the probes was significantly lower for samples from CD patients (active or inactive disease) than from healthy subjects (p=0.006, fig 1 ▶) indicating that an average 30% of the bacterial rRNA in the patients' dominant flora was not accounted for by the six probes.

Figure 1.

Composition of the dominant faecal flora, as assessed by dot blot hybridisation with specific probes in healthy volunteers, patients with inactive Crohn's disease, and independent patients with active Crohn's disease. Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) indexes correspond to specific 16S rRNA as a proportion of total bacterial 16S rRNA (means (SEM) of triplicate measurements). Comparison versus healthy subjects : *p=0.0001, **p=0.006, ***p=0.010, ****p=0.013, *****p=0.034.

The following results were obtained in four patients who were studied during both active and inactive disease phases (mean (SEM) rRNA%, active and inactive disease, respectively): Bacteroides 7.2 (2.7) and 29.2 (10.3), Bifidobacterium spp 5.5 (2.8) and 5.0 (2.1), Lactobacillus 3.3 (0.8) and 2.5 (1.0), C leptum 19.4 (4.0) and 26.4 (10.8), C coccoides 10.9 (5.0) and 21.7 (6.3), and Enterobacteria 4.5 (2.3) and 3.7 (0.4).

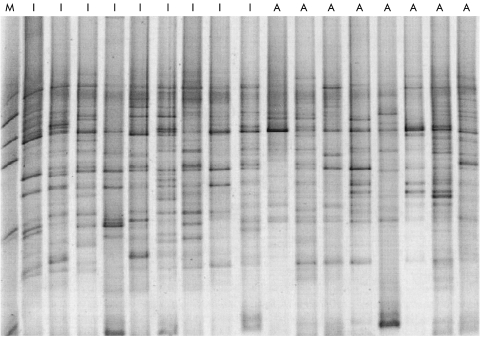

Biodiversity of the faecal flora as assessed by TTGE

The TTGE profiles of the independent patients in remission (n=9) and of those with active CD (n=8) are shown in fig 2 ▶. They varied greatly between subjects, and the banding pattern was complex in all cases. The number of bands was 19.9 (2.5) during remission and 16.5 (4.9) during active disease (p=0.086).

Figure 2.

Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA amplicons (obtained using primers for the V6-V8 region of the gene) of samples obtained from independent patients during active and inactive colonic Crohn's disease. M, Marker, composed of a polymerase chain reaction amplification mix of cloned rDNA from Clostridium coccoides (Nos 157, 93, and 40), Clostridium leptum (Nos 365 and 296), and Bacteroides (Nos 303 and 73)23. I, inactive disease; A, active disease.

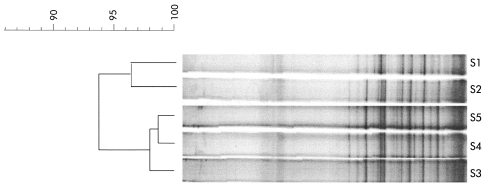

The Pearson coefficients for comparisons between the banding patterns obtained in the healthy subject who provided five samples over two years ranged between 93% and 98% for day to day comparisons (four faecal samples collected over 80 days) and over 93% for comparisons among samples collected over two years (fig 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA amplicons of the dominant flora in a healthy control subject sampled over a two year period. S1, sample collected in 1997; S2–S5, samples collected in 1999 on days 1, 23, 58, and 78, respectively. The dendrogram gives a statistically optimal representation of similarities between temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis profiles based on the matrix of Pearson correlation coefficients and applying the Unweighted Pair Group Method using Arithmetic averages (UPGMA).

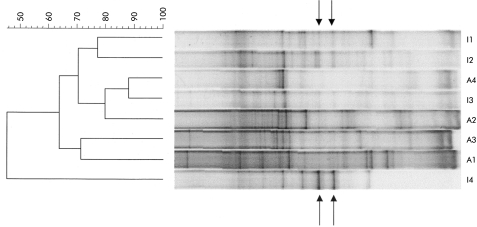

TTGE profiles for the four patients who were studied during both active and inactive disease phases are shown in fig 4 ▶. The banding patterns for each patient varied markedly between the two phases. Pearson coefficients for comparisons between banding patterns during remission versus active disease were below 50% for one patient and approximately 70% for the others (fig 4 ▶). There was a mean loss of 1.7 (2.7) bands during active disease (p=0.29). Some bands were observed only during active disease but none was present in all patients. Two bands were observed only during remission in all four patients, as shown in fig 4 ▶.

Figure 4.

Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S rDNA amplicons of paired faecal samples from four patients who were studied during both active and inactive Crohn's disease. The dendrogram was obtained as indicated in fig 3 ▶. IX, sample from patient X during inactive disease; AX, sample from patient X during active disease.

DISCUSSION

Using a molecular approach, we observed that the faecal microflora in patients with both inactive and active colonic CD differed from the faecal microflora of healthy subjects, containing significantly more enterobacteria. In addition, approximately 30% of the dominant bacteria did not belong to the usual dominant phylogenetic groups. During active disease, the equilibrium of the dominant microflora was disturbed but species diversity remained high.

Several lines of evidence point to a role of the endogenous microflora in the pathogenesis of CD. Intestinal lesions predominate in the distal parts of the gastrointestinal tract where the intestinal microflora is most abundant, and bacteria present in the faecal stream have been reported to be responsible for the recurrence of intestinal lesions after surgery.3,4,24,25 Less than 30% of the endogenous colonic bacteria can be cultured.10,23 Modern molecular techniques based on nucleic acid sequence comparisons are powerful tools for culture independent characterisation of the microbial composition of complex ecosystems,26 and give a better representation of the dominant bacterial populations. The methods used in the present study allowed the detection of a phylogenetic group (dot blot) or a bacterial species (individual 16S rRNA sequence in TTGE) only if it represents at least 1% of the total bacterial microflora27—that is, approximately 108 bacteria per gram. Such methods cannot detect bacteria of low concentration, some of which may be identified by culture techniques.

To examine primary alterations of the endogenous microbiota during remission, we selected CD patients with colonic disease who had not received antibiotics, sulphasalazine, or colonic cleansing for at least four weeks before analysis. Our patients received treatments required for the maintenance of remission—that is, mesalazine, corticosteroids, or immunosuppressors. The effects of such treatments on the composition of the microflora are unknown. We decided not to study patients treated with sulphasalazine as it may influence the microflora, probably because of the sulphonamide moiety.28

The increase in enterobacteria during both inactive and active CD has already been suggested in culture based studies.29,30 Escherichia coli strains have been implicated in the pathogenesis of CD, especially some strains with particular adhesion properties which are increased in ileal lesions of CD.31 In contrast, however, E coli strain Nissle 1917 may have a protective effect when administered orally, as suggested by clinical trials in patients with ulcerative colitis32–34 and CD.7

Bacteroides exhibited proinflammatory properties in several animal models of IBD.35 While some culture studies have suggested a possible increase in faecal Bacteroides in CD,36,37 we observed a decrease in the relative proportions of the Bacteroides phylogenetic group. The group probe hybridises with Bacteroides but also members of the Porphyromonas and Prevotella genera, and cannot detect subtle specific modifications of Bacteroides at the species level, for example B vulgatus.37 Bifidobacteria and lactobacilli (or at least some members of these groups) are considered by some authors to be potentially protective against IBD.5,38–40 This is essentially based on studies with probiotic strains which appear to protect against inflammation in animal models of IBD5,38,39 and in recent clinical trials.9,40,41 One previous study suggested that bifidobacteria counts were decreased during CD,42 and we noted a trend towards such a decrease in our patients, the decrease being significant only in patient with inactive disease. The putative protective role of bifidobacteria against CD remains to be confirmed, but Campieri et al reported that the probiotic VSL#3 which contains four strains of bifidobacteria decreased the risk of postoperative recurrence of CD.9 Interestingly, we found that a high proportion of the endogenous microbiota (approximately 30%) in patients with CD did not belong to the dominant microbiota of healthy controls. Identification of the bacterial species or groups present in this “phylogenetic gap” could be important for understanding of the pathogenesis of CD. A description of the entire bacterial population of patients with CD, based on cloning and sequencing of 16S rDNA,23 is currently underway.

The TTGE profile of the faecal microflora was very stable over time under healthy conditions but unstable in patients. We observed only a slight decrease in the number of bands during the active phase of the disease, showing that the microflora retains a high degree of diversity in both situations. We observed no specific single band pointing to the presence of bacteria which could be specifically involved in disease activity.

A better understanding of the alterations in the microflora should help to identify therapeutic targets for antibiotics, probiotics, and prebiotics. Our results suggest that antibiotics targeting enterobacteria or bacteria responsible for the phylogenetic gap should be studied in patients with CD. Among probiotics, those containing bifidobacteria should receive special attention in trials to prevent relapse of colonic CD.

Acknowledgments

P Seksik received the Ferring-France Fellowship Grant to perform this work.

Abbreviations

CD, Crohn's disease

CDAI, CD activity index

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease

rRNA, ribosomal ribonucleic acid

TTGE, temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis

PCR, polymerase chain reaction

REFERENCES

- 1.Sartor RB. The influence of normal microbial flora on the development of chronic mucosal inflammation. Res Immunol 1997;148:567–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elson CO, Sartor RB, Tennyson GS, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1344–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Peeters M, et al. Effect of the faecal stream diversion on recurrence of Crohn's disease in the neoterminal ileum. Lancet 1991;338:771–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harper PH, Lee EC, Kettlewell MG, et al. Role of the faecal stream in the maintenance of Crohn's colitis. Gut 1985;26:279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanahan F. Inflammatory bowel disease: immunodiagnostics, immunotherapeutics, and ecotherapeutics. Gastroenterology 2001;120:622–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marteau PR, de Vrese M, Cellier CJ, et al. Protection from gastrointestinal diseases with the use of probiotics. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:430–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malchow HA. Crohn's disease and Escherichia coli. A new approach in therapy to maintain remission of colonic Crohn's disease? J Clin Gastroenterol 1997;25:653–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guslandi M, Mezzi G, Sorghi M, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii in maintenance treatment of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:1462–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campieri M, Rizzello F, Venturi A, et al. Combination of antibiotic and probiotic treatment is efficacious in prophylaxis of post-operative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a randomized controlled study vs mesalamine. Gastroenterology 2000;118:G4179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doré J, Gramet G, Goderel I, et al. Culture-independent characterisation of human feacal flora using rRNA-targeted hybridization probes. Genet Sel Evol 1998;30:287–96. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doré J, Sghir A, Hannequart-Gramet G, et al. Design and evaluation of a 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe for specific detection and quantitation of human faecal Bacteroides populations. Syst Appl Microbiol 1998;21:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alm EW, Oerther DB, Larsen N, et al. The oligonucleotide probe database. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:3557–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng D, Alm EW, Stahl DA, et al. Characterization of universal small-subunit rRNA hybridization probes for quantitative molecular microbial ecology studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 1996;62:4504–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl DA, Amann R. Development and application of nucleic acid probes. In: Stackebrant E, Goodfellow M (eds). Nucleic acid and techniques in bacterial systematics. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd, 1991:205–48.

- 15.Zoetendal EG, Akkermans AD, De Vos WM. Temperature gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of 16S rRNA from human fecal samples reveals stable and host-specific communities of active bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998;64:3854–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutren M, Michel M, de la Cochetiére MF, et al. Temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TTGE) is an appropriate tool to assess dynamics of species diversity of the human fecal flora. Reprod Nutr Dev 2000;40:176–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW. Rederived values of the eight coefficients of the Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI). Gastroenterology 1979;77:843–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, et al. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 1990;56:1919–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franks AH, Harmsen HJ, Raangs GC, et al. Variations of bacterial populations in human feces measured by fluorescent in situ hybridization with group-specific 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998;64:3336–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sghir A, Gramet G, Suau A, et al. Quantification of bacterial groups within human fecal flora by oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000;66:2263–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangin I, Bouhnik Y, Suau A, et al. Molecular analysis of the intestinal microbiota composition to evaluate the effect of PEG and lactulose laxatives in humans. Microb Ecol Health Dis 2002;14:54–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sghir A, Antonopoulos D, Mackie RI. Design and evaluation of a Lactobacillus group-specific ribosomal RNA-targeted hybridization probe and its application to the study of intestinal microecology in pigs. Syst Appl Microbiol 1998;21:291–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suau A, Bonnet R, Sutren M, et al. Direct analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA from complex communities reveals many novel molecular species within the human gut. Appl Environ Microbiol 1999;65:4799–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D'Haens GR, Geboes K, Peeters M, et al. Early lesions of recurrent Crohn's disease caused by infusion of intestinal contents in excluded ileum. Gastroenterology 1998;114:262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sartor RB. Postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: the enemy is within the fecal stream. Gastroenterology 1998;114:398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amann R, Springer N, Ludwig W, et al. Identification in situ and phylogeny of uncultured bacterial endosymbionts. Nature 1991;351:161–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stahl DA, Flesher B, Mansfield HR, et al. Use of phylogenetically based hybridization probes for studies of ruminal microbial ecology. Appl Environ Microbiol 1988;54:1079–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartley MG, Hudson MJ, Swarbrick ET, et al. Sulphasalazine treatment and the colorectal mucosa-associated flora in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1996;10:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorbach SL, Nahas L, Plaut AG, et al. Studies of intestinal microflora. V. Fecal microbial ecology in ulcerative colitis and regional enteritis: relationship to severity of disease and chemotherapy. Gastroenterology 1968;54:575–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keighley MR, Arabi Y, Dimock F, et al. Influence of inflammatory bowel disease on intestinal microflora. Gut 1978;19:1099–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darfeuille-Michaud A, Neut C, Barnich N, et al. Presence of adherent Escherichia coli strains in ileal mucosa of patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 1998;11:1405–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rembacken BJ, Snelling AM, Hawkey PM, et al. Non-pathogenic Escherichia coli versus mesalazine for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet 1999;354:635–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kruis W, Schütz E, Fric P, et al. Double-blind comparison of an oral Escherichia coli preparation and mesalazine in maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1997;11:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruis W, Fric P, Stolte M. Maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis is equally effective with Escherichia coli Nissle 1997 and with standard mesalamine. Gastroenterology 2001;120:A139. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rath HC, Ikeda JS, Linde HJ, et al. Varying cecal bacterial loads influences colitis and gastritis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. Gastroenterology 1999;116:310–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giaffer MH, Holdsworth CD, Duerden BI. The assessment of faecal flora in patients with inflammatory bowel disease by a simplified bacteriological technique. J Med Microbiol 1991;35:238–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruseler-van Embden JG, Both-Patoir HC. Anaerobic gram-negative faecal flora in patients with Crohn's disease and healthy subjects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 1983;49:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madsen KL, Doyle JS, Jewell LD, et al. Lactobacillus species prevents colitis in interleukin 10 gene-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Mahony L, Feeney M, O'Halloran S, et al. Probiotic impact on microbial flora, inflammation and tumour development in IL-10 knockout mice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2001;15:1219–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta P, Andrew H, Kirschner BS, et al. Is Lactobacillus GG helpful in children with Crohn's disease? Results of a preliminary, open-label study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;31:453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Venturi A, et al. Oral bacteriotherapy as maintenance treatment in patients with chronic pouchitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000;119:305–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Favier C, Neut C, Mizon C, et al. Fecal beta-D-galactosidase production and Bifidobacteria are decreased in Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci 1997;42:817–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]