Abstract

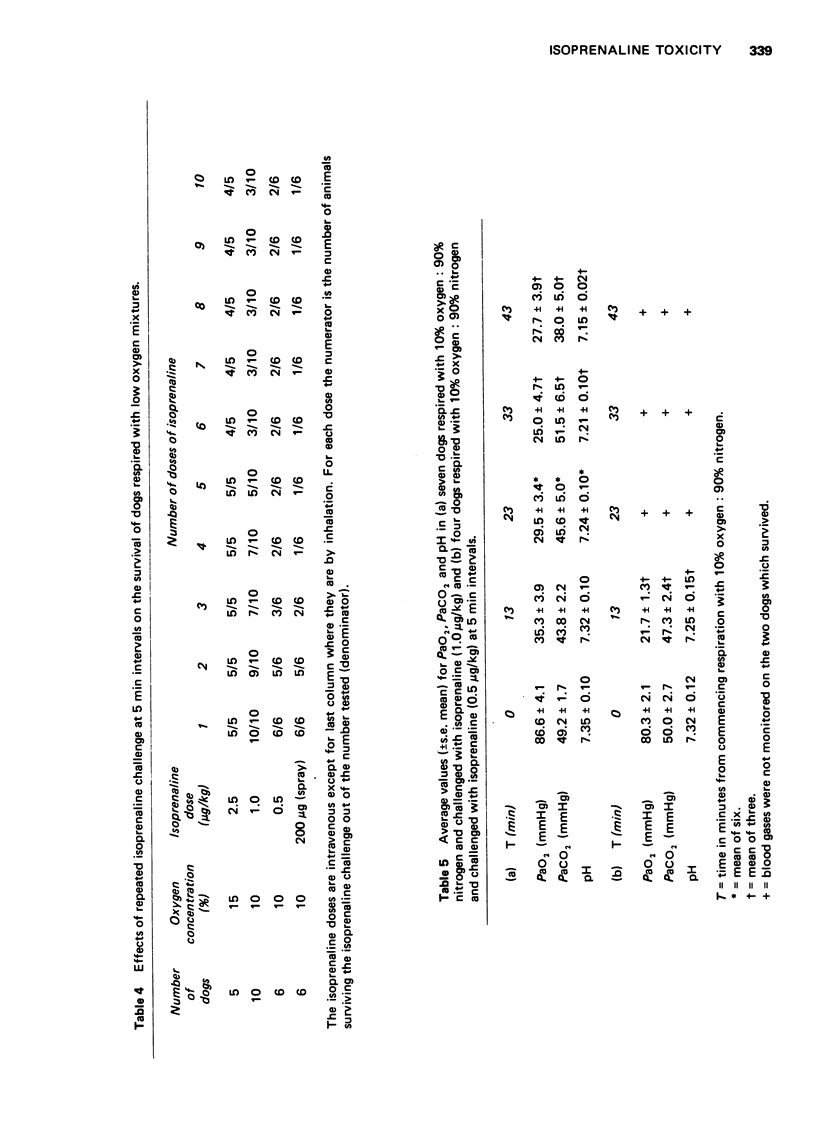

1 In dogs respired with 10% oxygen: 90% nitrogen, only five out of 16 dogs survived repeated intravenous doses of isoprenaline (either 0.5 or 1.0 μg/kg) and only one out of six dogs survived repeated isoprenaline inhalations from a pressurized aerosol.

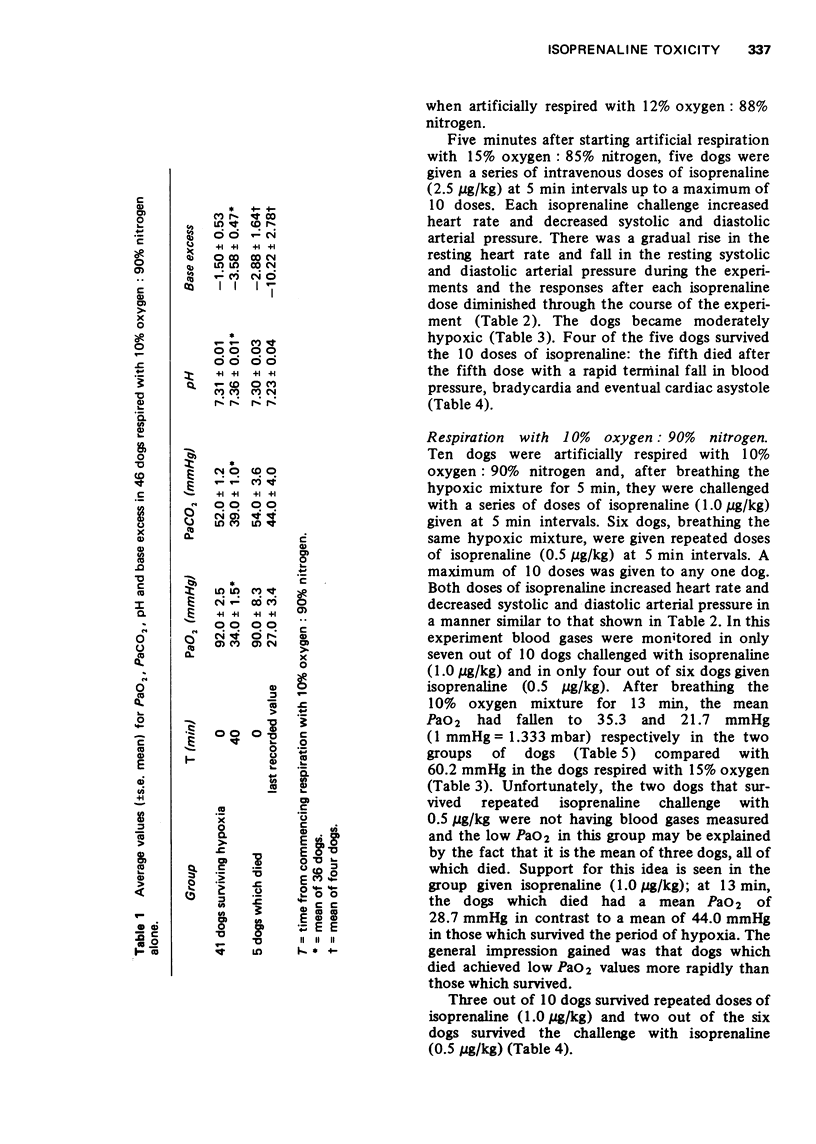

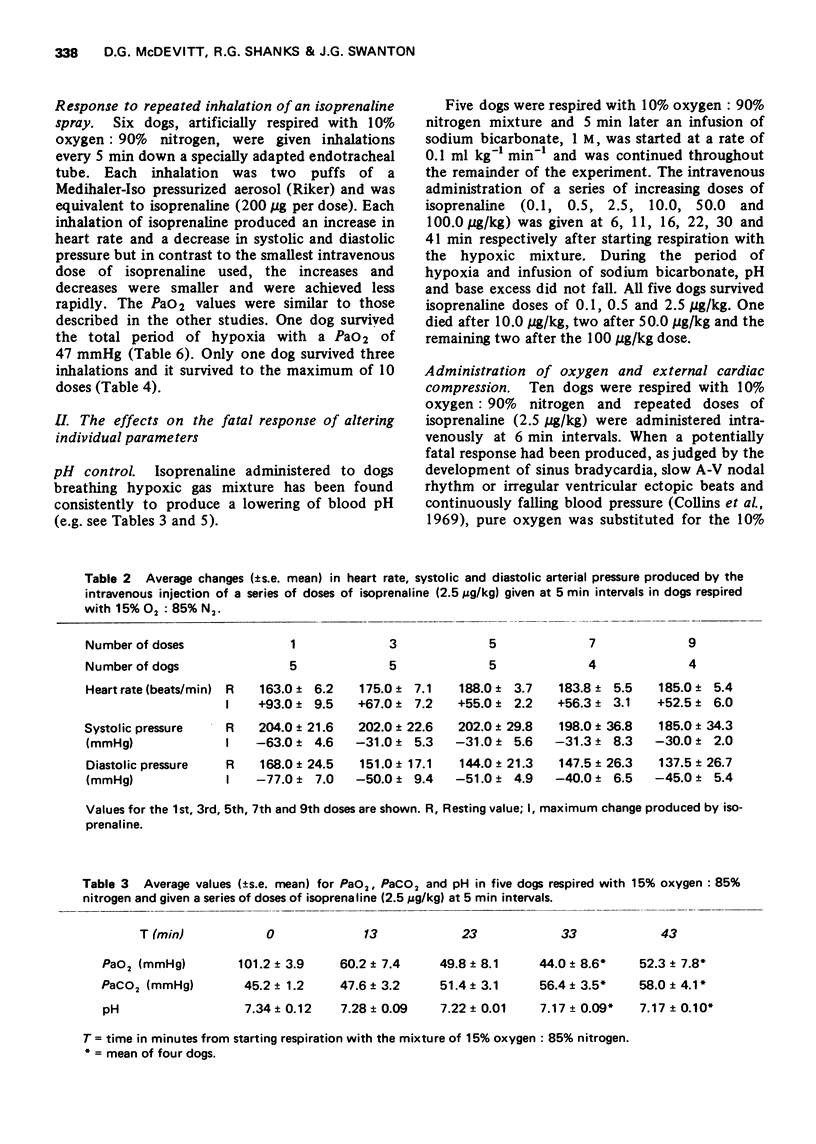

2 In dogs respired with 15% oxygen: 85% nitrogen, five out of six dogs survived repeated intravenous doses of isoprenaline (2.5 μg/kg).

3 The fatal response in these animals consisted of a fall in heart rate, arterial and pulse pressures. Sinus rhythm persisted even after the arterial pressure had fallen, though occasionally a slow A-V nodal rhythm or irregular ventricular ectopic beats occurred. Ventricular fibrillation did not occur.

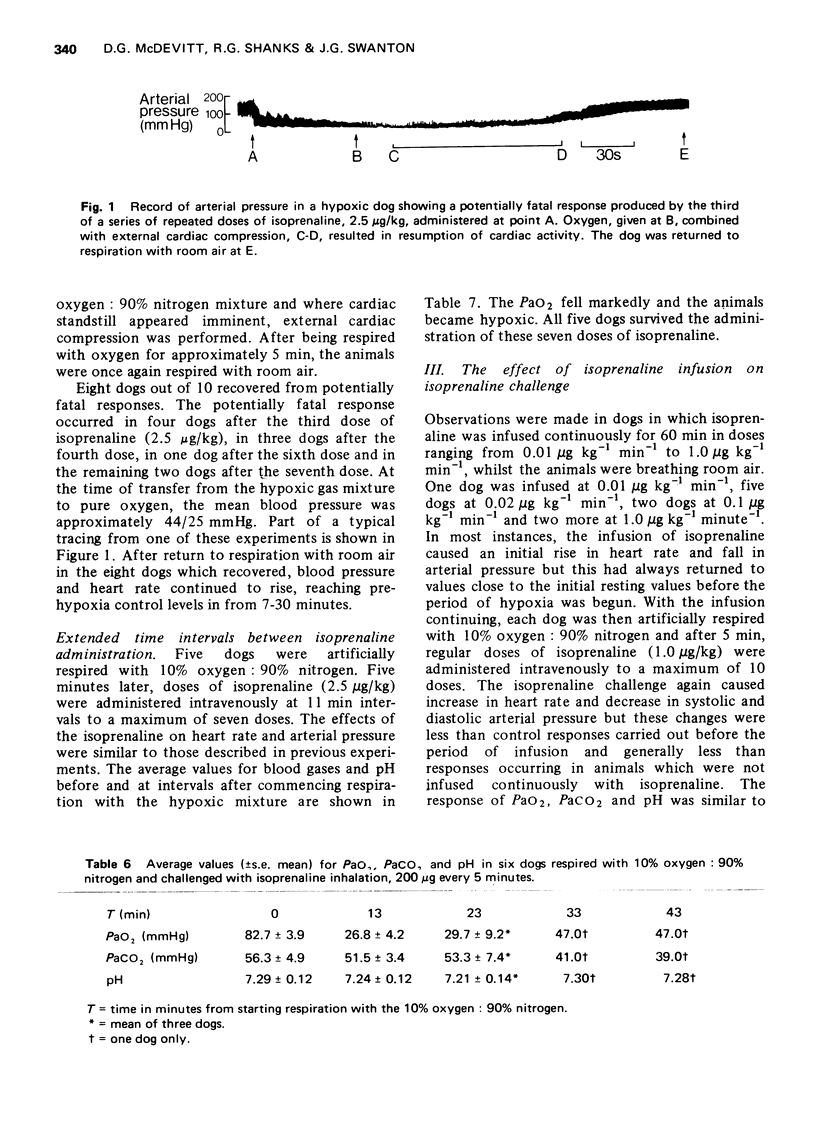

4 Eight out of 10 dogs brought to the verge of a fatal response with 10% oxygen: 90% nitrogen and repeated doses of isoprenaline (2.5 μg/kg) were resuscitated by the administration of 100% oxygen and, when necessary, cardiac massage.

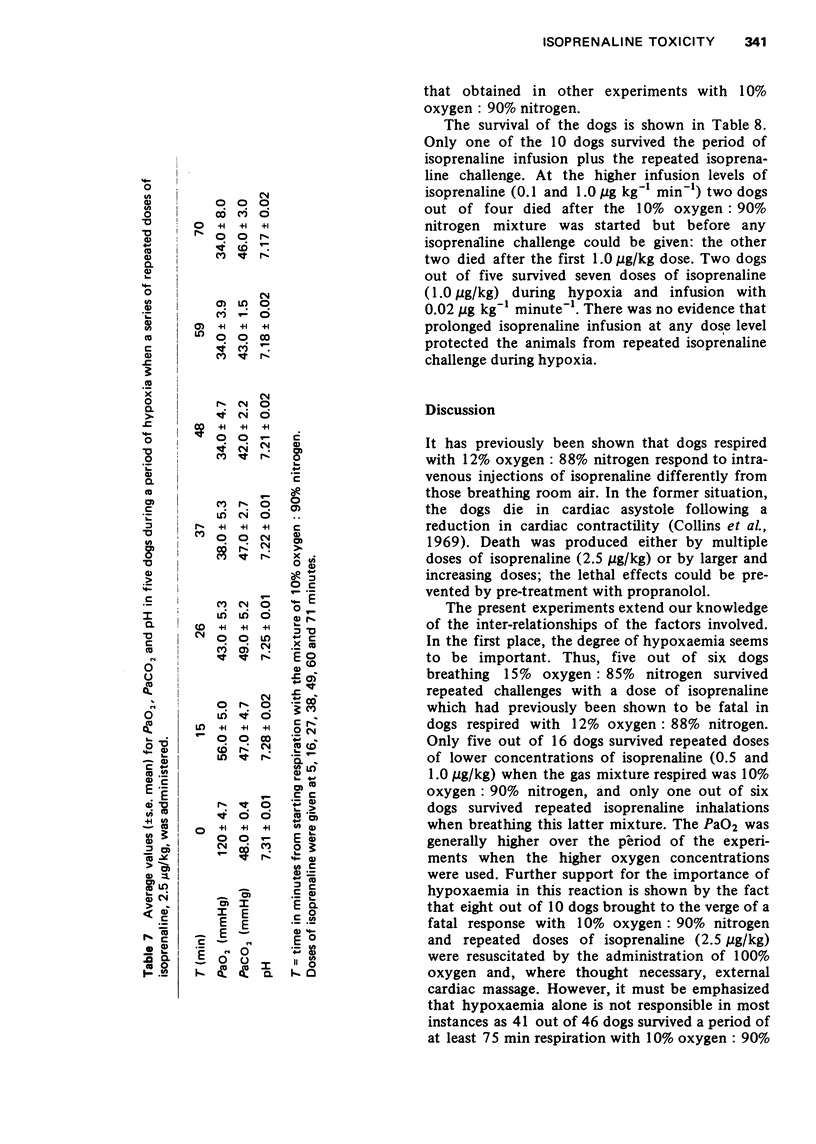

5 A group of five dogs survived the combined effects of repeated doses of isoprenaline (2.5 μg/kg) and respiration with 10% oxygen: 90% nitrogen when the time interval between doses was 11 min, instead of the usual 5 minutes.

6 Control of pH by infusion of sodium bicarbonate did not protect the dogs from the combined effects of hypoxia and repeated isoprenaline challenge.

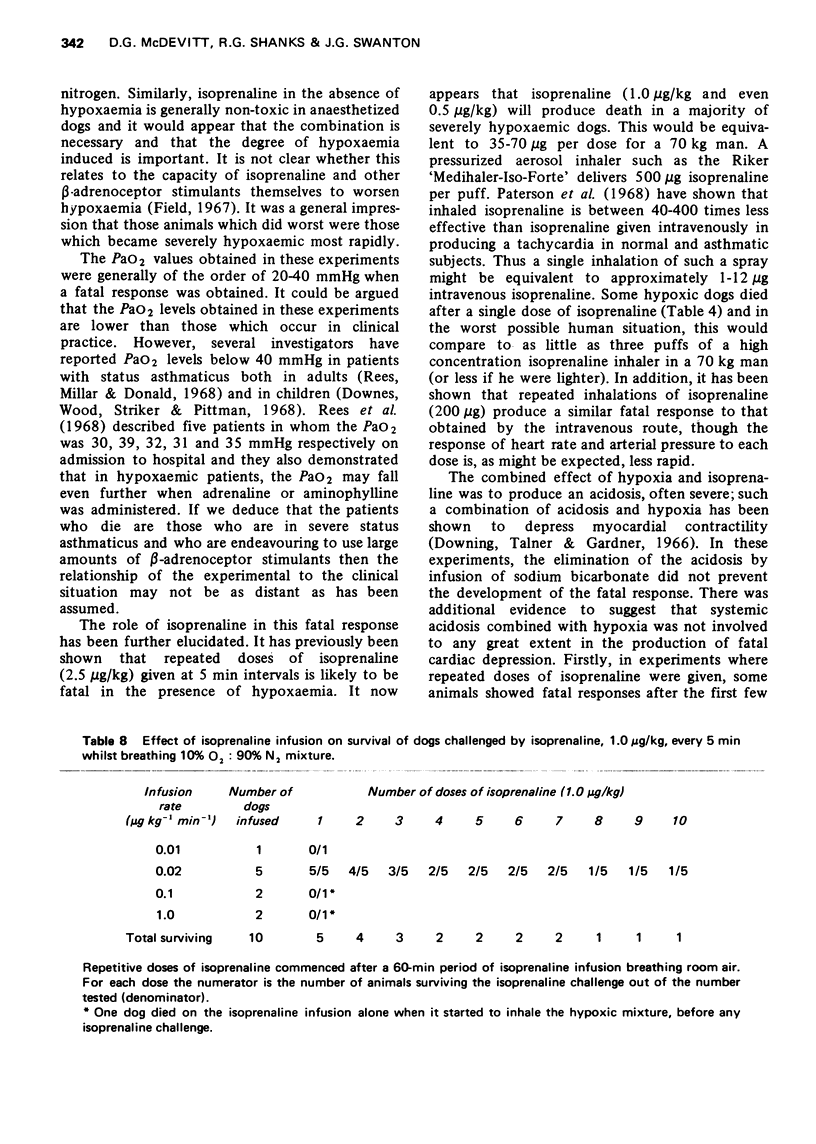

7 After a 60 min period of continuous isoprenaline infusion in dogs breathing room air, only one of 10 dogs survived artificial respiration with 10% oxygen: 90% nitrogen and repeated challenge with intravenous isoprenaline (1.0 μg/kg) at 5 min intervals. At the higher infusion levels of isoprenaline (0.1 and 1.0 μg kg-1 min-1), two dogs out of four died after the hypoxic mixture was started but before any isoprenaline challenge was given.

8 The possible relevance of these findings in dogs to the recently observed increase in mortality in young asthmatics is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ANDERSEN O. S., ENGEL K., JORGENSEN K., ASTRUP P. A Micro method for determination of pH, carbon dioxide tension, base excess and standard bicarbonate in capillary blood. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1960;12:172–176. doi: 10.3109/00365516009062419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson J. M., Rand M. J. Mutal suppression of cardiovascular effects of some beta-adrenoreceptor agonists in the cat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1968 Dec;20(12):916–922. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conolly M. E., Davies D. S., Dollery C. T., George C. F. Resistance to -adrenoceptor stimulants (a possible explanation for the rise in ashtma deaths). Br J Pharmacol. 1971 Oct;43(2):389–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollery C. T., Davies D. S., Draffan G. H., Williams F. M., Conolly M. E. Blood concentrations in man of fluorinated hydrocarbons after inhalation of pressurised aerosols. Lancet. 1970 Dec 5;2(7684):1164–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing S. E., Talner N. S., Gardner T. H. Influences of hypoxemia and acidemia on left ventricular function. Am J Physiol. 1966 Jun;210(6):1327–1334. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field G. B. The effects of posture, oxygen, isoproterenol and atropine on ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lung in asthma. Clin Sci. 1967 Apr;32(2):279–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman W. H., Adelstein A. M. Rise and fall of asthma mortality in England and Wales in relation to use of pressurised aerosols. Lancet. 1969 Aug 9;2(7615):279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)90051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley P. J., Littlejohns D. W., Prichard B. N. Isoprenaline-induced tachycardia in man. Br J Pharmacol. 1972 Nov;46(3):539P–540P. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker S. S., Choo-Kang Y. F., Cooper E. J., Cameron S. J., Grant I. W. Bronchodilator effect of oral salbutamol in asthmatics treated with corticosteroids. Br Med J. 1971 Oct 16;4(5780):139–142. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5780.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson J. W., Conolly M. E., Davies D. S., Dollery C. T. Isoprenaline resistance and the use of pressurised aerosols in asthma. Lancet. 1968 Aug 24;2(7565):426–429. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pun L. Q., McCulloch M. W., Rand M. J. Bronchodilator effects of sympathomimetic amines given singly and in combination. Eur J Pharmacol. 1971 Apr;14(2):140–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(71)90207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees H. A., Millar J. S., Donald K. W. A study of the clinical course and arterial blood gas tensions of patients in status asthmaticus. Q J Med. 1968 Oct;37(148):541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer F. E., Doll R., Heaf P., Strang L. B. Investigation into use of drugs preceding death from asthma. Br Med J. 1968 Feb 10;1(5588):339–343. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5588.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolley P. D. Asthma mortality. Why the United States was spared an epidemic of deaths due to asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1972 Jun;105(6):883–890. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1972.105.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. J., 4th, Harris W. S. Cardiac toxicity of aerosol propellants. JAMA. 1970 Oct 5;214(1):81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]