Abstract

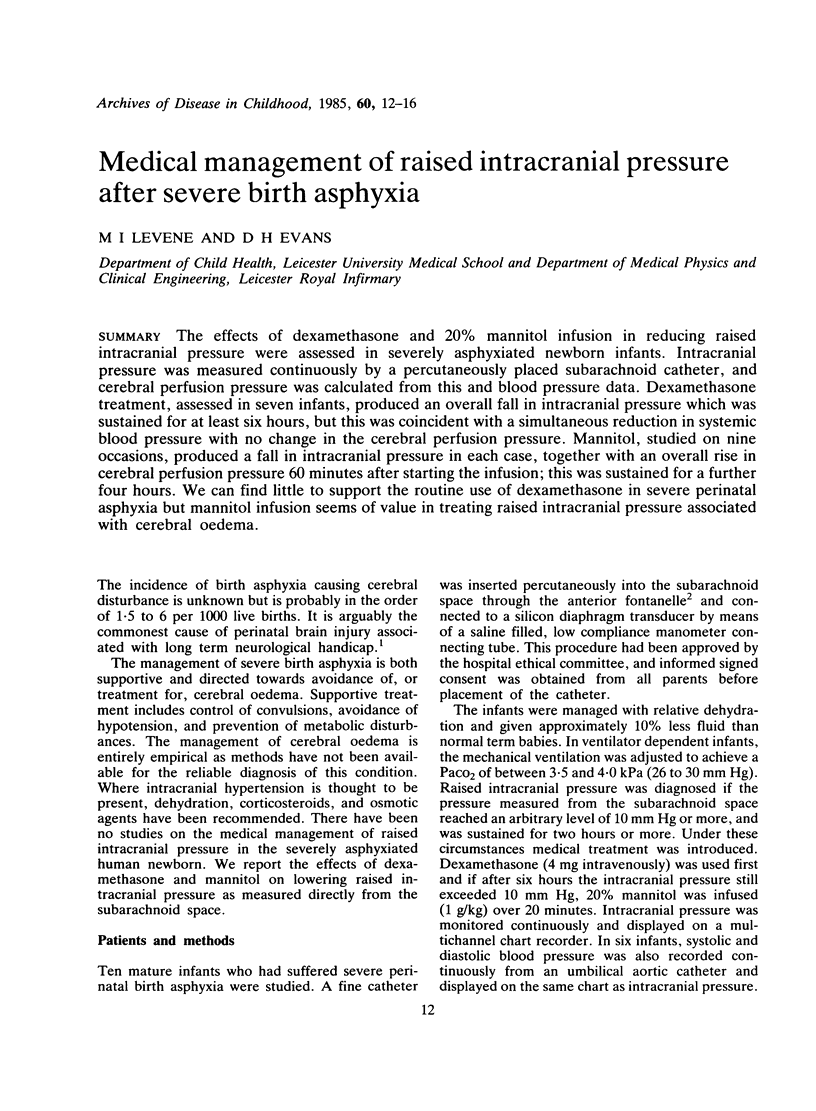

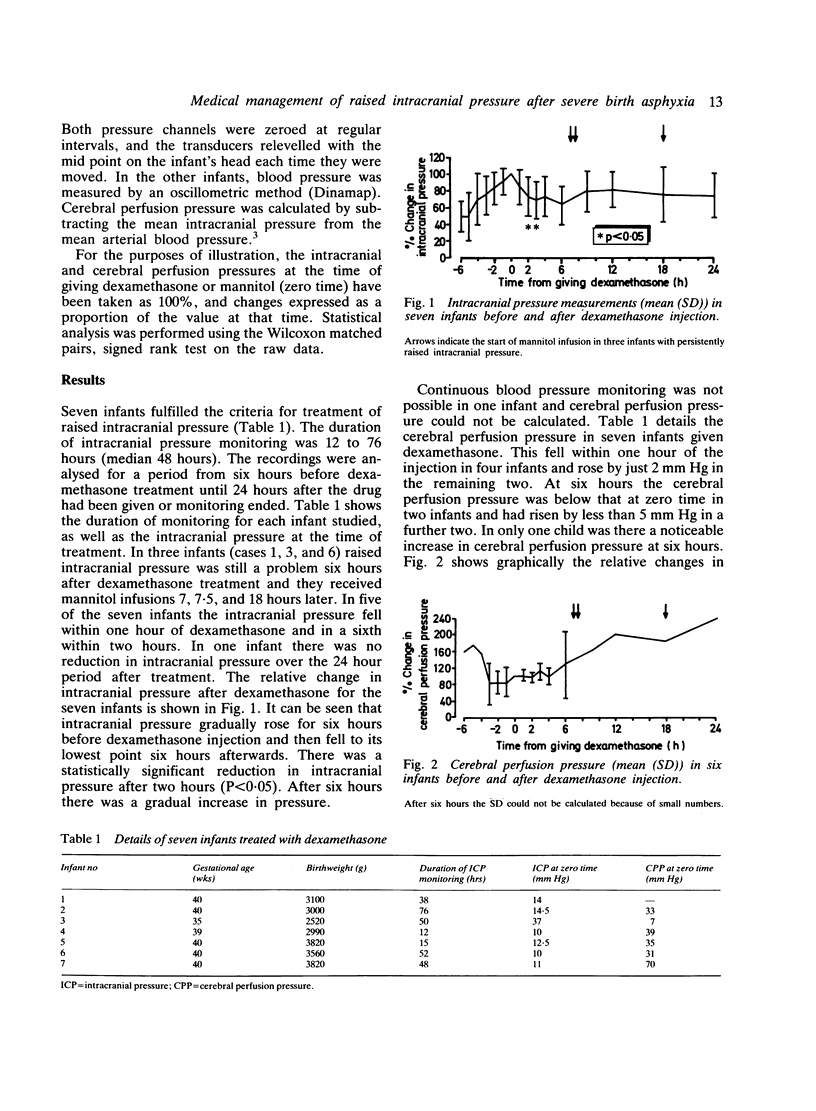

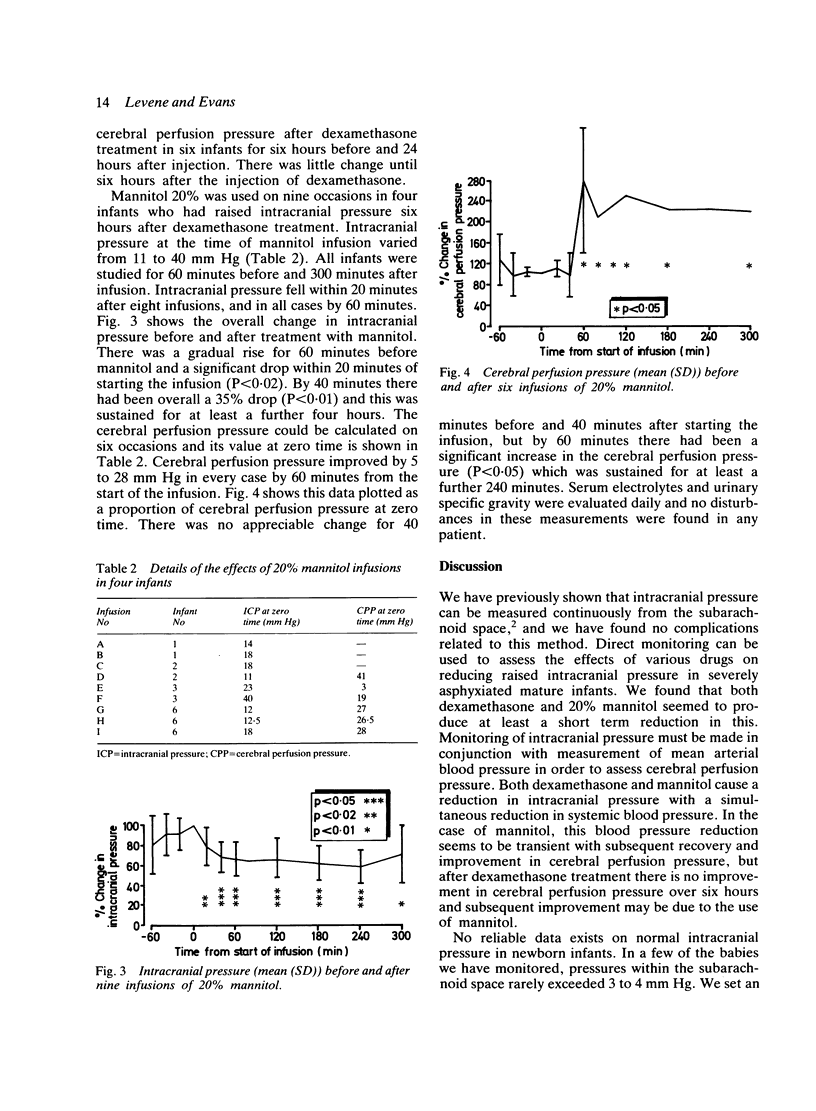

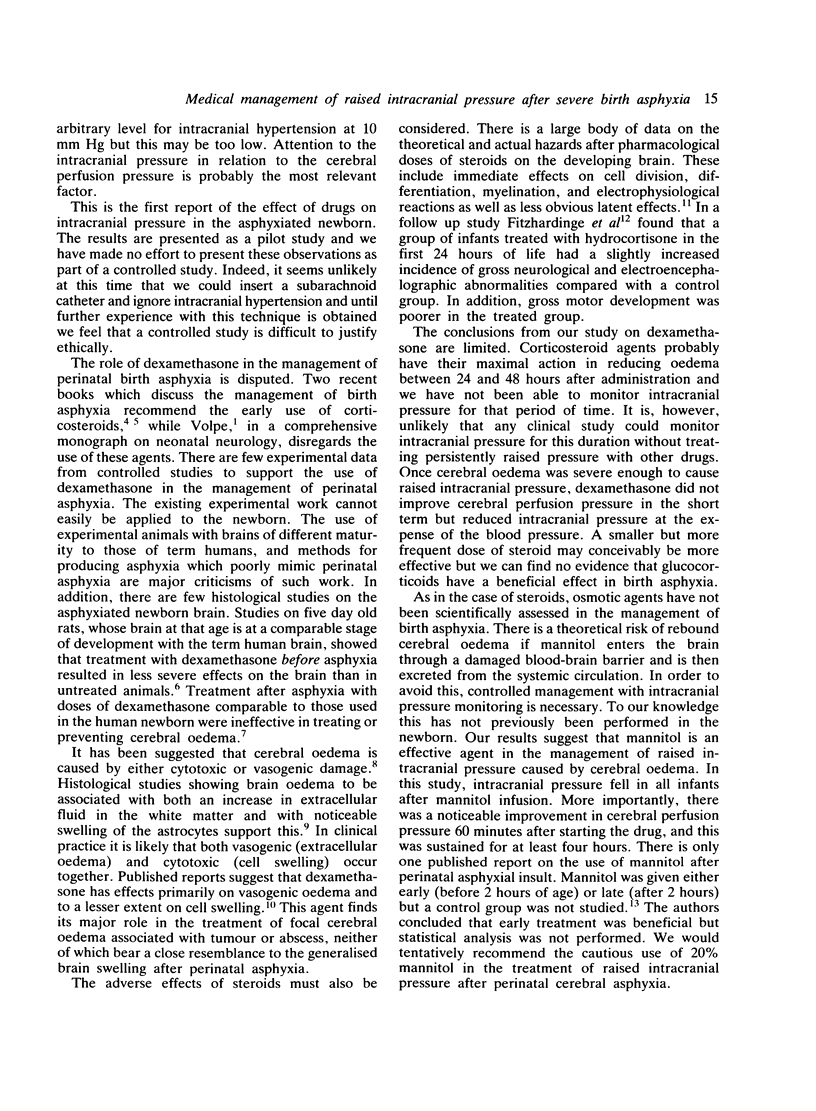

The effects of dexamethasone and 20% mannitol infusion in reducing raised intracranial pressure were assessed in severely asphyxiated newborn infants. Intracranial pressure was measured continuously by a percutaneously placed subarachnoid catheter, and cerebral perfusion pressure was calculated from this and blood pressure data. Dexamethasone treatment, assessed in seven infants, produced an overall fall in intracranial pressure which was sustained for at least six hours, but this was coincident with a simultaneous reduction in systemic blood pressure with no change in the cerebral perfusion pressure. Mannitol, studied on nine occasions, produced a fall in intracranial pressure in each case, together with an overall rise in cerebral perfusion pressure 60 minutes after starting the infusion; this was sustained for a further four hours. We can find little to support the routine use of dexamethasone in severe perinatal asphyxia but mannitol infusion seems of value in treating raised intracranial pressure associated with cerebral oedema.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adlard B. P., De Souza S. W. Influence of asphyxia and of dexamethasone on ATP concentrations in the immature rat brain. Biol Neonate. 1974;24(1):82–88. doi: 10.1159/000240636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza S. W., Dobbing J. Cerebral oedema in developing brain. 3. Brain water and electrolytes in immature asphyxiated rats treated with dexamethasone. Biol Neonate. 1973;22(5):388–397. doi: 10.1159/000240571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhardinge P. M., Eisen A., Lejtenyi C., Metrakos K., Ramsay M. Sequelae of early steroid administration to the newborn infant. Pediatrics. 1974 Jun;53(6):877–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatzo I. Presidental address. Neuropathological aspects of brain edema. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1967 Jan;26(1):1–14. doi: 10.1097/00005072-196701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levene M. I., Evans D. H. Continuous measurement of subarachnoid pressure in the severely asphyxiated newborn. Arch Dis Child. 1983 Dec;58(12):1013–1015. doi: 10.1136/adc.58.12.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long D. M., Hartmann J. F., French L. A. The response of experimental cerebral edema to glucosteroid administration. J Neurosurg. 1966 May;24(5):843–854. doi: 10.3171/jns.1966.24.5.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju T. N., Vidyasagar D., Papazafiratou C. Cerebral perfusion pressure and abnormal intracranial pressure wave forms: their relation to outcome in birth asphyxia. Crit Care Med. 1981 Jun;9(6):449–453. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichsel M. E., Jr The therapeutic use of glucocorticoid hormones in the perinatal period: potential neurological hazards. Ann Neurol. 1977 Nov;2(5):364–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410020503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]