Abstract

Periconceptional undernutrition alters fetal growth, metabolism and endocrinology in late gestation. The underlying mechanisms remain uncertain, but fetal exposure to excess maternal glucocorticoids has been hypothesized. We investigated the effects of periconceptional undernutrition on maternal hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function and placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11βHSD2) activity. Ewes received maintenance feed (N, n = 20) or decreased feed from −60 to +30 days from mating to achieve 15% weight loss after an initial 2-day fast (UN, n = 21). Baseline plasma samples and arginine vasopressin (AVP)–corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) challenges were performed on days −61, −57, −29, −1, +29, 33, and 49 from mating (day 0). Maternal adrenal and placental tissue was collected at 50 days. Baseline plasma levels of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol decreased in the UN group (P < 0.0001). ACTH response to AVP–CRH was greater in UN ewes during undernutrition (P = 0.03) returning to normal levels after refeeding. Cortisol response to AVP–CRH was greater in UN ewes after the initial 2-day fast, but thereafter decreased and was lower in UN ewes from mating until the end of the experiment (P = 0.007). ACTH receptor, StAR and p450c17 mRNA levels were down-regulated in adrenal tissue from UN ewes. Placental 11βHSD2 activity was lower in UN than N ewes at 50 days (P = 0.014). Moderate periconceptional undernutrition results in decreased maternal plasma cortisol concentrations during undernutrition and after refeeding, and adrenal resistance to ACTH for at least 20 days after refeeding. Fetal exposure to excess maternal cortisol is unlikely during the period of undernutrition, but could occur later in gestation if maternal plasma cortisol levels return to normal while placental 11βHSD2 activity remains low.

Manipulation of maternal diet can alter metabolism of the offspring in ways that may increase susceptibility to disease in adulthood (Harding, 2001). However, the mechanisms that underlie these processes are not well defined. The potential role of glucocorticoids has been extensively investigated because of their known influence on fetal growth and development. In animal experiments, in utero exposure to exogenous glucocorticoids has resulted in decreased fetal (Benediktsson et al. 1993; Jobe et al. 1998) and postnatal (Ikegami et al. 1997) growth, increased blood pressure (Dodic et al. 1998), postnatal hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinaemia (Lindsay et al. 1996; Nyirenda et al. 1998; Nyirenda et al. 2001) and altered fetal (Sloboda et al. 2000) and postnatal (Welberg et al. 2000; Sloboda et al. 2002) hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis regulation, outcomes that are also seen after maternal undernutrition (Harding, 2001). It has therefore been hypothesized that inappropriate fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids could mediate the long-term effects of maternal undernutrition on the fetus.

Fetal exposure to excess glucocorticoids in response to maternal undernutrition could potentially occur if baseline maternal glucocorticoid concentrations were elevated, if there was exaggerated responsiveness of the maternal HPA axis leading to intermittent elevation of maternal glucocorticoid concentrations, or if the placental mechanisms that normally regulate maternal–fetal transport of glucocorticoids were altered in a way that allowed more maternal glucocorticoid to cross the placenta. However evidence supporting these different possibilities is conflicting and they have not been examined systematically in the same experiment.

While studies of acute starvation in a variety of species commonly show a rise in plasma glucocorticoid concentrations (Stewart et al. 1988; Douyon & Schteingart, 2002), the response to prolonged undernutrition of mild or moderate severity is less uniform and not consistent across different species. Four weeks of food restriction to 50%ad libitum intake in rats resulted in increased plasma corticosterone concentration (Garcia-Belenguer et al. 1993). Moderate undernutrition in the last week of gestation in rats resulted in increased maternal and neonatal corticosterone concentrations and decreased birth weight (Lesage et al. 2001). Plasma cortisol concentrations were elevated in ewes undernourished for 10 days in late gestation. However, this elevation in plasma cortisol concentration did not persist when the duration of undernutrition was extended to 20 days, suggesting adaptation to the new plane of nutrition over time (Edwards & McMillen, 2001). Pregnant ewes undernourished over a more prolonged period, from 28 to 80 days of gestation, had consistently lower plasma cortisol concentrations than normally nourished controls during the period of undernutrition (Bispham et al. 2003), as did sheep undernourished from 60 days before to 30 days after mating (Bloomfield et al. 2004).

Maternal undernutrition could also result in excess fetal glucocorticoid exposure if there was an enhanced responsiveness of the maternal HPA axis at any level, leading to intermittent high peak concentrations of maternal glucocorticoids despite normal baseline concentrations. Altered HPA maturation and responsiveness has been demonstrated in the fetuses of ewes undernourished in the periconceptional period (Bloomfield et al. 2004). However, there are few data regarding the effect of undernutrition in pregnancy on regulation of the maternal HPA axis.

Placental transfer of maternal glucocorticoid in mammals is regulated predominantly by placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11βHSD2), which converts cortisol (in humans and sheep) or corticosterone (in the rat) to biologically inactive cortisone, thereby controlling fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoid. A low protein diet throughout pregnancy in rats decreased placental 11βHSD2 activity (Gardner et al. 1998). Offspring in the low protein group became hypertensive later in life, an effect that was prevented by blocking maternal glucocorticoid synthesis (Langley-Evans, 1997a). Undernutrition in early to mid gestation in sheep also resulted in a 50% decrease in placental 11βHSD2 expression at 77 days (Whorwood et al. 2001). Ewes undernourished for a prolonged period starting at 26 days of gestation had decreased placental 11βHSD2 activity at days 90 and 135. Shorter periods of undernutrition before conception or in early, mid or late gestation had no significant effect on NAD+-dependent 11βHSD2 activity but were associated with a decreased cortisol: cortisone ratio in fetal plasma, suggesting that undernutrition may affect fetal glucocorticoid regulation independently of direct exposure to maternal glucocorticoid (McMullen et al. 2004).

We have previously shown that fetuses of ewes that underwent moderate, prolonged undernutrition around the time of conception had altered growth (Harding, 2001), metabolism (Oliver et al. 2001, 2005), and insulin secretion (Oliver et al. 2001), accelerated maturation of the HPA axis (Bloomfield et al. 2004) and reduced length of gestation (Bloomfield et al. 2003b). The aim of this experiment was to explore to what extent fetal exposure to excess maternal glucocorticoids might provide an underlying mechanism to explain these findings. Specifically, we aimed to determine the effects of maternal undernutrition from 60 days before until 30 days after conception and subsequent refeeding on maternal plasma concentrations of ACTH and cortisol, responsiveness of the maternal HPA axis to stimulation, and placental 11βHSD2 activity.

Methods

Animal care and nutrition

Romney ewes, 4–5 years old, were acclimatized to indoor conditions and housed in adjacent individual pens with open mesh sides for at least 10 days prior to the start of the experiment. All ewes were fed once daily with the same complete feed (Country Harvest stock feed, Cambridge, New Zealand; main ingredient lucerne with maize, salt and mineral premix) (Oliver et al. 2005). Ewes had free access to water and were weighed twice weekly. From 61 days before mating, ewes were randomly assigned to receive either maintenance feed (‘N’ group; fed to maintain body weight within 5% of start weight, n = 20) or decreased feed (‘UN’ group; fasted for 2 days, then the daily amount of feed calculated individually to achieve and maintain a 15% weight loss until 30 days after mating, then fed ad libitum until the end of the experiment at 50 days, n = 21).

Oestrous was synchronized with progesterone containing intravaginal devices (CIDRs) inserted 16 days before mating. Intramuscular serum gonadotrophin (400 IU Folligon, Intervet, Auckland, New Zealand) was given to stimulate ovulation when the CIDRs were removed 2 days before mating. Five ewes in each nutritional group were not mated but underwent all other manipulations to provide a non-pregnant control group.

At the end of the experiment, ewes were killed by captive bolt stunning and exsanguination. Placentomes and maternal adrenal glands were collected and frozen immediately on dry ice, then stored at −80°C. Fetal blood was collected via the umbilical vessels and centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m (1200g). and the plasma stored at −20°C.

All experiments were approved by the University of Auckland Animal Ethics Committee.

Sampling and analysis

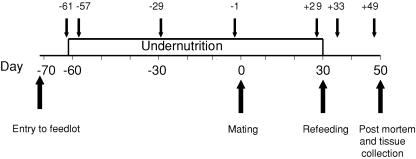

Jugular venous catheters, from which frequent blood samples could be taken with minimal stress to the animal, were inserted under local anaesthesia at least the day before each sampling period. All baseline blood samples were taken between 07.30 h and 09.30 h, prior to the daily feed. Sampling occurred at the start of undernutrition (61 and 57 days before mating), at 29 days and 1 day before mating and 29 days after mating, post-refeeding on day 33 and at the end of the experiment (49 days after mating). (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Experimental outline.

Small arrows indicate day of AVP–CRH challenge tests.

A AVP–CRH challenge was performed after each baseline blood sample. A combined equimolar injection of 0.1 μg kg−1 ovine arginine vasopressin (AVP) (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and 0.5 μg kg−1 bovine corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH) (Sigma) was given into the venous catheter and blood samples taken 15, 30, 45, 60, 120 and 240 min post-injection (Brooks & Challis, 1989). Blood samples were centrifuged at 3000 r.p.m. at 4°C and the plasma stored at −20°C until analysis. Adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) was measured using a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) that has previously been validated for use in sheep (Jeffray et al. 1998); inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 9.5% (n = 22) and 16.5% (n = 16), respectively. For practical reasons not all samples were analysed for ACTH.

Cortisol was measured using mass spectrometry. Internal standard (IS: 50 μl of 11-dehydrocorticosterone, 100 ng ml−1 in 50% methanol) was added to 100 μl plasma. Glucocorticoids were extracted using 4 ml of water-saturated diethylether containing 5% by volume of 0.1% ascorbic acid. Samples were dried, re-suspended in 250 μl methanol, dried under vacuum and resuspended in toluene: acetone 50: 50 before transfer to HPLC injector vials. Twenty microlitres was injected onto an HPLC mass spectrometer system consisting of a Surveyor MS pump and autosampler followed by an Ion Max APCI source on a Finnigan TSQ Quantum Ultra AM triple quadrapole mass spectrometer all controlled by Finnigan Xcaliber software (Thermo Electron Corporation, San Jose, CA, USA). The mobile phase was 80% methanol and was isocratic, flowing at 600 μl min−1 through a Luna 3μC18(2) 100A 250 × 4.6 column at 35°C (Phenomenex, Auckland, New Zealand). Retention times (Rt) were 5.4 min for the IS and 5.6 min for cortisol. Ionization was in positive mode; Q2 had 0.7 mTorr of argon. The mass transitions followed were 245.1→121.1 at 28 V for IS and 363→121 at 30 V for cortisol. Mean inter- and intra-assay CV values were 6.4% (n = 37) and 13.7% (n = 37), respectively.

ACTH-R, StAR and P450c17 mRNA levels of ACTH receptor (ACTH-R), steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR) and the key regulatory enzyme in cortisol production, P450c17, were measured in maternal adrenal tissue by real-time RT-PCR. Total RNA was extracted by the Trizol method (Gibco BRL, Life technologies, New Zealand). The final concentration of RNA was quantified using spectrophotometric OD260 measurements and purity was assessed by OD260/OD280 ratio, with values > 1.9 being of acceptable purity.

Expression levels were quantified using a one-step PCR reaction. Briefly, RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I (Invitrogen NZ Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) before RT-PCR to eliminate any potential genomic DNA. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript™. First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen NZ Ltd) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All reactions were treated with RNase H before real-time PCR. PCR amplification was performed in triplicate on an ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the standard cycling conditions recommended by the manufacturer (50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min). Singleplex amplification was carried out in 384-well plates with a total reaction volume of 20 μl, containing 10 μl of TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 1 μl of cDNA template, 250 nm of the probe and 900 nm of forward and reverse primers. A standard curve of the target gene and 18S rRNA were included in each plate, consisting of 2-fold serial dilutions of cDNA synthesized from stock adrenal tissue from pregnant sheep of identical gestational age. Real-time PCR efficiencies (E) were calculated from the slopes of the standard curves for each target gene (E = 10−1/slope). Samples from the N group were selected as a calibrator. Gene expression in the undernourished group were expressed relative to the calibrator and as a ratio to 18S rRNA using the formula (Pfaffl, 2001):

where Etarget is the real-time PCR amplification efficiency of target gene transcript; E18S is the real-time PCR amplification efficiency of 18S rRNA; and ΔCPtarget(N–UN) and ΔCP18S(N–UN) are the cycle threshold differences between the calibrator (the N group) and UN group for the target gene and 18S rRNA, respectively. Data for real time PCR are therefore expressed as relative expression ratios for the UN group to the N group with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Oligonucleotide primers and probe design

Available ovine sequences for ACTH-R, StAR and P450c17 in GenBank were analysed using the Primer Express™ software (Applied Biosystems) to determine optimum primer and probe locations. A BLAST search was conducted to ensure that primers and probes were not constructed from any homologous regions that would encode for other proteins, and the specificity of the PCR product was confirmed by high-resolution gel electrophoresis to verify that the transcripts were of the predicted molecular size. Each probe was labelled at the 5′ end with fluorescein (for the target gene) or VIC (for ribosomal 18S RNA) and at the 3′ end with a minor groove-binder and a non-fluorescent quencher. Primers and probes for target genes were manufactured by Invitrogen NZ Ltd and Applied Biosystems, respectively. The probe and primer for ribosomal 18S RNA (18S rRNA) were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Assay-on-Demand™, Applied Biosystems). ACTH-R (1023 bp; accession AF116874) forward and reverse primers were constructed from bp 368 to 392 with a sequence of TTGGAAAATGTTCTGATCATGTTCA and from bp 421–443 with a sequence of CATCTGCTGTGCTTTCAAAACTG, respectively. The probe for ACTH-R was located between bp 399 and 415 with a sequence of TGGGTTACCTCGAGCCT. StAR (1152 bp; accession AF290202) forward and reverse primers were constructed from bp 543–564 with a sequence of AAGGTCCTGCAGAAGATT and from bp 585–602 with a sequence of CGCCTCTGCAGCCAACTC, respectively. The probe for StAR was located between bp 566 and 583 with a sequence of AGACACTATCATCACTCA. P450c17 (1728 bp; accession L40335) forward and reverse primers were constructed from bp 806–826 with a sequence of TTCACCAGCGACGCCATCACT and from bp 854–878 with a sequence of TGTTGTTATTGTCTGCATTCACCTT, respectively. The probe for P450c17 was located between bp 828 and 843 with a sequence of ACTTGCTGCACATACT.

Assay of 11βHSD2 activity

11βHSD2 activity was determined by thin layer chromatography, measuring the rate of conversion of cortisol to cortisone (Yang et al. 1994).

Preparation of tissue homogenates

Placental tissues (1 mg) were homogenized in four volumes of ice-cold homogenization buffer (50 mm HCl, 50 mm EDTA, 2 mm DTT, 2 mm PMSF, 2 mm sucrose), pH 7.4. The homogenate was used immediately in the 11βHSD2 activity assay.

Assay of 11βHSD2 activity

11βHSD2 was measured by the rate of conversion of cortisol to cortisone. Briefly, placental tissue homogenates were incubated with 10−8 m [3H]cortisol and 10−3 m NAD+ for 120 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with the addition of 500 μl of ethyl acetate. The steroids were extracted with 3 ml ethyl acetate and 40 μg mixture of non-radioactive cortisol and cortisone as carrier steroids. The extracts were air-dried and reconstituted in 100 μl ethyl acetate. Twenty-five microlitres of each sample was counted to determine the percent recovery of the samples after thin layer chromatography (TLC). An additional 25 μl of the resuspension was spotted on a TLC plate which was developed in chloroform/ethanol (95: 5). The bands containing the labelled cortisol and cortisone were visualized under UV light by the non-radioactive carriers, scraped off TLC plates, reconstituted in 4 ml ethyl acetate and added to scintillation vials. The resuspension was air-dried and after scintillation fluid was added, the radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. From the specific activity of the labelled cortisol and the radioactivity of the cortisone, the rate of cortisol to cortisone conversion was calculated and expressed as the amount of cortisone (pmol) formed per minute per mg protein.

Statistics

Baseline cortisol and ACTH concentrations were compared using repeated measures ANOVA. For the stimulation tests, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for both ACTH and cortisol using a triangulation method from a baseline of zero and compared using factorial ANOVA with Fisher's post hoc test. Effects are reported for nutritional group (N versus UN), time and group–time interaction (significant effect P < 0.05). Values are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

Forty-one ewes completed the experiment. In the 31 mated ewes, there was no significant difference between nutritional groups in pregnancy rate or outcome, with eight singletons, five multiple pregnancies and two non-pregnant in the N group (total n = 15) and five singletons, seven multiple pregnancies and four non-pregnant sheep in the UN group (total n = 16).

Ewe weight was similar in both nutritional groups at the start of the experiment (Table 1). N ewes gained an average of 8.5 ± 0.4 kg (8%) during the experiment. UN ewes lost weight over the first 45 days. Weight was then stable from the time of CIDR insertion 16 days before mating until refeeding (total weight loss 10.8 ± 0.3 kg (18%) from the start of the experiment to the time of refeeding). Average weight gain from refeeding to 50 days in the UN group was 7.7 ± 0.4 kg, so that these ewes had not regained their start weight by the end of the experiment. Mean intake to refeeding in UN ewes was 28% of N intake.

Table 1.

Weights and feed intake of well nourished (N) and undernourished (UN) ewes during the study period

| N n = 20 | UN n = 21 | |

|---|---|---|

| Day −61 | 58.6 ± 0.5 | 59.4 ± 0.9 |

| Day −30 | 62.0 ± 0.8 | 51.7 ± 0.8 |

| Day −16 | 62.7 ± 0.7 | 49.6 ± 0.8 |

| Day −2 | 64.1 ± 0.8 | 49.7 ± 0.9 |

| Day +29 | 66.5 ± 0.6 | 48.6 ± 0.8 |

| Day +50 | 67.1 ± 0.7 | 56.3 ± 0.7 |

| Daily feed intake day −60 to +29 | 1.44 ± 0.08 | 0.4 ± 0.01 |

Values are means (kg) ± s.e.m. Group–time interaction for weight P < 0.0001. Mean daily feed intake different between nutritional groups P < 0.0001.

No differences were found in baseline or stimulated cortisol and ACTH data between pregnant and non-pregnant ewes, or between ewes with singleton and multiple pregnancies (Table 2). Thus, only differences between nutritional groups are reported.

Table 2.

Baseline plasma concentrations of ACTH and cortisol and response to AVP–CRH challenge in well nourished (N) and undernourished (UN) ewes

| ACTH (pmol l−1) | ACTH AUC (pmol min l−1) | Cortisol (nmol l−1) | Cortisol AUC (nmol min l−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day | N | UN | N | UN | N | UN | N | UN |

| −61 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 11.8 ± 1.9 | 5393 ± 669 | 4595 ± 492 | 18 ± 2 | 32 ± 5 | 19790 ± 1053 | 20290 ± 1346 |

| −56 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 10.3 ± 1.3 | 4353 ± 495 | 5667 ± 838 | 17 ± 2 | 29 ± 4 | 17861 ± 751 | 22662 ± 2454 |

| −29 | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | — | — | 16 ± 3 | 10 ± 1 | — | — |

| −1 | 7.4 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4296 ± 260 | 7458 ± 691 | 19 ± 3 | 6 ± 1 | 18897 ± 1495 | 14674 ± 1039 |

| +29 total | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 6178 ± 541 | 8510 ± 1421 | 17 ± 3 | 7 ± 1 | 21960 ± 1301 | 14646 ± 1018 |

| S | 7.5 ± 1.4 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 5841 ± 496 | 11333 ± 4746 | 16 ± 3. | 7 ± 1 | 22894 ± 2770 | 13549 ± 1593 |

| M | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 6778 ± 1738 | 7442 ± 1226 | 17 ± 9 | 6 ± 1 | 23045 ± 2499 | 16875 ± 1291 |

| +34 | 6.1 ± 1.0 | 4.0 ± 0.6 | — | — | 14 ± 2 | 8 ± 1 | — | — |

| +49 total | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 4927 ± 365 | 5774 ± 657 | 15 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | 17220 ± 692 | 14696 ± 695 |

| S | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 5248 ± 411 | 5536 ± 1382 | 10 ± 2 | 11 ± 3 | 17851 ± 1029 | 15186 ± 1024 |

| M | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 4488 ± 671 | 5097 ± 629 | 15 ± 4 | 7 ± 1 | 16830 ± 1251 | 15125 ± 1167 |

AUC: area under curve. Values are the mean ± standard error of the mean. ACTH time effect P < 0.0001; group–time interaction P < 0.0001. Cortisol time effect P < 0.0001; group–time interaction P < 0.0001. ACTH AUC time effect P = 0.03; group–time interaction P = 0.03. Cortisol AUC group effect P = 0.007; time effect P = 0.02; group–time interaction P = 0.0005. Singleton bearing (S; N, n = 8; UN, n = 5) and multiple bearing (M; N, n = 5; UN, n = 7) ewes shown at 29 and 49 days of gestation. There are no significant differences between S and M ewes in baseline ACTH, cortisol, ACTH AUC or cortisol AUC.

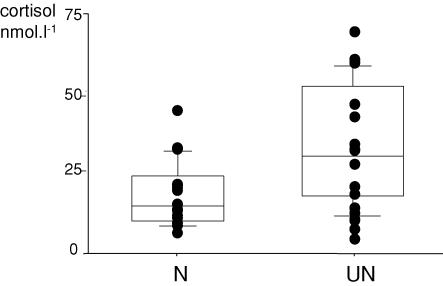

At the start of the experiment (day −61), mean plasma concentrations of both ACTH and cortisol were higher in the UN group (Table 2). This was due to five ewes with high levels in this group (Fig. 2). In all subsequent samples, plasma cortisol concentrations in these initial outliers were not different from the rest of the UN group.

Figure 2. Plasma cortisol concentrations in well nourished (N) and undernourished (UN) animals at the start of the experiment on day −61.

Points represent individual sheep. Horizontal lines represent 10th, 25th, 50th 75th and 90th percentiles. P = 0.017 for difference between UN and N groups.

Cortisol and ACTH findings

In the N ewes, baseline plasma concentrations of ACTH and cortisol did not change significantly during the experiment. In the UN ewes, concentrations of both ACTH and cortisol decreased during the experiment (time effect ACTH P < 0.0001, cortisol P < 0.0001) and were significantly lower than in N ewes from mating until after refeeding. Mean cortisol concentration increased after refeeding but was still significantly lower in UN than N ewes at the end of the experiment (group–time interaction P < 0.0001, Table 2).

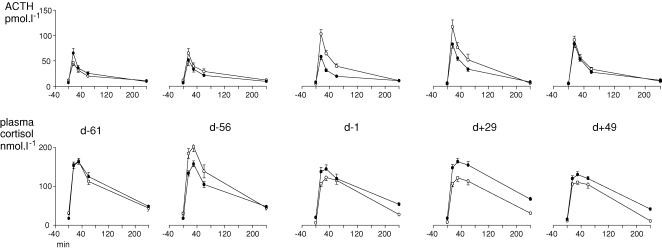

At −61 days gestation, prior to nutritional manipulation, ACTH and cortisol AUC in response to AVP–CRH were not different between groups. In the N group, there was no change in either ACTH or cortisol response during the experiment.

ACTH AUC increased in the UN group from the time of mating until refeeding (time effect P = 0.0003, group–time interaction P = 0.03), decreasing thereafter to be not different from the N group at +50 days (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. ACTH and cortisol responses to AVP–CRH challenge.

Filled circles represent well nourished (N) group, open circles represent undernourished (UN) group, See text for statistical details.

The cortisol (but not ACTH) response increased in the UN group immediately after the 2-day fast but then decreased progressively over time (time effect P = 0.0003; group–time interaction P = 0.0002). Cortisol AUC was lower in UN than N ewes from the time of mating until the end of the experiment at +50 days (Fig. 3).

Mean fetal plasma cortisol concentrations at postmortem were not different between nutritional groups (N 46 ± 6 nmol l−1, n = 17; UN 40 ± 4 nmol l−1, n = 15).

Adrenal and placental findings

Maternal adrenal mRNA levels of ACTH-R, StAR and P450c17 were all down-regulated in the pregnant UN ewes at 50 days gestation (ratios of target gene to reference gene (18S) relative to values in N group (95% confidence intervals) ACTH-R 0.82 (0.79–0.86), StAR 0.55 (0.50–0.61), P450c17 0.83 (0.78–0.88)).

Placental 11βHSD2 activity was decreased in the undernourished ewes at 50 days gestation, with cortisol cortisone conversion rate 1.60 ± 0.21 pmol mg−1 min−1 in N ewes and 0.89 ± 0.15 pmol mg−1 min−1 in UN ewes (P = 0.014).

Discussion

We hypothesized that maternal undernutrition could result in exposure of the embryo/fetus to excess glucocorticoid if baseline cortisol concentrations were increased, if the response to AVP–CRH stimulation was exaggerated, or if regulation of placental transfer of cortisol was altered. However our results refute that hypothesis; rather, prolonged periconceptional undernutrition in sheep suppressed basal concentrations of both ACTH and cortisol in maternal plasma. Acute starvation produced a transiently increased cortisol response to AVP–CRH. However, ongoing moderate undernutrition resulted in a decreased cortisol response to AVP–CRH despite increased ACTH response and down-regulation of adrenal ACTH receptor, StAR and P450c17. Placental 11βHSD2 activity was reduced at 50 days gestation, and fetal cortisol concentrations were not different between nutritional groups at this time. These data refute the suggestion that exposure of the embryo/fetus to excess maternal glucocorticoids during the period of undernutrition is likely to explain the effects of periconceptional undernutrition on subsequent fetal growth and maturation. However, we speculate that such exposure may be possible later in gestation, if 11βHSD2 remains low after the maternal cortisol concentration has returned to normal.

There has been a widespread assumption that undernutrition is a physiological ‘stressor’ that always results in elevation of stress hormones including glucocorticoids. This is supported by clinical findings of high basal cortisol level and loss of circadian cortisol cycling in anorexia nervosa (Douyon & Schteingart, 2002), studies of human malnutrition showing improved nutrition resulted in normalization of elevated plasma cortisol concentration (Malozowski et al. 1990), and animal studies of acute starvation, in which glucocorticoid concentration is increased in a variety of species (Stewart et al. 1988). However, animal experiments looking at the effect of more prolonged, less severe undernutrition have yielded less consistent results. In non-pregnant rats food deprivation for 60 h elevated basal levels of corticosterone but not ACTH (Kiss et al. 1994). Pregnant rats undernourished in late gestation (50% food restriction) also had increased plasma corticosterone levels at term (Lesage et al. 2002). Undernutrition in late gestation ewes resulted in a rise in maternal cortisol concentration for the first 10 days; however, when the period of undernutrition was increased to 20 days, cortisol levels returned to normal, suggesting that duration of undernutrition may be an important factor (Edwards & McMillen, 2001). Intriguingly, in another study HPA axis function of the adult offspring was also affected by maternal undernutrition for 10 but not 20 days in late gestation (Bloomfield et al. 2003a). Furthermore, sheep undernourished for prolonged periods in the periconceptional period and in early to mid gestation have reduced maternal glucocorticoid concentrations (Bispham et al. 2003; Bloomfield et al. 2004). These findings suggest that nutritional effects on HPA axis regulation may vary between species, and are affected by the duration and severity of undernutrition.

Furthermore, fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoid after maternal undernutrition has not been specifically assessed. Our study showed no difference in fetal plasma cortisol concentrations between nutritional groups at 50 days, although these results are more likely to reflect cortisol response to stress rather than basal levels because they were collected at postmortem. The offspring of rats undernourished in late gestation had decreased placental 11βHSD2 expression, high plasma corticosterone levels at birth, decreased growth and altered HPA axis function (Lesage et al. 2001). However, adrenalectomy and corticosterone replacement moderated the effects of maternal undernutrition on placental 11βHSD2 expression suggesting a possible relationship between expression of this enzyme and circulating glucocorticoid levels (Lesage et al. 2002). Offspring of adrenalectomised mothers were small but showed normal HPA axis development, suggesting that alteration of placental glucocorticoid transfer without elevated maternal plasma glucocorticoid levels has a lesser effect on fetal development in the rat.

In this study, undernutrition was commenced 2 months before mating to ensure that any acute effects of fasting on maternal plasma cortisol concentrations could not directly influence the embryo, and to ensure that a stable plane of nutrition was achieved by the time of mating. Brief exposure of fetal sheep to exogenous glucocorticoid between 26 and 28 days of gestation has been shown to result in postnatal hypertension, possibly via altered nephrogenesis and angiotensin regulation (Dodic et al. 2002). We were concerned that refeeding the undernourished ewes at a similar time in gestation in this experiment might reproduce this effect by causing a transient rise in maternal cortisol concentrations. However we found no acute rise in maternal cortisol concentrations after refeeding at 30 days of gestation. Rather, cortisol concentrations gradually returned to levels similar to those of the well nourished controls, and ACTH response to AVP–CRH reverted to baseline values. Although we may not have detected a very brief rise in cortisol concentrations, our findings suggest that elevated maternal baseline plasma cortisol concentrations are unlikely to mediate the effects of periconceptional undernutrition.

Increased responsiveness of the pituitary to AVP–CRH, or of the adrenal to ACTH, could also result in intermittent high peak concentrations of cortisol which could potentially affect the developing fetus. There are limited data regarding the effect of undernutrition on HPA axis responsiveness. A study in non-pregnant rats restricted food intake to 50% of ad libitum levels for 4 weeks and found reduced response to CRF; however, the underlying mechanism was unclear (Garcia-Belenguer et al. 1993). Our data show that the initial acute decrease in nutrition produced a transient elevation of the glucocorticoid response to ACTH stimulation, but there was adaptation over time to the new plane of nutrition and no evidence of ongoing hyperresponsiveness of the HPA axis.

The increased ACTH response, but decreased cortisol response, to AVP–CRH seen after more prolonged undernutrition suggests the development of adrenal resistance to ACTH, together with reduced negative feedback from cortisol on the pituitary. Resistance to ACTH could be mediated by a decrease in receptor number, or at any point along the postreceptor signalling pathway. In this experiment, there was reduced expression of message for ACTH receptor, the key transcription factor (StAR), and the key regulatory enzyme in cortisol production (P450c17) in the undernourished ewes. The fact that the adrenal changes were still present 20 days after refeeding suggests the nutritional insult may have long-term effects on maternal adrenal function.

It was also possible that periconceptional undernutrition could affect the activity of enzymes involved in placental regulation of glucocorticoid transfer. In rats, a low protein diet throughout pregnancy decreased placental 11βHSD2 activity, potentially allowing increased exposure of the fetuses to maternal corticosterone (Langley-Evans et al. 1996). In sheep nutritionally restricted from 28 to 77 days gestation, placental 11βHSD2 was also reduced in mid-gestation (Whorwood et al. 2001). In our study, placental 11βHSD2 activity was decreased in the undernourished ewes at 50 days gestation, 20 days after refeeding. At this time, plasma cortisol concentrations and cortisol response to AVP–CRH stimulation were still reduced compared to controls. It is therefore possible that, if maternal plasma cortisol levels subsequently returned to normal while 11βHSD2 activity was still low, the fetus could be exposed to excess maternal cortisol in mid-gestation. This raises the interesting possibility that the effects of undernutrition in the periconceptional period could be mediated in part via fetal exposure to excess maternal glucocorticoids in mid-gestation. We are currently exploring this possibility in more detail.

Mean plasma concentrations of ACTH and cortisol at the start of the experiment were higher in the UN group, with 5 of the 21 ewes having significantly higher cortisol concentrations than the rest of the group. This is unexplained, but Roussel et al. (2003) describe high and low glucocorticoid ‘responders’ to stress, with some animals having an exaggerated initial glucocorticoid response that ‘normalises’ with repeated exposure to the same stimulus. It may be that some animals in our experiment were slower to adjust to handling and the new environment than others, despite the 10 day acclimatization period. By day −29, these five ewes were no longer different from the rest of the group. All animals in the UN group had a decrease in plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations during the period of undernutrition regardless of their initial levels; therefore the results are not explained by the change in cortisol concentrations only in the subset of ewes with a high initial plasma cortisol.

One limitation of the cortisol assay we used is the inability to distinguish between free plasma cortisol and that bound to circulating corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG). It is therefore possible that the measured fall in baseline cortisol concentration may not reflect a true decrease in free (or active) hormone, but rather a fall in CBG with no change or even an increase in free cortisol. However, the total cortisol levels in the UN group were extremely low, remaining at less than one-third of that of the N group throughout the period from the time of mating to refeeding. Thus CBG levels would have to have fallen more than threefold to prevent a decrease in free cortisol levels in the UN group. Furthermore, in our previous study using a similar undernutrition protocol, free cortisol concentrations were measured on three occasions during the period of undernutrition and were significantly lower in the undernourished group (Bloomfield et al. 2004). Thus changes in CBG levels seem most unlikely to explain our findings.

It is also unlikely that the UN ewes experienced altered circadian rhythms of cortisol secretion such that 24 h cortisol secretion may be elevated despite consistently lower basal plasma cortisol concentrations. Previous studies show that once-daily feeding in sheep results in diurnal variation of cortisol, with peak plasma concentrations of cortisol at the time of the feed (Simonetta et al. 1991). In our experiment, ewes were established on once-daily feeding in the morning 10 days before entry to the study, a pattern which was continued throughout the experiment. Diurnal data obtained at days −29 and +49 in the 10 unmated sheep showed development of diurnal variation of maternal cortisol concentrations associated with the time of the feed by the end of the experiment, but there was no difference in timing or magnitude of peak cortisol concentrations between nutritional groups (data not shown).

We have previously shown that fetal lambs whose mothers were undernourished in the periconceptional period had accelerated maturation of their HPA axis, resulting in shortened gestation length (Bloomfield et al. 2003). Our data suggest that these fetuses may have been exposed to an environment of markedly reduced rather than excess maternal glucocorticoids throughout at least the first third of gestation. This may itself affect fetal development (Langley-Evans, 1997b). Adrenalectomy of pregnant rats has been reported to result in increased fetal secretion of corticosterone, with low birth weight and altered postnatal thyroid function in the offspring (Chatelain et al. 1980). It is therefore possible that the accelerated HPA maturation seen after periconceptional undernutrition (Bloomfield et al. 2004) could be an adaptation to low maternal glucocorticoid activity; this requires further investigation.

In summary, prolonged periconceptional undernutrition in sheep depressed basal maternal ACTH and cortisol concentrations, reduced cortisol, but not ACTH, response to AVP–CRH stimulation, and induced adrenal resistance to ACTH. It is therefore unlikely that the fetal effects of periconceptional undernutrition are mediated directly by exposure of the developing embryo/fetus to excess maternal glucocorticoid in the periconceptional period. Rather, accelerated maturation of the fetal HPA axis may reflect intrauterine adaptation to a low glucocorticoid environment. Furthermore, placental 11βHSD2 activity was still decreased 20 days after refeeding, potentially allowing increased fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids later in gestation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Pierre Van Zijl and Mhoyra Fraser, Janine Street and Davanea Forbes to the assay work, Hui-Hui Phua to the molecular analyses and Chris McMahon, Selwyn Stuart, John Lange and Trevor Watson to the animal work. This study was supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand and the Canadian Institute of Health Research. A.L.J. was supported by a Senior Health Research Scholarship from the University of Auckland.

References

- Benediktsson R, Lindsay RS, Noble J, Seckl JR, Edwards CR. Glucocorticoid exposure in utero: new model for adult hypertension. Lancet. 1993;341:339–341. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bispham J, Gopalakrishnan GS, Dandrea J, Wilson V, Budge H, Keisler DH, Broughton Pipkin F, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Maternal endocrine adaptation throughout pregnancy to nutritional manipulation: consequences for maternal plasma leptin and cortisol and the programming of fetal adipose tissue development. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3575–3585. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Giannoulias CD, Gluckman PD, Harding JE, Challis JR. Brief undernutrition in late-gestation sheep programs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in adult offspring. Endocrinology. 2003a;144:2933–2940. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Hawkins P, Campbell M, Phillips DJ, Gluckman PD, Challis JR, Harding JE. A periconceptional nutritional origin for noninfectious preterm birth. Science. 2003b;300:606. doi: 10.1126/science.1080803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield FH, Oliver MH, Hawkins P, Holloway AC, Campbell M, Gluckman PD, Harding JE, Challis JR. Periconceptional undernutrition in sheep accelerates maturation of the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in late gestation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4278–4285. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks AN, Challis JR. Effects of CRF, AVP and opioid peptides on pituitary-adrenal responses in sheep. Peptides. 1989;10:1291–1293. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(89)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelain A, Dupouy JP, Allaume P. Fetal-maternal adrenocorticotropin and corticosterone relationships in the rat: effects of maternal adrenalectomy. Endocrinology. 1980;106:1297–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodic M, May CN, Wintour EM, Coghlan JP. An early prenatal exposure to excess glucocorticoid leads to hypertensive offspring in sheep. Clin Sci. 1998;94:149–155. doi: 10.1042/cs0940149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodic M, Moritz K, Koukoulas I, Wintour EM. Programmed hypertension: kidney, brain or both? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(02)00693-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douyon L, Schteingart DE. Effect of obesity and starvation on thyroid hormone, growth hormone, and cortisol secretion. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(01)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LJ, McMillen IC. Maternal undernutrition increases arterial blood pressure in the sheep fetus during late gestation. J Physiol. 2001;533:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0561a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Belenguer S, Oliver C, Mormede PJ. Facilitation and feedback in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis during food restriction in rats. Neuroendocrinol. 1993;5:663–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1993.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DS, Jackson AA, Langley-Evans SC. The effect of prenatal diet and glucocorticoids on growth and systolic blood pressure in the rat. Proc Nutri Soc. 1998;57:235–240. doi: 10.1079/pns19980037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JE. The nutritional basis of the fetal origins of adult disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:15–23. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami M, Jobe AH, Newnham J, Polk DH, Willet KE, Sly P. Repetitive prenatal glucocorticoids improve lung function and decrease growth in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:178–184. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.1.9612036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffray TM, Matthews SG, Hammond GL, Challis JR. Divergent changes in plasma ACTH and pituitary POMC mRNA after cortisol administration to late-gestation ovine fetus. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E417–E425. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.3.E417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe AH, Wada N, Berry LM, Ikegami M, Ervin MG. Single and repetitive maternal glucocorticoid exposures reduce fetal growth in sheep. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;178:880–885. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70518-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss A, Jezova D, Aguilera G. Activity of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis and sympathoadrenal system during food and water deprivation in the rat. Brain Res. 1994;663:84–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC. Hypertension induced by foetal exposure to a maternal low-protein diet, in the rat, is prevented by pharmacological blockade of maternal glucocorticoid synthesis. J Hypertens. 1997a;15:537–544. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715050-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC. Intrauterine programming of hypertension by glucocorticoids. Life Sci. 1997b;60:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00611-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Benediktsson R, Gardner DS, Edwards CR, Jackson AA, Seckl JR. Protein intake in pregnancy, placental glucocorticoid metabolism and the programming of hypertension in the rat. Placenta. 1996;17:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(96)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Blondeau B, Grino M, Breant B, Dupouy JP. Maternal undernutrition during late gestation induces fetal overexposure to glucocorticoids and intrauterine growth retardation, and disturbs the hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal axis in the newborn rat. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1692–1702. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage J, Hahn D, Leonhardt M, Blondeau B, Breant B, Dupouy JP. Maternal undernutrition during late gestation-induced intrauterine growth restriction in the rat is associated with impaired placental GLUT3 expression, but does not correlate with endogenous corticosterone levels. J Endocrinol. 2002;174:37–43. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1740037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RS, Lindsay RM, Waddell BJ, Seckl JR. Prenatal glucocorticoid exposure leads to offspring hyperglycaemia in the rat: studies with the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor carbenoxolone. Diabetologia. 1996;39:1299–1305. doi: 10.1007/s001250050573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malozowski S, Muzzo S, Burrows R, Leiva L, Loriaux L, Chrousos G, Winterer J, Cassorla F. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in infantile malnutrition. Clin Endocrinol. 1990;32:461–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1990.tb00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Osgerby JC, Thurston LM, Gadd TS, Wood PJ, Wathes DC, Michael AE. Alterations in placental 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11βHSD) activities and fetal cortisol:cortisone ratios induced by nutritional restriction prior to conception and at defined stages of gestation in ewes. Reproduction. 2004;127:717–725. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyirenda MJ, Lindsay RS, Kenyon CJ, Burchell A, Seckl JR. Glucocorticoid exposure in late gestation permanently programs rat hepatic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucocorticoid receptor expression and causes glucose intolerance in adult offspring. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2174–2181. doi: 10.1172/JCI1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyirenda MJ, Welberg LA, Seckl JR. Programming hyperglycaemia in the rat through prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids-fetal effect or maternal influence? J Endocrinol. 2001;170:653–660. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1700653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MH, Hawkins P, Breier BH, Van Zijl PL, Sargison SA, Harding JE. Maternal undernutrition during the periconceptual period increases plasma taurine levels and insulin response to glucose but not arginine in the late gestational fetal sheep. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4576–4579. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver MH, Hawkins P, Harding JE. Periconceptional undernutrition alters growth trajectory and metabolic and endocrine responses to fasting in late-gestation fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:591–598. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000155942.18096.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel S, Hemsworth P, Boissy A, Duvaux-Ponter C. Effects of repeated stress during pregnancy in ewes on the behavioural and physiological responses to stressful events and birth weight of their offspring. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2003;85:259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Simonetta G, Walker DW, McMillen IC. Effect of feeding on the diurnal rhythm of plasma cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone concentrations in the pregnant ewe and sheep fetus. Exp Physiol. 1991;76:219–229. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda DM, Newnham JP, Challis JR. Effects of repeated maternal betamethasone administration on growth and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function of the ovine fetus at term. J Endocrinol. 2000;165:79–91. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloboda DM, Newnham JP, Challis JR. Repeated maternal glucocorticoid administration and the developing liver in fetal sheep. Endocrinol. 2002;175:535–543. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1750535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J, Meaney MJ, Aitken D, Jensen L, Kalant N. The effects of acute and life-long food restriction on basal and stress-induced serum corticosterone levels in young and aged rats. Endocrinology. 1988;123:1934–1941. doi: 10.1210/endo-123-4-1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welberg LA, Seckl JR, Holmes MC. Inhibition of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, the foeto-placental barrier to maternal glucocorticoids, permanently programs amygdala GR mRNA expression and anxiety-like behaviour in the offspring. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1047–1054. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whorwood CB, Firth KM, Budge H, Symonds ME. Maternal undernutrition during early to midgestation programs tissue-specific alterations in the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoforms, and type 1 angiotensin II receptor in neonatal sheep. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2854–2864. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.7.8264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K, Berdusco ET, Challis JR. Opposite effects of glucocorticoid on hepatic 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase mRNA and activity in fetal and adult sheep. J Endocrinol. 1994;143:121–126. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1430121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]