Abstract

Activity-dependent long-term synaptic changes were investigated at glutamatergic synapses in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) of the rat hypothalamus. In acute hypothalamic slices, high frequency stimulation (HFS) of afferent fibres caused long-term potentiation (LTP) of the amplitude of AMPA receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) recorded with the whole-cell patch-clamp technique. LTP was also obtained in response to membrane depolarization paired with mild afferent stimulation. On the other hand, stimulating the inputs at 5 Hz for 3 min at resting membrane potential caused long-term depression (LTD) of excitatory transmission in the SON. These forms of synaptic plasticity required the activation of NMDA receptors since they were abolished in the presence of d-AP5 or ifenprodil, two selective blockers of these receptors. Analysis of paired-pulse facilitation and trial-to-trial variability indicated that LTP and LTD were not associated with changes in the probability of transmitter release, thereby suggesting that the locus of expression of these phenomena was postsynaptic. Using sharp microelectrode recordings in a hypothalamic explant preparation, we found that HFS also generates LTP at functionally defined glutamatergic synapses formed between the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis and SON neurons. Taken together, our findings indicate that glutamatergic synapses in the SON exhibit activity-dependent long-term synaptic changes similar to those prevailing in other brain areas. Such forms of plasticity could play an important role in the context of physiological responses, like dehydration or lactation, where the activity of presynaptic glutamatergic neurons is strongly increased.

The supraoptic nucleus (SON), which is part of the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system, consists of magnocellular neurons that synthesize either vasopressin (VP) or oxytocin (OT). These neurons project their axons into the neurohypophysis where OT and VP are secreted directly into the blood stream. VP plays a key role in body fluid and cardiovascular regulation whereas OT is involved primarily in reproductive functions, such as lactation and parturition. The release of these two neurohormones is controlled directly by the electrical activity of their parent neurons (Poulain & Wakerley, 1982), which itself is influenced by excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs. Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the SON (Wuarin & Dudek, 1993). Indeed, glutamatergic inputs to the SON have been shown to originate both from intra- and extrahypothalamic areas such as the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis (OVLT), the subfornical organ, the median preoptic nucleus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the amygdala complex and the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Csaki et al. 2002).

Previous studies have shown that glutamatergic inputs play an important role in the regulation of SON neuron excitability (Gribkoff & Dudek, 1988, 1990; Parker & Crowley, 1993a,b; Wuarin & Dudek, 1993) and in many instances this role is functionally defined. For example, presynaptic activity in the OVLT-SON pathway is modulated in a manner that increases the frequency of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and action potential firing rate in SON neurons in proportion with fluid osmolality (Richard & Bourque, 1995). Similarly, the brief (2–4 s) and high frequency (40–80 Hz) bursts of action potentials displayed by OT neurons prior to milk ejection are thought to result from afferent volleys of glutamatergic EPSPs (Jourdain et al. 1998). The actions of glutamate in the SON are mediated through ionotropic AMPA and NMDA receptors (AMPARs and NMDARs), as well as by metabotropic glutamate receptors (Wuarin & Dudek, 1993; Schrader & Tasker, 1997; Stern et al. 1999). In particular, AMPARs and NMDARs are activated during fast excitatory transmission in the SON, and inward current flowing through AMPARs mediates most of the EPSPs observed at the normal resting potential of VP and OT neurons (Wuarin & Dudek, 1993; Stern et al. 1999). NMDARs are also involved in other cellular processes associated with their Ca2+ permeability, including regenerative voltage oscillations (Hu & Bourque, 1992) and somatodendritic hormone release (De Kock et al. 2004). Moreover, blocking NMDARs inhibits phasic activity in VP neurons and attenuates the bursting behaviour of OT cells during the milk ejection reflex (Nissen et al. 1994; Moos et al. 1997).

Studies in other brain regions have shown that NMDARs can play a critical role in the induction of long-term synaptic changes such as long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) (for a review see in Malenka & Nicoll, 1999; Malenka & Bear, 2004). These forms of activity-dependent plasticity, respectively, mediate persistent increases and decreases in AMPAR-dependent EPSPs and can therefore alter the relative weight of affected synapses compared to others. In brain areas such as the hippocampus such effects contribute to associative learning and memory (Lynch, 2004). Whether activity-dependent plasticity occurs at excitatory synapses on SON neurons is unknown. In this study therefore we examined if glutamatergic afferents to SON neurons can express different forms of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity, whether NMDAR play a role in such phenomena, and if activity-dependent LTP can be induced in a functionally defined pathway.

Methods

Preparation of acute slices and hypothalamic explants

Acute hypothalamic slices were obtained using procedures similar to those previously described (Oliet & Poulain, 1999). Briefly, Wistar female rats (1–2 months old) were anaesthetized with isofluorane (100% O2 and 5% isoflurane for 1 min) and decapitated. The brain was quickly removed and placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Thin coronal slices (300 μm) were cut with a vibratome (Leica) from a block of tissue containing the hypothalamus. Slices including the SON were hemisected along the midline and allowed to recover for at least 1 h before recording. A slice was then transferred into a recording chamber where it was submerged and continuously perfused (1–2 ml min−1) with ACSF at room temperature. The composition of the ACSF was (mm): 123 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 Na2HPO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 1.3 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2 and 10 glucose (pH 7.4; 295–300 mosmol kg−1).

Hypothalamic explants were prepared as previously described (Ghamari-Langroudi & Bourque, 1998). Briefly, Long-Evans male rats were killed by decapitation and the brain rapidly removed. A block of tissue containing the basal hypothalamus was excised using razor blades and pinned to the slanted Sylgard base of a recording chamber. Explants were superfused (0.5–1 ml min−1) with carbogenated (95% O2 and 5% CO2), warmed (31–32°C) ACSF containing (mm): 121 NaCl, 3 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.3 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2 and 10 glucose (pH 7.4; 295–300 mosmol kg−1).

Patch-clamp and intracellular recordings

Magnocellular neurons in hypothalamic slices were visually identified using infrared differential interference contrast microscopy (Olympus BX50WI microscope). Patch-clamp recording pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass (1.2 mm o.d., 0.6 mm i.d., Clark Electromedical) and filled with an internal solution containing (mm): 120 potassium gluconate, 1.3 MgCl2, 1 EGTA, 10 Hepes and 0.1 CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.1 with KOH; 295–300 mosmol kg−1). For experiments involving a pairing protocol, the internal solution contained (mm): 130 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 1 EGTA, 5 QX-314 chloride and 0.1 CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.1 with CsOH; 295–300 mosmol kg−1). Signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 5 kHz via a DigiData 1200 or 1300 interface (Axon Instruments, Inc., Union City, CA, USA). Series resistance (6–20 MΩ) was monitored online and cells were excluded from data analysis if more than a 15% change occurred during the course of the experiment. Membrane currents were recorded in voltage clamp mode using either an Axopatch-1D or a Multiclamp 700A amplifier (Axon Instruments) and analysed on-line using pCLAMP 9 (Axon Instruments). Data, reported as means ± s.e.m., were compared statistically with paired or unpaired Student's t test. Significance was assessed at P < 0.05. Excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were evoked at 0.066 Hz through a stimulating glass electrode filled with ACSF and placed in the area dorsal to the SON (Kombian et al. 1996). The amplitude of the EPSCs was measured by calculating the average of a 2–3 ms windows around the peak of the EPSC relative to baseline. The data were normalized to the average value obtained during the 10–15 min period prior to applying the LTP or LTD inducing stimulus.

Intracellular recordings were obtained using sharp micopipettes prepared from 1.2 mm o.d. glass capillary tubes (A-M Systems Inc, Carlsborg, WA, USA) pulled on a P87 Flaming-Brown puller (Sutter Instrument Co., Novato, CA, USA). Pipettes were filled with 2 m potassium acetate, yielding a DC resistance of 70–150 MΩ. Recordings of membrane voltage were obtained though an Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Axon Instruments). Voltage recordings were performed in continuous current clamp mode. Electrical stimulation of the OVLT was performed via a bipolar electrode constructed from a pair of nichrome wires (62 μm o.d.) separated by ∼0.3 mm.

Pairing-induced LTP was obtained by pairing membrane depolarization (0 mV) with synaptic stimulation at 2 Hz for 45 s. High frequency stimulation (HFS)-induced LTP was obtained by using a 100 Hz train of stimuli for 1 s in current clamp mode (I = 0), repeated 4 times at 15 s intervals. The LTD-induction protocol was a 5 Hz/3 min train of stimuli given in current clamp mode (I = 0).

The paired-pulse facilitation ratio was calculated as the amplitude ratio of the second EPSC over the first EPSC elicited 50 ms later. The coefficient of variation (CV) of EPSCs was calculated as CV = s.d./mean. Data were compared statistically using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test or the parametric paired t test accordingly. Significance was assessed at P < 0.05. All data are reported as means ± s.e.m.

Drugs

All drugs were bath-applied. Appropriate stock solutions were made and diluted with ACSF immediately before application. QX-314 chloride (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) was diluted directly in the patch-solution. Drugs used were 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA; Sigma), d(−)-2-amino-5-phosphono-pentanoic acid (d-AP5), ifenprodil hemitartrate and bicuculline methobromide (Tocris).

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the European Animal Care Guidelines and Directives. The tissue harvesting protocol for hypothalamic explants was approved by the McGill University Animal Care Committee.

Results

Properties of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses in the SON

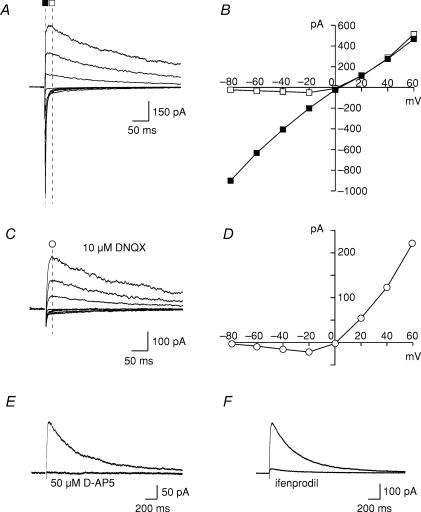

We first tested whether synaptic NMDARs were activated in response to focal afferent stimulation of glutamatergic inputs in acute hypothalamic slices. In the presence of bicuculline (20 μm) to inhibit GABAA receptors, stimulation of the area dorsal to the SON evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) that reversed near 0 mV (Fig. 1). At negative potentials, these EPSCs had fast kinetics whereas they were very slow at positive voltage (Fig. 1A). The current–voltage (I–V) relationship measured 5 ms after the stimulation was linear whereas it was inwardly rectifying when the current amplitude was measured 40 ms later (Fig. 1B). Under conditions where AMPARs were inhibited with a specific antagonist, DNQX (10 μm), the I–V curve was no longer linear but presented a rectification typical of the voltage-dependent Mg2+ inhibition of NMDARs (Fig. 1C and D) (Mayer et al. 1984). This was confirmed by the complete inhibition of the response by a specific NMDAR antagonist, d-AP5 (50 μm; Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Properties of synaptic NMDAR-mediated responses.

A, evoked EPSCs obtained from a representative SON neuron at different membrane potentials (from −80 to +60 mV). Traces are averages of 5–10 consecutive sweeps. B, current–voltage (I–V) relationships obtained from the traces in A, 5 ms (▪) and 40 ms (□) after stimulation. Note the rectification when the current was measured later on the trace. C and D, evoked EPSCs and corresponding I–V curve obtained in the presence of DNQX. Traces are averages of 5–10 consecutive sweeps. E and F, representative examples of the inhibitory effects of 50 μm D-AP5 and 10 μm ifenprodil on evoked EPSCs recorded in the presence of DNQX. Traces are averages of 5–10 consecutive sweeps.

To determine the subunit composition of the synaptic NMDARs in the SON, we applied ifenprodil, a NMDAR antagonist for NR2B-containing receptors when used at low concentration (Williams, 1993). As illustrated in Fig. 1F, 10 μm ifenprodil reduced NMDA-EPSC amplitude dramatically (82.8 ± 3.8%; n = 5) indicating that most synaptic NMDARs in this nucleus contained the NR2B subunit.

LTP of glutamatergic transmission in the SON

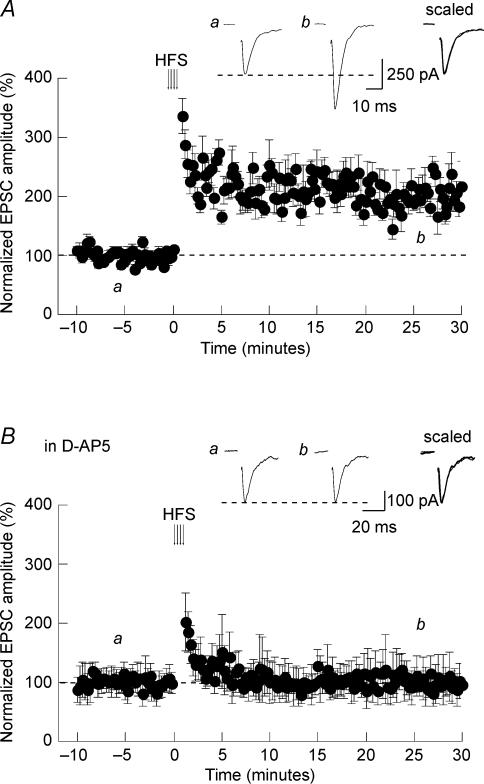

LTP experiments began by acquiring a control baseline of 10 min duration during which glutamatergic afferent inputs were stimulated at low frequency (0.066 Hz) to evoke AMPAR-mediated EPSCs. This frequency did not produce any time-dependent drift in the amplitude of evoked EPSCs. Because NMDAR-dependent forms of LTP are impaired by prolonged intracellular dialysis by the patch pipette solution (Malinow & Tsien, 1990), we induced LTP within 15 min after gaining whole-cell access. We first attempted to potentiate glutamatergic transmission by applying repetitive tetanic stimulations. As show in Fig. 2A, high frequency stimulation (HFS; 4 × 100 Hz − 1 s) of glutamatergic inputs produced a persistent increase of evoked EPSC amplitude. This potentiation lasted as long as the recording remained stable and averaged 194 ± 27% of control responses 30 min after the induction (n = 12; P < 0.05). The kinetics of the EPSCs remained unaffected after the tetanic stimulation. To test for the implication of NMDARs in the induction of this LTP, we repeated the protocol in the presence of 50 μm d-AP5. As illustrated in Fig. 2B, tetanus-induced LTP was completely prevented under conditions where NMDARs were blocked. In this set of experiments, the EPSC amplitude measured 30 min after HFS had a mean of 98 ± 26% of control (n = 11; P > 0.05). It thus appears that NMDARs in the SON are activated during tetanic stimulations of glutamatergic afferent inputs leading to long-term enhancement of excitatory transmission.

Figure 2. HFS-induced LTP in the SON.

A, in rat hypothalamic slices, a high frequency stimulation (arrows) induced LTP of evoked EPSCs. The insets are averaged sample records of 10 sweeps taken at the times indicated from a typical experiment. These traces were superimposed and scaled. B, the same HFS protocol did not induced LTP when given in the presence of 50 μmd-AP5.

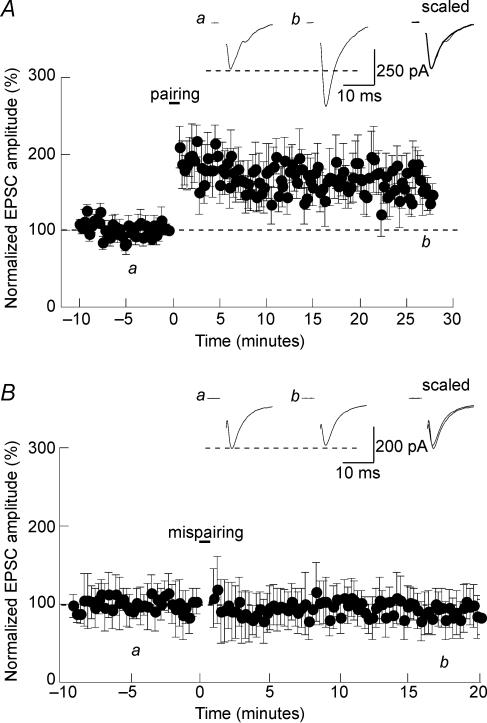

Another classical protocol used to induce LTP during whole-cell patch clamp recording consists in pairing membrane depolarization with afferent synaptic stimulation. Such a pairing protocol was also very efficient at potentiating glutamatergic transmission in the SON. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, pairing afferent stimulation (2 Hz) with membrane depolarization to 0 mV for 45 s caused a long-lasting enhancement of EPSC amplitude (159 ± 23% of control; n = 6; P < 0.05). As a control, the same afferent stimulatory protocol (2 Hz, 45 s) was applied while maintaining the neurons at −60 mV (Fig. 3B). Such ‘mispairing’ protocol did not induce persistent change in EPSC amplitude (87 ± 26%; n = 11; P > 0.05). As it was the case for HFS-induced LTP, pairing-LTP was also entirely blocked by d-AP5 (93 ± 24%; n = 7; P > 0.05; Fig. 4A) indicating that it was mediated by NMDAR activation. To test whether this LTP depended upon the Ca2+ influx associated with NMDA receptor activation, as it is the case for NMDA-dependent LTPs in other brain areas (reviewed in Nicoll, 2003), we included 20 mm BAPTA in the recording patch pipette. As expected, buffering intracellular Ca2+ prevented LTP induction (95 ± 18%; n = 7; P > 0.05; Fig. 4B).

Figure 3. Pairing-induced LTP in the SON.

A, in rat SON neurons, pairing afferent stimulation (2 Hz) with membrane depolarization (0 mV) for 45 s caused LTP of evoked EPSCs. B, stimulating the afferent inputs at 2 Hz without depolarizing the neurons (mispairing) failed to induce LTP.

Figure 4. Involvement of NMDARs in LTP induction in the SON.

A, in the presence of 50 μmd-AP5, pairing afferent stimulation with membrane depolarization failed to induce LTP. B, pairing-LTP was prevented when BAPTA was included in the patch pipette to buffer intracellular Ca2+.

LTD of glutamatergic transmission in the SON

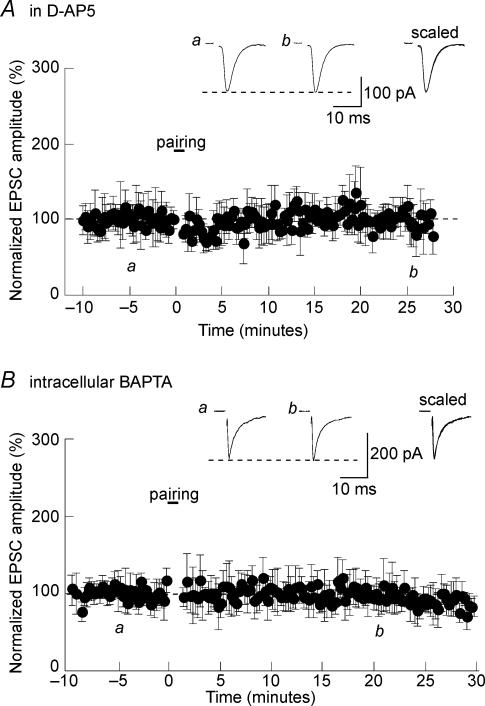

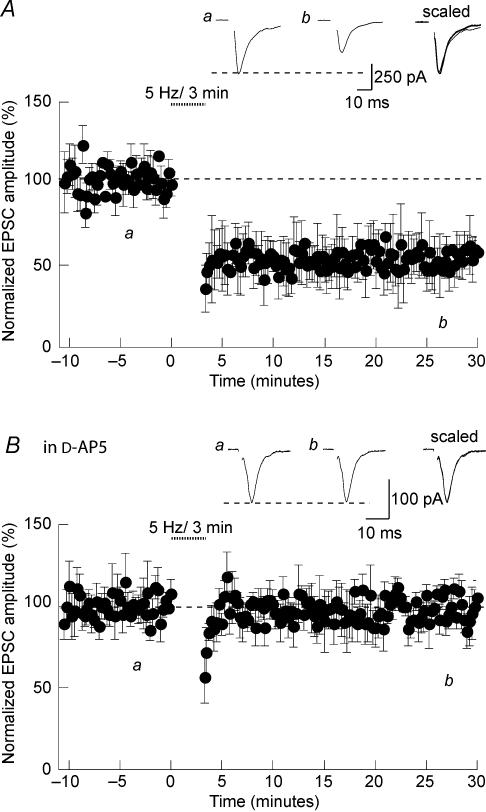

To induce long-term depression (LTD) at glutamatergic synapses in the SON, afferent fibres were stimulated at 5 Hz for 3 min in current clamp mode at resting membrane potential. This protocol caused a pronounced long-lasting reduction of evoked-EPSC amplitude (57 ± 12% of control; n = 11; P < 0.05; Fig. 5A). To determine whether this form of synaptic plasticity depended on NMDAR activation, we repeated these experiments in the presence of d-AP5 in the bathing solution. Under such conditions, the evoked EPSCs were no longer depressed following the induction protocol (98 ± 11% of control; n = 11; P > 0.05), confirming the role of NMDARs in the induction of this LTD (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Induction of NMDAR-LTD in the SON.

A, in rat hypothalamic slices, stimulating the afferent fibres at 5 Hz for 3 min in current clamp mode at resting membrane potential induced LTD of evoked EPSCs. B, the same protocol did not induced LTD when given in the presence of 50 μmd-AP5.

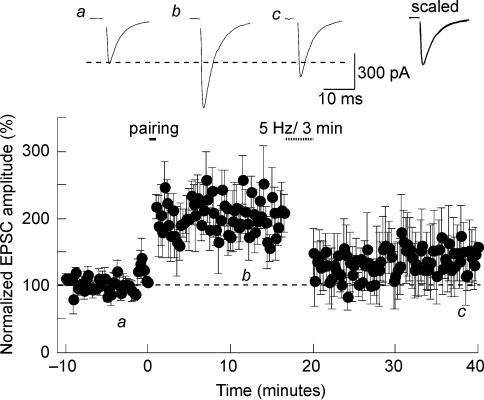

In a limited number of cells (n = 4), we were able to depress synapses that had been potentiated previously (Fig. 6). This phenomenon, also known as depotentiation, indicates that LTP and LTD can be elicited reversibly at the same set of synapses.

Figure 6. Depotentiation in the SON.

Synaptic strength can be sequentially increased and decreased at a single set of synapses. Synapses were first potentiated by a pairing protocol and then depotentiated 15 min later with a 5-Hz-3 min train of stimulation.

Role of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in LTP and LTD

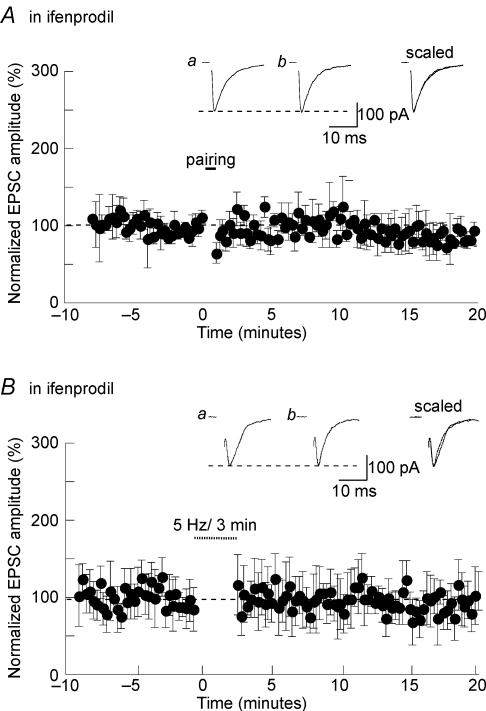

Recent reports have show that specific blockade of NR2B- and NR2A-containing receptors in the hippocampus inhibited LTD and LTP, respectively (Liu et al. 2004). These findings suggested that NMDA receptor subtypes govern the direction of hippocampal plasticity. Because most of the NMDA receptors present at glutamatergic synapses in SON neurons contain NR2B, we tested whether they were required for the induction of both LTP and LTD. As illustrated in Fig. 7A, pairing-induced LTP was not obtained in the presence of 10 μm ifenprodil (95 ± 12%; n = 5; P > 0.05). Similarly, stimulating afferent fibres at 5 Hz for 3 min did not cause LTD in the presence of the antagonist (106 ± 28%; n = 7; P > 0.05; Fig. 7B). It seems therefore that, unlike what has been reported at hippocampal synapses, NR2B-containing receptors are implicated in the induction of LTP and LTD in the SON.

Figure 7. Involvement of NR2B-containing NMDARs in LTP and LTD in the SON.

Pairing-LTP (A) and LTD (B) were prevented when NR2B-containing NMDA receptors were blocked with 10 μm ifenprodil.

Locus of expression of LTP and LTD

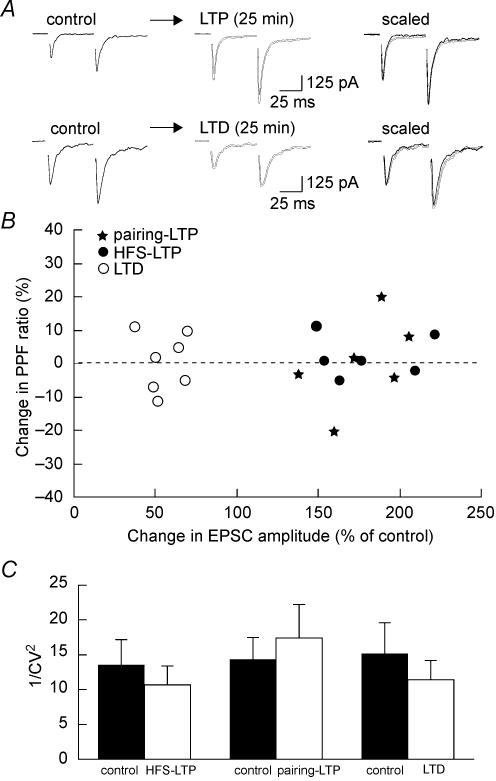

To determine if maintained expression of synaptic plasticity in the SON depends on presynaptic or postsynaptic changes, we examined paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) before and after induction of either LTP or LTD. For these experiments, two stimuli of equal intensity were applied within a very short interval (50 ms). In such a protocol, the amount of facilitation of the second response is inversely correlated to transmitter release probability (Zucker & Regehr, 2002). As illustrated in Fig. 8, PPF was not affected following HFS-induced LTP (n = 6), pairing-induced LTP (n = 7) or LTD (n = 7) of glutamatergic transmission. Moreover, the relative magnitudes of LTP and LTD were not significantly correlated (R = 0.07; P > 0.05) with changes in PPF ratio (Fig. 8B). Another index of changes in presynaptic function is the inverse of the squared coefficient of variation (1/CV2). This parameter that reflects trial-to-trial variation was compared before and after the induction of long-term synaptic changes. As illustrated in Fig. 8C, neither LTP, induced by HFS (n = 10) or pairing (n = 6), nor LTD (n = 11) significantly modified 1/CV2(P > 0.05). Taken together, these findings argue against the involvement of a change in the probability of transmitter release to explain these long-term modifications of synaptic strength and therefore support a postsynaptic locus of expression of LTP and LTD in the SON.

Figure 8. Postsynaptic locus of expression of LTP and LTD in the SON.

A, representative examples where a pair of stimulations was applied at 50 ms interval before (control) and after induction of HFS-LTP (top) and LTD (bottom). Traces, which are averages of 5–10 consecutive sweeps, were superimposed and scaled to the amplitude of the first EPSC obtained under control conditions (right panel). Note that LTP and LTD did not affect the paired-pulse facilitation. B, plot summarizing the change in PPF (y-axis) as a function of the change in EPSC amplitude (x-axis) associated with HFS-LTP (•), pairing LTP (⋆) and LTD (○). C, summary bar graph of 1/CV2 values measured before (filled bars) and after (open bars) the induction of HFS-LTP, pairing LTP and LTD. Note that 1/CV2 was not affected by any of these long-term changes.

LTP of the OVLT-SON pathway

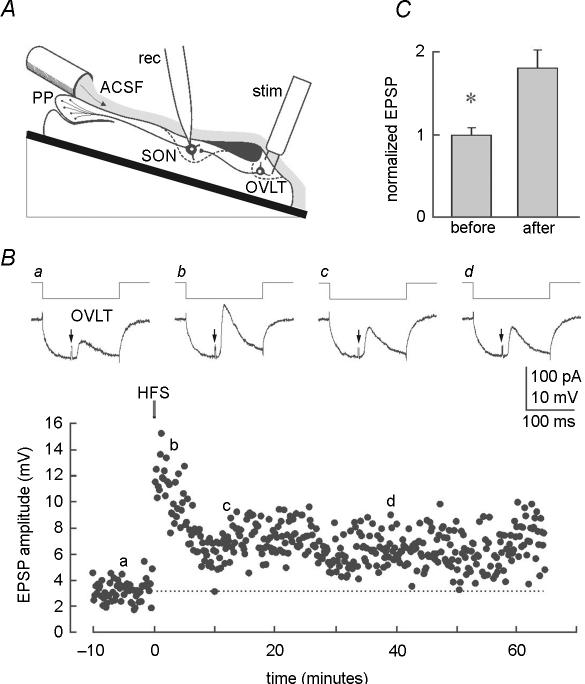

The data presented above indicate that long-lasting activity-dependent changes in synaptic strength can be induced at unidentified glutamatergic inputs activated by focal stimulation near the SON neurons in coronal hypothalamic slices. To determine if a functionally defined glutamatergic projection can also exhibit activity-dependent long-term plasticity, we performed sharp microelectrode recordings from supraoptic neurons in hypothalamic explants to monitor the excitatory input that originates from neurons in the OVLT (Fig. 9A). EPSPs were evoked at a low frequency (0.066 Hz) in the continuous presence of 10 μm bicuculline. Individual EPSPs were evoked during the steady-state phase of the electrotonic response to a hyperpolarizing current pulse injected through the recording electrode to monitor the input resistance of the postsynaptic cell throughout the protocol (Fig. 9B). Small changes in holding current were applied as necessary to maintain the holding potential to a constant value near resting potential. As illustrated in Fig. 9B, HFS of the OVLT caused an immediate enhancement of synaptic transmission that decayed progressively over 5–7 min. Following this period of post-tetanic potentiation (PTP), the amplitude of the EPSP evoked by OVLT stimulation remained typically twice as large as control for the remainder of the recording (Fig. 9C), despite the absence of significant changes in input resistance (e.g. Fig. 9B). Indeed, in seven cells tested in different preparations, the mean amplitude of the EPSP recorded under control conditions was 4.8 ± 0.4 mV, whereas that observed during the maintained phase that followed PTP was 8.5 ± 1.1 mV (P < 0.05). Although these experiments were performed in a different rat strain than that used for slice experiments, we did not observe any relevant differences. We cannot rule out the possibility, however, that slight differences in LTP properties exist between these two strains of animals.

Figure 9. LTP of glutamatergic synapses in the OVLT-SON pathway.

A, schematic diagram providing a side view of the experimental preparation. The tube delivering artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) is positioned just rostral and lateral to the posterior pituitary (PP), while stimulating (stim) and recording (rec) electrodes are placed in the OVLT and SON, respectively. B, representative intracellular recording experiment made in one SON neuron. Upper panels (a–d) show EPSPs evoked in an SON neuron by stimulation of the OVLT (arrows). Each trace is an average of 4 consecutive sweeps taken at various times before and after HFS (see corresponding letters in lower graph). Note that each synaptic response is elicited during the steady-state phase of the electrotonic response to a hyperpolarizing current pulse delivered to monitor input resistance. The lower graph plots the absolute amplitude of EPSPs evoked in the same cell during a representative experiment. Note that input resistance is unaffected while a sustained increase in EPSP amplitude can be observed for more than 1 h following HFS. C, bar graph showing the normalized amplitude of OVLT-mediated EPSPs recorded in 7 SON neurons before and > 30 min following HFS.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to assess whether glutamatergic afferents to SON neurons can exhibit activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. This issue is of importance in view of the crucial role played by glutamatergic inputs in controlling the electrical behaviour, and as a consequence the secretory activity, of vasopressin and oxytocin neurons. Our data indicate that glutamatergic synapses in SON neurons can reversibly undergo NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation and long-term depression.

LTP and LTD at glutamatergic synapses

In the present study, we observed that HFS of glutamatergic inputs to SON neurons causes a long-term enhancement of synaptic strength. A similar potentiation is observed when afferent activity is paired with membrane depolarization. Induction of this LTP was dependent upon NMDAR activation since d-AP5 prevented completely the persistent increase in EPSC amplitude. Analysis of paired-pulse facilitation and of 1/CV2, two indicators of presynaptic function, suggests that LTP expression is not associated with an increase of the probability of transmitter release. LTP in SON neurons therefore is similar to that prevailing in pyramidal neurons of the CA1 region of the hippocampus and which is the best-characterized form of long-term synaptic plasticity in the central nervous system (Nicoll, 2003). It has been clearly established that during HFS or pairing induction protocols, activation of NMDARs leads to a large Ca2+ entry in the dendrites, thereby triggering a cascade of intracellular events resulting in AMPAR insertion at the synapses (Malenka & Nicoll, 1999; Nicoll, 2003). Intacellular Ca2+ buffering with BAPTA prevented LTP in our recordings indicating that a similar cellular mechanism is likely to account for the long-term enhancement of evoked EPSCs observed in the SON. Interestingly, AMPAR insertion was recently described in hypothalamic magnocellular neurons (Gordon et al. 2005), suggesting that such mechanism could underlie LTP expression in SON neurons.

A different form of potentiation of glutamatergic transmission has been reported in SON neurons in response to HFS of local inputs (Kombian et al. 2000). This phenomenon, however, is entirely different from the LTP described here since it is short-lasting (5–15 min), NMDAR-independent, it affects miniature but not evoked EPSCs and is expressed presynaptically. We did notice a transient increased in spontaneous EPSCs following HFS but we believe that it reflected post-tetanic potentiation of the stimulated inputs (Zucker & Regehr, 2002). Nevertheless, we cannot rule out the possibility that short-term potentiation of miniature EPSCs (Kombian et al. 2000) occurs in response to our HFS protocol.

LTD, the opposite phenomenon of LTP, was observed at the same glutamatergic synapses showing LTP in the SON. This persistent reduction was obtained in response to stimulation of the afferents at a frequency of 5 Hz for 3 min while the recorded neurons were in current-clamp mode at resting membrane potential. This induction protocol reliably induces a pronounced LTD in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Oliet et al. 1997). NMDAR activation is required for the induction of LTD in SON neurons, as revealed by the use of d-AP5. PPF and 1/CV2 analyses suggest that LTD expression did not result from a reduction in the probability of transmitter release. It seems therefore that LTD in the SON is similar to the NMDAR-dependent form of LTD observed in the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Oliet et al. 1997). In that region, activation of NMDARs during low frequency stimulation of Schaffer collaterals causes moderate Ca2+ entry in the dendrites, triggering a cascade of intracellular events, distinct from those involved in LTP induction (Malenka & Bear, 2004), and which leads to a removal of AMPARs from the plasma membrane (Luscher et al. 2000).

That a synapse exhibits LTP rather than LTD depends on the extent of Ca2+ entry into the postsynaptic cell upon NMDAR activation. This has been demonstrated in an elegant series of experiments where reducing the number of NMDARs activated during an LTP-induction protocol resulted in long-term depression (Cummings et al. 1996). However, it has been suggested recently that induction of hippocampal LTP and LTD was mediated by the activation of distinct populations of NMDARs (Liu et al. 2004). In this structure, activation of synaptic NMDARs that do not contain the NR2B subunit caused LTP whereas activation of extrasynaptic NMDARs, which contain NR2B, induced LTD. In other terms, it appears that LTP induction protocols such as HFS or pairing are appropriate to stimulate synaptic NMDARs, whereas low frequency stimulation, or other LTD inducing protocols, cause glutamate spillover, thereby activating extrasynaptic NMDARs. Although glutamate spillover and activation of non-synaptic NMDARs could also be involved in the generation of LTD in the SON, this hypothesis cannot be tested based on pharmacological assessment of subunit, unlike in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, since a majority of NMDARs at glutamatergic synapses in the SON appear to contain the ifenprodil-sensitive NR2B subunit. Interestingly, blockade of NR2B receptors caused a defect in LTP and LTD indicating that this NMDAR subtype was required for the induction of both LTP and LTD in the SON.

LTP–LTD relevance in the SON

NMDAR-dependent long-term changes in synaptic strength have been shown to contribute to a variety of neural processes that involve cognition, such as addiction (Wolf, 2003), hyperalgesia (Willis, 2002; Ji et al. 2003), as well as learning and memory (Lynch, 2004). Our results suggest that similar processes may also play an important role in the neuroendocrine hypothalamus. What might be the role of long-term synaptic plasticity in a neural system which is designed to respond to physiological variables that vary on a moment to moment basis? The answer to this question may reside in the fact that LTP and LTD are not irreversible processes, but that they can mediate bi-directional adaptations in synaptic strength over a time scale of minutes. These mechanisms therefore provide an opportunity to adapt the weight of individual excitatory inputs in response to changes in physiological demand. For instance, during parturition and lactation OT neurons display synchronized bursts of action potentials which may be elicited in part by high frequency volleys of presynaptic glutamatergic EPSPs (Jourdain et al. 1998). It is possible therefore that such a pattern of synaptic activation leads to NMDAR-dependent LTP thereby selectively enhancing the weight of these particular synapses relative to others and, as a consequence, sensitizing OT neurons to those particular inputs. Indeed, this phenomenon could explain the progressive increase in burst intensity that is observed during successive episodes of milk-ejection at the onset of individual periods of feeding (Belin & Moos, 1986), and facilitate the activation of OT neurons throughout lactation. Further studies will be required to establish if LTP and LTD play a role in the bursting activity of OT neurons during lactation.

Long-term plasticity in the OVLT-SON pathway

The results obtained with coronal hypothalamic slices indicated that synapses expressing both AMPARs and NMDARs can clearly exhibit activity-dependent plastic changes during focal stimulation proximal to the SON. It is possible, however, that synapses recruited during focal stimulation produce postsynaptic responses that do not reflect physiological conditions (e.g. by stimulating spatially constrained synapses that are not normally coactivated). It was therefore important to establish whether changes in synaptic strength can also occur in an anatomically defined axonal projection. Intracellular recordings from SON neurons in superfused hypothalamic explants revealed that glutamatergic synapses formed by the axons of neurons in the OVLT, most of which are osmosensitive, could be potentiated in response to HFS. Other fibres passing trough or close to the OVLT, might be recruited when this region is stimulated, including fibres originating from the subfornical organ (SFO). Whether this SFO-SON pathway, or other pathways can also undergo potentiation remains to be determined.

Indeed, OVLT neurons activated by hyperosmolality can commonly fire bursts of action potentials displaying instantaneous firing rates of 80 Hz or more (Gentles, 1987), suggesting that LTP of OVLT-SON synapses might occur under these conditions. Previous studies have shown that osmoregulatory mechanisms (i.e. water intake and antidiuresis) cause a gradual and slow (15–30 min) recovery of the plasma osmotic pressure following a hyperosmotic stimulus (Poulain & Wakerley, 1982). Since the overall presynaptic activity OVLT neurons varies in proportion with plasma osmolality (Richard & Bourque, 1995), it seems reasonable to hypothesize that a prolonged period of slow firing on the descending phase of the neuronal response could eventually lead to a depotentiation of OVLT-SON synapses, via LTD, as plasma osmolality returns to baseline. While further studies will be required to test these hypotheses, the reversible induction of LTP at glutamatergic OVLT-SON synapses could provide a significant increase in the determinant role of this pathway on the electrical and secretory activity of SON neurons under hyperosmotic conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Inserm, the Conseil Régional d'Aquitaine, the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). S.H.R.O. is the recipient of an Action Concertée Incitative Jeunes Chercheurs from the Ministère de La Recherche. A.P. is supported by a studentship from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie. C.W.B. is a CIHR Senior Investigator and recipient of a James McGill Research Chair from McGill University.

References

- Belin V, Moos F. Paired recordings from supraoptic and paraventricular oxytocin cells in suckled rats: recruitment and synchronization. J Physiol. 1986;377:369–390. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csaki A, Kocsis K, Kiss J, Halasz B. Localization of putative glutamatergic/aspartatergic neurons projecting to the supraoptic nucleus area of the rat hypothalamus. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:55–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JA, Mulkey RM, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Ca2+ signaling requirements for long-term depression in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:825–833. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kock CP, Burnashev N, Lodder JC, Mansvelder HD, Brussaard AB. NMDA receptors induce somatodendritic secretion in hypothalamic neurones of lactating female rats. J Physiol. 2004;561:53–64. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles SJ. Montreal, Canada: McGill University; 1987. Patterned afferent activity and synaptic plasticity in the magnocellular neurosecretory system. MSc Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Ghamari-Langroudi M, Bourque CW. Caesium blocks depolarizing after-potentials and phasic firing in rat supraoptic neurones. J Physiol. 1998;510:165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.165bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GR, Baimoukhametova DV, Hewitt SA, Rajapaksha WR, Fisher TE, Bains JS. Norepinephrine triggers release of glial ATP to increase postsynaptic efficacy. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1078–1086. doi: 10.1038/nn1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Dudek FE. The effects of the excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid on synaptic transmission to supraoptic neuroendocrine cells. Brain Res. 1988;442:152–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribkoff VK, Dudek FE. Effects of excitatory amino acid antagonists on synaptic responses of supraoptic neurons in slices of rat hypothalamus. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63:60–71. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Bourque CW. NMDA receptor-mediated rhythmic bursting activity in rat supraoptic nucleus neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1992;458:667–687. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Kohno T, Moore KA, Woolf CJ. Central sensitization and LTP: do pain and memory share similar mechanisms? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain P, Israel JM, Dupouy B, Oliet SHR, Allard M, Vitiello S, Theodosis DTT, Poulain DA. Evidence for a hypothalamic oxytocin-sensitive pattern generating network governing oxytocin neurons in vitro. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6641–6649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06641.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombian SB, Hirasawa M, Mouginot D, Chen X, Pittman QJ. Short-term potentiation of miniature excitatory synaptic currents causes excitation of supraoptic neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2542–2553. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombian SB, Zidichouski JA, Pittman QJ. GABAB receptors presynaptically modulate excitatory synaptic transmission in the rat supraoptic nucleus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1166–1179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.2.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, Muller D. Synaptic plasticity and dynamic modulation of the postsynaptic membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:545–550. doi: 10.1038/75714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MA. Long-term potentiation and memory. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:87–136. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Long-term potentiation: a decade of progress? Science. 1999;285:1870–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R, Tsien RW. Presynaptic enhancement shown by whole-cell recordings of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices. Nature. 1990;346:177–180. doi: 10.1038/346177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL, Guthrie PB. Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature. 1984;309:261–263. doi: 10.1038/309261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos FC, Rossi K, Richard P. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors regulates basal electrical activity of oxytocin and vasopressin neurons in lactating rats. Neuroscience. 1997;77:993–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA. Expression mechanisms underlying long-term potentiation: a postsynaptic view. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:721–726. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen R, Hu B, Renaud LP. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist ketamine selectively attenuates spontaneous phasic activity of supraoptic vasopressin neurons in vivo. Neuroscience. 1994;59:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SHR, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. Two distinct forms of long-term depression coexist in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. Neuron. 1997;18:969–982. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliet SHR, Poulain DA. Adenosine-induced presynaptic inhibition of IPSCs and EPSCs in rat hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus neurons. J Physiol. 1999;520:815–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00815.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Crowley WR. Stimulation of oxytocin release in the lactating rat by a central interaction of α1-adrenergic and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid-sensitive excitatory amino acid mechanisms. Endocrinology. 1993a;133:2855–2860. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.7694847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SL, Crowley WR. Stimulation of oxytocin release in the lactating rat by central excitatory amino acid mechanisms: evidence for specific involvement of R,S-α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid-sensitive glutamate receptors. Endocrinology. 1993b;133:2847–2854. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.7694846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain DA, Wakerley JB. Electrophysiology of hypothalamic magnocellular neurons secreting oxytocin and vasopressin. Neuroscience. 1982;7:773–808. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard D, Bourque CW. Synaptic control of rat supraoptic neurones during osmotic stimulation of the organum vasculosum lamina terminalis in vitro. J Physiol. 1995;489:567–577. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader LA, Tasker JG. Presynaptic modulation by metabotropic glutamate receptors of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to hypothalamic magnocellular neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:527–536. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JE, Galarreta M, Foehring RC, Hestrin S, Armstrong WE. Differences in the properties of ionotropic glutamate synaptic currents in oxytocin and vasopressin neuroendocrine neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3367–3375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03367.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. Ifenprodil discriminates subtypes of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor: selectivity and mechanisms at recombinant heteromeric receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis WD. Long-term potentiation in spinothalamic neurons. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;40:202–214. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf ME. LTP may trigger addiction. Mol Interv. 2003;3:248–252. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.5.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuarin JP, Dudek FE. Patch-clamp analysis of spontaneous synaptic currents in supraoptic neuroendocrine cells of the rat hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2323–2331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02323.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]