Abstract

One of the most important features of prolonged weightlessness is a progressive impairment of muscular function with a consequent decrease in exercise capacity. We tested the hypothesis that the impairment in musculo-skeletal function that occurs in microgravity results in a potentiation of the muscle metaboreflex mechanism and also affects baroreflex modulation of heart rate (HR) during exercise. Four astronauts participating in the 16 day Columbia shuttle mission (STS-107) were studied 72–71 days before launch and on days 12–13 in-flight. The protocol consisted of 6 min bicycle exercise at 50% of individual  followed by 4 min of postexercise leg circulatory occlusion (PECO). At rest, systolic (S) and diastolic (D) blood pressure (BP), R-R interval and baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) did not differ significantly between pre- and in-flight measurements. Both pre- and in-flight, SBP increased and R-R interval and BRS decreased during exercise, whereas DBP did not change. During PECO preflight, SBP and DBP were higher than at rest, whereas R-R interval and BRS recovered to resting levels. During PECO in-flight, SBP and DBP were significantly higher whereas R-R interval and BRS remained significantly lower than at rest. The part of the SBP response (Δ) that was maintained by PECO was significantly greater during spaceflight than before (34.5 ± 8.8 versus 13.8 ± 11.9 mmHg, P = 0.03). The tachycardic response to PECO was also significantly greater during spaceflight than preflight (−141.5 ± 25.2 versus −90.5 ± 33.3 ms, P = 0.02). This study suggests that the muscle metaboreflex is enhanced during dynamic exercise in space and that the potentiation of the muscle metaboreflex affects the vagally mediated arterial baroreflex contribution to HR control.

followed by 4 min of postexercise leg circulatory occlusion (PECO). At rest, systolic (S) and diastolic (D) blood pressure (BP), R-R interval and baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) did not differ significantly between pre- and in-flight measurements. Both pre- and in-flight, SBP increased and R-R interval and BRS decreased during exercise, whereas DBP did not change. During PECO preflight, SBP and DBP were higher than at rest, whereas R-R interval and BRS recovered to resting levels. During PECO in-flight, SBP and DBP were significantly higher whereas R-R interval and BRS remained significantly lower than at rest. The part of the SBP response (Δ) that was maintained by PECO was significantly greater during spaceflight than before (34.5 ± 8.8 versus 13.8 ± 11.9 mmHg, P = 0.03). The tachycardic response to PECO was also significantly greater during spaceflight than preflight (−141.5 ± 25.2 versus −90.5 ± 33.3 ms, P = 0.02). This study suggests that the muscle metaboreflex is enhanced during dynamic exercise in space and that the potentiation of the muscle metaboreflex affects the vagally mediated arterial baroreflex contribution to HR control.

One of the most important features of prolonged weightlessness is a progressive impairment of muscular function (Ferretti et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997). Physiological modifications related to exposure to microgravity, e.g. altered blood volume distribution (Leach et al. 1996; Perhonen et al. 2001a), impaired myocardial function (Perhonen et al. 2001b), and a decrease in stroke volume (Shykoff et al. 1996), in addition to the alterations in muscular function (Convertino, 1996; Levine et al. 1996), might contribute to the reduced physical exercise capacity commonly reported after space flight (Convertino, 1996; Levine et al. 1996). The interplay between muscular (Ferretti et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997), haemodynamic and body fluid modifications occurring in microgravity (Watenpaugh & Hargens, 1996) might also alter the neural control mechanisms underlying the cardiovascular responses to exercise that are normally operating on the ground.

Whether and in which way microgravity-induced impairment of the muscular function affects the neural mechanisms of cardiovascular regulation is still poorly understood. Cardiovascular and autonomic responses to exercise have been reported to be either impaired (Pagani et al. 2001; Spaak et al. 2001) or preserved after simulated (Essfeld et al. 1993; Kamiya et al. 2000) or actual (Fu et al. 2002) microgravity conditions. However, the relative contribution provided by the different neural mechanisms involved in cardiovascular regulation during exercise, namely central command and the reflex drive from contracting muscles (Mitchell, 1990), has been directly addressed by two studies only, which suggested an unaltered muscle metaboreflex control of cardiovascular and sympathetic responses during simulated (Kamiya et al. 2000) or actual microgravity (Fu et al. 2002). No study has until now addressed the occurrence of possible changes in baroreflex control of HR during exercise in space.

All the studies performed so far dealing with cardiovascular responses to exercise during spaceflight have used static exercise of small muscle masses (i.e. handgrip) as a convenient model of muscular exercise. However, microgravity-induced muscular impairment involves mainly the antigravity muscles, i.e. leg muscles, which are those primarily involved in the reduced exercise capacity, whereas arm muscles are not ordinarily weight bearing and hence are less representative of the marked changes in the musculo-skeletal system induced by the microgravity environment (Ferretti et al. 1997; Zhang et al. 1997). In addition, cardiovascular responses to exercise and the underlying mechanisms are strongly dependant on the exercise mode, i.e. static versus dynamic, and the size of the muscle mass involved (Mitchell et al. 1980; Iellamo et al. 1999a).

Therefore our study was originally designed to investigate the cardiovascular responses to whole body dynamic exercise during and after spaceflight to test the hypothesis that the impairment in musculo-skeletal function that may occur in microgravity, e.g. decrease O2 delivery and oxidative enzyme activity (Ferretti et al. 1997), results in a potentiation of the muscle metaboreflex mechanism during whole body dynamic exercise. In addition, since the arterial baroreflex plays a pivotal role in cardiovascular regulation during exercise (O'Leary, 1996; Iellamo, 2001a) and an impairment in arterial baroreflex control of heart rate has been reported in the resting state during spaceflight (Fritsch-Yelle et al. 1992), we also investigated whether and in which way the neural mechanisms underlying cardiovascular responses to whole body dynamic exercise affect the integrated baroreflex control of the sinoatrial node.

To accomplish this goal, moderate intensity, constant load bicycle exercise followed by postexercise occlusion of leg circulation to maintain the chemical stimulation of muscle afferents (i.e. metaboreflex activation) was planned to be performed before, during and after prolonged space flight, in the context of the ESA–NASA mission STS-107 of the space shuttle Columbia. The tragic end of the mission, involving the loss of the shuttle and its crew, prevented completion of the experimental protocol. The present paper therefore includes the results obtained during the ground experiments preceding launch and those from the experimental sessions performed during space flight in the context of this mission only.

Methods

Subjects

We studied four astronauts (three males and one female) of the 16 day mission STS-107 of the space shuttle Columbia. Their mean age was 45 years (range 42–49). All subjects were in excellent health, as determined by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) medical evaluation board. The subjects gave their written consent to the experimental procedures after being informed of their aim and nature. The study was conducted under the guidelines issued by the NASA Johnson Space Center Human Research Policies and Procedure Committee and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the institutions of the principal investigators. It conformed with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Instrumentation and experimental protocol

Experiments were performed on days 72–71 before launch and on days 12–13 in-flight. During the experiments the following signals were recorded: (1) continuous arterial pressure at the finger level by a modified Portapres device (Cardipres, Finapres Medical System, Aharnem, the Netherlands), (2) R-R interval from ECG (1 channel from Portapres), and (3) a respiratory signal from an inductance plethysmograph. All measuring devices were included in the Advanced Respiratory Monitoring System (ARMS, Damec, Odense, Denmark) module, a research facility provided by the European Space Agency which was available on the ground and on board the shuttle mission STS-107. This system is a multiuser facility supporting human physiology research by measuring gas compositions during respiration of different gas mixtures, heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP) and respiratory rate. Both pre- and in-flight, the study protocol consisted of 5 min rest followed by 6 min bicycle exercise at 50% of the workload producing the individual's maximal  at 1 g 15 s before cessation of exercise two pneumatic cuffs placed, as high as possible, on the thighs were automatically inflated to suprasystolic pressure and leg postexercise circulatory occlusion (PECO) was maintained for 4 min after the end of exercise. Exercise was performed in the seated posture both pre- and in-flight.

at 1 g 15 s before cessation of exercise two pneumatic cuffs placed, as high as possible, on the thighs were automatically inflated to suprasystolic pressure and leg postexercise circulatory occlusion (PECO) was maintained for 4 min after the end of exercise. Exercise was performed in the seated posture both pre- and in-flight.

Data analysis

No special data pretreatment was required for our experiments. Data acquisition, digitalization (at 12 bit resolution and 100 Hz sampling rate) and storage were performed by the standard software which controlled ARMS during the experiments. In-flight signals were down-linked to Earth in real time to allow investigators to monitor the quality of the recordings and, in case of problems, to propose adequate solutions while the experiments were in progress, and this allowed the rescue of most of the in-flight data in spite of the loss of Columbia before landing.

Systolic (S) BP and diastolic (D) BP and the R-R interval were derived beat-by-beat from BP and ECG signals. All beat-by-beat values recorded during rest, exercise and PECO were averaged, separately for each experimental condition.

Analysis of baroreflex sensitivity

Baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) was dynamically assessed by the sequence technique as previously reported (Di Rienzo et al. 1985; Bertinieri et al. 1988; Parati et al. 1988; Iellamo et al. 1999a). Briefly, this technique is based on automatic scanning of the systolic (S) BP and R-R interval series, searching for spontaneous sequences of three or more consecutive heart beats characterized by a progressive increase in SBP, accompanied, with a one beat lag, by a progressive R-R interval lengthening or, vice versa, by a progressive SBP reduction followed by R-R interval shortening. For each sequence, the regression line is computed between SBP and R-R interval values, and the mean slope of the SBP–R-R interval relationship, obtained by averaging all slopes computed within a given test period, is calculated and taken as a measure of the average spontaneous BRS for that period.

Statistical analysis

Each variable was checked for normality of distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnof test. Since all variables were normally distributed, the significance of differences in the reported variables among rest, exercise and PECO (both pre- and in-flight) was evaluated by analysis of variance for repeated measures. Pairwise multiple comparison procedures were performed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Differences between pre- and in-flight data were compared by Student's paired t test. Values are presented as means ± s.e.m. Differences were considered statistically significant when P was < 0.05.

Results

Cardiovascular responses to exercise and postexercise leg circulatory occlusion

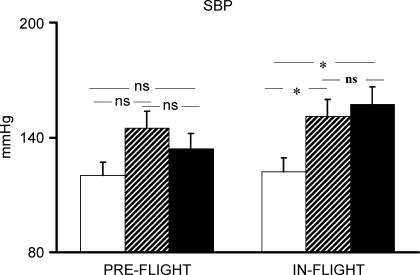

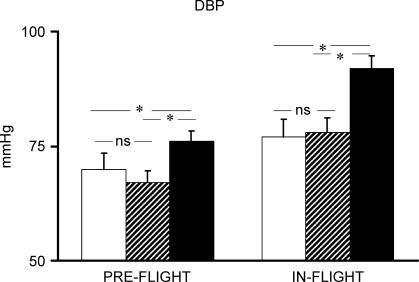

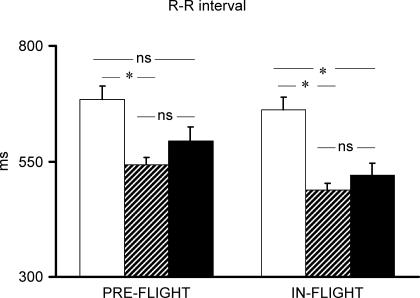

Pre-flight average maximal  of the four astronauts was 2684 ± 367.1 ml min−1. Individual cardiovascular responses to exercise and PECO before and during spaceflight are reported in Table 1. Baseline cardiovascular variables did not differ significantly between pre- and in-flight measurements. Before spaceflight, during exercise R-R interval was significantly reduced, and SBP increased, although the increase did not reach statistical significance, whereas diastolic (D) BP did not change from resting values (Figs 1 and 2). During postexercise circulatory occlusion, R-R interval recovered toward resting values (Fig. 3), whereas SBP remained higher than the baseline level (albeit not significantly) and DBP significantly increased above exercise and resting values (Figs 1 and 2).

of the four astronauts was 2684 ± 367.1 ml min−1. Individual cardiovascular responses to exercise and PECO before and during spaceflight are reported in Table 1. Baseline cardiovascular variables did not differ significantly between pre- and in-flight measurements. Before spaceflight, during exercise R-R interval was significantly reduced, and SBP increased, although the increase did not reach statistical significance, whereas diastolic (D) BP did not change from resting values (Figs 1 and 2). During postexercise circulatory occlusion, R-R interval recovered toward resting values (Fig. 3), whereas SBP remained higher than the baseline level (albeit not significantly) and DBP significantly increased above exercise and resting values (Figs 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Individual cardiovascular responses to exercise and postexercise muscle ischaemia

| Pre-flight | In-flight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astronaut | Baseline | Exercise | PECO | Baseline | Exercise | PECO |

| SBP (mmHg) | ||||||

| 1 (m) | 126 | 149 | 166 | 168 | 185 | 217 |

| 2 (m) | 107 | 136 | 130 | 106 | 143 | 143 |

| 3 (m) | 122 | 162 | 130 | 114 | 165 | 157 |

| 4 (f) | 125 | 135 | 109 | 102 | 111 | 111 |

| Mean ± s.e.m. | 120.0 ± 4.4 | 145.5 ± 6.4 | 134 ± 11.8 | 122.5 ± 15.4 | 151.0 ± 15.8* | 157.0 ± 22.2* |

| DBP (mmHg) | ||||||

| 1 | 66 | 62 | 79 | 104 | 101 | 127 |

| 2 | 71 | 70 | 81 | 65 | 69 | 81 |

| 3 | 71 | 63 | 70 | 66 | 69 | 84 |

| 4 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 72 | 73 | 74 |

| Mean ± s.e.m. | 70.0 ± 1.4 | 67.0 ± 2.7 | 76.0 ± 2.5* | 76.8 ± 9.2 | 78.0 ± 7.7 | 91.5 ± 12.0* |

| R-R interval (ms) | ||||||

| 1 | 639 | 494 | 482 | 611 | 451 | 425 |

| 2 | 694 | 575 | 561 | 730 | 508 | 560 |

| 3 | 829 | 618 | 817 | 770 | 497 | 698 |

| 4 | 578 | 481 | 518 | 538 | 497 | 400 |

| Mean ± s.e.m. | 685.0 ± 53.5 | 542.0 ± 32.8* | 594.5 ± 75.9 | 662.3 ± 53.4 | 488.3 ± 12.7* | 520.8 ± 68.7* |

| BRS (ms mmHg−1) | ||||||

| 1 | 5.0 | 1.8 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 4.7 | 5.0 |

| 3 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 3.8 |

| 4 | 4.9 | 2.4 | 4.0 | 6.4 | 3.4 | 3.4 |

| Mean ± s.e.m. | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 2.2*± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 3.6*± 0.6 | 3.4 ± 0.7* |

m, male; f, female; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; BRS, baroreflex sensitivity; PECO, postexercise circulatory occlusion.

P < 0.05 versus baseline.

Figure 1. SBP response to exercise and postexercise circulatory occlusion preflight and in-flight.

Open bars indicate rest; hatched bars, exercise; filled bars, postexercise circulatory occlusion. *P < 0.05.

Figure 2. DBP response to exercise and postexercise circulatory occlusion preflight and in-flight.

Open bars indicate rest; hatched bars, exercise; filled bars, postexercise circulatory occlusion. *P < 0.05.

Figure 3. R-R interval response to exercise and postexercise circulatory occlusion preflight and in-flight.

Open bars indicate rest; hatched bars, exercise; filled bars, postexercise circulatory occlusion. *P < 0.05.

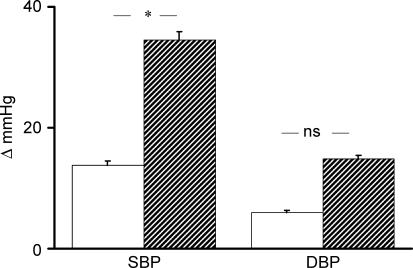

During spaceflight, SBP increased significantly during exercise, and remained significantly higher than at rest during PECO. DBP did not change from rest during exercise, but increased significantly above exercise and resting values during PECO (Figs 1 and 2). R-R interval decreased significantly during exercise, and remained significantly lower than the resting level during PECO (Fig. 3). The rise in SBP which occurred from rest to exercise and was maintained by PECO was significantly greater during spaceflight than before. A similar, albeit not statistically significant, trend was observed for DBP (Fig. 4). The tachycardic response to PECO was also significantly greater during spaceflight than preflight (−141.5 ± 25.2 versus −90.5 ± 33.3 ms, P = 0.02).

Figure 4. Changes (Δ) in exercise-induced SBP and DBP increase that were maintained by postexercise circulatory occlusion preflight (open bars) and in-flight (hatched bars).

*P < 0.05. versus preflight

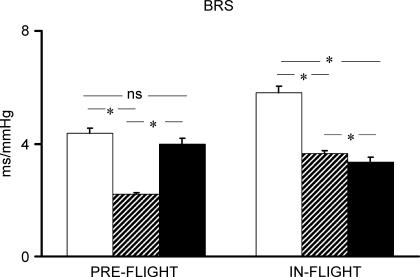

In baseline conditions, BRS decreased significantly from rest during exercise and recovered to resting level during PECO. During spaceflight, BRS decreased significantly during exercise and remained significantly lower than at rest also during PECO (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. BRS response to exercise and postexercise circulatory occlusion preflight and in-flight.

Open bars indicate rest; hatched bars, exercise; filled bars, postexercise circulatory occlusion. *P < 0.05.

No significant differences were detected in the number of spontaneous baroreflex sequences between preflight and in-flight in any experimental conditions (rest: 14.0 ± 4.5 versus 11 ± 5; exercise: 17.0 ± 2.1 versus 11.0 ± 2.2; PECO: 27.3 ± 2.7 versus 18.0 ± 3.7, P > 0.05 for all comparisons).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the neural mechanisms of cardiovascular regulation during whole-body dynamic exercise in space. The main findings of the present study are (1) that a microgravity environment results in an enhancement of the muscle metaboreflex mechanism in the regulation of the cardiovascular responses to dynamic exercise, and (2) that the microgravity environment affects the modulatory effect of the muscle metaboreflex on the integrated baroreflex control of the sinus node, with the latter mechanism being possibly involved in the cardiovascular response to dynamic exercise.

Role of the muscle metaboreflex

When blood flow and oxygen delivery to contracting muscles are insufficient for the rate of metabolism, chemical products of muscle metabolism accumulate within the muscle and stimulate group III and IV afferents (Rotto & Kaufman, 1988). Activation of these afferents elicits a reflex increase in sympathetic activity to the heart and vasculature which increases HR and BP; this is termed the muscle metaboreflex (Kaufman et al. 1983; Mitchell, 1990). One of the most important consequences of a prolonged stay in a microgravity environment is a progressive impairment of the musculo-skeletal function, which becomes manifest as muscle atrophy and as functional changes in quadriceps muscle fibres, such as decreased oxidative enzyme activity, decreased mitochondrial volume density and decreased capillary length leading to decreased O2 delivery to active muscles (Ferretti et al. 1997). These alterations are associated with a relative decrease in stroke volume at submaximal exercise work loads (Shykoff et al. 1996), resulting in a decreased O2 transport capacity by the cardiovascular system which outweighs the decrease in  (Ferretti et al. 1997). The decrease in O2 delivery and O2 transport capacity to the active muscles might result in a greater engagement of the muscle metaboreflex during dynamic exercise (Sheriff et al. 1987). The volume reduction surrounding the interstitial muscle receptors, as a consequence of the relative dehydratation during spaceflight, which would affect mainly the lower body, might act in the same direction (Essfeld et al. 1993). Our results of a maintained and even increased SBP and DBP over and above resting and even exercise levels at the time of PECO during spaceflight would indicate that the muscle metaboreflex is enhanced during dynamic (bicycle) exercise in space. The part of the pressor and tachycardic responses (i.e. change from rest) that were maintained by PECO (i.e. by the muscle metaboreflex) was greater during spaceflight than on the ground, further supporting the conclusion of an augmented muscle metaboreflex activation during dynamic exercise in space. The possibility that some deconditioning might have resulted in a relatively greater involvement in central command signals to maintain the target level of effort, i.e. the work load at 50% of

(Ferretti et al. 1997). The decrease in O2 delivery and O2 transport capacity to the active muscles might result in a greater engagement of the muscle metaboreflex during dynamic exercise (Sheriff et al. 1987). The volume reduction surrounding the interstitial muscle receptors, as a consequence of the relative dehydratation during spaceflight, which would affect mainly the lower body, might act in the same direction (Essfeld et al. 1993). Our results of a maintained and even increased SBP and DBP over and above resting and even exercise levels at the time of PECO during spaceflight would indicate that the muscle metaboreflex is enhanced during dynamic (bicycle) exercise in space. The part of the pressor and tachycardic responses (i.e. change from rest) that were maintained by PECO (i.e. by the muscle metaboreflex) was greater during spaceflight than on the ground, further supporting the conclusion of an augmented muscle metaboreflex activation during dynamic exercise in space. The possibility that some deconditioning might have resulted in a relatively greater involvement in central command signals to maintain the target level of effort, i.e. the work load at 50% of  determined on the ground, cannot be totally ruled out. However, we did not expect that actual workload during flight would be a relatively higher fraction of maximal O2 consumption as determined preflight, since the decline in

determined on the ground, cannot be totally ruled out. However, we did not expect that actual workload during flight would be a relatively higher fraction of maximal O2 consumption as determined preflight, since the decline in  at submaximal workload in space is small (Levine et al. 1996) and prolonged bed rest (42 days) led to a greater decrease in cardiovascular O2 transport capacity, as a consequence of muscular alterations, than reduction in

at submaximal workload in space is small (Levine et al. 1996) and prolonged bed rest (42 days) led to a greater decrease in cardiovascular O2 transport capacity, as a consequence of muscular alterations, than reduction in  (Ferretti et al. 1997).

(Ferretti et al. 1997).

Our finding of an enhanced muscle metaboreflex in space is partially at variance with previous reports of unaltered muscle metaboreflex contribution to cardiovascular regulation during exposure to simulated (Spaak et al. 2001) or actual (Fu et al. 2002) microgravity. The most likely explanation for these different findings relates both to the different mode of exercise and to the different muscle masses under investigation. Previous studies examined cardiovascular and neural responses to static exercise and postexercise circulatory occlusion of small (forearm) muscles (Kamiya et al. 2000; Fu et al. 2002) whereas we studied the responses to dynamic exercise of larger (leg) muscle masses. Both the type of exercise and the muscle masses engaged in muscular activity are strong determinants of both the cardiovascular responses and the relative contribution afforded by the different neural mechanisms involved in cardiovascular regulation (Mitchell et al. 1980; Galbo et al. 1987; Seals, 1993; Iellamo et al. 1997, 1999a). For example, HR regulating mechanisms are substantially different during dynamic as opposed to static exercise, with a predominant role of reflex drive from muscles in the former and of central command in the latter (Galbo et al. 1987; Victor et al. 1987; Victor & Seals, 1989; Rowell & O'Leary, 1990). In addition, the alteration in muscle function and structure induced by microgravity involves mainly the antigravity muscles, that is, leg rather than arm muscles, and this alteration would provide the substrate for the augmented muscle metaboreflex we observed. We speculate that the enhancement of the muscle metaboreflex might occur in the attempt to compensate, in part, for the reduced O2 transport capacity occurring after exposure to a microgravity environment (Convertino, 1996; Shykoff et al. 1996; Ferretti et al. 1997). In fact, the metaboreflex has the capability to increase ventricular performance and O2 delivery to active skeletal muscles during dynamic exercise and to induce peripheral vasoconstriction in non-active regions (O'Leary & Augustyniak 1998; O'Leary et al. 1999; Augustyniak et al. 2000), with the aim of eliminating any existing mismatch between O2 delivery and O2 demand in the exercising skeletal muscle during moderate intensity dynamic exercise. It is worth noting that a potentiation of the muscle metaboreflex has been reported in several (Piepoli et al. 1996; Greve et al. 1999; Hammond et al. 2000), although not all (Stern et al. 1991; Middlekauff et al. 1985, 2001; Sinoway & Li, 2005), studies in patients with heart failure, who feature some haemodynamic and muscles alterations (Lipkin et al. 1988; Sullivan et al. 1990; Drexler et al. 1992) like those ensuing in astronauts during spaceflight.

Unfortunately, missing data from the experiments that we could not perform after return to earth gravity prevents a full definition of the role of the muscle metaboreflex in regulating the cardiovascular responses to dynamic exercise on re-entry after microgravity exposure.

Role of the arterial baroreflex

In keeping with some (Bristow et al. 1971; Pagani et al. 1988; Lucini et al. 1995; Iellamo et al. 1998) but not all (Potts et al. 1993; Papelier et al. 1994; Norton et al. 1999; Ogoh et al. 2005) previous studies, before spaceflight we observed a decrease in BRS during dynamic exercise which recovered to resting levels during muscle metaboreflex activation by PECO. Differences in baroreflex testing methodology might account for these different results (see Iellamo, 2001a, b for review of this topic). Contrary to this, during exercise in microgravity the decrease in BRS was still maintained during the muscle metaboreflex activation, when central command (and muscle mechanoreceptor stimulation as well) was absent. These findings would indicate that a greater engagement of the muscle metaboreflex, as in microgravity conditions, with the attendant increase in sympathetic activity (Mark et al. 1985; Victor & Seals, 1989; O'Leary, 1993; O'Leary & Augustyniak 1998), is capable of blunting the integrated baroreflex mechanisms controlling heart period (Pagani et al. 1982; Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. 1987). The blunted reflex control of HR during exercise could be also due, at least in part, to central influences overcoming reflex HR modulation and aimed at increasing cardiac output, while preserving the reflex control of BP, thus excluding a full resetting of the arterial baroreflex (Mancia et al. 1982). However, central command was surely not operating during PECO. The maintained inhibition of the vagal–cardiac baroreflex modulation by the muscle metaboreflex could have contributed to the greater tachycardic response to PECO observed during spaceflight.

At variance with previous studies (Fritsch-Yelle et al. 1992) we did not observe significant changes in resting BRS during flight compared to preflight. Again, differences in baroreflex testing methodology might account for this different result. Previous studies (Fritsch-Yelle et al. 1992) employed the neck collar to assess the carotid–cardiac baroreceptor reflex whereas we evaluated the integrated arterial baroreceptor–HR reflex at the current, operating level of BP and HR. One advantage of the sequences technique is that it allows assessment of the baroreflex modulation of HR dynamically, relying on a natural stimulus of physiological magnitude, that is, spontaneous BP increases and decreases, without having to induce any pharmacological or mechanical disturbance from outside the cardiovascular system. As such, it appears particularly suitable for employment during space missions (Parati et al. 2000). However, the spontaneous baroreflex method we used reflects the responses to rapid, transient changes in arterial pressure, which are vagally mediated, while it does not allow investigation of the slower sympathetic component of the baroreceptor–cardiac reflex (Ogoh et al. 2005).

How central command and the reflex drive from muscles affect the cardiac component of the arterial baroreflex during exercise is a surely complex and still undefined issue. Experimental evidence indicates that both these mechanisms are capable of modulating the arterial baroreflex during exercise, causing either a ‘resetting’ or a decrease in the gain of the baroreceptor–cardiac reflex (Iellamo, 2001a,b; Ogoh et al. 2002). It has been argued that such a modulating effect in the direction of ‘resetting’ or decreasing BRS is strongly dependent on the type as well as the intensity and the size of muscle masses engaged in exercise (Iellamo, 2001a). The maintained decrease in BRS during PECO during spaceflight, which was accompanied by greater tachycardic and pressor responses, would suggest that greater metaboreflex-induced sympathetic activation could be an adequate stimulus for decreasing the gain of the integrated baroreceptor–cardiac reflex. In this context, it may be pertinent to recall that sympathetic activation normally opposes the negative feedback mechanisms of baroreflex origin (Pagani et al. 1982; Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. 1987; Ferrari et al. 1991). On the other hand, the possibility of a direct action of the muscle metaboreflex on parasympathetic pathways seems unlikely because the metaboreflex operates principally via changes in sympathetic activity with little control over parasympathetic activity (O'Leary, 1993). The question of whether and to what extent muscle mechanoreceptor stimulation might contribute to the decrease in BRS observed during exercise cannot be answered by the present investigation. However, pure muscle mechanoreflexes were surely not engaged during postexercise circulatory occlusion.

The interest of the contribution provided by our paper relies on the fact that, to the best of our knowledge, it offers for the first time data on baroreflex modulation of the sinoatrial node during exercise and related mechanisms under actual microgravity conditions.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The first limitation is the small number of subjects, which is, however, unavoidable on space flight missions and is a feature of all previous papers published in this difficult field. Hence, the physiological interindividual variability of the results may have prevented the achievement of statistical significance in some instances, despite the appearance of clear trends. Our results on SBP response to exercise in baseline conditions is just an example of this. For this reason we have presented also individual data.

There are other possible confounding factors to be considered in the interpretation of our results, which are, however, a common feature of all manned space missions. These include, first, performing experiments in a shuttle environment, which is remarkably different from that of a standardized research laboratory; second, the psychological excitement which may be present both during baseline data collection and even more so during space flight, possibly leading to emotional arousal and interference with the subtle mechanisms involved in reflex cardiac regulation; third, the uninterrupted interaction with other crew members and the ground control staff, which might also have added noise to the physiological recordings; and, finally, the possible after-effects of previously performed experiments also planned during the mission on measurements that were supposed to be taken in ‘control’ conditions. All these factors, might have affected the results of our study, and might explain, for example, the low resting BRS values we observed both pre- and in-flight (Iellamo et al. 2002; Lucini et al. 2002). In an attempt to minimize as much as possible their effects, all the experiments, both pre- and in-flight, followed the same order, and were planned to be performed at approximately the same time during the day. Nevertheless, some of the above factors could have escaped control. Despite these limitations, we found consistent changes in the muscle metaboreflex and arterial baroreflex modulation of the sinus node during exercise in space as compared to baseline, which supports the physiological reliability of our data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the muscle metaboreflex contribution to cardiovascular regulation during moderate intensity dynamic leg exercise is enhanced during spaceflight and that such enhancement of the muscle metaboreflex affects the integrated baroreflex control of sinus node, suggesting that the latter mechanism may be involved in the cardiovascular response to dynamic exercise in actual microgravity conditions. We speculate that the enhancement of the muscle metaboreflex is a response to the reduced O2 transport occurring after exposure to microgravity, with the aim of counteracting any existing mismatch between O2 delivery and O2 demand in the exercising skeletal muscle during moderate intensity dynamic exercise.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by the European Space Agency, and by grants from the Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI), and Ministero dell'Istruzione Università e Ricerca (MIUR COFIN 2003).

References

- Augustyniak RA, Ansorge EJ, O'Leary DS. Muscle metaboreflex control of cardiac output and peripheral vasoconstriction exhibit different latencies. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H530–H537. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.2.H530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertinieri G, Di Rienzo M, Cavallazzi A, Ferrari AV, Pedotti A, Mancia G. Evaluation of baroreceptor reflex by blood pressure monitoring in unanesthetized cats. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H377–H383. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.2.H377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow JD, Braun EB, Cunningham DJC, Howson MG, Strange Petersen E, Pickering TG, Sleight P. Effect of bicycling on the baroreflex regulation of pulse interval. Circ Res. 1971;38:582–593. [Google Scholar]

- Convertino VA. Exercise and adaptation to microgravity environment. In: Fregly MJ, Blatties CM, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Environmental Physiology. Vol. 2. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1996. pp. 815–843. chap 36. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rienzo M, Bertinieri G, Mancia G, Pedotti A. A new method for evaluating the baroreflex role by a joint pattern analysis of pulse interval and systolic blood pressure series. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1985;23(Suppl. 1):313–314. [Google Scholar]

- Drexler H, Riede U, Munzel T, Konig H, Funke E, Just H. Alterations of skeletal muscle in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85:1751–1759. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essfeld D, Baum K, Hoffmann U, Stegemann J. Effects of microgravity on interstitial muscle receptors affecting heart rate and blood pressure during static exercise. J Clin Invest. 1993;71:704–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari AU, Daffonchio A, Franzelli C, Mancia G. Potentiation of the baroreceptor-heart rate reflex by sympathectomy in conscious rats. Hypertension. 1991;18:230–235. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti G, Antonutto G, Denis C, Hoppeler H, Minetti AE, Narici MV, Desplanches D. The interplay of central and peripheral factors in limiting maximal O2 consumption in man after prolonged bed rest. J Physiol. 1997;501:677–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.677bm.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritsch-Yelle JM, Charles JB, Bennett BS, Jones MM, Eckberg DL. Short-duration space flight impairs human carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex responses. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73:664–671. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Levine BD, Pawelczyk JA, Ertl AC, Diedrich A, Cox JF, Zuckerman JH, Raya CA, Smith ML, Iwase S, Saito M, Sugiyama Y, Mano T, Zhang R, Iwasaki K, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Jr, Cooke WH, Robertson RM, Baisch FJ, Blomqvist CG, Eckberg DL, Robertson D, Biaggioni I. Cardiovascular and sympathetic neural responses to handgrip and cold pressor stimuli in humans before, during and after spaceflight. J Physiol. 2002;544:653–664. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbo H, Kjaer M, Secher NH. Cardiovascular, ventilatory and catecholamine responses to maximal dynamic exercise in partially curarized man. J Physiol. 1987;389:557–568. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnecchi-Ruscone T, Lombardi F, Malfatto G, Malliani A. Attenuation of baroreceptive mechanisms by cardiovascular sympathetic afferent fibers. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H787–H791. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.4.H787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve DA, Clark AL, McCann GP, Hillis WS. The ergoreflex in patients with chronic stable heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1999;68:157–164. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00349-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond RL, Augustyniak RA, Rossi NF, Churchill PC, Lapanowski K, O'Leary DS. Heart failure alters the strength and mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H818–H828. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.3.H818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F. Neural mechanisms of cardiovascular regulation during exercise. Auton Neurosci. 2001a;90:66–75. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F. Neural control of the cardiovascular system during exercise. It Heart J. 2001b;2:200–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Legramante JM, Pigozzi F, Spataro A, Norbiato G, Lucini D, Pagani M. Conversion from vagal to sympathetic predominance with strenuous training in high performance world class athletes. Circulation. 2002;105:2719–2724. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018124.01299.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Legramante JM, Raimondi G, Castrucci F, Damiani C, Foti C, Peruzzi G, Caruso I. The effects of isokinetic, isotonic and isometric submaximal exercise on heart rate and blood pressure. Eur J Appl Physiol. 1997;75:89–96. doi: 10.1007/s004210050131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Massaro M, Legramante JM, Raimondi G, Peruzzi G, Galante A. Spontaneous baroreflex modulation of heart rate during incremental exercise in humans. FASEB J. 1998;12:A692. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Massaro M, Raimondi G, Peruzzi G, Legramante JM. Role of muscular factors in cardiorespiratory responses to static exercise: contribution of reflex mechanisms. J Appl Physiol. 1999a;86:174–180. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Pizzinelli P, Massaro M, Raimondi G, Peruzzi G, Legramante JM. Muscle metaboreflex contribution to sinus node regulation during static exercise. Insights from spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Circulation. 1999b;100:27–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Iwase S, Michikamia D, Fua Q, Mano T. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during handgrip and post-handgrip muscle ischemia after exposure to simulated microgravity in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00995-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MP, Longhurst JC, Rybicki KJ, Wallach JH, Mitchell JH. Effect of static muscular contraction on impulse activity of groups III and IV afferents in cat. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:105–112. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach CS, Alfrey CP, Suki WA, Leonard JI, Rambaut PC, Inners LD, Smith SM, Lane HW, Krauhs JM. Regulation of body fluid compartments during short-term space flight. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:105–116. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine BD, Lane LD, Watenpaugh DE, Gaffney FA, Buckey JC, Jr, Blomquist CG. Maximal exercise performance after adaptation to microgravity. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:686–694. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin DP, Jones DA, Round JM, Poole-Wilson PA. Abnormalities of skeletal muscle in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 1988;18:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(88)90164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucini D, Norbiato G, Clerici M, Pagani M. Hemodynamic and autonomic adjustments to real life stress conditions in humans. Hypertension. 2002;39:184–188. doi: 10.1161/hy0102.100784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucini D, Trabucchi V, Malliani A, Pagani M. Analysis of initial autonomic adjustments to moderate exercise in humans. J Hypertens. 1995;13:1660–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancia G, Ferrari A, Gregorini L, Parati G, Pomidossi G. Effects of isometric exercise on the carotid baroreflex in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 1982;4:245–250. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark AL, Victor RG, Nerhed C, Wallin BG. Microneurographic studies of the mechanisms of sympathetic nerve responses to static exercise in humans. Circ Res. 1985;57:461–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.57.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlekauff HR, Nitzche EU, Hoh CK, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Hage A, Moriguchi JD, Mitchell JH. Cardiovascular control during exercise: central and reflex mechanisms. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:D34–D41. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)91053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlekauff HR, Nitzsche EU, Hoh CK, Hamilton MA, Fonarow GC, Hage A, Moriguchi JD. Exaggerated muscle mechanoreflex control of reflex renal vasoconstriction in heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1714–1719. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JH. Neural control of the circulation during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1990;22:141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JH, Payne FC, Saltin B, Schibye B. The role of muscle mass in the cardiovascular response to static contractions. J Physiol. 1980;309:45–54. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton KH, Boushel R, Strange S, Saltin B, Raven PB. Resetting of the carotid arterial baroreflex during dynamic exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:332–338. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.1.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS. Autonomic mechanisms of muscle metaboreflex control of heart rate. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:1748–1754. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.4.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS. Heart rate control during exercise by baroreceptors and skeletal muscle afferents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:210–217. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199602000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS, Augustyniak RA. Muscle metaboreflex increases ventricular performance in conscious dogs. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H220–H224. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary DS, Augustyniak RA, Ansorge EJ, Collins HL. Muscle metaboreflex improves O2 delivery to ischemic active skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1399–H1403. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.4.H1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Fisher JP, Dawson EA, White MJ, Secher NH, Raven PB. Autonomic nervous system influence on arterial baroreflex control of heart rate during exercise in humans. J Physiol. 2005;566:599–611. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoh S, Wasmund WL, Keller D, Gallagher KM, Mitchell JH, Raven PB. Role of central command in carotid baroreflex resetting in humans during static exercise. J Physiol. 2002;543:349–364. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Iellamo F, Lucini D, Cerchiello M, Castrucci F, Pizzinelli P, Porta A, Malliani A. Selective impairment of excitatory pressor responses after prolonged simulated microgravity in humans. Auton Neurosci. 2001;91:85–95. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Pizzinelli P, Bergamaschi M, Malliani A. A positive feedback sympathetic pressor reflex during stretch of the thoracic aorta in conscious dogs. Circ Res. 1982;50:125–132. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Somers V, Furlan R, Dell'Orto S, Conway J, Baselli G, Cerutti S, Sleight P, Malliani A. Changes in autonomic regulation induced by physical training in mild hypertension. Hypertension. 1988;12:600–610. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.12.6.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papelier Y, Escourrou P, Gauthier JP, Rowell LB. Carotid baroreflex control of blood pressure and heart rate in men during dynamic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:502–506. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Di Rienzo M, Bertinieri G, Pomidossi G, Casadei R, Groppelli A, Pedotti A, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. Evaluation of the baroreceptor-heart rate reflex by 24-hour intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring in humans. Hypertension. 1988;12:214–222. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.12.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parati G, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. How to measure baroreflex sensitivity: from the cardiovascular laboratory to daily life. J Hypertens. 2000;18:7–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perhonen MA, Franco F, Lane LD, Buckey JC, Blomquist CG, Zerwekh JE, Peshock RM, Weatherall PT, Levine BD. Cardiac atrophy after bed rest and space flight. J Appl Physiol. 2001a;91:645–653. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.2.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perhonen MA, Zuckerman JH, Levine BD. Deterioration of left ventricular chamber performance after bed rest: ‘cardiovascular deconditioning’ or hypovolemia? Circulation. 2001b;103:1851–1857. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.14.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepoli M, Clark AL, Volterrani M, Adamopoulos S, Sleight P, Coats AJS. Contribution of muscle afferents to the hemodynamic, autonomic, and ventilatory responses to exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Effects of physical training. Circulation. 1996;93:940–949. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.5.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts JT, Shi X, Raven PB. Carotid baroreflex responsiveness during dynamic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1928–H1938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.6.H1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotto DM, Kaufman MP. Effect of metabolic products of muscular contraction on discharge of group III and IV afferents. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:2306–2313. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, O'Leary DS. Reflex control of the circulation during exercise: chemoreflexes and mechanoreflexes. J Appl Physiol. 1990;69:407–418. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.69.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals DR. Influence of active muscle size on sympathetic nerve discharge during isometric contractions in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1993;75:1426–1431. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.3.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheriff DD, O'Leary DS, Scher AM, Rowell LB. Does inadequate O2 delivery trigger the pressor response to muscle hypoperfusion during exercise? Am J Physiol. 1987;253:H305–H310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shykoff BE, Farhi LE, Olszowka AJ, Pendergast DR, Rokitka MA, Eisenhardt CG, Morin RA. Cardiovascular response to submaximal exercise in sustained microgravity. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:26–32. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinoway LI, Li J. A perspective on the muscle reflex: implications for congestive heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:5–22. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01405.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaak J, Sundblad P, Linnarsson D. Impaired pressor response after spaceflight and bed rest: evidence for cardiovascular disfunction. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2001;85:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s004210100429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterns DA, Ettinger SM, Gray KS, Whisler SK, Mosher TJ, Smith MB, Sinowai LI. Skeletal muscle metaboreceptor exercise responses are attenuated in heart failure. Circulation. 1991;84:2034–2039. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Green HJ, Cobb FR. Skeletal muscle biochemistry and histology in ambulatory patients with long-term heart failure. Circulation. 1990;81:518–527. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.2.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Seals DR. Reflex stimulation of sympathetic outflow during rhythmic exercise in humans. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:H2017–H2024. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.6.H2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Seals DR, Mark AL. Differential control of heart rate and sympathetic nerve activity during dynamic exercise. Am J Physiol. 1987;79:508–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI112841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watenpaugh DE, Hargens AR. The cardiovascular system in microgravity. In: Fregly MJ, Blatties CM, editors. Handbook of Physiology, section 4, Environmental Physiology. Vol. 3. Bethesda: American Physiological Society; 1996. pp. 631–666. chap 29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Muller K, Schuber M, Wackerhage H, Hoffmann U, Gunther RW, Adam G, Neuerburg JM, Sinitsyn VE, Bacharev AO, Belichenko OI. Changes in calf muscle performance, energy metabolism, and muscle volume caused by long-term stay on space station MIR. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18(Suppl. 4):308–309. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]