Abstract

Calcium sparks result from the concerted opening of a small number of Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors, RyRs) organized in clusters in the membrane of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). Calcium sparks represent the elementary events of SR Ca2+ release in cardiac myocytes, and their spatial and temporal summation results in whole-cell [Ca2+]i transients observed during excitation–contraction coupling (ECC). Atrial myocytes generally lack transverse tubules; however, during ECC Ca2+ release is initiated from junctional SR (j-SR) in the cell periphery from where activation propagates inwardly through Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from non-junctional SR (nj-SR). Despite the structural differences in the microdomains of RyRs of j-SR and nj-SR, spontaneous Ca2+ sparks are observed from both types of SR, albeit at different frequencies. In cells that showed spontaneous Ca2+ sparks from j-SR and nj-SR, subsarcolemmal (SS) Ca2+ sparks from the j-SR were 3–4 times more frequent than central (CTR) Ca2+ sparks occurring from nj-SR. Subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks had a slightly higher amplitude, but were essentially identical in their spatial spread and duration when compared to CTR Ca2+ sparks. Sensitization of RyRs with a low concentration (0.1 mm) of caffeine led to a 107% increase in the frequency of CTR Ca2+ sparks, whereas the SS Ca2+ spark frequency increased by only 58%, suggesting that the nj-SR is capable of much higher Ca2+ spark activity than observed normally in unstimulated cells. The L-type Ca2+ channel blocker verapamil reduced SS Ca2+ spark frequency to 38% of control values, whereas Ca2+ spark activity from nj-SR was reduced by only 19%, suggesting that SS Ca2+ sparks are under the control of Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space. Removal of extracellular Ca2+ eliminated SS Ca2+ sparks completely, whereas Ca2+ sparks from the nj-SR continued, albeit at a lower frequency. In membrane-permeabilized (saponin-treated) atrial myocytes, where [Ca2+] can be experimentally controlled throughout the entire myocyte, j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ spark frequencies were identical, and Ca2+ sparks could be observed spaced at sarcomeric distances throughout the entire cell, suggesting that all release sites of the nj-SR can become active. Measurement of SR Ca2+ load (10 mm caffeine) revealed no difference between j-SR and nj-SR. The data suggest that in atrial myocytes, which lack a t-tubular system, the nj-SR is fully equipped with a three-dimensional array of functional SR Ca2+ release sites; however, in intact cells under resting conditions, peripheral RyR clusters have a higher probability of activation owing to their association with surface membrane Ca2+ channels, leading to higher spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity. In conclusion, Ca2+ sparks originating from both j-SR and nj-SR are rather stereotypical and show little differences in their spatiotemporal properties. In intact cells, however, the higher frequency of spontaneous SS Ca2+ sparks arises from the structural arrangement of sarcolemma and j-SR membrane and thus from the difference in the trigger mechanism.

Localized non-propagating elementary sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release events, termed Ca2+ sparks (Cheng et al. 1993), result from the activation of individual clusters of ryanodine receptors (RyRs; Lipp & Niggli, 1996; Parker et al. 1996; Blatter et al. 1997; Bridge et al. 1999; Lukyanenko et al. 2000). In ventricular myocytes, which possess an extensive transverse (t)-tubular network, surface membrane voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (or dihydropyridine receptors, DHPRs) are closely associated with RyRs, and Ca2+ sparks have been found to occur in close proximity to t-tubules, reflecting the close contact between DHPRs and RyRs (Shacklock et al. 1995; Cleemann et al. 1998; Tanaka et al. 1998). Consistent with this arrangement, ventricular sparks have relatively uniform characteristics (Cannell et al. 1994, 1995; Lopez-Lopez et al. 1994, 1995).

In contrast to ventricular myocytes, in other cardiac cell types, such as neonatal myocytes, pacemaker cells, atrial myocytes or Purkinje cells the t-tubular system is poorly developed or entirely absent (Huser et al. 1996). In cells lacking t-tubules, two types of SR can be defined, based on their location relative to the surface membrane. Junctional SR (j-SR) is found in the cell periphery, where it is organized in peripheral couplings, i.e. the SR membrane is found in close spatial association with the surface membrane, similar to the diadic cleft in ventricular myocytes (McNutt & Fawcett, 1969; Kockskamper et al. 2001). In contrast, non-junctional SR (nj-SR) is found in deeper regions of the cell and does not associate with the surface membrane. Both j-SR and nj-SR possess RyRs (Carl et al. 1995; Kockskamper et al. 2001; Mackenzie et al. 2001) and have been shown to be capable of active SR Ca2+ release. Nonetheless, the detailed mechanisms that regulate Ca2+ release from nj-SR are still poorly understood, and its relevance to excitation–contraction coupling (ECC) has remained controversial (e.g. Blatter et al. 2003).

Cells lacking t-tubules also show variable spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity. In neonatal cells, where the t-tubular system is still developing, Ca2+ sparks are restricted to the cell periphery and are associated with caveolae (Lohn et al. 2000). In rabbit Purkinje cells, which also lack t-tubules but contain peripheral and central RyRs (Cordeiro et al. 2001), Ca2+ sparks occur only at the cell periphery, even during β-adrenergic stimulation. In contrast, in canine Purkinje cells, Ca2+ sparks occur ubiquitously throughout the cell (Stuyvers et al. 2005). In rat atrial cells, Ca2+ sparks have been observed in the central and subsarcolemmal regions of the myocytes with no significant differences in frequency, amplitude or kinetics (Tanaka et al. 2001). This is in contrast to the finding of ‘eager’ Ca2+ release sites in the periphery of rat atrial myocytes with a high propensity for spontaneous Ca2+ sparks (Mackenzie et al. 2001) and the observation that the vast majority of Ca2+ sparks are associated with sarcolemmal membranes or the irregular internal transverse-axial tubular system (TATS) found in rat atrial cells (Kirk et al. 2003). Furthermore, aside from different frequencies, peripheral and central Ca2+ sparks in rat atrial myocytes have also been found to have differing spatiotemporal characteristics (Woo et al. 2003a), and it has been suggested that the higher frequency of peripheral Ca2+ sparks may result from interactions between the α1C subunit of the DHPR with the RyR (Woo et al. 2003b).

We showed previously (Huser et al. 1996) that in cat atrial myocytes (which completely lack t-tubules) Ca2+ sparks originate from both j-SR and nj-SR, but that spontaneous Ca2+ sparks from j-SR occur at a significantly higher frequency than nj-SR Ca2+ sparks, despite the observation that both the j-SR and nj-SR contain RyR clusters with comparable density and spatial organization (Kockskamper et al. 2001). Thus, the goal of the present study was to determine whether the lower spontaneous Ca2+ spark activity from nj-SR resulted from an intrinsic difference in the Ca2+ release machinery or in the Ca2+ load between j-SR and nj-SR in cat atrial myocytes. A preliminary account of this work has appeared in abstract form (Sheehan & Blatter, 2002).

Methods

Isolation of cat atrial myocytes

Single myocytes were isolated from cat atria as previously described (Wu et al. 1991; Kockskamper & Blatter, 2002; Sheehan & Blatter, 2003). The procedure for cell isolation was fully approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Loyola University Medical Center. Thirty-four hearts were used to isolate atrial myocytes. Briefly, adult mongrel cats of either sex were anaesthetized with thiopentone sodium (35 mg kg−1i.p.). Following thoracotomy, hearts were quickly excised, mounted on a Langendorff apparatus, and retrogradely perfused with oxygenated collagenase-containing solution at 37°C. Cells were plated onto coverslips for later experimentation. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25°C).

Measurements of intracellular calcium

Intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) was measured in intact and permeabilized atrial myocytes with fluorescence laser scanning confocal microscopy. Intact atrial myocytes were loaded with the Ca2+ indicator fluo-4 by 20 min incubation in Tyrode solution containing 20 μm fluo-4 AM (fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester; Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at room temperature. A glass coverslip with the cells was mounted in an experimental chamber on the stage of an inverted microscope. Cells were superfused continuously (1 ml min−1) with normal Tyrode solution (composition, mm: NaCl, 140; KCl, 4; CaCl2, 2; MgCl2, 1; glucose, 10; and Hepes, 10; pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Fifteen to twenty minutes were allowed for de-esterification of the dye. Measurements of [Ca2+]i were performed with laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSM 410; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany; and Radiance 2000 MP, Hertfordshire, Bio-Rad, UK). Fluo-4 was excited with the 488 nm line of an argon ion laser, and fluorescence was measured at wavelengths > 515 nm. Images were acquired in the linescan mode (1.4–3.0 ms per scan; pixel size of 0.1 μm). All linescan images were recorded by placing the scanning line parallel to the longitudinal axis of the cell at a central focal plane.

For experiments in permeabilized cells, the surface membrane was permeabilized by exposure to 0.005% (w/v) saponin (Zima et al. 2003). After 30 s the bath solution was exchanged to a saponin-free internal solution composed of (mm): potassium aspartate, 100; KCl, 15; KH2PO4, 5; MgATP, 5; EGTA, 0.4; CaCl2, 0.12; MgCl2, 0.75; phosphocreatine, 10; creatine phosphokinase, 5 U ml−1; dextran (MW 40 000 Da), 8%; Hepes, 10; and fluo-4 potassium salt, 0.03; pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH. The free [Ca2+] and [Mg2+] of this solution were 100 nm and 1 mm, respectively (calculated using WinMAXC 2.05, Stanford University, CA, USA).

Calcium spark frequencies and characteristics were determined from linescan images using an automated spark detection and quantification algorithm (Cheng et al. 1999; Zima et al. 2004). Calcium sparks were quantified in terms of amplitude (F/F0), full-width at half-maximum amplitude (FWHM, in μm), and duration at half-maximum amplitude (in ms). F0 is the fluoresecence (F) recorded under steady-state conditions at the beginning of an experiment. Calcium spark frequencies are expressed as number of observed sparks per second and per 100 μm of scanned distance (sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1). Prior to the recording of Ca2+ sparks in resting intact myocytes, cells were field-stimulated to elicit action potentials (APs) and to establish uniform SR Ca2+ loading conditions.

Data analysis

Results are reported as means ± s.e.m. for the indicated number (N) of cells or number (n) of Ca2+ sparks. Statistical significance was evaluated using Student's t test.

Results

Characteristics of Ca2+ sparks in intact cat atrial myocytes

We systematically compared the properties of Ca2+ sparks recorded from the subsarcolemmal (SS) j-SR and central(CRT) nj-SR of intact atrial myocytes under control conditions ([Ca2+]o, 2 mm; [Na+]o, 140 mm). Figure 1A shows linescan images of SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks recorded from the same cell. To record SS Ca2+ sparks the scan line was positioned within less than 1 μm from the edge of the cell and orientated parallel to the longitudinal cell axis. In the axial dimension, the focal plane was set at the central depth of the cell, i.e. at an equal distance from the lower and upper cell border. The traces beneath the linescan images represent local changes of [Ca2+]i (F/F0, averaged over a distance of 1 μm) recorded from selected subcellular regions marked by the black squares to the left of the images. As summarized in Table 1, the most striking difference between spontaneous SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks was their frequency of occurrence. Subsarcolemmal Ca2+ sparks were 3–4 times more frequent than CTR sparks (6.6 ± 1.5 versus 1.9 ± 0.5 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1; N = 14 cells; P < 0.005; unpaired t test). The amplitude (F/F0) of CTR Ca2+ sparks was on average about 10% lower compared to SS Ca2+ sparks, whereas spatial width and duration were essentially identical in both regions.

Figure 1. Effect of RyR sensitization on j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ spark frequency in intact atrial mycocytes.

A, confocal linescan images (fluo-4 fluorescence) of Ca2+ sparks in control conditions recorded from the j-SR (SS, top) and nj-SR (CTR, bottom). Below the linescan images are local F/F0 profiles, obtained by averaging fluo-4 fluorescence from 1 μm wide regions indicated by black squares to the left of the images. B, confocal linescan images and local F/F0 profiles of Ca2+ sparks recorded from the j-SR (SS, top) and nj-SR (CTR, bottom) in the presence of 0.1 mm caffeine. C, average Ca2+ spark frequencies under control conditions (Ctl) and in the presence of 0.1 mm caffeine (Caf) in the SS and CTR regions of atrial myocytes. D, relative (%) increase in SS and CTR Ca2+ spark frequencies in the presence of caffeine. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to respective controls; paired t test.

Table 1. The properties of Ca2+ sparks recorded from subsarcolemmal and central regions of intact atrial myocytes.

| Linescan position and SR type | Amplitude (F/F0) | Spatial width (μm) | Duration (ms) | Frequency (sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsarcolemmal, j-SR | 2.16 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.02 | 16.2 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | 647 |

| Central, nj-SR | 1.93 ± 0.03 | 1.22 ± 0.05 | 17.8 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 177 |

A number of possibilities can be envisioned to explain the difference in j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ spark frequency. We addressed the following possibilities experimentally: (1) a fraction of central nj-SR RyR clusters are non-functional (or ‘silent’) under resting conditions; (2) subsarcolemmal release sites are exposed to higher [Ca2+]i owing to stochastic openings of L-type Ca2+ channels; and/or (3) there are differences in j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ load.

Effect of sensitization of RyR to cytosolic Ca2+

We explored whether increasing the sensitivity of the RyR to Ca2+ could activate ‘silent’ RyR clusters in the nj-SR membrane in intact myocytes. For this purpose we used caffeine at a low concentration (0.1 mm), which does not evoke global SR Ca2+ release but substantially sensitizes RyRs to cytosolic Ca2+ and to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. As shown in Fig. 1B, in the presence of caffeine, the frequency of both SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks increased substantially. In this set of experiments (N = 5) Ca2+ spark frequency was measured in the same cells, first under control conditions, followed by exposure to 100 μm caffeine. The average Ca2+ spark frequency increased from 4.1 ± 0.6 to 5.7 ± 0.7 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1 in the SS region, whereas in the CTR region the frequency increased from 1.6 ± 0.3 to 3.0 ± 0.3 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1 (Fig. 1C). Even though the overall absolute SS Ca2+ spark frequency remained higher in the SS space, the relative effect on the nj-SR was significantly more pronounced (Fig. 1D). Within 2 min after addition of caffeine, Ca2+ spark frequency increased on average by only 58 ± 11% (N = 5; P < 0.01) in the SS region of cells, whereas in the cell centre the frequency increased by 107 ± 22% (N = 5; P < 0.05). These data indicate that increasing the sensitivity of RyRs to Ca2+ makes the regional differences in Ca2+ spark activity (j-SR versus nj-SR) significantly less pronounced.

Role of extracellular Ca2+ and Ca2+ influx for Ca2+ spark activation

A key feature of the ultrastructural organization of the j-SR is the close apposition of surface membrane L-type Ca2+ channels (DHPRs) and RyRs in the j-SR membrane (Kockskamper et al. 2001). This arrangement suggests that stochastic openings of DHPRs and the subsequent Ca2+ entry would expose j-SR RyRs to high activating [Ca2+]i more frequently than nj-SR RyRs and therefore could be responsible for the higher propensity of peripheral SS Ca2+ sparks. The following experiments were aimed to determine the role of Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space in Ca2+ spark activation in atrial cells.

In order to investigate the role of Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels in spontaneous Ca2+ spark activation originating from the j-SR and nj-SR of intact atrial myocytes, we used the DHPR inhibitor verapamil (20 μm). Figure 2A shows confocal linescan images of Ca2+ sparks and plots of F/F0 from different subcellular regions under control conditions and after addition of verapamil. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, Ca2+ sparks that originated from the SS region were significantly more sensitive to verapamil treatment than CTR Ca2+ sparks. On average (Fig. 2B), the frequency of SS Ca2+ sparks was reduced by nearly two-thirds to 38 ± 7% of control values (N = 5 cells; P < 0.05), whereas the frequency of CTR Ca2+ sparks decreased by less than 20% (81 ± 11% of control values; N = 5; n.s.). The data suggest that spontaneous openings of L-type Ca2+ channels determine the Ca2+ spark activity from j-SR, but had little influence on the frequency of Ca2+ sparks from nj-SR.

Figure 2. Effect of DHPR blocker verapamil on j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ spark frequency in intact atrial mycocytes.

A, left-hand side, confocal linescan images (fluo-4 fluorescence) and local F/F0 profiles of Ca2+ sparks in control conditions recorded from the j-SR (SS) and nj-SR (CTR). Right-hand side, confocal linescan images and local F/F0 profiles of SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks in the presence of 20 μm verapamil. B, average changes in SS and CTR Ca2+ spark frequency in the presence of verapamil, expressed as percentage Ca2+ spark frequency under control conditions. *P < 0.05 compared to control; paired t-test.

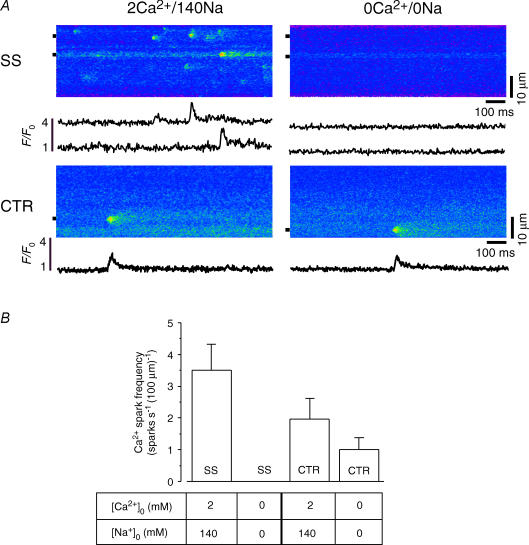

In the next series of experiments, we applied another approach to estimate the role of Ca2+ influx on spontaneous Ca2+ sparks. Cells which exhibited spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in control conditions ([Ca2+]o, 2 mm; [Na]o, 140 nm; 2Ca/140Na bathing solution) were briefly exposed to a nominally Ca2+- and Na+-free Tyrode solution (0Ca/0Na solution). Sodium was removed from the bathing solution to prevent Ca2+ depletion of the SR by sodium–calcium exchange (NCX) during removal of extracellular Ca2+, and it was replaced with equimolar amounts of Li+. Figure 3A shows linescan images and local [Ca2+]i profiles (F/F0) of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks originating from the SS and CTR space. The extracellular solution was then rapidly changed to 0Ca/0Na for 15 s before recording again from the same linescan position. Upon removal of extracellular Ca2+, no further Ca2+ sparks were observed in the SS region (summarized in Fig. 3B). Subsarcolemmal Ca2+ spark activity resumed upon return to 2Ca/140Na but at a lower frequency (not shown). Central Ca2+ sparks showed a very different response to changes in [Ca2+]o. After removal of extracellular Ca2+, spontaneous CTR Ca2+ sparks decreased in frequency from 2.0 ± 0.7 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1 in 2Ca/140Na to 1.0 ± 0.4 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1 in 0Ca/0Na (N = 6 cells), i.e. Ca2+ spark activity was reduced by nearly 50%, but continued in the CTR region throughout the entire period of 0Ca/0Na superfusion, whereas at the same time Ca2+ spark activity in the SS space was abolished. Together these results clearly indicate that Ca2+ entry plays a major role in initiating Ca2+ spark activity from the j-SR, but that nj-SR Ca2+ sparks seem to result from spontaneous openings of RyRs.

Figure 3. Effect of removal of extracellular Ca2+ on j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ spark frequency in intact atrial mycocytes.

A, left-hand side, confocal linescan images (fluo-4 fluorescence) and local F/F0 profiles of Ca2+ sparks in control conditions ([Ca2+]o, 2 mm; [Na]o, 140 nm) recorded from the j-SR (SS) and nj-SR (CTR). Right-hand side, confocal linescan images and local F/F0 profiles of SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks recorded in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ and Na+ (0Ca/0Na). Sodium was replaced by an equimolar amount of Li+. B, average SS and CTR Ca2+ spark frequencies recorded in 2Ca/140Na and 0Ca/0Na.

Role of SR Ca2+ content

Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content is known to influence the frequency and amplitude of Ca2+ sparks (e.g. Satoh et al. 1997; Zima et al. 2004). To determine whether the differences and changes in SS and CTR Ca2+ spark activity in 2Ca/140Na and 0Ca/0Na resulted from differences in Ca2+ load (and changes of it) of the j-SR and the nj-SR, we measured local SR Ca2+ load by challenging intact cells with 10 mm caffeine. For these experiments, the scan line was orientated perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the cell (transverse linescan), which allowed simultaneous visualization of [Ca2+]i in the SS and CTR regions. There was no statistically significant difference in caffeine-releasable SR Ca2+ between these two regions when the cells were rested in 2Ca/140Na. The amplitude (F/F0) of the caffeine-induced [Ca2+]i transient was 9.2 ± 1.9 in the SS space and 8.9 ± 1.9 in the CTR region (N = 10 cells). In 0Ca/0Na, the regional SR load was overall slightly (but not significantly) higher. In 0Ca/0Na, the amplitude of the SS caffeine-induced Ca2+ signal was F/F0 = 10.3 ± 1.2, which was about 10% higher than CTR Ca2+ load (F/F0= 9.2 ± 1.0; N = 14 cells; n.s.). These results indicate that adequate SR Ca2+ was available for release under all experimental conditions, and the significant differences in Ca2+ spark frequency from the j-SR and nj-SR cannot be explained by large regional differences in SR Ca2+ load.

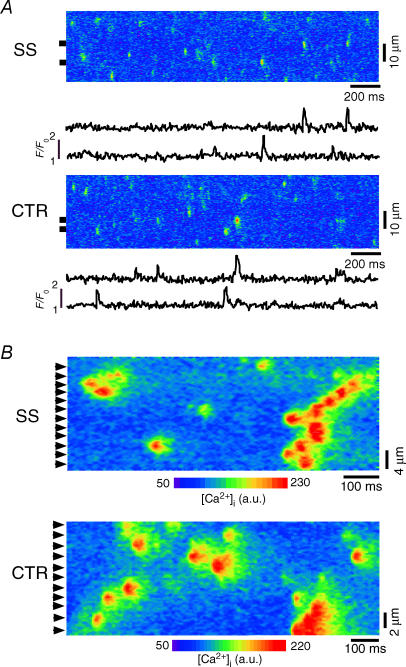

Characteristics of Ca2+ sparks in permeabilized cat atrial myocytes

To eliminate the influence of Ca2+ influx on spontaneous Ca2+ sparks and to gain control of [Ca2+]i surrounding RyRs of both the j-SR and nj-SR we studied Ca2+ sparks in saponin-permeabilized atrial myocytes. This technique allows control of the cytoplasmic milieu regarding its ionic composition (including [Ca2+]), while maintaining the SR structurally and functionally intact (Zima et al. 2003). Figure 4A shows representative confocal linescan images of Ca2+ sparks and plots of F/F0 from SS and CTR regions of an atrial cell after permeabilization of the sarcolemma (free [Ca2+]i, 100 nm). In permeabilized myocytes, the differences between SS and CTR Ca2+ spark frequencies and spatiotemporal characteristics (Table 2) were completely eliminated. On average, the frequencies of SS and CTR Ca2+ sparks were not statistical different, and amounted to 8.5 ± 1.3 and 9.6 ± 0.4 sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1, respectively (N = 10 cells). Figure 4B shows Ca2+ spark sites in SS and CTR regions at higher magnification. It is evident that essentially all j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ release units show Ca2+ spark activity (arrowheads in Fig. 4B). Calcium spark locations were found at regular spatial distances with an average spacing of ∼1.8–2.0 μm, i.e. in an identical spatial pattern that corresponds to the previously determined distribution of RyRs in cat atrial myocytes (Kockskamper et al. 2001). During high Ca2+ spark activity, multifocal Ca2+ sparks (or propagating sparks) spanning over several neighbouring release sites could be observed (Fig. 4B). The data suggest that, under identical activation conditions ([Ca2+]i), spontaneous j-SR and nj-SR Ca2+ sparks are not different in their unitary characteristics and occur at the same frequency. Thus, in cat atrial myocytes, nj-SR RyRs are fully capable of robust Ca2+ release and, in intact cells, the primary difference between spontaneous Ca2+ sparks from the j-SR versus nj-SR is the trigger mechanism. Our data suggest that the DHPR plays a key role in this process and that the close apposition of DHPR and RyRs in the peripheral couplings of the j-SR, together with spontaneous openings of the DHPRs allowing Ca2+ influx, is a key factor for the higher frequency of Ca2+ sparks in the SS space.

Figure 4. Calcium sparks from j-SR and nj-SR in permeabilized atrial mycocytes.

A, confocal linescan images (fluo-4 fluorescence) and local F/F0 profiles of Ca2+ sparks from saponin-permeabilized (0.005%, 30 s) atrial myocytes recorded from j-SR (SS; top) and nj-SR (CTR, bottom). B, longitudinal confocal linescan images recorded from SS and CTR region of the cell. Arrowheads indicate individual release sites at a regular spacing of ∼1.8–2.0 μm.

Table 2. The properties of Ca2+ sparks recorded from subsarcolemmal and central regions of permeabilized atrial myocytes.

| Linescan position and SR type | Amplitude (F/F0) | Spatial width (μm) | Duration (ms) | Frequency (sparks s−1 (100 μm)−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsarcolemmal, j-SR | 1.83 ± 0.02 | 1.68 ± 0.04 | 30.4 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 1.3 | 329 |

| Central, nj-SR | 1.96 ± 0.03 | 1.75 ± 0.04 | 31.5 ± 0.5 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | 379 |

Discussion

In contrast to ventricular myocytes, in atrial cardiac cells of a number of different species the AP-induced [Ca2+]i transient during ECC is spatially inhomogeneous (for review see Blatter et al. 2003). The [Ca2+]i transient begins in the periphery of the myocyte and propagates in a centripetal direction. Thus, the rise of [Ca2+]i in central regions of atrial cells is delayed and often blunted or incomplete (Berlin, 1995; Huser et al. 1996; Cordeiro et al. 2001; Mackenzie et al. 2001; Sheehan & Blatter, 2003; Perez et al. 2005). Nonetheless, there is strong evidence that Ca2+ diffusion from peripheral release sites is not sufficient to account alone for the rise of [Ca2+]i in the centre of atrial myocytes during ECC, and that active Ca2+ release from RyRs of the j-SR makes its contribution (e.g. Sheehan & Blatter, 2003). These spatial and temporal inhomogeneities have been linked to the complete lack or to an only rudimentary and poorly developed t-tubular membrane system. A rapid activation of SR Ca2+ release is routinely found in atrial cells only in the cell periphery, where the j-SR membrane with its RyRs makes close spatial contact with DHPRs in the sarcolemma to form peripheral couplings. Here, it is believed that the mechanism of ECC resembles closely the situation of ventricular myocytes, where Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (DHPRs) triggers calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) from the SR. In contrast, extension of Ca2+ release to deeper regions of atrial myocytes occurs through propagating CICR in a Ca2+ wave-like fashion, although Woo et al. (2002, 2005) described a subpopulation of rat atrial myocytes that revealed a fast Ca2+ current (ICa)-dependent component of central Ca2+ release that resulted in a more synchronized Ca2+ release throughout the cell. Most of the studies on Ca2+ spark frequencies in atrial myocytes (for references see Introduction) have reported significantly lower Ca2+ spark activity from the nj-SR. This reduced Ca2+ spark activity is paralleled by a lower Ca2+ release activity during ECC, resulting in a delayed [Ca2+]i transient with a lower amplitude. Nonetheless, several reports have described conditions in which Ca2+ release from nj-SR can be enhanced, which ultimately lead to a globalization of the Ca2+ signal. Inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ buffering systems (inhibition of the SRCa+ pump or mitochondria) or the application of positive inotropic agonists (endothelin-1, β-adrenergic stimulation) led to the activation of otherwise silent RyRs in the central regions of atrial myocytes (Mackenzie et al. 2004a; Zima & Blatter, 2004; Li et al. 2005). Similar observations were made with caffeine (Mackenzie et al. 2001), the same agent that increased central Ca2+ spark activity in our study (Fig. 1). Interestingly, activation of IP3 receptor-dependent Ca2+ release has a similar effect on the [Ca2+]i transient, together with an overall increase of Ca2+ spark activity (Mackenzie et al. 2002, 2004b; Zima & Blatter, 2004; Li et al. 2005). In addition, we showed that, in permeabilized myocytes where all RyRs are exposed to the same conditions, Ca2+ spark frequencies and properties were identical in the j-SR and the nj-SR. The common conclusions that can be drawn from all these studies are that the nj-SR is well equipped with RyRs (Kockskamper et al. 2001; Mackenzie et al. 2001), that the nj-SR is sufficiently loaded with Ca2+ required for a robust Ca2+ release and that positive inotropic stimuli can globalize SR Ca2+ release throughout the entire atrial myocyte. Under control conditions, however, one has to assume that the mechanism that triggers CICR from nj-SR RyRs is not as efficient as in the cell periphery (j-SR). An obvious reason is the structural arrangement of the peripheral couplings of the j-SR, which resembles both structurally and functionally the diadic cleft of ventricular myocytes. Only small Ca2+ fluxes are required to raise the [Ca2+] in the restricted volume of this microdomain to the micromolar level, which is required for maximal activation of all RyRs in a cluster. Thus, CICR from j-SR is designed to be highly efficient, whereas Ca2+ release from nj-SR appears to have a more dynamic range of regulation. Consistent with different degrees of efficacy of CICR is the observation that SS Ca2+ sparks have a slightly higher amplitude (even though SR Ca2+ load is the same) in intact 0myocytes, whereas in permeabilized cells CTR Ca2+ sparks were slightly larger. The structural arrangement of the j-SR in atrial myocytes may even present a barrier to centripetal Ca2+ diffusion required for CICR from nj-SR and favours lateral diffusion of Ca2+ in the SS space, which can give rise to subsarcolemmal propagation of Ca2+ sparks (Kockskamper et al. 2001).

While many aspects regarding the mechanisms that control central Ca2+ release remain poorly understood, it becomes increasingly clear that nj-SR is fully equipped for robust Ca2+ release; however, the efficacy of Ca2+ release under physiological conditions is relatively low. This allows for a high dynamic range for regulation and adaptation of central Ca2+ release. Central Ca2+ release is responsive to positive inotropic stimuli (Mackenzie et al. 2004a; Li et al. 2005). The unique mechanism underlying the positive inotropic reserve in atrial myocytes consists of an increase of the efficacy of nj-SR Ca2+ release, possibly through recruitment of normally silent RyRs (Mackenzie et al. 2004a), whereas in ventricular myocytes positive inotropic agents act through enhancing Ca2+ release from already active release sites. While atrial contractions contribute relatively little to ventricular filling (preload) and ultimately cardiac output at rest, their contributions and haemodynamic consequences under specific physiological and pathophysiological conditions (Naito et al. 1983; Nishimura et al. 1995; Tada et al. 2002) have been recognized clinically for a long time (Braunwald & Frahm, 1961). For example, sympathetic stimulation during exercise significantly increases atrial contraction and contribution to ventricular filling. Atrial filling fraction increases with age (Kuo et al. 1987) and, in cardiac hypertrophy, where ventricular compliance is reduced, atrial contraction contributes significantly to ventricular filling and cardiac output even at rest. Consequently, loss of effective atrial contraction prevents patients with atrial fibrillation from performing strenuous exercise, impairs ventricular function (Yu et al. 2001), and can lead (together with an irregular and increased ventricular heart rate) to an acute decompensation of an otherwise compensated cardiac disease (Nattel, 2002).

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Joseph G. Akar, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Loyola University Medical Center, for critical discussion and comments. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (HL62231) and the AHA (95002520; 0550170Z) to L.A.B., and from the AHA (0530309Z) and the Potts Estate Loyola University Chicago (RFC 107457) to A.V.Z. K.A.S. was supported by an Arthur J. Schmitt Dissertation Fellowship (Loyola University Chicago) and a Lilly Graduate Student Fellowship in Cardiovascular Research (Loyola University Chicago & Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

References

- Berlin JR. Spatiotemporal changes of Ca2+ during electrically evoked contractions in atrial and ventricular cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1165–H1170. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter LA, Huser J, Rios E. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release flux underlying Ca2+ sparks in cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4176–4181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatter LA, Kockskamper J, Sheehan KA, Zima AV, Huser J, Lipsius SL. Local calcium gradients during excitation–contraction coupling and alternans in atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;546:19–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E, Frahm CJ. Studies on Starling's law of the heart. IV. Observations on the hemodynamic functions of the left atrium in man. Circulation. 1961;24:633–642. [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JH, Ershler PR, Cannell MB. Properties of Ca2+ sparks evoked by action potentials in mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999;518:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0469p.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. Spatial non-uniformities in [Ca2+]i during excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophys J. 1994;67:1942–1956. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80677-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannell MB, Cheng H, Lederer WJ. The control of calcium release in heart muscle. Science. 1995;268:1045–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.7754384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl SL, Felix K, Caswell AH, Brandt NR, Ball WJ, Jr, Vaghy PL, Meissner G, Ferguson DG. Immunolocalization of sarcolemmal dihydropyridine receptor and sarcoplasmic reticular triadin and ryanodine receptor in rabbit ventricle and atrium. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:672–682. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Song LS, Shirokova N, Gonzalez A, Lakatta EG, Rios E, Stern MD. Amplitude distribution of calcium sparks in confocal images: theory and studies with an automatic detection method. Biophys J. 1999;76:606–617. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleemann L, Wang W, Morad M. Two-dimensional confocal images of organization, density, and gating of focal Ca2+ release sites in rat cardiac myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro JM, Spitzer KW, Giles WR, Ershler PE, Cannell MB, Bridge JH. Location of the initiation site of calcium transients and sparks in rabbit heart Purkinje cells. J Physiol. 2001;531:301–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0301i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huser J, Lipsius SL, Blatter LA. Calcium gradients during excitation–contraction coupling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 1996;494:641–651. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk MM, Izu LT, Chen-Izu Y, McCulle SL, Wier WG, Balke CW, Shorofsky SR. Role of the transverse-axial tubule system in generating calcium sparks and calcium transients in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;547:441–451. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockskamper J, Blatter LA. Subcellular Ca2+ alternans represents a novel mechanism for the generation of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;545:65–79. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockskamper J, Sheehan KA, Bare DJ, Lipsius SL, Mignery GA, Blatter LA. Activation and propagation of Ca2+ release during excitation-contraction coupling in atrial myocytes. Biophys J. 2001;81:2590–2605. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75903-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo LC, Quinones MA, Rokey R, Sartori M, Abinader EG, Zoghbi WA. Quantification of atrial contribution to left ventricular filling by pulsed Doppler echocardiography and the effect of age in normal and diseased hearts. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59:1174–1178. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zima AV, Sheikh F, Blatter LA, Chen J. Endothelin-1-induced arrhythmogenic Ca2+ signaling is abolished in atrial myocytes of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate(IP3)-receptor type 2-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2005;96:1274–1281. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000172556.05576.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipp P, Niggli E. A hierarchical concept of cellular and subcellular Ca2+-signalling. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1996;65:265–296. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(96)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohn M, Furstenau M, Sagach V, Elger M, Schulze W, Luft FC, Haller H, Gollasch M. Ignition of calcium sparks in arterial and cardiac muscle through caveolae. Circ Res. 2000;87:1034–1039. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local, stochastic release of Ca2+ in voltage-clamped rat heart cells: visualization with confocal microscopy. J Physiol. 1994;480:21–29. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Lopez JR, Shacklock PS, Balke CW, Wier WG. Local calcium transients triggered by single L-type calcium channel currents in cardiac cells. Science. 1995;268:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7754383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanenko V, Gyorke I, Subramanian S, Smirnov A, Wiesner TF, Gyorke S. Inhibition of Ca2+ sparks by ruthenium red in permeabilized rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys J. 2000;79:1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76381-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Lipp P. Predetermined recruitment of calcium release sites underlies excitation–contraction coupling in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2001;530:417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0417k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Bootman MD, Laine M, Berridge MJ, Thuring J, Holmes A, Li WH, Lipp P. The role of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in Ca2+ signalling and the generation of arrhythmias in rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2002;541:395–409. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Berridge MJ, Conway SJ, Bootman MD. The spatial pattern of atrial cardiomyocyte calcium signalling modulates contraction. J Cell Sci. 2004a;117:6327–6337. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie L, Roderick HL, Proven A, Conway SJ, Bootman MD. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in the heart. Biol Res. 2004b;37:553–557. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNutt NS, Fawcett DW. The ultrastructure of the cat myocardium. II. Atrial muscle. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:46–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M, Dreifus LS, David D, Michelson EL, Mardelli TJ, Kmetzo JJ. Reevaluation of the role of atrial systole to cardiac hemodynamics: evidence for pulmonary venous regurgitation during abnormal atrioventricular sequencing. Am Heart J. 1983;105:295–302. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(83)90530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 2002;415:219–226. doi: 10.1038/415219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura RA, Hayes DL, Holmes DR, Jr, Tajik AJ. Mechanism of hemodynamic improvement by dual chamber pacing for severe left ventricular dysfunction: an acute Doppler and catheterization hemodynamic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:281–288. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00419-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker I, Zang WJ, Wier WG. Ca2+ sparks involving multiple Ca2+ release sites along Z-lines in rat heart cells. J Physiol. 1996;497:31–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CG, Copello JA, Li Y, Karko KL, Gomez L, Ramos-Franco J, Fill M, Escobar AL, Mejia-Alvarez R. Ryanodine receptor function in newborn rat heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2527–H2540. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00188.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh H, Blatter LA, Bers DM. Effects of [Ca2+]i, SR Ca2+ load, and rest on Ca2+ spark frequency in ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H657–H668. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.2.H657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacklock PS, Wier WG, Balke CW. Local Ca2+ transients (Ca2+ sparks) originate at transverse tubules in rat heart cells. J Physiol. 1995;487:601–608. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan KA, Blatter LA. Initiation mechanism amd frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ sparks in atrial myocytes. Biophys J. 2002;82:281a. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan KA, Blatter LA. Regulation of junctional and non-junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in excitation–contraction coupling in cat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;546:119–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuyvers BD, Dun W, Matkovich S, Sorrentino V, Boyden PA, Ter Keurs HE. Ca2+ sparks and waves in canine purkinje cells: a triple layered system of Ca2+ activation. Circ Res. 2005;97:35–43. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173375.26489.fe. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tada T, Oki T, Abe M, Yamada H, Matsuoka M, Yamamoto T, Tabata T, Wakatsuki T, Ito S. The role of short- and long-axis function in determining late diastolic left ventricular filling in patients with hypertension: assessment by pulsed Doppler tissue imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:1211–1217. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.124007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Masumiya H, Sekine T, Kase J, Kawanishi T, Hayakawa T, Miyata S, Sato Y, Nakamura R, Shigenobu K. Involvement of Ca2+ waves in excitation-contraction coupling of rat atrial cardiomyocytes. Life Sci. 2001;70:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Sekine T, Kawanishi T, Nakamura R, Shigenobu K. Intrasarcomere [Ca2+] gradients and their spatio-temporal relation to Ca2+ sparks in rat cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 1998;508:145–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.145br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CM, Wang Q, Lau CP, Tse HF, Leung SK, Lee KL, Tsang V, Ayers G. Reversible impairment of left and right ventricular systolic and diastolic function during short-lasting atrial fibrillation in patients with an implantable atrial defibrillator: a tissue Doppler imaging study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:979–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SH, Cleemann L, Morad M. Ca2+ current-gated focal and local Ca2+ release in rat atrial myocytes: evidence from rapid 2-D confocal imaging. J Physiol. 2002;543:439–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SH, Cleemann L, Morad M. Spatiotemporal characteristics of junctional and nonjunctional focal Ca2+ release in rat atrial myocytes. Circ Res. 2003a;92:e1–e11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000051887.97625.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SH, Cleemann L, Morad M. Diversity of atrial local Ca2+ signalling: evidence from 2-D confocal imaging in Ca2+-buffered rat atrial myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;567:905–921. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo SH, Soldatov NM, Morad M. Modulation of Ca2+ signalling in rat atrial myocytes: possible role of the α1C carboxyl terminal. J Physiol. 2003b;552:437–447. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.048330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Vereecke J, Carmeliet E, Lipsius SL. Ionic currents activated during hyperpolarization of single right atrial myocytes from cat heart. Circ Res. 1991;68:1059–1069. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.4.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima AV, Blatter LA. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent Ca2+ signalling in cat atrial excitation–contraction coupling and arrhythmias. J Physiol. 2004;555:607–615. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.058529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima AV, Copello JA, Blatter LA. Effects of cytosolic NADH/NAD+ levels on sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in permeabilized rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 2004;555:727–741. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zima AV, Kockskamper J, Mejia-Alvarez R, Blatter LA. Pyruvate modulates cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release in rats via mitochondria-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Physiol. 2003;550:765–783. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]