Abstract

FoxD3 is a forkhead-related transcriptional regulator that is essential for multiple developmental processes in the vertebrate embryo, including neural crest development and maintenance of mammalian stem cell lineages. Recent results demonstrate a requirement for FoxD3 in Xenopus mesodermal development. In the gastrula, FoxD3 functions as a transcriptional repressor in the Spemann organizer to maintain the expression of Nodal-related members of the TGFß superfamily that induce dorsal mesoderm formation. Here we report that the function of FoxD3 in mesoderm induction is dependent on the recruitment of transcriptional corepressors of the TLE/Groucho family. Structure-function analyses indicate that the transcriptional repression and mesoderm induction activities of FoxD3 are dependent on a C-terminal domain, as well as specific DNA-binding activity conferred by the forkhead domain. The C-terminal domain contains a heptapeptide similar to the eh1/GEH Groucho interaction motif. Deletion and point mutagenesis demonstrated that the FoxD3 eh1/GEH motif is required for both repression of transcription and induction of mesoderm, as well as the direct physical interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4 (Groucho-related gene-4). Consistent with a functional interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4, the transcriptional repression activity of FoxD3 is enhanced by Grg4, and reduced by Grg5, a dominant inhibitory Groucho protein. The results indicate that FoxD3 recruitment of Groucho corepressors is essential for the transcriptional repression of target genes and induction of mesoderm in Xenopus.

The Fox gene family is a diverse group of forkhead-related transcriptional regulators, many of which play essential roles in metazoan embryogenesis and physiology (1–3). FoxD3 is required for multiple developmental processes in the vertebrate embryo, including neural crest development and maintenance of mammalian stem cell lineages. In Xenopus, zebrafish, chick and mouse, FoxD3 orthologs are expressed in pre-migratory and migrating neural crest cells (4–12), and functional studies indicate that FoxD3 regulates the determination, migration, and/or differentiation of neural crest lineages (13–20). FoxD3 is also expressed in the preimplantation mouse embryo, as well as mammalian embryonic and trophoblast stem cells (9,21–23). FoxD3 null embryos do not form a primitive streak, fail to undergo gastrulation or form mesoderm, and die by 6.5 dpc with greatly reduced epiblast cell number (21). Extraembryonic defects are also observed in FoxD3 nulls due to a failure of trophoblast progenitors to self-renew and differentiate (23). Furthermore, embryonic and trophoblast stem cell lines cannot be established from FoxD3 null embryos (21,23). This requirement for FoxD3 in multiple progenitor populations, including embryonic stem cells, trophoblast stem cells, and possibly neural crest stem cells, suggests that FoxD3 may play a conserved role in maintaining cellular multipotency. Whether FoxD3 has similar transcriptional activity and target genes in these distinct progenitor populations remains to be determined.

In the Xenopus gastrula, FoxD3 is expressed in the Spemann organizer (17,18,24), a signaling center that controls germ layer patterning, morphogenesis and axis formation (25–27). Organizer-restricted expression of FoxD3 is conserved in the zebrafish shield and the chick Hensen’s node, while in the mouse, FoxD3 is expressed throughout the gastrula, including the node (8,10,21). In cells of the organizer, FoxD3 is coexpressed with a variety of developmentally important genes, including Nodal-related members of the TGFß superfamily that are essential for the induction and patterning of dorsal mesoderm (28,29). Recently, we found that FoxD3 is essential in the Xenopus gastrula for dorsal mesodermal development, and subsequent formation of the body axis (30). FoxD3 is necessary for the maintenance of Nodal expression in the organizer, and is sufficient for induction of ectopic Nodal expression outside of the organizer. Consistent with a regulatory interaction of FoxD3 with the Nodal pathway, mesoderm induction in response to FoxD3 gain-of-function was dependent on Nodal, and the developmental defects resulting from FoxD3 knockdown were rescued by activation of Nodal signaling. These studies indicate that FoxD3 function is required in the Spemann organizer to maintain Nodal expression, thus promoting dorsal mesoderm induction and axis formation in Xenopus.

Interestingly, a fusion protein containing the Engrailed repression domain and the FoxD3 DNA-binding domain mimicked the mesoderm inducing activity of FoxD3, while a VP16 activator fusion protein did not (30). These experiments indicate that FoxD3 functions as a transcriptional repressor to maintain Nodal expression and induce mesoderm, suggesting that FoxD3 promotes Nodal expression in the Spemann organizer by repressing a negative regulator of Nodal. The conclusion that FoxD3 functions as a transcriptional repressor in Xenopus mesodermal development is consistent with the repression function of FoxD3 observed in previous cell culture and neural crest studies (9,17,18,31). The mechanisms of transcriptional repression by FoxD3, including the identification of functional domains and transcriptional cofactors, are yet to be determined in any system.

Multiple developmentally important transcriptional regulators repress target gene transcription via interactions with Groucho family corepressors. Groucho proteins are widely expressed, non-DNA-binding transcriptional repressors that are recruited to regulatory sites by specific DNA-binding proteins through conserved protein interaction motifs (32–35). At target promoters, Groucho corepressors recruit Rpd3-related class I histone deacetylases that generate a closed chromatin conformation, preventing transcriptional initiation (33,36). A number of transcriptional regulatory proteins have been identified in Drosophila that recruit Groucho to repress transcription during development, including the bHLH protein Hairy, the homeodomain protein Engrailed, and the NF-κB-related protein Dorsal, which regulate neurogenesis, segment polarity, and dorsal-ventral patterning, respectively (37–41). In Xenopus, two Groucho family genes, Grg4 and Grg5, are ubiquitously expressed during early embryogenesis (42). Grg4 is a functional transcriptional corepressor, while Grg5 lacks several essential domains and functions as a dominant inhibitory Groucho (43). Similar to Drosophila Groucho, Xenopus Groucho-related proteins have been shown to interact with Hairy1, Six1 and Tcf3 to regulate myogenesis, neurogenesis and dorsal determination, along with other developmental regulators (43–45). Identifying additional DNA-binding proteins that interact with Groucho to mediate target gene repression is important for further defining the essential developmental functions of Groucho corepressors.

Here we report the results of mechanistic studies that identify the functional domains and cofactors mediating the transcriptional and developmental functions of FoxD3. The transcriptional repression and mesoderm induction activities of FoxD3 require DNA-binding specificity conferred by the forkhead domain, and the transcriptional repression function of a C-terminal domain containing a heptapeptide sequence similar to the eh1/GEH Groucho interaction motif. This eh1/GEH motif is essential for both the transcriptional repression and mesoderm induction activities of FoxD3, and for the direct physical interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4. In support of a functional interaction of FoxD3 and Groucho corepressors, Grg4 synergistically enhanced, and Grg5 inhibited the transcriptional repression activity of FoxD3. The results establish a molecular mechanism for the transcriptional and developmental functions of FoxD3.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Embryos and Microinjection

Xenopus embryos were collected, fertilized, injected and cultured, and animal pole explants prepared and cultured as previously described (46). Embryonic stage was determined according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (47). Capped, in vitro transcribed mRNA for microinjection was synthesized from linearized DNA templates using the SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion) and 10 nl of RNA solution was injected per embryo. For examination of the subcellular localization of FoxD3-GFP fusion proteins, animal pole explants were dissociated in calcium-free medium as described (48), and individual cells were viewed using Nomarski optics and fluorescence microscopy.

FoxD3 and Groucho Expression Constructs

The FoxD3 constructs described in this study were generated using the pCS2+, pCS2-NLS, pCS2-eGFP, pCS2-Gal4DBD, or pCS2-GST vectors (49) (and this study). A previously described pCS2-FoxD3 subclone containing the open reading frame (nucleotides 172-1287) of Xenopus FoxD3 was used to generate the constructs used in this study (30). These constructs include pCS2-FoxD3AA(N140A/H144A), pCS2-FoxD3-FoxH1WH, pCS2-NLS-FoxD3WH(415-783), pCS2-NLS-FoxD3ΔN(361-1287), pCS2-NLS-FoxD3ΔC(172-819), pCS2-FoxD3F>E(F297E), pCS2-FoxD3A6(GEH>A6), pCS2-FoxD3ΔGEH(172-1062), pCS2-FoxD3-GFP, pCS2-FoxD3AA-GFP, pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3(172-1287), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3AA(N140A/H144A), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3N(172-408), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3C(751-1287), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3C-F>E(F297E), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3C-A6(GEH>A6), pCS2-Gal4DBD-FoxD3C-ΔGEH(751-1062), pCS2-GST-FoxD3(172-1287), pCS2-GST-FoxD3C(751-1287), pCS2-GST-FoxD3C-F>E(F297E), pCS2-GST-FoxD3C-A6(GEH>A6), and pCS2-GST-FoxD3C-ΔGEH(751-1062). A PCR-based approach was used to generate mutations within the FoxD3 DNA-binding domain (pCS2-FoxD3AA) and eh1/GEH domain (pCS2-FoxD3F>E and pCS2-FoxD3A6). For each mutagenesis, pCS2-FoxD3 plasmid was used as template for outward-directed PCR using overlapping primers encoding the mutated sequence. Wild-type plasmid DNA was removed by DpnI digestion of the methylated template DNA, and the amplification products were then ligated and transformed into XL1-Blue. The introduced mutations and the integrity of the open reading frames were verified by sequencing and in vitro translation. A detailed description of the Xenopus FoxD3 constructs used in this study is available on request. Grg4 and Grg5 mRNAs were synthesized from pGlo-myc-Grg4 and pGlo-myc-Grg5 (43).

Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNA was isolated using the RNAqueous kit (Ambion), and cDNA synthesis and PCR were performed as described (48). Radiolabeled PCR products were resolved on 5% native polyacrylamide gels. PCR primers and amplification conditions were as described for EF1α, Muscle Actin (48) and Collagen Type II (50).

Gal4-UAS-Luciferase Reporter Transcriptional Assays

Xenopus embryos were injected in the animal pole at the one-cell stage with in vitro transcribed RNA encoding the Gal4 DNA-binding domain or Gal4-FoxD3 fusion proteins. At the two-cell stage, one blastomere was injected with 100 pg of pGL3-5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase (Firefly luciferase under the control of five Gal4-binding sites and the –104 Goosecoid minimal promoter) in combination with 10 pg of pGL3-CMV-Renilla internal control (Renilla luciferase under the control of the constitutive CMV promoter). Animal pole explants prepared at the midblastula stage were collected at the midgastrula stage and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Promega) and a TD-20/20 luminometer (Turner Designs). The data presented are the results of at least three independent experiments, with error bars representing standard error. A two-tailed student’s T-Test was used to calculate p values.

Protein Interaction Assays and Western Blotting Analysis

One-cell stage embryos were injected with in vitro transcribed RNA encoding glutathione-S-transferase (GST), or GST-FoxD3 fusions proteins alone, or in combination with myc-Grg4 mRNA (43). Embryos collected at the midgastrula stage were homogenized at 4°C in interaction buffer (40mM Hepes pH 7.5, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1% NP40, and 1X Roche protease inhibitor mixture). Cleared supernantants were incubated with an equal volume of a 50% suspension of glutathione-coupled sepharose beads (Amersham) at 4°C for 1 hour with gentle agitation. Beads recovered by low speed spin were washed in 25 volumes of interaction buffer and bound proteins were eluted with SDS-sample buffer at 95°C for 5 minutes. Cleared supernatants and bead eluates were subjected to Western blot analysis using a 1:1000 dilution of anti-GST polyclonal antibody (Amersham) or anti-Myc monoclonal antibody (Sigma), and detected with a 1:3000 dilution of peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody by chemiluminescence (Amersham). For standard Western analysis, embryos were lysed (10 kl per embryo) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) supplemented with protease inhibitors, extracts were cleared by centrifugation, and half an embryo equivalent was loaded per well. An anti-Gal4DBD polyclonal antibody (Sigma) was used at a 1:1000 dilution or an anti-FoxD3 polyclonal antibody (23,30) was used at a 1:200 dilution, and was detected with a 1:3000 dilution of peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody by chemiluminescence (Amersham). As a loading control, duplicate blots were analyzed with a monoclonal antibody against the ubiquitous hnRNPK at a 1:1000 dilution (51).

RESULTS

FoxD3 Mesoderm Induction is Dependent on the Specific DNA-Binding Activity of the Forkhead Domain

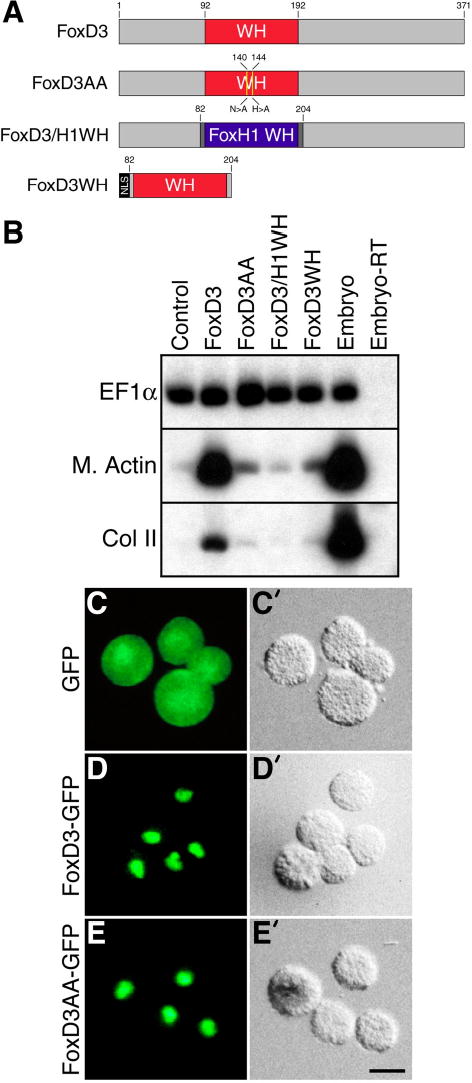

Fox family proteins are characterized by a conserved 100 residue forkhead domain that is required for DNA-binding activity (1,52). FoxD3 orthologs contain a highly conserved, centrally positioned forkhead/winged-helix (WH) domain (residues 92–192 in Xenopus FoxD3), and regions N-terminal and C-terminal to the WH domain are less well conserved and lack previously identified functional motifs (Fig. 1A). It is predicted that mesoderm induction by FoxD3 is dependent on sequence-specific DNA-binding activity conferred by the WH domain. To examine the requirement for FoxD3 DNA-binding activity in mesoderm induction, two highly conserved DNA contact residues of the WH domain were replaced with Alanine (N140A/H144A), a pair of mutations previously shown to ablate the DNA-binding activity of Fox proteins (Fig. 1A) (53,54). The mesoderm-inducing activity of this mutated FoxD3 protein (FoxD3AA) was examined in animal pole explants. At the one-cell stage, RNA encoding native FoxD3 or FoxD3AA (100 pg) was injected into the animal pole, and explants prepared at the blastula stage were collected at the tailbud stage for RT-PCR analysis of mesoderm induction (Fig 1B). While native FoxD3 strongly induced the expression of Muscle Actin (somites) and Collagen II (notochord), FoxD3AA had greatly reduced activity at equal or higher doses (100–500 pg), demonstrating the importance of DNA-binding activity for mesoderm induction by FoxD3. To determine whether sequence-specificity of DNA-binding by the FoxD3 WH domain is essential for mesoderm induction, the FoxD3 WH domain was replaced with the WH domain of FoxH1, another Fox protein involved in mesodermal development that has a distinct DNA-binding sequence specificity (13,55) (Fig. 1A). In the animal pole explant assay, this WH swap protein (FoxD3/H1WH) failed to induce mesoderm, indicating that the sequence specificity of DNA-binding conferred by the FoxD3 WH domain is required for mesoderm induction (Fig. 1B). In addition, the FoxD3 WH domain alone (residues 82-204 fused to a nuclear localization signal) did not induce mesoderm, indicating that the WH domain does not have intrinsic mesoderm induction activity (Fig. 1A,B). For each of the modified forms of FoxD3 (FoxD3AA, FoxD3/H1WH and FoxD3WH), protein products were examined by in vitro translation and expression in embryos to confirm the integrity of the open reading frames and stability of the proteins (data not shown). The results indicate that mesoderm induction by FoxD3 is dependent on sequence-specific DNA-binding activity conferred by the WH domain and additional functional domains located either N-terminal or C-terminal to the WH domain.

FIGURE 1. Mesoderm induction by FoxD3 is dependent on the DNA-binding domain.

A, Schematic showing the domain structure full-length FoxD3, a WH domain mutant (FoxD3AA) containing two point mutations (N140A and H144A), a WH domain swap mutant (FoxD3/H1WH) containing the WH domain of FoxH1, and a WH domain only form of FoxD3 lacking N-terminal and C-terminal sequences (FoxD3WH). NLS, nuclear localization signal. B, The indicated mRNAs were injected (300 pg) into the animal pole of one-cell stage embryos, and animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were analyzed by RT-PCR at the tailbud stage for the expression of muscle actin (M. Actin) and collagen II (Col II). Animal explants of uninjected embryos (Control), intact embryos (Embryo) and an identical reaction without reverse transcriptase (Embryo-RT) served as controls for RT-PCR. EF1α is a control for RNA recovery and loading. Panels C–E’, The subcellular localization of GFP (C,C’), FoxD3-GFP (D,D’), and FoxD3AA-GFP (E,E’) was examined in cells of dissociated animal explants by fluorescence (C–E) and DIC (C’–E’) microscopy. For each sample, at least 100 cells were examined and nearly all cells (>95%) displayed the indicated localization pattern. Scale bar, 10μm.

To assess the subcellular localization of FoxD3 and the FoxD3 WH mutant, fusion proteins containing green fluorescent protein were generated. At the one-cell stage, RNA encoding FoxD3-GFP, FoxD3AA-GFP or GFP was injected into the animal pole, explants prepared at the late blastula stage were dissociated in calcium-free medium, and protein localization was examined in individual cells by Nomarski and fluorescence microscopy. While GFP protein was distributed throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm, FoxD3-GFP and the FoxD3AA-GFP were concentrated in the nuclear compartment (Fig. 1C-E). Similarly, FoxD3/H1WH and FoxD3WH were also localized to the nucleus (data not shown). When tested for the ability to induce mesoderm, the activity of FoxD3-GFP was identical to native FoxD3, while FoxD3AA-GFP did not induce mesoderm (data not shown). Therefore, exogenous FoxD3 is localized to the nucleus of cells competent to form mesoderm in response to FoxD3. Furthermore, the results confirm that the lack of activity for FoxD3AA, FoxD3/H1WH and FoxD3WH is not due to protein mislocalization.

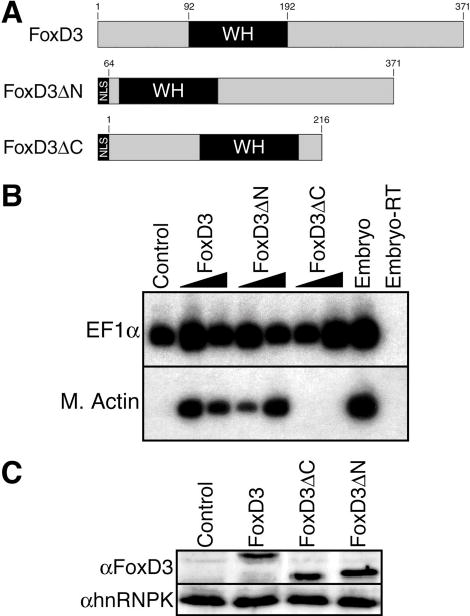

The C-Terminus of FoxD3 is Required for Mesoderm Induction and Transcriptional Repression

To identify additional functional domains required for FoxD3 mesoderm induction, deletion mutants lacking sequences N-terminal (FoxD3ΔN) or C-terminal (FoxD3ΔC) to the WH domain were generated and tested (Fig. 2A). Native FoxD3, FoxD3ΔN, or FoxD3ΔC were expressed in animal pole explants at low (100 pg) or high (300 pg) dose to assess mesoderm-inducing activity. Induction of Muscle Actin at the tailbud stage indicated that the activity of FoxD3ΔN was similar to native FoxD3, while FoxD3ΔC did not induce mesoderm at either dose (Fig. 2B). Consistent with the induction of Muscle Actin, convergent extension of explants, a morphogenetic movement indicative of dorsal mesoderm induction, was observed in response to native FoxD3 and FoxD3ΔN, but not FoxD3ΔC (data not shown). Equal expression of all three proteins was verified by Western blot analysis of injected embryos using a polyclonal antibody to FoxD3 (23,30) (Fig. 2C). Therefore, the region of FoxD3 C-terminal to the WH domain contains a functional domain essential for mesoderm induction.

FIGURE 2. The C-terminal domain of FoxD3 is required for mesoderm induction.

A, Schematic showing full-length FoxD3 and deletion mutants lacking the N-terminal domain (FoxD3ΔN) or the C-terminal domain (FoxD3ΔC). NLS, nuclear localization signal. B, Low or high (100 pg or 300 pg) doses of the indicated mRNAs were injected into the animal pole of one-cell stage embryos, and animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were analyzed by RT-PCR at the tailbud stage for the expression of muscle actin (M. Actin). RT-PCR controls were as described in Fig. 1. C, Extracts prepared from embryos injected with the indicated mRNAs were analyzed by western blotting using an anti-FoxD3 polyclonal antibody to confirm equal expression levels of FoxD3 and the FoxD3 deletion mutants. Duplicate blots were analyzed with an anti-hnRNPK monoclonal antibody to confirm equal protein loading.

Previous analyses of FoxD3 fusion proteins containing the Engrailed repressor domain or the VP16 activator domain indicated that FoxD3 functions as a transcriptional repressor to induce mesoderm in Xenopus (30). To directly assess the transcriptional activity of FoxD3 in Xenopus, and to further define the function of the N-terminal and C-terminal domains, a Gal4-UAS transcriptional reporter system was used. The entire FoxD3 coding region, or the regions N-terminal or C-terminal to the WH domain were fused to the heterologous DNA-binding domain of the yeast transcriptional regulator Gal4 (Fig. 3A). The transcriptional activity of the Gal4 fusion proteins was assayed in animal pole explants using a 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase reporter in which Firefly luciferase is under the control of five copies of the Gal4 binding site and the Goosecoid minimal promoter. RNAs encoding Gal4-FoxD3 fusions proteins, or the Gal4 DNA-binding domain alone were injected at the one-cell stage, a mixture of 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase and internal control CMV-Renilla plasmids was injected at the two-cell stage, and animal pole explants were assayed for luciferase activity at the midgastrula stage. The 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase reporter has a significant and reproducible basal activity in animal pole explants, which permits an assessment of transcriptional repression activity without the addition of activating signals (Fig. 3B and data not shown). The Gal4 DNA-binding domain alone had no effect on basal level transcription, but a Gal4 fusion protein containing the full FoxD3 sequence strongly repressed transcription, resulting in an ~16-fold reduction of luciferase activity (Fig. 3B). The Gal4 fusion protein containing only C-terminal sequences of FoxD3 (residues 194-371) resulted in a much greater degree of transcriptional repression (~240-fold reduction of luciferase activity), while the N-terminal fusion protein (residues 1–79) had nearly no effect (~2-fold reduction) (Fig. 3B). The dramatic difference in the repression activity of the full-length and C-terminal fusion proteins is likely due to the presence of two DNA-binding domains (Gal4 and FoxD3) in the full-length fusion protein, perhaps resulting in competition of endogenous FoxD3-binding sites with the Gal4-binding sites of the reporter. In support of this idea, when the WH domain of full-length Gal4-FoxD3 fusion was mutated (N140A/H144A) to inactivate DNA binding, as described above, the repression activity of Gal4-FoxD3AA (~220-fold reduction of luciferase activity) was nearly as strong as the C-terminal fusion protein (data not shown). Equal expression of each of the Gal4-FoxD3 proteins was verified by Western blot analysis of injected embryos using a polyclonal antibody to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (data not shown). Taken together, these experiments indicate that the C-terminal region of FoxD3 is essential for both transcriptional repression and mesoderm induction activities.

FIGURE 3. A C-terminal transcriptional repression domain of FoxD3.

A, Schematic showing fusion proteins containing the Gal4 DNA-binding domain and full-length FoxD3, or the N-terminal or C-terminal domains of FoxD3. B, To determine the transcriptional activity of the Gal4-FoxD3 fusion proteins, the indicated mRNAs (300 pg) were injected into the animal pole at the one-cell stage, and at the two-cell stage a mixture of 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase (100 pg) and CMV-Renilla Luciferase (10 pg) DNAs was injected. The Gal4 DNA-binding domain alone (Gal4) was used as a negative control. Animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were assayed for luciferase activity at the midgastrula stage. Values shown are normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and represent fold repression of basal reporter activity in the absence of injected mRNAs (Control). The mean and standard error for four independent experiments is presented. Statistical significance was assessed using the student’s t-TEST (*, p<0.05).

FoxD3 Contains an Eh1/GEH Motif that is Required for Mesoderm Induction and Transcriptional Repression

To identify the functional domains present in the C-terminal region of FoxD3, we first carried out a comparative analysis of the FoxD3 orthologs to identify conserved sequences within the C-terminal region. Sequence alignment (ClustalW, MacVector 7.2) of Xenopus, zebrafish, chick, mouse and human FoxD3 proteins identified a perfectly conserved heptapeptide (residues 297-303 of Xenopus FoxD3) (Table 1), and this high degree of conservation suggests functional importance. Comparison of the FoxD3 heptapeptide (FSIENII) with known transcriptional repression motifs in the NCBI database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) revealed high similarity to the eh1/GEH motif (FSIDNIL) (56). The eh1/GEH motif (Engrailed homology region-1/Goosecoid-Engrailed homology) is an active repression domain, first identified in the Drosophila Engrailed protein (56), that mediates direct physical interaction with Groucho family transcriptional corepressors (32–35). The presence of an absolutely conserved Groucho interaction motif within the C-terminal functional domain of FoxD3 suggests that Groucho corepressors may be recruited by FoxD3 to repress transcription and induce mesoderm.

TABLE 1.

FoxD3 Orthologs Contain a Conserved Groucho-Interaction Motif

| Gene | Sequence | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| Xenopus FoxD3 | 297-FSIENII-303 | AB014611 |

| Zebrafish FoxD3 | 297-FSIENII-303 | BC095603 |

| Chick FoxD3 | 319-FSIENII-325 | U37274 |

| Mouse FoxD3 | 362-FSIENII-368 | AF067421 |

| Human FoxD3 | 378-FSIENII-384 | AF197560 |

| GEH Consensus | FSIDNIL |

A comparison of FoxD3 amino acid sequences from frog, fish, chick, mouse and human othologs reveals absolute conservation of the eh1/GEH motif in the C-terminus. The GEH consensus is based on sequences from Goosecoid, Engrailed and Nkx proteins among others (56).

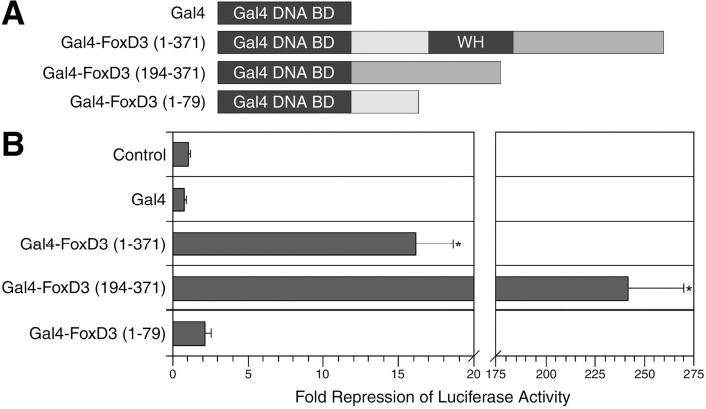

To determine if the eh1/GEH motif is required for FoxD3 function, the motif was mutated or deleted. Three FoxD3 GEH mutants were generated: FoxD3F>E contains a substitution of glutamate for phenylalanine 297 (ESIENII), a residue absolutely conserved in all eh1/GEH motifs (32,34), FoxD3A6 contains alanine substitutions for six of the seven motif residues (AAAAAAI), and FoxD3 (1-296) has a deletion of the GEH motif and sequences C-terminal to the motif (Fig. 4A). The mesoderm-inducing activity of the FoxD3 GEH mutants was examined in animal pole explants, as described above. Analysis of Muscle Actin and Collagen II expression at the tailbud stage indicated that mutation or deletion of the FoxD3 GEH motif resulted in a complete loss of mesoderm induction activity (Fig. 4B). The observation that a single amino acid change in the GEH motif (FoxD3F>E) results in a total loss of mesoderm-inducing activity indicates that the eh1/GEH motif plays an essential role in FoxD3 function.

FIGURE 4. An eh1/GEH motif is required for FoxD3 mesoderm induction and transcriptional repression.

A, Schematic showing wild-type FoxD3 with the location and sequence of the GEH motif indicated, single and multiple point mutants in the GEH domain (FoxD3F>E and FoxD3A6), and a deletion mutant lacking the C-terminal domain that includes the GEH motif (FoxD3 (1-296)). B, The indicated mRNAs (100 pg) were injected into the animal pole of one-cell stage embryos, and animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were analyzed by RT-PCR at the tailbud stage for the expression of muscle actin (M. Actin) and collagen II (Col II). RT-PCR controls were as described in Fig. 1. C, To determine the transcriptional activity of Gal4-FoxD3 fusion proteins with mutation or deletion of the GEH motif, the indicated mRNAs (300 pg) were injected into the animal pole at the one-cell stage, and at the two-cell stage a mixture of 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase (100 pg) and CMV-Renilla Luciferase (10 pg) DNAs was injected. The Gal4 DNA-binding domain alone was used as a negative control. Animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were assayed for luciferase activity at the midgastrula stage. Values shown are normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and represent fold repression of basal reporter activity in the absence of injected mRNAs. The mean and standard error for three independent experiments is presented. Statistical significance was assessed using the student’s t-TEST (*, p<0.05).

The requirement for the eh1/GEH motif in FoxD3 mesoderm induction strongly predicts that the eh1/GEH motif is also required for transcriptional repression by FoxD3. To examine the role of the eh1/GEH motif in the transcriptional activity of FoxD3, Gal4 fusion proteins were generated with the FoxD3 C-terminal region that included the single residue GEH mutation, the six residue GEH mutation, or the GEH deletion (Fig. 4C). The transcriptional activity of the Gal4 fusion proteins was tested using the 5xUAS-Gsc-luciferase reporter as described above. While a Gal4 fusion protein containing the wild-type C-terminal sequences of FoxD3 strongly repressed transcription (146-fold reduction of luciferase activity), mutation or deletion of the GEH motif resulted in dramatic loss of repression activity (~6-fold reduction of luciferase activity) (Fig. 4C). Equal expression of the FoxD3 GEH mutants, either as full-length proteins or Gal4 fusion proteins, was confirmed by western blot analysis of embryo extracts using anti-FoxD3 or anti-Gal4 antibodies (data not shown). Therefore, the transcriptional repression activity of FoxD3 is dependent on the eh1/GEH motif, arguing for the recruitment of Groucho corepressors for FoxD3 function. It should be noted, however, that residual repressor activity is still present (Fig. 4C), although this activity is not sufficient for mesoderm induction (Fig. 4B). Given the absence of additional conserved repression motifs in the C-terminal region, the residual repression activity of the GEH mutants suggests that a cryptic weak repression domain may be present.

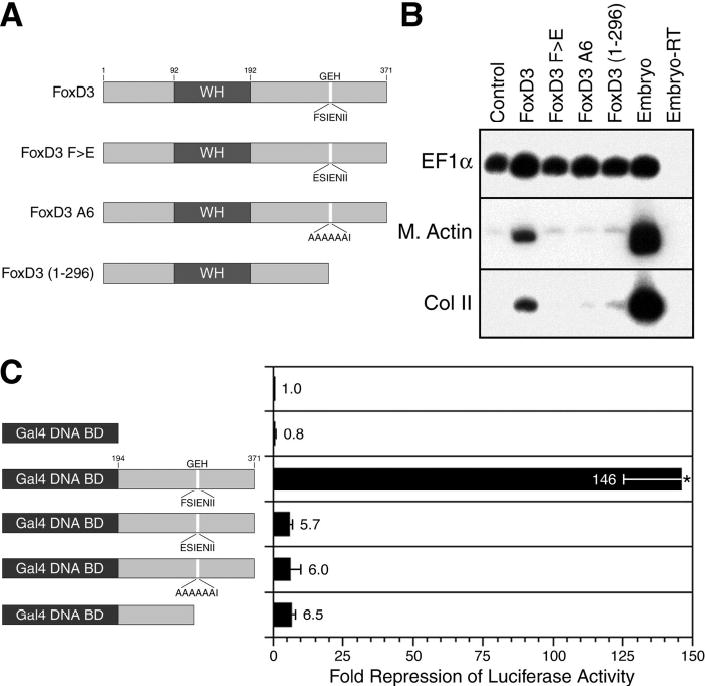

Physical and Functional Interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4

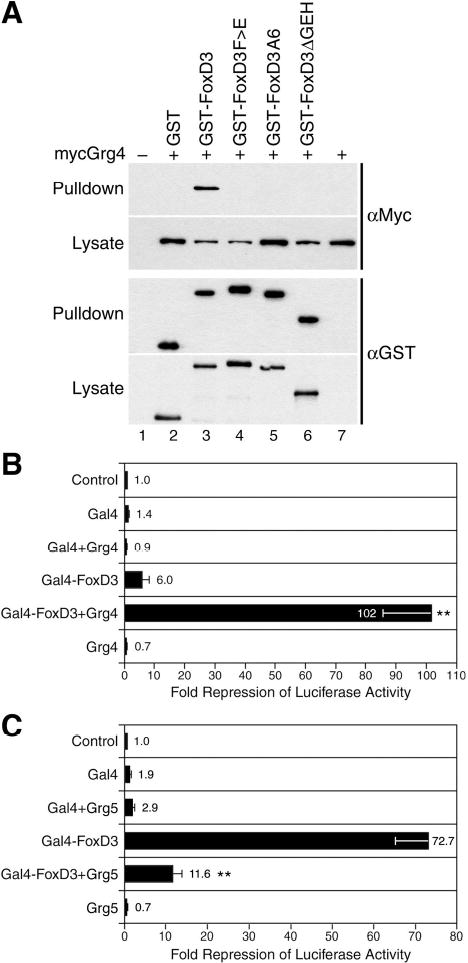

To determine whether FoxD3 can physically associate with Groucho corepressors, protein interaction in the Xenopus embryo was assessed using a GST pulldown assay. We examined the interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4 (Groucho-related gene 4), a Groucho family member that is ubiquitously expressed throughout early Xenopus development (42). The C-terminal region of FoxD3 (residues 194-371) was fused to Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST), and GST-FoxD3 was coexpressed with epitope-tagged Grg4 (myc-Grg4) in Xenopus embryos. At the gastrula stage, the interaction of myc-Grg4 with GST or GST-FoxD3 was determined using glutathione-coupled sepharose beads to pull down protein complexes. Western blot analysis of the recovered complexes indicated that while Grg4 did not bind GST alone, GST-FoxD3 and Grg4 interacted strongly (Fig. 5A, lanes 2–3). To determine whether the physical interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4 was dependent on the eh1/GEH motif, the GEH mutations and deletion described above were incorporated into GST-FoxD3. In each case, mutation (GST-FoxD3F>E and GST-FoxD3A6) or deletion (GST-FoxD3ΔGEH) of the eh1/GEH motif resulted in a complete loss of interaction between FoxD3 and Grg4 (Fig. 5A, lanes 4–6). Equal expression of the GST fusion proteins and myc-Grg4 was confirmed by western blot analysis of embryo lysates, and equal recovery of GST fusion proteins in pulldown samples was also confirmed (Fig. 5A). Taken together, the results indicate that FoxD3 recruits Groucho corepressors via direct binding to the eh1/GEH motif, and that this interaction is essential for transcriptional repression and mesoderm induction.

FIGURE 5. FoxD3 physically and functionally interacts with Grg4 via an eh1/GEH motif.

A, At the one-cell stage embryos were injected with mRNA encoding myc-Grg4 alone (2 ng), or in combination with the indicated GST-FoxD3 (194-371) fusion constructs or GST (300 pg). Protein complexes were recovered from gastrula lysates with glutathionesepharose beads (Pulldown), and were analyzed by western blotting with anti-Myc (top panels) and anti-GST (bottom panels) antibodies. Equal expression of proteins in each sample was confirmed by western blot analysis of lysates (Lysate). Recovery of Grg4 in pulldown complexes was observed for GST-FoxD3 (lane 3), but not for the GEH point or deletion mutants (lanes 4-6) or for GST alone (lane 2). As negative controls, uninjected embryos (lane 1) and embryos injected with myc-Grg4 alone were also analyzed (lane 7). B, To assess the functional interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4 in transcriptional repression, embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with a low dose of Gal4-FoxD3 (10 pg) alone or in combination with Grg4 (1 ng), and at the two-cell stage a mixture of 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase (100 pg) and CMV-Renilla Luciferase (10 pg) DNAs was injected. As negative controls, embryos injected with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4) alone or together with Grg4, or with Grg4 alone were analyzed. Animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were assayed for luciferase activity at the midgastrula stage. C, To assess the dependence of FoxD3 transcriptional activity on Groucho activity, embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with a strongly repressing dose of Gal4-FoxD3 (100 pg) alone or in combination with Grg5 (500 pg), and at the two-cell stage a mixture of 5xUAS-Gsc-Luciferase (100 pg) and CMV-Renilla Luciferase (10 pg) DNAs was injected. As negative controls, embryos injected with the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (Gal4) alone or together with Grg5, or with Grg5 alone were analyzed. Animal explants prepared at the blastula stage were assayed for luciferase activity at the midgastrula stage. Values shown in B and C are normalized to Renilla luciferase activity, and represent fold repression of basal reporter activity in the absence of injected mRNAs (Control). For each panel the mean and standard error for at least four independent experiments is presented. Statistical significance was assessed using the student’s t-TEST (**, p<0.01).

The functional interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4 in transcriptional repression was examined using the Gal4-UAS reporter system. The ability of FoxD3 to directly bind Grg4 suggests that increasing Grg4 levels in the embryo may potentiate the transcriptional repression activity of FoxD3. While the Gal4-FoxD3 fusion protein containing the C-terminal region (residues 194–371) could maximally repress transcription of the 5xUAS-Gsc-luciferase reporter nearly 250-fold (Fig. 3B), dosage studies indicated that the degree of repression was directly related to the amount of Gal4-FoxD3 RNA injected (data not shown). At low doses of Gal4-FoxD3 (10 pg), luciferase activity was reproducibly repressed ~6-fold in animal pole explants (Fig. 5B). Using this suboptimal dose of Gal4-FoxD3, the ability of Grg4 to enhance the transcriptional repression activity of FoxD3 was examined. While Grg4 alone or in combination with Gal4 had no effect on basal level transcription, coexpression of Grg4 with low dose Gal4-FoxD3 resulted in a synergistic enhancement of transcriptional repression activity (102-fold reduction of luciferase activity) (Fig. 5B). To determine if FoxD3 repression activity was dependent on Groucho function, Gal4-FoxD3 was coexpressed with Grg5, a natural dominant inhibitor of Groucho corepressor activity (43). At the dose injected (100 pg), Gal4-FoxD3 repressed basal level transcription ~73-fold, and coexpression of Grg5 reduced repression to ~12-fold, indicating that endogenous Groucho function is required for the transcriptional repression activity of Gal4-FoxD3 (Fig. 5C). Grg5 alone or in combination with Gal4 had little effect. These results demonstrate a functional interaction of FoxD3 with Groucho proteins in transcriptional repression, and provide strong support for the conclusion that FoxD3 recruits Groucho corepressors to repress transcription and induce mesoderm in Xenopus.

DISCUSSION

We have used biochemical, transcriptional and developmental analyses to define the functional domains and a transcriptional cofactor required for FoxD3 function in Xenopus. A strong transcriptional repression domain was identified in the C-terminus of Xenopus FoxD3 that is required for biological activity. A consensus eh1/GEH Groucho corepressor interaction motif is present within the repression domain and this motif is conserved in all FoxD3 orthologs. The eh1/GEH motif is essential for the mesoderm induction and transcriptional repression activities of FoxD3, as well as for the direct physical interaction of FoxD3 and Grg4. In transcriptional assays, Grg4 synergistically enhances and Grg5 inhibits the repression activity of FoxD3, providing further support for a functional interaction of FoxD3 with Groucho corepressors. Taken together, the results demonstrate that FoxD3 interacts with Groucho corepressors via a conserved eh1/GEH motif, and that this interaction is required for the repression of transcription and induction of mesodermal cell types in the Xenopus embryo. Furthermore, the mechanistic studies we report here suggest that in the Xenopus gastrula, FoxD3 recruits Groucho corepressors to target gene promoters and the resulting transcriptional repression of FoxD3 target genes promotes the induction of mesoderm.

Cells of the Xenopus blastula are competent to respond to FoxD3, and in these developmentally responsive embryonic cells we have shown that FoxD3 functions as a Groucho-dependent transcriptional repressor. Previous studies of FoxD3 in cell culture and in neural crest support this conclusion. In 293 and HeLa cells, mouse FoxD3 repressed transcription of a co-transfected reporter plasmid (9). Similarly, chick FoxD3 strongly represses the transcription of a reporter in co-transfected chicken embryo fibroblasts, and the repression domain maps to a C-terminal region that contains the conserved eh1/GEH motif we identified in all FoxD3 orthologs (31). In studies of Xenopus mesoderm induction and neural crest development, an Engrailed-FoxD3 fusion protein containing the transcriptional repression domain of Drosophila Engrailed and the WH DNA-binding domain of FoxD3 was functionally identical to native FoxD3 (17,18,30). The Engrailed repression domain contains an eh1/GEH motif that mediates recruitment of Groucho corepressors (38,41,56). This suggests that a heterologous eh1/GEH motif can recruit Groucho corepressors to FoxD3 target genes via the FoxD3 WH domain, and that this is sufficient to mimic the biological function of native FoxD3. Taken together, these studies argue strongly that FoxD3 regulates the development of mesoderm and neural crest by recruitment of Groucho corepressors to repress target gene transcription.

In contrast to our results, it has been reported that FoxD3 functions as a transcriptional activator in a context-dependent or lineage-specific manner. In co-transfected 293 cells, mouse FoxD3 was found to activate transcription of reporters containing regulatory elements of Osteopontin, FoxA1, or FoxA2 (57). Interestingly, FoxD3 activates FoxA1 and FoxA2 in a narrow dose range, and transcriptional activation was not observed at higher doses of FoxD3. The complexity of the response of FoxA1 and FoxA2 to FoxD3 is further demonstrated by the ability of Oct4, a known transcriptional activator, to inhibit the transcriptional response of FoxA1 and FoxA2 to FoxD3. Given that mouse FoxD3 can also function as a repressor in 293 cells, as discussed above, these observations suggest that the transcriptional activity of FoxD3 may be dependent on promoter context and/or the availability of transcriptional cofactors that result in activation of certain targets and repression of others. It should also be noted that the mammalian FoxD3 proteins contain several polyalanine and polyglycine sequences that are not present in other FoxD3 orthologs, and these sequences may confer additional transcriptional functions on the mammalian proteins.

An activation function for FoxD3 has also been suggested in zebrafish somitogenesis (58). In a yeast one-hybrid screen for regulators of the myogenic factor myf5, zebrafish FoxD3 was identified as a protein that binds to a somite-specific regulatory element of myf5. In cell culture studies, FoxD3 weakly activated (2–4-fold) a transcriptional reporter containing the myf5 regulatory element. Consistent with a role in myf5 regulation, FoxD3 is coexpressed with myf5 in somites and in presomitic mesoderm of the zebrafish. FoxD3 knockdown resulted in a loss of myf5 expression in somites during the 8–16-somite stage, but had no effect on myf5 expression in the presomitic mesoderm. At these stages, FoxD3 is also expressed in the zebrafish tailbud, but myf5 is not. Interestingly, ectopic myf5 expression was observed in the tailbud domain of FoxD3 knockdown embryos. These results indicate that the regulatory relation of FoxD3 and myf5 differs in distinct regions of the somite-stage zebrafish embryo. In newly formed somites FoxD3 activates myf5 expression, in the presomitic mesoderm FoxD3 has no apparent influence on myf5 expression, and in the tailbud FoxD3 inhibits myf5 expression. Therefore, the transcriptional function of FoxD3 may differ in distinct lineages of the somite-stage zebrafish, perhaps due to the lineage-specific expression of FoxD3 coactivators, corepressors, or other interacting factors.

In our study of FoxD3, we find no evidence of transcriptional activation function in the Xenopus gastrula. No domains of FoxD3 were identified that were capable of activating reporter transcription, and the biological activity of FoxD3 was completely dependent on the eh1/GEH Groucho interaction motif. Furthermore, a VP16-FoxD3 fusion protein containing the strong activation domain of HSV VP16 and the WH DNA-binding domain of FoxD3 not only failed to mimic the activity of native FoxD3, but dominantly inhibited the activity of FoxD3 in both mesoderm induction and neural crest specification (17,18,30). It is important to emphasize that our experiments were performed in the Xenopus gastrula, providing a cellular and embryonic context that is equivalent to that of endogenous FoxD3. So although FoxD3 may have distinct transcriptional functions in other lineages or at other stages of development, we can strongly conclude that FoxD3 functions as a Groucho-dependent transcriptional repressor to regulate Xenopus mesodermal development.

FoxD3 is an essential transcriptional regulatory protein for multiple developmental processes in vertebrates. Studies of neural crest development in Xenopus, zebrafish and chick indicate that FoxD3 regulates the determination, survival, migration, and/or differentiation of neural crest lineages (13–20), while in the mouse embryo, FoxD3 is essential for maintenance of embryonic and trophoblast stem cells (21,23). Embryonic stem cells, trophoblast stem cells and neural crest progenitors are multipotent cell types, and the requirement for FoxD3 in each of these cell types suggests a conserved role for FoxD3 in maintaining cellular multipotency. The functional interaction of FoxD3 and Groucho corepressors we describe in Xenopus mesoderm induction may provide mechanistic insight into FoxD3 function in neural crest and stem cells. Mouse Grg3 and Grg4 and Xenopus Grg4 are coexpressed with FoxD3 in neural crest lineages (42,59–61), consistent with a potential functional interaction of FoxD3 and Groucho corepressors in neural crest cells, although a direct role for Groucho corepressors in neural crest development has yet to be demonstrated. In addition, microarray analysis has shown that mouse Grg3 and Grg4 are enriched in embryonic stem cells when compared to differentiated cell types (62). The coexpression of FoxD3 and Groucho corepressors in these progenitor cells suggests that FoxD3 repression of target gene transcription may be essential for maintaining multipotency in diverse progenitor cell populations. This is a compelling idea given the evidence that transcriptional repression of differentiation genes is a key mechanism of stem cell and progenitor cell maintenance (63–65). Further work will be necessary to determine if FoxD3 has similar transcriptional activity and common target genes in neural crest and stem cells, and whether FoxD3 function in these progenitor populations is dependent on an interaction with Groucho corepressors.

The interaction of FoxD3 and Groucho we describe appears to reflect a conserved functional characteristic of the entire FoxD subclass. Xenopus FoxD1 and FoxD5, and chick FoxD2 each function as developmentally important transcriptional repressors and contain a C-terminal repression domain (31,66,67). In fact, every vertebrate and invertebrate member of the FoxD subclass (27 proteins) contains a C-terminal sequence with high similarity to the eh1/GEH Groucho interaction motif, including ancestral FoxD proteins in marine sponge, Ciona, and Amphioxus (68–71). While the identification of Groucho orthologs in primitive species (72) suggests that the eh1/GEH-like sequences may be functional, it remains to be determined for many of the FoxD subclass proteins whether the eh1/GEH sequences mediate Groucho interaction and transcriptional repression. Taken together, however, these data suggest an ancient origin for the eh1/GEH motif-dependent recruitment of Groucho corepressors by FoxD subclass proteins.

FoxD3 is an essential transcriptional regulator of multiple developmental processes, and our results demonstrate that in Xenopus mesoderm induction FoxD3 functions as a Groucho-dependent transcriptional repressor. Among a number of questions for future work, it will be important to determine the transcriptional activity and identify the transcriptional targets of FoxD3 in distinct lineages. Whether FoxD3 is a context-dependent regulator that can activate or repress transcription in a cell type-specific or target-specific manner will require further functional analyses in a number of FoxD3-expressing lineages. Furthermore, identification of FoxD3 target genes in the organizer, neural crest and stem cells will reveal if a common regulatory pathway is utilized in each of these cell types, or if there are lineage-specific mechanisms of FoxD3 function. Ongoing studies of FoxD3 in multiple embryonic settings are likely to provide further insight into the developmental and molecular mechanisms of vertebrate embryogenesis.

Footnotes

We thank Doug Epstein, Trish Labosky and Jean-Pierre Saint-Jeannet for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Hans Clevers, Peter Klein, and Malcolm Whitman for providing plasmids, and Christine Reid for assistance with statistical analyses. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (GM64768) and the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences to D.S.K.

References

- 1.Carlsson P, Mahlapuu M. Dev Biol. 2002;250:1–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lehmann OJ, Sowden JC, Carlsson P, Jordan T, Bhattacharya SS. Trends Genet. 2003;19:339–344. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohl BS, Knochel W. Gene. 2005;344:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dirksen ML, Jamrich M. Dev Genet. 1995;17:107–116. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020170203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freyaldenhoven BS, Freyaldenhoven MP, Iacovoni JS, Vogt PK. Cancer Res. 1997;57:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelsh RN, Dutton K, Medlin J, Eisen JS. Mech Dev. 2000;93:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Labosky PA, Kaestner KH. Mech Dev. 1998;76:185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odenthal J, Nusslein-Volhard C. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:245–258. doi: 10.1007/s004270050179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutton J, Costa R, Klug M, Field L, Xu D, Largaespada DA, Fletcher CF, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Klemsz M, Hromas R. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23126–23133. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamagata M, Noda M. Neurosci Lett. 1998;249:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lef J, Dege P, Scheucher M, Forsbach-Birk V, Clement JH, Knochel W. Int J Dev Biol. 1996;40:245–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheucher M, Dege P, Lef J, Hille S, Knochel W. Roux's Arch Dev Biol. 1995;204:203–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00241274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheung M, Chaboissier MC, Mynett A, Hirst E, Schedl A, Briscoe J. Dev Cell. 2005;8:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dottori M, Gross MK, Labosky P, Goulding M. Development. 2001;128:4127–4138. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.21.4127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kos R, Reedy MV, Johnson RL, Erickson CA. Development. 2001;128:1467–1479. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lister JA, Cooper C, Nguyen K, Modrell M, Grant K, Raible DW. Dev Biol. 2006;290:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl BS, Knochel W. Mech Dev. 2001;103:93–106. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00334-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasai N, Mizuseki K, Sasai Y. Development. 2001;128:2525–2536. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.13.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart RA, Arduini BL, Berghmans S, George RE, Kanki JP, Henion PD, Look AT. Dev Biol. 2006;292:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitlock KE, Smith KM, Kim H, Harden MV. Development. 2005;132(24):5491–5502. doi: 10.1242/dev.02158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanna LA, Foreman RK, Tarasenko IA, Kessler DS, Labosky PA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2650–2661. doi: 10.1101/gad.1020502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pera MF, Reubinoff B, Trounson A. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:5–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tompers DM, Foreman RK, Wang Q, Kumanova M, Labosky PA. Dev Biol. 2005;285:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaklichkin S, Steiner AB, Kessler DS. Transcriptional repression in Spemann’s Organizer and the formation of dorsal mesoderm. In: Grunz H, editor. The Vertebrate Organizer. Springer-Verlag Press; Heidelberg: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Robertis EM, Larrain J, Oelgeschlager M, Wessely O. Nat Rev Genet. 2000;1:171–181. doi: 10.1038/35042039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harland R, Gerhart J. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:611–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heasman J. Development. 2006;133:1205–1217. doi: 10.1242/dev.02304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whitman M. Dev Cell. 2001;1:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schier AF. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:589–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.041603.094522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner AB, Engleka MJ, Lu Q, Piwarzyk EC, Yaklichkin S, Lefebvre JL, Walters JW, Pineda-Salgado L, Labosky PA, Kessler DS. Development. 2006;133:4827–4838. doi: 10.1242/dev.02663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freyaldenhoven BS, Freyaldenhoven MP, Iacovoni JS, Vogt PK. Oncogene. 1997;15:483–488. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher AL, Caudy M. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1931–1940. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Courey AJ, Jia S. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2786–2796. doi: 10.1101/gad.939601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen G, Courey AJ. Gene. 2000;249:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jennings BH, Pickles LM, Wainwright SM, Roe SM, Pearl LH, Ish-Horowicz D. Mol Cell. 2006;22:645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen G, Fernandez J, Mische S, Courey AJ. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2218–2230. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paroush Z, Finley RL, Jr, Kidd T, Wainwright SM, Ingham PW, Brent R, Ish-Horowicz D. Cell. 1994;79:805–815. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimenez G, Paroush Z, Ish-Horowicz D. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3072–3082. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Celis JF, Ruiz-Gomez M. Development. 1995;121:3467–3476. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubnicoff T, Valentine SA, Chen G, Shi T, Lengyel JA, Paroush Z, Courey AJ. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2952–2957. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.22.2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolkunova EN, Fujioka M, Kobayashi M, Deka D, Jaynes JB. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2804–2814. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Molenaar M, Brian E, Roose J, Clevers H, Destree O. Mech Dev. 2000;91:311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roose J, Molenaar M, Peterson J, Hurenkamp J, Brantjes H, Moerer P, van de Wetering M, Destree O, Clevers H. Nature. 1998;395:608–612. doi: 10.1038/26989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Umbhauer M, Boucaut JC, Shi DL. Mech Dev. 2001;109:61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00517-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brugmann SA, Pandur PD, Kenyon KL, Pignoni F, Moody SA. Development. 2004;131:5871–5881. doi: 10.1242/dev.01516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yao J, Kessler DS. Mesoderm induction in Xenopus: oocyte expression system and animal cap assay. In: Tuan RS, Lo CW, editors. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 137: Developmental Biology Protocols, Vol. III. Humana Press; Totowa: 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nieuwkoop PD, Faber J. Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin) Second edition Ed. North Holland Publishing Company; Amsterdam: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson PA, Melton DA. Curr Biol. 1994;4:676–686. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rupp RA, Snider L, Weintraub H. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1311–1323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.11.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agius E, Oelgeschlager M, Wessely O, Kemp C, De Robertis EM. Development. 2000;127:1173–1183. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.6.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matunis MJ, Michael WM, Dreyfuss G. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:164–171. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.1.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaestner KH, Knochel W, Martinez DE. Genes Dev. 2000;14:142–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan H, Liao X. Biophys J. 2003;85:3248–3254. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74742-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin C, Marsden I, Chen X, Liao X. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:683–690. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe M, Whitman M. Development. 1999;126:5621–5634. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.24.5621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith ST, Jaynes JB. Development. 1996;122:3141–3150. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo Y, Costa R, Ramsey H, Starnes T, Vance G, Robertson K, Kelley M, Reinbold R, Scholer H, Hromas R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:3663–3667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062041099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HC, Huang HY, Lin CY, Chen YH, Tsai HJ. Dev Biol. 2006;290:359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koop KE, MacDonald LM, Lobe CG. Mech Dev. 1996;59:73–87. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leon C, Lobe CG. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:11–24. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199701)208:1<11::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dehni G, Liu Y, Husain J, Stifani S. Mech Dev. 1995;53:369–381. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramalho-Santos M, Yoon S, Matsuzaki Y, Mulligan RC, Melton DA. Science. 2002;298:597–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1072530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boiani M, Scholer HR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:872–884. doi: 10.1038/nrm1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, Gifford DK, Melton DA, Jaenisch R, Young RA. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boyer LA, Plath K, Zeitlinger J, Brambrink T, Medeiros LA, Lee TI, Levine SS, Wernig M, Tajonar A, Ray MK, Bell GW, Otte AP, Vidal M, Gifford DK, Young RA, Jaenisch R. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mariani FV, Harland RM. Development. 1998;125:5019–5031. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sullivan SA, Akers L, Moody SA. Dev Biol. 2001;232:439–457. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Adell T, Muller WE. Gene. 2004;334:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Imai KS, Satoh N, Satou Y. Development. 2002;129:3441–3453. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yaklichkin S, Vekker A, Stayrook S, Lewis M, Kessler DS. 2006 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-201. submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu JK, Holland ND, Holland LZ. Dev Dyn. 2002;225:289–297. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Satou Y, Imai KS, Levine M, Kohara Y, Rokhsar D, Satoh N. Dev Genes Evol. 2003;213:213–221. doi: 10.1007/s00427-003-0319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]