Abstract

The broad goal of the Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) study was to address, and understand, a range of issues related to the recruitment and retention of Blacks and other minorities in biomedical research studies. The specific aim of this analysis was to compare the self-reported willingness of Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites to participate as research subjects in biomedical studies, as measured by the Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale and the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale. The Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire, a 60 item instrument, was administered to 1,133 adult Blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Whites in 4 U.S. cities. The findings revealed no difference in self-reported willingness to participate in biomedical research, as measured by the LOP Scale, between Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites, despite Blacks being 1.8 times as likely as Whites to have a higher fear of participation in biomedical research on the GPFF Scale.

Keywords: Minority recruitment, clinical studies, participation in research, Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Syphilis Study at Tuskegee (1932–72), a study of 399 syphilitic African American male sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama, who were followed for 40 years so that researchers could observe the effects of untreated syphilis on various organ systems, is arguably the most infamous biomedical research study in U.S. history,1–5 Today, there is wide-spread belief that a major legacy of that unethical research study is a strong reluctance among many African Americans to participate in clinical research studies as a result of the abuses for fear of further abuses.6–7 While a considerable amount has been written about the long-lasting effects of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee on the Black community, most of this work has been from a legal, historical, ethical, or access to health care perspective.8–20 The term Legacy of the Tuskegee Study, which originally was used only to describe the events directly resulting from that infamous study, has come to be used as metaphor for the abuse of Blacks within biomedical research.21,22

Surprisingly, prior to 1997, little research had directly examined whether any differential participation of Blacks or other minorities in biomedical studies from that of Whites was due to the effects of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee or to other factors. A literature review on this topic, published as a companion article in this same volume of this journal [see McCallum et al.], found eight articles that had either quantitative or qualitative data assessing both awareness (general or specific) of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee and self-reported willingness to participate in biomedical research.23–30 Of the four quantitative articles,27–30 one of them inquired about willingness to participate in research dealing only with AIDS and only with Black subjects.27 The three remaining quantitative studies compared responses of Blacks with those of Whites. One of these three focused solely on participation in cancer clinical trials28 while the remaining two quantitative studies addressed participation in biomedical research, in general.29,30 Thus, the published literature on addressing the comparative self-reported willingness of Blacks and Whites to participate in biomedical research, in the context of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, is small in the number of studies published (three) as well as limited in detailed probing about willingness to participate. For example, two of these studies appear to have asked just a single question on willingness to participate.

The title of the larger project of which the present one is a part, The Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP), is intended to recognize both the historical event of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee as well as to acknowledge that the term Tuskegee legacy has become a metaphor for the abuse of research subjects in biomedical studies. The Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) had its origins in a 1994 bioethics conference held at the University of Virginia entitled The Tuskegee Legacy: Doing Bad in the Name of Good; the origins and development of the Tuskegee Legacy Project have been fully described elsewhere.31

The broad goal of the overall TLP study was to address, and understand, a range of issues related to the recruitment and retention of Blacks and other minorities in biomedical research studies. Attainment of this goal is critical in order to ensure that the findings from biomedical studies provide health data on the diverse populations of the U.S., to help biomedical researchers achieve compliance with 1994 NIH Guidelines for the Inclusion of Women and Minorities in clinical studies,32 and to provide empirical suggestions for intervention studies on enlisting minorities into biomedical studies, including clinical trials, all to support the goal of reducing health disparities at the national level.

The specific aim of this report is to compare the self-reported willingness of Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites to participate as research subjects in biomedical studies, as measured by the Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale and the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale. The primary contrast of interest in this first study using the TLP Questionnaire is between Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites, with a secondary interest in clarifying if these associations generalize to Hispanics.

Methods

Overview

The Tuskegee Legacy Project was designed to administer the TLP Questionnaire, a 60 item instrument, via random-digit dial telephone interviews to 300 Blacks, 400 Whites and 200 Hispanics aged 18 years and older in 4 city/county areas: Birmingham/Jefferson County, Alabama; Tuskegee/Macon County, Alabama; Hartford/Hartford County, Connecticut; and San Antonio/Bexar County, Texas. The TLP Questionnaire interviews were conducted in the 4 city/county areas between March 1999 and November 2000. This TLP Study was approved by the University of Connecticut Health Center Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Development of the survey instrument: The Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) Questionnaire

The primary research instrument was the Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) Questionnaire, which was a questionnaire developed between 1994–97 by a multi-disciplinary, multi-university research team within the Northeastern Minority Oral Health Research Center (NMOHRC), an NIDR/NIH Regional Research Center for Minority Oral Health, which was funded from 1991–2000. The TLP Questionnaire addresses a range of issues related to the recruitment of minorities into biomedical studies. Specifically, the TLP Questionnaire focuses on whether minorities (compared with Whites) are more reluctant to participate in biomedical research studies and, if so, why. The TLP Questionnaire was developed via a series of pilot studies conducted over a three-year period, beginning with focus group research pilots to identify topics and best language, which led to questionnaire development pilot studies, followed by small pilot studies (with 40–60 subjects each) that field tested the TLP Questionnaire, followed by a final review by the National Tuskegee Legacy Committee at its workshop meeting at Tuskegee University in January 1996, and finally a major pilot study testing a Random-digit Dial (RDD) administration of the TLP Questionnaire to 200 subjects in Huntsville, Alabama in 1998.

The TLP Questionnaire had 60 questions (8 of which sought demographic information) with 2 identified conceptual domains of interest (the Guinea Pig Fear Factor Domain and the Likelihood of Participation Domain) which were validated as scales using standardized psychometric analysis techniques based upon the data from these 4 cities; in this report, these 2 scales are referred to as the GPFF Scale and the LOP Scale. The standardized psychometric analysis techniques used to validate the GPFF Scale and the LOP Scale consisted of multitrait scaling analysis which is built upon the logic of the multitrait-multitmethod approach described by Campbell and Fiske.33–35 Specifically, 3 methods were used to test whether the GPFF domain and LOP domain met the psychometric standards for scales using 3 standard tests; 1) item internal consistency (using an item-total correlation cut-off of 0.40 or more between the item and the total scores of the scale), 2) item discriminant validity (using a 95% Confidence Interval cut-off point to establish that the correlation between the item and its hypothesized scale was significantly higher than between the item and its correlation with all other scales), and 3) internal consistency reliability (using a cut-off of Cronbach’s alpha at 0.70 to establish that the items within a scale shared common variance).

A pre-data analysis a priori decision was made regarding how to treat the Not Quite Sure (NQS) category responses when dichotomizing the five point Likert scaled responses for willingness to participate questions into two response categories, i.e., converting the original Very Likely, Somewhat Likely, NQS, Somewhat Unlikely, Very Unlikely responses into Likely vs. Unlikely categories. As the focus of analysis was on comparing willingness to participate, the decision was made not to include the NQS responses in the positive response category of Likely. Thus for the willingness to participate questions, the NQS response was put into the Unlikely category, when dichotomous categories were created. This was largely based upon two considerations: 1) the preference to be conservative in the estimation of willingness to participate in any racial/ethnic group (i.e., care taken not to overstate the percent Likely), and 2) the line of reasoning that if respondents did not indicate Very Likely or Somewhat Likely during the interview obtaining self-reported anticipated behaviors, then the likelihood of them acting more altruistically under the pressure of the real moment would be low.

Rationale for the selection of the cities

The cities of Hartford, Connecticut and Birmingham, Alabama were selected in order to provide two cities of comparable size with demographic similarities that would provide regional variation as regards respondents’ attitudes and opinions. An additional selection criterion was that both cities had major medical centers and therefore had populations likely to be invited to participate in medical studies. The city of San Antonio was selected as it was identified as the U.S. city with a major medical center that would provide the most efficient RDD yield for Mexican Americans, thus providing balance to Hartford’s Puerto Rican population. The decision to include the city of Tuskegee in the study was based upon its historical relevance and the interest in administering the TLP Questionnaire to residents of the historical epicenter of the issue at hand.

The Random-Digit Dial survey process

The Random-Digit Dial (RDD) interviews for the 4-city TLP Study was administered by the Survey Research Unit of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (SRU at UAB). The SRU at UAB used an RDD process to plan the completion of 25-minute telephone interviews with 900 adults in the following groups: 1) 300 Blacks (100 each in Hartford, Birmingham, and Tuskegee); 2) 200 Hispanics (100 Puerto Rican Hispanics in Hartford and 100 Mexican Americans in San Antonio); and, 3) 400 non-Hispanic Whites (100 each in Hartford, Birmingham, Tuskegee, and San Antonio).

The target population for the RDD survey for the Tuskegee Legacy Projects consisted of non-institutionalized people aged 18 years or older living in households with working telephones in the 4 targeted cities. The primary sampling unit for the calling area was the Central Office Code (COC), the three-digit telephone exchange used for local calling areas. This provided a circumscribed area for geographic exposure and increased the likelihood of contacting households through RDD.

The RDD sample of households in each of the 4 cities/counties was supplied by Survey Sampling, Inc. and was partially screened for non-working or business numbers. A total of 13 interviewers were trained for the survey using full CATI technology. The protocol required waiting one hour between calling attempts; a given number could be called up to 3 times per shift. If a respondent indicated a reluctance to participate when initially contacted, a second, and final, call was made to extend the invitation to participate. If a respondent refused to participate in the interview on this second invitation, that number was coded as a final refusal and not contacted again. Unresolved numbers were retired after 20 attempts. Interviewers were supervised at all times and randomly electronically monitored a minimum of four times per month.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were designed to determine if the 3 racial/ethnic groups (Blacks, Whites and Hispanics) differed on the GPFF Scale and the LOP Scale, adjusting for age, sex, education, income, and city. ANCOVA multivariate analysis was used to determine whether the GPFF Scale or the LOP Scale scores differed across the racial/ethnic groups, adjusting for key variables; if any statistically significant differences were observed in the ANCOVA analysis, a logistic regression analysis was to be performed on that variable to generate odds ratios. The final ANCOVA multivariate analyses resulted from a two-step process. Step 1 consisted of a bivariate analysis of each independent variable (race/ethnicity, age, sex, education, income, and city) by each dependent variable with alpha set at 0.05. Step 2 consisted of an ANCOVA multivariate analysis for the study sample as a whole with race/ethnicity as the independent variable with the model for either of the dependent variables (GPFF and LOP) including only those covariates that achieved statistical significance in Step 1. Finally, for each dependent variable (GPFF and LOP) for which statistically significant findings were observed, pairwise comparisons, using the post hoc Bonferroni criterion, were conducted to explore two-way differences, i.e., Blacks vs. Whites, Blacks vs. Hispanics, and Hispanics vs. Whites.

Results

The TLP Questionnaire was administered by the SRU at UAB via RDD telephone interviews to 1,133 adult Blacks, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites in 4 city/county areas: Birmingham/Jefferson County, Alabama; and Tuskegee/Macon County, Alabama; Hartford/Hartford County, Connecticut: and San Antonio/Bexar County, Texas with response rates of 70%, 65%, 49% and 50%, respectively.

The final study sample (n=l,133) consisted of 353 Blacks (31.1%), 157 Hispanics (13.9%), and 623 non-Hispanic Whites (55.0%). The Hispanic group consisted of 73.9% Mexican Americans (n=116) and 26.1% Puerto Rican Americans (n=4l). The Puerto Rican group was the only one that did not reach its targeted enrollment goal of 100; the high number of Whites in the final study (vs. the 400 minimally desired) is simply a result of a blind RDD survey into populations with a majority of Whites. The mean age of respondents was 50.6 years (s.d. 17.2 years) with a range from age 19 to 94 years; 51.7% of the respondent sample was female. The income distribution showed 31.1% earning less than $20,000 per year, 55.5% earning between $20,000 and $74,999, and 13.3% earning more than $74,999. The distribution of subjects by educational level revealed 16.8% with less than a high school degree, 55% with a high school degree and/or some college, and 28% with a college degree or higher education level. Table 1 shows the age, sex, education, and income distribution of the 1,133 subjects stratified by race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

DISTRIBUTION OF THE 1133 SUBJECTS IN THE TLP STUDY BY AGE, SEX, EDUCATION, INCOME WITHIN ETHNIC GROUP

| Characteristic | Blacka,b(n=353) | Whitea,c(n=623) | Hispanicb,c(n=157) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (± s.d.) | 49.1 ± 16.5 | 53.8 ± 17.0 | 41.5 ± 16.1 |

| Percent male | 52.1 | 48.3 | 39.5 |

| Education level, % | |||

| <H.S. graduate | 21.6 | 11.8 | 14.0 |

| H.S. graduate | 60.5 | 51.3 | 61.0 |

| College graduate | 17.9 | 36.9 | 25.0 |

| Income level, % | |||

| <$20,000 | 42.8 | 21.3 | 41.7 |

| $20–74,999 | 52.1 | 58.4 | 52.5 |

| ≥ $75,000 | 5.1 | 20.3 | 5.8 |

Note: Statistically significant contrasts:

For Blacks vs. Whites contrast: differed on age, education and income (p≤.05)

For Blacks vs. Hispanics contrast: differed on age and sex (p≤.05)

For Hispanics vs. Whites contrast: differed on age, sex, education and income (p≤.05)

While some regional demographic differences were noted, this first paper focuses on the study population as a whole. To acknowledge, and account for, recognized cultural differences between the four cities (i.e., above and beyond simple demographic differences), the variable of city was included as a separate covariate in all multivariate analyses of this analysis of the study sample as a whole.

Box 1 consists of the key questions from the TLP Questionnaire that formed the basis for this analysis. It shows both the precise wording of the four key questions and their subparts (Q16, Q17a–g, Q18a–i, and Q19i–v), and elements of questions used to create the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale and the Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale.

Box l. QUESTIONS FROM THE TLP QUESTIONNAIRE ON WILLINGNESS TO PARTICIPATE, AND KEY QUESTIONS THAT FORMED GPFF AND LOP SCALES

Q16. How likely are you to agree to become a participant in any kind of medical study at the present time? * [responses to Q16: VL SL NQS SUL VUL]

Q17. Would you feel the same no matter who was running the study? I’m going to read you a list of people who might run a study. For instance, how likely would you be to participate in a medical research study if it were run by:

your own doctor *

a University medical school/hospital *

the Government *

a non-profit foundation *

a tobacco company *

a drug company *

an insurance company *

[responses to Ql7a-g: VL SL NQS SUL VUL]

Q18. Each medical research study is different, so people who participate might have to do different things in different studies. How likely are you to participate in a medical study if you had to do the following:

give blood *

take IV injections *

do exercises *

be interviewed in-person *

be interviewed by telephone *

have diet limited or restricted *

take medicine by mouth *

undergo major surgery *

undergo minor surgery *

[responses to Q18a-i: VL SL NQS SUL VUL]

LOP Scale = Q16 + Q17a-g + Q18a-i

[as marked in italicized boldface above with single asterisk]

Q19. There are lots of things that might make people MOT WANT to participate in medical research studies. How much would the following interfere with your taking part in a medical research study?

any fear you have of getting AIDS **

any fear of being a ‘guinea pig’ **

any fear of results not being private or confidential **

any fear of having to pay for the research treatments **

lack of trust in research**

[responses to Q19i-v: totally a geat deal some a little not at all]

GPFF Scale = #19i-v [as marked in boldface above with double asterisks]

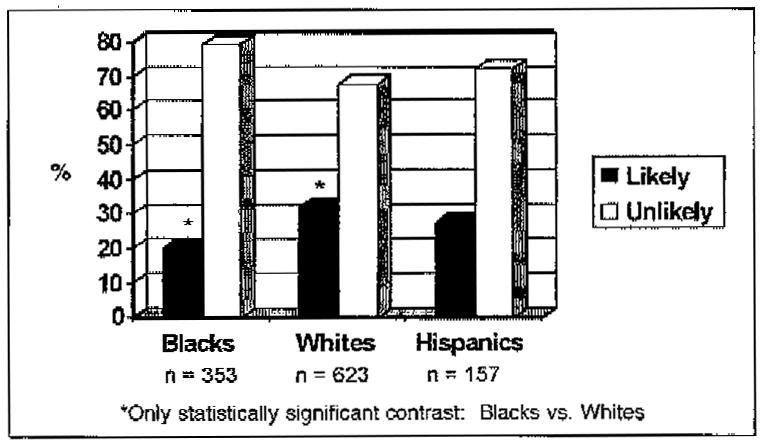

The percentage willing to participate in biomedical studies, dichotomized into Likely (Very Likely + Somewhat Likely) and Unlikely (Not Quite Sure + Somewhat Unlikely + Very Unlikely), within racial/ethnic groups is shown in Figures 1–3; these are all unadjusted bivariate analyses. The response to Q16 (considered as the overall single best gestalt question on willingness to participate) is shown in Fig 1 and reveals three clear findings: 1) only a minority of each racial/ethnic group indicated that they were likely to participate in biomedical studies (less than 31%); 2) the only statistically significant contrast in willingness to participate was found between Blacks and Whites (20.6% vs. 31.2%, respectively, p≤.05); and 3) scores for Hispanics were between Blacks and Whites, with 26.7% indicating a willingness to participate. Q17 and Q18 were intended to provide a more nuanced probe into willingness to participate, with Q17 focused on the impact of who runs the study as the key factor and Q18 focused on the impact of what one is asked to do in the study as the key factor.

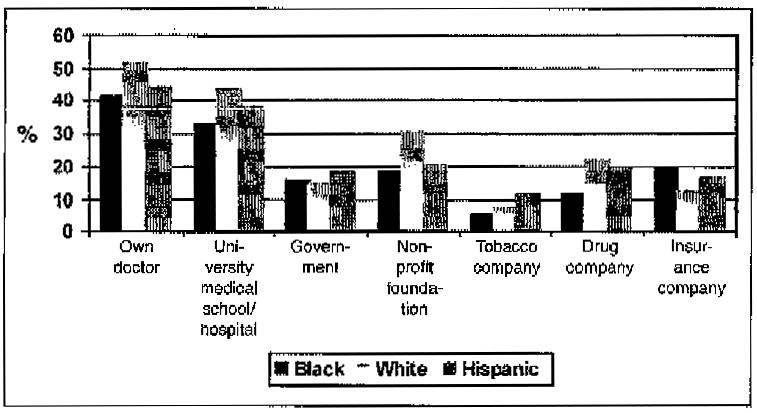

Figure 2 shows the findings from Q17 and reveals a large range in the proportion willing to participate depending upon who was conducting the study, from a high of over 50% if run by your own doctor for Whites to a low of approximately 7% for Whites if run by A tobacco company (a seven-fold difference) with comparable data for Blacks on the same two specific who runs the study factors (over 40% willing to participate if run by your own doctor and only 5% for if run by tobacco company, an eight-fold difference). In response to seven prompts in Q17 on who was conducting a study, Blacks indicated they were less likely to participate than Whites on four specific prompts and more likely to participate on only two prompts (p≤.05 for each), with Hispanics again being generally located between Blacks and the Whites. Interestingly, the three racial/ethnic groups, while showing slight (occasionally marked) differences in response to any one who probe, exhibited, on the whole, very similar ratings across the who factor, i.e., own doctor and university medical school/hospital ranked as the most trusted for all three groups while tobacco companies were clearly the lowest ranked who factor. Among the other who factors that formed the middle responses (about 15–20% willingness), government was the lowest of these middle-ranked who factors.

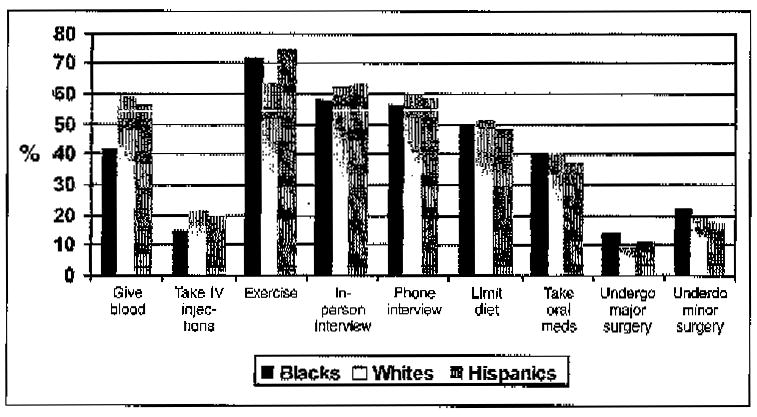

In parallel fashion, the findings from Q18 on what one is asked to do in a study are shown in Figure 3. Again, a large range is exhibited depending upon what one is asked to do in biomedical studies, and again the three racial/ethic groups demonstrate very similar ratings across the nine specific probes, i.e., they appear to more or less travel together up and down the scale of willingness to participate. For example, among Blacks the range is from over 70% being willing to exercise in studies to a low of 12–13% of Blacks being willing to take IV injections or undergo major surgery in a study, approximately a six-fold difference, with very similar findings on these same specific probes for the Whites and Hispanics. Converse to the findings in Q17 on who was running the study, in response to the nine probes in Q18 with its focus on what one is asked to do in biomedical studies, Blacks indicated they were less likely to participate than Whites on only two specific prompts, both involving blood (p≤.05 for each), more likely to participate on two prompts (p≤.05), and were equally or near equally likely to participate as Whites on five prompts (i.e., no statistically significant differences observed).

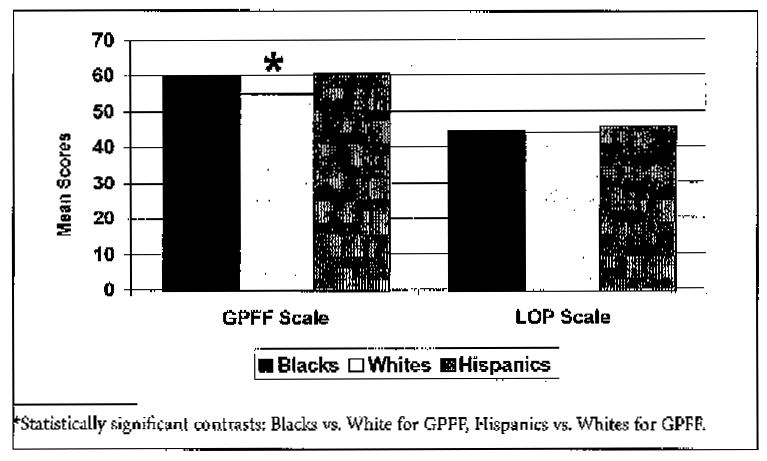

Unadjusted mean GPFF Scale and LOP Scale scores for each racial/ethnic group are shown in Figure 4, While the mean GPFF Scale score for Blacks (60.1, s.d. ± 28.3) and for Hispanics (60.1, s.d. ± 26.1) was the same, Whites had a lower mean score (54.6, s.d. ± 26.3). The two-way contrasts for mean GPFF Scale scores were statistically significantly for both the Black vs. White, and the Hispanic vs. White, contrasts (p≤.05). For the LOP Scale, there were no mean score differences across the racial/ethnic groups as Blacks had a mean LOP Scale score of 44.3 (s.d. ± 19.1), Whites a mean LOP Scale score of 43.0 (s.d. ± 21.7), and Hispanics a mean LOP Scale score of 45.6 (s.d. ± 18.7).

Table 2 shows the adjusted ANCOVA multivariate analyses for the GPFF Scale using race/ethnicity as the independent variable. The model shown in Table 2 resulted from a two-step process that adjusted for age, sex, education, income, and city. The adjusted results for the GPFF Scale show that the race/ethnicity factor was statistically significant (F=3.8, p≤.05). A post hoc test of adjusted GPFF means, using the Bonferroni criterion, revealed that Blacks had a significantly higher GPFF Scale score than Whites (p≤.05). While the GPFF of Hispanics was not statistically significantly different from either Whites or Blacks, this likely reflects the low power of this sub-analysis due to the fact that the number of Hispanics in this study was less than half (45%) the number of Blacks. Conversely, the adjusted results for the LOP Scale revealed that race/ethnicity, as the independent variable, was not statistically significant (F=0.8, p=.45).

Given that the ANCOVA adjusted analysis showed a statistically significant difference for the GPFF Scale across the racial/ethnic groups, a second step logistic regression analysis was performed on GPFF across racial/ethnic groups to generate the Odds Ratio (OR) to measure the magnitude of this observed difference. As the GPFF Scale is a continuous variable, a series of correlation analyses, seeking the maximum correlation point, between the GPFF scales score and its individual constituent items, was used to determine the best dichotomization point for the GPFF, as required for conducting the logistic regression analysis. As a result of this maximum correlation analysis, the median GPFF was used as the dichotomization cut-off point for the logistic regression analysis for the GPFF. Table 3 shows the multivariate logistic regression analysis for the GPFF Scale adjusted for race, age, sex, education, income, and city. The findings revealed that, controlling for important differences in sex, age, and city, Blacks were significantly more likely to have a GPFF Scale score above the median, indicating more fear, than in Whites (OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.4–2.4), While Hispanics were also slightly more likely than Whites to have a GPFF Scale score above the median, the OR for the Hispanic vs. White contrast was not statistically significant (OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.8–1.9).

Discussion

The TLP Study sought to determine if there is a difference between Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites concerning willingness to participate in biomedical studies, as assessed by the LOP Scale within the TLP Questionnaire. Our multivariate analyses revealed no statistically significant difference, overall, in mean. LOP Scale score for the three racial/ethnic groups. The multi-item LOP scale aimed to ensure that our measure of willingness to participate was psychometrically sound and capable of capturing some of the complexity and nuances of this particular concept.

For example, if one based the analysis of willingness to participate solely on Q16 from the TLP Questionnaire in a comparison of Blacks and Whites, a logistic regression analysis reveals that Blacks are less likely to participate as research subjects than non-Hispanic Whites (OR=0.70, p<.05) after adjusting for age, sex, education, and income. However, similarly adjusted logistic regression analyses comparing Blacks with Whites regarding the influence of who was running the study (Q17a-g) and what they would be asked to do in a study (Q18a-i), revealed that Blacks and Whites, on. the whole, were no different in their likelihood to participate based either on the who or on the what. Specifically, Blacks were somewhat more influenced than Whites by who was running the study as Blacks tended to report being somewhat less likely to participate than Whites based on the who, but not at a statistically significant level (OR=0.71, p=.07), in contrast to no differences on the what (OR=1.05, p=.78).

Thus, while we observed a null association, overall, concerning differences among the three racial/ethnic groups in their willingness to participate in biomedical research, answers to the individual components of the LOP Scale (Q16, Q17a-g, and Q18a-i) did provide useful insights into this complex concept. While Q16 (arguably the overall single best gestalt question on willingness to participate) showed a difference between Blacks and Whites in willingness to participate, this was counterbalanced by the findings from Q17a-g (who was running the study), and Q18a-I (what they would be asked to do in a study), both of which revealed that Blacks and Whites were equally likely to participate based, on both the who or the what condition. The in general differences between racial/ethnic groups (shown, by the data from Q16) disappeared when subjects were given specific study circumstances as to who was conducting the study or what subjects were asked to do within the study. Thus, it is quite clear that the concept of willingness to participate is a complex concept.

While these sub-analyses by the individual TLP Questionnaire questions 16, 17a-g and 18a-i provide detailed insights into the elements contained in the concept of willingness to participate, only the LOP Scale, taken as a whole, provides the in-depth probe most capable of providing the most valid single measure of this complex concept. Conversely, if these three individual questions (Q16, Q17a-g, and Q18a-i) had not been integrated into one variable to capture this complexity, the analysis could not have addressed the concept as a whole.

While there was no detectable difference observed in the LOP Scale across racial/ethnic groups, the data showed a statistically significant difference across the three racial/ethnic groups for the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale (p=.022, ANCOVA adjusted for age, sex, education, income, and city). A post hoc Bonferroni test for contrasts showed that this observed difference was mainly due to the higher GPFF Scale scores for Blacks than for Whites. The magnitude of this difference in GPFF Scale scores, determined by adjusted logistic regression analyses, revealed that Blacks were 1.8 times as likely as Whites to have a higher fear of participation in biomedical research. These findings indicate that fear of biomedical research, as measured by the GPFF Scale, was higher among Blacks, when adjusted for age, sex, education, income, and city.

Applying these findings from the LOP Scale and GPFF Scale to the study sample as a whole, we conclude that although Blacks are more likely to report a higher level of fear related to participation in biomedical studies, they are nevertheless just as willing as Whites to participate in biomedical research studies. While Hispanics did not differ from either Blacks or Whites on willingness to participate, Hispanics did report slightly (but not significantly) higher levels of fear related to participation in biomedical studies than Whites, Thus, based on these study findings, the recruitment of Black and Hispanic minorities for biomedical studies appears to be a fully attainable goal for most types of biomedical studies, in addition to being highly desirable for ensuring diversity within study populations in biomedical research.

It is not possible to present a full and direct comparison of the findings from this TLP Study with the findings of the three prior quantitative studies that reported on comparative self-reported willingness to participate in biomedical studies for Blacks and Whites as linked to the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Two of those studies, being tightly focused on the link with knowledge of the original USHPS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, only reported on the comparative willingness to participate for their subset of respondents who had indicated they had heard of the USPHS Syphilis Study at Tuskegee, but not for all the subjects in their study,29,30 Neither our TLP Study nor the sole remaining quantitative study28 observed statistically significant differences between Blacks and Whites on self-reported willingness to participate as subjects in biomedical studies.

However, given that all three of these quantitative studies did present other findings on distrust of biomedical research (as opposed to willingness to participate) that dearly indicated a higher level of distrust in biomedical research among their Black subjects than among their White subjects, these three quantitative studies are in general agreement with the findings from our TLP Study, which showed that Blacks were statistically significantly higher than Whites on the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale (a clear indication of increased distrust) despite not being different on the Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale.

In keeping with the above, recently published articles that have directly evaluated actual enrollment rates of minorities into biomedical research studies have found that minorities (largely Blacks and Hispanics) do enroll, proportionally, in clinical research at expected and targeted rates when a reasonable effort is made to enroll them. A report on the enrollment of minorities into the national Women’s Health Initiative Study (WHIS) stated that “the WHI achieved 93% of is targeted minority goal” (p. 342) and noted that “recruitment yields for [Black and Hispanic] minority groups surpassed that of white women” (p. 350).34 A recent review of 20 studies mat reported enrollment rates by race and ethnicity for over 70,000 individuals involving a wide range of biomedical studies (ranging from interview studies to drug treatment and surgical trials) reported that the researchers “found very small differences in the willingness of minorities, most of whom were Blacks and Hispanics in the U.S., to participate in health research compared to non-Hispanic whites” (p. 1) and concluded that “racial and ethnic minorities in the US, are as willing as non-Hispanic whites to participate in health research” (p. 1).36

Conclusion

An accurate understanding of the relative contributions of race and other factors that encourage or impede participation in biomedical research is crucial to the development of interventions and comprehensive recruitment strategies. The TLP Study was undertaken to provide information that could be used to improve recruitment and retention strategies for ongoing and future biomedical research. The findings from this report on the Tuskegee Legacy Project Study indicate that there is no difference between Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in self-reported willingness to participate in biomedical research, as measured by the Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale. However, while there was no detectable difference observed in the LOP Scale across racial/ethnic groups, the data show a statistically significant difference across the three racial/ethnic groups for the Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale, with Blacks being 1.8 times as likely as Whites to have a higher fear of participation in biomedical research. The combination of these two main findings leads to the conclusion that, although Blacks self-report having a higher fear of participation, they are just as likely as Whites to self-report willingness to participate in biomedical research. These findings are largely in keeping with the few similar studies on self-reported participation in the literature, and with the emerging literature that has assessed actual enrollment rates in biomedical studies by race and ethnicity.

Figure 1.

Percentage indicating willingness to participate in a medical study in a single gestatlt question (Q16) by race/ethnicity in the TLP Study.

Figure 2.

Percentage willing to participate in a medical research study dependent upon who was running the study by race/ethnicity in the TLP Study, N=1133.

Figure 3.

Percentage willing to participate in a medical research study dependent upon what one is asked to do in the study by race/ethnicity in the TLP Study, N= 1133.

Figure 4.

Guinea Pig Fear Factor (GPFF) Scale and Likelihood of Participation (LOP) Scale scores by race/ethnicity in the TLP Study, N= 1133.

Table 2.

ADJUSTED ANCOVA MULTIVARIATE ANALYSISa FOR THE GUINEA PIG FEAR FACTOR (GPFF) SCALE BY RACE/ETHNICITY IN THE TLP STUDY, N=1133

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean squares | F | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicityb,c | 5393.0 | 2 | 2746.5 | 3.8 | .022b |

| Age | 5443.3 | 1 | 5443.3 | 7.6 | .006 |

| Error | 790685.8 | 1098 | 720.1 |

Adjusted for age, sex, education, income, and city in Two-step bivariate, then multivariate, analysis.

For the GPFF Scale, race/ethnicity was statistically significant (p=.022)

A post hoc test, using the Bonferroni criterion, revealed Blacks with higher GPFF Scale scores as compared to Whites (p≤.05).

Table 3.

LOGISTIC REGRESSION MULTIVARIATE ANALYSISa FOR THE GUINEA PIG FEAR FACTOR (GPFF) SCALE BY RACE/ETHNICITY IN THE TLP STUDY, N= 1133

| Final model variables | df | p-value | Exp(ß) | Lower | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex(1) | 1 | .096 | 1.02 | .96 | 1.57 |

| Race/ethnicityb | 2 | .000 | |||

| Blacks | 1 | .000 | 1.79 | 1.36 | 2.37 |

| Hispanics | 1 | .251 | 1.28 | .54 | 1.94 |

| Age | 1 | .033 | .99 | .98 | .99 |

| Cityc | 3 | .115 | |||

| Birmingham, AL | 1 | .052 | .70 | .49 | 1.00 |

| Tuskegee, AL | 1 | .762 | 1.05 | .76 | 1.44 |

| San Antonio, TX | 1 | .657 | 1.09 | .75 | 1.57 |

| Constant | 1 | .707 | .92 |

Note: df—degrees of freedom

Adjusted for rate, age, sex, education, income, and city.

Reference groups: Whites

Hartford, CT

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express special thanks and deep gratitude to Michele Shedlin, PhD and Larry Shulman, MSW, nationally recognized leaders in focus group research, who gave unstintingly of their time and expertise in the early years of developing the TLP Questionnaire, and to Dr. Rueben Warren, former Dean of Meharry Medical College School of Dentistry and former Associate Director for Minority Health at CDC, who was so instrumental, at key junctions, in ensuring that this Tuskegee Legacy Project would progress and thrive. In addition, one of the true joys of this project, which has now spanned a decade, has been the excitement interjected into the research team each summer via the stream of 29 student summer researchers from 9 academic institutions (1 high school, 5 colleges, and 4 dental schools) who have contributed to this study. The authors wish to thank Mr. Tom Blocker, the pre-professional coordinator at Morehouse College, who was ‘the force’ in identifying student summer researchers from both Morehouse and Spelman Colleges over the many years. Finally, the authors wish to thank the following student researchers who worked so diligently, and with such high enthusiasm, during their summer pilot projects to either develop, test, or refine the core instrument used in this study, The Tuskegee Legacy Project (TLP) Questionnaire:

Simsbury High School: Lindsey Newitter

Central Connecticut State University: Steve Brofsky

Oakwood College: Leilani Britton

Morehouse College: Terrence Biscombe, Keith Camper, Michael Johnson

Spelman College: Siti Powers, Azure Cartwell, Courtney Whittaker, Allena Willis, Ayana Wilson

Vassar College: Ben Repenning

Howard University College of Dentistry: Eddie Brown

New York University College of Dentistry: Piotr Brzoza, Paul Chen, Margaret Funny, Jan Paul Gonzales, Michelle I Iaghpanah, Marcus Johnson, Ali Karimi, Marc Nock, Jai Park, Anne X. Truong

University of Connecticut School of Dental Medicine: Marya Barnes, Margaret Lipsky, Alpa Patel, Peter Wojtkiewcz

University of Puerto Rico School of Dentistry: Karim Morales, Reinaldo Rosas

The Tuskegee Legacy Project Study was supported by two NIDCR/NIH grants: 1) P50 DE10592, the Northeastern Minority Oral Health Research Center, a Regional Research Center for Minority Oral Health; and 2) U54 DE 14257, the NYU Oral Cancer RAAHP* Center (* = Research on Adult and Adolescent Health Promotion), an Oral Health Disparities Research Center.

References

- 1.Jones JH. Bad blood: the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. New York: Free Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee. Legacy Committee request. In: Reverby SM, editor. Tuskegee’s truths: rethinking the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2000. pp. 559–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell A. NY Times. Health; 1997. May 17, Clinton regrets “clearly racist” U.S. study. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunninghake DB, Darby CA, Probstfield JL. Recruitment experience in clinical trials: literature summary and annotated bibliography. Control Clin Trials. 1987 Dec;8(4 Suppl):6S–30S. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(87)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson MS, Ward AJ. Recruiting minorities into clinical trials: toward a participant-friendly system. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995 Dec 6;87(23):1747–59. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.23.1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, 1932 to 1972: implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. Am J Public Health. 1991 Nov;81(11):1498–505. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kressin NR, Meterko M, Wilson NJ. Racial disparities in biomedical research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000 Feb;92(2):62–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister, et al. Why are African Americans under-represented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethn Health. 1997 Mar;2(1–2):31–45. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1997.9961813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamble VN. A legacy of distrust: African Americans and medical research. Am J Prev Med. 1993 Nov–Dec;9(6 Suppl):35–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caplan AL. Twenty years after. The legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. When evil intrudes. Hastings Cent Rep. 1992 Nov–Dec;22(6):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benedek TG. The Tuskegee Study of syphilis: analysis of moral versus methodologic aspects. J Chron Dis. 1978 Jan;31(1):35–50. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(78)90079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corbie-Smith GM. Minority recruitment and participation in health research. N C Med J. 2004 Nov–Dec;6(6):385–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gamble VN. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and women’s health. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1997 Fall;52(4):195–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews AK, Sellergren SA, Manfredi C, et al. Factors influencing medical information seeking among African American cancer patients. J Health Commun. 2002 May–Jun;7(3):205–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730290088094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pressel DM. Nuremberg and Tuskegee: lessons for contemporary American medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003 Dec;95(12):1216–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rathore SS, Krumholz HM. Race, ethnic group, and clinical research. BMJ. 2003 Oct 4;327(7418):763–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7418.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouleware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Pub Health Rep. 2003 Jul–Aug;118(4):358–65. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandon DT, Issac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust ill medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Jul;97(7):951–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White RM. Misinformation and misbeliefs in the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis fuel mistrust in the healthcare system. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Nov;97(11):1566–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairchild AL, Bayer R. Uses and abuses of Tuskegee. Science. 1999 May;284(5416):919–21. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5416.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.“Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and its Legacy”. Symposium; Charlottesville (VA). February 23, 1994; Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Center for Bioethics and UVA Library Historical Collections; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reverby SM. Introduction. More than a metaphor: an overview of the scholarship of the study. In: Reverby SM, editor. Tuskegee’s truths: rethinking the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2000. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999 Sep;14(9):537–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green BL, Partridge EE, Fouad MN, et al. African-American attitudes regarding cancer clinical trials and research studies: results from focus group methodology. Ethn Dis. 2000 Winter;10(1):76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, et al. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Soc Sci Med. 2001 Mar;52(5):797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates BR, Harris TM. The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis and public perceptions of biomedical research: a focus group study. J Nat Med Assoc. 2004 Aug;96(8):1051–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengupta S, Strauss RP, DeVellis R, et al. Factors affecting African-American participation in AIDS research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000 Jul;24(3):275–84. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200007010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown DR, Topcu M. Willingness to participate in clinical treatment research among older African Americans and Whites. Gerontologist. 2003 Feb;43(1):62–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green BL, Maisiak R, Wang MQ, et al. Participation in health education, health promotion, and health research by African Americans: Effects of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. J Health Educ. 1997;28(4):196–201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee sudy and its impact on willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000 Dec;92(12):563–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Green BL, et al. The Tuskegee Legacy Project; history, preliminary scientific findings, and unanticipated societal benefits. Dent Clin North Am. 2003 Jan;47(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(02)00049-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institutes of Health. NIH guidelines on inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. NIH Guide. 1994 Mar 18;23(11) Available at http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/not94-100.html.

- 33.Hays RD, Hayashi T. A RAND Note. (Doc. No. N-3155-RC) Los Angeles, CA: RAND Corporation; 1990. Beyond internal consistency: rationale and users’ guide for Multitrait Analysis Program on the microcomputer. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hays RD, Hayashi T, Carson S, et al. A Rand Note (Doc. No. N-2786-RC) Los Angeles, CA: RAND Corporation; 1988. User’s guide for the Multitrait Analysis Program (MAP) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campbell DT, Fiske DW. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol Bull. 1959 Mar;56(2):81–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fouad MN, Corbie-Smith G, Curb D, et al. Special populations recruitment for the Women’s Health Initiative: successes and limitations. Control Clin Trials. 2004 Aug;25(4):335–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006 Feb;3(2):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]