Abstract

It is well documented that leptin is a circulating hormone that plays a key role in regulating food intake and body weight via its actions on specific hypothalamic nuclei. However leptin receptors are widely expressed in the CNS, in regions not generally associated with energy homeostasis, such as the hippocampus, cortex and cerebellum. Moreover, evidence is accumulating that leptin has widespread actions in the brain. In particular, recent studies have demonstrated that leptin markedly influences the excitability of hippocampal neurons, via its ability to activate large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels, and also to promote long-term depression (LTD) of excitatory synaptic transmission. Here we review the evidence supporting a role for this hormone in regulating hippocampal excitability.

Keywords: leptin, large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, actin dynamics, hyper-excitability, long-term depression, PI 3-kinase

Introduction

Leptin

The hormone leptin is a highly conserved 167 amino acid protein that is encoded by the obese (ob) gene (Zhang et al 1994). It is predominantly, although not exclusively synthesized by adipocytes and it circulates in the plasma in amounts proportional to body fat content (Maffei et al, 1995; Considine et al, 1996). Leptin displays a high degree of homology amongst different species and it is also analogous in structure to other cytokines (Madej et al, 1995). It was first identified by its ability to regulate food intake and body weight via its actions in the hypothalamus (Jacob et al, 1997; Spiegelman and Flier, 2001). However recent studies have shown that the neuronal actions of leptin are not confined to the hypothalamus. Indeed evidence is accumulating that this hormone has widespread biological actions in the central nervous system.

Leptin receptor

Expression cloning techniques were initially performed by Tartaglia et al (1995) to isolate the leptin receptor (Ob-R) from mouse choroid plexus. Ob-R was found to be encoded by the diabetes (db) locus located within the 5.1 cM interval of mouse chromosome 4 (Tartaglia et al, 1995). The leptin receptor shows greatest homology to the class I cytokine superfamily of receptors which are characterised by extracellular motifs of four cysteine residues and a number of fibronectin type III domains (Heim, 1996). The leptin receptor is known to exist as a homodimer and is activated by conformational changes that occur following ligand binding to the receptor (Devos et al, 1997).

Six leptin receptor isoforms, generated by alternate slicing of the db gene, have been identified so far (Wang et al, 1998; Lee et al, 1996). These isoforms, termed Ob-Ra to Ob-Rf, have identical extracellular N-terminal domains comprising of over 800 amino acids, but have distinct intracellular C-terminal regions. All the leptin receptor isoforms, except Ob-Re (Lee et al, 1997), are membrane spanning receptors that contain a 34 amino acid trans-membrane region. Ob-Re is distinct from the other isoforms and is thought to be a soluble form of the receptor as it is the predominant leptin binding site in the plasma. The remaining isoforms can be classed as either short isoforms (Ob-Ra, c, d and f) with a C-terminal domain of 30–40 residues, or the long isoform (Ob-Rb) with an intracellular domain comprising 302 amino acids in length.

Neuronal leptin receptor expression

High levels of leptin receptor mRNA and protein are expressed in both rodent and human hypothalamus (Hakansson et al, 1998; Schwartz et al, 1996; Elmquist et al, 1998; Savioz et al, 1997). In particular specific hypothalamic nuclei (ventromedial hypothalamus, arcuate nucleus and dorsomedial hypothalamus) that are involved in regulating energy homeostasis are highly enriched with leptin receptors. Leptin receptor mRNA and immunoreactivity are also highly expressed in many extra-hypothalamic brain regions including hippocampus, brain stem, cerebellum, amygdala and substantia nigra (Mercer et al, 1996; Hakansson et al, 1998; Elmquist et al, 1998; Grill et al, 2002; Figlewicz et al, 2003). In the hippocampus, the distribution of leptin receptor immunoreactivity has been well characterised, and the CA1/CA3 and dentate gyrus regions exhibit high levels of leptin receptor mRNA and immunolabelling (Mercer et al, 1996; Shanley et al, 2002a). Moreover in primary hippocampal cultures, dual-labelling approaches have shown that leptin receptor immunoreactivity is found on axonal processes and somato-dendritic regions (Shanley et al, 2002a). It is also highly expressed at hippocampal synapses (Shanley et al, 2002a) suggesting a possible role for this hormone in modulating synaptic function in this brain region.

Transport of leptin into the brain

Leptin is thought to enter the brain via two distinct mechanisms. A saturable transport system is thought to enable leptin to cross the blood brain barrier via receptor-mediated transcytosis (Banks et al, 1996). Indeed, the short leptin receptor isoforms, which are capable of binding and internalizing leptin, have been detected on brain microvessels (Bjorbaek et al, 1998a; Golden et al, 1997). In mice impairments in leptin transport across the blood brain barrier develop in tandem with obesity; a process that can be reversed by modest weight reduction (Banks et al, 2003). Moreover, recent studies have also shown that leptin transport is regulated by epinephrine (Banks, 2001) and triglycerides (Banks et al, 2004). Leptin is also likely to be transported to the brain via the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF; Schwartz et al, 1996), as the choroid plexus, the key site for production of CSF, expresses high levels of Ob-Ra and could mediate transport of leptin from the blood to the CSF (Bjorbaek et al, 1998a). In addition, leptin has the potential to be made and released locally in the CNS. In support of this possibility leptin mRNA and immunoreactivity are widely expressed throughout the brain (Morash et al, 1999; Ur et al, 2002). Thus, like other neuropeptides such as oxytocin and vasopressin (Ludwig & Pittman, 2003), leptin may be released from neuronal dendrites and signal in a retrograde manner to modulate neuronal function. However in the absence of evidence supporting dendritic release of leptin, it is likely that peripherally-derived leptin has the ability to modulate hippocampal function. Indeed, Banks et al (2000) have shown that leptin can be transported across the blood brain barrier to all brain regions. Furthermore, the expression levels of glucocorticoids in the hippocampus are markedly altered following intraperitoneal administration of leptin (Proulx et al, 2001).

Leptin receptor-dependent signaling pathways

The leptin receptor is a class I cytokine receptor (Tartaglia et al, 1995) that activates analagous signaling cascades to other members of this receptor superfamily such as interleukin 6 and leukemia-inhibitory factor receptors (Ihle, 1995). Thus, following leptin binding and subsequent receptor activation, janus tyrosine kinases (JAKs), and in particular JAK2 (Baumann et al, 1996; Bjorbaek et al, 1997), are activated. JAK2 then associates with specific C-terminal domains of the leptin receptor which results in trans-phosphorylation of JAK2 and subsequent phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues located within the C-terminal domain. This chain of events in turn acts as a catalyst to enable the recruitment and activation of various downstream signaling molecules including STAT (signal transducers and activators of transcription) transcription factors, insulin receptor substrate (IRS) proteins, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) and the Ras-Raf-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling pathway (see Hegyi et al, 2004, Harvey, 2003 for reviews).

The long form of the leptin receptor (Ob-Rb) is thought to be the predominant signaling competent isoform due to the expression of various signaling motifs within its C-terminal domain, and the inability of the short leptin receptor isoforms to undergo tyrosine phosphorylation (Bjorbaek et al, 1998b). However, the short isoforms are capable of signaling in some cell types. For instance, the MAPK signaling cascade is stimulated following activation of recombinant Ob-Ra expressed in either CHO or HEK293 cells (Bjorbaek et al, 1998b; Yamashita et al, 1998). Furthermore, in hepatocytes, that fail to express the signaling competent Ob-Rb, leptin still has the ability to inhibit the effects of glucagon (Zhao et al, 2000).

Modulation of hippocampal function by leptin

1. Regulation of hippocampal excitability

Previous studies have demonstrated that leptin inhibits peripheral insulin-secreting cells (Harvey et al 1997), glucose-responsive hypothalamic neurons (Spanswick et al, 1997) and nucleus tractus solitarius neurons (Williams & Smith, 2006) via activation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels. Similarly leptin inhibits rat hippocampal neurons by increasing a K+ conductance (Shanley et al, 2002a), but in contrast to these other cell types, KATP channels are not the cellular target for leptin in hippocampal neurons. Thus, the leptin-induced hyperpolarisation and increased K+ conductance were inhibited by the Ca2+ and voltage-dependent K+ channel blocker, TEA, but not the sulphonylurea, tolbutamide (Shanley et al, 2002a). Moreover, in single channel recordings leptin increased the activity of a charybdotoxin-sensitive K+ channel, consistent with the activation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels (Shanley et al, 2002a). It is well documented that BK channels consist of a pore forming α subunit (Slo) with or without a regulatory β subunit (Toro et al, 1998). In HEK293 cells expressing either hSlo or hSlo + hSloβ1, together with Ob-Rb, application of leptin via the patch pipette evoked a rapid increase in BK channel activity. As leptin was capable of altering BK channel activity in HEK293 cells expressing only the α subunit, it is likely that β subunits are not a prerequisite for this effect of leptin. In support of this, the effects of leptin were blocked by low nanomolar concentration of charybdotoxin (Shanley et al, 2002a,b), even though expression of the BK channel β4 subunit, the predominant β subunit in the CNS (Behrens et al, 2000), reduces the sensitivity of BK channels to iberiotoxin and charybdotoxin (Behrens et al, 2000; Meera et al, 2000).

The ability of leptin to modulate BK channel activity involved a PI 3-kinase driven mechanism as the effects of leptin were inhibited or reversed by the PI 3-kinase inhibitor wortmannin (Shanley et al, 2002a,b). More recent studies have shown that a complex series of events downstream of PI 3-kinase couple leptin receptors to rapid alterations in the actin cytoskeleton and subsequent stimulation of BK channels (O’Malley et al, 2005). This process shows parallels to leptin’s effects on hypothalamic neurons and insulinoma cells, as its ability to modulate KATP channel function also depends on PI 3-kinase-dependent re-organisation of actin filaments(Harvey et al, 2000; Mirshamsi et al 2004). However in hypothalamic neurons and insulinoma cells, the precise identity of the intermediate signaling molecules linking PI 3-kinase activity to alterations in actin dynamics is unknown. In hippocampal neurons, leptin receptor-driven activation of PI 3-kinase has been shown to result in a rapid and highly localised increase in the levels of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 at synapses, which promotes the depolymerisation and re-organisation of actin filaments. This in turn results in the activation and clustering of BK channels at hippocampal synapses (O’Malley et al, 2005). However it is unclear how the elevations in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels influence actin dynamics in hippocampal neurons. As PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 can activate Rho GTPases, which play a key role in regulating actin dynamics, it is feasible that leptin influences the actin cytoskeleton by modifying Rho GTPase activity (Attoub et al, 2000). Alternatively, PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 may directly bind to and alter the activity of actin binding proteins thereby influencing actin dynamics (Janmey, 1999). The decrease in the levels of the PI 3-kinase substrate, PtdIns(4,5)P2, that occurs following PI 3-kinase activation, may also trigger changes in actin dynamics as PtdIns(4,5)P2 is known to associate with and modulate various cytoskeletal proteins (Janmey, 1999).

In hippocampal neurons, BK channel activation results in generation of the fast afterhyperpolarisation, which is in turn responsible for repolarisation of action potentials. Thus BK channels are likely to play a key role in determining action potential firing rates and burst firing patterns. Thus, it is conceivable that BK channel activation by leptin regulates the level of hippocampal excitability. Indeed in a Mg2+-free culture model of epileptiform-like activity, application of leptin induced a rapid and reversible attenuation of the enhanced global levels of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i; Shanley et al, 2002b). In contrast, leptin failed to alter the basal levels of [Ca2+]i in control conditions. The effects of leptin on this model of epileptiform-like activity were mimicked by a selective BK channel opener, NS 1619, but were occluded by either iberiotoxin or charybdotoxin, indicating that leptin-induced activation of BK channels underlies this process. Moreover in parallel with the signaling pathways coupling leptin receptors to stimulation of single BK channels, a PI 3-kinase-, but not MAPK-, dependent signaling cascade underlies this process.

In another model of epileptiform-like activity, acute hippocampal slices were bathed in Mg2+-free medium and subsequent application of leptin reduced the frequency of interictal discharges (Shanley et al, 2002a). Leptin receptor activation underlies this process as leptin inhibited the interictal discharge frequency in slices from Zucker lean, but not obese fa/fa rats (Shanley et al 2002a). It is interesting to note that in Mg2+-free conditions the frequency of interictal events was significantly higher in slices from Zucker fa/fa rats than in age-matched lean controls, suggesting that rodents that are insensitive to leptin also have an increased level of neuronal excitability. Moreover, the ability of leptin to modulate the excitability is not confined to the hippocampus, as leptin can also markedly influence the firing frequency of hypothalamic neuropeptide Y (NPY)/Agouti-related protein (AgRP) neurons (Takahashi & Cone, 2005). Thus fasting which reduces the circulating levels of leptin, resulted in an increase in the spike frequency of NPY neurons whereas direct administration of leptin into the hypothalamus reduced the spike frequency in fasted animals (Takahashi & Cone, 2005). In contrast, leptin is reported to increase the frequency of penicillin-evoked epileptic discharges in the somatomoter cortex, suggesting that leptin may have pro-convulsant activity in this brain region (Ayyildiz et al, 2006).

It is well established that unregulated hyper-excitability in the hippocampus is associated with the onset of temporal lobe epilepsy. It is also known that despite intensive antiepileptic drug research and development, many individuals with this and other forms of epilepsy display resistance to standard drug therapies. However several lines of evidence indicate that the incidence and manageability of seizures can be markedly improved by moderate changes in energy homeostasis with diets such as fasting, the ketogenic diet and calorie restriction (Greene et al, 2003). This has led to the hypothesis that metabolic disturbances may influence the severity and frequency of epileptic seizures. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that alterations in the circulating levels of the metabolic hormone leptin may be one of many factors contributing to these disturbances in energy balance in epilepsy and which may in turn influence neuronal excitability.

Leptin induces a novel form of NMDA receptor-dependent LTD

In addition to its effects on hippocampal neuronal excitability, under conditions of enhanced excitability leptin also markedly alters the strength of excitatory synaptic transmission. Thus following removal of Mg2+ or blockade of GABAA receptors, leptin induced a novel form of hippocampal long-term depression (LTD; Durakoglugil et al, 2005). This contrasts with the actions of leptin under physiological conditions (1 mM Mg2+), as it promotes the induction of hippocampal long term potentiation (LTP; Shanley et al, 2001; Wayner et al, 2004), via facilitating NMDA receptor function (Shanley et al, 2001). Recent studies have suggested that activation of NR2A containing NMDA receptors is required for the induction of LTP whereas NR2B subunit activation promotes LTD induction (Massey et al, 2004; Liu et al, 2004). Thus, the ability of leptin to bi-directionally modulate the strength of hippocampal excitatory synaptic transmission may reflect differential effects of this hormone on NMDA receptor subunits under different levels of excitability. In support of this possibility leptin is reported to preferentially enhance NR2B-mediated NMDA responses in cerebellar granule cells (Irving et al, 2006).

The LTD induced by leptin in the CA1 region of the hippocampus was inhibited by the competitive NMDA receptor antagonist D-APV, but not by group 1a and group 5 metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) antagonists, indicating that this form of LTD is NMDA-, but not mGluR-dependent. Moreover, leptin-induced LTD shares at least some similar expression mechanisms to LTD induced by low frequency-induced stimulation (LFS) as leptin did not reduce synaptic responses further following saturation of LFS-induced LTD, whereas LFS still depressed synaptic transmission after leptin-induced LTD (Durakoglugil et al, 2005). Leptin-induced LTD is likely to be expressed postsynaptically as the synaptic depression induced by leptin was not accompanied by a change in the corresponding paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) ratio. In contrast, the depression evoked by adenosine, which is known to act presynaptically, was paralleled by a significant change in the PPF ratio.

Durakoglugil et al (2005) also evaluated the signaling pathways underlying leptin-induced LTD and demonstrated that inhibition of PI 3-kinase failed to attenuate, but rather markedly enhanced the level of depression induced by leptin. This suggests that leptin-induced LTD is negatively regulated by PI 3-kinase. Similarly inhibition of serine/threonine protein phosphatases 1/2A, but not protein phosphatase 2B, enhanced the depressant effects of leptin. The negative regulation of leptin-induced LTD by PI 3-kinase is in marked contrast to the role of this enzyme in hippocampal LTP as the ability of leptin to facilitate NMDA receptor-dependent LTP is PI 3-kinase-dependent (Shanley et al, 2001). Thus, these data indicate that the ability of leptin to influence different forms of hippocampal synaptic plasticity not only occurs under differential conditions, but also that divergent leptin receptor-driven signaling cascades mediate these processes.

Conclusions

There is growing evidence that, in addition to its role in regulating energy balance, the hormone leptin has widespread actions in the CNS (Fig 2). In the hippocampus, leptin is a potent regulator of neuronal excitability as it has the ability to inhibit epileptiform-like activity via a process involving PI 3-kinase-driven activation of BK channels (Shanley et al, 2002a,b). Under conditions of enhanced excitability, leptin also promotes a long lasting inhibition (LTD) of excitatory synaptic strength; a process that is negatively regulated by PI 3-kinase (Durakoglugil et al, 2005). The ability of leptin to markedly alter the excitability of hippocampal neurons via both synaptic and non-synaptic mechanisms may have important implications for the role of this hormone in regulating hippocampal hyper-excitability.

Figure 2. Diverse neuronal actions of leptin.

Schematic representation of the key brain functions that are regulated by the hormone leptin. Leptin that is derived from adipocytes circulates in the plasma in amounts proportional to body weight and it can enter the brain via saturable transport across the blood brain barrier. The arcuate nucleus, an important component of hypothalamic feeding circuits, is a key target for leptin and in normal weight humans and animals this hormone acts as a signal to the brain to cease eating. Leptin also plays a pivotal role in regulating reproductive function and thermogenesis via its actions on this hypothalamic nucleus. Several lines of evidence also support a role for leptin in hippocampal learning and memory processes as leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and facilitates hippocampal long-term potentiation. Moreover in behavioural studies leptin-insensitive rodents display memory impairments whereas leptin administration improves memory performance. In the hippocampus, leptin also regulates neuronal excitability via its ability to activate BK channels; a process that may be an important mechanism for dampening down unregulated hyper-excitability. In cerebellar neurons, NMDA receptors are also an important target for leptin as facilitation of NR2B-mediated NMDA responses has been reported.

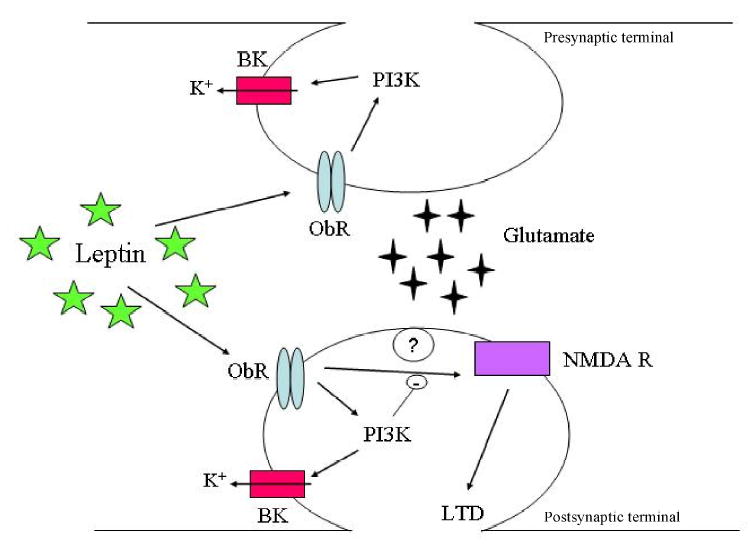

Figure 1. Leptin attenuates hippocampal excitability via synaptic and non-synaptic mechanisms.

Schematic representation of a typical CA1 glutamatergic excitatory synapse and that illustrates the possible mechanisms underlying the effects of leptin on neuronal excitability. Leptin receptors (ObR) are located at both presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in hippocampal neurons. Leptin receptor activation results in phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase)-dependent actin depolymerisation and subsequent stimulation of large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels. This in turn results in inhibition of epileptiform-like activity. Under conditions of enhanced excitability, leptin also markedly reduces the strength of excitatory synaptic transmission by promoting the induction of NMDA receptor (NMDA R)-dependent long-term depression (LTD). This process has a postsynaptic locus of expression and is negatively regulated by PI 3-kinase.

References

- Attoub S, Noe V, Pirola L, Bruyneel E, Chastre E, Mareel M, Wymann MP, Gespach C. Leptin promotes invasiveness of kidney and colonic epithelial cells via phosphoinositide 3-kinase-, rho-, and rac-dependent signaling pathways. FASEB J. 2000;14:2329–38. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyildiz M, Yildirim M, Agar E, Baltaci AK. The effect of leptin on penicillin-induced epileptiform-like activity in rats. Brain Res Bull. 2006;68:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA. Enhanced leptin transport across the blood brain barrier by alpha 1-adrenergic agents. Brain Res. 2001;899:209–17. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Clever CM, Farrell CL. Partial saturation and regional variation in the blood-to-brain transport of leptin in normal weight mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E1158–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.6.E1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Coon AB, Robinson SM, Moinuddin A, Shultz JM, Nakaoke R, Morley JE. Triglycerides induce leptin resistance at the blood brain barrier. Diabetes. 2004;53:1253–60. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.5.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Farrell CL. Impaired transport of leptin across the blood brain barrier in obesity is acquired and reversible. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E10–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00468.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks WA, Kastin AJ, Huang W, Jaspan JB, Maness LM. Leptin enters the brain by a saturable system independent of insulin. Peptides. 1996;17:305–11. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(96)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Morella KK, White DW, Dembski M, Bailon PS, Kim H, Lai CF, Tartaglia LA. The full-length leptin receptor has signaling capabilities of interleukin 6-type cytokine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8374–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorbaek C, Elmquist JK, Michl P, Ahima RS, van Bueren A, McCall AL, Flier JS. Expression of leptin receptor isoforms in rat brain microvessels. Endocrinology. 1998a;139:3485–91. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.8.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorbaek C, Uotani S, da Silva B, Flier JS. Divergent signaling capacities of the long and short isoforms of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32686–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorbaek C, Uotani S, da Silva B, Flier JS. Divergent signaling capacities of the long and short isoforms of the leptin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998b;272:32686–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Considine RV, Considine EL, Williams CJ, Hyde TM, Caro JF. The hypothalamic leptin receptor in humans: identification of incidental sequence polymorphisms and absence of the db/db mouse and fa/fa rat mutations. Diabetes. 1996;45:992–4. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.7.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos R, Guisez Y, Van der Heyden J, White DW, Kalai M, Fountoulakis M, Plaetinck G. Ligand-independent dimerization of the extracellular domain of the leptin receptor and determination of the stoichiometry of leptin binding. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18304–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Bjorbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:535–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlewicz DP, Evans SB, Murphy J, Hoen M, Baskin DG. Expression of receptors for insulin and leptin in the ventral tegmental area/substantia nigra (VTA/SN) of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;964:107–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden PL, Maccagnan TJ, Pardridge WM. Human blood-brain barrier leptin receptor. Binding and endocytosis in isolated human brain microvessels. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:14–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene AE, Todorova MT, Seyfried TN. Perspectives on the metabolic management of epilepsy through dietary reduction of glucose and elevation of ketone bodies. J Neurochem. 2003;86:529–537. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill HJ, Schwartz MW, Kaplan JM, Foxhall JS, Breininger J, Baskin DG. Evidence that the caudal brainstem is a target for the inhibitory effect of leptin on food intake. Endocrinology. 2002;143:239–46. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.1.8589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson ML, Brown H, Ghilardi N, Skoda RC, Meister B. Leptin receptor immunoreactivity in chemically defined target neurons of the hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:559–72. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00559.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J. Leptin: a multifaceted hormone in the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;28:245–58. doi: 10.1385/MN:28:3:245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey J, McKenna F, Herson PS, Spanswick D, Ashford ML. Leptin activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the rat insulin-secreting cell line, CRI-G1. J Physiol. 1997;504:527–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.527bd.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegyi K, Fulop K, Kovacs K, Toth S, Falus A. Leptin-induced signal transduction pathways. Cell Biol Int. 2004;28:159–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim MH. The Jak-STAT pathway: specific signal transduction from the cell membrane to the nucleus. Eur J Clin Invest. 1996;26:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1996.103248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle JN. Cytokine receptor signalling. Nature. 1995;377:591–4. doi: 10.1038/377591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving AJ, Wallace L, Durakoglugil D, Harvey J. Leptin enhances NR2B-mediated N-methyl-D-aspartate responses via a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent process in cerebellar granule cells. Neurosci. 2006;138(4):1137–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob RJ, Dziura J, Medwick MB, Leone P, Caprio S, During M, Shulman GI, Sherwin RS. The effect of leptin is enhanced by microinjection into the ventromedial hypothalamus. Diabetes. 1997;46:150–2. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janmey PA, Xian W, Flanagan LA. Controlling cytoskeleton structure by phosphoinositide-protein interactions: phosphoinositide binding protein domains and effects of lipid packing. Chem Phys Lipids. 1999;101:93–107. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(99)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Li C, Montez J, Halaas J, Darvishzadeh J, Friedman JM. Leptin receptor mutations in 129 db3J/db3J mice and NIH facp/facp rats. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:445–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GH, Proenca R, Montez JM, Carroll KM, Darvishzadeh JG, Lee JI, Friedman JM. Abnormal splicing of the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Nature. 1996;379:632–5. doi: 10.1038/379632a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Wong TP, Pozza MF, Lingenhoehl K, Wang Y, Sheng M, Auberson YP, Wang YT. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in governing the direction of hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Science. 2004;304:1021–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1096615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig M, Pittman QJ. Talking back: dendritic neurotransmitter release. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:255–61. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madej T, Boguski MS, Bryant SH. Threading analysis suggests that the obese gene product may be a helical cytokine. FEBS Lett. 1995;373:13–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00977-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, Pratley RE, Lee GH, Zhang Y, Fei H, Kim S, Lallone R, Ranganathan S, et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med. 1995;1:1155–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey PV, Johnson BE, Moult PR, Auberson YP, Brown MW, Molnar E, Collingridge GL, Bashir ZI. Differential roles of NR2A and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in cortical long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7821–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1697-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer JG, Hoggard N, Williams LM, Lawrence CB, Hannah LT, Trayhurn P. Localization of leptin receptor mRNA and the long form splice variant (Ob-Rb) in mouse hypothalamus and adjacent brain regions by in situ hybridization. FEBS Lett. 1996;387:113–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00473-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morash B, Li A, Murphy PR, Wilkinson M, Ur E. Leptin gene expression in the brain and pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5995–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley D, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin-induced dynamic alterations in the actin cytoskeleton mediate the activation and synaptic clustering of BK channels. FASEB J. 2005;19:1917–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4166fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx K, Clavel S, Nault G, Richard D, Walker CD. High neonatal leptin exposure enhances brain GR expression and feedback efficacy on the adrenocortical axis of developing rats. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4607–16. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savioz A, Charnay Y, Huguenin C, Graviou C, Greggio B, Bouras C. Expression of leptin receptor mRNA (long form splice variant) in the human cerebellum. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3123–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199709290-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Peskind E, Raskind M, Boyko EJ, Porte D., Jr Cerebrospinal fluid leptin levels: relationship to plasma levels and to adiposity in humans. Nat Med. 1996;2:589–93. doi: 10.1038/nm0596-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Campfield LA, Burn P, Baskin DG. Identification of targets of leptin action in rat hypothalamus. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1101–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI118891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley LJ, Irving AJ, Harvey J. Leptin enhances NMDA receptor function and modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley LJ, Irving AJ, Rae MG, Ashford ML, Harvey J. Leptin inhibits rat hippocampal neurons via activation of large conductance calcium-activated K+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2002b;5:299–300. doi: 10.1038/nn824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanley LJ, O'Malley D, Irving AJ, Ashford ML, Harvey J. Leptin inhibits epileptiform-like activity in rat hippocampal neurones via PI 3-kinase-driven activation of BK channels. J Physiol. 2002a;545:933–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.029488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick D, Smith MA, Groppi VE, Logan SD, Ashford ML. Leptin inhibits hypothalamic neurons by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Nature. 1997;390:521–5. doi: 10.1038/37379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman BM, Flier JS. Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell. 2001;104:531–43. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi KA, Cone RD. Fasting induces a large, leptin-dependent increase in the intrinsic action potential frequency of orexigenic arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y/Agouti-related protein neurons. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1043–1047. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia LA, Dembski M, Weng X, et al. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB-R. Cell. 1995;83:1263–71. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro L, Wallner M, Meera P, Tanaka Y. Maxi-K(Ca), a Unique Member of the Voltage-Gated K Channel Superfamily. News Physiol Sci. 1998;13:112–117. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.3.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ur E, Wilkinson DA, Morash BA, Wilkinson M. Leptin immunoreactivity is localized to neurons in rat brain. Neuroendocrinol. 2002;75:264–72. doi: 10.1159/000054718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu R, Hawkins M, Barzilai N, Rossetti L. A nutrient-sensing pathway regulates leptin gene expression in muscle and fat. Nature. 1998;393:684–8. doi: 10.1038/31474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayner MJ, Armstrong DL, Phelix CF, Oomura Y. Orexin-A (Hypocretin-1) and leptin enhance LTP in the dentate gyrus of rats in vivo. Peptides. 2004;25:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KW, Smith BN. Rapid inhibition of neural excitability in the nucleus tractus solitarii by leptin: implications for ingestive behaviour. J Physiol. 2006 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106336. 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T, Murakami T, Otani S, Kuwajima M, Shima K. Leptin receptor signal transduction: OBRa and OBRb of fa type. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;246:752–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–32. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao AZ, Shinohara MM, Huang D, Shimizu M, Eldar-Finkelman H, Krebs EG, Beavo JA, Bornfeldt KE. Leptin induces insulin-like signaling that antagonizes cAMP elevation by glucagon in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11348–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]