Abstract

Heat shock proteins are highly conserved proteins that, when produced intracellularly, protect stress exposed cells. In contrast, extracellular Hsp70 has been shown to have both protective and deleterious effects. In this study, we assessed heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) for its potential role in human longevity. Because of the importance of HSP to disease processes, cellular protection, and inflammation, we hypothesized that: (1) Hsp70 levels in centenarians and centenarian offspring are different from controls and (2) alleles in genes associated with Hsp70 explain these differences. In this cross-sectional study, we assessed serum Hsp70 levels from participants enrolled in either the New England Centenarian Study (NECS) or the Longevity Genes Project (LGP): 87 centenarians (from LGP), 93 centenarian offspring (from NECS), and 126 controls (43 from NECS, 83 from LGP). We also examined genotypic and allelic frequencies of polymorphisms in HSP70-A1A and HSP70-A1B in 347 centenarians (266 from the NECS, 81 from the LGP), 260 NECS centenarian offspring, and 238 controls (NECS: 53 spousal controls and 106 septuagenarian offspring controls; LGP: 79 spousal controls). The adjusted mean serum Hsp70 levels (ng/mL) for the NECS centenarian offspring, LGP centenarians, LGP spousal controls, and NECS controls were 1.05, 1.13, 3.05, 6.93, respectively, suggesting that a low serum Hsp70 level is associated with longevity; however, no genetic associations were found with two SNPs within two hsp70 genes.

Keywords: ageing, centenarian, chaperokine, heat shock proteins, longevity

1. Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are highly conserved proteins that function by chaperoning, transporting, and folding proteins when cells are exposed to a variety of stresses. Normally, HSP is expressed at low levels within all known cells; however, in response to various stressful conditions, a self-protective reaction occurs resulting in the synthesis of intracellular HSPs (Lindquist et al., 1988; Villar et al., 1993). One particular HSP, the inducible 70-kd heat shock protein (Hsp70), preserves cell viability by binding to polypeptide chains and preventing protein denaturation and incorrect assembly intracellularly (Georgopoulos et al., 1993; Hartl 1996). Intracellular Hsp70 is also thought to exert an anti-apoptotic function by binding to the tumor suppressor protein p53 and the cellular transcription factor, c-myc, thereby inhibiting the activation of the caspase cascade (Pinhasi-Kimhi et al., 1986; Koskinen et al., 1991).

Although the numerous functions of intracellular Hsp70 have been elucidated, only recently has the role of extracellular Hsp70 (also referred to as serum Hsp70) begun to be addressed. Accumulating evidence indicates that extracellular Hsp70 activates innate immune cells leading to an inflammatory cascade. Prior research has shown that extracellular Hsp70 possesses potent cytokine activity, with the ability to bind with high affinity to the plasma membrane, elicit a rapid intracellular Ca2+ flux, activate the transcription factor NF-κB nuclear translocation, augment the expression and release of pro- inflammatory cytokines (Basu et al.,1998; Asea et al., 2000; Asea et al., 2000; Binder et al., 2000), induce nitric oxide release (Panjwani et al., 2002), upregulate co-stimulatory molecule expression (Asea et al., 2002), and induce dendritic cell maturation (Kuppner et al., 2001; Asea et al., 2002; Noessner et al., 2002). These functions can be protective if activated in the context of a cellular insult; however, they can also be detrimental if they lead to excessive inflammation.

Various studies have examined the relationship of extracellular Hsp70 with aging. In their cross-sectional study, Rea et al (Rea et al., 2001) examined serum Hsp70 in 60 individuals with ages ranging from 20 to 96 years. They demonstrated a progressive decline in serum Hsp70 levels in older age groups. Similarly, Jin et al (Jin et al., 2004), in their study of 327 healthy male donors aged between 15 and 50 years, demonstrated a decline in serum Hsp70 at older ages (between 30 and 50) although at younger ages, they noted a positive correlation with age. These findings suggest that serum Hsp70 levels decline at older ages although they do not indicate whether levels decline over time within an individual. They also do not indicate whether there is a decline in Hsp70 function over time although in vitro studies suggest that cell lines from centenarians, when exposed to heat stress, have similar Hsp70 synthesis (Marini et al., 2004), have a similar transcriptional response to the hsp70 gene (Ambra et al., 2004), and are less prone to heat-induced apoptosis when compared to cell lines from younger individuals.

In this study we analyzed serum Hsp70 levels in a sample of centenarian subjects, their offspring, and unrelated controls. Because of the importance of HSP to disease processes, cellular protection, and inflammation, we hypothesized that (1) Hsp70 levels in centenarians and centenarian offspring are different from controls and (2) alleles in genes associated with Hsp70 explain these differences.

Few studies have examined the role of genetics in the relationship between Hsp70 and survival to very old age. Altomare et al (Altomare et al., 2003) found that a polymorphism within the hsp70 gene promoter was associated with longevity only in females. Subsequently, Marini et al (Marini et al., 2004) reported that in centenarians, the A/A genotype of the (A/C)-110 genetic polymorphism in the promoter region was associated with a lower expression of Hsp70 protein after heat stress, in comparison to the C/C genotype. In addition to analyzing serum Hsp70, we examined two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of hsp70 genes for their potential role in exceptional longevity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population

The criteria for eligibility, methods of recruitment, and study outcomes of the New England Centenarian Study (NECS) have been published elsewhere (Perls et al., 1999, Terry et al., 2003). Briefly, the NECS is an United States nationwide study of centenarians, their offspring, and controls. The controls include (a) spouses of the centenarian offspring and (b) offspring of individuals whose parents were born in the same years as the centenarians but who died at the average life expectancy for their birth cohort (hereafter referred to as septuagenarian offspring controls). The Longevity Genes Project (LGP) is a study of centenarians of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and unrelated centenarian offspring spousal controls (Atzmon et al., 2004). Both the NECS and LGP defined “centenarians” as individuals aged 95 and older and confirmed their ages with at least one form of government issued identification such as birth certificate or passport. Phenotypic data for both studies were collected by detailed interviews that included questions about demographics, medical history medications, alcohol and tobacco use, and exercise. For the NECS participants, determinations of histories or the presence of the following age-related diseases were made using a validated questionnaire (>90% correlation between the instrument and medical records for all conditions except for cataracts, which had an 88% correlation): coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, arrhythmia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cancer, stroke, dementia, osteoporosis, cataracts, glaucoma, macular degeneration, depression, Parkinson’s disease, thyroid condition, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). For LGP participants, determinations of a history or the presence of myocardial infarction were made using validated questionnaires (Rose 1962). Determination of hypertension was based on a physical examination done in the participant’s home.

2.2. Measurement of serum heat shock protein (HSP) levels

Blood samples were collected from 87 LGP centenarian subjects (sera were not available from NECS centenarian subjects), 93 NECS centenarian offspring, and 126 spousal controls (NECS controls: 43, LGP: 83). Blood samples were not obtained in the acute phase of an illness. Once collected, the blood samples were divided into aliquots and stored at -80° C. The sera were then analyzed using the classical sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method previously described by Rea and colleagues (Rea et al., 2001; Pockley et al., 2000) with minor modifications. Briefly, aliquoted serum was thawed and the total protein content was measured by Bradford analysis using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The serum was then treated with 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min at 4°C with gentle rocking. Triton X-100 is a mild detergent that dissolves the lipid containing exosomes and releases trapped Hsp70 (Bausero et al., 2005; Clayton et al., 2005; Gastpar et al., 2005; Lancaster et al., 2005). Following Trition X-100 treatment, samples were placed onto 96-well microtitre plates (Nunc Immunoplate Maxisorp; Life Technologies) that had been coated with murine monoclonal anti-human Hsp70 (clone C92F3A-5; StressGen) in carbonate buffer, pH 9.5 (2 μg/mL) overnight at 4°C, and then washed with PBS containing 1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked by incubation with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS-T. Bound Hsp72 was detected by the addition of rabbit polyclonal anti-Hsp70 antibody (SPA-812; StressGen). Bound polyclonal antibody was detected with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated murine monoclonal antibody to rabbit immunoglobulins (Sigma Chemical Co), followed by p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma Chemical Co). The resultant absorbance was measured at 405 nm with a BioRad Benmark Plus plate reader. Standard dose-response curves were generated in parallel with Hsp70 (0 to 20,000 ng/mL; StressGen), and the concentrations of Hsp70 were determined by reference to these standard curves with ASSAYZAP data analysis software (BIOSOFT). The interassay variability of the Hsp70 immunoassays was <10%.

2.3. SNP genotyping

Whole blood samples were obtained from 347 centenarians (NECS: 266, LGP: 81), 260 NECS centenarian offspring, and 238 controls (NECS: 53 spousal controls and 106 septuagenarian offspring controls, LGP: 79 spousal controls). Of note, although sera were not available from all NECS subjects for Hsp70 assays, whole blood was available for genetic studies. DNA was isolated from each subject’s peripheral blood leukocytes using the Qiagen DNA purification system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Real time PCR based SNP genotyping assays were purchased from Applied Biosystems Assays-on-Demand™ and performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Reaction products were analyzed on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence detection system. HSP70-A1A and HSP70-A1B are encoding genes members of the hsp70 family located within the cluster of human leukocyte antigen class III genes on chromosome 6p21 in the neighborhood of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) locus. These genes share the characteristic of having only one linkage disequilibrium (LD) block. Thus, we genotyped one tagSNP per gene: rs1043618 (hcv 11917510) in HSP70-A1A and rs6457452 (hcv3052604) in HSP70-A1B.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Univariate and multivariate statistics comparing LGP centenarians, NECS centenarian offspring, NECS controls and LGP controls were computed using Stata 9.1 statistical software (StataCorp 2005). Covariates included age, gender, current smoking status, presence of hypertension, and history of myocardial infarction. Fisher’s exact test was used for cells with values less than 5. We compared Hsp70 serum levels among (a) LGP centenarians versus NECS centenarian offspring, (b) LGP centenarians versus LGP controls, and (c) NECS centenarian offspring versus NECS controls using multiple linear regression adjusting for statistically significant covariates. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was determined among controls with the X2 test. Genotypic counts and allele frequencies were compared between cases and controls using multiple logistic regression. For each SNP, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and HSP analyses

As expected, the centenarians are older, predominantly female, and generally sicker than the centenarian offspring and the controls (Table 1). The youngest “centenarian” is 95 years-old, while the oldest is a female, age 108. The oldest male is 106 years-old. The age range for the NECS centenarian offspring is 54 to 88 years, for the NECS controls is 57 to 89, and for the LGP controls is 39 to 74. Despite being of similar age (p=0.497), a higher proportion of NECS centenarian offspring are disease-free compared to the NECS controls. After examining age, gender, race, income, alcohol, cardiovascular disease, and a variety of other age-related diseases in a logistic regression model, low serum Hsp70 level was the only covariate associated with being a centenarian or a centenarian offspring.

Table 1.

Characteristics of centenarians, centenarian offspring, and spousal controls enrolled in the NECS and in the LGP, expressed as Frequency (Percentage of Available Data) or as Mean (Standard Deviation)

| LGP Centenarians n = 87 | NECS Centenarian Offspring n = 93 | NECS Controls n = 43 | LGP Controls n = 83 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ±SD or n (%) | Mean ±SD or n (%) | Mean ±SD or n (%) | Mean ±SD or n (%) | |

| Mean Age, Years (SD) | 99.9 ± 2.6*** | 72.0 ± 7.2 | 72.9 ± 7.9 | 64.4 ± 6.3*** |

| Females | 64 (73.6) | 62 (66.7)* | 19 (44.2) | 55 (68.8)** |

| Current Smoker | 1 (1.6) | 1 (2.6) | 3 (3.6) | 6 (14.3) |

| Hypertension | 40 (47.6)** | 24 (28.2)* | 18 (47.4) | 41 (51.9) |

| History of Myocardial Infarction | 9 (14.3)** | 2 (2.4) | 4 (10.5) | 4 (5.4) |

Statistical tests were carried-out to compare 1) LGP Centenarians and NECS Centenarian Offspring (significance shown in the LGP Centenarians column), 2) NECS centenarian offspring and NECS controls (significance shown in the NECS Centenarian Offspring column), and 3) LGP controls and NECS controls (significance shown in the LGP Controls column). Statistical significance is denoted in bold print and its level is shown as:

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.005.

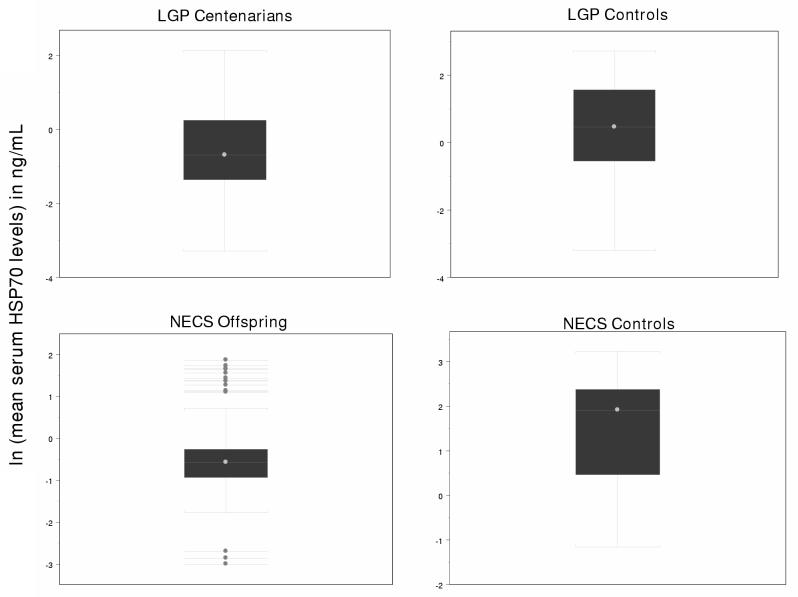

The mean and median serum Hsp70 levels (ng/mL) in each group are shown in Table 2, both unstratified and stratified by sex. Figure 1 graphically depicts the distribution of these measurements. Except for the LGP centenarians, females have slightly higher mean serum Hsp70 levels than males. Remarkably, centenarians and centenarian offspring have unadjusted mean serum Hsp70 levels close to 7-fold lower than those of the NECS controls and approximately 3-fold lower than those of the LGP controls. After the mean Hsp70 levels were adjusted for significant covariates, the paired comparison revealed that Hsp70 is significantly lower in NECS offspring than in NECS controls (sex-adjusted p <0.001) and there is a trend towards lower Hsp70 among LGP centenarians when compared to LGP controls (age-adjusted p = 0.058).

Table 2.

Serum Hsp70 levels in subject populations (ng/mL)

| Males | Females | Both | Sex-Adjusted | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NECS Centenarian Offspring (n = 93) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.95 (1.2) | 1.10 (1.5) | 1.05 (1.4) | 0.99 (0.4) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.61 (0.4) | 0.55 (0.4) | 0.56 (0.4) | <0.001 | |

| NECS Controls (n = 43) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 6.58 (5.0) | 7.36 (6.5) | 6.93 (5.7) | 6.95 (0.5) | |

| Median (IQR) | 6.87 (8.0) | 6.35 (10.4) | 6.79 (9.2) | ||

| Age-Adjusted | p-value | ||||

| LGP Centenarians (n = 87) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.69 (2.4) | 0.93 (1.1) | 1.13 (1.6) | 0.62 (0.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.51 (2.1) | 0.49 (1.0) | 0.5 (1.0) | 0.0577 | |

| LGP Controls (n = 83) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.81 (3.2) | 3.17 (3.3) | 3.07 (3.2) | 3.59 (0.8) | |

| Median (IQR) | 1.59 (3.8) | 1.48 (4.9) | 1.59 (4.2) |

Figure 1.

Log-transformed Serum Hsp70 Levels in Centenarians. Serum was collected from The Longevity Genes Project (LGP) centenarian subjects (upper left panel), LGP controls (upper right panel), New England Centenarian Study (NECS) centenarian offspring (lower left panel) and NECS spousal controls (lower right panel). Serum Hsp70 levels were measured using a modified classical sandwich ELISA with minor modifications as described in the Materials and Methods section. Bars in the figure represent the interquartile range for serum Hsp70 levels, lines represent median serum Hsp70 levels (ng/ml); dots in the boxes represent mean serum Hsp 70 levels; and dots outside the box represent outerlier values.

3.2. SNP analysis

The genes for the two subunits of hsp70 (HSP70-A1A/AHSP70-A1B) are located adjacent to each other in a 15 kb interval on human chromosome 6. Both tagSNPs (rs1043618 in HSP70-A1A and rs6457452 in HSP70-A1B) were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genotypic and the allelic association analyses revealed no significant difference when LGP centenarians were compared to the LGP controls and NECS centenarian offspring were compared to NECS controls (Table 3).

Table 3.

Genotypic analysis of tagSNPs in HSP70 for LGP and NECS participants

| LGP Centenarians | LGP Spousal Controls | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rs1043618 | ||||

| GG | 32 | 33 | Reference | |

| CG | 40 | 32 | 0.78 | 0.40-1.51 |

| CC | 9 | 14 | 1.51 | 0.58-3.90 |

| Global X2 | 1.97 p = 0.37 | |||

| Rs6457452 | ||||

| CC | 68 | 67 | Reference | |

| CT/TT | 10 | 12 | 1.22 | 0.50-2.96 |

| X2 | p = 0.67 | |||

| NECS Centenarian Offspring | NECS Controls | OR | 95% CI | |

| Rs1043618 | ||||

| GG | 111 | 66 | Reference | |

| CG | 119 | 76 | 1.07 | 0.71-1.63 |

| CC | 30 | 17 | 0.95 | 0.49-1.85 |

| Global X2 | 0.18 p = 0.91 | |||

| Rs6457452 | ||||

| CC | 225 | 131 | Reference | |

| CT/TT | 31 | 28 | 1.55 | 0.89-2.69 |

| Χ2 | p = 0.12 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Serum Hsp70 Findings

This study demonstrates that centenarians and centenarian offspring have significantly lower mean serum Hsp70 levels than unrelated controls. Centenarians and centenarian offspring have similar unadjusted levels of Hsp70. Unfortunately, since the offspring of centenarians are unrelated to the centenarians in our study, we can only speculate that the similarity in their Hsp70 levels is consistent with Hsp70 being a heritable trait.

After examining age, gender, race, income, alcohol, cardiovascular disease, and a variety of other age-related diseases in a logistic regression model, low serum Hsp70 level was the only covariate associated with being a centenarian or a centenarian offspring. While the suggestion that low serum Hsp70 level may be a predictor of longevity is attractive, we must acknowledge that this study was unable to effectively account for the effects of less prevalent age-related diseases and other environmental exposures that might influence both Hsp70 levels and longevity.

Other studies have examined Hsp70 levels in older populations. The Italian centenarian study demonstrated that there were no differences in intracellular Hsp70 among centenarians versus younger controls; however, this study did not examine serum Hsp70. In agreement with our findings, cross-sectional studies carried-out in Ireland (Rea et al., 2001) and in China (Jin et al., 2004) have demonstrated a decline in serum Hsp70 at older ages. It should be noted, however, that none of these studies, including our own, examined the changes in serum Hsp70 in the same individuals over time. Centenarians may differ from other aged subjects since they are already a highly selected surviving fraction of the general population. For example, centenarians have larger lipid particle size when compared to their offspring and younger controls (Barzilai et al., 2003). However, with Hsp70, this does not appear to be the case since LGP centenarian values were similar to those of the NECS offspring cohort.

Several reasons could explain why serum Hsp70 levels are lower at very old age. It is possible that cells in these individuals are exposed to similar levels of stress but have a diminished response of the heat shock factor-1 (Hsf-1). Hsf-1 is the transcription factor for Hsp70 and therefore regulates its synthesis in response to stress. Consistent with this, it has been shown in both rat hepatocytes (Wu et al., 1993) and in human T-lymphocyte cultures (Effros et al., 1994) that with age there is a decrease in Hsp70 synthesis. However, a recent study by Hsu and colleagues contradicts this hypothesis since Caenorhabditis elegans forced to over express the hsf-1 gene exhibited 40% greater life-span than wild type animals (Hsu et al., 2003).

Although the precise mechanism via which cells release stress proteins remains uncertain, it is clear that it is an active process that is not necessarily dependent on a loss of cellular viability (Bausero et al., 2005; Gastpar et al., 2005; Hunter-Lavin et al., 2004; Lancaster and Febbraio, 2005). Thus, another possibility is that cells from very old individuals synthesize the same amount Hsp70 intracellularly but the active release mechanism by which Hsp70 gets into the circulation is defective. This is an intriguing possibility since recent findings demonstrate that disruption of lipid rafts on cell membrane abrogates the release of Hsp70 from live cells (Bausero et al., 2005; Gastpar et al., 2005; Hunter-Lavin et al., 2004; Lancaster and Febbraio, 2005). Depletion of the lipid content of the surface membrane destroys the cells natural ability to release Hsp70 into the extracellular milieu. Consequently, stress-induced release of Hsp70 from cells is completely abrogated. Taken together, our results open the exciting possibility that Hsp70 association with longevity is related to factors downstream of gene expression.

It is plausible that those who live to very old age have always had low levels extracellularly. It may be that having low serum Hsp70 is a marker for health and that long-lived individuals have less cellular stress to respond to in the first place. In addition, having lifelong low extracellular Hsp70 levels may result in decreased exposure to inflammation. Hsp70 acts as a danger signal in conditions when it is not chaperoning peptides in its peptide binding groove (Hsp70-peptide negative proteins), and when it is carrying abnormal peptides (e.g., from viruses, bacteria or parasites). In both situations Hsp70 acts as a danger signal stimulating a potent inflammatory response that includes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, nitric oxide production and maturation of dendritic cells via the activation of the NF-κB (for review see (for review see (Asea, 2005)). It is postulated that Hsp70 peptide-negative proteins stimulate the host’s innate immune responses, whereas, Hsp70 peptide-bearing proteins stimulate adaptive immune responses (reviewed by (Asea, 2005; Calderwood et al., 2005; Pockley, 2003)). Inflammation is now well understood to contribute to age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease (Pockley, 2002; Pockley and Frostegard, 2005). This could explain why the centenarian offspring, who are similarly aged to the controls and have lower rates of cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors, have significantly lower serum Hsp70 levels (Terry et al., 2003).

Finally, it is possible that cell turnover is longer in the long-lived groups and their offspring resulting in a delay of the death pathway. Therefore less Hsp70 is released to the serum. While controls from both studies had significantly elevated serum Hsp70 levels compared to the centenarians and centenarian offspring, the NECS controls had higher levels than their LGP counterpart. Both groups had samples collected and the Hsp70 assayed using similar methods, making it unlikely that this was the result of technical differences. The LGP controls are younger and comprised of more females than the NECS controls; this may account for some of the difference. In addition, the LGP controls are of Ashkenazi Jewish descent while the NECS controls are ethnically heterogeneous. It is possible that the LGP controls may share more genetic and environmental (i.e., diet and lifestyle) traits compared to the NECS spousal controls, thus abrogating some of the serum Hsp70 elevation. Ultimately, an examination of Hsp70 levels of LGP centenarian offspring may be helpful in elucidating reasons for these differences.

The relatively low concentration of serum Hsp70 levels in our study compared to those of Rea et al who found that individuals age 90 and older have serum Hsp70 levels of about 20 ng/ml (Rea et al., 2001) does not contradict either study. An elegant study by Njemini and coworkers recently demonstrated that whereas both commercial and in-house Hsp70 ELISA are reliable and accurate at detecting Hsp70 in human serum, each gives different absolute values (Njemini et al., 2006). Serum Hsp70 concentrations of individuals aged >70 years ranged from 0-20,000 ng/ml (n=64) using their in-house ELISA versus 0-13.3 ng/ml (n=64) using the commercially available ELISA kit (StressGen). In the present study, we use a modified ELISA based on the StressGen kit in which we treat the samples with Triton X-100. It is possible that this accounts for the relatively low serum Hsp70 values in our studies. Differences in the matrix used in in-house versus commercially available Hsp70 ELISA and the possible presence of Hsp70-specific antibodies in serum which might cross-react with epitopes found on serum Hsp70, has been suggested as a possible reason for these differences (Njemini et al., 2006).

4.2. Genetic findings

The genotypic and allele frequencies of two functional tagSNPs, rs1043618 in HSP70-A1A and rs6457452 in HSP70-A1B, were examined in centenarians, centenarian offspring, and controls from the NECS and the LGP Ashkenazi Jewish population. Contrary to our hypothesis, we did not demonstrate any genetic associations that explained the differences in serum Hsp70. This could be a true finding or the consequence of the relatively small sample size of our populations. More likely, it is possible that the differences in serum Hsp70 levels that we demonstrated are a downstream effect of genetic differences elsewhere in the metabolic pathway. Future genetic studies of Hsp70 levels could focus on such genes.

4.3. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study confirms the results of our pilot study of serum Hsp70 levels in centenarian offspring compared to controls (Terry et al., 2004) and those of Rea at al (Rea et al., 2001) and Jin et al (Jin et al., 2004), showing that serum Hsp70 levels are lower in those individuals that reach an advanced age. In addition, it suggests that low serum Hsp70 levels are associated with longevity independent of other covariates such as age, gender, race, income, alcohol, cardiovascular disease, and a variety of other age-related diseases. No statistically significant associations were found with two tagSNPs within hsp70 genes. Further investigation is needed to determine why centenarians and centenarian offspring have low levels of serum Hsp70 and to better understand the role of genetic polymorphisms in this observation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susana Fiorentino for helpful discussions and Edwina Asea and Diana T. Page for expert technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the National Institute on Aging grant K08AG22785 (to D. F. T.); Paul Beeson Physician Faculty Scholar in Aging Awards (to DFT, TP, NB), the Ellison Medical Foundation Senior Scholar Award and RO1 AG-18728-01A1 (to N.B); the National Institutes of Health grant RO1CA91889, institutional support from Scott & White Memorial Hospital and Clinic, Texas A&M University System Health Science Center College of Medicine, the Central Texas Veterans Health Administration and an Endowment from the Cain Foundation (to A. A).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- Altomare K, Greco V, Bellizzi D, Berardelli M, Dato S, DeRango F, Garasto S, Rose G, Feraco E, Mari V, Passarino G, Franceschi C, De Benedictis G. The allele (A)(-110) in the promoter region of the HSP70-1 gene is unfavorable to longevity in women. Biogerontology. 2003;4:215–220. doi: 10.1023/a:1025182615693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambra R, Mocchegiani E, Giacconi R, Canali R, Rinna A, Malavolta M, Virgili F. Characterization of the hsp70 response in lymphoblasts from aged and centenarian subjects and differential effects of in vitro zinc supplementation. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:1475–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Kabingu E, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. HSP70 peptide-bearing and peptide-negative preparations function as chaperokines. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:425–431. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0425:hpbapn>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat. Med. 2000;6:435–442. doi: 10.1038/74697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Rehli M, Kabingu E, Boch JA, Bare O, Auron PE, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:15028–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A. Stress proteins and initiation of immune response: chaperokine activity of hsp72. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2005;11:34–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzmon G, Schechter C, Greiner W, Davidson D, Rennert G, Barzilai N. Clinical phenotype of families with longevity. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004;52:274–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu S, Suto R, Binder RJ, Srivastava PK. Heat shock proteins as novel mediators of cytokine secretion by macrophages. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Schechter C, Schaefer EJ, Cupples AL, Lipton R, Cheng S, Shuldiner AR. Unique lipoprotein phenotype and genotype associated with exceptional longevity. Jama. 2003;290:2030–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausero MA, Gastpar R, Multhoff G, Asea A. Alternative Mechanism by which IFN-{gamma} Enhances Tumor Recognition: Active Release of Heat Shock Protein 72. J. Immunol. 2005;175:2900–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder RJ, Harris ML, Menoret A, Srivastava PK. Saturation, competition, and specificity in interaction of heat shock proteins (hsp) gp96, hsp90, and hsp70 with CD11b+ cells. J. Immunol. 2000;165:2582–2587. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broquet AH, Thomas G, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Bachelet M. Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21601–21606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton A, Turkes A, Navabi H, Mason MD, Tabi Z. Induction of heat shock proteins in B-cell exosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:3631–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood SK, Theriault JR, Gong J. Message in a bottle: Role of the 70-kDa heat shock protein family in anti-tumor immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2005;35:2518–27. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effros RB, Zhu X, Walford RL. Stress response of senescent T lymphocytes: reduced hsp70 is independent of the proliferative block. J. Gerontol. 1994;49:B65–70. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastpar R, Gehrmann M, Bausero MA, Asea A, Gross C, Schroeder JA, Multhoff G. Heat shock protein 70 surface-positive tumor exosomes stimulate migratory and cytolytic activity of natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5238–47. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgopoulos C, Welch WJ. Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1993;9:601–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S, May MJ, Kopp EB. NF-kappa B and Rel proteins: evolutionarily conserved mediators of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:225–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu AL, Murphy CT, Kenyon C. Regulation of aging and age-related disease by DAF-16 and heat-shock factor. Science. 2003;300:1142–1145. doi: 10.1126/science.1083701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter-Lavin C, Davies EL, Bacelar MM, Marshall MJ, Andrew SM, Williams JH. Hsp70 release from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;324:511–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Wang R, Xiao C, Cheng L, Wang F, Yang L, Feng T, Chen M, Chen S, Fu X, Deng J, Wang R, Tang F, Wei Q, Tanguay RM, Wu T. Serum and lymphocyte levels of heat shock protein 70 in aging: a study in the normal Chinese population. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:69–75. doi: 10.1379/477.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen PJ, Sistonen L, Evan G, Morimoto R, Alitalo K. Nuclear colocalization of cellular and viral myc proteins with HSP70 in myc-overexpressing cells. J. Virol. 1991;65:842–851. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.2.842-851.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppner MC, Gastpar R, Gelwer S, Nossner E, Ochmann O, Scharner A, Issels RD. The role of heat shock protein (hsp70) in dendritic cell maturation: Hsp70 induces the maturation of immature dentritic cells but reduces DC differentiation from monocyte precursors. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1602–1609. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1602::AID-IMMU1602>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster GI, Febbraio MA. Exosome-dependent trafficking of HSP70: a novel secretory pathway for cellular stress proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23349–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S, Craig EA. The heat-shock proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini M, Lapalombella R, Canaider S, Farina A, Monti D, De Vescovi V, Morellini M, Bellizzi D, Dato S, De Benedictis G, Passarino G, Moresi R, Tesei S, Franceschi C. Heat shock response by EBV-immortalized B-lymphocytes from centenarians and control subjects: a model to study the relevance of stress response in longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 2004;39:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njemini R, Demanet C, Mets T. Comparison of two ELISAs for the determination of Hsp70 in serum. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006;306:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noessner E, Gastpar R, Milani V, Brandl A, Hutzler PJ, Kuppner MC, Roos M, Kremmer E, Asea A, Calderwood SK, Issels RD. Tumor-derived heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes are cross-presented by human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2002;169:5424–5432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjwani NN, Popova L, Srivastava PK. Heat shock proteins gp96 and hsp70 activate the release of nitric oxide by APCs. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2997–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perls TT, Bochen K, Freeman M, Alpert L, Silver MH. Validity of reported age and centenarian prevalence in New England. Age Ageing. 1999;28(2):193–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinhasi-Kimhi O, Michalovitz D, Ben-Zeev A, Oren M. Specific interaction between the p53 cellular tumour antigen and major heat shock proteins. Nature. 1986;320:182–184. doi: 10.1038/320182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Wu R, Lemne C, Kiessling R, de Faire U, Frostegard J. Circulating heat shock protein 60 is associated with early cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2000;36(2):303–7. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;105:1012–7. doi: 10.1161/hc0802.103729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG. Heat shock proteins as regulators of the immune response. Lancet. 2003;362:469–76. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Frostegard J. Heat shock proteins in cardiovascular disease and the prognostic value of heat shock protein related measurements. Heart. 2005;91:1124–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.059220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea IM, McNerlan S, Pockley AG. Serum heat shock protein and anti-heat shock protein antibody levels in aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2001;36:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:645–658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp LP. Stata/SE 9.1 for Windows. College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Terry DF, McCormick M, Andersen S, Pennington J, Schoenhofen E, Palaima E, Bausero M, Gor D, Perls T, Asea A. Cardiovascular disease delay in centenarian offspring: role of heat shock proteins. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004;1019:502–505. doi: 10.1196/annals.l297.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry DF, Wilcox M, McCormick MA, Lawler E, Perls TT. Cardiovascular advantages among the offspring of centenarians. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2003;58:M425–431. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.5.m425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J, Edelson JD, Post M, Mullen JB, Slutsky AS. Induction of heat stress proteins is associated with decreased mortality in an animal model of acute lung injury. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1993;147:177–181. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Gu MJ, Heydari AR, Richardson A. The effect of age on the synthesis of two heat shock proteins in the hsp70 family. J. Gerontol. 1993;48:B50–6. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.2.b50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]