Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To help referring physicians extract clinically useful information from transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) reports, highlighting current practice and innovations that are reflected with increasing frequency in reports issued by echocardiac laboratories.

QUALITY OF EVIDENCE

Echocardiography is an established science. The field has a large body of literature, including peer-reviewed articles and textbooks describing the physics, techniques, and clinical applications of TTE.

MAIN MESSAGE

Transthoracic echocardiography is a basic tool for diagnosis and follow-up of heart disease. Items of interest in TTE reports can be categorized. In clinical practice, TTE results are best interpreted with a view to underlying cardiac physiology and patients’ clinical status. Knowing the inherent limitations of TTE will help referring physicians to interpret results and to avoid misdiagnoses based on false assumptions about the procedure.

CONCLUSION

A structured approach to reading TTE reports can assist physicians in extracting clinically useful information from them, while avoiding common pitfalls.

Abstract

OBJECTIF

Aider le médecin qui reçoit le résultat d’une échocardiographie transthoracique (ÉTT) à en extraire l’information applicable en clinique, tout en soulignant les pratiques actuelles et les innovations refléteés par l’augmentation du nombre de rapports issus des centres échocardiographiques.

QUALITÉ DES PREUVES

L’échocardiographie est une technique scientifiquement reconnue. Ce domaine a fait l’objet de multiples publications, incluant des articles révisés par des pairs et des volumes décrivant les bases physiques, les techniques et les applications cliniques de l’ÉTT.

PRINCIPAL MESSAGE

L’échocardiographie transthoracique est un outil de base pour le diagnostic et le suivi des maladies cardiaques. Les points d’intérêt dans un résultat d’ÉTT peuvent être classés par catégories. En pratique clinique, on pourra mieux interpréter ces résultats si on tient compte de la physiologie cardiaque sous-jacente et de la condition clinique du patient. Le médecin qui connaît les limitations inhérentes à l’ÉTT pourra mieux en interpréter les résultats et éviter les diagnostics erronés résultant d’une méconnaissance de cette technique.

CONCLUSION

En adoptant une approche structurée pour lire un résultat d’ÉTT, le médecin saura mieux en extraire l’information cliniquement utile, tout en évitant les embûches habituelles.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS.

Echocardiographic reports are sometimes difficult to understand and to apply clinically.

This article outlines a structured approach to reading a transthoracic echocardiography report and addresses many issues often encountered by referring physicians who receive these documents.

Referring physicians should always indicate the reason the test was ordered. The limitations of transthoracic echocardiography are implicit, but technicians might state them explicitly if the referring physician explains why the test was ordered.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR.

Il est parfois difficile de comprendre les rapports d’échographie et d’en tirer des applications cliniques.

Cet article propose une façon structurée de lire un résultat d’échocardiographie transthoracique, en plus de répondre à plusieurs des questions que se posent les médecins qui reçoivent ces documents.

Le médecin qui demande une échocardiographie transthoracique devrait toujours en indiquer la raison, car le technicien pourrait alors préciser les limites de cet examen, même si celles-ci sont implicites.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), sometimes called “surface echocardiography,” is a basic tool for investigation and follow-up of heart disease. Consultants who interpret TTE endeavour to provide accurate, useful reports to colleagues who order these tests.

Referring physicians sometimes find reported results difficult to apply clinically. Terminology can be arcane. The format of reports differs from one laboratory to another. Content can vary: because echocardiography is evolving, some institutions use methods not available at all centres.

This overview will help referring physicians structure their approach to extracting clinically useful information from TTE reports. It highlights current practice and recent developments that are reflected with increasing frequency in echocardiography reports. The relevance of each item of interest is considered, and current innovations in each area are noted.

Quality of evidence

The “2-dimensional echoscope” was developed by Wild and Reid in 1952. In the past half century, echocardiography has become an established science with a vast literature. Current research appears in peer-reviewed journals. Textbooks discuss the physics, standard techniques, and clinical application of TTE.1,2

Content of TTE reports

Date of procedure.

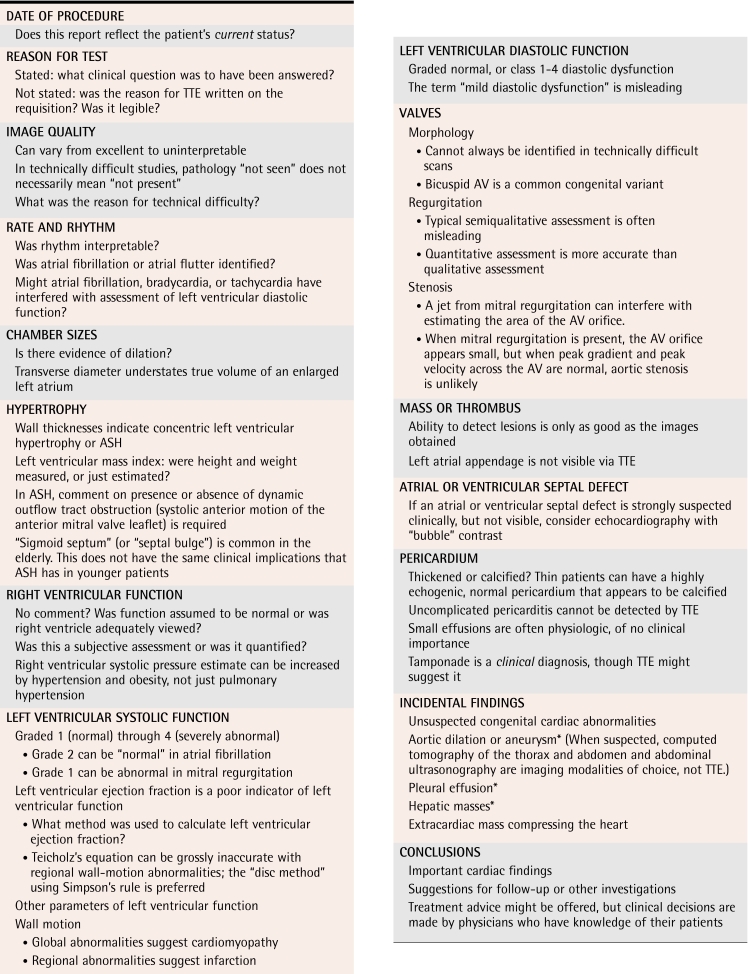

Before studying a TTE report, check its date (Table 1). Even recent studies can convey outdated impressions. Change is expected when a patient’s clinical status changes as a result of worsening disease or in response to treatment.

Table 1.

Checklist and practice points for TTE report

ASH—asymmetric septal hypertrophy, AV—aortic valve, TTE—transthoracic echocardiography.

*Could be present, even if not visible via TTE

Reason for the test.

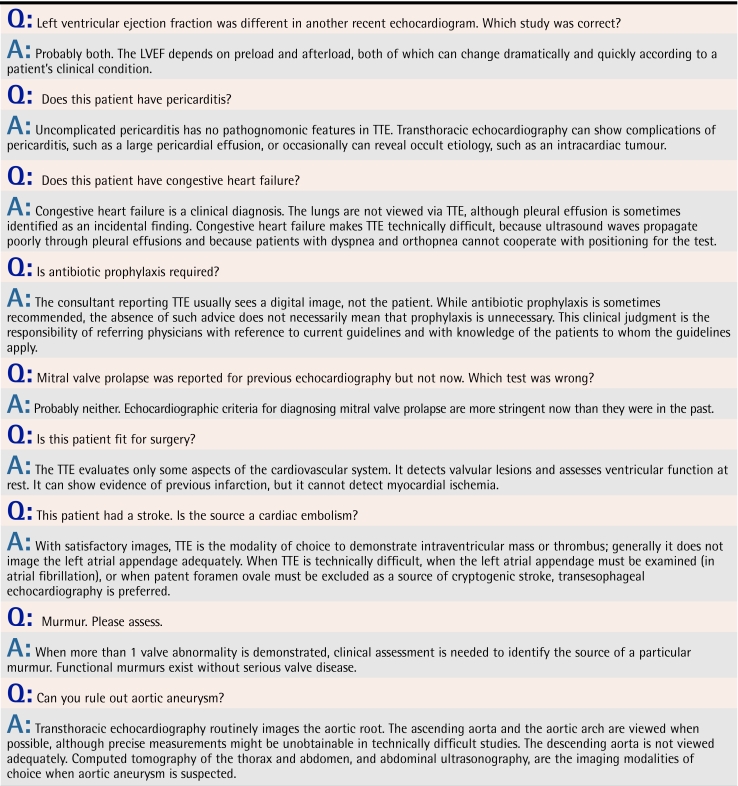

Explaining why echocardiography was ordered directs the laboratory to specific techniques that can best answer a referring physician’s question (Table 2). Sometimes the referring physician must provide data before a conclusion can be reached. Knowing the type and diameter of a prosthetic valve is prerequisite to quantifying its function. If trends in improvement or deterioration are of interest, consultants need results of previous studies.

Table 2.

Common queries and concerns in transthoracic echocardiography

TTE—transthoracic echocardiography.

Image quality.

With excellent, good, or satisfactory images, measurements in TTE are presumed accurate. Images characterized as technically difficult, fair, or poor can lead to erroneous conclusions. An error of only 1 mm in measuring wall thickness for the left ventricle (LV) translates into a 15-g difference in the estimate of LV mass.3 A report stating honestly that accurate data could not be obtained is preferable to a seemingly more “complete” analysis based on inaccurate measurements.

Qualitative conclusions also depend on image quality. A statement that “no intracardiac mass or thrombus was seen” implies no more than it states. It cannot be inferred with certainty from technically difficult TTE reports that no such lesion exists.

When image quality is unsatisfactory, the reason should be indicated. Referring physicians can decide whether invasive and more costly transesophageal echocardiography would be justified to obtain better images.

Rate and rhythm.

Correct identification of common dysrhythmias has important implications for TTE. Mild (grade II) LV systolic dysfunction with global hypokinesis is often consistent with a normal myocardium in atrial fibrillation, when the observation has no other meaning unless specific segmental wall motion defects are also identified. In atrial fibrillation, marked bradycardia or tachycardia (data commonly used to assess diastolic function of the LV) are often abnormal—not necessarily because of LV diastolic dysfunction (DD).

During TTE a rhythm strip is obtained. Sometimes cardiac rhythm is uninterpretable from a low-voltage rhythm strip, and a consultant might recommend a full electrocardiogram.

Chamber sizes.

A table often lists the measured chamber sizes (diameters) and compares them with normal values. Increased values indicate chamber dilation.

Hypertrophy.

The thicknesses of the interventricular septum and posterior LV wall are used to determine the presence of concentric LV hypertrophy or asymmetric septal hypertrophy. This practice can be misleading. Elderly patients often have a sigmoid-shaped septum that looks abnormally thick in most views.4 When asymmetric septal hypertrophy is identified, evaluation for dynamic LV outflow tract obstruction is required; specific comment regarding presence or absence of systolic anterior motion of the anterior mitral valve leaflet is expected.

Because the mass of a normal heart correlates with the size of the patient, the LV mass index in g/m2 is useful, because it relates LV mass to body surface area. Did laboratory staff measure the patient’s height and weight, or did they merely ask the patient to estimate them? Inaccurate self-reporting leads to inaccurate calculations.

Left ventricular systolic function.

Left ventricular systolic performance has long been known to indicate severity of heart disease and to predict cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. A TTE report usually classifies LV ejection fraction (LVEF) from normal (grade 1) through severely decreased (grade 4). Most laboratories quantify LVEF. For normal hearts, the Teicholz equation is reasonably accurate.5 When infarction has caused regional wall motion abnormalities, the “disc method” using Simpson’s rule is preferred.2 Reports should indicate which method was employed.

How LVEF should be interpreted depends on a patient’s clinical status and cardiac condition. While LVEF in the range of 40% to 55% is abnormal, it often has little clinical significance.6 In moderate or severe mitral regurgitation, however, even a nominally “normal” LVEF of 60% can indicate inadequate LV performance.

Left ventricular ejection fraction is a misleading indicator of LV function. It neither reflects myocardial contractility nor measures cardiac performance. Most importantly, LVEF depends on preload and afterload, both of which can change dramatically within hours.

Stroke volume, cardiac output, cardiac index, and the LV index of myocardial performance, also known as the “Tei Index,” are increasingly reported as more reliable quantifiers of LV systolic function.7 Higher values on the index of myocardial performance are associated with more severe LV disease and poorer prognosis.8

When LV systolic function is impaired, the report will indicate whether the chamber was globally hypokinetic, typical of cardiomyopathy, or whether regional wall-motion abnormalities were seen, the result of myocardial infarction. To localize and classify LV regional wall motion, the American Society of Echocardiography divides the LV into 16 segments.9 The LV wall motion score index might be reported. Higher scores indicate more dysfunction.

In many US laboratories, intravenous “bubble” contrast is used routinely to outline the LV chamber when the endocardium is poorly outlined. In Canada, financial constraints often preclude this approach.

Left ventricular diastolic function.

Diastolic dysfunction is an important factor in clinical heart failure.10 Left ventricular DD usually precedes development of LV systolic dysfunction. Where LV systolic dysfunction exists, diastolic function is inevitably abnormal. The presence and severity of DD are strong predictors of future nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the elderly.11 Independent of systolic function, DD of any degree is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality.12

Modern echocardiography either reports diastolic function as normal or grades DD by class (1 through 4).13 Class 1 DD (impaired myocardial relaxation) was formerly called “mild DD,” an expression that is obsolete and misleading. In one series, class 1 DD was associated with an 8-fold increase in all-cause mortality within 5 years.12 Mortality increases with the severity of DD.

Increased left atrial (LA) volume is a morphologic expression of DD, reflecting LV end diastolic pressure.14 It predicts development of atrial fibrillation.15 Size of the left atrium is usually represented by the transverse diameter of the chamber, although this measurement often underestimates the volume of an enlarged left atrium.

Right ventricle.

When there is no comment on function of the right ventricle, it is presumed normal by visual assessment. A few laboratories report the right-sided index of myocardial performance. This ratio is analogous to the Tei Index for LV performance.

Valvular regurgitation.

Most reports of valvular insufficiency are based on visual assessment. This common method of classifying regurgitation as trivial (or trace), mild, moderate, or severe is subjective, imprecise, and frequently misleading. Visualization by colour Doppler depends on the velocity of the jet, not the volume of blood. A small, high-velocity jet through a small orifice could thus appear to be more severe than a much larger, but slower, blood volume regurgitating through a larger orifice.16

An increasing number of laboratories quantify valvular regurgitation using the effective regurgitant orifice and the regurgitant volume of blood.17 Some reports refer to this as the “PISA” method (proximal isovelocity surface area).1,18

Valvular stenosis.

Mitral and aortic stenoses are graded as mild, moderate, or severe, based on the maximum velocity, peak gradient across the valve, and estimated cross-sectional area of the orifice. These data are usually reported. Pulmonary stenosis can be indicated by an increased pressure gradient across the valve.

Intracardiac mass or thrombus.

Clots and masses in the LV are seen best by TTE.1 The left atrial appendage is poorly visualized. Transesophageal echocardiography has better sensitivity than TTE for detecting an intra-atrial embolic source in stroke.19,20

Suspect echogenic features that could represent anatomic structures, unusual artifacts, primary or secondary cardiac tumours, thrombi, or vegetations will also be reported. Technically difficult TTE images often cannot differentiate between lesions and artifacts. Reporting physicians will point out any concerns, possibly recommending transesophageal echocardiography for clarification.

Septal defects.

The location and size of atrial and ventricular septal defects will be reported. Unless the sonographer is specifically looking for a suspected atrial septal defect, images might not be obtained from the subcostal window, the best view for detecting it.21 Contrast echocardiography can be helpful when a septal defect is suspected on clinical grounds but is not visible via TTE.

Right ventricular systolic pressure.

When failure on the right side of the heart is suspected, it is helpful to estimate the right ventricular systolic pressure or pulmonary systolic pressure. Measurements are often elevated by obesity and hypertension, not just by pulmonary hypertension.

Pericardium.

The location of pericardial effusion and its size (trace, small, medium, or large) will be reported. Small pericardial effusions are often physiologic. If an effusion is reported, referring physicians want to know whether there is evidence of tamponade, although this is ultimately a clinical diagnosis, not an echocardiographic one. Patients with uncomplicated viral pericarditis have normal echocardiogram results.1

Aorta.

The diameter of the aortic root is measured routinely. Sometimes it is possible to identify dilation of the ascending aorta, the arch, or the descending aorta. Aortic dissection is an emergency requiring immediate contact between reporting and referring physicians.

Incidental findings.

Unsuspected congenital cardiac abnormalities are discovered occasionally. Incidental findings might require investigation using other imaging modalities. Pleural effusions are often seen on the left. Intrahepatic lesions are sometimes identified and extrinsic masses compressing the heart are sometimes revealed.

Summary of findings.

The limitations of TTE are implicit, but they might be stated in the conclusions if the questions asked by referring physicians are known. For example, if a laboratory is asked to rule out cardiac embolism in a patient with atrial fibrillation and a recent stroke, the report might remind the referring physician that the left atrial appendage is not visible on TTE and that transesophageal echocardiography is recommended. When myocardial ischemia is suspected in a patient scheduled for surgery, a technician might suggest a nuclear medicine study or stress echocardiography.

Follow-up echocardiography could be suggested. Advice concerning treatment exceeds the mandate of a laboratory report, but many referring physicians appreciate recommendations for prophylactic antibiotics, when indicated.

When TTE report conclusions fail to address the reason the procedure was ordered, chances are high that the reason was never stated on the requisition. Physician-to-physician discussion can answer many queries and concerns often raised about this procedure (Table 2).

Conclusion

One imaging test cannot substitute for history taking and physical examination. In conjunction with clinical knowledge about the patient and a basic understanding of cardiac physiology, however, TTE is essential for cardiovascular evaluation and follow up. This brief review has outlined a structured approach to reading TTE reports and has addressed many issues encountered by referring physicians who receive these documents (Table 1). Echocardiography is, however, evolving rapidly. Future development of innovative techniques and consequent changes and improvements in the reports that referring physicians receive from TTE procedures are sure to come.

Biographies

Dr Neil McAlister, a specialist in internal medicine and a registered diagnostic cardiac sonographer, is Director of Echocardiography at Medical Consultants Group in Pickering, Ont.

Dr Nazlin McAlister practises family medicine in Ajax, Ont.

Dr Buttoo is a specialist in internal medicine with Medical Consultants Group.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None of the authors has any financial interest in the manufacture or sale of echocardiographic equipment. Dr Neil McAlister works in an independent facility where echocardiography is carried out upon referral from primary care physicians.

References

- 1.Otto CM. The practice of clinical echocardiography. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weyman AE. Principles and practice of echocardiography. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lea and Febiger; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King DL. Three-dimensional echocardiography: use of additional spatial data for measuring left ventricular mass. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:293–295. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krasnow N. Subaortic septal bulge simulates hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by angulation of the septum with age, independent of focal hypertrophy: an echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:545–555. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kronik G, Slany J, Mosslacher H. Comparative value of eight M-mode echocardiographic formulas for determining left ventricular stroke volume. Circulation. 1979;60:1308–1316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards WD, Tajik AJ, Seward JB. Standardized nomenclature and anatomic basis for regional tomographic analysis of the heart. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:479–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tei C, Ling LH, Hodge DO, Bailey KR, Oh JK, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. New index of combined systolic and diastolic myocardial performance: a simple and reproducible measure of cardiac function—a study in normals and dilated cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol. 1995;26(6):357–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harjai KJ, Scott L, Vivekananthan K, Nunez E, Edupuganti R. The Tei Index: a new prognostic index for patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:864–868. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiller NB, Shah PM, Crawford M, DeMaria A, Devereaux R, Feigenbaum H, et al. Recommendations for quantitation of the left ventricle by two-dimensional echocardiography. American Society of Echocardiography Committee on Standards, Subcommittee on Quantitation of Two-dimensional Echocardiograms. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1989;2:358–367. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(89)80014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, clinical features and prognosis of diastolic heart failure: an epidemiologic perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1565–1574. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsang TSM, Gersh BJ, Appleton CP, Tajik AJ, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction as a predictor of the first diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in 840 elderly men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1636–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community. JAMA. 2003;289(2):194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rakowski H, Appelton CP, Chan KL, Dumesnil JG, Honos G, Jue J, et al. Recommendations for the measurement and reporting of diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1996;9:736–760. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(96)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsang TSM, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiological expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1284–1289. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Leibson CL, Montgomery SC, Takemoto Y, et al. Left atrial volume: important risk marker of incident atrial fibrillation in 1655 older men and women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:467–475. doi: 10.4065/76.5.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCully RB, Enriquez-Sarano M, Tajik AJ, Seward JB. Overestimation of severity of ischemic/functional mitral regurgitation by color Doppler jet arm. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:790–793. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. Effective regurgitant orifice area: a noninvasive Doppler development of an old hemodynamic concept. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:443–451. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamachika S, Reid CL, Savani D, Meckel C, Paynter J, Knoll M, et al. Usefulness of color Doppler proximal isovelocity surface area in quantitating valvular regurgitation. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee RJ, Bartzokis T, Yeoh TK, Grogin HR, Choi D, Schnitther I. Enhanced detection of intracardiac sources of cerebral emboli by transthoracic echocardiography. Stroke. 1991;22:734–739. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearson AC, Labovitz AJ, Tatineni S, Comez CR. Superiority of transesophageal echocardiography in detecting cardiac source of embolism in patients with cerebral ischemia of uncertain etiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:66–72. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90705-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schub C, Dimopoulos IN, Seward JB, Callahan JA, Tancredi RG, Schattenberg TT, et al. Sensitivity of two-dimensional echocardiography in the direct visualization of atrial septal defect utilizing the subcostal approach: experience with 154 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1983;2:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(83)80385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]