Abstract

Context

National autopsy rates have declined for several decades, and the reasons for such decline remain contentious.

Objective

To elicit the opinions of one group of crucial decision makers as to the reasons for this decline and possible modes of reversal.

Design

A 2-part survey, composed of multiple choice questions and questions requesting specific data on autopsy rates and costs.

Setting

Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Participants

Hospital administrators within the 8 states.

Main Outcome Measures

Six-point survey scale relating to reasons for autopsy decline and possible remedial measures, as well as estimates of autopsy rates and costs.

Results

The response rate was 43% and the median autopsy rate was 2.4% (mean 6.1%). The median cost of autopsy was estimated at $852 (mean $1275). Larger hospitals were associated with higher autopsy rates than smaller hospitals (9.6% vs 4.0%), and teaching hospitals had a significantly higher autopsy rate than nonteaching institutions (11.4% vs 3.8%). Autopsy rates also varied by type of hospital control, with federal government hospitals having the highest autopsy rate at 15.1%. Sixty-six percent of all respondents agreed that current autopsy rates were adequate. Of the respondents, the highest percent (86%) agreed that improved diagnostics contributed to the decline in autopsies, and the highest percent (78%) agreed that direct payment to pathologists for autopsies under the physician fee schedule might lead to an increase in autopsies.

Conclusions

Our data support the conclusion that the decline in autopsy performance is multifactorial, although the variable that dominates in this analysis is the contentious perception that improved diagnostic technology renders the autopsy redundant. The rate of autopsy is conditional, at least in part, on individual hospital characteristics such as large hospital size, teaching status, and federal ownership. Three underlying factors may explain these associations: resources, mission, and case mix. An important factor in declining autopsy rates appears to be the changing economic landscape, with its increased focus on cost control within both the public and private healthcare sectors.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Introduction

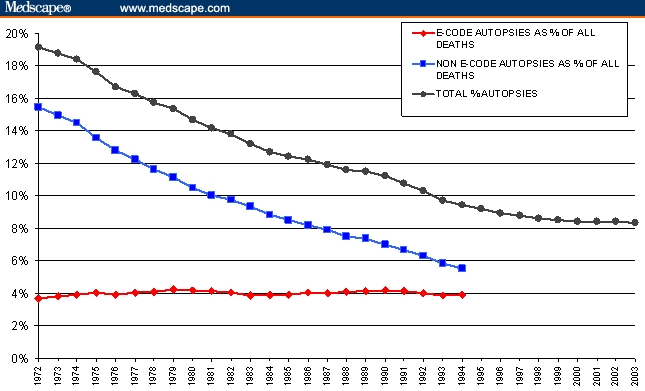

Once considered the “gold standard” in medical diagnosis, the autopsy has declined in use from 19.1% of all deaths in 1972, when the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) first began its systematic tracking of this procedure, to 9.4% in 1994, when the NCHS ceased collecting and collating national autopsy data.[1] A recent survey of all state autopsy rates by one of the authors [PNN] found a continuing decline in the national rate for the subsequent 9 years, with a national average autopsy rate of 8.3% in 2003 (Figure 1). There is evidence to suggest that autopsy rates were markedly higher than 19.1% prior to 1972, but deficiencies in data availability and quality preclude any further systematic analysis.[2–5] The rate of autopsies on unnatural deaths (including accidents, homicides, suicides, and other unusual deaths, commonly referred to as “e-code” deaths) remained relatively constant over the period from 1972 to 1994 and, consequently, have represented a higher proportion of all autopsies over time. Time series data provided by three states (Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington) suggest that the increasing dominance of e-code autopsies continues to this date. Virtually all of these are medical examiner or coroner cases by legal mandate.

Figure 1.

US autopsy rates, 1972–2003.

Source: NCHS Vital Statistics

Despite the steady decline in overall autopsy rates, this procedure offers benefits in at least 3 critical areas. First, it is a quality-control and verification mechanism with an ultimately salutary impact on clinical practice. Second, from an epidemiologic perspective, it provides accurate information on cause of death, thus facilitating the processes of hypothesis generation and testing concerning the temporal and spatial prevalence of disease.[6–8] And, third, it is a valuable instrument for achieving cost-effective healthcare and the efficient allocation of resources within the public sector by signaling the location of the most productive investments in disease treatment and control. The autopsy has also served traditionally as an important adjunct to the teaching of anatomy in particular and medicine in general, but it has continued to lose favor in this area as well.

The autopsy rate is ultimately influenced, both directly and indirectly, by a range of groups, including physicians, pathologists, coroners and medical examiners, the deceased (through advanced directives) and their relatives, as well as nursing home operators and funeral home directors.[9] While research has been conducted on the attitudes of several of these groups,[10–16] little is known about the attitudes of hospital administrators – individuals whose role in hospital matters has increased in concert with the increasing importance of the cost of healthcare delivery. In light of this fact, we surveyed hospital administrators in 8 states where declining autopsy rates have mirrored the national trend (Table 1). Our survey addressed 2 central issues: (1) the contributory causes for the declining rate of autopsy; and (2) which policies and actions might facilitate its revival, if such a course of action were deemed desirable. An additional thrust of this research effort was to examine whether the nature of hospital control (government vs private sector, profit vs nonprofit) might influence attitudes towards autopsy policy and practice.

Table 1.

Autopsy Rates for United States, 8 States, and Sample Data

| 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Deaths | ||||||||

| National | 2,151,890 | 2,173,060 | 2,179,187 | 2,271,947 | 2,279,059 | 2,313,479 | 2,316,940 | |

| 8-state sample | 269,909 | 273,562 | 268,908 | 281,314 | 280,523 | 284,557 | 281,671 | |

| No. of Autopsies | ||||||||

| National | 240,646 | 234,775 | 225,104 | 221,570 | 214,760 | 212,099 | 206,102 | |

| 8-state sample | 29,343 | 28,369 | 26,002 | 25,812 | 25,384 | 24,879 | 24,277 | |

| Autopsy rate | ||||||||

| National | 11.2% | 10.8% | 10.3% | 9.8% | 9.4% | 9.2% | 8.9% | |

| 8-state sample | 10.9% | 10.4% | 9.7% | 9.2% | 9.0% | 8.7% | 8.6% | |

| 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | ||

| No. of Deaths | ||||||||

| National | 2,315,923 | 2,340,135 | 2,393,396 | 2,405,763 | 2,419,850 | 2,443,640 | 2,445,281 | |

| 8-state sample | 277,816 | 282,608 | 289,532 | 285,840 | 286,314 | 289,399 | 289,874 | |

| No. of Autopsies | ||||||||

| National | 202,124 | 200,104 | 202,858 | 201,473 | 203,903 | 205,927 | 203,937 | |

| 8-state sample | 23,579 | 23,804 | 24,114 | 22,987 | 22,738 | 22,991 | 22,714 | |

| Autopsy rate | ||||||||

| National | 8.7% | 8.6% | 8.5% | 8.4% | 8.4% | 8.4% | 8.3% | |

| 8-state sample | 8.5% | 8.4% | 8.3% | 8.0% | 7.9% | 7.9% | 7.8% | |

Sources: 1990–1994[1] and 1995–2003 [additional survey data by one author (PNN) of all state departments of vital statistics]. Data include all 50 states and Washington, DC.

Methods

Participants

We surveyed all medical institutions within 8 states (Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Minnesota, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wisconsin [N = 1017]) that were identified as hospitals by the American Hospital Association's AHA Guide (1998–1999 Edition) to US hospitals. These states were chosen largely because of author affiliation with major teaching and research institutions in these areas. Names of hospitals, addresses, contact information, and institutional characteristics were available from the AHA Guide. We mailed our survey to the chief administrators of the hospitals and specifically requested that the survey opinion questions not be answered by a pathologist or director of clinical laboratory services. We focus on chief administrators because of their role in influencing institutional decision-making related to autopsies. Participation was voluntary, and we assured all participants that their responses would remain anonymous. Those not responding to the first mailing were approached up to 2 additional times in subsequent mailings. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center.

Survey Instrument

The initial survey was piloted in 207 hospitals in Maryland and Massachusetts. The final questions were then chosen after an iterative pretesting process that involved feedback from survey experts, physicians, and hospital administrators to ensure content and face validity. The final, 1 1/2 page survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete and included 3 questions about the adequacy of autopsy rates in their hospital, 10 questions about their opinions about why autopsy rates have fallen, and 7 questions about whether the implementation of specific policies would increase autopsy rates. All participants were asked to respond to the opinion questions using a 6-point scale corresponding to “very strongly agree,” “strongly agree,” “mildly agree,” “mildly disagree,” “strongly disagree,” and “very strongly disagree.” Participants were also asked to provide numerical data about autopsy counts, total inpatient deaths, autopsy-related costs, autopsy referral patterns, and whether their hospital had an on-site autopsy facility for the 1999 calendar year. Additional institutional data were obtained from the AHA Guide and included: hospital accreditation by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization's (JCAHO's) hospital program, teaching status, healthcare system affiliations, type of hospital ownership, and annual inpatient bed occupancy. Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) data were obtained from the US Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States.

Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis was the hospital. For statistical comparisons, we condensed “very strongly agree,” “strongly agree,” and “mildly agree” into a single “agree” category (coded as 1) and condensed “mildly disagree,” “strongly disagree,” and “very strongly disagree” into a single disagree category (coded as 0). We categorized hospitals according to the number of inpatient beds at the hospital: fewer than 50 beds, 50–99 beds, 100–199 beds, and more than 200 beds. Hospital type was coded as nonfederal government, federal government, nongovernment not-for-profit, and investor-owned for-profit. (Appendix One lists the subtypes of hospitals in each category). For each opinion question, we evaluated the association between hospital administrator agreement for a particular question and certain hospital variables using a chi-square test or chi-square test for trend.

For those hospitals that provided data related to hospital autopsy performance, we determined their autopsy rate as the ratio of the total number of autopsies divided by the total number of deaths. We calculated the mean autopsy rates for each hospital type and compared means using the t-test. We then constructed stepwise logistic regression models for the individual questions and adjusted for covariates, which we have hypothesized influence rates of autopsies within hospitals, including JCAHO accreditation, teaching status, location within an SMSA, type of hospital control, and hospital size.[8,17] Calculations were performed using the Stata statistical package, version 6.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas). Odds ratios were adjusted for all covariates reported above.

With a 10% false address rate and a 50% response rate, our responding sample could provide, with 95% confidence, an estimate of the views of 1017 hospital administrators with a sampling error of less than 4%.

Results

Opinions of Hospital Administrators

Of the 1017 surveys mailed, 44 were returned by the post office with no forwarding address and 20 hospitals acknowledged receipt but chose not to participate and returned the survey unanswered. We received 407 surveys from 953 eligible participants, yielding a response rate of 43%. Hospitals excluded from eligibility included those determined not to be medical facilities, those that had closed or whose letters were unclaimed, and hospitals whose mandate was detoxification and rehabilitation. Table 2 compares the distribution of hospital types, nationally, within our 8-state sample area, and for our survey respondents. There is no statistically significant difference among these distributions (chi-square P < .000) although, in contrast to the national data, both our 8-state sample and the survey response group have a larger percentage of nonfederal government-controlled hospitals and a lower percentage of private, for-profit institutions.

Table 2.

Distribution of Hospital Types – United States, 8 States, and Sample Data

| Hospital Types | No. in United States | No. in 8 States | No. Replied to Survey | % Response to Survey Within Each Hospital Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private, nonprofit | 3025 (59%) | 581 (57%) | 238 (58%) | 41% |

| Govt., nonfederal | 1136 (22%) | 302 (30%) | 128 (31%) | 42% |

| Private, for profit | 766 (15%) | 95 (9%) | 24 (6%) | 25% |

| Govt., federal | 240 (5%) | 39 (4%) | 17 (4%) | 44% |

| Totals | 5167 (100%) | 1017 (100%) | 407 (100%) | 40% |

Forty percent of hospitals provided adequate supplemental data about autopsy performance (n = 385) for analysis. The mean number of reported inpatient deaths for 1999 was 143 ± 188, and the median autopsy rate was 2.4% (mean = 6.1%). Of those hospitals that reported inpatient deaths, 48% also reported that no autopsies were performed at their facility or were referred out to a different facility for autopsy. Sixty percent of hospitals reported that they had no on-site autopsy facility. However, more than half of those hospitals that reported no on-site autopsy facility referred cases to an outside facility for autopsy (excluding forensic cases). Of the 40% of hospitals that were reported to have an on-site autopsy facility, no autopsies were performed in 5% of those institutions.

Autopsy rates tended to vary by hospital characteristic. Table 3 reports autopsy rates for the 4 major categories of hospitals, including only those hospitals that provided the number of deaths as well as autopsy numbers and rates (n = 327). Table 4 presents pair-wise t-tests for the differences of means. Larger hospitals were associated with higher autopsy rates than smaller hospitals. Hospitals with 200 beds or more were much more likely to have a teaching program than hospitals with less than 50 beds (odds ratio [OR] = 22.1, 95% confidence interval [CI] 10.0–48.9), and teaching hospitals had a significantly higher autopsy rate than nonteaching institutions. Autopsy rates also varied by type of hospital control. The only significant differences were between federal government and investor-owned for-profit and nonfederal government hospitals, with federal government hospitals having the highest autopsy rate.

Table 3.

Autopsy Rate by Hospital Characteristics

| Autopsy Rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Category | Count | Weighted mean* | Unweighted mean |

| Hospital Size | |||

| ≥ 200 beds | 83 | 9.6% | 12.8% |

| 50–199 beds | 156 | 4.9% | 6.1% |

| < 50 beds | 88 | 2.5% | 3.1% |

| Teaching status | |||

| yes | 78 | 11.4% | 14.4% |

| no | 249 | 3.8% | 4.8% |

| Ownership | |||

| federal government | 14 | 15.1% | 13.3% |

| nongovernment, nonprofit | 187 | 7.7% | 7.7% |

| investor-owned for-profit | 19 | 6.2% | 6.1% |

| nonfederal government | 107 | 5.6% | 5.0% |

weighted by bed count

Table 4.

T-Tests of Pairwise Comparisons of Means (P Values) for Autopsy Rates by Hospital Characteristics

| Teaching Status (Yes/No) | P = .000* | ||

| Hospital Size | 50–199 beds | < 50 beds | |

| ≥ 200 beds | P = .002* | P = .000* | |

| 50–199 beds | P = .017* | ||

| Ownership | nongovernment, nonprofit | investor-owned for-profit | nonfederal government |

| federal government | P = .153 | P = .028* | P = .006* |

| nongovernment, nonprofit | P = .639 | P = .098 | |

| investor-owned for-profit | P = .702 |

= significant at the 5% level

Forty-two percent of the sample (n = 399) completed the opinion portion of the questionnaire. When asked whether autopsy rates in their hospital were appropriate, 66% of all respondents agreed either mildly, strongly, or very strongly that current autopsy rates were adequate. Of the 34% who felt that current rates were not adequate, however, 97% agreed that rates should be higher, while 99% disagreed that rates should be lower.

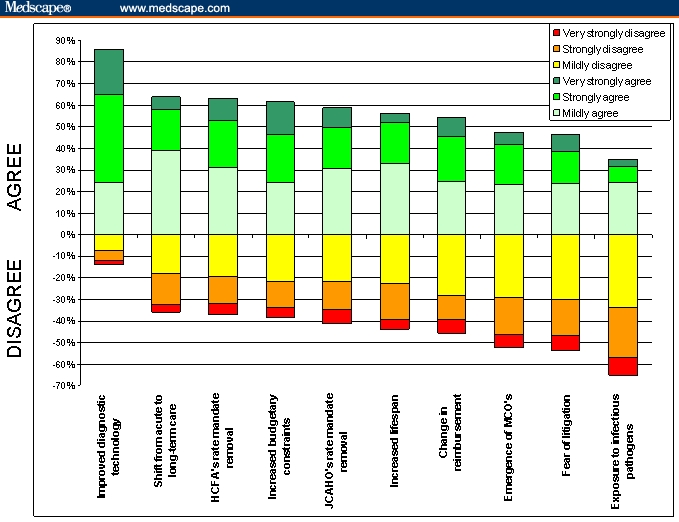

The survey responses to the question concerning perceived reasons for the decline in autopsy rates can be divided into 2 general categories: 1 reason with strong support (improved diagnostics – 86% agreement), and 9 reasons for which there was substantial disagreement and/or for which there was no strong opinion either way (Figure 2). Of this latter group of reasons for autopsy rate decline, hospital administrators' agreement about their contribution ranged from a high of 64% for the shift in care from acute care hospitals to nursing homes and hospice care, to a low of 35% for exposure to infectious pathogens.

Figure 2.

Hospital administrators' opinions about declining autopsy rates.

Hospital characteristics appeared to influence administrators' opinions about why autopsy rates have declined. Administrators were less likely to agree that the increase in the average life span has led to the decline in autopsy rates if their hospital resides in an SMSA (OR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.42–0.99), if their hospital is accredited by the JCAHO (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.32–0.82), or autopsies had been performed on patients who had died within their hospital (OR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.26–0.65).

Administrators whose hospitals were designated as teaching hospitals were less likely to agree that increased budgetary constraints have led to a decline in autopsy rates (OR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.24–0.68). Administrators were twice as likely to agree that the threat of litigation has led to the decline in hospital autopsies if their hospital resides in an SMSA (OR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.3–2.97) or if autopsies were performed on patients who had died within their facility (OR = 2.1, 95% CI 1.34–3.44).

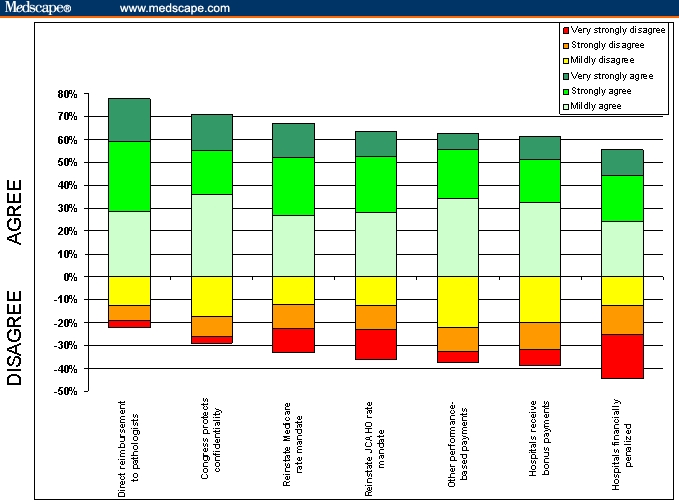

When questioned about incentives that might result in increasing hospital autopsy rates, the 2 policies that received the highest level of agreement from hospital administrators were direct payment to pathologists for autopsies under the physician fee schedule (78%) and enactment of legislation by Congress to protect the confidentiality of healthcare error reporting (71%) (Figure 3). The 5 other possible policy options ranged from a high of 67% agreement for reinstating the Medicare autopsy rate mandate to a low of 55% for financial penalties for hospitals not meeting a target autopsy rate.

Figure 3.

Hospital administrators' opinions about raising autopsy rates.

Hospital characteristics also influenced administrators' opinions about which policies were likely to raise hospital autopsy rates. Administrators whose hospitals reside within an SMSA were more likely to agree that reinstitution of a minimum autopsy rate mandate by the JCAHO would increase rates (OR = 1.5, 95% CI 0.96–2.4), and administrators of teaching hospitals were more than twice as likely to agree that bonus payments for hospitals achieving targeted autopsy rates would lead to increased rates (OR = 2.2, 95% CI 1.2–4.0).

Hospital Autopsy Patterns and Costs

Only 11% (105/953) of the hospitals responded with autopsy cost information. Three specific questions were asked with respect to autopsy cost: the total per-case cost of performing autopsies, the total per-case cost of referral autopsies, and the total variable costs (eg, personnel and materials) exclusive of overhead (fixed costs). The total per-case costs averaged $1275 and ranged from $100 to $7500 [median value = $853]. The principal problem with using these cost estimates is that they include prorated fixed costs and will clearly vary according to the number of autopsies performed at each facility. The ideal economic estimate is marginal cost; but failing the availability of this cost estimate, one can utilize 2 possible surrogate variables: the cost per referral case or the average variable cost of in-house autopsies. From our sample, these values were calculated at $1062 and $1123, respectively (in 1999 dollars). [Updating to April 2006 using the medical care component of the US Consumer Price Index yields a range of $1418-$1450 per autopsy.]

Discussion

In the past half century, concern has been raised about the declining number of autopsies performed on patients dying within hospitals. Three studies have reported historical data suggesting autopsy rates in some hospitals in the 1950s and 1960s to be in the 50% to 85% range.[2,3,10] A number of reasons for this decline have been postulated, including:[18] improvements in diagnostic technology, fear of litigation, removal of defined minimum autopsy rate standards, a lack of direct reimbursement, as well as the lack of standardization of the autopsy as a medical procedure with resultant lack of credibility as a valid outcome or performance measure. Although there is little evidence to support any of these stated reasons for the decline in autopsies, some researchers have sought to explore determinants of autopsy.[17] Most of the emphasis has been on patient-related characteristics, with only a few studies including institutional factors related to autopsy performance.

In this study, we have re-examined the complex issue of declining autopsy rates, their cause, and possible remedial measures. We have specifically focused our analysis on the hospital administrator as an important locus of decision-making in the ongoing debate over the value of autopsies. Our finding that the median inpatient autopsy rate in a sample of hospitals was 2.4% (mean 6.1%) for 1999 contrasts with the findings of an earlier survey of autopsy rates among 410 hospitals in the United States and Canada during the 1990s, which found an aggregate autopsy rate of 12.4% and a median rate of 8.3%.[19] The difference between the results of these 2 studies is most likely a reflection of the secular decline in autopsy rates in the United States.

Although we asked individual institutions to report both the direct and indirect costs of performing autopsies, most could not provide these data. Our estimate of the average variable cost of autopsies in 1999 of between $1062 and $1123 (median $853) contrasts with the findings of one other survey of autopsy costs,[20] which surveyed 188 medico-legal offices throughout the United States and found that the average fee paid to pathologists per autopsy was $518 in 1993. Detailed autopsy cost data from our own institutions suggest that personnel costs per autopsy are approximately 93.5% of total variable costs. After adjusting for inflation within the healthcare sector, our results suggest an average labor cost of $798 to $844 (1993 dollars). This is considerably higher than the estimates generated by Jason and colleagues,[20] although this difference may be due to the fact that they gathered cost data on medico-legal autopsies only. The authors speculate that the main reason why their cost estimates were considerably lower than published estimates of autopsy costs may have been due, in part, to the willingness of residents and forensic pathology fellows to perform autopsies at a loss for reasons of medical education or community service.

Our data support the general conclusion that explanations for autopsy rates are multifactorial and are conditional, at least in part, on individual hospital characteristics. Three institutional characteristics, in particular, seem to be associated with higher autopsy rates: large hospital size, teaching status, and federal ownership. It is possible to hypothesize that 3 underlying factors may explain these associations: resources, mission, and case mix. Larger hospitals and the federal government may, on balance, be expected to control greater resources and, therefore, have the ability to fund a higher autopsy rate. Teaching and federal hospitals may have missions that indirectly encourage higher autopsy rates. Most obvious among these are teaching hospitals whose educational mandate is advanced by the information yield of autopsies. In addition, among federal hospitals, higher autopsy rates may be the consequence of an explicit or implicit mandate to ultimately address the medical and public health needs of a broader national community. Among larger hospitals, the greater volume and complexity of case loads may lead to more medical questions whose resolution may be facilitated by autopsy-generated information. One additional factor that may affect the autopsy rate but is not explored here is whether families in any of these states must incur out-of-pocket expenses if they desire an autopsy for their deceased relative.

Of the 10 hypothesized reasons for the decline in autopsy rates, 7 were deemed to be important by over 50% of our sample of hospital administrators, although the most important is clearly improved diagnostic technology. Despite this perception, several recent research studies have suggested that new diagnostic technology does not obviate the need for autopsies for detection of clinical errors as well as verification of diagnostic procedures and data interpretation.[21–26] Any effort to increase the autopsy rate must confront this lack of congruence between perception and empirical evidence.

With respect to the appropriate level of autopsy rates, only 25% of our sample felt that rates should be higher. All 7 of the postulated incentives for increasing these rates received more than 50% support, but the most important (the direct reimbursement of pathologists for their services) and 3 other possible initiatives are financial in nature. This finding supports the conclusion that an important force in declining autopsy rates is the changing economic landscape, with its increased focus on cost control within both the public and private healthcare sectors. At the root of this issue is the contrast between: (1) the immediate, tangible, and usually nonreimbursed costs of the autopsy; and (2) its medium- to long-term, diffuse, and intangible social benefits, which are difficult to price. Within the discipline of economics, this falls squarely into the category of “market failure.”[9] Only a monetization of such benefits can resolve this particular facet of the problem. Until then, any conclusion about the appropriate level of the autopsy and whether the benefits of the autopsy are worth its cost is premature.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude for the insightful comments of an anonymous referee. We remain responsible for any omissions or ambiguities of interpretation.

Appendix: Classification Codes for Hospitals

Government, nonfederal

State, county, city, city-county, hospital district or authority

Nongovernment not-for-profit

Church operated, other

Investor-owned (for-profit)

Individual, partnership, corporation

Government, federal

Air Force, Army, Navy, Public Health Service excluding Indian Service, Veterans Affairs, Department of Justice, PHS Indian Service, other federal

Source: American Hospital Association. The AHA Guide 1998–1999 Edition. Chicago, Ill: American Hospital Association; 1998.

Contributor Information

Peter N. Nemetz, Strategy and Business Economics Division, Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; Email: peter.nemetz@sauder.ubc.ca.

Eric Tangalos, Department Chair-Primary Care Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Department of Primary Care Internal Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota.

Laura P. Sands, Purdue University, School of Nursing, Johnson Hall of Nursing, West Lafayette, Indiana.

William P. Fisher, Jr., Avatar International Inc., Orlando Corporate Center, Sanford, Florida.

William P. Newman, III, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Department of Pathology, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Elizabeth C. Burton, Autopsy Pathology, Baylor University Medical Center; Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Baylor Health Care System, Dallas, Texas.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Multiple Causes of Death data tapes, various years.

- 2.Nemetz PN, Ballard D, Beard M, et al. An anatomy of the autopsy, Olmsted County, 1935–85. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)64974-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lundberg G. Low-tech autopsies in the era of high-tech medicine: continued value for quality assurance and patient safety. JAMA. 1998;28:1274–1275. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.14.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundberg G, Stacey J. Severed Trust: Why American Medicine Hasn't Been Fixed – and What We Can Do About It. New York: Basic Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minnesota death tapes, Minnesota Department of Health, St. Paul, Minnesota.

- 6.Nemetz PN, Beard M, Ballard D, et al. Resurrecting the autopsy: benefits and recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)64975-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton EC, Nemetz PN. Medical error and outcome measures: where have all the autopsies gone? Medscape General Medicine. 2000;2(2) Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/408053. Accessed August 22, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, Goldman L. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:2849–2856. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nemetz PN, Ludwig J, Kurland LT. Assessing the autopsy. Am J Pathol. 1987;128:362–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nemetz PN, Tangalos EG, Kurland LT. The autopsy and epidemiology - Olmsted County, Minnesota and Malmo, Sweden. APMIS. 1990:765–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1990.tb04998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPhee SJ, Bottles K, Lo B, Saika G, Crommie D. To redeem them from death: reactions of family members to autopsy. Am J Med. 1986;80:665–671. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90822-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Start RD, McCulloch TA, Silcocks PB, Cotton WK. Attitudes of senior pathologists towards the autopsy. J Pathol. 1994;172:81–84. doi: 10.1002/path.1711720113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Start RD, Cotton DW. The meta-autopsy: changing techniques and attitudes towards the autopsy. Qual Assur Health Care. 1993;5:325–332. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/5.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Midelfart J, Aase S. The value of autopsy from a clinical point of view. A survey of 250 general practitioners and hospital clinicians in the county of Sor-Trondelag, Norway. APMIS. 1998;106:693–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Start RD, Saul CA, Cotton DWK, Mathers NKJ, Underwood JCE. Public perceptions of necropsy. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:497–500. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.6.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birdi KS, Bunce DJ, Start RD, Cotton DW. Clinicians' beliefs underlying autopsy requests. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:24–28. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.72.846.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nemetz PN, Leibson C, Naessens J, Beard M, Tangalos E, Kurland LT. Determinants of the autopsy decision: a statistical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:175–183. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/108.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastings M, Andes S. Brief Report Series 97-A. Chicago, Ill: The Institute of Medicine of Chicago; 1997. Autopsy – past and present: summary of the Institute's Autopsy Research Program and of the 1995 Annual Autopsy Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker PB, Zarbo RJ, Howanitz PJ. Quality assurance of autopsy face sheet reporting, final autopsy report turnaround time, and autopsy rates: a College of American Pathologists Q-Probe study of 10003 autopsies from 418 institutions. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1996;120:1003–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jason DR, Lantz PE, Preisser JS. A national survey of autopsy cost and workload. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:270–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutrone JA, Georgiou D, Khan SU, Pollack A, Laks MM, Brundage BH. Right ventricular mass measurement by electron beam computed tomography. Validation with autopsy data. Invest Radiol. 1995;30:64–68. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199501000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein PD. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1996;2:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar P, Taxy J, Angst DB, Mangurten HH. Autopsies in children: are they still useful? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:558–563. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsujimura T, Yamada Y, Kubo M, Fushimi H, Kameyama M. Why couldn't an accurate diagnosis be made? An analysis of 1044 consecutive autopsy cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:408–410. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.1999.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiesel E, Hanzlick R. Case of the Month. The autopsy and new technology: all that glitters is not a gold standard. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1901–1902. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.13.1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun CC, Alonsonzana G, Love JC, Li L, Straumanis JP. The value of autopsy in pediatric cardiology and cardiovascular surgery. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:491–496. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]