Abstract

Context

Many of the new antiepileptic drugs have psychiatric indications, and most are prescribed by psychiatrists for patients with mood disorders, even when a specific indication is absent. Epileptic drugs as a whole, even the newer ones, are known to affect cognition, sometimes in untoward ways. Research on the neurocognitive effects of antiepileptic drugs, however, has been done exclusively in normal volunteers and in patients with seizure disorders.

Method

A naturalistic, cross-sectional study was conducted on patients who were taking 1 of 5 different antiepileptic drugs or lithium (LIT). Cognitive status was measured by a computerized neurocognitive screening battery, CNS Vital Signs (CNSVS).

Subjects

One hundred fifty-nine patients with bipolar disorder, aged 18-70 years, were treated with carbamazepine (CBZ) (N = 16), lamotrigine (LMTG) (N = 38), oxcarbazepine (OCBZ) (N = 19), topiramate (TPM) (N = 19), and valproic acid (VPA) (N = 37); 30 bipolar patients were treated with LIT.

Results

Significant group differences were detected in tests of memory, psychomotor speed, processing speed, reaction time, cognitive flexibility, and attention. Rank-order analysis indicated superiority for LMTG (1.8) followed by OCBZ (2.1), LIT(3.3), TPM (4.3), VPA (4.5), and CBZ (5.0).

Conclusion

The relative neurocognitive effects of the various psychotropic antiepileptic drugs in patients with bipolar disorder were concordant with those described in the seminal literature in normal volunteers and patients with epilepsy. LMTG and OCBZ had the least neurotoxicity, and TPM, VPA, and CBZ had the most. LIT effects on neurocognition were intermediate. Choosing a mood-stabilizing drug with minimal neurocognitive effects may enhance patient compliance over the long term.

Introduction

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) exercise suppressant effects on neuronal excitability, and thus can cause cognitive impairment.[1,2] The neurocognitive effects of AEDs, when they occur, have diverse presentations. They may be general, for example, cognitive blunting or psychomotor slowing, or they may be specific. Memory and attention are especially vulnerable to AED neurotoxicity. Cognitive effects of AEDs, when and if they occur, tend to be dose-related. They are more likely to occur when more than 1 AED is prescribed concomitantly.[3,4]

Although AEDs are prescribed with increasing frequency to patients with psychiatric disorders, very little has been written on the subject of AED-related cognitive impairment in these patients. Many of the new drugs that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as mood stabilizers are also AEDs (eg, VPA, CBZ, and LMTG). In bipolar disorder, AEDs are useful alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate or who fail to respond to LIT or antipsychotic drugs.[3,5–17] Because the therapeutic efficacy of LIT, VPA, CBZ, and LMTG is roughly equivalent, physicians who treat patients with mood disorders may encounter difficulty in selecting one drug over another.

The comparative effects on cognition of the psychotropic AEDs would be an area of interest if they were a factor in the decision to choose one drug over another. In the treatment of bipolar disorder, for example, a drug that spares cognition would be preferred to one that doesn't. Bipolar patients are particularly sensitive to perceived drug side effects, and selecting the right drug always tends to improve compliance.

Studies of AED effects on neurocognition have been conducted almost exclusively in normal volunteers and patients with epilepsy. In these studies, CBZ and VPA were demonstrated to be superior to diphenylhydantoin (DPH),[4,18–23] although neither CBZ nor VPA is entirely free of negative cognitive effects.[21,24] These negative effects were more apparent when CBZ and VPA were compared with the newer AEDs.[25] New AEDs, such as gabapentin, levetiracetam, LMTG, tiagabine, and OCBZ, appear to be better tolerated than DPH, CBZ, and VPA, and their toxicity profiles in neuropsychological tests tend to be benign.[24,26] The only new AEDs that possess significant negative cognitive effects are TPM and zonisamide (ZON), which have diffuse cognitive effects that are similar to the older AEDs, as well as specific effects on language.[3,24] The epilepsy literature indicates that there is a spectrum of neurotoxicity among the AEDs.

We thought that it would be interesting to see whether patients with psychiatric disorders expressed a similar pattern of response to the psychotropic AEDs. To address this question, we analyzed a clinical series of 129 bipolar patients who had been successfully treated with one of the modern AEDs, and who had been evaluated with a neurocognitive test battery.

Methods and Materials

This was a cross-sectional, naturalistic study of neurocognitive performance in patients with bipolar disorder who had responded satisfactorily to one of the following mood-stabilizing drugs: CBZ (N = 6), LMTG (N = 38), LIT (N = 30), OCBZ (N = 19), TPM (N = 19), and VPA (N = 37). LIT, of course, is neither a new mood stabilizer nor an AED. Data from LIT-treated patients were included for purposes of comparison. (None of the bipolar patients in our clinic database were treated with DPH, and very few were on ZON.)

Subjects

The subjects of this investigation were patients with bipolar affective disorder. They were all outpatients at the North Carolina Neuropsychiatry Clinics in Chapel Hill and Charlotte, North Carolina. They had been treated with one of the mood-stabilizing drugs listed above, and had achieved, in the judgment of their treating doctors, an optimal clinical response. The patients who were selected for this investigation had been on a stable dose of drug for at least 4 weeks.

Cognitive Evaluation

Patients' neurocognitive performance was measured on a computerized battery of tests, CNS Vital Signs (CNSVS). CNSVS is a PC-based neurocognitive screening battery composed of 7 familiar neuropsychological tests: verbal and visual memory, finger tapping, symbol-digit coding, the Stroop test, the shifting attention test, and the continuous performance test. The test battery is self-administered in the clinic on a computer, and takes about 30 minutes.

The tests in the CNSVS battery are reliable (test-retest, r = 0.65-0.88).[27] Normative data from 500 normal subjects, aged 10-89 years, indicate typical performance differences by age and sex.[28] Concurrent validity was established in studies comparing the CNSVS battery with conventional neuropsychological tests.[29,30]

The CNSVS tests are reported as raw test scores from the individual tests (15 “primary variables,” eg, correct responses, errors, and reaction time). The 7 tests in turn generate 5 “domain scores,” empirically derived by factor analysis. These are memory (derived from and verbal and visual memory), psychomotor speed (from finger tapping and symbol-digit coding), reaction time (Stroop test), cognitive flexibility (Stroop test and shifting attention test), and complex attention (Stroop test, shifting attention test, and continuous performance test). (“Cognitive flexibility” is an executive control function.) These are reported as standard scores (z scores standardized to a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15).

The average of the z scores for 5 domains generates a summary score, which is reported as a standard score (the Neurocognition Index [NCI]). This is similar to an IQ score on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) or the Stanford-Binet, which is generated by averaging the z scores of the various subtests.

Method

The CNSVS database contains records from more than 2000 patients with neurologic and/or psychiatric disorders. The database was scanned for patients who met the following criteria: primary diagnosis, bipolar affective disorder; age, 18-70 years; no comorbid neurologic conditions or cognitive disorders (eg, dementia or brain injury); monotherapy with CBZ, LMTG, LIT, OCBZ, TPM, and VPA; stable doses maintained for at least 4 weeks; no other centrally acting drugs.

An independent chart review affirmed the diagnosis (by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision [DSM-IV-TR] criteria) and established that the treating clinician considered the patient to be a positive responder to the medication. No further medication changes were recommended or contemplated. All of the patients were tested within a 14-month period (July 2003-August 2004).

CNSVS generates 15 primary scores, 5 domain scores, and 1 composite score. Group differences were assayed by multivariate analysis, taking as covariates patient age, race, and sex. If a multiple analysis of variance (MANOVA) indicated significant group differences, pairwise t tests were done to determine the source of the difference.

Results

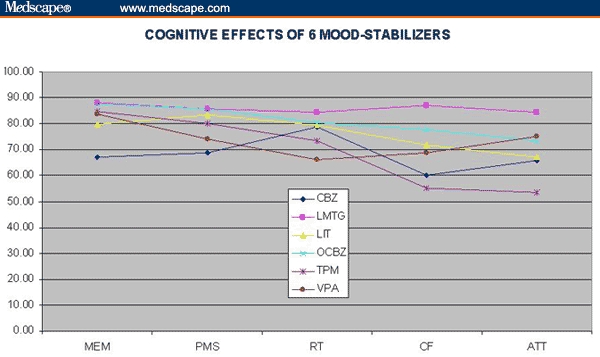

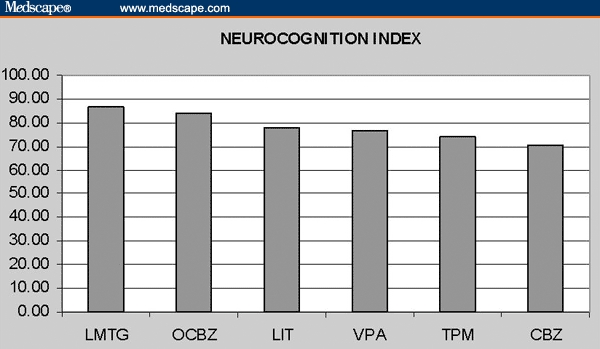

Table 1 shows data from the 159 patients, their age, medication and dose, and test scores. Immediately below the row “age,” is the NCI, the 5 domain scores, followed by the 15 raw test scores. Summary data are expressed graphically in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1.

One Hundred Fifty-Nine Patients on Mood Stabilizers and Mean Test Scores

| Test Score | CBZ | LMTG | LIT | OCBZ | TPM | VPA | Total (N =159) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 38 | 30 | 19 | 19 | 37 | MANOVA | |

| Age | 43.19 | 42.05 | 30.60 | 36.47 | 41.11 | 41.24 | F | P < |

| Neurocognition Index | 70.15 | 86.73 | 77.75 | 83.91 | 74.16 | 76.48 | 2.27 | .05 |

| Memory | 66.95 | 88.02 | 79.62 | 87.75 | 84.79 | 83.67 | 1.76 | .12 |

| Psychomotor speed | 68.78 | 85.70 | 83.29 | 85.84 | 80.05 | 74.13 | 2.41 | .04 |

| RT | 78.62 | 84.22 | 79.30 | 80.56 | 73.56 | 65.95 | 1.91 | .10 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 60.28 | 87.03 | 71.79 | 77.74 | 55.24 | 68.71 | 3.13 | .01 |

| Complex attention | 65.75 | 84.53 | 67.11 | 73.28 | 53.48 | 75.12 | 2.29 | .05 |

| Verbal memory | 44.87 | 47.85 | 46.58 | 48.47 | 48.16 | 47.99 | 0.59 | .71 |

| Visual memory | 37.69 | 44.95 | 42.59 | 44.58 | 42.63 | 41.81 | 3.21 | .01 |

| Finger tapping | 85.59 | 100.18 | 101.53 | 98.12 | 99.08 | 90.62 | 1.44 | .21 |

| Symbol-digit coding | 34.81 | 47.32 | 47.53 | 49.84 | 40.53 | 37.03 | 3.91 | .00 |

| Stroop simple RT* | 425.69 | 368.39 | 347.57 | 357.89 | 379.66 | 452.64 | 1.76 | .12 |

| Stroop complex RT* | 750.94 | 660.03 | 686.50 | 706.42 | 775.89 | 778.46 | 2.15 | .06 |

| Stroop part 3 RT* | 773.73 | 808.21 | 798.98 | 791.42 | 810.00 | 945.35 | 3.19 | .01 |

| Stroop test errors* | 7.66 | 3.11 | 3.40 | 5.84 | 3.84 | 3.08 | 2.38 | .04 |

| SAT correct | 33.52 | 46.11 | 40.10 | 45.84 | 36.25 | 35.70 | 3.59 | .00 |

| SAT errors* | 17.05 | 9.32 | 13.71 | 11.53 | 22.26 | 14.19 | 3.16 | .01 |

| SAT RT* | 1175.1 | 1114.4 | 1124.9 | 1032.5 | 1016.1 | 1212.5 | 2.22 | .06 |

| SAT efficiency* | 2.45 | 1.55 | 2.41 | 1.40 | 1.93 | 2.03 | 1.67 | .14 |

| Continuous performance test correct | 36.97 | 39.13 | 38.13 | 39.18 | 36.57 | 38.05 | 1.45 | .21 |

| CPT errors* | 8.67 | 1.68 | 3.91 | 3.58 | 18.30 | 3.89 | 3.28 | .01 |

| CPT RT* | 526.66 | 450.29 | 511.88 | 433.22 | 487.26 | 541.74 | 2.07 | .07 |

CBZ = carbamazepine; LMTG = lamotrigine; LIT = lithium; OCBZ = oxcarbazepine; TPM = topiramate; VPA = valproic acid; RT = reaction time; SAT = shifting attention test

SAT efficiency is calculated as (SAT RT/percentage correct)/1000; a lower score is better.

An asterisk indicates tests on which a lower score is better than a higher score.

Figure 1.

Cognitive effects of 6 mood stabilizers.

Figure 2.

Neurocognition Index.

Group differences were apparent for the summary cognitive score, the NCI, for 3 domains – psychomotor speed, cognitive flexibility, and complex attention – and for the following tests: visual memory, coding, Stroop reaction time and errors, shifting attention test correct and errors, and continuous performance test errors. Pairwise statistics for the NCI indicated significant differences between LMTG and CBZ (t = 3.00, P = 004), LMTG and LIT (t = 2.01, P = .043), LMTG and TPM (t = 2.41, P = .019), and LMTG and VPA (t = 2.17, P = .03) – but not among any of the other drugs.

When the scores of the LMTG patients were compared with those of patients on the other 5 mood stabilizers, significant differences were observed in the NCI (t = 2.59, P < .01), reaction time (t = 1.96, P = .05), cognitive flexibility (t = 3.06, P = .003), and complex attention (t = 2.44, P = .016).

The relative ranks of the test and domain scores for the 6 mood stabilizers are given in Table 2. LMTG ranked first in the NCI and in 4 of the 5 domain scores (Kendall's W = 0.68, chi square = 23.9, P = .0002), and first or second in 10 of the 15 test scores (Kendall's W = 0.46, chi square = 34.8, P < .0001).

Table 2.

Rank-Order Analysis

| Test Score | CBZ | LMTG | LIT | OCBZ | TPM | VPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurocognition Index | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Memory | 6 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Psychomotor speed | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| RT | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Complex attention | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 |

| Verbal memory | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Visual memory | 6 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Finger tapping | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| Symbol-digit coding | 6 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Stroop simple RT* | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Stroop complex RT* | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Stroop part 3 RT* | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 6 |

| Stroop test errors* | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Shifting attention test correct | 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Shifting attention test errors* | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Shifting attention test RT* | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Shifting attention test efficiency* | 6 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| CPT correct | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| CPT errors* | 5 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| CPT RT* | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 6 |

| Rank | 5.0 | 1.8 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 4.5 |

CBZ = carbamazepine; LMTG = lamotrigine; LIT = lithium; OCBZ = oxcarbazepine; TPM = topiramate; VPA = valproic acid; RT = reaction time; CPT = continuous performance test

An asterisk indicates tests on which a lower score is better than a higher score.

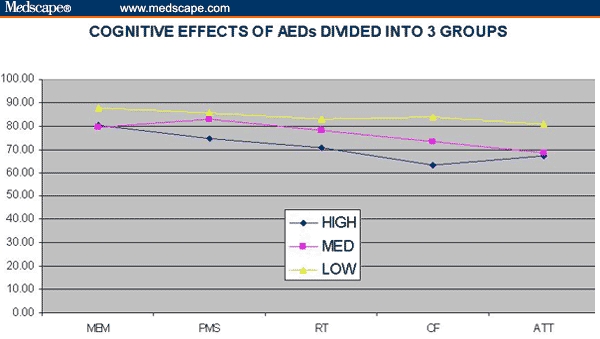

This analysis suggests that in terms of neurocognitive effects, LMTG performs best, followed – in order – by OCBZ, LIT, TPM, VPA, and then CBZ. It also suggested 2 clusters of AEDs: LMTG and OCBZ, with low toxicity; and TPM, VPA, and CBZ, with high toxicity. LIT stands by itself in-between, with “medium” toxicity. Collapsing the cohort into 3 groups, we observed even more dramatic differences (Table 3, Figure 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of Drugs With High, Medium, and Low Neurotoxicity

| Test Score | High | Medium | Low | F | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 72 | 31 | 57 | F | P < |

| Neurocognition Index | 74.47 | 78.32 | 85.79 | 5.32 | .006 |

| Memory | 80.39 | 79.53 | 87.93 | 1.74 | .179 |

| Psychomotor speed | 74.50 | 83.08 | 85.75 | 5.70 | .004 |

| RT | 70.78 | 78.32 | 83.00 | 3.87 | .023 |

| Cognitive flexibility | 63.28 | 73.25 | 83.93 | 6.45 | .002 |

| Complex attention | 67.32 | 68.36 | 80.78 | 2.73 | .068 |

| Verbal memory | 47.36 | 46.56 | 48.06 | 0.51 | .603 |

| Visual memory | 41.10 | 42.60 | 44.83 | 5.18 | .007 |

| Finger tapping | 91.74 | 101.03 | 99.50 | 2.67 | .073 |

| Symbol-digit coding | 37.46 | 47.68 | 48.16 | 7.22 | .001 |

| Stroop simple RT* | 427.39 | 353.74 | 364.89 | 2.12 | .123 |

| Stroop complex RT* | 771.67 | 691.48 | 675.49 | 4.70 | .010 |

| Stroop part 3 RT* | 871.50 | 802.66 | 802.61 | 1.86 | .159 |

| Stroop test errors* | 4.30 | 3.29 | 4.02 | 0.33 | .716 |

| Shifting attention test correct | 35.36 | 40.60 | 46.02 | 8.69 | .000 |

| Shifting attention test errors* | 16.95 | 13.39 | 10.06 | 4.89 | .009 |

| Shifting attention test RT* | 1152.36 | 1121.41 | 1087.12 | 0.85 | .430 |

| Shifting attention test efficiency* | 2.09 | 2.36 | 1.50 | 4.94 | .008 |

| CPT Correct | 37.42 | 38.09 | 39.15 | 2.92 | .057 |

| CPT Errors* | 8.75 | 3.93 | 2.32 | 2.60 | .077 |

| CPT RT* | 524.01 | 507.40 | 444.60 | 4.28 | 0.015 |

RT = reaction time; CPT = continuous performance test

An asterisk indicates tests on which a lower score is better than a higher score.

Figure 3.

Cognitive effects of antiepileptic drugs divided into 3 groups.

Discussion

We present the spectrum of AED cognitive effects, from studies of normal volunteers and epilepsy patients, and the rank order of AEDs/mood stabilizers from our clinical series of bipolar patients.

The results were virtually the same. The older AEDs, CBZ and VPA, and the new one, TPM, had the most cognitive toxicity. LMTG and OCBZ had the least, and LIT was in the middle. The various psychotropic anticonvulsants exercised cognitive effects on patients with bipolar disorder, for better or worse, just as they would in normal volunteers and patients with epilepsy.

The relative neurocognitive effects of AEDs in epileptic patients were difficult to establish because of the inherent difficulty of evaluating small drug-related differences in patients with a brain disorder, many of whom already have cognitive impairments. Epilepsy, by itself, is sometimes associated with blunting of motor performance, cognitive ability, or other aspects of personality. It can be difficult to dissociate drug effects in epileptic patients from the psychological effects of the disease for which the drugs were originally prescribed. The measures of attention, memory, motor performance, and processing speed that are most commonly used in neurocognitive studies are also known to be negatively affected in epileptic populations not receiving drugs.[18,31,32]

The major psychiatric disorders are also associated with cognitive impairment. Patients with bipolar disorder tend to be impaired in measures of attention, memory, and executive control functions.[33] In fact, their cognitive deficits often persist even when they are euthymic.[34,35] This is true even of the best clinical responders, “patients in excellent clinical remission and who reported good social adaptation.[36]”

Cognitive studies of neuropsychiatric patients are prone, therefore, to at least a degree of ambiguity.[37,38] Nevertheless, regardless of a formidable signal/noise problem, a pattern has emerged. The literature suggests that AEDs that are predominantly GABAergic (barbiturates, benzodiazepines, VPA, gabapentin, tiagabine, and vigabatrin) are relatively sedating, and associated with fatigue, cognitive blunting, and weight gain. Drugs whose action is predominantly glutamatergic (eg, felbamate and LMTG) are associated with activation, weight loss, antidepressant effects, and cognitive sparing.[39] This pattern is consistent with results of the present investigation. In terms of cognitive effects, LMTG, for example, is clearly superior to VPA. VPA, despite its mood-stabilizing effects, is prone to negative cognitive effects in various dimensions – learning, memory, attention, and motor speed.[21,24]

That LMTG has a favorable cognitive profile in patients with epilepsy (and normal volunteers) has been established in a relatively large number of studies.[40] LMTG is structurally unrelated to the other anticonvulsants. In direct comparisons to DPH, phenobarbital, and CBZ, it has little cognitive or behavioral toxicity, but rather positive effects on “quality of life” and patient perceptions.[41–44] Even in mentally retarded people, LMTG is said to have “impressive” behavioral effects (less lethargy, reduced hyperactivity, improved social interactions, more appropriate speech, and less irritability).[45] The neurocognitive effects of LMTG in this study were apparent in visual memory, psychomotor speed, reaction time, cognitive flexibility, and sustained attention.

Data from this clinical series of bipolar patients suggested that OCBZ is only marginally inferior to LMTG. This, too, is consistent with data from epileptic patients. In patients with seizure disorders, OCBZ is better tolerated than its parent compound, CBZ. In patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy, and in normal subjects, neurocognitive performance on OCBZ is superior to CBZ.[40,46]

Studies in epileptic patients and normal volunteers indicated that TPM has the potential for diffuse cognitive toxicity, similar to that of CBZ and VPA. Psychomotor slowing is the most common cognitive complaint in patients treated with TPM.[47,48] It has been associated with significant declines in measures of attention and fluency, processing speed, language, perception, and working memory.[26,49,50] In one series, “the majority of the side effects were related to behavioral and cognitive difficulties.[51]”

The results of this investigation indicated that in patients with bipolar disorder, LMTG, and to a lesser degree, OCBZ, are relatively “clean” drugs, at least in terms of cognitive toxicity. The study authors acknowledge the weakness of the study, primarily its cross-sectional approach. A prospective study with a random assignment of patients would obviously be the preferred method. Nevertheless, the fact that our observations are consistent with a substantial literature in epilepsy patents and normal controls supports the validity of the patterns described.

In the epilepsy literature, it is noted that AEDs with a proclivity to cognitive toxicity tend to be less well tolerated by patients, and are more likely to induce behavioral side effects. This clinical series did not generate data to address issues, such as quality of life, or patients' subjective experience of cognitive impairment. If, however, it is fair to extrapolate from one patient group to another, lower rates of compliance with medications that have cognitive side effects should occur in bipolar patients as well. This would be an interesting question to pursue in bipolar patients.

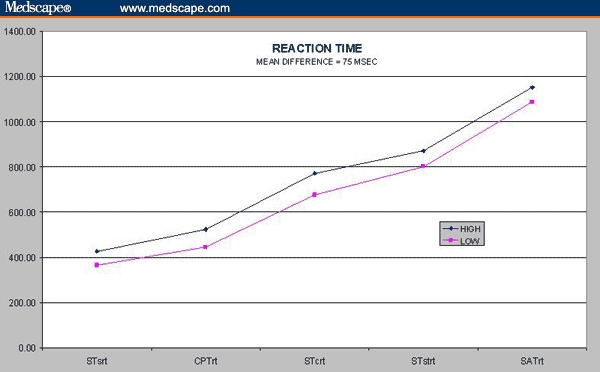

One problem with laboratory studies of cognition in neuropsychiatric patients is that small but statistically significant differences in cognitive test scores may not be meaningful to patients or impressive to prescribing physicians. This is the problem of “clinical salience.” What, exactly, is the significance of small differences, such as those that we have discerned? The illustration in Figure 4 addresses that point with respect to patients' reaction time. There are 5 reaction time measures in CNSVS, in the Stroop test, the continuous performance test, and the shifting attention test. If we compare the reaction times of patients in the “low-toxicity” group (LMTG and OCBZ) with patients in the “high-toxicity” group (CBZ, TPM, and VPA), there is an average difference of 75 mseconds in favor of the former (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reaction time.

What is the importance of a 75-msecond difference? It is only about 7 ft, in a car traveling 60 mph. Figure 4, however, indicates that the reaction time difference is more or less constant in every kind of mental operation measured in these 3 tests, from simple reaction time on the Stroop test to the speed-accuracy calculation that is necessary on the shifting attention test. What is the cumulative impact, then, of a 75-msecond difference when it is attached to every mental operation that a person executes during the course of a day?

Patients with bipolar disorder, as epileptic patients, are prone to mild cognitive impairment simply by virtue of their illness. When prescribing medications for such patients, one ought to attend to the relative effects that the drugs have on their cognitive status.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eye only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Funding Information

This research was funded by North Carolina Neuropsychiatry, PA, in Chapel Hill and Charlotte. No external support was sought or received on behalf of this research.

Contributor Information

C. Thomas Gualtieri, North Carolina Neuropsychiatry Clinics, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; CNS Vital Signs, LLP, Chapel Hill, North Carolina Email: tg@ncneuropsych.com.

Lynda G. Johnson, North Carolina Neuropsychiatry Clinics, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

References

- 1.MacLeod CM, Dekabian AS, Hunt E. Memory impairment in epileptic patients: selective effects of phenobarbital concentration. Science. 1978;202:1102–1104. doi: 10.1126/science.715461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meador KJ, Loring DW, Huh K, Gallagher BB, King DW. Comparative cognitive effects of anticonvulsants. Neurology. 1990;40:391–394. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.3_part_1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gualtieri CT. Philadelphia: Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 2002. Brain Injury and Mental Retardation: Psychopharmacology and Neuropsychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gillham RA, Williams N, Wiedmann KD, Butler E, Larkin JG, Brodie MJ. Cognitive function in adult epileptic patients established on anticonvulsant monotherapy. Epilepsy Res. 1990;7:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90018-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn R, Frye M, Kimbrell T, Denicoff K, Leverich G, Post R. The efficacy and use of anticonvulsants in mood disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:215–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McElroy S, Keck P. Pharmacologic agents for the treatment of acute bipolar mania. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:539–557. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00961-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okuma T, Kishimoto A, Inoue K. Anti-manic and prophylactic effects of carbamazepine on manic-depressive psychosis. Seishin-Igaku. 1975;17:617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1973.tb02661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S. Comparison of the antimanic efficacy of carbamazepine and chlorpromazine: a double-blind controlled study. Psychopharmacology. 1979;66:211–217. doi: 10.1007/BF00428308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Post RM, Uhde TW, Ballenger JC. Efficacy of carbamazepine in affective disorders: implications for underlying physiological and biochemical substrates. In: Emrich HM, Okuma T, Muller AA, editors. Anticonvulsants in Affective Disorders. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1984. pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sachs G, Thase M. Bipolar disorder therapeutics: maintenance treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00991-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachs G, Printz D, Kahn D, Carpenter D, Docherty J. The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000. Postgrad Med. 2000:1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuppaeck C, Barnas C, Miller C, Schwitzer J, Fleishhacker WW. Carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10:39–42. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winterer G, Hermann W. Valproate and the symptomatic treatment of schizophrenia spectrum patients. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33:182–188. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-12981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowden CL, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, et al. Maintenance clinical trials in bipolar disorder: design implications of the divalproex-lithium-placebo study. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33:693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fatemi S, Rapport D, Calabrese J, Thuras P. Lamotrigine in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder 2649. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:522–527. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koller WC. Sensory symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1984;34:957–959. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suppes T, Brown E, McElroy S, et al. Lamotrigine for the treatment of bipolar disorder: a clinical case series. J Affect Disord. 1999;53:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson P, Huppert F, Trimble M. Anticonvulsant drugs, cognitive function and memory. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1980;80:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1980.tb02354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrewes DG, Bullen JG, Tomlinson L, Elwes RD, Reynolds EH. A comparative study of the cognitive effects of phenytoin and carbamazepine in new referrals with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1986;27:128–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Dougherty M, Wright FS, Cox S, Walson P. Carbamazepine plasma concentration. Relationship to cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:863–867. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1987.00520200065021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gallassi R, Morreale A, Lorusso S, Procaccianti G, Lugaresi E, Baruzzi A. Carbamazepine and phenytoin. Comparison of cognitive effects in epileptic patients during monotherapy and withdrawal. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:892–894. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320082020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prevey ML, Mattson RH, Cramer JA. Improvement in cognitive functioning and mood state after conversion to valproate monotherapy. Neurology. 1989;39:1640–1641. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.12.1640-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duncan JS, Shorvon SD, Trimble MR. Effects of removal of phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate on cognitive function. Epilepsia. 1990;31:584–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg JF, Burdick KE. Cognitive side effects of anticonvulsants. J Clin Psychol. 2001;62:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meador KJ, Loring DW, Ray PG, et al. Differential cognitive and behavioral effects of carbamazepine and lamotrigine. Neurology. 2001;56:1177–1182. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin R, Kuzniecky R, Ho S, et al. Cognitive effects of topiramate, gabapentin, and lamotrigine in healthy young adults. Neurology. 1999;52:321–327. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG, Benedict KB. Reliability and validity of a brief computerized neurocognitive screening battery. Program and abstracts of the International Neuropsychological Society Annual Meeting; February 4, 2004; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG, Benedict KB. Reliability and validity of a new computerized test battery. Program and abstracts of the International Neuropsychological Society Annual Meeting; February 4, 2004; Baltimore, Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gualtieri CT, Johnson LG, Benedict KB. A computerized cognitive screening battery for psychiatrists. Program and abstracts of the American Psychiatric Association 2006 Annual Meeting; April 20, 2006; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benedict KB, Benson J. The use of CNSVS in college students with primary attention and/or learning disorders. Program and abstracts of the 16th Annual Postsecondary Disability Training Institute (PTI); July 17, 2004; Mount Snow, Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews CG, Harley JP. Differential psychological test performances in toxic and nontoxic adult epileptics. Neurology. 1975;25:184–188. doi: 10.1212/wnl.25.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loiseau P, Strube E, Broustet D, Buttlellochi S, Gomeni C, Morselli PL. Learning impairment in epileptic patients. Epilepsia. 1983;24:183–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott J, Stanton B, Garland A, Ferrier IN. Cognitive vulnerability in patients with bipolar disorder. Psychol Med. 2000;30:467–472. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilder-Willis KE, Sax KW, Rosenberg HL, Fleck DE, Shear PK, Strakowski SM. Persistent attentional dysfunction in remitted bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:58–62. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.030202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basso MR, Lowery N, Neel J, Purdie R. Neuropsychological impairment among manic, depressed and mixed-episode inpatients with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychology. 2002;16:84–91. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.16.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubinsztein JS, Michael A, Paykel E, Sahakian BJ. Cognitive impairment in remission in bipolar affective disorder. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1025–1036. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dodrill CB, Troupin AS. Neuropsychological effects of carbamazepine and phenytoin: a reanalysis. Neurology. 1991;41:141–143. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dodrill CB. Problems in the assessment of cognitive effects of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 1992;33:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ketter T, Post R, Theodore W. Positive and negative psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in patients with seizure disorders. Neurology. 1999;53:S53–S67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldenkamp AP, Boon PA, Deblaere K, et al. Usefulness of language and memory testing during intracarotid amobarbital testing: observations from an fMRI study. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;108:147–152. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gillham R, Kane K, Bryant-Comstock L, Brodie MJ. A double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy with health-related quality of life as an outcome measure. Seizure. 2000;9:375–379. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith D, Chadwick D, Baker G, Davis G, Dewey M. Seizure severity and the quality of life. Epilepsia. 1993;34:S31–S35. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb05921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meador K, Baker G. Behavioral and cognitive effects of lamotrigine. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:S44–S47. doi: 10.1177/0883073897012001101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marciani M, Stanzione P, Mattia D, et al. Lamotrigine add-on therapy in focal epilepsy: electroencephalographic and neuropsychological evaluation. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1998;21:41–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ettinger A, Weisbrot D, Saracco J, Dhoon A, Kanner A, Devinsky O. Positive and negative psychotropic effects of lamotrigine in patients with epilepsy and mental retardation. Epilepsia. 1998;39:874–877. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mecarelli O, Vicenzini E, Pulitano P, et al. Clinical, cognitive, and neurophysiologic correlates of short-term treatment with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and levetiracetam in healthy volunteers. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1816–1822. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin R, Meador K, Turrentine L, et al. Comparative cognitive effects of carbamazepine and gabapentin in healthy senior adults. Epilepsia. 2001;42:764–771. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.33300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tatum WOt, French JA, Faught E, et al. Postmarketing experience with topiramate and cognition. Epilepsia. 2001;42:1134–1140. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.41700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee S, Sziklas V, Andermann F, et al. The effects of adjunctive topiramate on cognitive function in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2003;44:339–347. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.27402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dooley J, Camfield P, Smith E, Langevin P, Ronen G. Topiramate in intractable childhood onset epilepsy – a cautionary role. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26:271–273. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohamed K, Appleton R, Rosenbloom L. Efficacy and tolerability of topiramate in childhood and adolescent epilepsy: a clinical experience. Seizure. 2000;9:137–141. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]