Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Tuberculoma of the liver is rare in an immunocompetent individual. We report a 26-year-old man with upper abdominal pain, abnormal liver function, and raised inflammatory markers. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a mixed attenuation lesion measuring 6 × 5 cm occupying most of the left lobe of the liver. Subsequent histology and culture confirmed tuberculous abscess. Following antituberculous therapy, repeat CT scan revealed complete resolution of the initial findings. This case illustrates the diagnostic difficulties of hepatic tuberculosis (TB) and the importance of considering TB in patients with hepatic lesions.

Introduction

TB is a growing problem worldwide; consequently, it is vital to recognize the more unusual presentations of this disease. Intra-abdominal TB has a high mortality, but it is a difficult diagnosis to make, often requiring laparotomy. Liver tuberculoma is, in particular, rare, with fewer than 100 cases reported in the literature, most of which are secondary and associated with miliary TB.[1] We present a case of primary hepatic tuberculoma in an immunocompetent host and illustrate how these cases can be managed nonsurgically.

Readers are encouraged to respond to George Lundberg, MD, Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: glundberg@medscape.net

Case Report

A 26-year-old Ugandan engineering student presented with a 5-month history of upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia, and weight loss. Clinical examination revealed epigastric and right upper quadrant tenderness, with a smooth tender 4-cm hepatomegaly. Initial blood results revealed a microcytic anemia (Hb 10.3 g/dL, MCV 73.4 fl), raised inflammatory markers (ESR 126, CRP 178 mg/L), and an elevated alkaline phosphatase (153 IU/L).

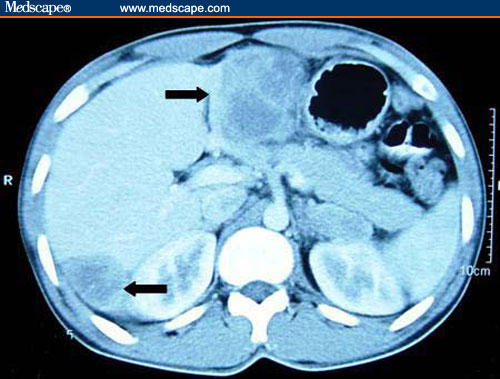

He went on to have a transabdominal ultrasound, which demonstrated a 6.5-cm heterogenous mass in the left lobe of the liver with ultrasound features suggestive of hepatocellular carcinoma. Subsequent abdominal CT confirmed a mixed attenuation lesion measuring 6 × 5 cm, occupying most of the left lobe of the liver, and a smaller lesion in the right lobe (Figure 1) Multiple sub-1-cm lymph nodes were also found surrounding the small bowel mesentery. The appearances were suggestive of either lymphoma or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Contrast enhanced abdominal CT scan revealing a 6-cm by 5-cm mixed attenuating lesion in the left lobe, and a 4-cm lesion in the right lobe of the liver.

Serum tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and CA 19-9) were negative, and a guided liver biopsy was performed. Histology revealed granulomatous inflammation associated with Langhans giant cells (Figure 2) suggesting mycobacterial infection. Aspiration of 100 mL of thick purulent material was performed under ultrasound guidance. Although Ziehl-Nielsen stain failed to demonstrate acid-fast bacilli, culture of the samples subsequently demonstrated the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, sensitive to quadruple therapy. Plain chest radiology and thoracic CT revealed no evidence of pulmonary TB. Subsequent HIV serology was negative.

Figure 2.

Histology revealing a granulomatous inflammation, little preservation of liver architecture, and presence of Langhans cells (arrow). (200× magnification, H and E stain)

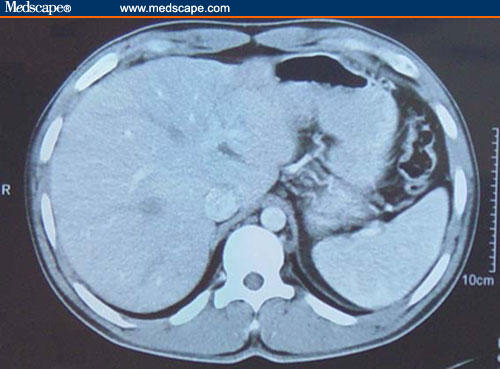

The patient was commenced on ethambutol, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and rifampicin. Within 3 months of therapy, the patient was asymptomatic with normal serum inflammatory markers. Repeat CT scan following 6 months of antituberculous therapy revealed a complete resolution of the lesion (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Contrast enhanced abdominal CT following 6 months of quadruple therapy, revealing a complete resolution of the lesions.

Discussion

Hepatic TB has been classified by Levine[2] into: (a) miliary TB; (b) pulmonary TB with hepatic involvement; (c) primary liver TB; (d) focal tuberculoma or abscess; or (e) tuberculous cholangitis. The most common form of hepatic involvement is the miliary form of TB, in which hematogenous spread is through the hepatic artery.[1] Hepatic involvement can be seen in up to 80% of disseminated cases of TB. Isolated tuberculous involvement of the liver is considered rare because of the low oxygen tension within the liver, making it unfavorable for mycobacterial growth. Primary hepatic TB in the absence of immunocompromise is extremely rare.

Tuberculous cholangitis may present with jaundice and fever.[3] However, the presentation of a focal liver abscess is often much less specific, with right upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever, night sweats, anorexia, and weight loss. The most frequent examination findings include abdominal tenderness with or without a palpable mass and occasional jaundice.

Laboratory investigations often reveal an elevated alkaline phosphatase in the presence of normal alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase.[1] Less specific findings include anemia, hypoalbuminemia, and hyponatremia.[1]

Imaging studies can pose a diagnostic challenge, with a number of potential differential diagnoses, including primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Hypoechoic nodules are usually seen at ultrasonography,[4] though rarely the appearances may appear hyperechoic. CT findings usually reveal a round hypodense lesion with slight peripheral enhancement and, occasionally, areas of focal calcification.[4] Noninvasive diagnosis is therefore difficult, and up to 90% of cases require a laparotomy to make the diagnosis.[5] Despite the rarity of this condition, primary hepatic tuberculoma should be considered among the differential diagnoses of space-occupying lesions of the liver.

The histologic findings often achieve the diagnosis, with features of caseating granulomatous necrosis. Langhans-type giant cells are often present with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate including plasma cells, eosinophils, and lymphohistiocytic cells.

It is clear from the literature that a histologic diagnosis is imperative in these cases, but avoiding laparotomy is ideal. In the reported case, a guided biopsy of the lesion was performed, and the resulting histology and cultures confirmed the diagnosis of hepatic tuberculoma without the need for a laparotomy.

Low sensitivity of both acid-fast staining (from 0% to 45%) and culture (from 10% to 60%) mean diagnosis can still be difficult.[2] However, the use of polymerase chain reaction to directly detect the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is increasing and may improve sensitivity rates.

Treatment of hepatic TB is by quadruple therapy for 1 year, though there are often signs of clinical improvement within 2-3 months. The use of percutaneous drainage has also been advocated. Mustard and colleagues[6] suggested features associated with successful drainage included: (1) unilocular abscess; (2) safe access route for instillation of drainage catheter; and (3) a sterile uncontaminated compartment.

Hepatic tuberculoma are rare, but with the increasing worldwide incidence of TB, it is a diagnosis that must be considered, especially in patients considered at high risk. This case illustrates the minimally invasive investigation, diagnosis, and treatment of a primary hepatic tuberculoma.

Contributor Information

Matthew J. Brookes, Gastroenterology Unit, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Melanie Field, Gastroenterology Unit, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Dee M. Dawkins, Department of Radiology, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Joan Gearty, Department of Histopathology, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

Paul Wilson, Gastroenterology Unit, City Hospital, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

References

- 1.Rab SM, Beg MZ. Tuberculous liver abscess. Br J Clin Pract. 1977;31:157–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine C. Primary macronodular hepatic tuberculosis: US and CT appearances. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:307–309. doi: 10.1007/BF01888805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratanarapee S, Pausawasdi A. Tuberculosis of the common bile duct. HPB Surg. 1991;3:205–208. doi: 10.1155/1991/42843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan HS, Pang J. Isolated giant tuberculomata of the liver detected by computed tomography. Gastrointest Radiol. 1989;14:305–307. doi: 10.1007/BF01889223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliva A, Duarte B, Jonasson O, Nadimpalli V. The nodular form of local hepatic tuberculosis. A review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:166–173. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199004000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mustard RA, Mackenzie RL, Gray RG. Percutaneous drainage of a tuberculous liver abscess. Can J Surg. 1986;29:449–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]