Abstract

Caregiving has only recently been acknowledged by the nation as an important topic for millions of Americans. A psychological or sociological approach to care-giving services has been most often applied, with little attention to the population-based public health outcomes of caregivers.

We conceptualize caregiving as an emerging public health issue involving complex and fluctuating roles. We contend that caregiving must be considered in the context of life span needs that vary according to the ages, developmental levels, mental health needs, and physical health demands of both caregivers and care recipients.

THE GOAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH in the United States is to promote healthy individuals living in healthy communities, pursuing quality of life rather than simply absence of disease. The Institute of Medicine1 designates the general functions of public health as assessment, policy, and assurance. Quality research is an integral part of each of these endeavors. Typically, whereas the funding and authority for public health initiatives come from the federal government or state governments, communities deal with most of the burdens and practicalities of public health issues.

Caregiving has become an issue that affects the quality of life for millions of individuals and demands attention from every community.2 Historically, scientists and practitioners alike rarely thought of caregiving as a public health matter. Studies on caregiving often focused on social and psychological dimensions, primarily on the stress associated with caregiving. However, over the past 25 years, considerable scholarship has addressed multiple dimensions of caregiving. Pioneering work by Shanas,3,4 Sussman,5 and Brody6–8 helped map an understanding of those who provide care and the richness and paucity of caregiving relationships. More recent investigations have addressed coping strategies9 and the demands of caring for people with dementia,10 and a growing body of literature has focused on health concerns associated with caregiving11 such as illness and caregiver burden.12

However, even with this abundance of relatively new research, surprisingly little attention has been focused on framing caregiving from a public health standpoint. Therefore, we sought to conceptualize caregiving as an emerging public health issue, with the contention that there is considerable overlap in the individual needs of caregivers—the foundation of an enormous system of care in the United States and around the world—and the public health needs of many communities and their members.

DEMOGRAPHIC AND HISTORICAL FORCES

As the nature and functions of caregiving have evolved, it has become a critical and salient issue in the lives of individuals in all demographic categories. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, caregiving was typically short term. In 1900, before antibiotics were introduced, many people died before reaching the age of 45 years from infection-related complications. Today, average life expectancy in the United States is approaching 80 years, and most people die of complications resulting from chronic conditions.13 Improvements in medicine and technology have not only ensured longer lives but also dramatically increased the need for long-term caregiving.

Within the US health care system, a shortage of nurses and other health care workers has been accompanied by increasing costs associated with hospitalization and long-term care, leading to patients with involved care needs being discharged from hospitals more rapidly than in the past. In addition, recent medical advances are saving the lives of thousands of infants who will require lifelong care for disabilities or chronic illnesses. Since the 1960s, there has been a movement away from institutionalization and a push to provide care for individuals within the community. The Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision encouraged this trend, mandating that states provide care for the elderly and individuals with disabilities in the least restrictive environment possible.14

As a result of such pressure from the health care system and the courts, dependence on family and other sources of caregiving has reached a peak. In the past, the overwhelming majority of caregivers were women who were not employed outside the home. Today, women make up half of the workforce but continue to face the bulk of caregiving responsibilities. In addition, many working women are caring simultaneously for their children and their parents, and this and other variations of intergenerational care are placing increasing pressure on the home care system that women anchor. With myriad responsibilities, family caregivers need and deserve support from the nation’s public health system to maintain their own health.

The “graying” of the baby boom generation, whose members began to turn 50 years old in 1996, will drive future caregiver needs and caregiving solutions. Baby boomers are projected to live longer than any previous generation, and the number of people aged 65 years or older is expected to double between 2000 and 2030.15 Elderly people will also increase as a proportion of the population, and people aged older than 85 years will be the fastest growing segment of that group. Other dynamics within the older population suggest more intensive caregiving demands as well. For example, today’s increased life expectancies mean that many 65-year-olds will be caring for their 90-year-old parents.

One of the miracles of the 20th century was the increase in life expectancy among people with disabilities. For instance, first-year survival rates of children with Down syndrome increased from 50% during 1942 to 1952 to 91% during 1980 to 1996,16 and people with this disability are now living into old age. Similarly, prior to World War II, the average life expectancy for someone with a spinal cord injury was 14 months.17 Today people with spinal cord injuries can expect to live relatively long lives. For most of our history, parents outlived their disabled children; that is no longer the case.

PUBLIC HEALTH FUNCTIONS

The framework outlined in The Future of Public Health,1 which identified a variety of public health functions at the local, state, and national levels, is instructive for conceptualizing caregiving in the public health arena. As noted earlier, a major function of public health is to create the scientific foundation necessary to inform policies and interventions. Public health science often involves epidemiological investigations addressing the magnitude, characteristics, and distribution of a given problem as well as health disparities and determinants of health.

A 2004 national survey conducted by the National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) and the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP)18 gathered population-based data on characteristics of caregiving and caregivers in the United States. The survey results showed that 21% of people aged older than 18 years were caregivers, representing 44.4 million Americans. Seventy-nine percent of care recipients were aged 50 years or older; 20% were aged 18 to 49 years. Duration of care averaged 4.3 years.

The joint NAC and AARP study defined 5 levels of caregiving. “Level 1” caregivers devoted relatively few hours each week (a mean of 3.5) to providing care and provided no care in the form of help with activities of daily living (ADLs). “Level 5” caregivers were those with the heaviest burden (a mean of 87.2 hours per week), providing help with at least 2 ADLs and more than 40 hours of care each week.18

Intensity of care provided predicted a number of problems related to health. For example, 35% of level 5 caregivers reported their health as fair or poor, compared with 12% of level 1 caregivers. Also, level 5 caregivers were more likely to report significant physical strain than were level 1 caregivers (46% vs 3%). Finally, level 5 caregivers were 4 times more likely than were level 1 caregivers to report significant emotional strain.

Although the joint NAC and AARP investigation provides sound national data, there is a lack of knowledge about variations in caregiving health effects from state to state. Because rates of disability vary considerably between states, and because elderly populations are increasing rapidly in some states, it is reasonable to expect that caregiving demands would mirror that study’s findings by increasing proportionately.

The health of both caregivers and care recipients has been very much on the minds of investigators. It has been shown, for example, that the chief risk of institutionalization is not a decline in the health of care recipients but a decline in the health of family caregivers themselves.19 It has also been shown that individuals with good sources of caregiving support are less likely to be institutionalized than care recipients without such support.20 Absence of family caregiving is a leading predictor of institutionalization. In addition, studies indicate that levels of disability are much higher among individuals who are institutionalized than among those who are not.

Furthermore, several recent studies have confirmed disparities in health and preventive health practices among caregivers, with caregivers who provide more intense caregiving services appearing to be at greater risk. For example, Shaw et al.10 found that caregivers experiencing the physical stress of caring for family members with Alzheimer’s disease who required assistance with ADLs reported poorer health than did family members dealing with the psychological stress presented by the disease.

Schulz et al.11 and Schulz and Beach22 examined the results of the Caregiver Health Effects Study, which focused on caregivers reporting mental and physical strain associated with caregiving. In comparison with those who did not report strain, those who reported strain were 9-times more likely to report not having enough rest, 5-times more likely to report not having enough time to exercise, and 10-times more likely to report not having enough time to rest when they were sick. In a companion study, Burton et al.23 found that spouses caring for a disabled partner were less likely than spouses not caring for a disabled partner to engage in preventive health behaviors, including getting enough sleep, taking time to recuperate, exercising, eating regular meals, keeping medical appointments, obtaining flu shots, and refilling medicines.

Whereas caregiver morbidity is a primary public health concern, caregiver mortality is also an issue in assessments of end-of-life care. Christakis and Iwashyna21 showed that caregivers whose spouses received hospice care were less likely to die after their spouse’s death than those whose spouses did not receive hospice care. For example, 5.4% of bereaved wives died within 18 months of the death of their husbands when their deceased husbands did not use hospice; 4.9% died when their husband did use hospice.21(p465) Such statistics reflect the need for caregiver support and interventions throughout the caregiving experience and beyond.

As noted earlier, many families struggle with caring for children with disabilities because these children are typically living longer. As with all care situations, there are obviously many dimensions of providing care for a child with a disability. One involves changing expectations and roles; such experiences are well documented, but we need to be mindful that the nature of providing care for children with disabilities is fluid and dynamic. “Normal” expectations regarding these children’s feeding, clothing, and learning behaviors may be complicated when they do not reach milestones and exhibit ADL limitations as they grow older. As an example, unlike many 4-year-olds without disabilities, 4-year-olds with disabilities may not be able to dress themselves.

However, the youth of the parents and the child can be a protective factor early in the child’s life. The parents may be aged 30 years, the child aged 5 years, and the grandparents aged in the 60s. Conversely, 20 years later, the 5-year-old is aged 25 years old, and the parents are aged in the 50s and perhaps caring for their own parents, now aged in the 80s. Families caring for children with disabilities face ongoing adjustments and ongoing stresses, and such situations need further study to frame intergenerational care and disability issues from a public health point of view.

ROLE OF PUBLIC HEALTH IN CAREGIVING

Framing caregiving as a public health issue gives rise to a number of central concerns. First, caregiving is a life span experience, often associated with aging and the roles of spouses and adult children. Although there is, of course, great variability in caregiving experiences, many parents provide care to their children with disabilities, many adult children provide care to their frail or disabled parents, many husbands and wives provide care to their disabled spouses, and child caregivers may provide assistance to their siblings, parents, or grandparents. Thus, caregiving can take a lateral, upward, or downward form.

Second, each experience involves multiple health dynamics. It is our assertion that if the caregiver is healthy, the quality of life of the care recipient will be substantially improved. Conversely, a failure in the health of the caregiver may mean that fragile support systems collapse. In many respects, physical and mental health may be at the core of successful caregiving. For example, in the case of a wife whose husband has a terminal illness, the stress of years of providing care may reach a threshold beyond which, however strong and well meaning, she may face chronic health threats associated with caregiving.24

We also contend that the better their health, the more likely caregivers are to sustain their caregiving roles. This hypothesis applies to caregiving roles ranging from caring for a young child to caring for an elderly individual. Intense caregiving lends itself to a variety of public health concerns. For example, caregivers may not obtain routine health care or undergo health screenings, and thus they may encounter health problems that could have been averted. They may become depressed because of the overwhelming demands of caregiving. Or they may exhaust themselves providing transportation in the local community or as the long-distance caregiver of a family member or friend.

The situations just described may contribute to poorer health for the care recipient as well. For instance, if the caregiver falls when moving the care recipient, both may be injured. If the caregiver is depressed or lacks energy and resilience, the care recipient may not get out of the house to participate in social activities, thus reducing his or her quality of life.

MOVING TO A SYSTEMIC VIEW WITHIN PUBLIC HEALTH

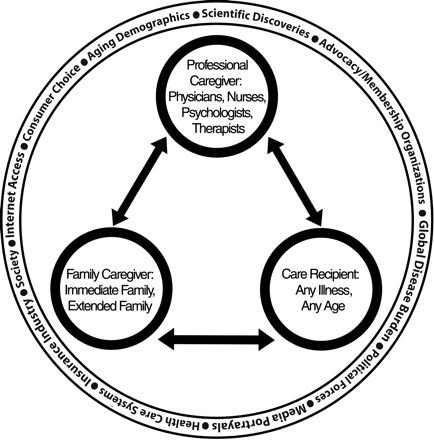

Over the past decade, a conceptual model of care that depicts the complex and often reciprocal nature of the care relationship has been refined.25 This model, which takes into account the strengths and needs of all care partners, features a triadic relationship among the family caregiver, the care recipient, and the professional caregiver. All 3 roles are acknowledged and valued in terms of associated responsibilities and needs. Each party brings to the equation a dedication to participate as a respectful and valuable care team member. Of course, more than one family caregiver or professional caregiver can be and often is involved in care coordination or provision. The triadic model of caregiving allows for recognition of current and potential care partners and their resources in planning for care provision.

We have reconceptualized the care triad within a complex system of variables that influence provision of support or services to caregivers and care recipients (Figure 1 ▶). Relationships among family caregivers, professional caregivers, and the care recipient are embedded in the triad’s framework of prominent forces affecting health and well-being. These forces can include societal, political, and scientific issues that shape the context of care, such as global disease burden, demographic changes, health insurance coverage, and scientific discoveries. Within this framework, the care triad deals with a variety of internal as well as external variables that facilitate or inhibit the care situation, enhancing the chances for success or hindering them.

FIGURE 1—

A triadic model of caregiving: factors influencing the care recipient, family caregiver, and professional caregiver team.

We have identified health dimensions and consequences among family caregivers, professional caregivers, and care recipients, but we have not yet framed the experience of caregiving over the life span as a public health concern. If we were to think about caregiving as residing in the domain of public health, what might be some logical questions? What specific steps would be needed to integrate caregiving into the public health agenda?

First, surveillance and epidemiology are significant functions of public health, and they are concerns of central importance to those attempting to develop policies and practices for caregivers. At present, we have only fragmented population-based knowledge about numbers and characteristics of caregivers. Moreover, we have virtually no knowledge about caregivers at the state level, where policies and programs are generally implemented.

Second, an examination of the characteristics of caregivers would allow us to identify disparities in health between those who do and do not provide care. Moreover, an exploration of health dimensions might allow us to better understand care recipients’ health status, needs, and circumstances.

Third, core definitions of public health center on the use of scientific knowledge to develop and disseminate interventions intended to improve the health of various constituencies. In this case, can public health develop community-based interventions and affect national policies designed to improve the health of caregivers? And can improved caregiver health result in improved health of care recipients?

An additional part of the public health agenda involves promoting programs, services, and solutions for the problems faced by vulnerable groups. The needs of caregivers are served by federal and state legislation, government-funded programs, professionals in health care and social services, and numerous other sources. Because of budget limitations of family caregivers as well as outside funding sources, priority must be given to determining the services and interventions that are most useful to caregivers; that is, there must be an evidence-based approach to caregiver interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

The concept of caregiving is easy to grasp because it is such a familiar part of life. Although knowledge of caregiving and caregivers has increased in many areas, translation of that knowledge has not followed in caregiving practice or policy. We need to reframe our notions about caregiving to remind ourselves of its life span nature. Our attention has with reason been drawn to the needs of the elderly, but that group represents only one segment—albeit a large one—of those who receive and provide care.

The nature of caregiving will become more complex as increasing life expectancies tax the ability of caregivers to provide care. It is clear that caregivers carry a significant burden and face many potentially serious health problems. The challenge for public health systems is to understand more about those caregivers who are particularly vulnerable and why and then to design and implement evidence-based interventions to address identified needs. Researchers need to be at the forefront in uncovering possible risk factors associated with the endless types of caregiving situations. From a public health perspective, it is critically important to identify the hazards of caregiving as well as to develop potential improvements and solutions.

Future research will provide a foundation that supports the public health system in ensuring the delivery of appropriate, targeted services to caregivers. More evidence on efficacy of services will be needed to meet public health’s commitment to ensure quality services. Linking caregivers to available health care and community services can help promote their health. Moreover, family caregiving, which depends on deep relationships within the context of family or friendship, can be strengthened through strong bonds with community, agency, or professional caregivers.26 Because a central goal of public health is to reduce inequities within the health care system, advocacy and legislation may be necessary for overlooked groups of caregivers.

Caregiving is an emerging public health concern that will personally affect virtually every individual. The needs of caregivers must be acknowledged by the country’s public health officials and addressed in state and local caregiver-directed programs. Caregiving, as a critical public health issue facing our nation, and caregivers, as an increasingly significant portion of the population, are worthy of the attention of the country’s public health system.

Figure 2.

A young boy and his sibling walk around a camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) at the Paico IDP camp in Gulu, Uganda. Nearly 2 million people have been forced to flee their homes and up to 12 000 people have been killed in 2 decades of fighting during Northern Uganda’s civil war. Photograph by Jeff Hutchens.

Acknowledgments

Ronda C. Talley wishes to thank former First Lady Rosalynn Carter for her advocacy on behalf of America’s caregivers.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors The authors contributed equally to the conceptualization and completion of this article.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1988.

- 2.Talley RC, Crews J, Dorn P, Silvernail J, Hunt G, Zeitzer J. Caregiving in America as an emerging public health issue: surveillance and response by the nation’s public health system. Paper presented at: Second National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities Conference, July 2004, Washington, DC.

- 3.Shanas E. The family as a social support system in old age. Gerontologist. 1979;19:169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanas E. Social myth as hypothesis: the case of the family relations of old people. Gerontologist. 1979;19:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sussman MB. Incentives and the Family Environment for the Elderly: Final Report for the Administration on Aging. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1977.

- 6.Brody EM. Parent care as a normative family stress. Gerontologist. 1985; 25:19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brody EM. Mental and Physical Health Practices of Older People: A Guide for Professionals. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1985.

- 8.Brody EM. Informal support systems in the rehabilitation of the disabled elderly. In: Brody SJ, Ruff GE, eds. Aging and Rehabilitation: Advances in the State of the Art. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1986: 104–123.

- 9.Pearlin LI. Conceptual strategies for the study of caregiver stress. In: Light E, Niederehe G, Lebowitz BD, eds. Stress Effects on Family Caregivers of Alzheimer’s Patients: Research and Interventions. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1994:3–24.

- 10.Shaw WS, Patterson TL, Semple SJ, et al. Longitudinal analysis of multiple indicators of health decline among spousal caregivers. Ann Behav Med. 1997; 19:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schulz R, Newsom J, Mittelmark M, Burton L, Hirsch C, Jackson S. Health effects of caregiving: the Caregiver Health Effects Study: an ancillary study of the Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Behav Med. 1997;19:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarit SH, Stephens MA, Townsend A, Greene R. Stress reduction for family caregivers: effects of adult day care use. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53: S267–S277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Family Caregiving Alliance, National Center on Caregiving. Family caregiving and public policy, principles for change. Available at: http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=788. Accessed January 18, 2006.

- 14.Fox-Grage W, Coleman B, Folkemer D. The states’ response to the Olmstead decision: a 2003 update. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org/programs/health/forum/olmstead/2003/03olmstd.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2006.

- 15.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2000: key indicators of well-being. Available at: http://agingstats.gov/chartbook2000/population.html. Accessed February 1, 2006.

- 16.Yang Q, Rasmussen SA, Friedman JM. Mortality associated with Down’s syndrome in the USA from 1983 to 1997: a population-based study. Lancet. 2002; 359:1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mentor R. Spinal cord injury and aging: exploring the unknown. J Am Paraplegia Soc. 1994;16:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caregiving in the US. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Caregiving/AARP; 2004.

- 19.Horowitz A. Family caregiving to the frail elderly. In: Lawton MP, Maddox G, eds. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1985:194–246. [PubMed]

- 20.Barney JL. The prerogative of choice in long-term care. Gerontologist. 1977; 17:309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christakis NA, Iwashyna TJ. The health impact of health care on families: a matched cohort study of hospice use by decedents and mortality outcomes in surviving, widowed spouses. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:465–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282: 2215–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clipp EC, George LK. Dementia and cancer: a comparison of spouse caregivers. Gerontologist. 1993;33: 534–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moroney RM, Dokecki PR, Gates JJ, et al., eds. Caring and Competent Caregivers. Athens: University of Georgia Press; 1998.

- 26.Talley RC, Travis SS. A commitment to professional caregivers: the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Human Development. Geriatr Nurs. 2004;25:113–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]