Abstract

The history of motorcycle helmet legislation in the United States reflects the extent to which concerns about individual liberties have shaped the public health debate. Despite overwhelming epidemiological evidence that motorcycle helmet laws reduce fatalities and serious injuries, only 20 states currently require all riders to wear helmets. During the past 3 decades, federal government efforts to push states toward enactment of universal helmet laws have faltered, and motorcyclists’ advocacy groups have been successful at repealing state helmet laws. This history raises questions about the possibilities for articulating an ethics of public health that would call upon government to protect citizens from their own choices that result in needless morbidity and suffering.

IN THE FACE OF OVERWHELMING epidemiological evidence that motorcycle helmets reduce accident deaths and injuries, state legislatures in the United States have rolled back motorcycle helmet regulations during the past 30 years. From the jaws of public health victory, the states have snatched defeat. There are many ways to account for the historical arc; we focus here on the enduring impact libertarian and antipaternalistic values may have on US public health policy.

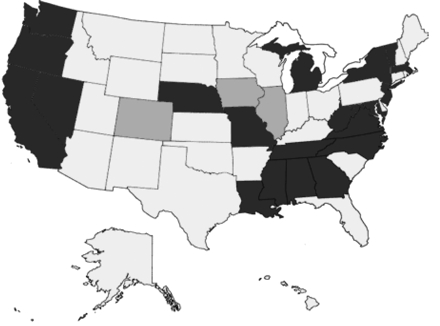

Currently, only 20 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico require all motorcycle riders to wear helmets (Figure 1 ▶). In another 27 states, mandatory helmet laws apply only to minors (aged younger than 18 years or 21 years depending on the state), and 3 states—Colorado, Illinois, and Iowa—have no motorcycle helmet laws. Additionally, 6 of the 27 states with minor-only helmet laws require that adult riders have $10 000 of insurance coverage or that helmets be worn during the first year of riding (Table 1 ▶).1 This uneven patchwork of state regulations on motorcycle helmet use contrasts dramatically with the picture 30 years ago, when 47 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico had passed mandatory helmet laws that applied to all riders.2 The repeal of motorcycle helmet laws has occurred as the United States has moved toward greater statutory regulation of automobile safety. During the past 20 years, every state except New Hampshire has enacted a mandatory seat belt law, and since 1998, the National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has required that all new cars sold in the United States be equipped with dual air bags.3

FIGURE 1—

Legal Protection for Motorcyclists by State, 2006.

Note. Black States have mandatory universal helmet laws; light gray states’ helmet laws cover only minors or some riders; dark gray states have no helmet laws.

Sources. R. G. Ulmer and D.F. Preusser, “Evaluation of the Repeal of Motorcycle Helmet Laws in Louisiana, October 2002,” U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (NHTSA) Report No. HS 809 530; Fast Fred’s Motorcycle Rights e-zine, http://www.fastfreds.com/helmetlawmap.htm.2. Accessed November 22, 2006.

TABLE 1—

Helmet Use Requirements by State: United States, 2006

| States That Require Helmet Use For All Agesa | States That Require Helmet Use for Minors or Some Ridersb | States That Do Not Require Helmet Usec |

| Alabama | Alaska | Colorado |

| California | Arizona | Illinois |

| District of Columbia | Arkansas | Iowa |

| Georgia | Connecticut | |

| Maryland | Delawarea | |

| Massachusetts | Floridab | |

| Michigan | Hawaii | |

| Mississippi | Idaho | |

| Missouri | Indiana | |

| Nebraska | Kansas | |

| Nevada | Kentuckyc | |

| New Jersey | Louisianad | |

| New York | Mainee | |

| North Carolina | Minnesota | |

| Oregon | Montana | |

| Puerto Rico | New Hampshire | |

| Rhode Islandh | New Mexico | |

| South Carolina | North Dakota | |

| South Dakota | Ohiof | |

| Tennessee | Oklahoma | |

| Texasi | Pennsylvaniag | |

| Vermont | ||

| Virginia | ||

| Washington | ||

| West Virginia |

aRequired for riders aged younger than 19 years and helmets must be in the possession of other riders, even though use is not required.

bRequired for riders aged younger than 21 years and for those without $10|000 of medical insurance that will cover injuries resulting from a motorcycle crash.

cRequired for riders aged younger than 21 years, riders operating a motorcycle without an instruction permit, riders with less than one year’s experience, and riders who do not provide proof of health.

dRequired for riders aged younger than 18 years and for those who lack $10 000 in medical insurance coverage. Proof of such an insurance policy must be shown to a law enforcement officer upon request.

eRequired for riders aged younger than 15 years, novices, and those with learner’s permits.

fRequired for riders aged younger than 18 years and for first-year operators.

gRequired for riders aged younger than 21 years and for those aged 21 years and older who have had a motorcycle operator’s license for fewer than 2 years or who have not completed an approved motorcycle safety course.

hRequired for riders aged younger than 21 years and for first-year operators.

iRequired for riders aged 20 years and younger and for those who have not completed a rider training course or who do not have $10 000 of medical insurance coverage.

Source. National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Traffic Safety Facts: Motorcycle Helmet Laws.1

The repeal of motorcycle helmet laws in the United States contradicts a global movement toward enacting mandatory helmet laws; as of 2003, at least 29 countries—including most European Union countries, the Russian Federation, Iceland, and Israel—had passed mandatory helmet laws for motorcycles. Developing countries, including Thailand and Nepal, also have passed helmet laws in recent years. Varying levels of enforcement and other factors, such as the general safety and quality of the roads, influence the effectiveness of these laws in different countries.4 In 1991, the World Health Organization launched a global helmet initiative to encourage motorcycle and bicycle helmet usage worldwide.5 Why then have things taken such a different turn in the United States? We conducted a historical examination of the debates on motorcycle helmet laws in the United States to answer this question. In reporting the results, we address tensions between paternalism and libertarian values in the public health arena—tensions that have come to the fore recently with developments in tobacco policy. As efforts to articulate an ethics of public health advance, it is crucial that the question of paternalism be addressed. The history of motorcycle helmet legislation provides a unique vantage point on that issue.

THE ORIGIN OF MOTORCYCLE HELMET LAWS

Motorcycle racers used crash helmets as early as the 1920s. Helmets were more widely used during World War II, when Hugh Cairns, a consulting neurosurgeon to the British Army, recommended mandatory helmet use for British Service dispatch riders, who carried instructions and battle reports between commanders and the front lines via motorcycles.6 Cairns first became concerned about helmet use after treating the war hero T. E. Lawrence—otherwise known as Lawrence of Arabia—for a fatal head injury suffered during a 1935 motorcycle accident. Cairns later published several landmark articles that used clinical case reports to show that motorcycle crash helmets mitigated the severity of head injuries suffered by military motorcyclists during crashes.7

After World War II, the British government’s Ministry of Transport became the first regulatory agency in the world to establish research-based motorcycle helmet performance standards. During the early 1950s, the ministry offered the British Standards Institute “kite mark” (a diamond-shaped seal) as an indicator of helmet quality and performance.8 In the United States, however, no such standard existed, and ads for American motorcycles invariably showed riders without helmets or goggles. The initial market for these bikes included returning veterans who had learned to ride military-issue Harley-Davidsons while overseas.9 During the late 1940s and early 1950s, motorcycle clubs created an “outlaw” masculine social identity around motorbikes—part of an emerging cultural reaction to the social confines of 1950s suburbia. At the same time, the motorcycle took its place amid the variety of new postwar consumer culture offerings, and many young men took up riding motorcycles as a weekend hobby.10

The 1966 National Highway Safety Act introduced drastic and unwelcome changes to US motorcycle culture. The law, which was introduced after the 1965 publication of Unsafe at Any Speed, Ralph Nader’s scathing indictment of the US auto industry’s vehicle safety standards, included a provision that withheld federal funding for highway safety programs to states that did not enact mandatory motorcycle helmet laws within a specified time frame. This provision was added after a study showed that helmet laws would significantly decrease the rate of fatal accidents. The National Highway Safety Act was passed without debate on the helmet law provision.11 Adoption of this measure drew upon a broader movement within public health to expand its purview beyond infectious disease to “prevention of disability and postponement of untimely death.”12 Several years later, this shift sparked debate on the role of both individual and collective behaviors in contemporary patterns of morbidity and mortality, which led to Marc Lalonde’s New Perspective on the Health of Canadians (1974), the US government’s Healthy People Initiative (1979) and, most famously, John H. Knowles’s controversial but agenda-setting article, “The Responsibility for the Individual,” which asserted that individual lifestyle choices determined the major health risks for Western society.13

As of 1966, only 3 states—New York, Massachusetts, and Michigan—and Puerto Rico had passed motorcycle helmet laws, but between 1967 and 1975, nearly every state passed statutes to avoid penalties under the National Highway Safety Act. By September 1975, California was the only state to not have passed a mandatory helmet law of any kind. This resistance carried weight because California had both the highest number of registered motorcyclists and the highest number of fatal motorcycle crashes.14 Additionally, motorcycle groups in the state had developed into a powerful antihelmet lobby. State legislators made 8 attempts between 1968 and 1975 to introduce helmet legislation, but they were thwarted by vocal opposition from the motorcycle groups.15 In September 1973, when a Burbank councilman proposed a mandatory motorcycle helmet ordinance after the death of a 15-year-old motorcyclist, more than 100 motorcyclists came to the council’s chamber to protest during hearings on the ordinance. The Los Angeles Times reported that the Hells Angels planned to bring “at least 500 members” on the day of the scheduled vote. The councilman then withdrew his proposed ordinance.16

CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES TO MANDATORY HELMET LAWS

As soon as states began to pass mandatory helmet laws, opponents mounted constitutional challenges to them. Some challenges involved appeals in criminal cases against motorcyclists who had been arrested for failing to wear helmets; others were civil suits brought by motorcyclists who alleged that the laws deprived them of their rights. Between 1968 and 1970, high courts in Colorado, Hawaii, Louisiana, Missouri, Massachusetts, New Jersey, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin and lower courts in New York all rejected challenges to the constitutionality of their state motorcycle helmet laws.17 In June 1972, a US District Court in Massachusetts similarly rejected a challenge to the state’s helmet law that was brought on federal constitutional grounds, and in November of that year, the US Supreme Court affirmed this decision on appeal without opinion.18

The constitutional challenges focused principally on 2 arguments: (1) helmet statutes violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or state constitutional equivalents by discriminating against motorcycle riders as a class, and (2) helmet statutes constituted an infringement on the motorcyclist’s liberty and an excessive use of the state’s police power under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or similar state provisions. Only the Illinois Supreme Court and the Michigan Appeals Court accepted these arguments. The Illinois Supreme Court ruled that the helmet laws constituted an infringement on motorcyclists’ rights.

If the evil sought to be remedied by the statute affects public health, safety, morals or welfare, a means reasonably directed toward the achievement of those ends will be held to be a proper exercise of the police power [citations omitted]. However, [t]he legislature may not, of course, under the guise of protecting the public interest, interfere with private rights [citations omitted]. . . . The manifest function of the headgear requirement in issue is to safeguard the person wearing it—whether it is the operator or a passenger—from head injuries. Such a laudable purpose, however, cannot justify the regulation of what is essentially a matter of personal safety.19

The Michigan Appeals Court heard a case brought by the American Motorcycle Association, then the country’s largest organization for motorcyclists, which argued that the state’s motorcycle law violated the due process, equal protection, and right to privacy provisions of the federal constitution. The association cited the US Supreme Court’s birth control decision in Griswold v. Connecticut as authority for establishing a right to privacy. The state attorney general contended that the law did not just concern individual rights and was intended to promote public health, safety, and welfare. Furthermore, the state argued that it had an interest in the “viability” of its citizens and could pass legislation “to keep them healthy and self-supporting.” The Appeals Court, however, countered that “this logic could lead to unlimited paternalism” and found the statute unconstitutional.20 The court also rejected the claim that the state’s power to regulate the highways provided the basis for imposing helmet use.

There can be no doubt that the State has a substantial interest in highway safety . . . but the difficulty with adopting this as a basis for decision is that it would also justify a requirement that automobile drivers wear helmets or buckle their seat belts for their own protection!21

The plaintiff in the Massachusetts District Court case used an argument nearly identical to those that had been successful in Illinois and Michigan: a helmet law was designed solely to protect the motorcyclist.22 The plaintiff’s argument cited John Stuart Mill’s assertion that “the only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others.”23 The District Court rejected this line of reasoning. Although it relied on Mill’s distinction between self-regarding and other-regarding behavior, the court clearly found injuries that resulted from motorcycle riders failing to wear a helmet to be other-regarding harms. Even more striking was that the court found the psychological burden on caregivers to be an other-regarding basis for intervention.

For while we agree with plaintiff that the act’s only realistic purpose is the prevention of head injuries incurred in motorcycle mishaps, we cannot agree that the consequences of such injuries are limited to the individual who sustains the injury. In view of the evidence warranting a finding that motorcyclists are especially prone to serious head injuries . . . the public has an interest in minimizing the resources directly involved. From the moment of the injury, society picks the person up off the highway; delivers him to a municipal hospital and municipal doctors; provides him with unemployment compensation if, after recovery, he cannot replace his lost job, and, if the injury causes permanent disability, may assume the responsibility for his and his family’s continued subsistence. We do not understand a state of mind that permits plaintiff to think that only he himself is concerned.24 [authors’ emphasis]

Although others echoed the Massachusetts decision by using economic—utilitarian—arguments to reject constitutional challenges to helmet laws, some courts upheld motorcycle statutes on the basis of the narrow ground that helmet use affects the safety of other motorists. A Florida US District Court held that a requirement for motorcyclists to wear both helmets and eye protection was not an unreasonable exercise of state police power because “[a] flying object could easily strike the bareheaded cyclist and cause him to lose control of his vehicle,” and “the wind or an insect flying into the cyclist’s eyes could create a hazard to others on the highway.”25

THE BIKER LOBBY ROARS INTO ACTION

Motorcyclists had long been organized—whether they belonged to informal clubs, racing associations under the aegis of the American Motorcycle Association, or “outlaw” biker gangs, such as the Hells Angels—and the passage of motorcycle helmet laws galvanized the groups to become political. During the 1970s, the American Motorcycle Association, which was founded in 1924 as a hobbyist group, organized a lobbying arm to “ . . . coordinate national legal activity against unconstitutional and discriminatory laws against motorcyclists, to serve as a sentinel on federal and state legislation affecting motorcyclists, and to be instrumental as a lobbying force for motorcyclists and motorcycling interests.”26 Additionally, those who identified with the biker culture, including members of outlaw motorcycle gangs and thousands of other men who rode choppers (modified motorcycles with high handlebars and custom detailing), became involved in state-level and national-level groups that advocated the repeal of helmet laws and other limitations to riding motorcycles.27 In its October 1971 issue, Easyriders, a glossy magazine for chopper riders, underscored the need for a national effort.

You, as an individual, can stand on your roof-top shouting to the world about how unjust, how stupid, and how unconstitutional some of the recently passed, or pending, bike laws are—but all you will accomplish is to get yourself arrested for disturbing the peace. Individual bike clubs can go before city councils, state legislatures, and congressional committees, but as single clubs, and unprofessional at the game of politics, their efforts are usually futile. . . We need a national organization of bikers. An organization united together in a common endeavor, and in sufficient numbers to be heard in Washington, DC, in the state legislatures, and even down to the city councils.28

The article went on to ask for $3 donations to the National Custom Cycle Association, a nonprofit organization established by the magazine. By the following February, the organization had members in 44 states and had changed its name to A Brotherhood Against Totalitarian Enactments (ABATE).29

Other state-level groups, which called themselves motorcyclists’ rights organizations, also began to form around the country. The Modified Motorcycle Association, a group of chopper riders founded in 1973 that eschewed the outlaw behavior of Hells Angels, engaged in both antihelmet law political activity and local campaigns against police harassment of bikers.30

In 1975, these groups began to turn the tide against proponents of mandatory helmet laws. Motorcyclists, who had only thus far been successful in the appellate courts of 2 states and in stopping helmet bills in California, had evolved into an organized and powerful national lobby. In June and again in September 1975, hundreds of bikers descended on Washington, DC, where they rode their choppers around the US Capitol to protest mandatory helmet laws. In the post-Water-gate environment, motorcyclists found a newly receptive ear in Congress.31 Representatives of ABATE, the American Motorcycle Association, the Modified Motorcycle Association, and other motorcyclists’ rights organizations were invited to hearings held in July 1975 by the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation to discuss revisions to the National Highway Safety Act.

Recognizing that proponents of motorcycle helmet laws, in the tradition of public health, had used statistical evidence of injury and death to make their case, the first motorcyclist to speak at these hearings, Bruce Davey of the Virginia chapter of ABATE, opened with a frontal attack on such data. He charged that NHTSA had manipulated evidence about the effectiveness of motorcycle helmets. Furthermore, he asserted that helmets actually increased the likelihood of neck injuries.32 Davey then advanced a series of constitutional claims that were rooted in an antipaternalistic ethic, which enshrined a concept of personal liberty, and that bore striking similarity to those that had failed in the judicial arena. In an argument more reflective of cultural attitudes than legal precision, he stated,

The Ninth Amendment [to the US Constitution] says no law shall be enacted that regulates the individual’s freedom to choose his personal actions and mode of dress so long as it does not in any way affect the life, liberty, and happiness of others. We are being forced to wear a particular type of apparel because we choose to ride motorcycles.33

Not surprisingly, the issue of choice emerged as the central theme in the arguments of those opposed to helmet laws, similar to the arguments of women’s reproductive rights advocates. Just as proponents of legalized abortion had argued that they were not pro-abortion but were in favor of a woman’s right to choose whether to terminate a pregnancy, ABATE chapter literature stated “ABATE does not advocate that you ride without a helmet when the law is repealed, only that you have the right to decide.”34

At the end of the hearings, Representatives James Howard (D-NJ) and Bud Schuster (R- PA) said they would support revisions to the National Highway Safety Act that removed the tie between federal funding and state helmet laws. A bill that included these revisions had already been introduced in the House by Stewart McKinney (R-CT), an avid motorcyclist, who remarked,

My personal philosophy concerning helmets can be summed up in three words. It’s my head. Personally, I would not get on a 55-mile-per-hour highway without my helmet. But the fact of the matter is that if I did, I wouldn’t be jeopardizing anyone but myself, and I feel that being required to wear a helmet is an infringement on my personal liberties.35

The prospect of ending a threat to withdraw highway funds attracted the notice of liberal Senator Alan Cranston (D-CA), who signed on as a cosponsor of a Senate bill introduced by archconservative Senators Jesse Helms (R-NC) and James Abourezk (R-SD). On December 13, 1975, the Senate voted 52 to 37 to approve a bill that revised the National Highway Safety Act. The House passed a similar measure. The revisions were incorporated into a massive $17.5 billion bill for increasing highway funds to the states, and the bill was signed by President Gerald Ford on May 5, 1976.36

HELMETLESS RIDERS: AN UNPLANNED PUBLIC HEALTH EXPERIMENT

During the next 4 years, 28 states repealed their mandatory helmet laws. The consequences of these repeals were most succinctly expressed in the September 7, 1978, Chicago Tribune headline “Laws Eased, Cycle Deaths Soar.”37 Overall, deaths from motorcycle accidents increased 20%, from 3312 in 1976 to 4062 in 1977.38 In 1978, NHTSA administrator Joan Claybrook wrote to the governors of states that had repealed their laws and urged them to reinstate the enactments. She cited studies that showed motorcycle fatalities were 3 to 9 times as high among helmetless riders compared with helmeted riders and that head injury rates had increased steeply in states where helmet laws had been repealed.39 “Now that some states have repealed such legislation we have control and experimental groups which when compared show that one of the rights enhanced by repeal is the right to die in motorcycle deaths,” opined an editorialist in the June 1979 issue of the North Carolina Medical Journal.40

For those concerned about public health, the unfolding events were viewed with alarm. In the June 1980 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, Susan Baker, an epidemiologist and director of the Johns Hopkins Injury Prevention Center, compared the situation to one where “scientists, having found a successful treatment for a disease, were impelled to further prove its efficacy by stopping the treatment and allowing the disease to recur.”40 Invoking the 1905 US Supreme Court decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts that upheld compulsory immunization statutes, Baker asserted that the state had the authority to limit individual liberty to protect the public’s health and the rights of others. In a reprise of arguments made a decade earlier when helmet laws were under constitutional attack, Baker emphasized the social burden created by motorcycle accidents and fatalities.41

In 1981, the American Journal of Public Health published a counterpoint to Baker’s editorial, which was unusual in that it came from a public health official. Richard Perkins of New Mexico’s Health and Environment Department attacked the argument that the motorcyclist was reducing the freedom of others by not wearing a helmet as “so ridiculous as to be ammunition for the anti-helmet law forces.”42 Noting that there were no helmet laws for rodeo contestants and rock climbers, he argued that laws should consider not only safety but also “such intangible consequences as potential loss of opportunity for individual fulfillment and loss of social vitality.”42

Baker and Stephen Teret offered a rebuttal to Perkins and stated that his argument “implies that if policy is not applied at the outer limits of a continuum of circumstances, it would be unreasonable to apply that policy at any point along the continuum.”43 They defended their reliance on Jacobson v. Massachusetts by pointing out that the decision has been used as a precedent for decisions that cover “manifold” restraints on liberty for the common good beyond the scope of contagious disease.43

During the next decade, evidence of the human and social costs of repeal continued to mount. Medical costs among helmetless riders increased 200% compared with helmeted riders, and in some states, helmetless riders were more likely to be uninsured.44 The April 1987 issue of Texas Medicine published an editorial entitled “How many deaths will it take?”45 The editorial exemplified the growing frustration among physicians, epidemiologists, and public health officials with legislatures that failed to act on evidence that showed helmet law repeals increased fatalities and serious injuries. “I invite our legislators and those opposed to helmet laws to spend a few nights in our busy emergency rooms,”45 wrote the author, who was the chief of neurosurgery at Ben Taub General Hospital in Houston. “Let them talk to a few devastated mothers and fathers of sons with severe head injuries—many of whom will needlessly die or remain severely disabled.”45 Posing a challenge to the antipaternalism that had inspired the repeal of laws, he contended, “[a] civilized society makes laws not only to protect a person from his fellowman, but also sometimes from himself as well.”45

Other studies adopted a more narrowly economic perspective on the impact of helmet law repeals. In a 1983 article, researchers sponsored by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety used mathematical models to estimate the number of excess deaths—those that would not have occurred had the motorcyclist been wearing a helmet—in the 28 states that had repealed their helmet laws by 1980. They then conducted an economic analysis of the costs to society as a result of these deaths. This cost calculation incorporated direct costs (emergency services, hospital and medical expenses, legal and funeral expenses, and insurance and government administrative costs) and indirect costs (the value of the lost earnings and services due to the death of the person). The researchers found that the costs totaled at least $176.6 million.46

In Europe, meanwhile, where helmet laws were being enacted for the first time, studies were showing an opposite effect. In Italy, where a compulsory motorcycle helmet law went into effect in 1986, a group of researchers compared the accidents in 1 district (Cagliari) during the 5 months before and the 5 months after the law’s enactment. They found a 30% reduction in motorcycle accidents and an overall reduction in head injuries and deaths.47

HELMET LAWS IN THE CONGRESS ONCE AGAIN

In May 1989, against a backdrop of 34 states’ adoption of mandatory automobile seat belt laws, Senator John Chafee (R-RI) held a news conference to announce he was introducing a bill—the National Highway Fatality and Injury Reduction Act of 1989—that would empower the US Department of Transportation to withhold up to 10% of federal highway aid from any state that did not require motorcyclists to wear helmets and front-seat automobile passengers to wear seat belts.48 The conference was strategically held during a meeting of the American Trauma Society.49

A hearing on the bill that was held by the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works in October 1989 provided yet one more opportunity to engage (in a federal forum) the argument about the potential benefits that would result from the enactment of mandatory helmet laws and the deep philosophical issues such laws raised.50 As had others before him, Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) sought to compare the imposition of helmet requirements with the public health justification for compulsory immunization.51 Senator James Jeffords (R-VT) responded with an invocation of the antipaternalistic argument so resonant in American political culture.

Would you urge us then, at the Federal level, to mandate diets and to investigate homes as far as diets are concerned? We would save a lot more money if we had good nutrition in this country. Do you think that is a proper role of the government? . . . I think there is a vast difference in vaccination, where you are subjecting others to a health problem, . . . where you are trying to protect the individual health of someone who is in a sense endangering himself and not the public. I grant the arguments are there on cost, but the arguments are there on cost in nutrition, as well. I have a hard time, philosophically, accepting that the role of the government is to tell us how to lead our lives. Why don’t we have motorcycle riders wear armored suits? Where do you draw the line? It is my understanding that the largest percentage of injuries are not by head, but are injuries to the chest and the abdominal areas and things like that. So where do you stop?52

Senator Jeffords’ comments were echoed by Robert Ford, chairman of Massachusetts Freedom First, an auto group that had led a successful campaign to repeal the state’s seat belt law. Ford did not quibble with statistics that showed seat belts make people safer. Instead, he argued that the issue was about fundamental individual liberty.

We do not want to be told how to behave in matters of personal safety. We do not want to be forced to wear seat belts or helmets because others think that it is good for us. We do not want to be forced to eat certain diets because some think that it too may be good for us, reduce deaths and medical costs, and make us more productive citizens. We do not want to be forced to give up certain pastimes simply because some may feel they entail any amount of unnecessary risk.53

Instead of confronting the moral arguments made by opponents of helmet laws, proponents of such measures sought once again to marshal the compelling force of evidence. In 1991, at the request of Senator Moynihan, the General Accounting Office issued a comprehensive report that documented the toll. The report reviewed 46 studies and found that they overwhelmingly showed helmet use rose and fatalities and serious injuries plummeted after enactment of mandatory universal helmet laws.54

Despite the fierce opposition of motorcycle groups, Senator Chafee ultimately succeeded in getting the motorcycle helmet law and seat belt law provisions added to a major highway funding bill that was passed in December 1991. Under the law—which was far less punitive than what Senator Chafee had originally proposed—states that failed to pass helmet laws would have 3% of their highway funds withheld.55

REENACTMENT AND REPEAL

In 1991, the momentum seemed to be turning in favor of state motorcycle helmet laws. For the first time in its history, California enacted a universal mandatory helmet law, which took effect on January 1, 199256; however, this brief moment of public health optimism was short-lived. In 1995, after the “Gingrich Revolution,” in which conservative Republicans took control of Congress, the national motorcycle lobby succeeded in getting the federal 3% highway safety fund penalties repealed.57 In 1997, after pressure from state-level motorcycle activists, Arkansas and Texas repealed their universal helmet laws and instead required helmets only for riders aged younger than 21 years. These repeals were followed by similar actions in Kentucky (1998), Louisiana (1999), Florida (2000), and Pennsylvania (2003). In a move that gave credence to the well-worn claim about the social costs of private choice, several of the new laws required riders to have $10 000 of medical insurance coverage policy before they could ride helmetless.

This new round of repeals of motorcycle helmet laws produced a predictable series of studies, with all too predictable results: in Arkansas and Texas, helmet use decreased significantly, head injuries increased, and fatalities rose by 21% and 31%, respectively.58 In 2003, a study of Louisiana and Kentucky fatalities found that after repeal of helmet laws, there was a 50% increase in fatalities in Kentucky and a 100% increase in fatalities in Louisiana. In 2005, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety released a study that showed Florida’s helmet law repeal had led to a 25% increase in fatalities in 2001 and 2002 compared with the 2 years before the repeal.59

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past 30 years, helmet law advocates have gathered a mountain of evidence to support their claims that helmet laws reduce motorcycle accident fatalities and severe injuries. Thanks to the rounds of helmet law repeals, advocates have been able to conclusively prove the converse as well: helmet law repeals increase fatalities and the severity of injuries. But the antihelmet law activists have had 3 decades of experience fighting helmet laws, and they have learned that their strategy of tirelessly lobbying state legislators can work. As one activist wrote, “I learned that the world is run by those who bother to show up to run it.”60 More important, they have learned a lesson about how persuasive unadorned appeals to libertarian values can be.

This history of motorcycle helmet laws in the United States illustrates the profound impact of individualism on American culture and the manner in which this ideological perspective can have a crippling impact on the practice of public health. Although the opponents of motorcycle helmet laws seek to shape evidence to buttress their claims, abundant evidence makes it clear—and has done so for almost 3 decades—that in the absence of mandatory motorcycle helmet laws, preventable deaths and great suffering will continue to occur. The NHTSA estimated that 10 838 additional lives could have been saved between 1984 and 2004 had all riders and passengers worn helmets.61 The success of those who oppose such statutes shows the limits of evidence in shaping policy when strongly held ideological commitments are at stake.

Early on in the battles over helmet laws, advocates for mandatory measures placed great stress on the social costs of riding helmetless. The courts, too, have often adopted claims about such costs as they upheld the constitutionality of statutes that impose helmet requirements. Whatever the merit of such a perspective, it clearly involved a transparent attempt to mask the extent to which concerns for the welfare of cyclists themselves were the central motivation for helmet laws. The inability to successfully and consistently defend these measures for what they were—acts of public health paternalism—was an all but fatal limitation.

The recent trend toward motorcycle helmet laws that cover minors, however, shows that legislators and some antihelmet law forces have accepted a role for paternalism in this debate. The need for a law that governs minors shows a tacit acknowledgment that (1) motorcycle helmets reduce deaths and injuries and (2) the state has a role in protecting vulnerable members of society from misjudgments about motorcycle safety. Ironically, then, it is the states within which the motorcycle lobby has been most effective that have most directly engaged paternalist concerns.

The challenge for public health is to expand on this base of justified paternalism and to forthrightly argue in the legislative arena that adults and adolescents need to be protected from their poor judgments about motorcycle helmet use. In doing so, public health officials might well point to the fact that paternalistic protective legislation is part of the warp and woof of public health practice in America. Certainly, a host of legislation—from seat belt laws to increasingly restrictive tobacco measures—is aimed at protecting the people from self-imposed injuries and avoidable harm.

With the latest round of helmet law repeals, motorcycle helmet use has dropped precipitately to 58% nationwide, and fatalities have risen.62 Need anything more be said to show that motorcyclists have not been able to make sound safety decisions on their own and that mandatory helmet laws are needed to ensure their own safety?

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the faculty and students of the Center for History and Ethics of Public Health at the Mailman School of Public Health and colleagues in the Department of Sociomedical Sciences who reviewed this article.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

Peer Reviewed

Contributors R. Bayer originated the study. M.M. Jones conducted historical research. The authors co-wrote the text.

Endnotes

- 1.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), Traffic Safety Facts Laws, Motorcycle Helmet Use Laws, January 2006, available at http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/staticfiles/DOT/NHTSA/Rulemaking/Articles/Associated%20Files/03%20Motorcycle%20Helmet%20Use.pdf, accessed November 22, 2006.

- 2.“The Effect of Helmet Law Repeal on Motorcycle Fatalities,” NHTSA Technical Report, DOT HS 065, December 1986, p. 2; D.F. Preusser, J. H. Hedlund, and R. G. Ulmer, “Evaluation of Motorcycle Helmet Law Repeal In Arkansas and Texas,” NHTSA, September 2000, pp. 43–48. The 47 state statutes marked the high water point for mandatory helmet legislation, reached between September 1, 1975, and May 1, 1976. They do not include Utah, which in the 1970s required helmets only on roads with a 35 mph or higher speed limit.

- 3.States with Primary Safety Belt Laws in 2004, States with Secondary Safety Belts, NHTSA website, available at http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/outreach/state_laws-belts05/safetylaws-states.htm, accessed October 20, 2006; Fatality Reduction by Air Bags: Analyses of Accident Data Through Early 1996, NHTSA Report No. DOT HS 808 470, August 1996, available at http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/cars/rules/regrev/evaluate/808470.html, accessed October 20, 2006.

- 4.“Thailand: Effect of a Mandatory Helmet Law on Fatalities,” World Health Organization Helmet Initiative Headlines Newsletter, Summer 2005, available at http://www.whohelmets.org/headlines/05-summer-thailandlaws.htm, accessed October 20, 2006. The article reports a study showing that Thailand’s helmet law has failed to reduce fatalities by motorcycle accidents partly because helmet quality is unregulated and proper helmet usage is not enforced.

- 5.“Worldwide Motorcycle Safety Helmet Laws,” UNESC Working Party on Road Traffic Safety; TRANS/WP. 1.80/Rev 28 January 2003, Table 9, available at http://www.whohelmets.org/helmetlaws.htm, accessed November 22, 2006.

- 6.“Obituary, Hugh William Bell Cairns,” Lancet, July 26, 1952, p. 202. [PubMed]

- 7.Maartens Nicholas F., Andrew D. Wills, Christopher B. T. Adams, “Lawrence of Arabia, Sir Hugh Cairns, and the Origin of Motorcycle Helmets,” Neurosurgery, 50 (2002):177. R. F. Hugh Cairns, “Head Injuries in Motorcyclists: The Importance of the Crash Helmet,” British Medical Journal 2:465–483, 1941; Cairns, “Crash helmets. Br Med J 2:322–324, 1946; Cairns, AHS Holbourn, “Head injuries in motorcyclists, with special reference to crash helmets,” British Medical Journal 1 (1943):592–598. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker Edward B., “Helmet Development and Standards,” in N. Yoganandan, et al., eds., Frontiers in Head and Neck Trauma: Clinical and Biomedical, IOS Press, 1998, p. 3.

- 9.The Art of the Motorcycle, New York: Guggenheim Museum, 1998, pp. 205–209, 250; Ross Fuglsang, Motorcycle Menace: Media Genres and the Construction of a Deviant Culture, unpublished dissertation, University of Iowa, 1997, Chapter 2.

- 10.An Inside Look at Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (Boulder, Colo: Paladin Press, 1992), p. 3, cited in Fuglsang, Chapter 2.

- 11.Surface Transportation Part 1, Hearing of the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation, July 9–31, 1975, H 641–5, p. 368.

- 12.Rutstein David D., “At the Turn of the Next Century,” in John H. Knowles, ed., Hospitals, Doctors, and the Public Interest, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1965, p. 311.

- 13.Lalonde Marc, A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians; A Working Document, Ottawa, Canada. Department of National Health and Welfare, 1974; Institute of Medicine (US), Healthy People: The Surgeon General’s Report On Health Promotion And Disease Prevention, DHEW (PHS) publication; no. 79-55071A, US Government Printing Office, 1979; John H. Knowles, “The responsibility of the individual,” Daedalus, 1977 Winter; 57–80.

- 14.“Compliance with the 1992 California Motorcycle Helmet Use Law,” American Journal of Public Health, 85 (1995): 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pullen Emma E., “State Faces Loss of U.S. Road Funds,” Los Angeles Times, August 5, 1975, p. B3.

- 16.Quinn James, “Cyclists Take Aim at Proposed Helmet Law,” Los Angeles Times, September 16, 1973, p. GB1; “Motorcycle Helmet Proposal Withdrawn By Councilman,” Los Angeles Times, September 23, 1973.

- 17.State appeals or supreme courts have found mandatory motorcycle helmet laws to be a constitutional exercise of police power in: Love v. Bell, 171 Colo. 27, 465 P. 2d 118 (Colo. 1970); Hawaii v. Lee, 51 Haw. 516, 465 P. 2d 573 (Hawaii 1970); Missouri v. Cushman, 451 S.W. 2d 17 (Mo. 1970); North Carolina v. Anderson, 275 N.C. 168, 166 S.E. 2d 49 (1969); New Jersey v. Krammes, 105 N.J. Super. 345, 252 A. 2d 223 (1969); North Dakota v. Odegaard, 165 N.W. 2d 677 (N.D. 1969); Ohio v. Craig, 19 Ohio App. 2d 29, 249 N.E. 2d 75 (1969); Oregon v. Fetterly, 254 Ore. 47, 456 P. 2d 996 (Ore. 1969); Arutanoff v. Metro Government of Nashville and Davidson County, 223 Tenn. 535, 448 S.W. 2d 408 (Tenn. 1969); Ex parte Smith, 441 S.W. 2d 544 (Tex. Cr. App. 1969); Vermont v. Solomon, 128 Vt. 197, 260 A. 2d 377 (Vt. 1969); Washington v. Laitinen, 77 Wash. 2d 130, 459 P. 2d 789 (Wash. 1969); Bisenius v. Karns, 42 Wis. 2d 42, 165 N.W. 2d 377 (1969); Overheard v. City of New Orleans, 253 La. 285, 217 So. 2d 400 (1969); Com. v. Howie, 354 Mass. 769, 238 N.E. 2d 373 (Mass. 1968). State appeals or high courts have found mandatory motorcycle helmet laws to be unconstitutional in People v. Fries, 42 Ill. 2d 446, 250 N.E. 2d 149 (1969) and American Motorcycle Association v. Department of State Police, Docket No. 4,445, Court of Appeals of Michigan, 11 Mich. App. 351; 158 N.W. 2d 72.

- 18.Simon v. Sargent, 346 F. Supp. 277; Appeal, 409 U.S. 1020; 93 S. Ct. 463 (1972). In Bogue v. Faircloth, 316 F. Supp. 486 (1970) brought in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, the appellants, also motorcyclists who had been arrested under a state’s helmet law, alleged a violation of their federal civil rights.

- 19.People v. Fries, 42 Ill. 2d at 450.

- 20.American Motorcycle Association v. Department of State Police, supra.

- 21.American Motorcycle Association v. Department of State Police, supra, at 357.

- 22.Simon v. Sargent, supra, at 278.

- 23.Mill, John Stuart, On Liberty, Chapter 1, Introductory, London: Longman, Roberts and Green, 1869; New York: Bartleby.Com, 1999, available at http://www.bartleby.com/130/index.html. Accessed December 17, 2006.

- 24.Simon v. Sargent, supra, at 279.

- 25.Bogue v. Faircloth, 316 F. Supp. 486 (1970) at 489.

- 26.“The History of the AMA,” American Motorcylist Association, available at http://www.amadirectlink.com/whatis/history.asp. Accessed December 17, 2006.

- 27.Fuglsang, Chapter 7, available at http://webs.morningside.edu/masscomm/DrRoss/Research.html. Accessed December 17, 2006.

- 28.“Street Legal Chopper, Circa 1973?” Easyriders, October 1971, available at http://www.abateonline.org/ABATE.aspx?PID-240. Accessed December 17, 2006. Also see Fuglsang, Motorcycle Menace, Chapter 7.

- 29.“ABATE Membership in 44 States Have Started Working Toward Our Freedom of the Road,” Easyriders, February 1972, available at: http://www.bikerrogue.com/articles/biker_rights/history_of_abate/history_of_abate.htm. Accessed October 20, 2006. Also see Fuglsang, Motorcycle Menace, Chapter 7.

- 30.Modified Motorcycle Organization of California, available at http://www.mmaweb.org/index.html. Accessed November 22, 2006. Marcida Dodson, “Bikers Find No Vroom to Be Alone,” Los Angeles Times, May 21, 1981, p. OC-A1. Surface Transportation Part 1, Hearing of the House Committee on Public Works and Transportation, July 9–31, 1975, H 641–5, p. 454.

- 31.For more on the more activist policymaking role of Congress during the Ford administration, see Cronin Thomas E., “A Resurgent Congress and the Imperial Presidency,” Political Science Quarterly, 95 (1980): 209–237. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surface Transportation Part 1, p. 401.

- 33.Davey testimony, Surface Transportation Part 1, p. 373.

- 34.ABATE of Washington, available at http://www.abate-wa.org/aboutus.htm. Accessed December 17, 2006.

- 35.Surface Transportation, Part I, pp. 387–390, p. 456–460.

- 36.Young David, “State to Present Case on Cycle Helmet Ruling,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1975, p. B10; “Senate Votes Reprieve for States Lacking Motorcycle Helmet Law,” Los Angeles Times, December 13, 1975, p. B10; “Ford Signs Extension of Highway Aid,” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1976, p. B14. Dennis V Cookro, MD, MPH, “Motorcycle Safety: An Epidemiologic View,” Arizona Medicine, August 1979, pp. 605.

- 37.“Law eased, cycle deaths soar,” Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1978, p. W_A4.

- 38.Peterson, “Motorcyclists, Helmeted or Not, Fight Restriction,” New York Times, July 31, 1978, p. NJ11, citing Claybrook.

- 39.“Highway Panel Seeks Required Helmet Use by Motorcycle Riders,” Wall Street Journal, January 12, 1979, p. 8; Peterson, July 31, 1978, p. NJ11; Ernest Holsendolph, “U.S. Safety Chief Urges Helmets to Cut Deaths of Motorcyclists,” New York Times, January 12, 1979, p. A12; “Evaluation of Motorcycle Helmet Law Repeal in Arkansas and Texas,” NHTSA, pp. 45–48.

- 40.“The Motorcyclist as Gladiator,” North Carolina Medical Journal, (1979): 362–364. [PubMed]

- 41.Susan P. Baker, MPH, “On Lobbies, Liberty, and the Public Good,” American Journal of Public Health, 70 (1980): 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perkins Richard J., “Perspective on the Public Good,” American Journal of Public Health, 71 (1981): 294–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker and Stephen P. Teret, JD, MPH, “Freedom and Protection: A Balancing of Interests,” American Journal of Public Health, 71 (1981): 295–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watson Geoffrey, Paul Zador, and Alan Wilks, “The Repeal of Helmet Use Laws and Increased Motorcyclist Mortality in the United States, 1975–1978,” American Journal of Public Health, 70 (1980): 579–584 (nearly 40 percent increase in fatal motorcycle injuries in states that repealed helmet laws, 1975–1978); Norman E. McSwain, Jr, and Elaine Petrucelli, “Medical Consequences of Motorcycle Helmet Nonusage,” Journal of Trauma, 19 (1987): 233–236 (Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, South Dakota analyzed; significant increase in injury and death and up to 200% increase in medical costs); Donald J. Scholten, John L. Glober, “Increased Mortality Following Repeal of Mandatory Motorcycle Helmet Law,” Indiana Medicine, (1984) 252–255 (36.9 percent increase in death rate); Thomas C. Chenier and Leonard Evans, “Motorcyclist Fatalities and the Repeal of Mandatory Helmet Wearing Laws,” Accident Analysis and Prevention, 19 (1987): 133–139; Linda E. Lloyd, Mary Lauderdale, Thomas G. Betz, “Motorcycle Deaths and Injuries in Texas: Helmets Make a Difference,” Texas Medicine, 83 (1987): 30–35 (more than 1,000 excess deaths from helmet nonusage in Texas; nonhelmeted riders more likely to be uninsured); Leonard Evans and Michael C. Frick, “Helmet Effectiveness in Preventing Motorcycle Driver and Passenger Fatalities,” Accident Analysis and Prevention, 20 (1988): 447–458 (NHTSA Fatal Accident Reporting System analysis found helmets [28% ±8%] effective in preventing fatalities).7377433 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narayan Raj K, “How Many Deaths Will It Take?” Texas Medicine, 83 (1987): 5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hartunian Nelson S., Charles N. Smart, Thomas R. Willemain, Paul L. Zador, “The Economics of Safety Deregulation: Lives and Dollars Lost due to Repeal of Motorcycle Helmet Laws,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 8 (1983): 76–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nurchi G. C., P. Golino, F. Floris. et al., “Effect of the law on compulsory helmets in the incidence of head injuries among motorcyclists,” Journal of Neurosurgical Science, 31 (1987): 141–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Highway Fatality and Injury Reduction Act of 1989, Hearing before the Subcommittee on Water Resources, Transportation, and Infrastructure of the Committee on Environment and Public Works, United States Senate, 101st Congress, First Session, on S. 1007, A Bill to Amend Title 23, United States Code, Regarding the Reduction in Apportionment for Federal-Aid Highway Funds to Certain States, and for Other Purposes, October 17, 1989, p. 8; Laszlo Dosa, “Worried About Dying? Worry About Accidents,” The Washington Post, June 13, 1989, p. Z5; Robert Greene, “Cyclists, Officials Oppose Bill Tying Road Aid to Helmet, Belt Laws,” Associated Press, October 17, 1989, Tuesday AM Cycle.

- 49.Dosa, “Worried About Dying?” p. Z5; Hearings, pp. 14, 58.

- 50.1989 Hearing, pp. 6–7.

- 51.1989 Hearing, p. 18.

- 52.1989 Hearing, pp. 18–19.

- 53.1989 Hearing, pp. 70–71.

- 54.“Highway Safety Motorcycle Helmet Laws Save Lives and Reduce Costs to Society,” GAO Report RCED-91-170, July 29, 1991, pp. 2–5.

- 55.Curtin Wayne T., MRF Vice President for Government Relations, “Focus + Unity = Repeal of Federal Helmet Law,” Motorcycle Riders Foundation White Paper, September 1996, available at http://www.mrf.org/pdf/whitepapers/volume4-1996/repealoffederalhelmetla.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2006.

- 56.Bishop Katherine, “California’s Helmetless Ride is Over, but Not the Debate,” New York Times, January 1, 1992, p. 8.

- 57.Hess David, Knight-Ridder Tribune News, “Leverage on budget goes to Republicans; Clinton’s concessions frustrate Dems,” The Houston Chronicle, December 2, 1995, p. 19.

- 58.Preusser, et al., “Evaluation of Motorcycle Helmet Law Repeal in Arkansas and Texas.”

- 59.“Deaths Up Since Florida Helmet Law Repealed,” Associated Press, August 10, 2005, available at http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/1341966. Accessed October 20, 2006.

- 60.Ray Ken, Legislative Director, BikePAC of Oregon, “The Giant Sucking Sound,” Motorcycle Riders Foundation, September 1998 White Papers, available at http://www.mrf.org/pdf/whitepapers/volume5-1998/thegiantsuckingsound.pdf. Accessed October 20, 2006.

- 61.NHTSA, “Traffic Safety Facts Laws, Motorcycle Helmet Use Laws,” January 2006.

- 62.Ibid.