Trigeminal neuralgia is a severe unilateral paroxysmal facial pain, often described by patients as the “the world's worst pain.”

Summary points

Trigeminal neuralgia is a rare but characteristic pain syndrome

Most cases are still referred to as idiopathic, although many are associated with vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve

A minority of cases are symptomatic of multiple sclerosis or nerve compression by tumour

The condition is variable and patients may have just one episode

Most patients respond well to drugs; carbamazepine is usually the first line treatment

If drug treatment fails or is not tolerated, surgical treatments are available

Ablative surgical treatments are associated with facial sensory loss, almost no risk of severe complications or death, and a high rate of pain recurrence; microvascular decompression has a risk of severe complications or death, albeit very low, and a lower relapse rate

How common is trigeminal neuralgia?

The diagnosis is made by general practitioners in 27 per 100 000 people each year1 in the United Kingdom. However, previous population based studies with a strict case definition estimated the rate to be 4-13 per 100 000 people each year.2 3 Almost twice as many women are affected as men.3 The incidence gradually increases with age and is rare below 40.

If it is uncommon why do I need to read this?

The condition causes severe pain, which responds poorly to analgesics, but when recognised it can be treated. The pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia is becoming clearer. A wide range of medical and surgical treatments has been developed and introduced, usually without randomised clinical trials. As a result, uncertainty remains about how best to use the available treatments.

Data sources and selection criteria

We searched Medline, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), and Cochrane databases using the terms “trigeminal neuralgia”, “tic douloureux”, and “facial pain”. All related articles from the NICE and Cochrane databases were obtained. We searched Medline citation lists by title and abstract for relevant publications, including randomised control trials and review articles. The citation lists of these articles were hand searched for further relevant articles.

How is the diagnosis made?

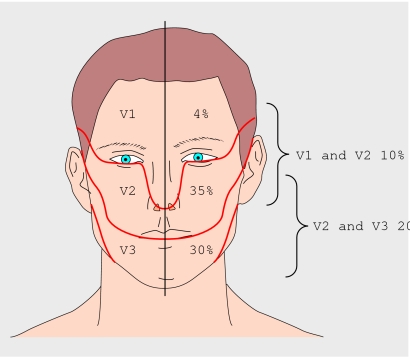

Trigeminal neuralgia is a clinical diagnosis. The key feature is a sudden and severe lancinating pain, which usually lasts from a few seconds to two minutes, within the trigeminal nerve distribution, typically the maxillary or mandibular branches (fig 1). The pain is often evoked by trivial stimulation of appropriately named “trigger zones.” Occasionally the pain is so severe that it prevents eating or drinking. The nerves affected are usually stereotyped for a particular patient and lie within the sensory distribution of the trigeminal nerve. Box 1 lists the diagnostic criteria for the classic form of the disease.

Fig 1 Distribution of trigeminal neuralgia.3 In another 1% of patients it also affects all three divisions and rarely it can be bilateral (though paroxysms are not synchronous)

Box 1 Diagnostic criteria for classic trigeminal neuralgia4

Paroxysmal attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to two minutes that affect one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve

Pain has at least one of the following characteristics

intense, sharp, superficial, or stabbing

precipitated from trigger areas or by trigger factors

Attacks are similar in individual patients

No neurological deficit is clinically evident

Not attributed to another disorder

In many cases the pain does not fit these criteria exactly because of a persistent ache between paroxysms or mild sensory loss. Such disease has been labelled as “atypical”5 or “mixed” trigeminal neuralgia.6 Patients with atypical disease are more likely to have symptomatic rather than idiopathic disease, and they are often more refractory to treatment6 than those with classic trigeminal neuralgia.7 Atypical trigeminal neuralgia should not be confused with atypical facial pain (table 1).

Table 1.

Common conditions that are usually easy to distinguish from trigeminal neuralgia

| Diagnosis | Important features |

|---|---|

| Dental infection or cracked tooth | Well localised to tooth; local swelling and erythema; appropriate findings on dental examination |

| Temporomandibular joint pain | Often bilateral and may radiate around ear and to neck and temples; jaw opening may be limited and can produce an audible click |

| Persistent idiopathic facial pain (previously “atypical facial pain”)4 | Often bilateral and may extend out of trigeminal territory; pain often continuous, mild to moderate in severity, and aching or throbbing in character |

| Migraine | Often preceded by aura; severe unilateral headache often associated with nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and neck stiffness |

| Temporal arteritis | Common in elderly people; temporal pain should be constant and often associated with jaw claudication, fever, and weight loss; temporal arteries may be firm, tender, and non-pulsatile on examination |

What causes trigeminal neuralgia?

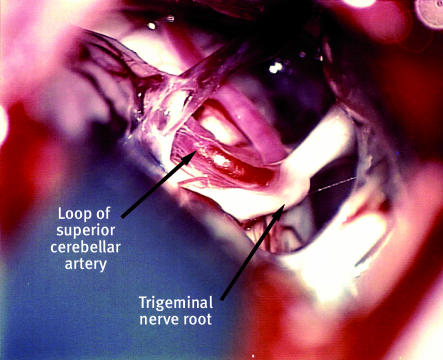

Increasing evidence (box 2) suggests that 80-90% of cases that are technically still classified as idiopathic are caused by compression of the trigeminal nerve (fig 2) close to its exit from the brainstem by an aberrant loop of artery or vein.5 10

Fig 2 Compression of the trigeminal nerve root by an aberrant loop of the superior cerebellar artery. Photograph provided by Hugh B Coakham

Box 2 Evidence that vascular compression commonly causes trigeminal neuralgia5 10

An aberrant loop of artery, or less commonly vein, is found to be compressing the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve in 80-90% of patients at surgery

The trigeminal nerve is demyelinated next to the compressing vessel

Eliminating the compression by surgery provides long term relief in most patients

Intraoperative assessments report immediate improvement in trigeminal conduction on decompression

Sensory function recovers after decompression

Other causes, such as compression by tumours or the demyelinating plaques of multiple sclerosis, produce similar lesions of the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve

Importantly, compression is of the root entry zone, where axons are coated with central nervous system myelin, rather than peripheral nerve myelin. Similarly, vascular compression of the facial and glossopharyngeal nerves is thought to be responsible for most cases of hemifacial spasm and glosspharyngeal neuralgia, respectively.10 w1

Less than 10% of patients will have symptomatic disease associated with an identifiable cause other than a vascular compressive lesion—usually a benign tumour or cyst—10 11 or multiple sclerosis. About 1-5% of patients with multiple sclerosis develop trigeminal neuralgia.5

Why is trigeminal neuralgia paroxysmal?

The paroxysmal pain of trigeminal neuralgia is distinct from many other neuropathic pains, which often have a constant, burning quality. Why does constant compression or damage of the trigeminal nerve produce paroxysmal rather than constant pain? Although not confirmed the “ignition hypothesis”w2 offers a plausible explanation.

Compression of the root entry zone leads to demyelination and axonal damage10 w3 w4

Damaged axons become electrically hyperexcitable, exude neurotransmitters and potassium into the interstitial space, and, crucially, can repetitively fire at high frequency (resonance)w2—a rare property in healthy sensory axons unless artificially stimulated by an electric shock

Demyelination leaves bare axons, often subserving different sensory modalities such as light touch and pain, in contact with one another; this allows ephaptic transmission directly between them

A “spark”—often from light touch or cold in a trigger zone—“ignites” a self fuelling “inferno” of electrical discharge dependent upon all the above mechanisms. This rapidly burns itself out as axons become hyperpolarised, leading to the sudden and merciful cessation in pain and characteristic refractory period of a minute or so during which further pain cannot be triggered.w2

Most facial pain is not trigeminal neuralgia

Other causes of facial pain are much more common than trigeminal neuralgia. This can often lead to delay in diagnosis as patients see dentists and doctors who consider more common alternatives first.

Common causes of facial pain are usually straightforward to eliminate clinically or after dental examination (table 1); rarer alternatives may evade consideration (table 2). Many alternatives affect the forehead only, which is rare for trigeminal neuralgia, so trigeminal neuralgia affecting the forehead should be diagnosed with caution. Although tearing and other autonomic features can occur in trigeminal neuralgia, these features combined with forehead pain should prompt consideration of the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (for example, cluster headache).4

Table 2.

Rare conditions that may be difficult to distinguish from trigeminal neuralgia (which has been included for comparison)

| Diagnosis | Important features | Typical duration of attack | Range of duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trigeminal neuralgia | See text; trigeminal neuralgia rarely affects the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, so forehead pain is rarely trigeminal neuralgia | 4 seconds | 2-120 seconds |

| Primary stabbing headache | Also known as “ice pick headache;” short stabs of pain in temporal region usually lasting a second or less5 | 1 second | 1-10 seconds |

| Short lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjuctival injection and tearing* | Brief attacks of severe unilateral periorbital and forehead pain associated with ipsilateral conjuctival injection and lacrimation | 40 seconds | 5-250 seconds |

| Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania* | Stabbing, throbbing, or boring pain that affects the eye and forehead; may have 5-10 attacks daily | 5-15 seconds | 2-46 seconds |

| Cluster headache* | Sever unilateral forehead pain, often associated with hyperactivity during the attack, ipsilateral conjunctival injection, and Horner's syndrome | 40 minutes | 8-238 minutes |

| Trigeminal neuropathy | Continuous pain with sharp exacerbations; pronounced sensory deficit | Continuous | |

| Post-herpetic neuralgia | Seen after shingles (usually more than 3 months after); often affects forehead; continuous burning pain with sharp exacerbations | Continuous | |

| Occipital neuralgia | Pain similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia but affects back of head | Seconds | Not available |

| Glossopharyngeal neuralgia | Pain very similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia but affects posterior third of the tongue, tonsils, and pharynx | Seconds | Not available |

*Grouped together as trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias.

What investigations are needed?

Investigations are done to:

Clarify the differential diagnosis; for example, by taking dental x rays

Investigate whether there is an identifiable cause of the disease, particularly with a view to surgical cure. This is best done using magnetic resonance imaging.

As 5-10%11 of cases are caused by tumours, multiple sclerosis, abnormalities of the skull base, or arteriovenous malformations the threshold for magnetic resonance imaging should be low. A brain scan should be obtained in younger patients; those with atypical clinical features, including sensory loss or a dull burning pain between paroxysms; and patients who do not respond to initial medical therapy.

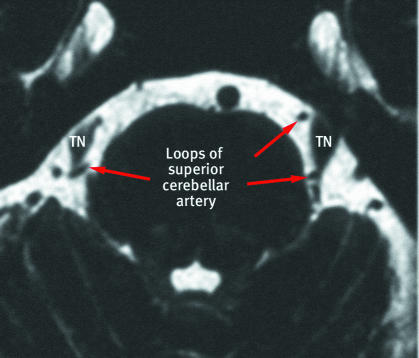

With recent improvements in magnetic resonance imaging techniques (fig 3), vascular compression is being demonstrated radiologically in increasing numbers of patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Studies where radiologists are blinded to the side of the pain have produced good results in terms of predicting subsequent surgical findings and response to surgery.12 w6 Postmortem studies have found vessels in contact with the trigeminal nerve in 3-12%5 of asymptomatic patients. Thus, currently these imaging techniques should be used to explore surgical treatment options in clinically diagnosed trigeminal neuralgia, rather than in making a diagnosis.

Fig 3 Axial constructive interference in steady state magnetic resonance imaging through the brainstem of patient with bilateral compression of trigeminal nerve (TN) roots by aberrant loops of the superior cerebellar arteries

Which magnetic resonance imaging techniques are best?

The magnetic resonance imaging techniques used to detect neurovascular compression are variable and continually improving. Patel et al from our centre reported 90.5% sensitivity and 100% specificity when using 1.5T magnetic resonance imaging and contrast enhanced magnetic resonance angiography to detect vascular compression of the trigeminal root.12 The imaging protocol used to obtain these figures includes a fast spin echo T2 weighted axial sequence of the whole brain with parameters of 2515/120/2 (TR/TE/excitations), a slice thickness of 6 mm with an intersection gap of 0.6 mm, a matrix size of 512_512, and a field of view of 23 cm. This is followed by thin slice, high resolution (3 mm thick with 0.3 mm intersection gap; 512_512 matrix) fast spin echo T2 weighted scans performed in the axial and coronal planes through the posterior fossa. The first procedure uses parameters of 2873/120/4 and a field of view of 20 cm, and the second uses 1496/120/4 with a field of view of 19 cm. Conventional magnetic resonance imaging is generally poor at identifying neurovascular relations. We assess neurovascular compression in our neurosurgical centre by means of a gadolinium enhanced (using intravenous 0.1 mmol/kg Magnevist) three dimensional magnetic resonance angiography fast field echo sequence obtained in the axial plane. The parameters are 17/6/2, flip angle 24_, matrix size 256_512, field of view 11 cm, slice thickness 0.6 mm, and no gap.

What is the natural course of trigeminal neuralgia?

Because the severity of the pain demands intervention, no studies of the natural course of the disease are available. One study collected information from linked primary and secondary care records over a 40 year period.3 They found that 29% of patients had only one episode of pain, 19% had two, 24% had three, and 28% had four to 11. Each episode lasted from one day to four years (median 49 days). After the first episode 65% of patients had a second within five years, though in 23% the gap was more than 10 years. Similar ranges of delay were seen from the second to the third event. This highlights the wide spectrum from single to frequent episodes, with each episode being of variable duration.

Most of the case series reporting surgical and other treatments for trigeminal neuralgia are from tertiary care centres and therefore represent the most severely affected patients.

What are the best medical treatments?

Drug treatments for trigeminal neuralgia have been the subject of several Cochrane systematic reviews.13 14 15 These reviews bring together the small number of trials available in a condition that poses difficulties for study design (box 3). Perhaps unsurprisingly the evidence is mostly weak.

Box 3 Problems associated with studies of trigeminal neuralgia

Related to the condition

Condition rare

Condition variable, with spontaneous remission and relapse

Condition has uncertain natural history

Condition is a clinically defined syndrome with no gold standard diagnosis

The pain is so severe that placebo control studies are considered unethical

Related to the study

Diagnostic criteria variably interpreted and applied

Lack of standardised outcome measures

Quality of life rarely measured

Open unblinded non-randomised studies predominate

Based on case series, usually from tertiary referral centres

Related to treatment

Carbamazepine, the standard treatment, has a long half life and induces liver enzymes, making crossover studies difficult

Most drugs used are out of patent, which limits funding opportunities

Related to surgery16

Difficult to achieve blinding or use sham operations

Different types of risks are being compared with different procedures (see text)

Available evidence shows that carbamazepine is the drug of choice (table 3).15 17 Many patients develop adverse effects, however, though most can continue taking the drug. If the patient responds well, a controlled release preparation can be substituted and the dose can gradually be reduced.

Table 3.

Drug options for trigeminal neuralgia

| Drug | Level of evidence | Effect | Adverse effects | Suggested dose | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard treatment (reasonable evidence) | |||||

| Carbamazepine | 1 systematic review of 4 randomised controlled trials (n=160)15 | Number needed to treat for any pain relief 1.9 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.8); 72% of patients had excellent or good response | Drowsiness, ataxia, nausea, constipation; number needed to treat (minor) 3.7 (2.4 to 7.8); number needed to treat (major) not significant | 100 mg twice daily; increase as necessary by 50-100 mg every 3-4 days18; target range 400-1000 mg/day | Dose may need to be adjusted after 3 weeks because of enzyme induction |

| Second line (evidence weak or adverse effects limit use) | |||||

| Baclofen | 1 controlled trialw7 compared baclofen with placebo (n=10) | 7/10 improved with baclofen; 0/10 improved with placebo (P=0.05) | Drowsiness, hypotonia; avoid abrupt withdrawal | 10 mg three times daily; increase as necessary by 10 mg/day; target dose 50-60 mg daily18 | May be useful in patients with multiple sclerosis where its antispasticity effects can be harnessed |

| Gabapentin | 5 uncontrolled studies (n=123)18 | Good to excellent pain relief in 40%, any pain relief in 53% | Drowsiness, ataxia, diarrhoea; number needed to treat (minor) 2.5 (2.0 to 3.2) | 300 mg once daily; increase as necessary by 300 mg every 3 days in divided doses (three times daily); target dose 900-2400 mg daily | Widely used for trigeminal neuralgia although evidence is weak; evidence base in other types of neuropathic pains much stronger14 |

| Lamotrigine | 1 randomised controlled trial with lamotrigine as add on to carbamazepine or phenytoin (n=14)w8 | 10/13 improved on lamotrigine; 8/14 improved on placebo; not statistically significant | Drowsiness, dizzyness, constipation, nausea; in a randomised controlled trial the side effects were no different to placebo17 | 25 mg twice daily; increase by 50 mg weekly; target dose 200-600 mg daily | Probably better tolerated than carbamazepine but needs slow titration; may therefore have a role in the elderly or patients with multiple sclerosis who have less severe disease |

| Oxcarbazepine | 2 uncontrolled studies (n=21)18 | Pain relief in all 21 patients | Dizziness, fatigue, rash, and hyponatraemia | 300 mg twice daily; increase by 600 mg weekly; target dose 600-2400 mg daily | Evidence weak; structurally similar to carbamazepine although probably better tolerated18; used as first line drug in Scandinavia17 |

| Phenytoin | 3 uncontrolled studies (n=30)18 | 77% of patients reported some pain relief | Drowsiness, ataxia, dizziness, gum hypertrophy | 300 mg a day; dose may be altered to achieve therapeutic plasma concentrations | First drug used in the successful management of trigeminal neuralgia; little evidence but rapid dose titration and once daily dosing are advantages |

| Pimozide | 1 randomised controlled trial compared with carbamazepine (n=48)w9 | 100% improved on pimozide v 56% on carbamazepine | Extrapyramidal side effects, cardiac arrhythmia, sudden death18. | 2 mg once daily; increase as necessary by 2 mg weekly; target dose 2-12 mg/day. | An effective drug but use is severely limited by extrapyramidal effects and cardiac toxicity; potential of tardive dyskinesia limits use even more |

What is less clear is what to do if a patient is intolerant or allergic to carbamazepine, or if the drug is ineffective. In the absence of clear evidence of the effectiveness of other drugs, the choice between other agents can be made on the basis of adverse effects and ease of use (table 3).

If carbamazepine has adverse effects (table 3)

Oxcarbazepine is a prodrug of carbamazepine that is often better tolerated; it provides a logical,18 if largely unproved,17 alternative when carbamazepine has provided pain relief but has had unacceptable adverse effects. The risk of allergic crossreactivity between carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine is about 25%, so oxcarbazepine is best avoided in carbamazepine allergy.

Gabapentin is effective and widely used for neuropathic pain, though it lacks evidence in trigeminal neuralgia.14 Use of gabapentin therefore relies on the similarities between trigeminal neuralgia and other neuropathic pain, rather than their obvious differences. Familiarity with use in other neuropathic pain has led many clinicians to choose this as second line for trigeminal neuralgia.

Lamotrigine and baclofen have been suggested as alternative second line agents on the basis of small studies in trigeminal neuralgia (see table 2). In practice, lamotrigine needs to be titrated over many weeks and has limited value in severe pain. Other drugs to consider are phenytoin, clonazepam, valproate, mexiletine, and topiramate.17

If carbamazepine is ineffective

If pain relief is incomplete with carbamazepine options include adding a second agent or switching drugs. Similar considerations regarding choice of second line agent discussed above will apply.

Failure of medical therapy should prompt a review of the diagnosis19 (see table 1). If pain control cannot be achieved or drugs cause unacceptable adverse effects, surgical options should be considered.

What are the surgical treatment options?

Two types of surgical procedure are available (table 4):

Table 4.

Surgical procedures for trigeminal neuralgia

| Treatment | Possible adverse effects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Description | Invasiveness | Jaw weakness | Dysaesthesia | Ipsilateral deafness | Corneal numbness | Mortality | ||

| Microvascular decompression23 w10 | Compressing vessel separated from nerve root | Craniotomy | 0.2% | 0-2.4% | 1% | 1.8% | 0.4% (reported range 0-14%) | ||

| Radiofrequency thermocoagulation7 23 | Radiofrequency needle uses heat to lesion trigeminal root | Percutaneous | <10.5% | 5.2-24% | <1% | 10% | 0% | ||

| Glycerol rhizotomy7 23 | Glycerol injection produces chemical lesion of trigeminal nerve root | Percutaneous | 3% | 8% | 0% | 8% | 0% | ||

| Balloon compression7 23 w11 w12 | Inflated balloon compresses trigeminal nerve root | Percutaneous | 3-66% | 6.7-8.5% | 7% | 3% | 0% | ||

| Stereotactic radiosurgery7 23 w13 | Stereotactic techniques—gamma knife or linear accelaratorw14—used to lesion the trigeminal nerve root | Non-invasive | 0% | 1.4% | 0.14% | 0.35% | 0% | ||

Microvascular decompression, where the posterior fossa is explored and the compressing vessel and trigeminal nerve root are separated

Ablative treatment that lesion the trigeminal nerve in different ways.

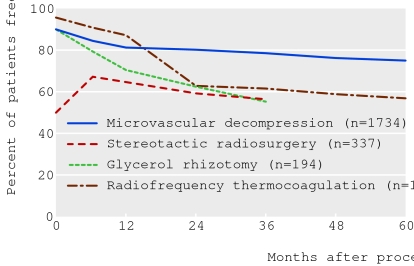

As with most surgical procedures the literature comprises mainly case series. Such series are difficult to compare (see box 3), as they vary in the populations of patients studied; diagnostic criteria, outcome measures, and follow-up methods used; and the presentation of the data.7 20 Despite this, broadly comparable high quality studies show relatively consistent responses to each procedure (fig 4).

Fig 4 Pain after surgical treatment of classic trigeminal neuralgia. Data come from series with broadly comparable diagnostic criteria, assessment criteria, and follow-up rates,6 7 w13 w15-w25 but combining the data has limitations (see box 3).

Predicting outcome for individual patients with confidence is difficult. Case series suggest that patients with classic trigeminal neuralgia, evidence of vascular compression, shorter duration of disease, and no previous surgery respond better to all treatment options.20 21 In such patients, microvascular decompression can be considered the “gold standard” surgical procedure, and it offers the best long term cure rates. Outcome also varies with the case load of operating surgeons.22

Deciding on which procedure to use involves choosing between two different types of risk. All procedures have a high initial response rate, except for stereotactic radiosurgery, which usually takes maximum effect at one to two months (fig 4).23 Microvascular decompression has the best chance of long term pain relief, with very low risk of facial sensory loss and other minor complications; however, it has a small risk of death (around 0.4%24). These risks vary according to other comorbidities that alter operative risk. In contrast, ablative procedures are less effective in the long term and more likely to produce facial numbness and other minor complications; indeed their effectiveness is often greatest when this is the case.7 They have a much lower risk of death or major complication, however, and are used to a greater extent in patients with high operative risk or as a partially diagnostic procedure in atypical disease. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery has recently been approved23 by the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, but access to this treatment is limited.

Making a decision between these options depends on the patient's perception of the two very different types of risk. Patients need to be well informed of the options, the related risks, and the likely outcomes to make such a decision. After having microvascular decompression most patients said they wish they had undergone the procedure sooner.25 Choosing between different ablative procedures, which seem to have similar effects, may be influenced by factors such as the range of adverse effects and the way in which the procedure is undertaken (see table 4).

The patient with trigeminal neuralgia who faces these difficult choices needs to be provided with the best available information and support from the doctors and surgeons involved in their care. They may find information from patient associations and other publications useful.

Patient's perspective

It was 1992 when I developed pain of a “shock nature” that seemed to run around the top of my teeth on the right side. I saw the dentist who said it was nothing to do with my teeth. My doctor put me on tegretol, which made me feel like a “zombie” and I became unsteady on my feet. By now the pain was travelling in towards the brain and down towards the jaw. It was excruciating, and the only way I could “hold” the pain was to grit my teeth together very hard until the pain died away. Sleep was not interrupted, but on waking the slightest movement of the mouth would set the spasms off again, so I didn't eat or talk much. I lost a lot of weight. I went to see a neurosurgeon who advised me to have an operation to “cuff” the responsible nerve, and despite the risks I agreed as the pain was intolerable. After the operation the pain had gone. I was alive again.

Ten years later the pain returned without warning. I saw the neurosurgeon again and this time I had a “radiofrequency lesion” of my trigeminal nerve. I am at present pain free and enjoying life as much as an 86 year old man can.

Research questions

What is the natural history of trigeminal neuralgia?

Why do some patients with vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve get the disease and others not?

Many drugs have some effect, but which is the best drug to use? A pragmatic comparative study is needed to clarify these choices.

Can the response to drugs and to different surgical interventions be predicted on clinical or radiological grounds?

Which ablative procedure is most effective for the fewest adverse effects?

How do ablative procedures compare with microvascular decompression?

Additional educational resources for patients

Zakrzewska JM. Insights—facts and stories behind trigeminal neuralgia. Gainesville, FL: Trigeminal Neuralgia Association, 2006

Trigeminal Neuralgia Association UK, Bromley BR2 9XS (URL: www.tna.org.uk; Tel: +44 020 84629122)—Provides excellent information and patient support groups

Trigeminal Neuralgia Association, Gainesville, FL 32605-6402, USA (URL: www.tna-support.org; Tel: +01 800 923 3608 or +01 352 331 7009)—Provides excellent information and patient support groups

Brain and Spine Foundation, London SW9 6EJ (URL: www.brainandspine.org.uk; Tel: +44 020 7793 5900)—Provides patient information and helpline

Supplementary Material

Contributors: LB and GF reviewed the literature and wrote the article. NKP reviewed and revised the article. GF is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Hall GC, Carroll D, Parry D, McQuay HJ. Epidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary care perspective. Pain 2006;122:156-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald BK, Cockerell OC, Sander JW, Shorvon SD. The incidence and lifetime prevalence of neurological disorders in a prospective community-based study in the UK. Brain 2000;123:665-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralh E, Kurland LT. Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Ann Neurol 1990;27:89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Headache Classification Subcommitee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders. 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 2004;24:1-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:117-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zakrzewska JM, Jassim S, Bulman JS. A prospective, longitudinal study on patients with trigeminal neuralgia who underwent radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the Gasserian ganglion. Pain 1999;79:51-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM. Systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 2004;54:973-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zakrzewska JM. Facial pain: neurological and non-neurological. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72(suppl 2):ii27-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zakrzewska JM. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain 2002;18:14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain 2001;124:2347-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng TM, Cascino TL, Onofrio BM. Comprehensive study of diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia secondary to tumors. Neurology 1993;43:2298-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel NK, Aquilina K, Clarke Y, Renowden SA, Coakham HB. How accurate is magnetic resonance angiography in predicting neurovascular compression in patients with trigeminal neuralgia? A prospective, single-blinded comparative study. Br J Neurosurg 2003;17:60-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, Carroll D, Jadad A, Moore A. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD001133. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ, Edwards JE, Moore RA. Gabapentin for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD005452. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Carbamazepine for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD005451. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Zakrzewska JM, Lopez BC. Quality of reporting in evaluations of surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: recommendations for future reports. Neurosurgery 2003;53:110-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zakrzewska JM, Lopez BC. Trigeminal neuralgia. Clin Evid 2005;1669-77. [PubMed]

- 18.Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Drug therapy of trigeminal neuralgia. Expert Rev Neurother 2006;6:429-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato J, Saitoh T, Notani K, Fukuda H, Kaneyama K, Segami N. Diagnostic significance of carbamazepine and trigger zones in trigeminal neuralgia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2004;97:18-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM. Stereotactic radiosurgery for primary trigeminal neuralgia: state of the evidence and recommendations for future reports. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:1019-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li ST, Pan Q, Liu N, Shen F, Liu Z, Guan Y. Trigeminal neuralgia: what are the important factors for good operative outcomes with microvascular decompression. Surg Neurol 2004;62:400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalkanis SN, Eskandar EN, Carter BS, Barker FG. Microvascular decompression surgery in the United States, 1996 to 2000: mortality rates, morbidity rates, and the effects of hospital and surgeon volumes. Neurosurgery 2003;52:1251-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim JNW, Ayiku L. The clinical efficacy and safety of stereotactic radiosurgery (gamma knife) in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2004. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/IPG85.

- 24.Ashkan K, Marsh H. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in the elderly: a review of the safety and efficacy. Neurosurgery 2004;55:840-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zakrzewska JM, Lopez BC, Kim SE, Coakham HB. Patient reports of satisfaction after microvascular decompression and partial sensory rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery 2005;56:1304-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.