Abstract

Background

We previously reported significantly higher one-year survival in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction randomized to receive early revascularization compared with randomization to receive initial medical stabilization.

Methods

The 302 patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock and an average age of 66 years at randomization in the SHOCK trial had vital status followed long-term, ranging from one to 11 years (median 6 years for survivors). Secondary endpoints included three and six-year survival.

Results

The group difference in survival of 13 absolute percentage points at one year favoring those assigned to early revascularization remained stable at three and six years (13.1% and 13.2%, respectively; logrank P=0.028). At six years, overall survival rates were 32.8% and 19.6% in the early revascularization and initial medical stabilization groups, respectively. Amongst the 143 hospital survivors, the 6-year survival rates were 62.4% vs. 44.4% with annualized death rates of 8.3% and 14.3% and 8.0% and 10.7% for 1 year survivors, respectively. There was no significant interaction between any subgroup and treatment effect.

Conclusions

Almost two-thirds of hospital survivors with cardiogenic shock who were treated with early revascularization are alive six years later. A strategy of early revascularization results in a 13.2% absolute and 67% relative improvement in six-year survival compared with initial medical stabilization. Early revascularization should be utilized for patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock due to left ventricular failure.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, Cardiogenic shock, Thrombolysis, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Coronary artery bypass graft surgery, Long-term survival

The incidence of cardiogenic shock (CS) complicating acute myocardial infarction (MI) has remained constant over 25 years.1–3 Although in-hospital mortality declined for the first time in the mid-1990’s, the overall mortality rate is still 60 percent1,3 and CS remains the major cause of death for patients hospitalized with acute MI.2–4 We previously reported the initial and one-year results of the randomized SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK (SHOCK) trial.5,6 This trial demonstrated that a strategy of early revascularization in patients with CS resulted in a non-significant reduction in 30-day mortality from 55% to 46% when compared with a strategy of initial medical stabilization, a significant 13 absolute percentage points reduction in one-year mortality and good functional status at one year for the majority of survivors.7,8,9 We report here the long-term outcome of the SHOCK trial cohort.

METHODS

Trial Design

The SHOCK trial design has been previously reported.10 Briefly, patients with acute MI who developed CS due to predominant left ventricular failure within 36 hours of MI onset were eligible for the trial if the electrocardiogram showed ST elevation or Q waves, posterior infarction, or new or presumably new left bundle block. Randomization had to be accomplished within 12 hours of shock diagnosis. Strict clinical and hemodynamic criteria for shock were required.10 The trial enrollment period was April 1993 through November 1998. A long-term study funded by the NHLBI in 2000 ascertained long term vital and functional status, with 3 and 6 year mortality as specified endpoints. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board or Ethics Committee at all participating centers and written informed consent was obtained from all patients or a surrogate prior to randomization.

Patients randomized to a strategy of attempted early revascularization were required to undergo either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), as soon as possible and within 6 hours of randomization. Those randomized to initial medical stabilization were recommended to receive thrombolytic therapy (utilized in 63 percent) and allowed to have PCI or CABG after 54 hours following randomization, and revascularization was performed in 25%. Subgroup factors, with prespecified cutoff points for hemodynamic and shock timing variables, were prespecified in the protocol except for creatinine, where the upper quartile was compared to all others.

Data Collection Methods

One-year follow-up was obtained on all patients; an updated vital status was obtained for all patients in 1999–2000, regardless of randomization date and, for centers participating in the trial continuation, follow-ups were conducted annually until 2005. Post-discharge vital status was obtained via telephone, review of medical records, and search of National Death Registries and the Social Security Death Index (SSDI) for U.S. patients

Statistical Methods

Survival times were calculated as the time from randomization to the time of death or last known follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimator and the logrank test were used to analyze continuous survival time, and Cox proportional hazards regression modeling12 was used to test the interaction of treatment assignment and subgroup factors, as well as multivariate modeling of risk factors. A clinical model included readily available patient, MI and shock characteristics, and a second stage model added left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and right heart catheterization data. Survival times were censored at the date of heart transplantation. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS® 13 and SPlus® 14.

Patient Sample

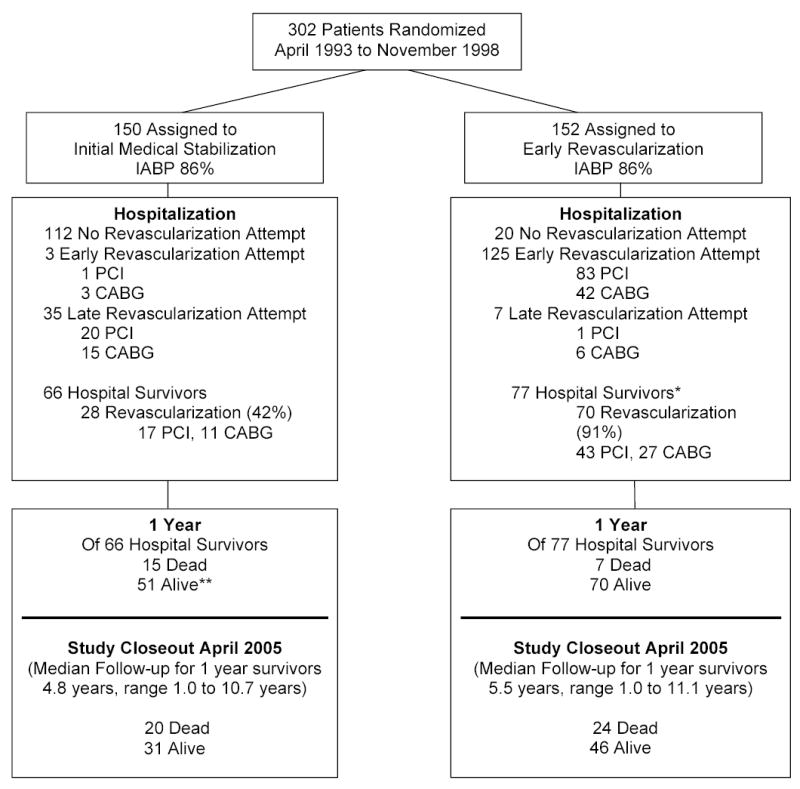

Patients were randomized at 29 international sites; 152 assigned to emergency early revascularization (ERV) and 150 were assigned to initial medical stabilization (IMS) (Figure 1). At randomization, patients were a mean (SD) of 66 (11) years old, 97 (32%) were female and 98 (32%) 5 had a history of MI. Patient characteristics were balanced between the two arms, except more patients in the IMS group had prior CABG.5 Shock most often developed early after infarct onset (median 5.5, interquartile range 2.3 to 14.1 hours). The characteristics of patients who were not transplanted and discharged alive following the shock hospitalization were balanced by treatment arm, including with respect to prior CABG. Amongst hospital survivors, patients were followed for up to 11 years with a median of 5.9 years (interquartile 1.9 to 8.1); 3 (1 IMS,2 ERV) patients were followed for only 1 year and 15 additional patients (8 IMS,7 ERV) were followed for less than two years at sites that did not participate in long term follow up.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Diagram

IABP = Intra-aortic balloon pump

*Survivors count excludes 1 patient in ERV group who underwent heart transplantation and was discharged alive from the hospitalization for shock.

**One patient in the IMS group who successfully underwent heart transplantation after discharge but prior to one year post-randomization was censored at the date of transplantation.

RESULTS

Survival

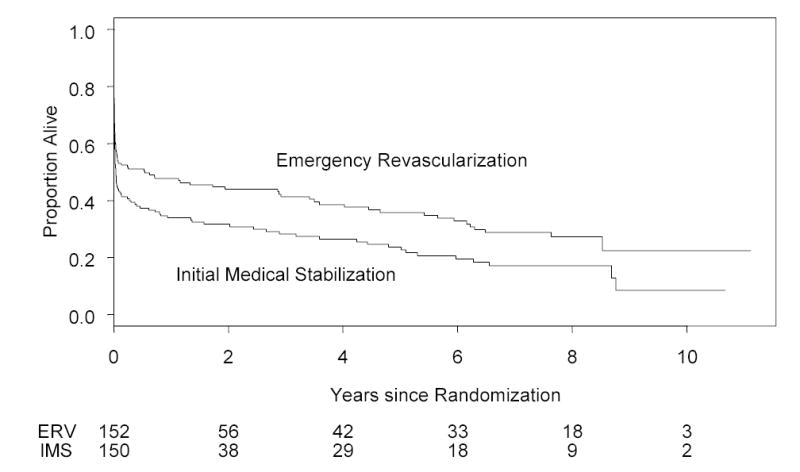

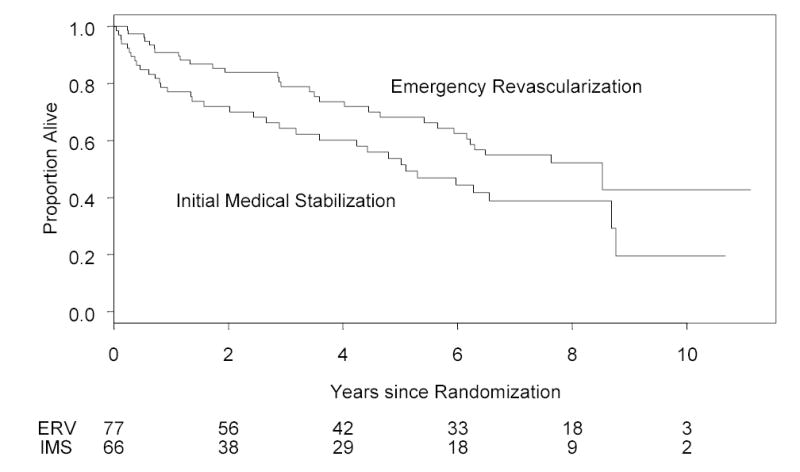

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves (Figure 2) were significantly different (P=0.028), with a 13.1% (95% confidence interval (CI) −2.4% to 28.5%) and 13.2% (95% CI −1.9% to 28.3%) absolute difference in survival at 3 and 6 years favoring ERV. The Cox model hazard ratio for death for ERV vs. IMS is 0.74 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.97). Amongst hospital survivors, the annualized death rates for ERV and IMS groups were 8.3 and 14.3 deaths per 100 patient-years (Figure 3). A disproportionate number of deaths occurred in the first year following CS in the IMS group (26.4 per 100 patient-years) relative to the ERV group (9.5 deaths per 100 patient-years)with annualized death rates of 8.0 and 10.7 deaths per 100 patient-years for the ERV and IMS groups after the first year. The survival difference between treatment groups was nearly constant after 2 years.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier long term survival of 152 patients assigned to emergency early revascularization and 150 patients assigned to initial medical stabilization. Logrank test P= 0.028. Risk set sizes are shown at bottom. The survival rates in the ERV and IMS groups, respectively, were 41.4% vs 28.3% at 3 years and 32.8% vs. 19.6% at 6 years. With exclusion of 8 patients with aortic dissection, tamponade, or severe mitral regurgitation identified shortly after randomization, the survival curves remained significantly different (P=0.023) with a 14.0% absolute difference at 6 years.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier long term survival based on 143 patients discharged alive following the hospitalization for shock, stratified by emergency early revascularization vs. initial medical stabilization groups. Logrank test P= 0.029. Risk set sizes are shown at bottom. The survival rates in the ERV and IMS groups, respectively, were 78.8% vs 64.3% at 3 years and 62.4% vs. 44.4% at 6 years.

Risk Stratification and Subgroups

Multivariate modeling revealed that older age (HR 1.23 per 10 years, P=0.007), shock on admission (HR 1.68, P=0.01), creatinine ≥1.9 mg/dl (HR 2.30, P<0.0001), a history of hypertension (HR 1.40, P=0.03) and non-inferior MI location (HR=1.50, P=0.02) were independent risk factors for lower survival rates in a clinical model (N=230). The model that also incorporated hemodynamic measurements and LVEF (N=148) demonstrated that only older age (HR=1.25 per 10 years, P=0.035), lower LVEF (HR=1.22 per 5%, P<0.0001), and creatinine ≥ 1.9 mg/dl (HR=1.96, P=0.012) are independently associated with death.

Long-term survival analysis of the entire cohort, identified no interactions between treatment assignment and any subgroup factor, including age (≤75 vs ≥ 75 years), sex, diabetes, prior MI, hypertension, non-inferior MI, transfer admission, shock timing (shock on admission vs delayed shock, shock < 6 vs ≥6 hours post MI), thrombolytic administered, clinical site location, presence or absence of rapid reversal of systemic hypoperfusion with IABP, creatinine (<1.9 vs. ≥1.9 mg/dl), pulmonary wedge pressure (< 25 vs. ≥ 25 mmHg), cardiac index (< 2 vs. ≥ 2.0 m/min/L2), ejection fraction (<25 vs. ≥25%), presence vs. absence of left main disease, and single vs. multivessel disease.

Early Revascularization for Cardiogenic Shock

Amongst hospital survivors who were assigned to ERV, there was no difference (P=0.51) in long-term survival between PCI and CABG as the primary emergency mode of revascularization for the 27 treated by CABG-treated hospital survivors assigned to ERV, who were of similar age, were 7.0 and 9.3 deaths per 100 patient-years, despite differences in coronary anatomy and diabetes. 15

The association in the ERV group between one-year mortality and timing of revascularization from MI onset was examined as a continuous variable and using timing categories <4 hours post-MI, in 2-hour increments thereafter, and ≥ 10 hours post-MI. No statistically significant association was found due to small strata (11 patients per stratum except for 99 patients at ≥ 8 hours), but one-year mortality estimates increased from 0 to 8 hours and then decreased, presumably due to survivor bias (<4 hours, 36%; 4 to < 6 hours, 55%; 6 to <8 hours, 82%; ≥ 8 hours, 48% one-year mortality).

DISCUSSION

A strategy of early revascularization resulted in a 67% improvement in six-year survival in this randomized trial involving patients with MI complicated by CS due to predominant LV failure. The large survival benefit (130 lives saved per 1000 patients treated or 8 patients need to be treated to save one life) was sustained throughout the follow-up period of up to 11 years. After one year, the survival curves remain parallel with an annualized mortality rate of 8.0 deaths per 100 patient-years for early revascularization and 10.7% for initial medical stabilization. These annual mortality rates are similar to those reported for a comparably aged broad cohort of post-PCI patients and a few percentage points higher than a large cohort of unselected post-MI patients.16 The overall long-term survival of CS patients who survived the early period (30 days) in prior studies varies widely, ranging from 32% at 6 years to 55% at 11 years 9, 18–19 and is related to the definition of shock, risk profile and management of the cohort.

In this report, the clinical and MI factors that are independently associated with a higher long term mortality rate, regardless of treatment assignment, are similar to those associated with death at 30 days in the SHOCK Trial and Registry. 20 In a model that also incorporates hemodynamics and LVEF the latter is strongly independently associated with both short-term and long-term outcome. However, hemodynamic variables measured close to shock onset that are highly predictive at 30 days (e.g., cardiac index, cardiac power, stroke work and systolic blood pressure on support) 20, 21 are not associated with long-term outcomes. In general, variables we observed to be independently associated with long-term outcome after shock (age, LVEF and serum creatinine) have been consistently demonstrated to be similarly associated with long-term outcome in patients with a variety of cardiovascular disease presentations.

The higher long-term survival with early revascularization was remarkably consistent among multiple subgroups. The previously reported differential treatment effect at 1 year for the elderly (age ≥75 years) was no longer statistically significant.5 The findings at 1 year appear to be due to an imbalance that occurred by chance; the elderly patients assigned to medical stabilization had a higher baseline ejection fraction than those assigned to early revascularization and an associated high survival rate, similar to patients < 75 years who were assigned to medical stabilization, despite the powerful prognostic importance of age.20, 22 Furthermore, the larger non-randomized SHOCK Registry, demonstrated a markedly lower adjusted risk of in-hospital mortality for those ≥ 75 years (n=257) who were clinically selected to undergo early revascularization.23 Other large registries have shown similar results.24, 25 The revised American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association ST Elevation MI guidelines indicate that primary or rescue PCI or CABG is reasonable for selected patients age ≥75 years with cardiogenic shock (class IIa recommendation).26 The survival benefit of urgent revascularization is similar for patients who develop shock late after MI as for those with early shock. Furthermore, there was benefit of revascularization throughout the SHOCK trial enrollment time window, which included up to 48 hours post MI and 18 hours post shock onset. The current data are consistent with prior studies of time to reperfusion in acute MI with or without shock which demonstrate a strong survival advantage for earlier reperfusion, although we did not observe a statistically significant relationship.27–29 This is likely due to inherent selection bias, with more stable patients surviving to undergo later revascularization and the limited cohort size.

Our data demonstrate that the substantial survival benefit for early revascularization of patients with CS is maintained over long term follow up. They therefore lend further support to the need to identify quickly all patients with CS who are candidates for early revascularization, as recommended in the guidelines.26 Early revascularization has been increasingly utilized in recent years in tertiary care centers, but only approximately 60% of those < 75 years old received it in these select US centers in 2004.1 Furthermore, the rate of transfer of CS patients out of hospitals that cannot perform revascularization is 38% and did not change from 1998 –2001.30 The rate of revascularization for shock in Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events hospitals was only 43% from 1999–2001.31 These rates of revascularization are too low in light of the current study’s finding of the striking durability of treatment effect.

Limitations

One limitation of this analysis is the shorter follow-up period of patients from SHOCK centers that did not participate in the long-term follow-up component conducted from 2000 to 2005. However, all but two centers (3 patients) completed a vital status confirmation in 1999 regardless of randomization date, and only 18 patients had follow-up less than two years. The use of the SSDI may have led to overestimation of the long-term event rate since patients lost to follow-up who did not appear in the SSDI were recorded as alive only as of the date last seen at or contacted by the SHOCK center. We have limited information on the use of very late revascularization (after hospital discharge) and implantable cardio-defibrillators.

Conclusion

Patients with cardiogenic shock complicating ST elevation MI undergoing early revascularization with PCI or CABG surgery have substantially improved long-term survival compared with patients having initial intensive medical therapy followed by no or late in-hospital revascularization. These data further underscore the need for direct admission or early transfer of patients in cardiogenic shock to designated tertiary care shock centers with demonstrated expertise in acute revascularization and advanced intensive care of these high risk patients.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of SHOCK investigators, coordinators and patients, and the NHLBI Project Officer, Patrice Desvigne-Nickens, MD.

The SHOCK Trial was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL50020 and R01-HL49970 for long term follow up). The sponsor had no role in the design or conduct of the study or in the collection, management, or analysis of the data, other than oversight provided by the NHLBI Project Office and by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Drs. Hochman and Sleeper had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Appendix

Sites that did long-term telephone follow up.

St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver: J. Webb and T. Kot; Vancouver General Hospital: C. Buller and R. Fox; St. Lukes-Roosevelt Hospital Center: J. Slater and D. Tormey; New York Hospital Center, Queens: P. Stylianos and M. Brown; Winthrop University Hospital, New York: R. Steingart and M.E. Coglianase; University of Alberta: W. Tymchak and L. Harris; Flinders Medical Center, South Australia: P. Aylward and S. Kovaricek; Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Belgium: J. Col and R. Lauwers; Green Lane Hospital, New Zealand: H. White and K. Speed; CHR Citadelle, Belgium: J. Boland and M. Massoz; SUNY at Stony Brook, New York: W. Lawson and T. Adkins; New York Hospital Cornell: D. Miller.

Sites that searched vital status.

Boston University Hospital: A. Jacobs and D. Fine; University of Arkansas: J. Saucedo and S. Canterbury; Baystate Medical Center: M. Porway and J. Provencher; Montefiore Hospital of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine; M. Menegus and B. Levine; JD Weiler Hospital of Albert Einstein College of Medicine: R. Forman, and P. Sicilia; University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ: S. Palmeri.

Contributor Information

Judith S. Hochman, Cardiovascular Clinical Research Center, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Lynn A. Sleeper, New England Research Institutes, Watertown, Mass.

John G. Webb, St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Vladimir Dzavik, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Christopher E. Buller, Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Philip Aylward, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, Australia

Jacques Col, Cliniques Universitaires St-Luc, Brussels, Belgium

Harvey D. White, Green Lane Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand

References

- 1.Babaev A, Frederick PD, Pasta DJ, et al. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. JAMA. 2005;294:448–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg RJ, Gore JM, Alpert JS, et al. Cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. Incidence and mortality from a community-wide perspective, 1975–1988. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1117–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, et al. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1162–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Becker RC, Gore JM, Lambrew C, et al. A composite view of cardiac rupture in the United States National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1321–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:625–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, White HD, et al. One-year survival following early revascularization for cardiogenic shock. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:190–192. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sleeper LA, Ramanathan K, Picard MH, et al. Functional capacity and quality of life following emergency revascularization for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger PB, Tuttle RB, Holmes DR, et al. One-year survival among patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock, and its relation to early revascularization. Circulation. 1999;99:873–878. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes DR, Jr, Hasdai D, White J, Berger PB. Long-Term Outcome in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(5 Supp A):274A. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Godfrey E, et al. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock: An international randomized trial of emergency percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty/coronary artery bypass graft – trial design. Am Heart J. 1999;137:313–21. doi: 10.1053/hj.1999.v137.95352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochman JS, Buller CE, Sleeper LA, et al. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction-etiologies, management and outcome; overall findings of the SHOCK Trial Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00879-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) J Royal Stat Soc Series B. 1972;74:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 13.SAS System for Windows version 9.1, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC: 2004.

- 14.S-PLUS for Windows version 6.2, Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA; 2003.

- 15.White HD, Assmann SF, Sanborn TA, Jacobs AK, Webb JG, Sleeper LA, Wong CK, Stewart JT, Aylward PE, Wong SC, Hochman JS. Comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting after acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock (SHOCK) trial. Circulation. 2005;112(13):1992–2001. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes DR, Jr, Kip KE, Kelsey SF, Detre KM, Rosen AD. Cause of death analysis in the NHLBI PTCA Registry: results and considerations for evaluating long-term survival after coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:881–887. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alter DA, Naylor CD, Austin PC, Tu JV. Long-term MI outcomes at hospitals with or without on-site revascularization. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:2101–2108. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindholm MG, Kober L, Boesgaard S, Torp-Pedersen C, Aldershvile J on behalf of the TRACE study group. Cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Prognostic impact of early and late shock development. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:258–265. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tedesco JV, Williams BA, Wright RS, et al. Baseline comorbidities and treatment strategy in elderly patients are associated with outcome of cardiogenic shock in a community-based population. Am Heart J. 2003;146:472–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleeper LA, Jacobs AK, LeJemtel T, Webb JG, Hochman JS. A mortality model and severity scoring system for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;102(18):3840 II-795. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fincke R, Hochman JS, Lowe AM, et al. for the SHOCK Investigators. Cardiac Power is the Strongest Hemodynamic Predictor of Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock: A Report from the SHOCK Trial Registry . J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzavik V, Sleeper LA, Pickard M, et al. for the SHOCK Investigators. Outcome of patients aged ≥75 years in the SHOCK Trial: Do elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock respond differently to emergent revascularization? Am Heart J. 2005;149:1128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dzavik V, Sleeper LA, Cocke TP, et al. Early Revascularization is Associated with Improved Survival in Elderly Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock: A Report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(9):828–37. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00844-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dauerman HL, Ryan TJ, Jr, Piper WD, et al. Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Among Elderly Patients in Cardiogenic Shock: A Multicenter, Decade-long Experience. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dauerman HL, Goldberg RJ, Malinski M, Yarzebski J, Lessard D, Gore JM. Outcome sand early revascularization for patients ≥65 years of age with cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:844–848. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction) Circulation. 2004;110(9):e82–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation. 2004;109:1223–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121424.76486.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brodie BR, Stuckey TD, Muncy DB, et al. Importance of time-to-reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction with and without cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2003;145:708–15. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cannon CP, Gibson Cm, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of symptom-onset-to balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2941–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.22.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babaev A, Every N, Frederick P, Sichrovsky T, Hochman JS. Trends in Revascularization and Mortality in Patients with Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction. Observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2002;106 (19):1811. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dauerman HL, Goldberg RJ, White K, Gore JM, Sadiq I, Gurfinkel E, Budaj A, Lopez de Sa E, Lopez-Sendon J Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. GRACE Investigators. Revascularization, stenting, and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:838–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02704-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]