Abstract

We studied factors affecting major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II)-restricted presentation of exogenous peptides at the surface of macrophages. We have previously shown that peptide presentation is modulated by surface-associated proteolytic enzymes, and in this report the role of the binding of MHC-II molecules in preventing proteolysis of exogenous synthetic peptides was addressed. Two peptides containing CD4 T-cell epitopes were incubated with fixed macrophages expressing binding and non-binding MHC-II, and supernatants were analysed by high-performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry to monitor peptide degradation. The proportion of full-length peptides that were degraded and the number of peptide fragments increased when non-binding macrophages were used, leading to reduction in peptide presentation. When MHC-II molecules expressed on the surface of fixed macrophages were blocked with monoclonal antibody and incubated with peptides and the supernatants were transferred to fixed macrophages, a significant reduction in peptide presentation was observed. Peptide presentation was up-regulated at pH 5·5 compared to neutral pH, and the latter was found to be the pH optimum of the proteolytic activity of the surface enzymes involved in the degradation of exogenous peptides and proteins. The data suggest that MHC-II alleles that bind peptides protect them from degradation at the antigen-presenting cell surface for presentation to CD4 T cells and we argue that this mechanism could be particularly pronounced at sites of inflammation.

Keywords: antigen presentation, macrophages, major histocompatibility complex class II, T cells

Introduction

Soluble and particulate antigens are enzymatically degraded in acidic endocytic compartments of a variety of antigen-presenting cell (APC) types to generate antigenic peptides that load newly synthesized major histocompatibility class II (MHC-II) molecules, constituting a so-called classical MHC-II-restricted antigen presentation pathway.1–3 MHC-II molecules on the surface of APC can also directly bind and present extracellular peptide epitopes4 and chemically or enzymatically fragmented proteins,5 as well as some denatured intact proteins6–10 constituting an alternative MHC-II-restricted antigen presentation pathway.11 Moreover, cell surface MHC-II molecules can be directly loaded with some native proteins in which epitopes are located in structurally flexible regions.12,13 Several factors have been described to facilitate the formation of peptide–MHC-II complexes on the cell surface of APC, including the cell-surface expression of the MHC-II chaperone DM, which plays an important role in loading peptides on cell surface MHC-II molecules in both B cells and immature dendritic cells.14,15 Aminopeptidase N, and possibly other cell-surface enzymes, may also influence presentation by MHC-II molecules by processing or trimming of proteins and/or peptides on the cell surface.16–19

Purified MHC-II molecules have been shown to bind peptides containing T-cell epitopes and partially to protect them from degradation by exogenously added proteolytic enzymes, such as cathepsin B, pronase E and chymotrypsin, for presentation to CD4 T cells in cell-free systems,20,21 although the factors influencing the rescue of exogenous peptides by MHC-II expressed at the cell-surface of APC for presentation to CD4 T cells are not well understood. In our previous study we showed that enzymes of the metallo-, aspartic- and serine-proteinase families are involved in destructive processing of exogenous peptides at the surface of macrophages.22 In this report, we show that binding to MHC-II molecules at the surface of APC may protect a significant proportion of exogenous peptides from proteolytic degradation.

Materials and methods

Mice

The congenic BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.K mice (H-2k) were obtained from Harlan UK Ltd, Oxfordshire, UK.

Synthetic peptides

The following synthetic peptides bearing CD4 T-cell epitopes were used in this study: p14–33, 14KEALDKYELENHDLKTKNEG33, which contains the epitope M517–31/Ed of the type 5M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes (underlined),23,24 and p381–394, 381LIQEMLKTMESINQ394, which contains epitope SipC381–394/Ad of the Salmonella invasion protein C (SipC) of Salmonella typhimurium.25 Peptides were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and their sequences were confirmed by mass spectrometry. Peptides p14–33 and p381–394, modified with N-terminal biotin, were purchased from Sigma-Genosys Ltd, Cambridge, UK.

Cells

Macrophages were grown from femoral bone marrow cells of congenic BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.K (H-2k) mice and were maintained in tissue culture medium (RPMI-1640 medium containing 3·0 mm l-glutamine, 0·05 mm 2-mercaptoethanol and 10% fetal bovine serum) supplemented with 5% horse serum, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 10 mm HEPES buffer and 10% L929-fibroblast-conditioned medium as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor.22,26,27 All ingredients were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Dorset, UK. After 5–6 days of culture in bacteriological Petri dishes, macrophages were transferred to 48-well flat-bottomed plates (Bibby Sterilin Ltd, Staffordshire, UK) to establish a monolayer. T-cell hybridoma HX17 specific for the epitope M517–31/Ed of the type 5M protein, and C4C1 T-cell hybridoma specific for the epitope SipC381–394/Ad of the protein SipC have been described previously.25,28

Proliferation assay

Mice were immunized in the footpad with 30 μg synthetic peptides p14–33 and p381–394 in Hunter's TiterMax adjuvant (Sigma). Seven days later, peptide-induced proliferative responses of the popliteal lymph node cells (2 × 105/well) were assayed in triplicate in round-bottomed 96-well Microtitre plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, New Jersey, NJ) in 150-μl tissue culture medium for 72 hr at 37° in a humidified CO2 incubator. Synthetic peptides were used at 30, 10 and 3 μg/ml (20 μm, 6 μm and 2 μm). Triplicate cultures were labelled with 14·8 kBq of [methyl-3H]thymidine (TRA310, specific activity 307 MBq/mg; Amersham International plc., Buckinghamshire, UK) for the last 16 hr, and harvested on glass fibre membranes using a cell harvester (Micromate 196, Canberra Harwell Ltd, Didcot, Oxfordshire, UK). The amount of radioactivity in each well was quantified by direct beta counting (Matrix 9600, Packard Instrument Company, Meridan, CT).

Antigen presentation assay

Macrophages were fixed with 1·0% paraformaldehyde (w/v in Hanks' balanced salt solution; HBSS) for 4 min to block antigen internalization. This treatment has been previously shown to preserve cell surface-associated enzyme activity without exposing lysosomal enzymes.17,22 To test the effect of pH on peptide presentation, HBSS pH 7·2; and 0·1 m sodium citrate buffers with pH 6·5 and pH 5·5 were used. Cells were washed and incubated with the following enzyme inhibitors (Sigma) for 30 min: (1) phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF, 3 mm, inhibitor of serine proteinases)29, (2) (2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methyl-butane (E-64d, 10 μm, inhibitor of cysteine proteinases),30 (3) pepstatin A (0·5 mm, inhibitor of aspartic proteinases)31 and (4) 1,10-phenanthroline (100 μm, inhibitor of metalloproteinases)32 as described previously.22 Synthetic peptides were added at 40 μm concentration in HBSS and incubated for 24 hr. In some experiments, macrophages were treated with anti-MHC-II monoclonal antibody (mAb; M5/114.15.2, anti-Aβb,d,q, anti-Ed,k, ATCC, TIB120, 1 : 250) for 30 min, fixed and washed to remove unbound antibodies before incubation with peptides for a further 24 hr. In transfer experiments supernatants were transferred to a 48-well plate with fixed BALB/c macrophages and incubated for 24 hr.

All experimental steps prior to adding T-cell hybridomas to the assays were performed in serum-free medium. Wells were washed to remove inhibitors and unbound peptides before T-cell hybridoma cells were added at 5 × 104/well for 24 hr in tissue culture medium, and the interleukin-2 (IL-2) content of hybridoma supernatants was used as a measure of the T-cell response to the presented peptide. Supernatants were collected and frozen prior to IL-2 assay, measured as the proliferative response of the IL-2-dependent cytotoxic T-cell line-2 [CTLL-2, American Type Culture Collection (Teddington, Middlesex, UK), TIB 214, 3 × 104/well] for 24 hr. CTLL-2 cells were labelled with [methyl-3H]thymidine as described above, and results are shown as mean counts per minute (c.p.m.) ± standard error of the mean. All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Peptide binding assay

Macrophages from BALB/c or BALB.K mice were added at 105/well in 96-well flat-bottomed plates (Greiner Bio One, Stonehouse, UK) and fixed as described above. Three-fold dilution series of N-terminally biotinylated peptides p14–33 and p381–394 (starting concentration 40 μm) were added in 0·1 m sodium citrate buffer pH 5·5 and incubated for 24 hr at 37°. In peptide dissociation experiments, plates were washed to remove extracellular peptide, 50 μl of 0·1 m sodium citrate buffer pH 5·5 was added to the first plate for 24 hr and then transferred to another plate with fixed BALB/c macrophages. In some experiments, N-terminally biotinylated peptides p14–33 and p381–394 at 20 μm were incubated with a two-fold dilution series of mAb (BD-PharMingen, Oxford, UK, starting concentration 10 μg/ml) specific for Kd, Ad/Ed and CD1d. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), plates were incubated with 1·0 μg/ml streptavidin–peroxidase polymer (Sigma) for 1 hr at room temperature. The reaction was developed with the liquid substrate system for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (Sigma) for 30 min at 37° and stopped with 1% sodium dodecyl sulphate. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm.

Azocasein protease assay

Protease activity of fixed macrophage was determined by measuring the release of azocasein-derived amino acids and small peptides, as described elsewhere33 with the following modifications. Adherent macrophages from BALB/c and BALB.K mice (2 × 105/well, 48-well plates) were fixed and washed before 200 μl of 1% azocasein (Sigma) was added in HBSS pH 7·2 or in 0·1 m sodium citrate buffers with pH 6·5 or pH 5·5. After incubation at 37° for 24 hr, proteolysis was stopped by adding 200 μl of 20% cold trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation at 15 000 g for 5 min, 200 μl of the supernatant was collected and azocaseinase activity was determined by reading optical density at 405 nm.

HPLC analysis and mass spectrometry

To ensure consistent identification of peptide cleavage fragments, fixed macrophages were incubated with 80 μm synthetic peptides dissolved in HBSS for 24 hr. Peptide cleavage fragments were analysed on an Agilent 1100 system by RP-HPLC using an Aquapore RP-300 (C-8) column (4 × 5 mm), and a 30-min gradient from 0% to 70% acetonitrile in 0·05% trifluoroacetic acid at the flow rate of 1·0 ml/min. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry was performed as a service by the Department of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Aberdeen using a PE Biosystems Voyager-DE STR Laser Desorption Time of Flight Spectrometer. Samples were prepared by mixing 1 : 1 with a matrix solution (1%α-cyano-4-hydroxy-cinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile, 0·1% trifluoroacetic acid). Samples were placed as 1-μl matrix solution spots, and the external calibration standards were angiotensin-1 and neurotensin.

Results

Exogenous peptides bind MHC-II molecules at the surface of macrophages

We investigated the degradation of synthetic peptides p14–33 and p381–394 containing H-2d-restricted CD4 T-cell epitopes from the type 5M protein of Streptococcus pyogenes23,24 and the Salmonella invasion protein C (SipC) of Salmonella typhimurium25, respectively, on the surface of bone-marrow macrophages from congenic BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.K (H-2k) mice. To establish the binding pattern of peptide epitopes to the surface of macrophages, N-terminally biotinylated peptides were incubated with fixed BALB/c and BALB.K macrophages and binding was measured by ELISA using streptavidin–peroxidase polymer. Both peptides bound to the surface of BALB/c macrophages, but bound only negligibly to BALB.K macrophages (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Binding biotinylated peptides at the surface of fixed macrophages. (a) To test direct peptide binding, dilution series of N-terminally biotinylated peptides p14–33 (squares) and p381–394 (circles) shown at the x-axis were incubated with fixed macrophages (Mφ) from MHC-congenic BALB/c (filled symbols) or BALB.K (empty symbols) mice. (b) To test peptide dissociation, plates were washed, incubated with 0·1 m sodium citrate buffer, pH 5·5 and transferred to another plate with fixed BALB/c macrophages. After incubation with streptavidin–peroxidase polymer, both reactions were developed with liquid substrate system for ELISA and absorbance was measured at 405 nm. N-terminally biotinylated peptides p14–33 (c) and p381–394 (d) were added at 20 μm concentration to fixed BALB/c macrophages in the absence (filled squares) or presence of the two-fold dilution series of mAb specific for Kd (empty squares) Ad/Ed (filled circles) or CD1d (empty circles) shown at the x-axis. The background absorbance in the absence of peptides is indicated by diamonds. Error bars denote SEM. The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

We also investigated peptide dissociation from the surface of fixed macrophages. Fixed BALB/c or BALB.k macrophages were incubated with peptides, plates were washed and incubated further to allow peptide dissociation. Supernatants were transferred to a plate of fixed BALB/c macrophages to determine whether peptides were present that could be presented to T-cell hybridomas. Data in Fig. 1(b) show that both peptides dissociated from the first plate with fixed macrophages and were captured by the fixed macrophages on the second plate.

Binding of both p14–33 and p381–394 to the surface of fixed BALB/c macrophages was reduced in the presence of anti-Ad/Ed mAb (by 79% and 95%, respectively), but not by anti-Kd or anti-CD1d mAb (Figs 1c,d). The data suggest that binding to BALB/c macrophages, but not to BALB.K macrophages, was largely a result of association with the restricting H-2d molecules. Peptide-immunized BALB.K mice failed to respond to peptides p14–33 and p381–394 in lymphocyte proliferation assays (data not shown), confirming that p14–33 and p381–394 containing known H-2d-restricted T-cell epitopes were bound only poorly, or not at all, by H-2k molecules.

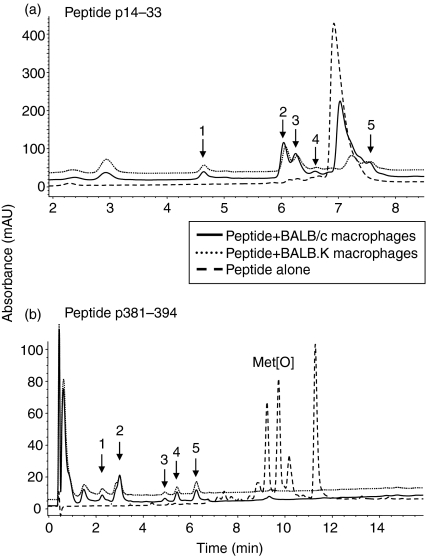

MHC class II-mediated rescue of exogenous peptides from proteolytic degradation at the cell surface of macrophages

We addressed whether binding to surface MHC-II molecules rescues exogenous peptides from proteolytic degradation by surface enzymes. Peptides were incubated with fixed BALB/c (binding MHC-II) or BALB.K (non-binding MHC-II) bone-marrow-derived macrophages as a source of surface-enzyme activity. After digestion supernatants were removed for analysis by HPLC to determine the effect of MHC haplotype on peptide degradation. Based on the reduction in peak area of uncleaved peptides obtained in three independent experiments, we deduced that incubation of peptides p14–33 and p381–394 with BALB.K macrophages led to reductions of 90% (± 3% SD) and 93% (± 3% SD), respectively, in the amount of full-length peptides present in supernatants (Fig. 2a,b). In contrast, incubation of peptides p14–33 and p381–394 with BALB/c macrophages led to reductions of 49% (± 4% SD) and 81% (± 5% SD), respectively. These data suggest that 42% (± 6% SD) less p14–33 and 15% (± 2% SD) less p381–394 was degraded by incubation with binding BALB/c macrophages, compared with non-binding BALB.K macrophages. Hence, protection of p14–33 at the macrophage surface by binding H-2d MHC-II molecules was significantly higher than that of p381–394 (P < 0·002).

Figure 2.

HPLC analysis of peptide digestion by fixed macrophages. Macrophages from BALB/c or BALB.K mice were fixed and incubated for 24 hr in serum-free HBSS at pH 7·2 with 80 μm peptide p14–33 (a), or p381–394 (b). As a control, peptides were incubated in the absence of macrophages (dashed line), which resulted in formation of at least three additional methionine oxidation products Met[O] from p381–394. The major peaks that differ between the presence and absence of macrophages are numbered 1–5. A representative of three experiments is shown. The proportion of full-length peptides protected from degradation by fixed MHC-matched BALB/c macrophages was calculated as 100% × (peak area for BALB/c supernatant − peak area for BALB.K supernatant)/peak area for peptide alone.

Fractions representing the major peaks shown in Fig. 2 were analysed by mass spectrometry revealing that digestion of peptides with non-binding BALB.K macrophages resulted in the generation of a larger number of detectable fragments, nine for p14–33 (Table 1) and 12 for p381–394 (Table 2), compared with the five and nine fragments released after incubation by binding BALB/c macrophages, respectively.22 The data suggest that additional cleavage sites were exposed in the peptide sequence of p14–33 and p381–394 upon incubation with non-binding H-2k MHC-II molecules.

Table 1.

Peptide p14–33 cleavage products generated on the cell surface of BALB.K and BALB/c macrophages

| Fragment | BALB.K macrophages* | BALB/c macrophages† |

|---|---|---|

| KEALDKYELENHDLKTKNEG‡ | KEALDKYELENHDLKTKNEG‡ | |

| 1 | KEALDKYELENHDLK----- | |

| 2 | KEALDKYELENHDL------ | |

| 3 | -EALDKYELENHDLKTKNEG | |

| 4 | --ALDKYELENHDLKTKNEG | |

| 5 | ---LDKYELENHDLKTKNEG | |

| 6 | ----DKYELENHDLKTKNEG | ----DKYELENHDLKTKNEG |

| 7 | ----DKYELENHDLK----- | ----DKYELENHDLK----- |

| 8 | ------YELENHDLKTKNE- | |

| 9 | ------YELENHDLKTKNEG | |

| 10 | -------ELENHDLKTKNEG | -------ELENHDLKTKNEG |

| 11 | -------ELENHDLK----- |

Nine fragments generated by incubation with BALB.K macrophages.

Five fragments generated by incubation with BALB/c macrophages.

Sequence of the full-length peptide p14–33 with the M517–31 T-cell epitope in italic.

Table 2.

Peptide p381–394 and its cleavage products generated on the cell surface of BALB.K and BALB/c macrophages

| Fragment | BALB.K macrophages* | BALB/c macrophages† |

|---|---|---|

| LIQEMLKTMESINQ‡ | LIQEMLKTMESINQ‡ | |

| 1 | LIQEMLKTME---- | |

| 2 | LIQEML-------- | |

| 3 | -IQEMLKTME---- | |

| 4 | -IQEMLKT------ | |

| 5 | --QEMLKTMES--- | |

| 6 | --QEMLKTM----- | |

| 7 | --QEMLK------- | --QEMLK------- |

| 8 | ---EMLKTME---- | |

| 9 | ----MLKTMESINQ | |

| 10 | ----MLKTMES--- | |

| 11 | ----MLKTM----- | |

| 12 | -----LKTMESINQ | -----LKTMESINQ |

| 13 | -----LKTMESIN- | |

| 14 | ------KTMESINQ | |

| 15 | -------TMESINQ | |

| 16 | -----LKTME---- | |

| 17 | ------KTMESI-- | |

| 18 | --------MESINQ | --------MESINQ |

Twelve fragments generated by incubation with BALB.K macrophages.

Nine fragments generated by incubation with BALB/c macrophages.

Sequence of the full-length peptide p381–394.

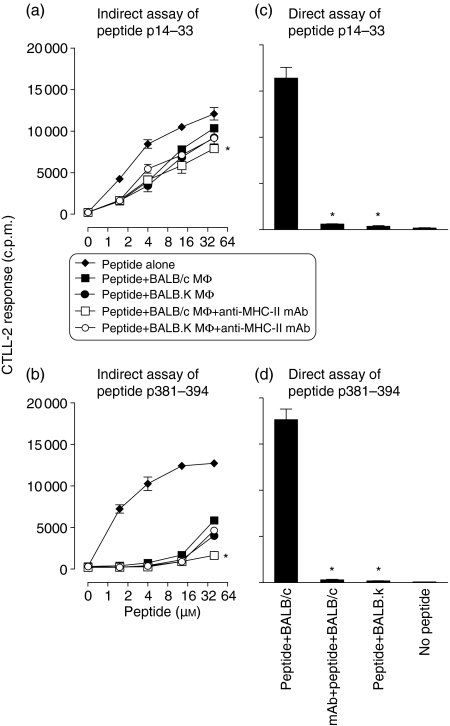

Anti-MHC class II antibody reverses rescue of exogenous peptides from degradation at the surface of macrophages

In the next experiments we addressed whether MHC-II-mediated rescue of exogenous peptides affects their presentation to T cells. Fixed BALB/c and BALB.K macrophages were incubated with peptides p14–33 or p381–394 for 24 hr before supernatants were removed and transferred to a separate plate of fixed BALB/c macrophages together with T-cell hybridomas specific for each peptide to assay for the presence of undegraded peptides. Under these experimental conditions, presentation of p14–33 and p381–394 by BALB/c macrophages was reduced by prior incubation with non-binding BALB.K macrophages compared with binding BALB/c macrophages (Fig. 3a,b). Based on the reduction in area under the curves, we deduced that incubation with binding BALB/c, compared with non-binding BALB.K macrophages resulted in 12% (± 7% SEM) reduction of p14–33 and 33% (± 10% SEM) reduction of p381–394 presentation.

Figure 3.

Direct and indirect peptide presentation at the cell surface of fixed macrophages. In the indirect assay, peptides p14–33 (a), or p381–394 (b) were incubated in the absence of fixed macrophages, in the presence of untreated fixed BALB/c or BALB.K macrophages, or of BALB/c and BALB.K macrophages treated with anti-MHC-II mAb before fixation and addition of peptides for 24 hr. Macrophage supernatants were transferred to fresh fixed BALB/c macrophages in the presence of enzyme inhibitors (see) to prevent further degradation and incubated for 24 hr before antigen presentation was assayed with specific T-cell hybridomas. As a control, the effect of anti-MHC-II mAb on the presentation of peptides p14–33 (c), or p381–394 (d) in direct assay is also shown. The difference between the level of peptide presentation by untreated BALB/c macrophages and those treated as described above was calculated by two-way anova, and significant differences are indicated by asterisks (P < 0·05). A representative of three experiments is shown.

In the next experiments, we tested whether anti-MHC-II mAb can reverse the rescue of exogenous peptides from degradation at the surface of macrophages. BALB/c macrophages were treated with anti-MHC-II mAb before fixation and incubation with peptides p14–33 or p381–394. Macrophage supernatants were transferred to a separate plate of fixed BALB/c macrophages, as above. Presentation of both peptides was significantly reduced by treatment with anti-MHC-II mAb, as compared with peptide presentation on untreated BALB/c macrophages (Fig. 3a,b). Anti-MHC-II mAb had no effect on peptide presentation after incubation with BALB.K macrophages (Fig. 3a,b). We also showed that anti-MHC-II mAb profoundly inhibited the presentation of peptides p14–33 and p381–394 in a direct presentation assay (Fig. 3c,d), whereas no presentation was observed by non-binding BALB.K macrophages (Fig. 3c,d), confirming H-2d restriction of peptide presentation. The data are consistent with mAb treatment interfering with peptide binding to Ad molecules on fixed macrophages, so that more peptide was degraded and hence not available for presentation in the subsequent T-hybridoma assay. Thus, H-2d MHC-II molecules may rescue a significant proportion of exogenous peptides from degradation at the macrophage surface.

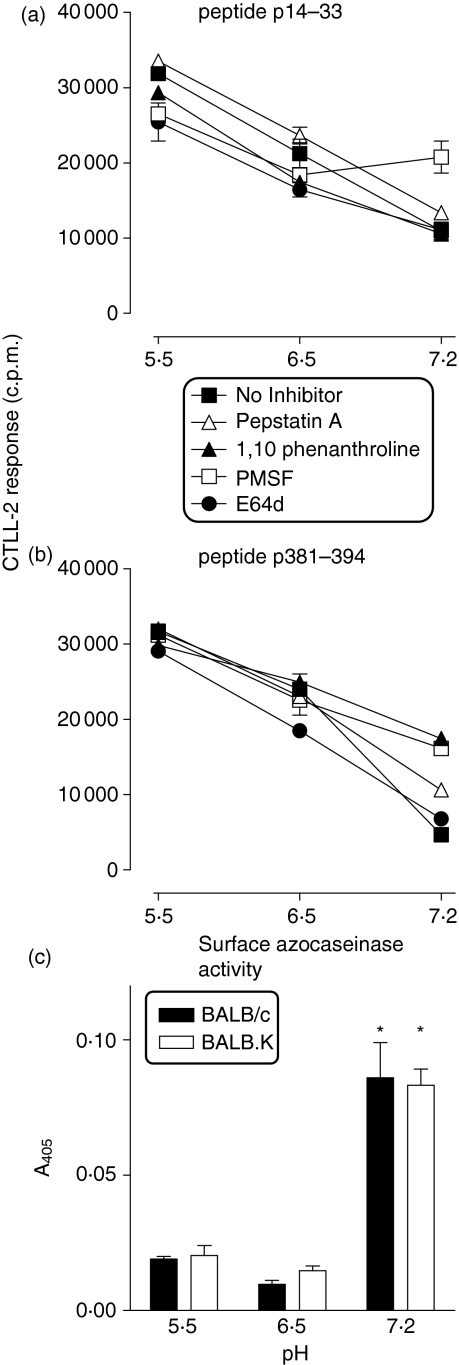

Peptide presentation by surface MHC-II molecules is pH-dependent

We studied the effect of extracellular pH on the equilibrium between peptide degradation and MHC-II-restricted presentation of exogenous peptides at the surface of fixed macrophages. The magnitude of presentation of exogenous peptides was greater at extracellular pH 5·5 than at pH 6·5 or 7·2 (Fig. 4a,b), which is consistent with the low pH optimum for peptide binding to MHC-II molecules.34 However, the up-regulatory effect of enzyme inhibitors on presentation of peptides p14–33 and p381–394 was observed at pH 7·2 but not at pH 5·5 and 6·5 (Fig. 4a,b), suggesting that degradation of peptides p14–33 and p381–394 by cell surface-associated enzymes was maximum at neutral pH. Consistent with our previous observations,22 presentation of p14–33 was enhanced at neutral pH in the presence of the serine proteinase inhibitor PMSF (Fig. 4a), while p381–394 presentation was increased by PMSF, the aspartic proteinase inhibitor pepstatin A and the metalloproteinase inhibitor 1,10 phenanthroline (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

The pH-dependency of peptide presentation by surface MHC-II. Pre-fixed macrophages were incubated in the absence or presence of enzyme inhibitors pepstatin A, 1,10 phenanthroline, PMSF, or E-64d before adding 40 μm synthetic peptides p14–33 (a), p381–394 (b) dissolved in serum-free HBSS pH 7·2 or 0·1 m sodium citrate buffers at pH 5·5 and 6·5. Lines indicate the relative amount of IL-2 secreted by specific T-cell hybridomas, measured as proliferation of CTLL-2 cells. Alternatively, fixed macrophages from BALB/c or BALB.K mice were incubated for 24 hr with 1% azocasein at pH 5·5, 6·5 and 7·2, and surface-associated proteolytic activity was measured at 405 nm, as described in (c). Bars indicate the relative level of the azocaseinase activity, with the background value (0·064 ± 006) subtracted from the test values. Asterisks denote the significant increase in the azocaseinase activity at pH 7·2 compared with pH 5·5 and pH 6·5, as calculated by two-way anova (P < 0·0001). The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

In control experiments, we used the azocasein assay to measure the overall protease activity of fixed macrophages from congenic BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.K (H-2k) mice, which confirmed that the cell-surface-associated enzyme activity was greatest at pH 7·2 (Fig. 4c). The data also show that the azocaseinase activities of fixed macrophages derived from both BALB/c and BALB.K mice were not significantly different (P > 0·3).

Discussion

We studied MHC-II-dependent rescue of exogenous H-2d-restricted peptides from proteolytic degradation by surface enzymes of macrophages used as APC for subsequent presentation to CD4 T cells. Both peptides were shown to bind directly to the surface of BALB/c (H-2d), but not BALB.K (H-2 k), macrophages and binding was inhibited by the presence of anti-Ad/Ed mAb, but not by anti-Kd or anti-CD1d mAb. This data strongly suggested that peptide binding to the surface of macrophages was mediated by the restricting Ad molecule. We also found evidence for peptide dissociation from MHC-II molecules expressed on the surface of binding BALB/c, but not BALB.K, macrophages, suggesting that short-lived peptide/MHC-II complexes are formed at the APC cell surface.

We investigated whether binding to H-2d molecules affected the degree of degradation of exogenous peptides at the surface of fixed BALB/c or BALB.K macrophages, respectively. Upon incubation of peptides with fixed macrophages, the supernatants were analysed by HPLC and mass spectrometry. This analysis showed a higher degree of peptide degradation in the presence of non-binding BALB.K macrophages, judged from: (1) the reduced HPLC peak area corresponding to the full-length peptides, (2) the increased number of peptide cleavage fragments, and (3) the appearance of the additional cleavage sites, confirming and extending previous observations made using purified MHC-II molecules in a cell-free system.20,21 We observed that protection from degradation of p14–33 at the macrophage surface was significantly higher than that of p381–394. This is consistent with our previously published data that p14–33 undergoes more limited degradation by serine proteinases at the cell surface, while at least three families of proteolytic enzymes are involved in the more complete degradation of p381–394.22 Thus, protection of peptides following binding to MHC molecules would be expected to vary from one peptide to another depending on their relative susceptibility to degradation in the extracellular space. Our data are consistent with an interpretation that peptide–MHC-II complexes at the surface of binding BALB/c, but not BALB.K, macrophages exist in an equilibrium, similar to the pH-dependent equilibrium of slow- and fast-dissociating peptide/MHC-II isomers which was proposed to be important for peptide exchange.35 We envisage that peptide exchange in the peptide-binding groove of MHC-II molecules expressed on the surface of BALB/c, but not BALB.K, macrophages accounts for the rescue of the extracellular peptides from degradation by surface proteinases.

The ability of surface MHC-II molecules to rescue peptides from degradation was confirmed in transfer experiments, in which peptides were first incubated with fixed BALB/c or BALB.K macrophages as a source of enzyme activity and then transferred to fresh fixed BALB/c macrophages as APC. Macrophages were also untreated or pretreated with anti-MHC-II mAb to directly assess the role of MHC molecules. We observed that presentation of p14–33 and p381–394 was significantly reduced when peptides were initially incubated with non-binding BALB.K macrophages compared with binding BALB/c macrophages, and that peptide presentation was further reduced when MHC-II molecules were treated with anti-MHC-II mAb. These data are consistent with the interpretation that MHC-II molecules bind exogenous peptides and protect them from proteolytic degradation by surface enzymes for presentation to CD4 T cells. We estimate that in our experimental system about 2–5 nmol peptide was rescued from degradation depending on the particular peptide, which clearly had a functional significance at the level of peptide presentation. Noteably, p14–33 and p381–394 were presented by Ed and Ad molecules, respectively, suggesting that the protective role is associated with both MHC-II molecules expressed on the cell surface of APC.

We have also shown that neutral extracellular pH down-regulates peptide presentation coincident with the maximum proteolytic activity of surface enzymes which cleave exogenous peptides. In particular, our previous report implicated various unidentified cell-surface serine-, aspartic- and metallo-proteinases in destructive processing of exogenous peptides.22 It should be noted that peptides already bound to MHC-II molecules could be subjected to further sequential N-terminal truncation by cell-surface enzymes, such as aminopeptidase N (CD13), leading to enhanced or decreased presentation of peptides depending on the particular epitope.17,36 It has also been shown that other factors, such as surface expression of DM chaperone, down-regulate the formation of peptide/MHC-II complexes on the cell surface and antigen presentation.14 Exogenous peptides bound to MHC-II molecules are directly presented to CD4 Th2-type T cells, as reported recently.37 However, our earlier data suggest that some peptide fragments (natural peptide ligands) produced by surface enzymes compete for binding of the full-length peptide to surface MHC-II molecules and prevent presentation to T cells.22

This study extends our understanding of the ‘on-surface’ MHC-II antigen presentation pathway. In this pathway, exogenous peptides bearing CD4 T cell epitopes bind to empty MHC-II molecules expressed on the cell-surface of APC for presentation to CD4 T cells.38 Peptide presentation by MHC-II molecules has been shown to be up-regulated by acid pH, possibly as a result of the reversible pH-dependent conformational change of MHC-II molecules34 and/or the nanostructure of peptides themselves.39,40 Our report provides evidence that a low pH environment enhances presentation of exogenous peptides by surface MHC-II molecules also by inhibiting the destructive enzyme activity associated with the cell surface. This finding suggests that the peptide-loading capacity of MHC-II molecules could be selectively enhanced at inflammatory sites characterized by low pH.41 This situation would allow different APC to bind peptides generated from self and non-self proteins in normal tissues or sites of inflammation for direct presentation to specific T cells, which could be important for mounting immune responses and maintaining peripheral tolerance.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grant 058930/Z/99/Z from The Wellcome Trust and by grant 96/B1/S/02407 from the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- c.p.m.

counts per minute

- E-64d

(2S,3S)-trans-epoxysuccinyl-l-leucylamido-3-methyl-butane

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HBSS

Hanks' balanced salt solution

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IL-2

interleukin-2

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MHC-II

major histocompatibility complex class II

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride

- SipC

Salmonella invasion protein C

References

- 1.Unanue ER. Perspective on antigen processing and presentation. Immunol Rev. 2002;185:86–102. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18510.x. 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Thery C, Amigorena S. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:621–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts C. The exogenous pathway for antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II and CD1 molecules. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:685–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1088. 10.1038/ni1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindner R, Unanue ER. Distinct antigen MHC class II complexes generated by separate processing pathways. EMBO J. 1996;15:6910–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimonkevitz R, Kappler J, Marrack P, Grey HM. Antigen recognition by H-2-restricted T cells. I. Cell-free antigen processing. J Exp Med. 1983;158:303–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.2.303. 10.1084/jem.158.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen PE. Reduction of disulfide bonds during antigen processing: evidence from a thiol-dependent insulin determinant. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1121–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1121. 10.1084/jem.174.5.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quin SJ, Seixas EM, Cross CA, Berg M, Lindo V, Stockinger B, Langhorne J. Low CD4+ T cell responses to the C-terminal region of the malaria merozoite surface protein-1 may be attributed to processing within distinct MHC class II pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:72–81. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<72::aid-immu72>3.0.co;2-z. 10.1002/1521-4141(200101)31:1<72::AID-IMMU72>3.3.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen PE. Acidification and disulfide reduction can be sufficient to allow intact proteins to bind class II MHC. J Immunol. 1993;150:3347–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrasco-Marín E, Paz-Miguel JE, López-Mato P, Alvarez-Domínguez C, Leyva-Cobián P. Oxidation of defined antigens allows protein unfolding and increases both proteolytic processing and exposes peptide epitopes which are recognized by specific T cells. Immunology. 1998;95:314–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vergelli M, Pinet VM, Vogt AB, Kalbus M, Malnati MS, Riccio P, Long EO, Martin R. HLA-DR-restricted presentation of purified myelin basic protein is independent of intracellular processing. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:941–51. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson JH, Delvig AA. Diversity in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunology. 2002;105:252–62. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01358.x. 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee P, Matsueda GR, Allen PM. T cell recognition of fibrinogen. A determinant on the Aα-chain does not require processing. J Immunol. 1988;140:1063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colledge L, Sun MY, Lin W, Blackburn CC, Reay PA. Differing processing requirements of four recombinant antigens containing a single defined T-cell epitope for presentation by major histocompatibility complex class II. Immunology. 2001;103:343–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arndt SO, Vogt A, Marcovic-Plese S, et al. Functional HLA-DM on the surface of B cells and immature dendritic cells. EMBO J. 2000;19:1241–51. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1241. 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman MA, Weber DA, Spotts EA, Moore JC, Jensen PE. Inefficient peptide binding by cell-surface class II MHC molecules. Cell Immunol. 1997;182:1–11. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1219. 10.1006/cimm.1997.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackman MJ, Holder AA. Secondary processing of the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 (MSP1) by a calcium-dependent membrane-bound serine protease: shedding of MSP133 as a noncovalently associated complex with other fragments of the MSP1. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;50:307–15. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90228-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larsen SL, Pedersen LØ, Buus S, Stryhn AJ. T cell responses affected by aminopeptidase N (CD13)-mediated trimming of major histocompatibility complex class II-bound peptides. J Exp Med. 1996;184:183–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.1.183. 10.1084/jem.184.1.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen AS, Noren O, Sjöström H, Werdelin O. A mouse aminopeptidase N is a marker for antigen-presenting cells and appears to be co-expressed with major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2358–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ansorge S, Scho E, Kunz D. Membrane-bound peptidases of lymphocytes: functional implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;50:799–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouritsen S, Meldal M, Werdelin O, Hansen AS, Buus S. MHC molecules protect T cell epitopes against proteolytic destruction. J Immunol. 1992;149:1987–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donermeyer DL, Allen PM. Binding to Ia protects an immunogenic peptide from proteolytic degradation. J Immunol. 1989;142:1063–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Delwig A, Musson JA, McKie N, Gray J, Robinson JH. Regulation of peptide presentation by major histocompatibility complex class II molecules at the surface of macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3359–66. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324461. 10.1002/eji.200324461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JH, Case MC, Kehoe MA. Characterization of a conserved helper-T-cell epitope from group A streptococcal M proteins. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1062–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.3.1062-1068.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson JH, Atherton MC, Goodacre JA, Pinkney M, Weightman H, Kehoe MA. Mapping T-cell epitopes in group A streptococcal type 5 M protein. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4324–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4324-4331.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musson JA, Hayward RD, Delvig AA, Hormaeche CE, Koronakis V, Robinson JH. Processing of viable Salmonella typhimurium for presentation of a CD4 T cell epitope from the Salmonella invasion protein C (SipC) Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2664–71. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200209)32:9<2664::AID-IMMU2664>3.0.CO;2-N. 10.1002/1521-4141(200209)32:9<2664::AID-IMMU2664>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer HG, Opel B, Reske K, Reske-Kunz AB. Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages reveal accessory cell function and synthesis of MHC class II determinants in the absence of external stimuli. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1151–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musson JA, Walker N, Flick-Smith HC, Williamson ED, Robinson JH. Differential processing of CD4 T-cell epitopes from the protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52425–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309034200. 10.1074/jbc.M309034200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delvig AA, Robinson JH. Different endosomal proteolysis requirements for antigen processing of two T-cell epitopes of the M5 protein from viable Streptococcus pyogenes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3291–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3291. 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandez-Borja M, Verwoerd D, Sanderson F, Aerts H, Trowsdale J, Tulp A, Neefjes JJ. HLA-DM and MHC class II molecules co-distribute with peptidase-containing lysosomal subcompartments. Int Immunol. 1996;8:625–40. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.5.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamai M, Matsumoto K, Omura S, Koyama I, Ozawa Y, Hanada K. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of cysteine proteinases by EST, a new analogue of E-64. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1986;9:672–7. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.9.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puri J, Factorovich Y. Selective inhibition of antigen presentation to cloned T cells by protease inhibitors. J Immunol. 1988;141:3313–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi H, Cease KB, Berzofsky JA. Identification of proteases that process distinct epitopes on the same protein. J Immunol. 1989;142:2221–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rowan AD, Buttle DJ. Pineapple cysteine endopeptidases. Meth Enzymol. 1994;244:555–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jensen PE, Weber DA, Thayer WP, Westerman LE, Dao CT. Peptide exchange in MHC molecules. Immunol Rev. 1999;172:299–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt L, Boniface JJ, Davis MM, McConnell HM. Kinetic isomers of a class II MHC–peptide complex. Biochem. 1998;37:17371–80. doi: 10.1021/bi9815593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buus S, Werdelin O. Oligopeptide antigens of the angiotensin lineage compete for presentation by paraformaldehyde-treated accessory cells to T cells. J Immunol. 1986;136:459–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buatois V, Baillet M, Bécart S, Mooney N, Leserman L, Machy P. MHC class II–peptide complexes in dendritic cell lipid microdomains initiate the CD4 Th1 phenotype. J Immunol. 2003;171:5812–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vacchino JF, McConnell HM. Peptide binding to active class II MHC protein on the cell surface. J Immunol. 2001;166:6680–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong Y, Legge RL, Zhang S, Chen P. Effect of amino acid sequence and pH on nanofiber formation of self-assembling peptides EAK16-II and EAK16-IV. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1433–42. doi: 10.1021/bm0341374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadegh-Nasseri S, Stern LJ, Wiley DC, Germain RN. MHC class II function preserved by low-affinity peptide interactions preceding stable binding. Nature. 1994;370:647–50. doi: 10.1038/370647a0. 10.1038/370647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindahl O. Pain: a chemical explanation. Acta Rheumatol Scand. 1962;8:161–9. doi: 10.3109/rhe1.1962.8.issue-1-4.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]