Abstract

In this report, we describe 12 subpopulations of porcine γδ thymocytes based on their expression of CD1, CD2, CD4, CD8-isoforms and CD45RC. Our data suggest that γδ thymocytes can be divided into two major families: (a) one large family of CD4− γδ thymocytes that could be further subdivided according to the CD2/CD8αα phenotype and (b) a small family of CD4+ γδ thymocytes bearing CD8αβ and possessing certain unusual features in comparison with other γδ thymocytes. Maturation of γδ thymocytes within the CD4− family begins with proliferation of the CD2+ CD8− CD1+ CD45RC− γδ common precursor. This developmental stage is followed by diversification into the CD2+ CD8αα+, CD2+ CD8− and CD2− CD8− subsets. Their further maturation is accompanied by a loss of expression of CD1 and by increased expression of CD45RC. Therefore, individual subsets develop from CD1+ CD45RC− through CD1− CD45RC− into CD1− CD45RC+ cells. On the other hand, γδ thymocytes within the CD4+ family bear exclusively CD8αβ, always express CD1, but may coexpress CD45RC. These cells have no counterpart in the periphery. Our observations suggest that all peripheral CD8+ γδ T cells express CD8αα and that two subsets of these cells differing in major histocompatibility complex II expression, occur. We propose that one subset acquires CD8αα in the thymus while the second acquires CD8αα as a result of stimulation in the periphery.

Keywords: γδ T cells; thymus; T-cell receptor (TCR); cell development/ differentiation; animal models/studies: cows, pigs, horses, cats, dogs

Introduction

Two types of CD3-associated T-cell receptor (TCR) molecules have been identified in all vertebrate studied consisting of either a TCRαβ or TCRγδ heterodimer.1 In extensively studied species like human, mouse and rat, TCRαβ is expressed on >95% of all T cells in both thymus and peripheral lymphoid sites while TCRγδ+ cells constitute a minor subset. Unlike rodents and humans, pigs, ruminants and chickens have a higher proportion of γδ T cells in the peripheral blood and lymphoid organs (reviewed in 2). In these species, γδ T cells may account for half of the peripheral T-cell pool.

Although the exact physiological role, specificity and function of γδ T cells is not fully known in any species, their ontogeny, phenotype, distribution and repertoire has been studied in some species, partially including swine. Similar to mice3 and chickens4 porcine TCRγδ+ cells are the earliest detectable T-cell subset, developing in the thymus and subsequently populating the periphery.5,6 They appear to require a shorter time period for maturation than αβ T-cells and can develop without any CD3εlo or TCRγδlo transitional stage.5,6 Peripheral γδ T cells in swine are subdivided into three subsets based upon their expression of CD2 and CD8 and include CD2− CD8−, CD2+ CD8− and CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ T lymphocytes.5,7,8 These individual subsets differ in their homing characteristic: CD2+ CD8αα+ and CD2+ CD8− γδ T cells preferentially accumulate in the spleen while CD2− CD8− are enriched in the circulation.5,7,8 The same phenotype-dependent pattern of tissue distribution has not been identified in mice or humans although CD2+ CD8− γδ T cells as well as γδ T cells expressing CD8 or lacking CD2 molecules have been observed and mucosal γδ T cells show distinctive TCRγδ gene usage and phenotype that distinguishes them from the peripheral blood pool. The porcine CD2+ CD8αα+ subset has been postulated to be the progeny of peripheral CD2+ CD8− γδ T lymphocytes. This is based on the observation that: (a) some TCRγδ+ CD8− cells may acquire CD8 upon activation9 (b) that CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ T cells are potentially cytotoxic while other TCRγδ+ cell subsets are not10,11 and (c) CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ T cells are scarce in porcine fetuses.5 In contrast to peripheral γδ T cells, the majority of γδ thymocytes express CD2 and like peripheral γδ T cells, γδ thymocytes can be separated into the same three subsets based on CD2/CD8 expression.5,6,8 In contrast to mice, a minor subpopulation of porcine thymic γδ T cells expresses CD4 together with CD8.6,8,10 A large number of porcine γδ thymocytes have been shown to be actively proliferating, which may explain their prominence in porcine peripheral blood.6

In this study, we have used flow cytometry to examine porcine thymic γδ T cells with regards to their expression of CD1, CD2, CD4, CD8αα, CD8αβ, CD45RC and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (SLA-DR). We show that CD1 and CD45RC expression on porcine γδ thymocytes define subpopulations with developmentally dependent changes in their phenotype. Our findings also suggest that maturation of γδ thymocytes occurs after the expression of TCRγδ, that all TCRγδ+ T-cell subsets may develop in the thymus and that expression of CD2 and/or CD8 are not useful differentiation markers.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animals used in the study were: (a) derived from Minnesota miniature pigs by repeated crossing with outbred black Vietnam-Asian and white Malaysian-derived pigs (breeding in Novy Hradek); (b) White PIC/Camborough crossbred gilts; and (c) Large White/Landrace (BUxL) crossbred gilts.12,13 All sows were healthy and normal at slaughter. Fetuses of different age were obtained by hysterectomy. Gestation age was calculated from the day of mating. Gestation in swine is 114 days. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institute of Microbiology, Czech Academy of Science, according to guidelines in the Animal Protection Act.

Preparation of cell suspensions

Cell suspensions from thymus and spleen were prepared in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by carefully teasing the tissues using a forceps and then by passage through a 70 µm mesh nylon membrane. All cell suspensions were washed twice in cold PBS containing 0·1% sodium azide and 0·2% gelatin (PBS-GEL). Heparinized (20 U/ml) blood was obtained by umbilical (fetuses) or intracardial puncture (adult animals). Erythrocytes and most erythroblasts were removed from the pelleted cells and whole blood using hypotonic lysis.5,6 Cell suspensions were finally washed twice in cold PBS-GEL, filtered through a 70 μm mesh nylon membranes and cell numbers determined by haemocytometer.

Immunoreagents

The following mouse anti-pig monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were used as primary immunoreagents: anti-CD1 (76-7-4, immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a)), anti-CD2 (MSA4, IgG2a or 1038H-5-37, IgM), anti-CD3ε (PPT3, IgG1 or PPT6, IgG2b), anti-TCRγδ (PPT17, IgG1 or PPT16, IgG2b), anti-CD4 (10·2H2, IgG2b), anti-CD8 (76-2-11, IgG2a), anti-CD8β (PPT23, IgG1), anti-CD45RC (MIL5, IgG1) and anti-SLA-DR (MSA3, IgG2a, MHC class II type antigen). All mAbs were gifts from following researchers: Dr H. Yang (Institute of Animal Health, Pirbright, UK), Dr J. K. Lunney (Animal Parasitology Institute, Beltsville, MD), Dr M. D. Pescovitz (Indiana University, IN) and Dr C. R. Stokes (University of Bristol, Bristol, UK). The specificity of these mAbs has been described previously.5,6 Anti-CD2, anti-TCRγδ, anti-CD4, anti-CD8 and anti-CD45RC mAb were labelled with biotin N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Vector Laboratories, Burlinghame, CA) according to a protocol recommended by the manufacturer.

Goat polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) specific for mouse immunoglobulin subclasses (Southern Biotechnologies Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL) labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), R-phycoerythrin (RPE) or Cy5 were used as secondary immunoreagents. Biotinylated primary antibodies were detected by a streptavidin-SpectralRed (St-SPRD) conjugate (Southern Biotechnologies Associates, Inc).

All immunoreagents were titrated to provide the optimal signal : noise ratio. Isotype-matched mouse anti-rat monoclonal antibodies were used as negative controls.

Staining of cells

Staining of cells for flow cytometry analysis (FCM) and sorting was performed as described previously.5,6 Briefly, multicolour staining was done using cells that had been incubated with a combination of two (two-colour staining), three (three-colour staining) or four (four-colour staining) primary mouse mAbs of different subisotypes. In the case of staining with SPRD dye, one of the mAbs was labelled with biotin. Cells were incubated for 30 min and subsequently washed twice. Mixtures of goat secondary pAbs specific for mouse immunoglobulin subclasses that had been labelled with FITC, RPE or Cy5 and St-SPRD conjugate were then added to the cell pellets in appropriate combinations. After 30 min, cells were washed three times and analysed by flow cytometry (FCM). In the case of subisotype-matched mAb, staining involved cells stained with mAbs of different subisotypes that were detected by secondary pAb labelled with FITC, RPE or Cy5. These cells were later incubated for 10 min with PBS-GEL containing 10% heat-inactivated normal mouse serum to block the free binding sites of the previously bound secondary pAb. After washing, the cells were incubated for 30 min with a biotinylated subisotype-matched primary mAb for 30 min and subsequently washed twice. Finally, St-SPRD was added for 30 min and the cells were then washed three times prior to FCM analysis.

The DNA content of multicolour-stained cells was determined using the DNA intercalating probe 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD). Surface stained cells were washed in cold PBS containing 0·1% sodium azide (PBS-Az), centrifuged and fixed with cold (−20°) 70% ethanol for 1 hr at 4°, centrifuged again (2000 g, 10 min, 4°) and washed in PBS-Az. The pellets were then incubated with 50 µl of 7-AAD in PBS-Az (40 µg/ml) for at least 20 min at 4° in dark until measured using FCM.

Flow cytometry

Samples were measured and/or sorted on a FACSort, FACSCalibur or FACSVantage flow cytometers (all instruments BDIS, Mountain View, CA). 50 000–1 000 000 events were collected in each measurement. Electronic compensation was used to eliminate residual spectral overlaps between individual fluorochromes in multicolour staining experiments. Damaged and dead cells were excluded from analysis using propidium iodide fluorescence. A FACSort Doublet Discrimination Module was used for DNA content analysis that allowed single cell events to be discriminated from doublets and higher multiplets.

Statistical analysis

Difference among the median frequency values for γδ thymocytes and their subsets during prenatal and postnatal ontogeny were analysed by one way analysis of variance (anova) – Student–Newman–Keuls test. The level of statistical significance is reported in P-values. The strength of association between the age of the animals and the frequencies of γδ thymocytes and their subsets was measured using Pearson product moment correlation and level of statistical significance (P-value) for particular correlation coefficient (CC) is reported.

Results

Three subsets of porcine γδ thymocytes exist based upon expression of CD2 and CD8

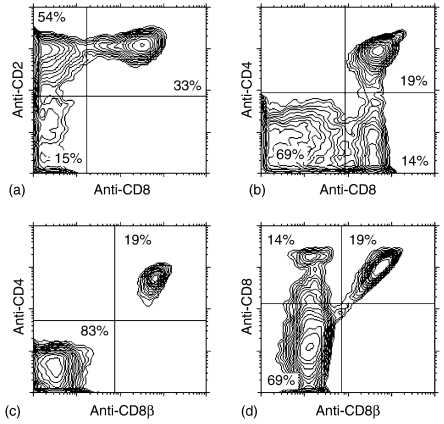

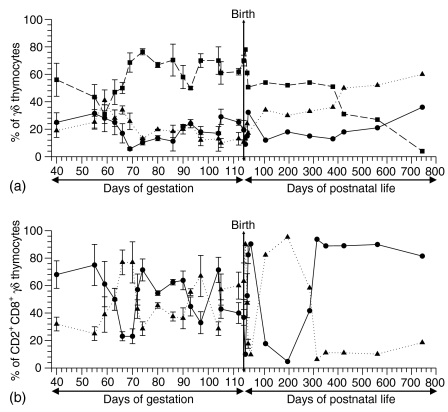

In agreement with earlier published results5,8 analysis of TCRγδ+ thymocytes showed they could be subdivided into CD2− CD8−, CD2+ CD8− and CD2+ CD8+ subsets Fig. 1a). We were unable to detect any thymocytes expressing CD8 without CD2 at any age in the animals studied. Screening of these three TCRγδ+ thymocyte subsets during ontogeny showed that the majority of TCRγδ+ thymocytes were mostly CD2+ CD8− (P < 0·0001) while the minority comprised approximately equal numbers of CD2− CD8− or CD2+ CD8+ thymocytes (Fig. 2a). The only exceptions were found at midgestation (about day of gestation (DG)50–DG60) and in pigs older then 1 year. Especially in the latter case, the proportion of CD2+ CD8− γδ thymocytes decreased as the proportion of CD2− CD8− and CD2+ CD8+ γδ thymocytes increased (Fig. 2a) in the time dependent manner (CC > 0·92 at P < 0·02).

Figure 1.

Representative three-colour FCM analysis of CD2, CD4, pan-CD8, and CD8β expression by TCRγδ+ thymocytes isolated from a 9-month-old pig. Live (propidium iodide negative) TCRγδ+ thymocytes were gated and analyzed for expression of following cell surface antigens: CD2/pan-CD8 (a), CD4/pan-CD8 (b), CD4/CD8β (c), and pan-CD8/CD8β (d).These findings were confirmed in all experiments regardless age and breed of animals. Indicated values in dot plots represent the percentages of TCRγδ+ thymocytes.

Figure 2.

(a)Analysis of CD2− CD8− (circles, solid line), CD2+ CD8− (squares, dashed line) and CD2+ CD8+ (triangles, dotted line) γδ thymocytes during prenatal and postnatal ontogeny. The proportion of individual subsets is expressed as a percentage of total TCRγδ+ thymocytes. (b) Analysis of CD4− CD8αα+ (circles, solid line) and CD4+ CD8αβ+ (triangles, dotted line) γδ thymocytes during prenatal and postnatal ontogeny. The proportion of individual subsets is expressed as a percentage of total CD2+CD8+TCRγδ+ thymocytes. In both graphs, data points for fetal and neonatal pigs represent average values and error bars represent the mean ± SEM obtained at least from three animals for each gestation stage. Data points for pigs after birth represent actual values obtained from one animal. The time of birth is indicated by the vertical line across the graph.

Subpopulation of CD4+ CD8+ γδ thymocytes expresses the CD8αβ-heterodimer while all CD4− CD8+ γδ thymocytes express the CD8αα-homodimer

We did not detect porcine γδ thymocytes that expressed only CD4 but some TCRγδ+ thymocytes were double positive (DP) for CD4 and CD8 (Fig. 1b). According to the finding that there were no CD2− CD8+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1a), CD8+ γδ thymocytes could be further subdivided into two subsets on the basis of CD4 expression: CD2+ CD4−CD8+ (Fig. 1b, lower right quadrant) and CD2+ CD4+ CD8+ cells (Fig. 1b, upper right quadrant). The subpopulation of CD4+ CD8+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1b) resembles the DP thymocytes of the αβ T-cell lineage.6 We therefore investigated whether this subset also expressed the CD8αβ-heterodimer because all known peripheral CD8+ γδ T lymphocytes express the CD8αα-homodimer,10 and are CD4 negative.5,8 Fig. 1(c) showed that all CD4+ γδ thymocytes were CD8αβ+. Moreover, when mAb recognizing all CD8 isoforms (pan-CD8) and mAb recognizing only the CD8β-heterodimer were used (Fig. 1d), the number of CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1d, upper right quadrant) equalled the number of CD4+ CD8αβ+ (Fig. 1c, upper right quadrant) or CD4+ CD8+ (Fig. 1b, upper right quadrant) γδ thymocytes. On the other hand, the number of CD8αα+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1d, upper left quadrant) corresponded to the number of CD4− CD8+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1b, lower right quadrant). These findings were confirmed in all experiments regardless of the age or breed of the animals. Therefore the CD8αβ-heterodimer was only expressed by γδ thymocytes of the CD4+ CD8+ subset. In summary, four subpopulations of thymic γδ T cells exist as regards expression of CD2, CD4 and CD8-isoforms: CD2− CD4− CD8−, CD2+ CD4− CD8−, CD2+ CD4− CD8αα+ and CD2+ CD4+ CD8αβ+. Analysis of CD8+ γδ thymocyte subsets (CD2+ CD4− CD8αα+ and CD2+ CD4+ CD8αβ+) during ontogeny showed that their proportions fluctuate independently of age, with exception of pigs older than 1 year in which the proportion of CD2+ CD4− CD8αα+ γδ thymocytes dominated (P < 0·0003, Fig. 2b).

Characterization of CD1 and CD45RC expression by TCRγδ+ thymocytes results in the identification of additional subsets of CD2/CD8-based phenotyping

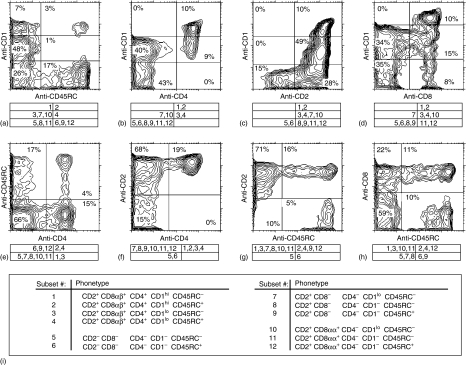

Triple-colour FCM analysis allowed γδ thymocytes defined by CD2/CD8/CD4 expression to be further subdivided into 12 subsets on the basis of their CD1 and CD45RC expression (Fig. 3i). CD1hi γδ thymocytes were always CD4+ (Fig. 3b), CD2+ (Fig. 3c) and CD8+ (Fig. 3d). Because CD4 is expressed only on CD2+ CD8αβ+ CD4+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 1b–d and Fig. 3f) and CD1hi γδ thymocytes could be either CD45RC− or CD45RC+ (Fig. 1a), we could divide the CD1hi γδ thymocytes into subset #1 and #2 (Fig. 3i).

Figure 3.

Representative three-colour FCM analysis of CD1, CD2, CD4, pan-CD8, and CD45RC expression by TCRγδ+ thymocytes isolated from a 9-month-old pig. Live (propidium iodide negative) TCRγδ+ thymocytes were gated and analysed for expression of the following cell surface antigens: CD1/CD45RC (a), CD1/CD4 (b), CD1/CD2 (c), CD1/CD8 (d), CD45RC/CD4 (e), CD2/CD4 (f), CD2/CD45RC (g), and CD8/CD45RC (h). Twelve principal γδ thymocyte subsets (subset 1–12) were found and their phenotype is indicated in the table at the bottom (i). The contribution of individual γδ thymocyte subsets to each quadrant is indicated under particular dot plots. Indicated values in dot plots represent the percentages of TCRγδ+ thymocytes.

The CD4+ γδ thymocytes (and therefore also CD2+ CD8αβ+ Fig. 1b–d and Fig. 3f) were always CD1+ but both CD1hi (subset #1 and #2) and CD1lo expression could be identified (Fig. 3b). Because CD4+ CD45RC+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3e) were always more frequent than CD1hi CD45RC+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3a), not all CD4+ CD45RC+ γδ thymocytes are CD1hi and not all CD4+ CD1lo γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3b) are CD1loD45RC+ (Fig. 3a). Therefore, subset #3 as well as subset #4 were always present (Fig. 3i). Regardless of animal age or breed, we found that the frequency of subset #4 corresponded with the frequency of CD1l°D45RC+ γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3a). Thus, the CD1l°D45RC+ γδ thymocytes must be solely composed of subset #4 (Fig. 3a).

CD2− γδ thymocytes constituted only one subpopulation as regards CD2/CD8/CD4 expression and these were CD2− CD8− CD4− (Fig. 1a, b). Because CD2− γδ thymocytes were: (a) always CD1− (Fig. 3c) and (b) either CD45RC− or CD45RC+ (Fig. 3g), the CD2− CD8− CD4− subpopulation of γδ thymocytes could be further subdivided only into subset #5 and #6 (Fig. 3i).

The remaining two subpopulations of γδ thymocytes that were classified on the basis of CD2/CD8/CD4 expression were either CD2+ CD8− CD4− or CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4− (Fig. 1). Because these two subpopulations are always CD4− and the frequency of CD2− CD1− γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3c) never reached the frequency of either CD4− CD1− or CD4− CD1lo γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3b), CD2+ CD8− CD4− or CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4− could be either CD1 negative or could express CD1 at low density. As mentioned above, all CD1lo γδ thymocytes expressing CD45RC (Fig. 3a) belong to subset #4 and were CD4+. For this reason, as well as the absence of CD1lo expression on CD2− CD8− CD4− γδ thymocytes (subsets #5 and #6), CD2+ CD8− CD4− and CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4− γδ thymocytes expressing CD1lo must be CD45RC− and were therefore classified as subset #7 and #10, respectively (Fig. 3i). Furthermore, CD4+ γδ thymocytes could not be CD1− (Fig. 3b) so that all CD2+ CD1− γδ thymocytes (Fig. 3c) were either CD2+ CD8− CD4− or CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4−. Using a similar means of discrimination, all CD8+ CD1− γδ thymic cells (Fig. 3d) were CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4−. Comparing these findings with the frequency of γδ thymocytes that were CD1− CD45RC+/− (Fig. 3a), CD8+/− CD45RC+/− (Fig. 3h), CD4− CD45RC+/− (Fig. 3e) and CD2+ CD45RC+/− (Fig. 3g) indicated that both CD2+ CD8− CD4− CD1− and CD2+ CD8αα+ CD4− CD1− γδ thymocytes could also be CD45RC− as well as CD45RC+ and may be divided into subsets #8 to #9 and subsets #11 to #12, respectively.

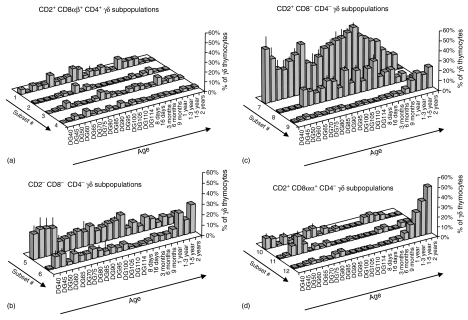

Analysis of CD1, CD2, CD4, CD8 and CD45RC expression during ontogeny indicates that CD1/CD45RC expression but not CD2/CD8 expression, define a developmental pathway for γδ thymocytes

Analysis of different thymic TCRγδ+ subpopulations in terms of CD2, CD8, CD4, CD1, and CD45RC expression during prenatal and postnatal ontogeny (Fig. 4) showed that the majority of γδ thymocytes generally represented subset #7 though its proportion generally decline with age (CC < −0·77 at P < 1 × 10−5). This subset reached its highest frequency very early in gestation and again near parturition. The frequency of occurrence of subset #5 and subset #8 (after DG60) also tended to decrease with age, especially in postnatal animals (CC < −0·56 at P < 0·005). On the other hand, subset #6, #9 and #12 were observed less frequently during fetal ontogeny but their contribution to the total γδ thymocyte pool increased postnatally and was sharply elevated in older animals (CC > +0·64 at P < 0·005). Changes in the proportion of some γδ thymocyte subsets, including subset #1, #2, #3, #4, #10 and #11, did not show an apparent trend with respect to animal age and remained relatively constant during ontogeny. Because our observations indicated that the CD4+ γδ thymocytes (subsets #1 to #4) behaved unusually (see bellow), we focused on the remaining CD4− γδ thymic cells (subsets #5 to #12, Fig. 4b–d). These showed a specific ontogenetic profile with regard to the expression of CD1 and CD45RC but not with regards to CD2 and CD8 expression. Particularly, the proportion of all CD1lo D45RC− (subsets #7 and #10) and CD1−CD45RC− γδ thymocytes (subsets #5, #8 and #11) decreased with age (CC < −0·80 at P < 1 × 10−6 and CC < −0·71 at P < 1 × 10−4, respectively) as the frequency of the CD1− CD45RC+ γδ thymocytes (subsets #6, #9 and #12) increased (CC > +0·92 at P < 1 × 10−10). This ontogenetic profile of γδ thymocyte subsets allowed us to propose a model for development of porcine γδ thymocytes (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

The frequencies of γδ thymocyte subsets phenotypized using FCM, according to expression of CD1, CD2, CD4, pan-CD8, CD8β, and CD45RC during different time points of prenatal and postnatal ontogeny. Twelve principal γδ thymocyte subsets (numbered 1–12 on the z-axis) were found and their number, designation and phenotype are carried out in the same manner as in Fig. 3 and in the text: Subsets #1 to #4 inside of CD2+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes are shown in (a), subsets #5 to #6 inside of CD2− CD8− γδ thymocytes are shown in (b), subsets #7 to #9 inside of CD2+ CD8− γδ thymocytes are shown in (c) and subsets #10 to #12 inside of CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ thymocytes are shown in (d). Only live (propidium iodide negative) γδ thymocytes were analysed and the proportion of individual subsets (y-axis) is expressed as a percentage of all γδ thymocytes. ‘DG’ stands for day of gestation and ‘days’, ‘months’ and ‘years’ refer to age of postnatal life (x-axis). Individual bars for fetal and neonatal pigs represent average values and error bars represent the mean ± SEM obtained at least from three animals for each gestation stage. Data points for pigs after birth represent actual values obtained from one animal.

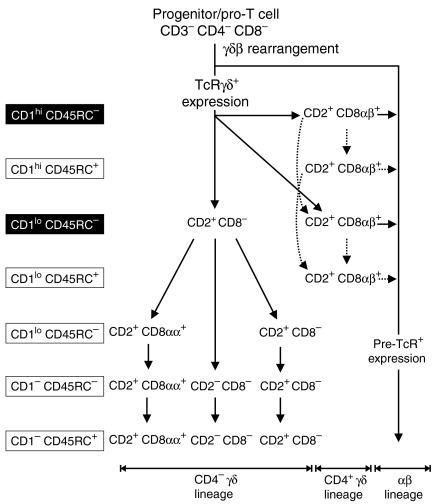

Figure 5.

Proposed model of γδ T-cell development in porcine thymus. We suggest two major pathways of γδ thymocyte development: (a) the CD2+ CD4− CD8− precursor pathway (CD4− γδ lineage, see bottom line) leading to the development of all TCRγδ+ subset that bear the CD2/CD8αα phenotype; and (b) the CD2+ CD4+ CD8αβ+ precursor pathway (CD4+ γδ lineage, see bottom line) that contains TCRγδ+ thymocytes presumably extinguishing their TCRγδ expression, become DP thymocytes and follow the differentiation pathway of the αβ T-cell lineage. The phenotype of individual subsets is given. Individual developmental stages determined using CD1 and CD45RC expression are summarized on the left: black boxes for CD1/CD45RC phenotype represent large dividing γδ thymocytes while open boxes represent small non-dividing γδ thymic cells. Solid arrow lines represent major pathways of development while dotted arrow lines represent alternative pathways of development.

The majority of peripheral γδ T cells are CD1− CD4− CD8β− CD45RC+ while γδ thymocytes are more complex

Analysis of CD1, CD2, CD4, CD8, CD8β, CD45RC and SLA-DR (MHC-II) expression on peripheral γδ T cells (Fig. 6, columns I–II and IV–V) in comparison with γδ thymocytes (Fig. 6, columns III and VI) revealed that γδ lymphocytes isolated from the blood and spleen were uniformly CD1− (Fig. 6a, b, d, e), CD4− (Fig. 6g, h, j, k), and CD8β− (Fig. 6g, h, j, k), irrespective of animal age. We were also unable to detect expression of CD1, CD4 and/or CD8β on γδ T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes, Peyer's patches, intraepithelial lymphocytes, liver, tonsils, stomach, skin, lung or bone marrow (data not shown). This contrasts with γδ thymocytes, all of which at least partially expressed CD1 (Fig. 6c, f), and CD4 and CD8β (Fig. 6i, l). Moreover, the majority of peripheral γδ T cells were found to be CD45RC+ (Fig. 6a, b, d, e) whereas a minor proportion of γδ thymocytes expressed CD45RC (Fig. 6c, f). The expression of CD45RC on peripheral γδ T lymphocytes was age-dependent in that the proportion of TCRγδ+ CD45RC+ cells significantly increased with age (Fig. 6, compare a with d and b with e).

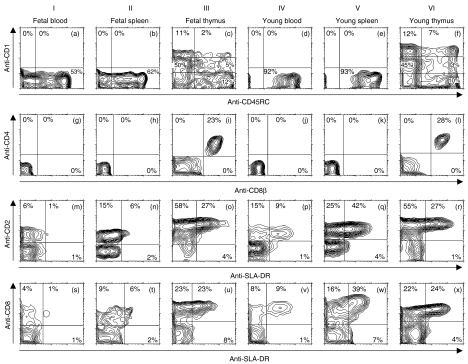

Figure 6.

Representative three-colour FCM analysis of CD1, CD2, CD4, pan-CD8, CD8β, CD45RC and MHC class II (SLA-DR) expression by TCRγδ+ lymphocytes isolated from blood (columns I and IV), spleen (columns II and V) and thymus (columns II and VI) of fetal (DG90, columns I–III) and young (8 days postnatally, columns IV–VI) piglets. Live (propidium iodide negative) TCRγδ+ thymocytes were gated and analysed for expression of following cell surface antigens: CD1/CD45RC (first row: a–f), CD4/CD8β (second row: g–l), CD2/SLA-DR (third row: m–r), and CD8/SLA-DR (fourth row: s–x). Indicated values in dot plots represent the percentages of TCRγδ+ thymocytes.

Differential MHC class II expression may indicate the origin of CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ T cells

When different organs at different age were analysed and compared for expression of MHC class II molecules (SLA-DR), the majority of peripheral γδ T cells in fetuses were MHC-II negative (Fig. 6m, n, s, t) whereas a substantial proportion of peripheral γδ T cells in young animals (Fig. 6p–q, v, w) and γδ thymocytes at any age (Fig. 6o, r, u, x, respectively) expressed MHC-II. A detailed analysis of MHC-II expression on TCRγδ+ cells showed that almost all MHC-II+ lymphocytes had a phenotype CD2+ CD8+ (Fig. 6m–x). These were composed of CD2+ CD4− CD8αα+ γδ T cells in the periphery and CD2+ CD4− CD8αα+ and CD2+ CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ T lymphocytes in the thymus (Figs 1b–d and 6g–x). For this reason, we analysed individual CD8+ γδ T cells with respect to their CD8αα, CD8αβ and MHC-II expression during ontogeny (Fig. 7). This analysis showed that the majority of MHC-II+ γδ thymocytes had the phenotype CD4+ CD8αβ+ while only few fetal γδ thymocytes were CD4− CD8αα+ MHC-II+ (Fig. 7, DG60–DG105). However, there was a substantial increase in the frequency of CD4− CD8αα+ MHC-II+ γδ thymocytes in older animals (Fig. 7; P < 0·0001 for 1-year-old pig in comparison with fetal piglets). A similar finding was seen for peripheral γδ T cells (Fig. 7, blood and spleen) in which the vast majority of CD4− CD8αα+ γδ T cells were MHC-II negative during gestation (P < 0·0001) while more then 50% were MHC-II positive after birth (P < 0·03). These observations correspond with earlier published data showing that expression of MHC-II on peripheral CD8αα+ γδ T cells may be an indicator of actual and/or previous activation14 and even that CD2+ CD8+ peripheral γδ T cells may serve as professional antigen-presenting cells.15

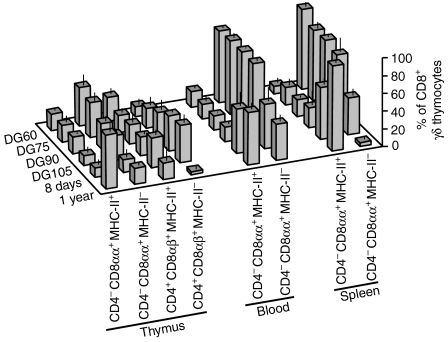

Figure 7.

Analysis of CD4− CD8αα+ and CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ lymphocyte subset frequency among CD8+ TCRγδ+ cells with respect to MHC class II expression. Lymphocytes isolated from thymus, blood and spleen (indicated on the x-axis) at different time points of prenatal and postnatal ontogeny were stained for CD4, pan-CD8, CD8β and MHC-II. Only live (propidium iodide negative) CD8+ TCRγδ+ lymphocytes were gated and analysed using FCM. The graph shows the proportion of CD4− CD8αα+ MHC-II+, CD4− CD8αα+ MHC-II−, CD4+ CD8αβ+ MHC-II+, and CD4+ CD8αβ+ MHC-II+ γδ T cells (phenotype indicated on the x-axis) inside CD8+ TCRγδ+ lymphocytes that represent 100% of cells. ‘DG’ stands for day of gestation and ‘days’ and ‘year’ refer to age of postnatal life (indicated on the z-axis). Individual bars represent average values and error bars represent the mean ± SEM obtained at least from four animals for each time point. The CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes have no counterpart in the periphery and therefore were omitted in graph.

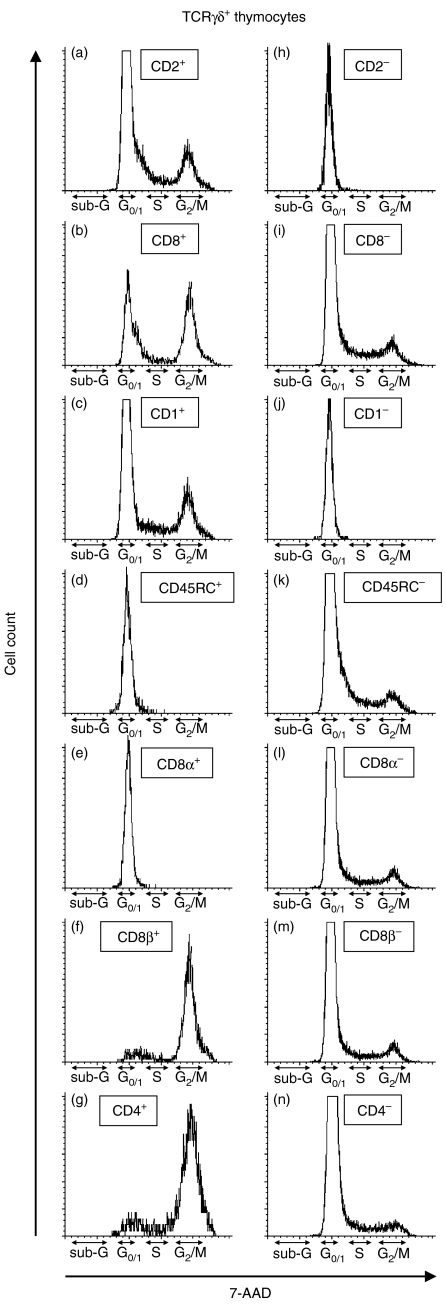

Cell cycle analysis revealed that CD1 and CD45RC are useful differentiation markers for γδ thymocyte lineages

Cell cycle analysis of γδ thymocyte subsets was based on simultaneous detection of surface phenotype and DNA staining using 7-AAD (Fig. 8). This analysis showed that only CD2+ γδ thymocytes had capacity to divide (Fig. 8a) while all CD2− γδ thymocytes were in G0/G1 phase (Fig. 8h). In this respect, both CD2+ CD8+ as well as CD2+ CD8− subsets may divide (Fig. 8b, i, respectively). Additional analysis showed that all cycling γδ thymocytes were large in size (data not shown) and expressed CD1 (either CD1lo or CD1hi, Fig. 8c) but did not express any CD45RC (Fig. 8k). Therefore, only γδ thymocytes with CD1+ CD45RC− phenotype could actively divide. Combining these findings with previous results on phenotyping of γδ thymocyte subsets, it appears that only four subsets of γδ thymocytes are candidates that can actively proliferate: subsets #1, #3, #7 and #10. Because CD8α+ γδ thymocytes did not divide (Fig. 8e), only the first three subsets were actually cycling. Interestingly, analysis of CD8β+ (Fig. 8f) and CD4+ (Fig. 8g) γδ thymocytes revealed that almost all were cycling. This indicates that subsets #1 and #3 have a very rapid turnover or are synchronized in the S/G2/M cell cycle phases.

Figure 8.

Representative FCM analysis of γδ thymocyte subpopulation in relationship to cell proliferation. Thymocytes isolated from 112-days-old fetuses were stained with anti-TCRγδ in combination with anti-CD2 (a, h), anti-CD8 (b, i), anti-CD1 (c, j), anti-CD45RC (d, k), anti-CD8 and anti-CD8β (e, l, f, m) or anti-CD4 (g, n). These were fixed in 70% ethanol and their DNA was visualized using 7-AAD. Only single γδ thymocytes inside both positive (left column) and negative (right column) cells for each depicted marker were gated and their DNA content was analysed by 7-AAD histograms. The similar results were obtained in all experiments independently of animal age and breed.

The fetal thymus is highly active as the generator of γδ T cells

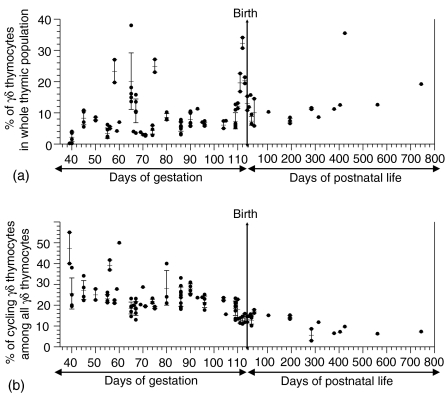

Analysis of cycling γδ thymocytes throughout gestation and in ageing postnatal animals (Fig. 9) showed that the proportion of dividing thymocytes decreased with age (CC < −0·59 at P < 2 × 10−5) and this decline was especially marked after birth (Fig. 9b). This decline was irrespective of the actual proportion of γδ thymocytes (Fig. 9a) as the frequency of all γδ thymocytes had tendency to increase (CC > +0·34 at P < 0·03). For example, up to 50% of all γδ thymocytes may be dividing during fetal life while less then 20% are dividing in young animals and less than 10% in animals older than 6 months.

Figure 9.

The proportion of all γδ thymocytes in whole thymic population (a) and the proportion of cycling γδ thymocytes among all γδ thymocytes (b). In both graphs, each data point represents analysis for one animal. When applicable, error bars represent the mean ± SEM with average value indicated by small horizontal lines inside each error bar. The time of birth is indicated by a vertical line across the graph.

We have shown in our previous study6 that the proportion of TCRγδ+ thymocytes increases between DG56 and DG74 reflecting colonization of the embryonic thymus by successive waves of progenitors from different haematopoietic centers.16 This increase was also observed in our current analysis of TCRγδ+ thymocytes (Fig. 9a; P < 0·04). We observed here that this is accompanied by a significant decrease (P < 0·005) in the frequency of cycling γδ thymocytes (corresponding dots on Fig. 9b). The similar increase in the proportion of all γδ thymocytes was observed around birth (Fig. 9a; P < 1 × 10−4).

Discussion

In this report, we describe 12 distinct subsets of γδ thymocytes based on their expression of CD1, CD2, CD4, the CD8 isoforms and CD45RC. We show that CD2/CD8-based phenotyping is unreliable for intrathymic differentiation for γδ T-cell lineage. Rather, the increased expression of CD45RC and loss of expression of CD1 is a better indicator of γδ thymocyte development. We suggest that γδ thymocytes develop sequentially from CD1+ CD45RC− to CD1− CD45RC− and then to CD1− CD45RC+ cells (Fig. 5). This scenario is based on the: (a) appearance of individual γδ thymocyte subsets during ontogeny (Figs 2 and 4); (b) finding that the level of surface CD1 expression increased while level of CD45RC expression decreased during ontogeny and thymocyte development (Figs 4 and 6); (c) capacity of individual γδ thymocyte subsets to divide (Fig. 8); and (d) absence of CD1+ while accumulation of CD45RC+ γδ T cells in the periphery (Fig. 6). Therefore, each of the three γδ thymocyte subsets defined by CD2 and CD8αα expression develops and matures in the thymus through separate differentiation pathways (Fig. 5).

CD1 expression on porcine γδ thymocytes is consistent with findings in humans in which only CD1+ γδ thymocytes express recombinase activation gene 1 (RAG-1), behave as functionally inert cells and differentiate into CD1− γδ thymocytes.17,18 Similarly, CD45RC in humans19 but not in the rat20 is selectively expressed on mature CD3εhi αβ and γδ thymocytes. Mutually exclusive expression of CD1 and CD45RC on porcine subsets defined by CD2/CD8αα expression is therefore a useful marker for further categorization of γδ thymocytes during development. Assuming that CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes represent an independent thymocyte lineage (see below), we show that among the γδ thymocyte subpopulations defined by CD2/CD8αα expression, only large CD2+ CD8− CD1+ CD45RC− γδ thymocytes (subset #7) were actively dividing (Fig. 8). This supports the notion that these cells are common precursors of all γδ T cells. We believe the cycling γδ thymocytes belonging to subset #7, represents the stage in γδ T-cell lineage development that immediately follows the rearrangement of the TCR genes. A similar phenomenon has been reported in mice where productive rearrangement and expression of both TCRγ and TCRδ genes is followed by proliferation.21 This proliferative developmental stage is followed by diversification into CD2+ CD8αα+, CD2+ CD8− and CD2− CD8− γδ thymocyte subsets (Fig. 5). The further maturation of these cells may be monitored by down-regulation of CD1 and up-regulation of CD45RC. In this respect, the absence of CD1+ γδ T cells in the periphery indicates that CD1+ γδ thymocytes are probably not exported from thymus. Although it is very probable that precursors within subset #7 are the direct progeny of a triple negative progenitor, we cannot yet determine the exact developmental period in which diversification to the γδ T-cell lineage occurs. This is due to the fact that it is impossible to distinguish between porcine pro-T, early pre-T and late pre-T cells, since porcine triple negative thymocytes cannot be divided on the base of CD25 expression.6 In any case, subset #7 represents the majority of all γδ thymocytes developing in fetal, neonatal and early postnatal thymus (Fig. 4c). The proportion of subset #7 also increases between DG55 and DG85 (Fig. 4c) which may reflect the time when colonization of the embryonic thymus by successive waves of progenitors from different haematopoietic centres occurs.6

Previous studies and those reported here suggest there may be two developmentally distinct subsets of CD2+ CD8αα+ peripheral γδ T cells. One develops in the thymus while the second acquires CD8αα in the periphery as a result of activation of CD8− thymus-dependent precursors. Should this be the case, it implies that all γδ T cells are originally derived from the thymus. This conclusion is in agreement with previously published results showing that all known chains of porcine TCRγδ are expressed within the thymus22 and is also supported by thymic export experiments showing that CD8αα+ γδ T cells constitute about 10% of recent thymic emigrants and are apparently naive T cells.23 It is also in agreement with the CD8αα expression profile of porcine peripheral lymphocytes. Among these cells CD4+ CD8− αβ T cells become CD4+ CD8αα+ αβ T cells24 and CD8αα− natural killer (NK) cells became CD8αα+ NK cells5 upon activation.

The origin of CD2+ CD8αα+ γδ T cells would also be monitored by MHC class II expression. Results presented here show that the majority of fetal thymic and peripheral CD8αα+ γδ lymphocytes were MHC-II− whereas the opposite is true postnatally (Fig. 7). This suggests that the coexpression of CD8αα and MHC-II in conventional animals is probably caused by activation by foreign antigens. Thus, peripheral CD2+ CD8αα+ MHC-II− γδ T cells appear to originate in the thymus, while CD2+ CD8αα+MHC-II+ γδ T cells arise in the periphery from their CD2+ CD8− MHC-II− or CD2+ CD8αα+ MHC-II− thymus-dependent precursors. We also showed in this study that the proportion of dividing thymocytes decreased with age, especially after birth (Fig. 9). The similar decrease was observed for the frequency of precursors in subset #7 (Fig. 4). This may indicate that the thymus is the most active site for generation of γδ T cells during the fetal period while the postnatal thymus might be repopulated by mature γδ T cells from the periphery. In support of this idea, there was remarkable accumulation of CD45RC+ γδ T cells in older thymi, the majority of which had the CD8αα+ MHC-II+ phenotype, suggesting they had originated in the periphery.

Within the thymus both CD4+ CD8αβ+ and CD4− CD8αα+ γδ subpopulations occur. While CD4− CD8αα+ γδ thymocytes fit the developmental pathway of the subsets defined by CD2/CD8αα expression (Fig. 5), the CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes (Figs 3 and 4, subsets 1–4) possess unusual features in comparison with all other γδ thymocytes. CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes: (1) bear exclusively CD8αβ (which is unique for any γδ T cells in any other organ); (2) are always CD1+ (indicating they do not mature at the terminal stage of T-cell development and are not exported from the thymus); (3) have no counterpart in the periphery (no CD4+ and/or CD8αβ+ and/or CD1+ γδ T cells were found in the periphery); (4) follow a different developmental pathway than other TCRγδ+ thymocytes (Fig. 5); (5) may coexpress CD45RC (which indicates some degree of maturation); and (6) are actively dividing (suggesting synchronization in particular developmental stage). These results suggest that CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes develop independently of other γδ thymocytes. Our most recent unpublished data indicate that CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes represent a transient and independent subpopulation resembling αβ T-lineage cells in their development. We believe that a substantial portion of CD4+ CD8αβ+ γδ thymocytes may re-enter the cell cycle and re-activate the TCRαβ gene rearrangement. It is noteworthy that CD4+ CD8+ γδ thymocytes also occur infrequently in humans18 and early and transiently during fetal development in mice.25,26 A very minor subpopulation has also been reported in chickens.27 CD4+ γδ T-cells can also be obtained in substantial numbers from human fetal liver after in vitro stimulation.28,29 Such cells are functionally inert in comparison with other γδ T cells as they do not produce interleukin-2 and are devoid of any cytolytic activity. Despite several reports, CD4+ γδ T cells remained obscure since their ontogeny, maturation state and place in the development of the γδ lineage is unclear. Perhaps CD4+ in many species can rapidly change their phenotype without defined intermediate stages.

In conclusion, we propose there are two major pathways of γδ thymocyte development (Fig. 5): (a) the CD2+ CD4− CD8− precursor pathway leading to the development of all TCRγδ+ subsets that bear the CD2/CD8αα phenotype and may be found in the periphery; and (b) the CD2+ CD4+ CD8αβ+ precursor pathway containing TCRγδ+ thymocytes that terminate their γδ development inside the thymus and are not exported into the periphery per se. We also propose that mature peripheral CD2+ CD8− γδ T cells may acquire CD8αα expression upon activation and this is accompanied by up-regulation of MHC-II expression. Studies on porcine CD4+ CD8αβ+ TCRγδ+ thymocytes may provide insight into the development of this subpopulation of thymocytes in many vertebrates.

Acknowledgments

We would like to gratefully acknowledge Lucie Poulová, Marta Stojková and Jakub Smola for excellent technical assistance and Professor John E. Butler from University of Iowa, Iowa, IA for critical reading of the manuscript. This work has been supported by a grant 524/04/0543 from the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic, a grant A5020303 from the Grant Agency of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, a DFG grant (HO 1521/3-2) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and a Institutional Research Concept no. AV0Z50200510.

Abbreviations

- CC

correlation coefficient

- FCM

flow cytometry

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- pAb

polyclonal antibody

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- DG

day of gestation

- SLA-DR

swine leucocyte antigen type DR (human MHC-II leucocyte antigen orthologue)

- DP

double positive

- 7-AAD

7-aminoactinomycin D

References

- 1.Kuhnlein P, Vicente A, Varas A, Hunig T, Zapata A. γ/δ T cells in fetal, neonatal, and adult rat lymphoid organs. Dev Immunol. 1995;4:181–8. doi: 10.1155/1995/73127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hein WR, Mackay CR. Prominence of γδ T cells in the ruminant immune system. Immunol Today. 1991;12:30–4. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90109-7. 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardoll DM, Fowlkes BJ, Bluestone JA, Kruisbeek A, Maloy WL, Coligan JE, Schwartz RH. Differential expression of two distinct T-cell receptors during thymocyte development. Nature. 1987;326:79–81. doi: 10.1038/326079a0. 10.1038/326079a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CL, Cihak J, Losch U, Cooper MD. Differential expression of two T cell receptors, TcR1 and TcR2, on chicken lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:539–43. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinkora M, Sinkora J, Rehakova Z, Splichal I, Yang H, Parkhouse RM, Trebichavsky I. Prenatal ontogeny of lymphocyte subpopulations in pigs. Immunology. 1988;95:595–603. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00641.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinkora M, Sinkora J, Rehakova Z, Butler JE. Early ontogeny of thymocytes in pigs: sequential colonization of the thymus by T cell progenitors. J Immunol. 2000;165:1832–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saalmuller A, Hirt W, Reddehase MJ. Porcine γ/δ T lymphocyte subsets differing in their propensity to home to lymphoid tissue. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2343–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang H, Parkhouse RM. Phenotypic classification of porcine lymphocyte subpopulations in blood and lymphoid tissues. Immunology. 1996;89:76–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-705.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-705.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddehase MJ, Saalmuller A, Hirt W. γ/δ T-lymphocyte subsets in swine. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1991;173:113–7. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76492-9_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H, Parkhouse RM. Differential expression of CD8 epitopes amongst porcine CD8-positive functional lymphocyte subsets. Immunology. 1997;92:45–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00308.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bruin MG, van Rooij EM, Voermans JJ, de Visser YE, Bianchi AT, Kimman TG. Establishment and characterization of porcine cytolytic cell lines and clones. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;59:337–47. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(97)00085-8. 10.1016/S0165-2427(97)00085-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinkora M, Sun J, Butler JE. Antibody repertoire development in fetal and neonatal piglets. V. VDJ gene chimeras resembling gene conversion products are generated at high frequency by PCR in vitro. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:1025–34. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(01)00022-0. 10.1016/S0161-5890(01)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinkora M, Sun J, Sinkorova J, Christenson RK, Ford SP, Butler JE. Antibody repertoire development in fetal and neonatal piglets. VI. B-cell lymphogenesis occurs at multiple sites with differences in the frequency of in-frame rearrangements. J Immunol. 2003;170:1781–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saalmuller A, Weiland F, Reddehase MJ. Resting porcine T lymphocytes expressing class II major histocompatibility antigen. Immunobiol. 1991;183:102–14. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takamatsu HH, Denyer MS, Wileman TE. A sub-population of circulating porcine γδ T cells can act as professional antigen presenting cells. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002;87:223–4. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(02)00083-1. 10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinkora M, Sinkorova J, Butler JE. B cell development and VDJ rearrangement in the fetal pig. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002;87:341–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(02)00062-4. 10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De la Hera A, Toribio ML, Martinez C. Delineation of human thymocytes with or without functional potential by CD1-specific antibodies. Int Immunol. 1989;1:496–502. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.5.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Offner F, Van Beneden K, Debacker V, Vanhecke D, Vandekerckhove B, Plum J, Leclercq G. Phenotypic and functional maturation of TCRγδ cells in the human thymus. J Immunol. 1997;158:4634–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zapata JM, Pulido R, Acevedo A, Sanchez-Madrid F, de Landazuri MO. Human CD45RC specificity: a novel marker for T cells at different maturation and activation stages. J Immunol. 1994;152:3852–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargreaves M, Bell EB. Identical expression of CD45R isoforms by CD45RC+‘revertant’ memory and CD45RC+ naive CD4 T cells. Immunology. 1997;91:323–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00267.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang J, Coles M, Cado D, Raulet DH. The developmental fate of T cells is critically influenced by TCRγδ expression. Immunity. 1998;8:427–38. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80548-8. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirt W, Saalmuller A, Reddehase MJ. Expression of γ/δ T cell receptors in porcine thymus. Immunobiol. 1993;188:70–81. doi: 10.1016/s0171-2985(11)80488-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Witherden DA, Kimpton WG, Abernethy NJ, Cahill RN. Changes in thymic export of γδ and αβ T cells during fetal and postnatal development. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2329–36. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zuckermann FA, Husmann RJ. Functional and phenotypic analysis of porcine peripheral blood CD4/CD8 double-positive T cells. Immunology. 1996;87:500–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itohara S, Nakanishi N, Kanagawa O, Kubo R, Tonegawa S. Monoclonal antibodies specific to native murine T-cell receptor γδ: analysis of γδ T cells during thymic ontogeny and in peripheral lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5094–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.13.5094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher AG, Ceredig R. γδ T cells expressing CD8 or CD4low appear early in murine foetal thymus development. Int Immunol. 1991;3:1323–8. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.12.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bucy RP, Chen CH, Cooper MD. Ontogeny of T cell receptors in the chicken thymus. J Immunol. 1990;144:1161–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aparicio P, Alonso JM, Toribio ML, Marcos MAR, Pezzi L, Martinez AC. Isolation and characterization of (γ,δ) CD4+ T cell clones derived from human fetal liver cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1009–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.1009. 10.1084/jem.170.3.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wucherpfennig KW, Liao YJ, Prendergast M, Prendergast J, Hafler DA, Strominger JL. Human fetal liver γ/δ T cells predominantly use unusual rearrangement of the T cell receptor δ and γ loci expressed on both CD4+ CD8− and CD4− CD8−γ/δ T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;177:425–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.425. 10.1084/jem.177.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]