Abstract

Immunostimulatory sequences (ISS) that contain CpG motifs have been demonstrated to exert antipathogen and antitumour immunity in animal models through several mechanisms, including the activation of natural killer (NK) cells to secrete interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and to exert lytic activity. Since NK cells lack the ISS receptor TLR9, the exact pathway by which NK cells are activated by ISS is unclear. We determined that ISS-induced IFN-γ from NK cells is primarily dependent upon IFN-α release from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs), which directly activates the NK cell. However, further analysis indicated that other PDC-released soluble factor(s) may contribute to IFN-γ induction. Indeed, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) was identified as a significant contributor to ISS-mediated activation of NK cells and was observed to act in an additive fashion with IFN-α in the induction of IFN-γ from NK cells and to up-regulate CD69 expression on NK cells. This activity of TNF-α, however, was dependent upon the presence of PDC-derived factors such as type I interferon. These results illustrate an important function for type I interferon in innate immunity, which is not only to activate effectors like NK cells directly, but also to prime them for enhanced activation by other factors such as TNF-α.

Keywords: CpG DNA, interferon-α, interferon-γ, natural killer cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells

Introduction

Therapies based on immunostimulatory sequences (ISS) have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of infection by a host of intracellular microbial pathogens, including bacteria, protozoans and viruses. ISS-based therapies have been used in animal models to directly treat/prevent infection by Leishmania major,1Listeria monocytogenes,2Plasmodium falciparum (malaria),3 and herpes simplex virus type 2.4 ISS has also been used as an adjuvant to boost vaccine immunogenicity in animals immunized with antigenic preparations derived from Mycobacterium tuberculosis,5Plasmodium falciparum,6Leishmania major,7 hepatitis B virus,8,9 hepatitis C virus,10 human papillomavirus,11 human immunodeficiency virus12 and influenza.13 Additionally, ISS has potent antitumour activity and has been observed to cause the regression and even eradication of several forms of cancer, including human and rodent models of cervical carcinoma,14,15 lymphoma,16 rhabdomyosarcoma,17 fibrosarcoma/thymoma18,19 and glioma.20

The mechanisms by which ISS mediates antipathogen or antitumour effects are varied and complex but can involve amplification of type I interferon, increasing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production and T helper type 1 (Th1) development, enhancing cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity, or augmenting natural killer (NK) cell activation and lytic ability. Most of the cell types that carry out ISS-directed immune responses (CD4 T cells, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, NK cells) are negative for expression of the ISS receptor, TLR9. Therefore, ISS-mediated signals must originate from other cells and be transmitted downstream to lymphocytes. The primary TLR9+ cells identified to date in human blood are B cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs). PDCs are thought to be primarily responsible for the initiation of ISS-augmented immunity, as their depletion is known to eliminate almost all the effects of ISS stimulation on human blood cells in vitro, except for particular B-cell effects.21–24

Human PDCs respond to ISS stimulation by increasing the expression of maturation markers such as CD80, CD86 and CD40, decreasing the rate of apoptosis, and initiating the release of cytokines, including tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-8. However, the most distinguishing effect of ISS on PDCs is the induction of high levels of IFN-α secretion, which is greatly amplified by the ‘C-class’ of ISS (CpG-C). Type I interferon has been often shown to be a potent driver of Th1 development and cell-mediated immunity, with particular implication in the activation of NK cells.25,26 Correspondingly, administration of ISS also results in NK-cell activation, and it is thought that IFN-α plays a major role in mediating the effects of ISS treatment. Indeed, ISS treatment loses efficacy in the induction of NK-mediated antitumour immunity in IFN-α receptor double-negative mice,19 thus suggesting a link between ISS-induced IFN-α and NK-cell activation.

NK cells have been observed to become activated in the presence of ISS-stimulated PDCs via a soluble PDC-derived factor that can be substituted with recombinant human (rh) IFN-α.27,28 Since bulk production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of ISS-stimulated IFN-γ is IFN-α-dependent,29 we investigated the link between ISS-induced IFN-α and NK-cell activity. We found that IFN-α is indeed the principal ISS-induced PDC-secreted factor responsible for promoting IFN-γ production by human NK cells. In addition, another ISS-induced PDC factor, TNF-α, participates in the induction of IFN-γ in an additive fashion, but this particular activity of TNF-α requires the presence of a cofactor such as IFN-α.

Materials and methods

Preparation of PBMCs, PDCs and NK cells

Peripheral blood was collected from healthy volunteers by venepuncture using heparinized syringes. PBMCs were isolated by centrifugation through a Ficoll (Pharmacia, Kirkland, Quebec, Canada) density gradient at 1500 g for 25 min. Enrichment of PDCs was performed using the Blood Dendritic Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, NK cells, T cells and monocytic cells were depleted from bulk PBMCs using a haptenated antibody cocktail of anti-CD3, anti-CD11b and anti-CD16, followed by magnetic labelling with anti-hapten microbeads and passage over an LD column with a MidiMACS or QuadroMACS magnet. Cells that did not bind to the column were then incubated with anti-BDCA-4 microbeads and then positively selected over two sequential LS or MS columns. Cell purity of > 95% was consistently obtained for the BDCA-2+ CDw123+ PDC phenotype. Isolation of human NK cells was performed by positive selection using CD56 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and passage over two sequential LS columns. NK-cell purity was consistently > 99% CD56+.

Cell culture

Following their isolation (day 0), the PDCs were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Bio-Whittaker, East Rutherford, NJ) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Gemini, Woodland, CA) plus 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 300 μg/ml l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Bio-Whittaker), and 1× non-essential amino acids (Bio-Whittaker). PDCs were cultured at 3 × 104−5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well round-bottomed plates with 5 μg/ml ISS for 20–24 hr, at which time PDC supernatants (SN) from multiple donors were harvested and pooled. Also on day 1, human NK cells were purified from fresh PBMCs. NK cells were plated in duplicate in 96-well round-bottomed plates at 3 × 105−4 × 105 cells/well in 100 μl of culture medium followed by the addition of 150 μl of fresh medium (containing either no addition, recombinant cytokines, or neutralizing antibodies) or 150 μl of PDC SN (containing either no addition, recombinant cytokines, or neutralizing antibodies). NK cells were incubated for 20–24 hr at 37°, then SNs were harvested and assayed for cytokine content using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Recombinant cytokines used in this study included: rhIFN-α and rhIFN-ω (PBL Biomedical Laboratories, Piscataway, NJ), rhIL-6, rhIL-8, rhIL-12, rhIL-15, rhIL-18 and rhTNF-α (all R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). All cytokines were used at 10 ng/ml except for rhIFN-α (2000 U/ml) and rhIFN-ω (2000 U/ml). For neutralization experiments, antibody cocktails were added that included both anti-cytokine and anti-receptor monoclonal antibodies. Neutralizing antibodies used in this study included: anti-hIFN-α, anti-hIFN-β, anti-hIFNα/β receptor (anti-hIFN-α/βR; PBL Biomedical Laboratories), anti-hTNF-α, anti-hTNF-αR, anti-hIL-6, anti-hIL-6R, anti-hIL-8, anti-hIL-8RA, anti-hIL-8RB, anti-hIL-18, anti-hIL-18R, anti-hIP-10 (all R & D Systems), anti-hIL-27 EBI3 (Odile Devergne, Paris University), and isotype controls (R & D Systems). All monoclonal antobodies were used at 5 μg/ml. Phosphorothioate oligodeoxynucleotides (PS ODNs) were synthesized as described previously.30 All ODNs were phosphorothioate and had < 5 endotoxin units/mg of ODN, determined by a Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker). Sequences: 1018 (CpG-B): 5′-TGACTGTGAACGTTCGAGATGA; C274 (CpG-C): 5′-TCGTCGAACGTTCGAGATGAT; negative control type-B: 5′-TGACTGTGAACCTTAGAGATGA.

ELISA

Human IFN-γ was assayed with CytoSet antibody pairs (BioSource, Camarillo, CA). Limits of maximal/minimal detection were 4000/2 pg/ml. Human IFN-α was assayed with an ELISA kit (PBL Biomedical Laboratories), and the limit of maximal/minimal detection was 13 160/16 pg/ml. Human TNF-α was assayed with an ELISA kit (Pharmingen), and the limit of maximal/minimal detection was 4000/2 pg/ml. Statistical significance was calculated using the paired t-test (graphpad instat) and the symbols representing significance are: ***P < 0·001; **P < 0·01; *P < 0·05.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Purified NK cells were cultured as described above with PDC-generated SNs for 20–24 hr. Cells were harvested and labelled with anti-CD69–fluoroisothiocyanate and anti-CD25–phycoerythrin (PharMingen). Acquisition and analysis were performed using a FACScaliber (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose).

Gene expression assay and analysis

Human purified PDCs were stimulated with 5 μg/ml ISS and cultured for 10 hr. Total RNA was extracted via the Qiagen RNeasy mini protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and was converted to cDNA using oligo-dT (Promega, Madison, WI), random hexamers (Promega), and SuperScript RT II (InVitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cDNA was diluted 1 : 3, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted using QuantiTect SYBR green PCR master mix (Qiagen) and naked primers (synthesized by Operon, Houtsville, AL), or QuantiTect probe PCR master mix (Qiagen) and PDAR (predeveloped TaqMan assay reagents) primers with labelled probe (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA). Reactions were conducted using the MyIQ Single Color reverse transcription (RT)-PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The sequences for primers synthesized for ubiquitin and IFN-α have been described previously.30 IL-6, IL-8, IL-12 p35, IL-12 p40, IL-18, interferon-inducible protein-10 (IP-10), and TNF-α were measured using PDARs supplied by Applied Biosystems. The sequences for primers for other genes were as follows (listed 5′ to 3′): IL-27 p28 (forward: GCGGAATCTCACCTGCCA, reverse: GGAAACATCAGGGAGCTGCTC); IL-27 EBI3 (forward: CCGAGCCAGGTACTACGTCC, reverse: CCAGTCACTCAGTTCCCCGT). Threshold cycle (CT) values for each gene were normalized to ubiquitin. The negative control for each experiment, stimulation with medium alone, was assigned a value of 1·0 and all data were expressed as fold induction over the negative control.

Results

IFN-α is required for ISS induction of IFN-γ from NK cells

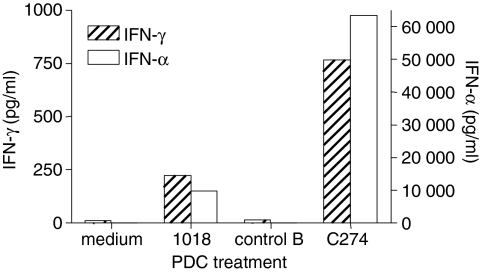

To determine whether ISS stimulates a soluble factor from PDCs that is responsible for the induction of IFN-γ by NK cells, we stimulated purified PDCs with the CpG-B 1018 or the CpG-C C274 for 24 hr, then removed cell-free SNs and used them to stimulate freshly purified NK cells. SNs from PDCs stimulated with 1018 and especially C274 resulted in significant levels of IFN-γ production by NK cells (Fig. 1). As expected, we also detected higher levels of IFN-α in the SNs from C274-stimulated PDCs, in accordance with the known potent IFN-α-inducing ability of CpG-C.21,30 Since CpG-C were optimal for induction of both IFN-α and IFN-γ, we utilized C274 for the remainder of this study. Preliminary examination of SNs derived from ISS-stimulated PDCs or ISS-stimulated NK cells had shown the complete absence of IFN-γ in the former and of IFN-α in the latter (data not shown), as expected. Furthermore, we have confirmed using RT-PCR assays the absence of IFN-α mRNA in ISS-stimulated NK cells and the absence of IFN-γ mRNA in ISS-stimulated PDCs (data not shown), which verified that in these cultures the IFN-α is PDC-derived and the IFN-γ is NK-cell-derived. These results confirm that cognate interaction between PDC and NK cells is not required, and that PDCs secrete a soluble factor that confers IFN-γ secretion activity on responding NK cells.

Figure 1.

A soluble factor produced by ISS-stimulated PDCs confers IFN-γ secretion to NK cells. Human PDCs were stimulated with CpG-B 1018, CpG-C C274, or a negative control ODN for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were collected and used to stimulate freshly purified NK cells for another 24 hr. These NK SNs were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ and IFN-α content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean of two donors, representative of two experiments.

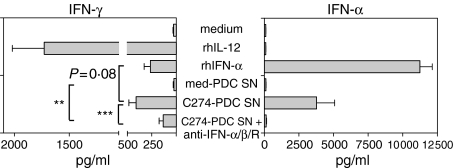

It has been shown that ISS-induced IFN-α from PDCs activates human NK cells to up-regulate CD69 expression27,28 and that blockade of type I interferon prevents ISS induction of IFN-γ in PBMCs.29 To confirm that IFN-α is also responsible for the induction of IFN-γ by purified NK cells, we stimulated NK cells with SNs from C274-stimulated PDC in the presence of an antibody cocktail neutralizing IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-α/βR. We found that IFN-γ induction was reduced on average by 67% (range 37–96%) by type I interferon blockade (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the reduction was only partial with most subjects, and the level of IFN-γ induced in the presence of anti-IFN-α/βR was still significantly higher than that induced by SNs from unstimulated PDCs. We verified that our antibody cocktail neutralized type I interferon by confirming that the IFN-γ-inducing effects of 2500 U/ml rhIFN-α on NK cells were completely blocked in the presence of anti-IFN-α/βR (data not shown). Moreover, rhIFN-α stimulation of NK cells resulted in 36% less IFN-γ production than C274-stimulated PDC SNs, despite the fact that three-fold more rhIFN-α was added than was naturally produced in the SNs.

Figure 2.

Blockade of type I interferon partially inhibits ISS-induced IFN-γ secretion. Human PDCs were stimulated with medium or CpG-C C274 for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were collected and used to stimulate freshly purified NK cells for another 24 hr in the presence of cytokines, neutralizing antibodies, or no stimulation. These NK SNs were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ and IFN-α content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM of 10 donors. **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Role of accessory factors in IFN-α-mediated induction of IFN-γ by NK cells

These data indicated that IFN-α may cooperate with an unidentified ISS-induced factor to induce higher levels of IFN-γ from NK cells than would be induced by IFN-α alone. This is borne out by the facts that: (1) type I interferon blockade (which we show to be effectively neutralizing of IFN-α) does not completely suppress ISS induction of IFN-γ; and (2) rhIFN-α is less effective than ISS-PDC SNs at IFN-γ induction, despite there being less IFN-α present in the SNs. Therefore, we set about to identify what other cytokine(s) might be participating in the ISS-mediated induction of IFN-γ from NK cells.

We stimulated purified PDCs with ISS and examined cytokine mRNA expression via RT-PCR (Table 1). RNA results indicated that, besides IFN-α, ISS-stimulated PDCs synthesize IL-6, IL-8, IL-27, IP-10 and TNF-α. Cytokines known for their ability to induce IFN-γ production from NK cells include IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-27 and IFN-ω.31–33 Although we observed little or no IL-12 or IL-18 expression either at the RNA level or the secreted protein level (data not shown), we included these two factors in our subsequent studies, because other reports have implicated them in the ISS-mediated cytokine response.34 To determine whether any of these cytokines might be contributing to ISS-induced IFN-γ induction, we stimulated NK cells with ISS-PDC SNs in the presence of recombinant cytokines and their respective neutralizing antibodies.

Table 1. Cytokine gene expression pattern of ISS-stimulated PDCs.

| C274 | Control C | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulus | Mean | SEM | Mean | SEM |

| IFN-α | 1991·0 | 1423·0 | 4·9 | 3·1 |

| TNF-α | 26·6 | 15·5 | 1·3 | 0·2 |

| IL-6 | 33·0 | 14·2 | 1·7 | 0·4 |

| IL-8 | 6·7 | 3·0 | 2·6 | 0·8 |

| IP-10 | 756·5 | 488·6 | 6·4 | 5·1 |

| IL-27 p28 | 66·4 | 37·3 | 4·4 | 3·1 |

| IL-27 EBI3 | 7·7 | 2·9 | 2·3 | 0·7 |

| IL-12 p40 | 0·9 | 0·2 | 1·9 | 0·3 |

| IL-12 p35 | 4·0 | 1·8 | 1·9 | 0·3 |

| IL-18 | 0·6 | 0·1 | 2·1 | 0·3 |

Human PDCs were stimulated with 5 μg/ml C274 or negative control CpG-C for 10 hr and then RNA was extracted and analysed via real-time PCR. The expression levels of 10 genes were normalized to ubiquitin expression. Data are presented as the mean of fold induction over medium control (given the value of 1·0) with SEM for four donors, and are representative of two experiments. Freshly isolated PDCs express mRNA for these genes at low levels similar to those from cells cultured for 10 hr in medium (used as the control).

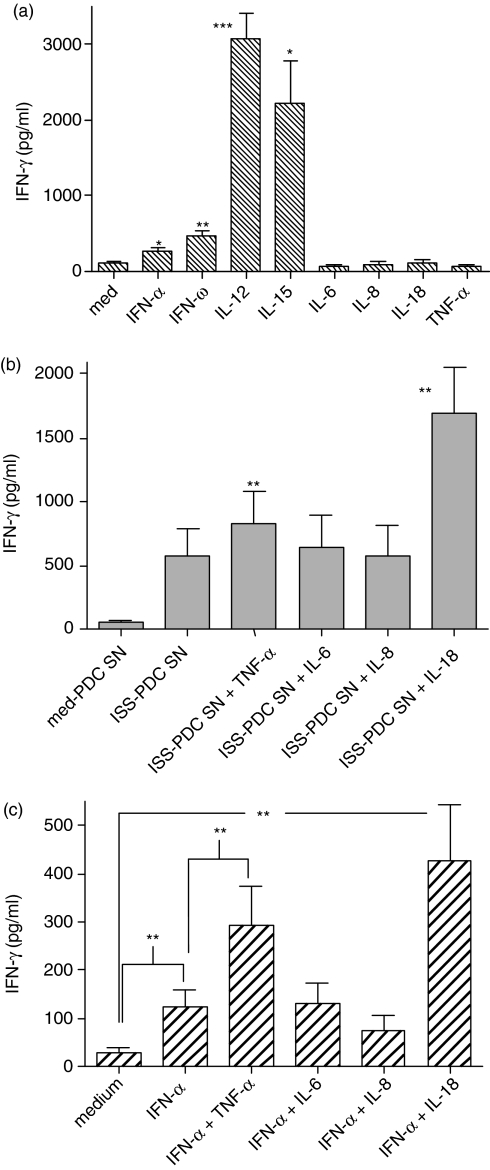

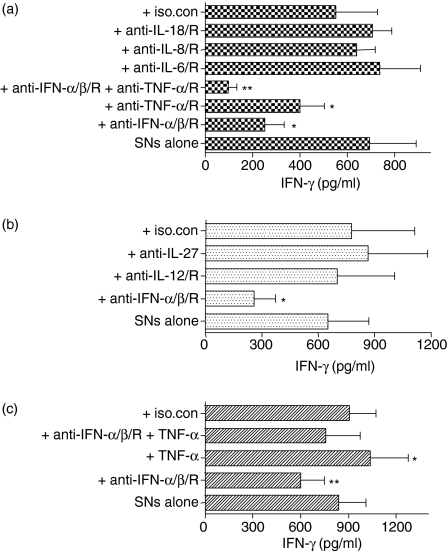

Purified NK cells did not respond with detectable IFN-γ to stimulation by IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, or TNF-α(Fig. 3a). Although IL-12 and IL-15 did induce IFN-γ production, they have not been shown to be secreted by ISS-stimulated PDCs (except IL-12 when CD40 ligand is also present in the stimulation35). When NK cells were stimulated with cytokines in the presence of ISS-PDC SNs, TNF-α was the only factor synthesized by ISS-stimulated PDCs that was found to have an additive effect on IFN-γ induction (Fig. 3b). IL-18 can also act synergistically with ISS-PDC SNs, although we found it was not synthesized by PDCs and thus could not be involved in the induction of NK-cell IFN-γ secretion by ISS-PDC SNs. This suggests that TNF-α requires the presence of another factor such as IFN-α to enhance IFN-γ induction, and indeed when rhIFN-α and rhTNF-α are combined, an additive effect on IFN-γ is observed (Fig. 3c), similar to the combination of ISS-PDC SNs + rhTNF-α. While neutralization of IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, IL-12, IL-27 (Fig. 4a,b) or IP-10 (data not shown) in C274-PDC SNs failed to affect the ability of the SN to elicit IFN-γ from NK cells, blockade of TNF-α partially reduced IFN-γ induction and blockade of both IFN-α and TNF-α resulted in an additive suppressive effect (Fig. 4a). Therefore, because either neutralization of the factor did not affect the IFN-γ-inducing activity of C274-PDC SN or the purified NK cells did not respond to the factor with IFN-γ production, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-27 and IP-10 were eliminated as participating factors with IFN-α in the induction of IFN-γ during ISS stimulation. Although IFN-ω is induced by ISS (J.D. Marshall and P. Yee, unpublished observations) and can exert IFN-γ-inducing activity (Fig. 3a), anti-IFN-αR neutralizes IFN-ω as well as IFN-α/β, because type I interferons ligate the same receptor (IFNAR). Therefore, IFN-ω is not responsible for the IFN-γ that remains induced by ISS-PDC SNs in the presence of anti-IFN-α/βR. TNF-α was the only factor examined that (1) is expressed by PDCs in response to ISS (Table 1 and Fig. 5); (2) had an additive enhancing effect with IFN-α on IFN-γ induction; and (3) the neutralization of which resulted in an additive effect on IFN-γ suppression with anti-type I interferon. Since we had observed that rhTNF-α only participated in NK-cell IFN-γ induction when administered in the presence of IFN-α/β (Fig. 3b,c), we determined whether rhTNF-α had any activity during type I interferon blockade of C274-PDC SNs (Fig. 4c). The addition of rhTNF-α modestly elevated NK-cell IFN-γ levels even during the neutralization of type I interferon, indicating that another unidentified factor(s) appears to be present in the C274-PDC SNs that enables TNF-α to contribute to IFN-γ induction. Thus, TNF-α has a contributory role in the ISS-mediated induction of IFN-γ by NK cells, but only if other factors such as IFN-α are present.

Figure 3.

NK-produced IFN-γ in response to cytokine stimulation. (a) Human NK cells were isolated and stimulated with cytokines for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were harvested and assayed for IFN-γ content via ELISA. Data are reported as the mean of six donors ±SEM. Statistical significance against medium stimulation was computed.(b) Human PDCs were stimulated with medium or CpG-C C274 for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were collected and used to stimulate freshly purified NK cells for another 24 hr in the presence of cytokines. These NK SNs were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM of five donors. Statistical significance against ISS-PDC SN was computed.(c) Human NK cells were isolated and stimulated with IFN-α+ cytokines for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were harvested and assayed for IFN-γ content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM of four to 10 donors. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Figure 4.

Effect of cytokine neutralization on ISS-induced IFN-γ secretion. Human PDCs were stimulated with medium or CpG-C C274 for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were collected and used to stimulate freshly purified NK cells for another 24 hr in the presence of neutralizing antibodies or cytokines. These NK-cell SNs were then harvested and assayed for IFN-γ content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM of five to seven donors. Statistical significance was computed against C274-PDC SNs alone. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01.

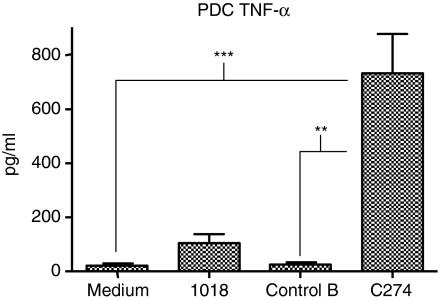

Figure 5.

Induction of TNF-α from PDCs by ISS. Human PDCs were stimulated with CpG-B 1018, CpG-C C274, or a negative control ODN for 24 hr. Cell-free SNs were collected and assayed for TNF-α content via ELISA. Results are reported as the mean ± SEM of 14 donors. **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

IFN-α and TNF-α combine for additive activation of NK cells

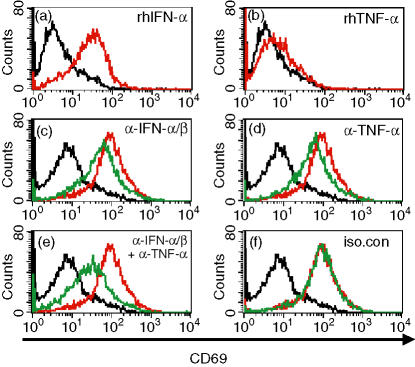

Upon stimulation, resting NK cells up-regulate the expression of the activation marker CD69. Although its function is unclear, the C-type lectin-like CD69 activates a number of signalling pathways, including Ca2+ influx36 and the activation of the tyrosine kinase Syk,37 and is useful as a marker for activated NK cells. We determined that stimulation of purified NK cells with rhIFN-α increased CD69 expression substantially but that stimulation with rhTNF-α did not (Fig. 6a,b), similar to the effects of IFN-α and TNF-α on IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 3a). In addition, treatment of NK cells with SNs from C274-stimulated PDCs also resulted in a substantial up-regulation of CD69 expression (Fig. 6c). In the presence of neutralizing antibodies to type I interferon or TNF-α, a partial inhibition of CD69 expression was observed (Fig. 6c,d), and blockade of both cytokines resulted in additive suppression (Fig. 6e). Blockade of IL-6 had no effect on PDC SN-stimulated CD69 expression (data not shown). Therefore, as with ISS-mediated induction of IFN-γ by NK cells, the ISS-mediated increase in CD69 expression on NK cells is also dependent on type I interferon and TNF-α produced by PDCs, but the efficacy of TNF-α is dependent on the presence of other soluble factors such as IFN-α.

Figure 6.

Dependency of ISS-mediated NK activation on IFN-α/TNF-α. (a,b) Human NK cells were isolated and stimulated with medium (black) or cytokines (red) for 24 hr. Cells were stained for CD69 expression and analysed by FACs. Data are from one representative donor of four. (c–f) Human PDCs were stimulated with CpG-C C274 for 24 hr, and cell-free SNs were collected. Freshly purified NK cells were stimulated with medium (black), C274-PDC SN (red), or C274-PDC SN + neutralizing antiboies (green) for another 24 hr. Cells were stained for CD69 expression and analysed by FACs. Data are from one representative donor of four.

Discussion

The activation of NK cells to secrete IFN-γ is central to the mediation of antiviral, antibacterial, and antitumour immunity by ISS (reviewed in ref. 38). Previous studies have implicated IFN-α as playing a major role in the activation of NK cells after ISS stimulation. ISS-stimulated PDCs have been shown to release a soluble factor that is responsible for the up-regulation of CD69 on NK cells, an activity mimicked by stimulation of NK cells with rhIFN-α.27,28 We determined that neutralization of type I interferon in SNs derived from ISS-stimulated PDCs did decrease subsequent IFN-γ production by purified NK cells (Fig. 2). These data are supported by the findings of others who observed that anti-IFN-α also inhibited ISS-stimulated IFN-γ in unseparated PBMCs.29 Furthermore, rhIFN-α also promotes NK activation to an extent similar to that observed with the ISS-PDC SNs (Fig. 2 and ref. 27). These data support the theory that IFN-α is the principal ISS-induced PDC-secreted factor responsible for promoting IFN-γ production by human NK cells.

However, our studies demonstrate that the mechanism by which ISS causes IFN-γ release by NK cells may be more complex than first assumed. Although required, IFN-α may not be the sole contributing factor to NK IFN-γ production, as supported by the following observations: (1) neutralization of IFN-α significantly reduces NK IFN-γ levels but only by approximately 67%; (2) addition of three-fold more IFN-α (in recombinant form) than is found contained within ISS-PDC SNs results in the induction of 36% less IFN-γ from NK cells; and (3) the CpG-C class of ISS induces IFN-α from human PBMCs with a bell-shaped dose–response curve but induces IFN-γ with a direct correlation, such that 2 μg/ml CpG-C induces optimally high IFN-α production with no detectable IFN-γ, while 20 μg/ml CpG-C induces optimally high IFN-γ production but much lower levels of IFN-α.30,39

To determine if another soluble factor cooperates with type I interferon (IFN-α/β/ω) in the induction of IFN-γ, we examined the sensitivity of NK-cell IFN-γ production to cytokine stimulation and neutralized several cytokines known to be present in ISS-stimulated PDC SNs or known to be inductive of IFN-γ from NK cells. Such studies eliminated a host of potential factors including IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-27 and IP-10 from playing a substantial role in this process, although not ruling out participation by a number of them simultaneously. It should be noted that once PDCs receive a signal through CD40 (from activated T cells in vivo or CD40 ligand in vitro), they also produce IL-12 in response to ISS stimulation.35 In such a case, PDC-produced IL-12 factors in the induction of NK-cell IFN-γ by ISS, but our studies are conducted in the absence of CD40 stimulation and therefore in the absence of IL-12, thus excluding it from consideration. Another APC-derived cytokine known to have IFN-γ-inducing activity on NK cells is IL-23 (reviewed in ref. 40). Since IL-23 shares recognition of the IL-12Rβ1 subunit with IL-12, administration of anti-IL-12Rβ1 should have neutralized IL-23 functionality as well as IL-12. In addition, we have examined ISS-stimulated PDCs for mRNA expression of the IL-23 subunits p19 and p40 and have found neither to be altered (data not shown), suggesting that ISS does not induce IL-23 secretion from PDCs.

Our studies did reveal a participating role for TNF-α. Interestingly, rhTNF-α on its own was unable to elicit IFN-γ production or CD69 expression by purified NK cells but could act in an additive fashion in the presence of rhIFN-α or type I interferon-containing ISS-PDC SNs. Accordingly, we also found that blockade of TNF-α signalling could partially but not completely inhibit ISS-mediated IFN-γ induction and CD69 up-regulation. Curiously, we found that neutralization of type I interferon only partially inhibited the effectiveness of ISS-PDC SNs to induce IFN-γ from NK cells and that neutralization of both IFN-α/β and TNF-α more completely inhibited IFN-γ induction. However, this suggests that the endogenously produced TNF-α in the SNs retained some measure of efficacy even when IFN-α/β had been neutralized. This would appear to contrast with our observation that rhTNF-α alone is ineffective at induction of NK-derived IFN-γ and relies on the presence of IFN-α to participate. The answer may be that another unidentified factor present in ISS-PDC SNs, besides type I interferon, allows NK cells to be responsive to TNF-α. Such a factor is not present when NK cells are stimulated only with rhTNF-α.

The mechanism by which TNF-α enhances the activity of type I interferon on NK cells is unclear. An examination of IFN-αR and TNF-αR expression on NK cells did not find any significant ability of IFN-α or TNF-α to up-regulate the receptor expression of the other (data not shown). Instead, TNF-α may act to increase the IFN-α-responsiveness of NK cells by up-regulating the expression of other genes in the type I interferon signalling pathway.

Similar findings have been reported by Hunter et al.41 who described the synergistic induction of IFN-γ from murine NK cells by IFN-α and TNF-α. Like our study, TNF-α was observed to be inactive unless in the presence of IFN-α. In addition, IFN-α and IL-6 induced from human PDCs by CD40 ligand stimulation were found to act in an additive fashion to induce B-cell differentiation and immunoglobulin secretion.22 Here again, a consistent requirement was observed for IFN-α to be present during IL-6 stimulation and that IL-6 stimulation alone was significantly less effective. Thus, an important emerging function of type I interferon from ISS-stimulated PDCs is to prime responder cells (NK cell, B cells) for simultaneous or subsequent stimulation with other PDC-derived factors, such as TNF-α and IL-6, which then amplify and complete the response.

A recent study has reported that resting human NK cells were unresponsive to CpG-A or CpG-B stimulation, but when stimulated in the presence of CpG plus suboptimal amounts of IL-12 or IL-8, NK cells expressed TLR9 mRNA and secreted IFN-γ.42 This runs counter to previous findings that showed human NK cells to express little or no TLR927,43 and to be unresponsive to CpG stimulation.27,29,44 Since NK cells have been shown to respond with IFN-γ production to other bacterial products recognized by TLRs, flagellin and outer membrane protein A,43 it is possible that NK cells can respond directly to ISS stimulation under some circumstances. However, the NK cells in question42 were not rigorously purified and thus may have contained contaminating PDCs that mediated the observed effect by ISS. Indeed, when we first purify NK cells by CD56 MACS microbead selection and then eliminate contaminating PDCs by BCDA-2 MACS microbead negative selection, the resulting NK population is completely unreactive to ISS stimulation (data not shown). Consequently, our studies show that an indirect mechanism mediated primarily by IFN-α is at least a major pathway of NK activation by ISS, if not the sole pathway.

Our findings concerning the roles of ISS-induced IFN-α and TNF-α in the activation of NK cells are supported by a recent report by Gerosa et al.45 which confirmed the additive effects of these cytokines in the enhancement of CD69 expression on human NK cells exposed to ISS-activated PDCs through a transwell membrane. However, these authors did not find that ISS induced IFN-γ from NK cells, even in the presence of PDCs. This may be because of the class of ISS used. While Gerosa et al. utilized examples of CpG-A and CpG-B, we used a CpG-C (C274) in our study, because we had previously found the C class to have the highest inductive capacity for IFN-γ induction in PBMCs or in the form of ISS-stimulated PDC SNs used to stimulate purified NK cells (data not shown).

In conclusion, our results support a model in which ISS is taken up by PDCs and signals for the synthesis and release of a number of cytokines including IFN-α and TNF-α. NK cells are activated by IFN-α to up-regulate CD69 and to produce IFN-γ. IFN-α and possibly another unidentified factor also activates NK responsiveness to TNF-α through an unknown mechanism, thus allowing enhancement of IFN-γ synthesis by TNF-α in an additive fashion. These results further underline the pivotal role played by type I interferon in mediating the effects of ISS in humans and suggest that ISS-formulated therapies to treat conditions susceptible to NK-mediated immunity, such as tumours, would be improved by the use of ISS engineered for optimal IFN-α induction (i.e. CpG-C).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to O. Devergne (Paris University, Paris) for the generous gift of anti-IL-27, to C. Fressola (Dynavax), L. Tracy and N. Lynn (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Alameda, CA) for phlebotomy services, and to N. Khounchanh (Dynavax) for technical support.

Abbreviations

- ISS

immunostimulatory sequences

- ISS-PDC SN

SN derived from ISS-stimulated PDCs

- PDC

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- SN

supernatant

References

- 1.Walker PS, Scharton-Kersten T, Krieg AM, Love-Homan L, Rowton ED, Udey MC, Vogel JC. Immunostimulatory oligodeoxynucleotides promote protective immunity and provide systemic therapy for leishmaniasis via IL-12- and IFN-gamma-dependent mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klinman DM, Conover J, Coban C. Repeated administration of synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides expressing CpG motifs provides long-term protection against bacterial infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5658–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5658-5663.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gramzinski RA, Doolan DL, Sedegah M, Davis HL, Krieg AM, Hoffman SL. Interleukin-12- and gamma interferon-dependent protection against malaria conferred by CpG oligodeoxynucleotide in mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1643–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1643-1649.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pyles RB, Higgins D, Chalk C, Zalar A, Eiden J, Brown C, Van Nest G, Stanberry LR. Use of immunostimulatory sequence-containing oligonucleotides as topical therapy for genital herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. J Virol. 2002;76:11387–96. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11387-11396.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freidag BL, Melton GB, Collins F, Klinman DM, Cheever A, Stobie L, Suen W, Seder RA. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and interleukin-12 improve the efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination in mice challenged with M. tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2948–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2948-2953.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones TR, Obaldia N, 3rd, Gramzinski RA, et al. Synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs enhance immunogenicity of a peptide malaria vaccine in Aotus monkeys. Vaccine. 1999;17:3065–71. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah JA, Darrah PA, Ambrozak DR, et al. Dendritic cells are responsible for the capacity of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides to act as an adjuvant for protective vaccine immunity against Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198:281–91. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halperin SA, Van Nest G, Smith B, Abtahi S, Whiley H, Eiden JJ. A phase I study of the safety and immunogenicity of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen co-administered with an immunostimulatory phosphorothioate oligonucleotide adjuvant. Vaccine. 2003;21:2461–7. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis HL, Suparto II, Weeratna RR, et al. CpG DNA overcomes hyporesponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine in orangutans. Vaccine. 2000;18:1920–4. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00443-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Encke J, zu Putlitz J, Stremmel W, Wands JR. CpG immuno-stimulatory motifs enhance humoral immune responses against hepatitis C virus core protein after DNA-based immunization. Arch Virol. 2003;148:435–48. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0935-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber S, Lane C, Brown DM, et al. Human papillomavirus virus-like particles are efficient oral immunogens when coadministered with Escherichia coli heat-labile enterotoxin mutant R192G or CpG DNA. J Virol. 2001;75:4752–60. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.10.4752-4760.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dumais N, Patrick A, Moss RB, Davis HL, Rosenthal KL. Mucosal immunization with inactivated human immunodeficiency virus plus CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induces genital immune responses and protection against intravaginal challenge. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:1098–105. doi: 10.1086/344232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph A, Louria-Hayon I, Plis-Finarov A, et al. Liposomal immunostimulatory DNA sequence (ISS-ODN): an efficient parenteral and mucosal adjuvant for influenza and hepatitis B vaccines. Vaccine. 2002;20:3342. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwaveling S, Ferreira Mota SC, Nouta J, Johnson M, Lipford GB, Offringa R, van der Burg SH, Melief CJ. Established human papillomavirus type 16-expressing tumors are effectively eradicated following vaccination with long peptides. J Immunol. 2002;169:350–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baines J, Celis E. Immune-mediated tumor regression induced by CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2693–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lonsdorf AS, Kuekrek H, Stern BV, Boehm BO, Lehmann PV, Tary-Lehmann M. Intratumor CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide injection induces protective antitumor T cell immunity. J Immunol. 2003;171:3941–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weigel BJ, Rodeberg DA, Krieg AM, Blazar BR. CpG oligodeoxynucleotides potentiate the antitumor effects of chemotherapy or tumor resection in an orthotopic murine model of rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawarada Y, Ganss R, Garbi N, Sacher T, Arnold B, Hammerling GJ. NK– and CD8(+) T cell-mediated eradication of established tumors by peritumoral injection of CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2001;167:5247–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hafner M, Zawatzky R, Hirtreiter C, Buurman WA, Echtenacher B, Hehlgans T, Mannel DN. Antimetastatic effect of CpG DNA mediated by type I IFN. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5523–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carpentier AF, Xie J, Mokhtari K, Delattre JY. Successful treatment of intracranial gliomas in rat by oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2469–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartmann G, Battiany J, Poeck H, Wagner M, Kerkmann M, Lubenow N, Rothenfusser S, Endres S. Rational design of new CpG oligonucleotides that combine B cell activation with high IFN-alpha induction in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1633–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jego G, Palucka AK, Blanck JP, Chalouni C, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 2003;19:225–34. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kemp TJ, Elzey BD, Griffith TS. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-derived IFN-alpha induces TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/Apo-2L-mediated antitumor activity by human monocytes following CpG oligodeoxynucleotide stimulation. J Immunol. 2003;171:212–18. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Ayyoub M, et al. CpG-A and CpG-B oligonucleotides differentially enhance human peptide-specific primary and memory CD8+ T-cell responses in vitro. Blood. 2004;103:2162–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito T, Amakawa R, Inaba M, Ikehara S, Inaba K, Fukuhara S. Differential regulation of human blood dendritic cell subsets by IFNs. J Immunol. 2001;166:2961–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagai T, Devergne O, Mueller TF, Perkins DL, van Seventer JM, van Seventer GA. Timing of IFN-beta exposure during human dendritic cell maturation and naive Th cell stimulation has contrasting effects on Th1 subset generation: a role for IFN-beta-mediated regulation of IL-12 family cytokines and IL-18 in naive Th cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2003;171:5233–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hornung V, Rothenfusser S, Britsch S, Krug A, Jahrsdorfer B, Giese T, Endres S, Hartmann G. Quantitative expression of toll-like receptor 1–10 mRNA in cellular subsets of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells and sensitivity to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. J Immunol. 2002;168:4531–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:709–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krug A, Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, et al. Identification of CpG oligonucleotide sequences with high induction of IFN-alpha/beta in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2154–63. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<2154::aid-immu2154>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marshall JD, Fearon K, Abbate C, Subramanian S, Yee P, Gregorio J, Coffman RL, Van Nest G. Identification of a novel CpG DNA class and motif that optimally stimulate B cell and plasmacytoid dendritic cell functions. J Leuko Biol. 2003;73:781–92. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strengell M, Matikainen S, Siren J, Lehtonen A, Foster D, Julkunen I, Sareneva T. IL-21 in synergy with IL-15 or IL-18 enhances IFN-gamma production in human NK and T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:5464–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pflanz S, Timans JC, Cheung J, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4 (+) T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adolf GR. Human interferon omega – a review. Mult Scler. 1995;1(Suppl. 1):S44–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohle B, Jahn-Schmid B, Maurer D, Kraft D, Ebner C. Oligodeoxynucleotides containing CpG motifs induce IL-12, IL-18 and IFN-gamma production in cells from allergic individuals and inhibit IgE synthesis in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:2344–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2344::AID-IMMU2344>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duramad O, Fearon KL, Chan JH, Kanzler H, Marshall JD, Coffman RL, Barrat FJ. IL-10 regulates plasmacytoid dendritic cell response to CpG containing immunostimulatory sequences. Blood. 2003;102:4487–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sancho D, Santis AG, Alonso-Lebrero JL, Viedma F, Tejedor R, Sanchez-Madrid F. Functional analysis of ligand-binding and signal transduction domains of CD69 and CD23 C-type lectin leukocyte receptors. J Immunol. 2000;165:3868–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pisegna S, Zingoni A, Pirozzi G, et al. Src-dependent Syk activation controls CD69-mediated signaling and function on human NK cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:68–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klinman DM. Immunotherapeutic uses of CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:249–59. doi: 10.1038/nri1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall JD, Fearon KL, Higgins D, et al. Superior activity of the type C class of ISS in vitro and in vivo across multiple species. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:63–72. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trinchieri G, Pflanz S, Kastelein RA. The IL-12 family of heterodimeric cytokines. new players in the regulation of T cell responses. Immunity. 2003;19:641–4. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunter CA, Gabriel KE, Radzanowski T, Neyer LE, Remington JS. Type I interferons enhance production of IFN-gamma by NK cells. Immunol Lett. 1997;59:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sivori S, Falco M, Della Chiesa M, Carlomagno S, Vitale M, Moretta L, Moretta A. CpG and double-stranded RNA trigger human NK cells by Toll-like receptors: induction of cytokine release and cytotoxicity against tumors and dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10116–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403744101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chalifour A, Jeannin P, Gauchat JF, Blaecke A, Malissard M, N'Guyen T, Thieblemont N, Delneste Y. Direct bacterial protein PAMP recognition by human NK cells involves TLRs and triggers alpha-defensin production. Blood. 2004;104:1778–83. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rothenfusser S, Hornung V, Krug A, Towarowski A, Krieg AM, Endres S, Hartmann G. Distinct CpG oligonucleotide sequences activate human gamma delta T cells via interferon-alpha/-beta. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3525–34. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3525::aid-immu3525>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerosa F, Gobbi A, Zorzi P, Burg S, Briere F, Carra G, Trinchieri G. The reciprocal interaction of NK cells with plasmacytoid or myeloid dendritic cells profoundly affects innate resistance functions. J Immunol. 2005;174:727–34. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]