Abstract

A number of signaling proteins have been demonstrated to interact with follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor (FSHR), including APPL1, 14-3-3τ and Akt2. To further define the repertoire of proteins involved in FSH-induced signal transduction, several signaling and adapter proteins were examined for the ability to associate with FSHR. This report shows that, in addition to APPL1, FSHR interacts with FOXO1a and APPL2. Moreover, APPL1 and APPL2 associate with one another via the N-terminus of APPL1, presumably via the BAR domain. The interactions between FSHR and APPL2 and between FSHR and FOXO1a evidently are distinct since FOXO1a does not associate with either APPL1 or with APPL2. Though APPL1 and APPL2 show some similarity in primary sequence, APPL1 associates with Akt2, whereas APPL2 does not. This is the first documented difference in function between APPL1 and APPL2. These results suggest that FSHR, APPL1, APPL2, Akt2 and FOXO1a are organized into distinct scaffolding networks in the cell. Accordingly, the spatial organization of signaling and adapter proteins with FSHR likely facilitates and finely regulates the signal transduction induced by FSH.

Keywords: follicle stimulating hormone receptor (human), Signal transduction, APPL1, APPL2

Introduction

FSH is required for fertility in females, where it binds to FSHR on granulosa cells in the ovary. In males, FSHR is present on Sertoli cells in the testes. FSH is necessary for high quality sperm production and normal testicular volume.

The induction of cAMP with subsequent activation of protein kinase A (PKA) is a well-documented mode of signaling upon the binding of FSH to FSHR (Dias et al., 2002). A number of studies have also underlined the importance of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway in FSH signaling. FSH stimulates the PI3K/Akt pathway by both PKA-dependent and -independent means (Gonzalez-Robayna et al., 2000). Furthermore, Akt2 co-immunoprecipitates with FSHR (Nechamen et al., 2004), and FOXO1a, the downstream target of Akt, is excluded from the nucleus after FSH treatment (Cunningham et al., 2003). An investigation of downstream targets reveals that hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) activity is stimulated by FSH through a mechanism involving PI3K, Akt, Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) (Alam et al., 2004).

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway also comes into play in FSH signaling. FSH appears to activate p38 MAPK (Maizels et al., 1998) and to regulate DNA synthesis in granulosa cells via the MAPK pathway (Yang and Roy, 2004). In addition, PKA indirectly increases extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling by turning off an inhibitory ERK phosphatase after FSH stimulation (Cottom et al., 2003).

Adapter and scaffolding proteins, including A kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs), β-arrestin 1 and receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs), play critical roles in signaling by bringing interacting proteins into proximity with one another and by organizing signaling networks in subcellular domains (Vondriska et al., 2004). AKAPs target PKA and specific binding partners to subcellular locations (Wong and Scott, 2004). Interestingly, FSH induces the expression of an AKAP, namely, MAP2D (Salvador et al., 2004).

Originally, β-arrestin 1 was thought to function in the desensitization of GPCRs after ligand binding (Lefkowitz, 1998), but its function has since been broadened to include the internalization of GPCRs through binding to clathrin in clathrin-coated pits (Gagnon et al., 1998) and acting as a scaffold for the assembly of ERK signaling complexes (Luttrell et al., 2001). Moreover, RAMPs have been implicated in post-endocytic sorting of a GPCR (Bomberger et al., 2005).

Recent results from this laboratory have identified an association of APPL1 with FSHR (Nechamen et al., 2004). APPL1 (Adapter protein with PH domain, PTB domain and Leucine zipper) has been shown to interact with a number of signaling proteins and receptors. Also referred to as APPL or DIP13α, APPL1 interacts with the p110α catalytic subunit of PI3K and inactive Akt (Mitsuuchi et al., 1999), androgen receptor and the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K (Yang et al., 2003) and DCC (Deleted in Colorectal Cancer) (Liu et al., 2002). In addition, APPL1 and APPL2 interact with Rab5, an important regulator of endocytosis.

The possibility that APPL1 and APPL2 recruit the PI3K signaling molecules Akt2 and FOXO1a into a complex with FSHR was investigated in this report. The finding that certain signaling proteins interact with FSHR but not with one another, suggests that these interactions are occurring in subcellular compartments and that the spatial organization of these proteins is an integral element in signal transduction.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

In order to add a C-terminal myc epitope to APPL1 and APPL2, PCR was performed on a plasmid containing the APPL2 cDNA (pDONR201/DIP13β) or on a plasmid containing the APPL1 cDNA. The PCR product was inserted into pcDNA3.1/myc-His (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to generate myc and His-tagged APPL1 or APPL2. The APPL1 plasmids which contain an N-terminal FLAG epitope, have been described (Nechamen et al., 2004). The HA-tagged Akt2 plasmid construction has been described (Mitsuuchi et al., 1998). FLAG-tagged FOXO1a plasmids, both wt and the AAA phosphorylation-defective mutant (Tang et al., 1999), were generously provided by Frederic Barr (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA). An SGK cDNA clone (NM_005627) was obtained from Origene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD) and was inserted into pcDNA3.1/myc-His to generate myc-tagged SGK.

Cell culture and transfections

HEK 293 cells stably expressing human FSHR (293/FSHR cells) (Nechamen and Dias, 2003) were maintained in Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. Subconfluent cells in 60 mm dishes were transfected (Lipofectamine Plus, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with plasmids (1 μg/dish) and incubated for an additional 24 hours. Cells were treated with 1.1 nM human pituitary FSH in serum-free Eagle's medium for the indicated times. Where indicated, cells were treated with 6.6 nM IGF-1 (National Hormone & Peptide Program, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA) for 30 minutes in serum-free Eagle's medium.

Immunoprecipitation

A 60 mm dish of cells was harvested in 1.0 ml of Igepal-DOC lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% Igepal, 0.4% deoxycholate, 140 mM NaCl, 6.6 mM EDTA) with protease inhibitors (10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 16 μg/ml benzamide, 10 μg/ml 1,10 phenanthroline, 1 mM PMSF) and immunoprecipitated as described in (Nechamen and Dias, 2003). Sodium orthovanadate (1mM) was included in experiments examining phosphorylated proteins. Protein concentrations were determined in a BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

The following antibodies were used in this study: mAb106.105 (specific for FSHR (Lindau-Shepard et al., 2001)), FLAG M2 mAb (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), myc mAb clone 9E10 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), an IgG2b mAb used as an isotype control (kindly provided by Dr. Gary Winslow, Wadsworth Center, Albany, NY), mouse IgG1 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), rabbit phosphoserine Ab (Zymed, S. San Francisco, CA), rabbit HA tag Ab and SGK Ab (Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions, Charlottesville, VA).

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Immunoblotting

An aliquot of 60 μl of 2X Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) was added to immunoprecipitates, samples were heated at 60° C for 5 min and 15 μl (1/4 of immunoprecipitate) were loaded per lane on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. After separation, the proteins were transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. Membranes were blocked in TBST [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20] (Bjerrum and Schafer-Nielsen, 1986) with 5% non-fat dry milk overnight at 4°C. Blots were washed briefly in TBST and probed with mAb 106.105 (5 μg) for 1 h at room temperature. Blots were washed and incubated with goat anti-mouse Ab (1:10,000) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Biosource, Camarillo, CA) for 1 h at room temperature. In the case of HA tag Ab, blots were blocked for 1 h at room temperature and probed (10 μg) overnight at 4° C. The secondary Ab was HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000) (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). Alternatively, blots were probed with HRP-conjugated FLAG M2 mAb (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) (1:5000) for 1 h at room temperature.

In the case of myc mAb and phosphoserine Ab, blots were blocked and probed in TBST with 3% BSA. Blots were probed with 10 μg of biotinylated myc mAb, prepared according to manufacturer's instructions for EZ Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Blots were then washed and incubated with 10 μg of HRP-streptavidin (Pierce, Rockford, IL). In the case of phosphoserine Ab, blots were blocked for 1 h at room temperature, probed (1:1000) overnight at 4° C and incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ab (1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Signal was developed using enhanced chemiluminescence western blot detection reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Results

APPL2 associates with FSHR

Previous results, using a yeast two hybrid screen, identified APPL1 as an interacting protein with FSHR (Nechamen et al., 2004). A related protein, APPL2, shares 54% identity with APPL1 and has a similar domain organization (Miaczynska et al., 2004). To determine whether FSHR also interacts with APPL2, a stable cell line of HEK 293 cells expressing FSHR (293/FSHR) was transfected with myc-tagged APPL2. FSHR was immunoprecipitated with the FSHR-specific mAb 106.105 (Lindau-Shepard et al., 2001) and the presence of APPL2 in immunoprecipitates was detected by probing immunoblots with myc mAb (Fig. 1). The presence of FSHR in immunoprecipitates was confirmed by probing immunoblots with mAb 106.105. APPL2 is detected in immune complexes with FSHR and treatment with FSH has no effect on the association of APPL2 with FSHR, demonstrating that APPL2 is constitutively associated with FSHR. The specificity of the interaction between FSHR and APPL2 was demonstrated by immunoprecipitating extracts with the isotype control IgG2b and probing immunoblots with myc mAb and 106.105 mAb (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

APPL2 co-immunoprecipitates with FSHR. HEK 293/FSHR cells were transfected with myc-tagged APPL2 or mock transfected, serum-starved for 2 h and treated with FSH for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with FSHR-specific mAb 106.105 or with the isotype control IgG2b. Samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes. Blots were probed with myc mAb to detect myc-tagged APPL2 or with mAb 106.105 to detect FSHR. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

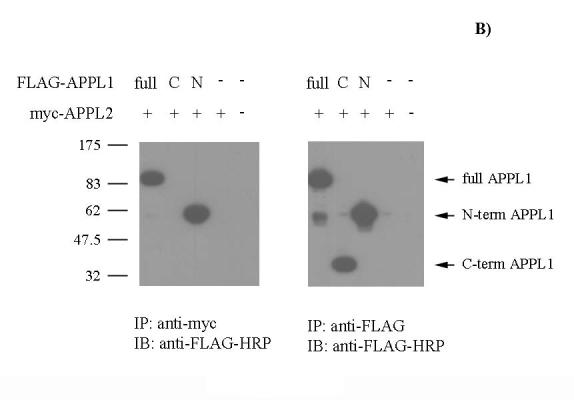

APPL1 and APPL2 interact with one another

The sequence homology and the BAR domain (Habermann, 2004) shared by APPL1 and APPL2, suggested that the two proteins could dimerize. To investigate this possibility, FLAG-tagged APPL1 and myc-tagged APPL2 were co-expressed in 293/FSHR cells. As shown in Figure 2A, APPL1 associates with APPL2 and treatment with FSH has little effect on the interaction.

Figure 2.

APPL1 and 2 interact with one another via the N-terminus of APPL1. A) HEK 293/FSHR cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged APPL1 and myc-tagged APPL2 or were mock transfected. Cells were treated with FSH for the indicated times. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with myc or FLAG mAb and immunoblots were probed with HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb or with myc mAb. B) HEK 293/FSHR cells were transfected with myc-tagged APPL2 and with full length (a.a. 1-709), C-terminal (C) (a.a. 461-709) or N-terminal (N) (a.a. 1-460) fragments of FLAG-tagged APPL1 or were mock transfected. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with myc or FLAG mAb and immunoblots were probed with HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

To further define the site of interaction between APPL1 and APPL2, 293/FSHR cells were co-transfected with full-length myc-tagged APPL2 and three different constructs of FLAG-tagged APPL1: full-length, a C-terminal fragment and an N-terminal fragment (Fig. 2B). Only the full-length and the N-terminal fragment (amino acids 1-460) of APPL1 co-immunoprecipitate with APPL2 indicating that APPL1 and APPL2 interact via the N-terminus of APPL1.

FOXO1a associates with FSHR

Previous results demonstrated an interaction between FSHR and Akt2 (Nechamen et al., 2004). In addition, FSH stimulation induces a rapid phosphorylation of FOXO1a, the downstream target of Akt, but a delayed phosphorylation of Akt2 in 293/FSHR cells. Consequently, it was of interest to determine whether FOXO1a interacts with FSHR. Figure 3 demonstrates that FLAG-tagged FOXO1a, when transfected into 293/FSHR cells, co-immunoprecipitates with FSHR, although FSH appears to have little effect on the association of FOXO1a with FSHR.

Figure 3.

FOXO1a interacts with FSHR. HEK 293/FSHR cells, transfected with FLAG-tagged FOXO1a or mock transfected, were treated with FSH for the indicated times. FSHR was immunoprecipitated with mAb106.105 and immunoblots were probed with HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb to detect FLAG-FOXO1a. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

FOXO1a does not co-immunoprecipitate with APPL2

Although APPL2 and FOXO1a associate with FSHR (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3, respectively), FOXO1a does not appear to interact with APPL2 (Fig. 4). FLAG-tagged FOXO1a is expressed when it is co-transfected into 293/FSHR cells with myc-tagged APPL2 but it is not found in immune complexes with APPL2 (Fig. 4). Likewise, a constitutively active mutant of FOXO1a, AAA-FOXO1a, in which the three phosphorylation sites of FOXO1a have been mutated to alanine, does not interact with APPL2 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

APPL2 does not co-immunoprecipitate with wt or mutant FOXO1a. Myc-tagged APPL2 and either FLAG-tagged wt FOXO1a or FLAG-tagged AAA-FOXO1a were co-transfected into HEK 293/FSHR cells and treated with FSH or IGF-1 for 30 minutes. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with myc mAb, FLAG mAb or the isotype control IgG1. Immunoblots were probed with HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb to detect FLAG-tagged FOXO1a or with myc mAb to detect myc-tagged APPL2. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

APPL1 does not interact with FOXO1a

Previous results had indicated that APPL1 interacts with FSHR ((Nechamen et al., 2004) and this report shows that FOXO1a associates with FSHR (Fig. 3). However, APPL1 does not appear to interact with FOXO1a (Fig. 5). Myc-tagged APPL1 (Fig. 5C) and FLAG-tagged wt or AAA-FOXO1a are expressed at high levels when co-transfected into 293/FSHR cells, but APPL1 and FOXO1a are not detected together in immune complexes (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

APPL1 does not associate with wt or mutant FOXO1a. Myc-tagged APPL1 and either FLAG-tagged wt FOXO1a or FLAG-tagged AAA-FOXO1a were cotransfected into HEK 293/FSHR cells. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with FLAG mAb and immunoblots were probed with either myc mAb to detect coimmunoprecipitated myc-tagged APPL1 (A) or with FLAG mAb to detect FLAG-tagged FOXO1a (B). Cell extracts were also immunoprecipitated with myc mAb and the immunoblot was probed with myc mAb to detect myc-tagged APPL1 (C). The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

FSH stimulation does not induce phosphorylation of SGK

An alternative kinase in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway for phosphorylating FOXO1a is serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK). We reasoned that FSH could activate SGK, which in turn would phosphorylate FOXO1a in 293/FSHR cells. Although SGK is phosphorylated on serine in response to IGF-1 treatment, phosphorylated SGK was not detected after FSH stimulation (Fig. 6), suggesting that SGK is not a key player in FSH-mediated signaling in 293/FSHR cells.

Figure 6.

SGK is not phosphorylated in response to FSH. HEK 293/FSHR cells were transfected with myc-tagged SGK and treated with either FSH or IGF-1 for the indicated times. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with myc mAb and immunoblots were probed with anti-phosphoserine Ab to detect SGK phosphorylated on serine. The experiment was performed twice; the better blot is shown.

SGK is not associated with FSHR

Basal levels of phosphorylated SGK may phosphorylate FOXO1a if brought into close contact with FOXO1a. However, SGK does not co-immunoprecipitate with FSHR from 293/FSHR cells transfected with myc-tagged SGK (Fig. 7). Thus, in contrast to Akt2 and FOXO1a, SGK does not appear to interact with FSHR and it is therefore unlikely that SGK phosphorylates FOXO1a in an FSHR signaling complex.

Figure 7.

SGK is not associated with FSHR. HEK 293/FSHR cells were transfected with myc-tagged SGK and treated with FSH as indicated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mAb 106.105 or with myc mAb. Immunoblots were probed with anti-SGK Ab to detect myc-tagged SGK or probed with mAb 106.105 to detect FSHR. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

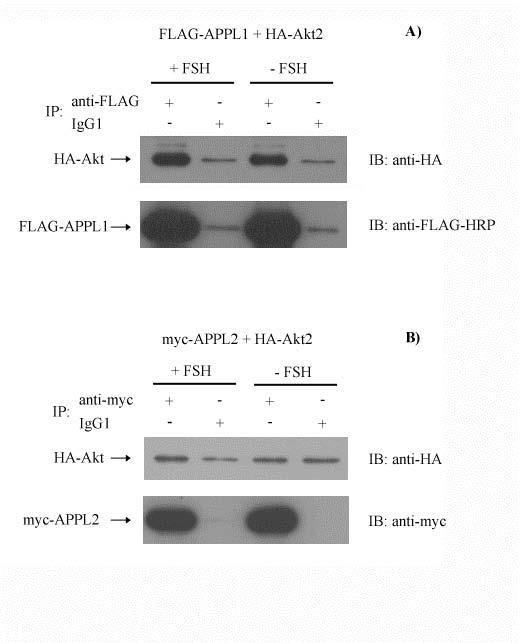

APPL1, but not APPL2, interacts with Akt2

Since previous results had demonstrated an association between Akt2 and APPL1 (Mitsuuchi et al., 1999),(Nechamen et al., 2004), it was of interest to test for a similar interaction between Akt2 and APPL2. Akt2 appears to interact with APPL1 but does not specifically interact with APPL2 (Fig. 8), the first documented difference in function between APPL1 and APPL2.

Figure 8.

Akt2 associates with APPL1, but not APPL2. HEK 293/FSHR cells were cotransfected with FLAG-tagged APPL1 and HA-tagged Akt2 (panel A) or with myc-tagged APPL2 and HA-tagged Akt2 (panel B). Cells were treated with or without FSH for 30 minutes and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with FLAG mAb, myc mAb or IgG1 Ab. Immunoblots were probed with anti-HA Ab to detect HA-tagged Akt2, with HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb to detect FLAG-tagged APPL1 or with myc mAb to detect myc-tagged APPL2. The experiment was performed twice; a representative blot is shown.

Discussion

A number of signaling proteins have been demonstrated to interact with FSHR, including APPL1 and Akt2 (Nechamen et al., 2004), 14-3-3τ (Cohen et al., 2004) and, in this report, APPL2 and FOXO1a. These interactions are often presumed to occur at the cell membrane, but, in fact, they could occur in a number of other cellular compartments, including endosomes, Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

Some of the signaling proteins shown to associate with FSHR do not appear to directly interact with one another. For instance, although FSHR co-immunoprecipitates with APPL1, APPL2, Akt2 and FOXO1a, there is no detectable interaction between FOXO1a and APPL1 or between FOXO1a and APPL2. In addition, no interaction could be detected between Akt2 and APPL2. This suggests that FSHR associates with these proteins in distinct subcellular domains. Alternatively, association of a protein with FSHR may preclude association with other adapters or two proteins may bind to the same domain of FSHR. The spatial organization of signaling proteins and adapters with FSHR is likely to be a key component in regulating signal transduction.

The finding that APPL1 and APPL2 associate with each other via the N-terminus of APPL1 is significant because the N-terminus contains the BAR (Bin-Amphiphysin-Rvs) domain (Habermann, 2004). The BAR domain appears to promote dimerization (Peter et al., 2004), (Ringstad et al., 2001), in addition to being implicated in a number of activities that are potentially important in signaling. Among these activities are sensing or inducing membrane curvature (Peter et al., 2004), (Farsad et al., 2001) and interaction with small GTPases (Miaczynska et al., 2004), (Tarricone et al., 2001).

Previous results (Nechamen et al., 2004) indicated that FOXO1a is rapidly phosphorylated after FSH treatment of 293/FSHR cells without a corresponding rapid phosphorylation of Akt2. One possibility for the FSH-induced phosphorylation of FOXO1a is SGK, another upstream kinase for FOXO1a. However, this does not appear likely, since SGK is not appreciably phosphorylated after FSH treatment; moreover basal phophorylated SGK is unlikely to play a role since SGK does not co-immunoprecipitate with FSHR in 293/FSHR cells.

The association of APPL1 with Akt2 (Nechamen et al., 2004), however, suggests a role for APPL1 in regulating the phosphorylation of FOXO1a by Akt2. The fact that APPL2 does not interact with Akt2 or with FOXO1a implies a divergence in function between APPL1 and APPL2. The balance between APPL1 binding to Akt2 and its binding to APPL2 may further modulate signaling.

In summary, these data suggest that the concept that FSHR is a homogeneous population with every receptor bound to a G protein which in turn activates the cAMP pathway is probably outdated. Current evidence suggests a model in which FSHR is a heterogeneous population of receptors bound to a variety of signaling molecules linked to the cAMP, PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. These signaling complexes are likely organized in spatially distinct compartments or subcellular domains. Certain proteins may exist in a pre-assembled scaffold with additional proteins being recruited to the complex or becoming phosphorylated in response to hormone binding. This study suggests that APPL1 and APPL2 play key roles in regulating these signaling networks.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Kate Farley in this work. George Bousfield (Wichita State University, Wichita, KS) provided a human pituitary crude extract (GTN fraction) from which FSH was purified in our laboratory. Linda O'Keefe, Hiroko Yoshinari and Gerald Kornatowski in the Tissue Culture Facility, Wadsworth Center, supplied the HEK 293/FSHR cells. DNA sequencing was performed by the Wadsworth Center Molecular Genetics Core Facility. Heidi Chial and Yong Q. Chen generously provided the APPL2 (DIP13β) cDNA. This research was supported by grant NIH-HD18407.

References

- Alam H, Maizels ET, Park Y, Ghaey S, Feiger ZJ, Chandel NS, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Follicle-stimulating hormone activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT/Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway is necessary for induction of select protein markers of follicular differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:19431–19440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401235200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerrum OJ, Schafer-Nielsen C. In: Analytical Electrophoresis. Dunn MJ, editor. Verlag Chemie; Weinheim: 1986. p. 315. [Google Scholar]

- Bomberger JM, Parameswaran N, Hall CS, Aiyar N, Spielman WS. Novel function for receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs) in post-endocytic receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9297–9307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413786200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen BD, Nechamen CA, Dias JA. Human follitropin receptor (FSHR) interacts with the adapter protein 14-3-3 tau. Molec Cell Endocrinol. 2004;220:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottom J, Salvador LM, Maizels ET, Reierstad S, Park Y, Carr DW, Davare MA, Hell JW, Palmer SS, Dent P, Kawakatsu H, Ogata M, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Follicle-stimulating hormone activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase but not extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase through a 100-kDa phosphotyrosine phosphatase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:7167–7179. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203901200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MA, Zhu Q, Unterman TG, Hammond JM. Follicle-stimulating hormone promotes nuclear exclusion of the forkhead transcription factor FoxO1a via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in porcine granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5585–5594. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JA, Cohen BD, Lindau-Shepard B, Nechamen CA, Peterson AJ, Schmidt A. Molecular, Structural, and Cellular Biology of Follitropin and Follitropin Receptor. In: Litwack G, editor. Vitamins and Hormones. 1 Ed. Academic Press; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 249–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsad K, Ringstad N, Takei K, Floyd SR, Rose K, De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon AW, Kallal L, Benovic JL. Role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in agonist-induced down-regulation of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273:6976–6981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Robayna IJ, Falender AE, Ochsner S, Firestone GL, Richards JS. Follicle-Stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) and serum and glucocorticoid- lnduced kinase (Sgk): evidence for A kinase-independent signaling by FSH in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1283–1300. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.8.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermann B. The BAR-domain family of proteins: a case of bending and binding? The membrane bending and GTPase-binding functions of proteins from the BAR-domain family. Embo Reports. 2004;5:250–255. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and beta-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18677–18680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindau-Shepard BA, Brumberg HA, Peterson AJ, Dias JA. Reversible immunoneutralization of human follitropin receptor. J Reprod Immun. 2001;49:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(00)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yao F, Wu R, Morgan M, Thorburn A, Finley RL, Jr., Chen YQ. Mediation of the DCC apoptotic signal by DIP13 alpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26281–26285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204679200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttrell LM, Roudabush FL, Choy EW, Miller WE, Field ME, Pierce KL, Lefkowitz RJ. Activation and targeting of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2449–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041604898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maizels ET, Cottom J, Jones JC, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) activates the p38 mitogen- activated protein kinase pathway, inducing small heat shock protein phosphorylation and cell rounding in immature rat ovarian granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3353–3356. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A, Shevchenko A, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Habermann B, Wilm M, Parton R, Zerial M. APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell. 2004;116:445–456. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuuchi Y, Johnson SW, Moonblatt S, Testa JR. Translocation and activation of AKT2 in response to stimulation by insulin. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1998;70:433–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuuchi Y, Johnson SW, Sonoda G, Tanno S, Golemis EA, Testa JR. Identification of a chromosome 3p14.3-21.1 gene, APPL, encoding an adaptor molecule that interacts with the oncoprotein-serine/threonine kinase AKT2. Oncogene. 1999;18:4891–4898. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechamen CA, Dias JA. Point mutations in follitropin receptor result in ER retention. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;201:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechamen CA, Thomas RM, Cohen BD, Acevedo G, Poulikakos PI, Testa JR, Dias JA. Human follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor interacts with the adaptor protein APPL1 in HEK 293 cells: Potential involvement of the PI3K pathway in FSH signaling. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:629–636. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter BJ, Kent HM, Mills IG, Vallis Y, Butler PJ, Evans PR, McMahon HT. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringstad N, Nemoto Y, De Camilli P. Differential expression of endophilin 1 and 2 dimers at central nervous system synapses. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40424–40430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106338200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvador LM, Flynn MP, Avila J, Reierstad S, Maizels ET, Alam H, Park Y, Scott JD, Carr DW, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Neuronal microtubule-associated protein 2D is a dual a-kinase anchoring protein expressed in rat ovarian granulosa cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27621–27632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402980200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ED, Nunez G, Barr FG, Guan KL. Negative regulation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR by Akt. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16741–16746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarricone C, Xiao B, Justin N, Walker PA, Rittinger K, Gamblin SJ, Smerdon SJ. The structural basis of Arfaptin-mediated cross-talk between Rac and Arf signalling pathways. Nature. 2001;411:215–219. doi: 10.1038/35075620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vondriska TM, Pass JM, Ping P. Scaffold proteins and assembly of multiprotein signaling complexes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;37:391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W, Scott JD. AKAP signalling complexes: focal points in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:959–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Lin HK, Altuwaijri S, Xie S, Wang L, Chang C. APPL suppresses androgen receptor transactivation via potentiating Akt activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16820–16827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, Roy SK. Follicle stimulating hormone-induced DNA synthesis in the granulosa cells of hamster preantral follicles involves activation of cyclin-dependent kinase-4 rather than cyclin d2 synthesis. Biol Reprod. 2004;70:509–517. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.023457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]