Abstract

The primary Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection occurs in the oropharynx, where the virus infects B cells and subsequently establishes latency in the memory B-cell compartment. EBV has previously been shown to induce changes in the cell surface expression of several chemokine receptors in cell lines and the transfection of EBNA2 or LMP1 into a B-cell-lymphoma-derived cell line decreased the expression of CXCR4. We show that in vitro EBV infection reduces the expression of CXCR4 on primary tonsil B cells already 43 hr after infection. Furthermore, EBV infection affects the chemotactic response to stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1)α/CXCL12, the ligand for CXCR4, with a reduction of SDF-1α-induced migration. To clarify whether this reduced migration is EBV-specific or a consequence of cell activation, tonsillar B cells were either infected with EBV, activated with anti-CD40 and interleukin-4 (IL-4) or kept in medium. Activation by anti-CD40 and IL-4 decreased the CXCR4 expression but the CD40 + IL-4-stimulated cells showed no reduction of chemotactic efficacy. Our finding suggests that changing the SDF-1α response of the EBV-infected B cells may serve the viral strategy by directing the infected cells into the extrafollicular areas, rather than retaining them in the lymphoepithelium.

Keywords: B cells; chemokines; Epstein–Barr virus: migration, traffic, circulation; monokines

Introduction

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous B-lymphotropic human γ-herpesvirus, which establishes a lifelong latency in the memory B-cell compartment.1 In childhood the infection is asymptomatic while in adolescence it can cause infectious mononucleosis (IM), an EBV-driven self-limiting lymphoproliferative disorder.2 The virus is also associated with a number of malignancies such as Burkitt lymphoma, nasopharyngeal cancer and immunoblastomas arising in patients who are immunodefective for genetic (X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome), iatrogenic (organ transplantation) or infectious (human immunodeficiency virus) reasons (for review see ref. 3).

EBV infection occurs in the oropharynx where the virus infects tonsillar B cells either directly or through transient infection of the crypt epithelium.4,5 Interestingly, in tonsils from patients with IM most EBV-positive B cells are located in the extrafollicular areas, including the crypt epithelium, and only a few EBV-carrying cells can be detected in the germinal centres (GC) of these tonsils.6,7 From studies in mice, it has been suggested that EBV-infected B cells may be prevented from entry to the GC, as suggested by the prevention of GC formation in transgenic mice expressing latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) in B cells.8 In latent infection, distinct EBV gene expression patterns have been described (for review see ref. 3). In vivo, latency III is found in infected B cells that are driven to proliferate by the virus. In latency III, nine virally encoded proteins, six nuclear proteins (Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) to EBNA6), three membrane bound proteins, LMP1, LMP2A and LMP2B, and the small non-polyadenylated RNAs [EBV encoded RNAs (EBERs)] are expressed. More restricted viral gene expression is also observed during certain conditions. Latency II, characterized by expression of EBERs, EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A and LMP2B, is found in non-immunoblastic malignancies like Hodgkin's disease and nasopharyngeal cancer. Latency I is found in cells from Burkitt lymphoma patients ex vivo and these cells only express EBNA1 and EBERs. In healthy seropositive individuals the infected cells are mainly of resting phenotype, expressing no EBV-encoded proteins, or occasionally LMP2a and/or EBNA1 transcripts, i.e. latency 0.9 Studies of the lymphoreticular tissue in primary EBV infection (IM) have shown infected cells in latency III, II and 0/I.7

Over the past decade chemokines have been shown to play an important role in inflammation, haematopoiesis, tumour growth and several other pathological conditions. Chemokines represent a super-family of small, cytokine-like proteins that interact with G-protein coupled receptors and induce cytoskeletal rearrangement, adhesion to endothelial cells and directional migration.10 Several herpes viruses have been found to encode chemokines and/or chemokine receptor genes that may affect host immune responses and viral tissue tropism, thus contributing to viral pathogenesis.11,12 It has been shown that EBV induces changes in the expression of receptors for chemokines and surface-adhesion molecules in lymphoblastoid cell lines. 13–15 The virus can modulate the expression of certain chemokine receptors, such as CXCR4, CXCR5, CCR6 and CCR10. In the B-cell-lymphoma-derived line BJAB, transfection of EBNA2 or LMP1, decreased the expression of CXCR4.13

The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is found on many cell types including B and T cells, astrocytes and epithelial cells in the lung, kidney and liver.16 In humans, CXCR4 is highly expressed on progenitor cells in the bone marrow and especially on cells committed to the B-cell lineage.17,18 Under normal conditions, the most important function of CXCR4 is to retain immature cells in the bone marrow for further maturation.19,20 However, CXCR4 and its ligand, stromal cell-derived factor (SDF-1)/CXCL12 also play a role in the periphery where SDF-1α is present in lymphoid tissue together with several other chemokines.21 These chemokines and their respective ligands recruit cells of the immune system to the lymphoid tissue and retain them within the appropriate supportive microenvironment. Recently, Allen and colleagues reported that GC organization is disrupted in mice that are deficient in CXCR4.22 In this model, it was shown that proper localization of the GC dark zone is dependent on the expression of CXCR4 by B cells.

To better understand how primary EBV infection may alter chemotactic responses we have investigated the expression of CXCR4 and the response to SDF-1α early after in vitro EBV infection. Our results show that EBV gradually down-regulates the expression of CXCR4 and by day 13 after infection the expression is minimal. However, the ability to migrate in response to SDF-1α is already decreased 2 days after infection. Furthermore, the frequency of EBV-positive cells in the migrated population is lower compared with the non-migrating fraction, indicating that the EBV-carrying cells migrate less well in response to SDF-1α.

Materials and methods

B-cell preparation

Tonsils were obtained from routine tonsillectomy after the informed consent of the patients at the Karolinska University Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden). Human tonsils were cut into fragments and dispersed into cell suspensions. T cells were removed by E rosetting followed by separation on Lymphoprep (Axis-Shield PoC AS, Oslo, Norway). The remaining cells were suspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS, Gibco, Paisley, UK), glutamine (2 mm), penicillin and streptomycin. These cells contained > 92% CD19-positive cells.

Cell culture

All cultures were carried out in HEPES-buffered RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, glutamine (2 mm), penicillin and streptomycin. For activation, B cells were cultured at 1 × 106/ml in medium alone or together with a mouse monoclonal antibody to CD40 (Nordic Biosite, Täby, Sweden) (1 μg/ml) and interleukin-4 (IL-4; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) (5 ng/ml) for 41–45 hr. For EBV infection, B cells were incubated with B95-8 supernatant, a substrain of EBV. After 1 hr the virus was washed away and medium containing 10% FCS was added at a concentration of 1 ml/106 cells.

Flow cytometry studies

The following monoclonal antibodies were used: phycoerythrin (RPE)-conjugated anti-CXCR4 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), RPE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD19 and the negative isotype-matched control RPE-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G2a (DAKO, A/S, Glostrup, Denmark).

One million cells were incubated with saturating amounts of monoclonal antibodies for 30 min, at room temperature (CXCR4) or + 4° (CD19). After washing, the cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analysed in a FACScan using cell quest software (Becton Dickinson, Stockholm, Sweden). The control and infected populations were gated according to size [forward scatter (FSC)] and CXCR4 expression. When analysing the mean fluorescence intensity (mFI) for CXCR4 expression, the results are presented as mFI for CXCR4 expression after subtraction of mFI for the isotype-matched control antibody.

EBNA staining

Smears were prepared in a cytospin (Shandon IV), at 113 g, for 5 min. The slides were then stored in acetone : methanol (1 : 1) at −20° until staining. After rehydration for 20 min the samples were stained for total EBNA using anti-complement immunofluorescence.23 Primary antibody from an EBV sero-positive donor, complement from an EBV sero-negative donor and fluorescein-isothiocyanante-labelled rabbit anti-human C3c (DAKO) were used for the staining. Viability of cells was determined by DNA staining (bisbenzimide, Hoechst 33258, Hoechst BDH, Poole, UK) or counterstaining by Evans blue (BDH, Poole, UK).

Transmigration assay

A Transwell culture system was performed in duplicate on primary tonsillar B cells using filters with 5-μm pore diameter (Transwell, 24-well plate, Costar, Cambridge, MA) as previously described.24 The cells (2·5 × 105) were resuspended in 100 μl RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% FCS, 2 mm glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin and then loaded into the upper chamber of the Transwell filter. To examine the SDF-1α-induced migration, 600 μl medium containing 250 ng/ml recombinant SDF-1α (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added to the lower well and the plate was incubated at 37° for 4 hr. Thereafter, the migrated cells in the lower wells (and when appropriate the non-migrating cells in the upper chambers) were collected. Migrated cells were fixed with 200 μl 1% formaldehyde in PBS and counted in a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For EBNA-staining, both the migrated and non-migrating cells were collected, and the percentage of EBNA-positive cells was determined.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with the software graphpad prism (GraphPad Software Inc, San Diego, CA). Differences in expression of CXCR4 and EBNA between the uninfected and EBV-infected tonsillar B cells were analysed using the Mann–Whitney test.

Results

CXCR4 expression early after infection

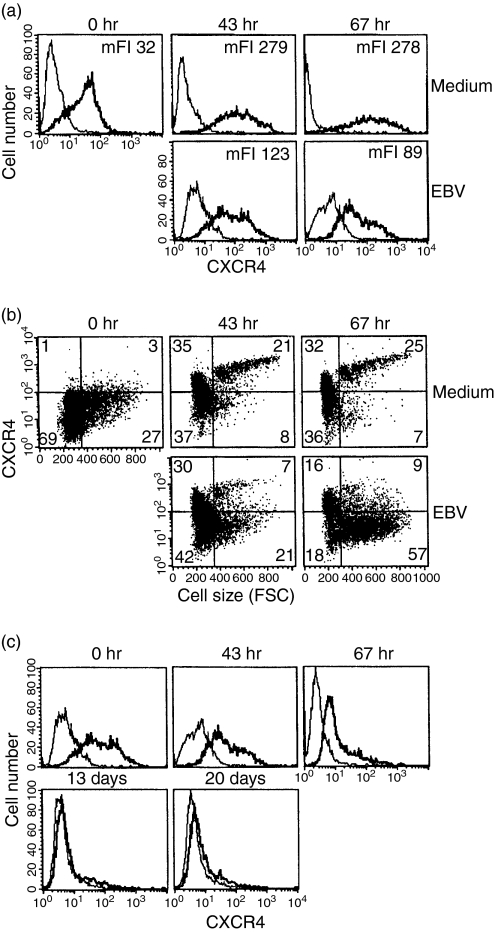

To study CXCR4 expression early after infection, tonsil B lymphocytes were infected and harvested after 43 and 67 hr. At 43 hr after infection, the expression of CXCR4 in the infected cells was decreased compared to uninfected cells cultured under the same conditions (Fig. 1a). After 67 hr the expression had further decreased in the infected population whereas the uninfected cells showed an increased level of CXCR4. At these time-points, the total EBNA expression was 35% and 52%, respectively. During primary EBV infection, the extent of the cells' size increase due to activation and the expansion of this cell population can be monitored by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1(b) the gates were set to identify resting and activated cells by analysing cell size (FSC). In these large EBV-infected cells the expression of CXCR4 was lower than in the uninfected controls (Fig. 1b). The infected population was kept in culture for an additional 2 weeks and the expression of CXCR4 was monitored at days 6, 13 and 20. The CXCR4 expression was further decreased by day 6 and by day 13 expression was almost totally absent (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

CXCR4 expression after EBV infection of tonsillar B cells. (a) CXCR4 expression was monitored in infected tonsillar B cells at 0 hr, and then at 43 hr and 67 hr when 35% and 52% of the cells, respectively, expressed EBNA. (b) The results are presented as dot plots to display CXCR4 expression vs. cell size. (c) The CXCR4 expression in the infected population was followed until day 20 after infection. Representative data of three independent experiments are shown. The last three time-points in (c) were followed in two experiments. The bold line represents the specific staining and the thin line represents staining with isotype-matched control.

SDF-1α-induced migration of infected cells

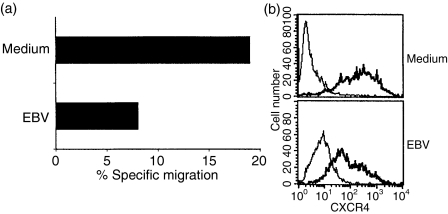

To investigate whether the decrease in CXCR4 expression altered the ability to respond to SDF-1α in a chemotaxis assay, tonsil B cells were harvested after 45 hr and the chemotactic response of the infected and control cells was compared. In the infected culture 64% of the cells expressed EBNA. EBV-infected tonsillar B cells had a lower ability to migrate in response to SDF-1α (8%), than their uninfected counterparts (18%) (Fig. 2a). The infected population showed decreased expression of CXCR4 as compared with cells cultured in medium but almost all cells still expressed the receptor (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Chemotactic response of tonsillar B cells to SDF-1α. (a) Tonsillar B cells were infected with EBV. The chemotactic response induced by SDF-1α in infected and control cells was compared after 45 hr in a 4-hr Transwell migration assay. The result is presented as percentage of migrated cells compared to input population after subtraction of background migration to medium. (b) CXCR4 expression in infected and control cells 45 hr after infection. The infected population contained 64% EBNA-positive cells. Representative data of three independent experiments are shown. The bold line represents the specific staining and the thin line staining with isotype-matched control.

EBNA expression of migrated cell

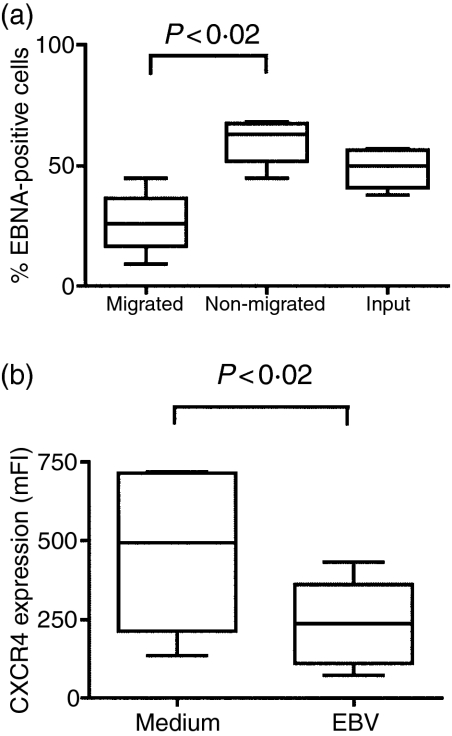

Fewer EBV-infected cells migrated in response to SDF-1α 45 hr after infection, than the cells cultured in medium only. To investigate whether it was EBNA-positive cells in the infected cultures that were responsible for the lower chemotactic activity, migration assays were undertaken followed by cell staining. Migrated and non-migrated cell fractions from each well were collected and stained for EBNA. The percentage of EBNA-positive cells in the migrated fractions was lower than in the total input population, thereby indicating that EBV-infected cells have a reduced capacity for SDF-1α-induced migration (Fig. 3a). Consistent with this, the non-migrated fraction showed an increased percentage of EBNA-positive cells compared to the input populations (Fig. 3a). The control (uninfected) cells expressed no EBNA, as expected. The level of CXCR4 expression on the EBV-infected populations was decreased compared to the control cells although the majority still readily expressed the receptor (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

EBNA expression in SDF-1α responding and non-responding tonsillar B cells. (a) Transwell migration assays were performed 41–45 hr after infection. After 4-hr incubation the cells that did or did not respond to the ligand were harvested separately and checked for EBNA expression (n = 4). (b) CXCR4 expression 41–45 hr after infection in infected and control cells. Statistics are based on the experiments shown in Figs 2, 3 and 4 (n = 6).

Comparison of EBV and CD40 + IL-4-activated tonsillar B cells

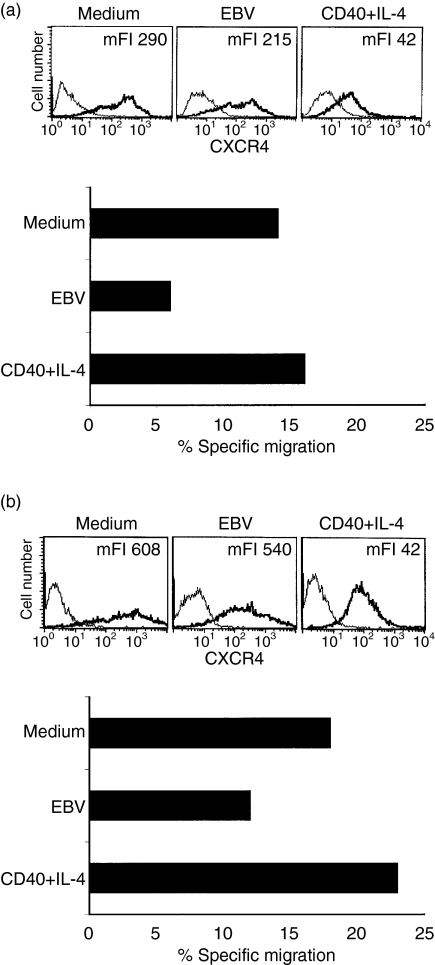

The finding that EBV modulates the migration to SDF-1α raised the question whether this effect is EBV-specific or a consequence of cell activation. Therefore, tonsillar B cells were either EBV infected, activated with anti-CD40 and IL-4 or kept in medium. In two independent experiments the different populations were harvested after 42 hr and 47 hr, respectively, and were subsequently incubated with SDF-1α. CXCR4 staining confirmed the finding that EBV infection decreased the level of CXCR4 expression compared to cells cultured with medium alone (Fig. 4a,b, upper panel). Furthermore, CD40 + IL-4-activated cells showed an even lower receptor density (Fig. 4a,b, upper panel).

Figure 4.

Comparison of the chemotactic response to SDF-1α after EBV infection or ligation of CD40 + IL-4 in tonsillar B cells. In two independent experiments tonsillar B cells were infected with EBV, activated through ligation of CD40 + IL-4 or kept in medium. After 42 hr and 47 hr, respectively, the different cell populations were harvested and tested for CXCR4 expression and subsequently monitored in a 4-hr Transwell migration assay for the response to SDF-1α. In the upper panels of (a) and (b) the CXCR4 expression in the different cultures is shown. The bold line represents the specific staining and the thin line represents staining with isotype-matched control. The results of the migration assay are shown in the lower panels as percentage of migrated cells compared to input cells after subtraction of background migration. The infected population contained 40% and 50% EBNA, respectively.

Despite the lower receptor density, CD40 + IL-4-activated cells showed no decrease in their ability to migrate in response to SDF-1α compared to the control cells whereas EBV infection reduced the number of migrating cells (Fig. 4a,b, lower panel). The infected input population contained 40% (Fig. 4a) and 50% (Fig. 4b) EBNA-positive cells, respectively.

Discussion

The primary target for EBV infection is the B lymphocytes and following immunoblastic transformation and expansion of these cells the virus persists in the memory compartment.1 The virally encoded proteins EBNA2 and LMP1 have been shown to down-regulate CXCR4 in BJAB, a B-cell-lymphoma line.13 This raised the question whether EBV modulates the CXCR4 expression of newly infected tonsil B lymphocytes as well, and thereby influences their chemotactic response.

To approach that question, we tested the expression of CXCR4 at different time-points after infection and found a gradual decrease with time, in comparison to cells cultured in medium. The increase of the CXCR4 expression seen in the uninfected cells cultured with medium for 43 hr compared to that seen in cells stained immediately after preparation has previously been described by Brandes et al.25 Conceivably, EBV might infect cells with a variable expression of CXCR4 but subsequently down-regulate the receptor in the established lymphoblastoid cell lines. Alternatively, the virus might infect cells with a moderate CXCR4 expression and prevent the induction of the receptor to the same high level as in the control cells.

We then asked whether the change in CXCR4 expression in the infected population also affected the chemotactic response to the SDF-1α ligand. SDF-1α can induce migration in tonsillar naive and memory B cells.24 The uninfected cells migrated at the same magnitude previously reported.25 However, the infected cells migrated less well than the controls although almost all cells expressed the receptor at this early time-point after EBV infection. This indicates that the ability to respond to SDF-1α is reduced in EBV-carrying immunoblasts. In line with this hypothesis, we found that the population migrating in response to SDF-1α contained fewer EBNA+ cells than the non-migrating cell fraction. This finding indicates that EBV modulates the SDF-1α-induced migration of tonsillar B cells even though the receptor is expressed.

The decrease in SDF-1α-induced chemotaxis may be the result of conformational changes of CXCR4. In primary B cells the receptor shows considerable conformational heterogeneity.26 Recently Fernandis and collaborators27 showed that the membrane tyrosine phosphatase, CD45 differentially regulates CXCR4-mediated chemotactic activity and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in T cells by modulating the activities of focal adhesion components and downstream targets of the T-cell receptor. Whether this applies for B cells is not known.

Ligation of the B-cell receptor has previously been shown to decrease SDF-1α-induced migration and this reduction is more pronounced upon CD40 ligation.24 However, activation by CD40 ligation does not reduce the SDF-1α response in itself.24 Increased migration of peripheral B lymphocytes after stimulation with anti-CD40 plus IL-4 has previously been reported25 with an enhancement of the chemotactic ability at 36 hr and the specific migration returning to background levels after 72 hr. Therefore, we compared the chemotactic ability 42 hr after either EBV infection or CD40 ligation + IL-4. The decrease of migration in the infected population was confirmed whereas the CD40 + IL-4-stimulated cells showed no reduction of chemotactic efficacy. The expression of CXCR4 decreased in both the EBV-infected and CD40 + IL-4-activated population but was more pronounced in the latter. The difference in response to SDF-1α between EBV-infected cells and cells activated by CD40 + IL-4 cannot be explained by expression of adhesion molecules like CD11a/CD18 and CD54. These adhesion molecules are up-regulated both by EBV and CD40 + IL-4.15,28 Clearly, SDF-1α-induced migration can be modulated in ways other than the down-regulation of the receptor, as already discussed.

Viruses have evolved strategies to modulate chemokine activities through production of viral chemokine receptors, viral chemokines and viral chemokine binding proteins (for review see ref. 29). Interestingly, after infection in vitro of human monocytes by influenza A virus, unresponsiveness to CCL2-induced migration precedes the down-regulation of the corresponding receptor, CCR2. This dissociation between receptor expression and chemotactic response occurs already 3 hr after infection.30 EBV encodes at least two cytokine-related homologues, viral IL-10 and a soluble colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor29 but no chemokine-associated viral proteins have yet been detected in humans. However, several human herpes viruses have been found to encode chemokine receptor genes and these receptors have also been found to bind known chemokines, mediating a functional response.12,31

SDF-1α production has been detected in the crypts and outer epithelium of the tonsil.21 This is often considered as the most likely primary site of EBV persistence, and may also be the site of virus entry.32 All SDF-1α-producing cells coexpress cytokeratin-19 indicating an epithelial phenotype.21 This suggests a possible involvement of SDF-1α in recruiting and retaining B cells at the site where antigen can be encountered, such as the crypt epithelium.8 Furthermore, Bleul et al.24 detected message for SDF-1 in the connective tissue that forms the stationary scaffold surrounding the GCs. A change in the SDF-1α response of B cells after primary EBV infection may serve the viral strategy by permitting the infected cells to migrate into the extrafollicular areas, rather than to be retained in the lymphoepithelium through the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis. Recently, it has been reported that CXCR4-deficient mice show an altered GC organization.22 Lethally irradiated mice were reconstituted with wild-type CXCR4+/+ or CXCR4−/− fetal liver chimeras. After immunization with a GC-inducing antigen, analysis of the spleens from CXCR4−/− mice showed a disrupted GC organization compared to spleens from the CXCR4-expressing wild-type.22 Our data may indicate that EBV-induced down-regulation of CXCR4 on infected B cells may account for the lack of EBV-positive B cells in the GC of tonsils from IM patients as previously reported.33 This hypothesis is supported by the observation that EBV-infected B cells expanding in the GCs of IM patients do not participate in the GC reaction because no ongoing somatic hypermutation could be detected.6 CXCR4 down-regulation may be one step in the change of the GC formation induced by LMP1. This is consistent with the observation that, extrafollicular B-cell differentiation occurs in LMP1 transgenic mice, with a concomitant block in the GC formation.

In conclusion, a change in the SDF-1α response of EBV-infected B cells may serve the viral strategy of directing the infected cells into the extrafollicular areas, rather than retaining them in the lymphoepithelium.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Francesca Chiodi for fruitful discussions and for her critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Mia Löwbeer for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by The Swedish Cancer Society and The Swedish Children Cancer Foundation.

Abbreviations

- EBV

Epstein–Barr virus

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- GC

germinal centre

- IL-4

interleukin 4

- IM

infectious mononucleosis

- mFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor

References

- 1.Babcock GJ, Decker LL, Volk M, Thorley-Lawson DA. EBV persistence in memory B cells in vivo. Immunity. 1998;9:395–404. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henle W. Evidence for viruses in acute leukemia and Burkitt's tumor. Cancer. 1968;21:580–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196804)21:4<580::aid-cncr2820210406>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rickinson AM, Kieff E. Epstein–Barr virus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2575–628. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chodosh J, Gan Y, Holder VP, Sixbey JW. Patterned entry and egress by Epstein–Barr virus in polarized CR2-positive epithelial cells. Virology. 2000;266:387–96. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sixbey JW, Nedrud JG, Raab-Traub N, Hanes RA, Pagano JS. Epstein–Barr virus replication in oropharyngeal epithelial cells. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1225–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405103101905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurth J, Hansmann ML, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R. Epstein–Barr virus-infected B cells expanding in germinal centers of infectious mononucleosis patients do not participate in the germinal center reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2627966100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niedobitek G, Agathanggelou A, Herbst H, Whitehead L, Wright DH, Young LS. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection in infectious mononucleosis. Virus latency, replication and phenotype of EBV-infected cells. J Pathol. 1997;182:151–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199706)182:2<151::AID-PATH824>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida J, Yasui T, Takaoka-Shichijo Y, Muraoka M, Kulwichit W, Raab-Traub N, Kikutani H. Mimicry of CD40 signals by Epstein–Barr virus LMP1 in B lymphocyte responses. Science. 1999;286:300–3. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hochberg D, Middeldorp JM, Catalina M, Sullivan JL, Luzuriaga K, Thorley-Lawson DA. Demonstration of the Burkitt's lymphoma Epstein–Barr virus phenotype in dividing latently infected memory cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2237267100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature. 1998;392:565–8. doi: 10.1038/33340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camarda G, Spinetti G, Bernardini G, Mair C, Davis-Poynter N, Capogrossi MC, Napolitano M. The equine herpesvirus 2, E1 open reading frame encodes a functional chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1999;73:9843–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9843-9848.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isegawa Y, Ping Z, Nakano K, Sugimoto N, Yamanishi K. Human herpesvirus 6 open reading frame U12 encodes a functional beta-chemokine receptor. J Virol. 1998;72:6104–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.6104-6112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama T, Fujisawa R, Izawa D, Hieshima K, Takada K, Yoshie O. Human B cells immortalized with Epstein–Barr virus upregulate CCR6 and CCR10 and downregulate CXCR4 and CXCR5. J Virol. 2002;76:3072–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.6.3072-3077.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rincon J, Prieto J, Patarroyo M. Expression of integrins and other adhesion molecules in Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B lymphoblastoid cells and Burkitt's lymphoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;51:452–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang F, Gregory C, Sample C, Rowe M, Liebowitz D, Murray R, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein–Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes. EBNA-2 and LMP1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol. 1990;64:2309–18. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2309-2318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coulomb-L'Hermin A, Amara A, Schiff C, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and antenatal human B cell lymphopoiesis: expression of SDF-1 by mesothelial cells and biliary ductal plate epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8585–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aiuti A, Tavian M, Cipponi A, Ficara F, Zappone E, Hoxie J, Peault B, Bordignon C. Expression of CXCR4, the receptor for stromal cell-derived factor-1 on fetal and adult human lympho-hematopoietic progenitors. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1823–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199906)29:06<1823::AID-IMMU1823>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohle R, Bautz F, Rafii S, Moore MA, Brugger W, Kanz L. The chemokine receptor CXCR-4 is expressed on CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells and mediates transendothelial migration induced by stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 1998;91:4523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Q, Jones D, Springer TA. The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is required for the retention of B lineage and granulocytic precursors within the bone marrow microenvironment. Immunity. 1999;10:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin JB, Kung AL, Klein RS, et al. A small-molecule antagonist of CXCR4 inhibits intracranial growth of primary brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13513–18. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235846100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casamayor-Palleja M, Mondiere P, Amara A, Bella C, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Caux C, Defrance T. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-3α, stromal cell-derived factor-1, and B-cell-attracting chemokine-1 identifies the tonsil crypt as an attractive site for B cells. Blood. 2001;97:3992–4. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen CD, Ansel KM, Low C, Lesley R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, Cyster JG. Germinal center dark and light zone organization is mediated by CXCR4 and CXCR5. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:943–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reedman BM, Klein G. Cellular localization of an Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) -associated complement-fixing antigen in producer and non-producer lymphoblastoid cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1973;11:499–520. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910110302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bleul CC, Schultze JL, Springer TA. B lymphocyte chemotaxis regulated in association with microanatomic localization, differentiation state, and B cell receptor engagement. J Exp Med. 1998;187:753–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandes M, Legler DF, Spoerri B, Schaerli P, Moser B. Activation-dependent modulation of B lymphocyte migration to chemokines. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1285–92. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.9.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baribaud F, Edwards TG, Sharron M, et al. Antigenically distinct conformations of CXCR4. J Virol. 2001;75:8957–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.19.8957-8967.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandis AZ, Cherla RP, Ganju RK. Differential regulation of CXCR4-mediated T-cell chemotaxis and mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by the membrane tyrosine phosphatase, CD45. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9536–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjorck P, Paulie S. Inhibition of LFA-1-dependent human B-cell aggregation induced by CD40 antibodies and interleukin-4 leads to decreased IgE synthesis. Immunology. 1993;78:218–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alcami A. Viral mimicry of cytokines, chemokines and their receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:36–50. doi: 10.1038/nri980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salentin R, Gemsa D, Sprenger H, Kaufmann A. Chemokine receptor expression and chemotactic responsiveness of human monocytes after influenza A virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:252–9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margulies BJ, Browne H, Gibson W. Identification of the human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor homologue encoded by UL33 in infected cells and enveloped virus particles. Virology. 1996;225:111–25. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorley-Lawson DA. Epstein–Barr virus: exploiting the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:75–82. doi: 10.1038/35095584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurth J, Spieker T, Wustrow J, Strickler GJ, Hansmann LM, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R. EBV-infected B cells in infectious mononucleosis: viral strategies for spreading in the B cell compartment and establishing latency. Immunity. 2000;13:485–95. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]