Abstract

Alloreactivity is one of the most serious problems in organ transplantation. It has been hypothesized that pre-existing alloreactive T cells are actually cross-reacting cells that have been primed by the autologous major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and a specific peptide. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes that are alloreactive and recognize a virus-peptide that is presented by the autologous MHC have been reported. Here we demonstrate a cross-reactivity that exists between DQ0602 restricted, herpes simplex type 2 VP16 40–50 specific CD4+ T-cell clones, which can be alloreactive to DQ0601. Though most of the DQ0602 restricted T-cell clones we isolated from two different donors were not alloreactive, weakly cross-reacting T-cell clones could be isolated from both donors. Two strongly cross-reacting T-cell clones with high affinity interaction of their T-cell receptor (TCR) with both DQ0602/VP16 40–50 and DQ0601 could be isolated from one donor. DNA sequencing of the a fragment of the Vβ gene used in their TCR confirmed that these two T cells indeed are two independent clones. These clones are cytotoxic and produce cytokines of a T helper 2-like pattern. Possible implications in a DR-matched transplantation setting are discussed.

Keywords: alloreaction, HLA-DQ, CD4, HSV-2, cross-reactivity

Introduction

Many T cells recognize foreign major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules either directly or indirectly by presentation of foreign MHC peptide on autologous MHC molecules. This alloreactivity is a major problem for organ transplantation as it can lead to acute, and possibly chronic, allograft rejection, ultimately causing organ failure. Poor human leucocyte antigen (HLA) matching of donor and recipient has a major impact on long-term graft survival.1 However, the structural requirements for alloreactivity of T cells are still poorly understood. The finding that stimulation of allorecognition by MHC-positive antigen-processing mutants is impaired, leads to the conclusion that direct allorecognition is peptide dependent, in the way that a specific endogenous peptide has to be present in the peptide-binding groove of the MHC molecule.2,3 Whether a specific peptide is a central part of the T-cell recognition in every case of allorecognition or whether it can be replaced by an arbitrary peptide is still under debate. Sometimes precursor frequencies of alloreactive T cells in patients that have not exposed to this alloantigen are so high, that it is likely that these T cells are previously expanded, promiscuous memory T cells. Steinle et al. detected a pre-existing expansion of B35 alloreactive T cells in a patient that has never been exposed to B35.4 They were not able to identify the autologous MHC/peptide complex that stimulated this T-cell clone. There is also evidence for a more important role of a specific peptide if the autologous and the allogenic MHC molecule are more closely related while allorecognition of a very distant MHC molecule is less peptide dependent.5 This finding can be explained by the conclusion of Huseby and coworkers that negative thymic selection is more likely to affect promiscuous, cross-reacting T cells, compared to more peptide specific ones.6,7 For some alloreactive T-cell clones, the peptide has been identified and the allorecognition is strictly dependent on this specific peptide.8–10 It is widely accepted that alloreactive T cells can be activated during viral infections.11–13 The hypothesis that alloreactive T-cell clones are restricted by the autologous MHC together with a specific peptide and cross-react with the allo-MHC presenting a different peptide was supported by the discovery of HLA-B14, B35, and B44 alloreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) clones. These clones were EBV specific when the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) peptide was presented by the autologous HLA-B8.14,15 A similar finding was reported by Koelle and coworkers, who found herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) specific, HLA-A*0201 restricted T-cell clones that cross-react with HLA-B44.16 The clinical relevance of these cross-reactions has not yet been well established, however. The combination of a B44 donor into a B8 recipient (which corresponds to a very common EBV specific cross-reaction) has been associated with reduced graft survival in renal transplantation.17 CD4+ T-cell clones have been reported only very rarely in this context.18 This might be more the result of the limited number of CD4+ T-cells in an antiviral response than to principal differences in the nature of alloreactivity of CD4+ T cells. Here we report of CD4+, DQ0602 (DQ0602, HLA class two dimer formed by the HLA DQA1*0102 α-chain and the DQB1*0602 β-chain)-restricted, HSV-2 VP16 specific T-cell clones isolated from two different patients with recurrent herpes lesions, that cross-react with DQ0601 in an alloreactive manner. Two of the isolated clones have high affinity towards DQ0602/VP16 and DQ0601, and produce Granzyme B and cytokines of a T helper 2-like pattern.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and donors

BLS-1 DQ0602 (DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602), and BLS-1 DQ0604 (DQA1*0102/DQB1*0604) are stably HLA-DQ0602, and DQ0604-transfected B-lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL) that have been previously described.19 B-LCLs #9065 TAB089 (DQA1*0103/DQB1*0601) and #9066 HHKB (DQA1*0103/DQB1*0603) are homozygous typing cell lines from the 10th International Histocompatibility Workshop and Conference (IHWC).20 HSV-2 VP16 40–50 specific, DQ0602 restricted T-cell clone (clone 44) was originally isolated from a HLA-DQ0602 patient with recurrent herpes lesions.21 Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from two different DR15/DQ0601(DQA1*0103/DQB1*0601) positive donors, and two different DQ0603 (DQA1*0103/DQB1*0603) positive donors. PBMCs were also obtained from two different HLA-DQ0602 subjects with recurrent herpes lesions.

Cell culture

The stably DQ-transfected BLS-1 lines were propagated in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 25 mm HEPES, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (all from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). The T-cell clone was propagated in the same medium lacking FCS, and supplemented with 10% pooled human serum and 32 U/ml native human interleukin (IL-2) (Hemagen, Columbia, MD).

Peptides

Peptides used corresponded to the sequence of the HSV-2 VP16 protein residues 40–50: RLSQAQLMPSP. The HSV-2 VP16 protein residues 369–379: NNYGSTIEGLL; and CLIP peptide, invariant chain residues 91–103: MRMATPLLMQALP were used as irrelevant peptides for negative controls. The peptides were synthesized with an Applied Biosystems 432 Peptide Synthesizer (Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosytems, Foster City, CA).

HLA-DQ0602 tetramers

Peptide loaded HLA-DQ0602 tetramers were produced as described elsewhere.21 Briefly, recombinant DQA1*0102 and DQB1*0602, in which the transmembrane domain was replaced by a leucine zipper, were produced in Drosophila S2 cells. BirA was used to biotinylate the specific sequence contained in the DQB1*0602 construct. The resulting biotinylated heterodimers were loaded with peptides for three days at 37° and conjugated to PE-labelled streptavidin to produce tetramers. Peptides used corresponded to the sequence of the HSV-2 VP16 protein residues 40–50. The HSV-2 VP16 protein residues369–379, and CLIP peptide, invariant chain residues 91–103 were used as irrelevant peptides for negative control tetramers.

Isolation of cross-reactive T-cell clones

Cryopreserved PBMC from two different DQ0602 positive patients with recurrent herpes lesions were incubated with 10 μm VP16 40–50 peptide. After 24 hr, 32 U/ml IL-2 were added and the cells were fed with fresh T-cell medium every 24–48 hr. Alternatively the PBMC were stimulated with irradiated PBMC from a DR15/DQ0601 positive donor. After 12 days, the cells were stained with a FITC labelled anti-CD4 antibody (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and PE-labelled DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramers. The cells were single cell sorted into 96 well plates using a FACSVantage cell sorter (Becton Dickinson). Single cells were stimulated with phytohaemagglutinin (PHA, 1 μg/ml) and 7·5 × 104 irradiated fresh PBMCs from an unrelated healthy donor. After 15 days, T cells from positive wells were transferred to 48-well plates and again stimulated with fresh, irradiated PBMC and PHA. Thiry-two U of human IL-2 were added after 24 hr and T cells were fed with T-cell medium containing IL-2 every 24–48 hr. Another 12 days later T-cell stimulation assays and tetramer staining were performed.

Flow cytometry

T-cells were stained for 3 hr at 37° with phycoerythrin (PE)-DQ0602-tetramers, which were loaded with a HSV-2 VP16 40–50 peptide in 50 μl reactions containing 16 µg/ml DQ0602 tetramers. As negative control for specific peptide-loaded DQ0602-tetramers, DQ0602 tetramers were loaded with either another VP16 peptide (VP16 369–379) or CLIP. All staining reactions were carried out in staining buffer (1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0·02% NaN3, and 0·2% FCS. The flow cytometry was carried out on a BD FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

T-cell proliferation assay

Assays were performed in triplicates as 150 μl reactions in 96-well plates. The DQ0602 expressing BLS-1 lines were used as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in peptide-specific assays. The cells were irradiated with 3 × 104 rad γ-radiation and used at a stimulator to responder ratio of 2·5 : 1. APCs were preincubated with 10 μm peptide for 2 hr, and previously washed T cells were added without removal of peptide. No Il-2 was added. For the evaluation of alloreactivity of clone 44, BLCLs were used as APC at a 2·5 : 1 stimulator to responder ratio. For newly established T-cell clones alloreactivity was measured as follows: 104 T cells were incubated with 7·5 × 104 irradiated fresh PBMC from two different DR15/DQ0601 positive healthy donors. After a 3-day incubation at 37°, 1 μCi 3H-thymidine/well was added. In some cultures 25 ml/well supernatant was removed for cytokine detection prior to the addition of 3H-thymidine. Cells were harvested and tritium uptake was measured after 15 hr further incubation.

Determination of T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ-gene usage

Total RNA was isolated using 2 × 106 PHA expanded T cells with the column based RNA-Easy procedure (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First strand cDNA syntheses were subsequently performed using the Ready-To-Go™ T-primed first strand kit (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). The cDNAs were used as targets in a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based TCR typing procedure to determine Vβ usage using a panel of 5′ validated Vβ gene primers and the 3′ corresponding constant region Cα E and Cβ F primers.22

DNA sequencing

Family specific Vβ-products were purified to remove excess PCR primers using a QIAquick® PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Sequencing was performed using the BigDye™ Version 3.0 sequencing kit according to the manufacturer (Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosytems). Four pmol of the specific Vβ 5′ primer or constant-3′ primer were used for sequencing the forward and reverse direction of the PCR product, respectively. The sequencing reactions were run on an ABI 377 stretch automatic sequencer (Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosytems).

Granzyme B enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT)

Granzyme B secretion of the T-cell clones was measured using a BD™ ELISPOT Human Granzyme B ELISPOT Set (BD Bioscience, San Diego CA) according to the manufacturer. Specifically, 104 T-cells/well were incubated in the ELISPOT-plate with 104 BLS-1 DQ0602 or TAB 089 BLCL cells as APC and 10, 1 and 0 μg/ml VP16 40–50 peptide for 24 hr prior to the assay. The ELISPOT membranes were analysed using an Immuno Spot Series 3 A analyser (Cellular Technology Ltd, Cleveland, OH).

Flow-cytometric cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of T-cell clones was measured using a CytoxiLux Kit (OncoImmunin Inc, Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, labelled target cells were stained with a fluorogenic caspase substrate to detect caspase activation using flow cytometry.

Cytokine detection

Cytokine were measured from the supernatant of the T-cell proliferation assays. Twenty-five ml was removed from each well at day 3 after setup of the proliferation assay and triplicates wells were combined to a total sample volume of 75 ml. Cytokine detection was performed using a Cytometric Bead Array Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer.

Results

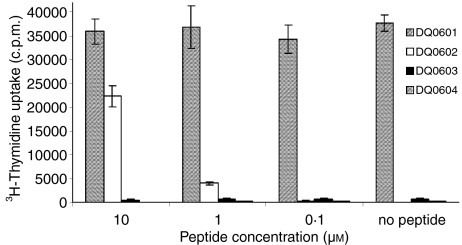

The HSV-2 VP16 40–50 epitope is a minor epitope in the antiviral response of DQ0602-positive patients with recurrent herpes lesions.21 The previously described T-cell clone 44 is specific to HSV-2 VP16 40–50 epitope when it is presented by DQ0602.19 A T-cell stimulation assay was set up with clone 44 and different DQ6 molecules as restriction element. Figure 1 shows that this T-cell clone can be stimulated in an alloreactive manner by DQ0601, but not by DQ0603 and DQ0604. This alloreactivity is independent of the presence of the VP16 40–50 peptide. The magnitude of the allo-response is directly proportional to DQ0601 cell numbers (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Proliferation of clone 44 in response to different concentrations of its cognate peptide HSV-2 VP16 40–50 presented by different HLA-DQ6 molecules. There is no proliferation seen with DQ0603 and DQ0604, a peptide dosage dependent proliferation with DQ0602, and VP16-peptide independent proliferation with DQ0601 as restriction element.

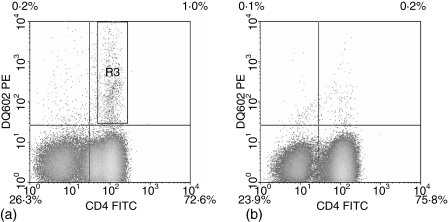

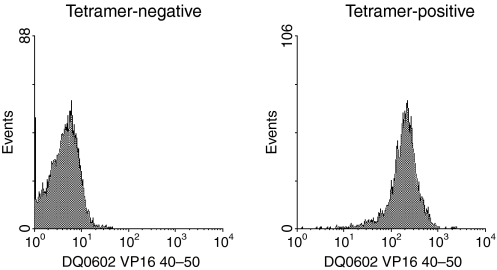

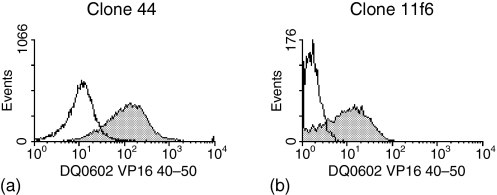

To evaluate the frequency of this type of cross-reactivity between DQ0602 restricted VP16 40–50 specific T cells and DQ0601, we developed a DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer-assisted T-cell cloning strategy; a single round of stimulation of PBMC from DQ0602 positive patients with recurrent herpes lesions was carried out using either VP16 40–50 peptide or irradiated PBMC from DQ0601-positive unrelated normal donors. Responding T cells were stained with a CD4 antibody and a PE-labelled DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer. In the bulk culture that had been stimulated with the VP16 40–50 peptide, a clear tetramer positive population was visible in the CD4+ population (Fig. 2a). This population was single-cell sorted and the same sort rectangle was used for bulk cultures that had been allo-stimulated with DQ0601-positive irradiated PBMC. In these cultures, however, the amount of tetramer-positive cells was not distinguishable from background staining obtained with a tetramer loaded with a control peptide or in the CD4 negative population (Fig. 2b). After expansion of the single cell sorted T-cells, the resulting T-cell clones were again stained with DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer. Proliferation after stimulation with DQ0601- and with DQ0602-positive APCs with and without VP16 40–50-peptide was measured using 3H-thymidine incorporation. From patient 1, 62 clones were raised in a single stimulation with VP16 40–50. The vast majority of these clones was tetramer positive (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Eighteen clones were raised from the same patient after a single stimulation with DQ0601 and DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer sorting. Only one of these clones (clone 11f6) showed strong staining with the DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer (Table 1 and Fig. 4). PBMC from patient 2 were treated exactly the same way, but only 18 T-cell clones in total could be isolated. Thirteen of these stem from an initial VP16 40–50 peptide stimulation, of which four showed a positive tetramer staining. The remaining five T-cell clones from this patient were cloned from a DQ0601-stimulated bulk PBMC culture and none of the clones was tetramer positive (Table 1). All of these clones were tested for their ability to proliferate after stimulation with DQ0602-positive APC and 10 μm VP16 40–50 peptide, DQ0602-positive APC alone or DQ0601-positive APC. Stimulation indices over five were considered positive. Most clones were able to proliferate with one of the stimuli, but only a few were able to proliferate significantly after both stimulations (Table 2). With the exception of one clone that was raised against DQ0601 designated 11f6, no cross-reactive T-cell clone was positive for DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer staining. DQ0602 tetramer staining and proliferation after stimulation with VP16 40–50 correlates in most but not all clones (Tables 1 and 2) in a fashion that all tetramer-positive clones proliferate after stimulation with VP16 40–50, but there are also tetramer-negative clones that proliferate.

Figure 2.

Tetramer staining of stimulated bulk PBMC cultures from HSV-2 positive patients. (a) VP16 40–50 stimulated culture. The rectangle in the upper right quadrant shows the approximate location of the sort rectangle that was used in the single cell sorts. (b) DQ0601 allo-stimulated culture. The difference in the number of tetramer-positive cells compared to (a) is clearly visible.

Table 1.

T-cell clones isolated from patients 1 and 2 and their staining properties with a DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer

| 1st round stimulation | Total number of isolated clones | DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer positive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | VP16 40–50 | 62 | 49 |

| DQ0601 | 18 | 1 | |

| Patient 2 | VP16 40–50 | 13 | 4 |

| DQ0601 | 5 | 0 |

Freshly isolated PBMC were stimulated using allo (DQ0601) or viral antigen (DQ0602/VP16 40–50) stimuli.

Figure 3.

DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer staining. The cells were gated on viable CD4+ cells. The left image shows a tetramer-negative, the right image a tetramer-positive clone.

Figure 4.

PE-DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer staining of the two tetramer-positive and strongly DQ0601 alloreactive clones.

Table 2.

T cell clones isolated from patient 1 and 2 and their specificity

| 1st round stimulation | Total number of clones | Proliferating after stimulation with DQ0602/VP16 40–50 (HSV peptide specific) | Proliferating after stimulation with DQ0601 (allospecific) | Proliferating after either stimulation (HSV peptide andallospecific)/tetramer positive* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | VP16 40–50 | 48 | 62 | 48 | 1/0 |

| DQ0601 | 18 | 2 | 7 | 2/1 | |

| Patient 2 | VP16 40–50 | 13 | 4 | 1 | 1/0 |

| DQ0601 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1/0 |

This column shows the number of cross reactive clones and how many of these can be stained with a DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer, which is a measure for high affinity.

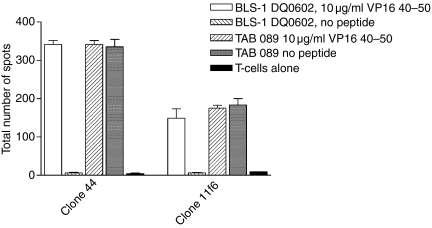

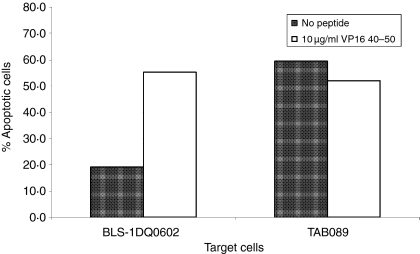

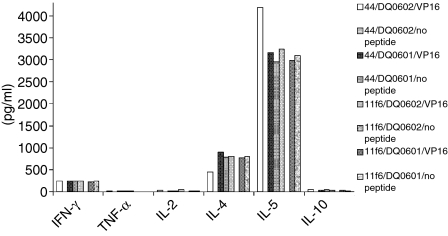

The original cross-reactive clone 44 was isolated from a sample from patient 1 that was taken at a different time point than the sample for the clones from Tables 1 and 2. However, it is possible that this clone persisted in the patient and was identical to the tetramer positive clone 11f6 that was isolated after initial stimulation with DQ0601. To test this hypothesis, Vβ family typing was done with clone 44 and clone 11f6. Both clones used genes from the Vβ 6 family. It is very common for T cells that are specific for the same antigenic epitope to also use the same Vβ gene family in their TCR, so sequencing of the specific Vβ gene PCR product was performed. Comparing the two sequences show that the CDR3 regions of clone 44 and clone 11f6 were different (Fig. 5). Further phenotypic characterization of clone 44 and 11f6 was performed to investigate cytokine secretion and cytotoxic properties of these clones. Both clones showed secretion of Granzyme B when the T cells were stimulated with DQ0602 expressing BLS-1 DQ0602 and VP16 40–50 peptide. DQ0601-expressing BLCL TAB089 could elicit Granzyme B secretion in the absence of the VP16 peptide in both clones (Fig. 6). To confirm that the clones indeed have cytotoxic activity, cytotoxicity was measured using flow cytometry. Target cells (TAB089 and BLS-1 DQ0602) stained with a vital dye, were incubated with the T cells and stained with a fluorogenic caspase substrate. Caspase activation showed induction of apoptosis. Both clones were able to induce apoptosis in TAB089 independent of the presence of VP16 40–50 peptide, while BLS-1 DQ0602 were only lysed in the presence of VP16 40–50 (Fig. 7). Cytokine secretion of clones 44 and 11f6 was measured using a cytometric bead array for human Th1/Th2 cells. Both clones produce cytokines of a Th2-like pattern: large amounts of IL-5, IL-4, and some interferon-g (IFN-γ), independently of the method of stimulation (Fig. 8).

Figure 5.

Identical amino acids are symbolized by an asterisk in the clone 11f6 sequence. Dashes mark a deletion in the clone 44 sequence.

Figure 6.

Granzyme B assays with T-cell clones 44 and 11f6 were done in triplicate. BLS-1 DQ0602 and TAB 089 were used as APCs with or without peptide, respectively.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxicity of clone 44. Cytotoxicity of clone 44 was evaluated by using a flow cytometry assay based on cleavage of a flurogenic caspase substrate within the target cells. T cells were incubated with dye-loaded BLS-1 DQ0602 or TAB089 cells at a 1 : 1 ratio in the presence and absence of 10 µg/ml VP16 40–50 peptide. Apoptotic target cells are shown as percentage of total dye loaded target cells.

Figure 8.

Cytokines were measured form the supernatant of a proliferation assay using cytometric bead arrays for human Th1/Th2 cytokines. Black and white patterned bars are from clone 44, black and grey from clone 11f6. Similarly to the proliferation results, no cytokine expression was detected with DQ0602 as restriction element in the absence of VP16 40–50 peptide, while cytokine production was independent of externally added peptide with DQ0601 as restriction element.

Discussion

Serendipitously, we had found that one of our DQ0602 restricted, HSV-2 VP16 40–50 specific T-cell clones recognizes DQ0601 in a peptide independent, alloreactive manner. Because this alloreaction might also occur in vivo in recipients of DR-matched, DQ-mismatched donor organs, we investigated how common this type of alloreactivity is in patients with recurrent herpes lesions. Pre-existing alloreactivity in people that have never been exposed to the alloantigen has long been an immunological mystery. This type of alloreactivity seems to be more common than previously recognized. The view is now widely accepted that at least a part of these alloreactive T-cell clones are memory T cells that cross-react with viral antigens presented by the endogenous MHC (for review see 23). The fact that promiscuous, pathogen-specific T cells can provide T-cell immunity for several different antigens that the host has been not pre-exposed to, has been called heterologous T-cell immunity and seems to be the underlying cause of pre-existing alloreactive memory T cells.24,25 Memory T cells are less dependent on costimulation and less susceptible to activation-induced cell death. It has been reported that this is the reason for the failure of tolerance-inducing protocols, that are successful in naïve mice, to induce tolerance in large animal models. 26–29 Because of the amount of T-cell expansion seen in acute infections with herpes viruses and to their frequent persistence in the host, herpes viruses can be very potent inducers of heterologous immunity in humans.30,31 Alloreactive CD8+ CTLs that were virus-specific on the autologous MHC have been discovered for both EBV and HSV-2 infections. 14–16 Here we report CD4+ T-cell clones isolated from DQ0602-positive donors that are specific to DQ0602 presenting HSV-2 VP16 40–50 peptide and that are alloreactive to DQ0601. This cross-reactivity might play a role in rejection reactions of HSV-2-positive organ recipients that have the DR15/DQ0602 haplotype and received an organ from a DR15 matched DQ0601 positive donor.

To estimate whether VP16 40–50 specific, DQ0602 restricted T-cell clones are commonly DQ0601 alloreactive, we used two different cloning strategies, the first of which would selectively clone VP16 40–50 specific clones and the second would enrich DQ0601 alloreactive T cells prior to selective cloning of DQ0602/VP16 40–50 reactive clones out of this pool of DQ0601 alloreactive T cells. By means of these strategies, we isolated T-cell clones from two different DQ0602 positive HSV-2-infected individuals. DQ0601 alloreactive T cells that cross-react with DQ0602/VP16 40–50 at high avidity as evaluated by tetramer staining32 occurred at very low frequency. However, moderately cross-reactive clones were detectable in both patients. The alloreactive, cross-reacting clones were mostly negative for staining with the DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer, even though the clones did recognize DQ0602 presenting VP16 40–50 as shown by specific proliferation. Lacking a DQ0601 tetramer, we concluded from the amount of proliferative response with DQ0601 that most of the clones did also recognize DQ0601 only with moderate affinity. In some case lower affinity T cells have been shown resist anergy induction by ciclosporin A, and other immunomodulating agents, so that these T cells might pose a problem in transplant patients despite their low affinity.33 Most of the clones that were derived from DQ0601 allo-stimulated bulk cultures were negative for staining with the DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer. This is a surprising result as the DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer was used to single cell sort the bulk culture to isolate these clones. This finding can be explained by the low frequency of tetramer positive T cells in the bulk culture as seen in Fig. 2(b). Many of the clones obtained by single-sorting the ‘tetramer-positive’ cells in an DQ0601 allostimulated bulk culture probably represent background staining with the tetramer.

From one of our patients we were able to isolate two high affinity DQ0602/VP16 40–50 tetramer positive, strongly DQ0601 alloreactive T-cell clones, 44 and 11f6. We demonstrated that these clones were not sister clones by DNA sequencing of the junction of the variable region of the TCR-β chain. DQ0601 and DQ0602 are very similar MHC class II molecules. However, the DQ0602 and DQ0601 molecules do not only differ in the β-chain but also use slightly different α-chains.34 The DQA1*0102 allele, that encodes the α-chain of DQ0602 is also used in the DQ0604 molecule. Similarly, the DQA1*0103 α-chain of DQ0601 is also present in DQ0603. Interestingly, DQ0603 and DQ0604 cannot stimulate clone 44 even in the presence of its cognate peptide VP16 40–50 (Fig. 1).

Further examination of clones 44 and 11f6 revealed that both clones produce large amounts of Granzyme B and Th2-like cytokines. With this pattern of effector mechanisms two scenarios of their action in a DQ0601/DQ0601 mismatched organ donor/recipient setting are conceivable: the T-cell clones might injure the graft directly via cell-mediated cytotoxicity, or they might be providing T-cell help to graft-reactive B cells, which might contribute to chronic rejection.35 Very little IL-10 was detected which is inconsistent with the idea that these pre-existing alloreactive T cell might have beneficial TR1-like properties in a transplant setting.

Taken together our data demonstrates that there areDQ0601 alloreactive T cells that cross-react with VP16 40–50 and DQ0602 as restriction element. The cross-reactivity appears to be weak, as most of the clones we isolated are not cross-reactive, and most of the cross-reactive clones are only weakly reactive to one of the two stimuli. However, we were able to isolate two independent T-cell clones that show a strong reaction with both DQ0602 presented VP16 40–50 peptide and DQ0601. Similar T-cell clones, that might pre-exist in a DQ0602-positive, HSV-2-infected organ recipient could possibly become reactivated by a DQ0601 positive donor organ. Considering that fact that DQ0601 and DQ0602 both can be found linked to DR15, even DR matched donor-recipient pairs could be affected by this alloreactivity. The DR15/DQ0601 haplotype is quite rare, but comparable cross-reactivity between similar HLA molecules might very well exist.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the grant number AI-44443 from the NIH and by the JDRF grant: JDRF Center for Translational Research at the Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason.

Abbreviations

- B-LCL

B lymphoblastoid cell line

- BLS

bare lymphocyte syndrome

- DQ0602

HLA class two dimer formed by the HLA DQA1*0102 α -chain and the DQB1*0602 β-chain

- HSV-2

herpes simplex virus type 2

References

- 1.Opelz G, Wujciak T, Dohler B, Scherer S, Mytilineos J. HLA compatibility and organ transplant survival. Collaborative Transplant Study Rev Immunogenet. 1999;1:334–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sayegh MH, Watschinger B, Carpenter CB. Mechanisms of T cell recognition of alloantigen. The role of peptides. Transplantation. 1994;57:1295–302. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199405150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawelec G, Adibzadeh M, Bornhak S, et al. The role of endogenous peptides in the direct pathway of alloreactivity to human MHC class II molecules expressed on CHO cells. Immunol Rev. 1996;154:155–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinle A, Reinhardt C, Jantzer P, Schendel DJ. In vivo expansion of HLA-B35 alloreactive T cells sharing homologous T cell receptors: evidence for maintenance of an oligoclonally dominated allospecificity by persistent stimulation with an autologous MHC/peptide complex. J Exp Med. 1995;181:503–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obst R, Netuschil N, Klopfer K, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG. The role of peptides in T cell alloreactivity is determined by self-major histocompatibility complex molecules. J Exp Med. 2000;191:805–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huseby ES, Crawford F, White J, Kappler J, Marrack P. Negative selection imparts peptide specificity to the mature T cell repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11565–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford F, Huseby E, White J, Marrack P, Kappler JW. Mimotopes for alloreactive and conventional T cells in a peptide-MHC display library. Plos Biol. 2004;2:E90. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brock R, Wiesmuller KH, Jung G, Walden P. Molecular basis for the recognition of two structurally different major histocompatibility complex/peptide complexes by a single T-cell receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:13108–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Udaka K, Wiesmuller KH, Kienle S, Jung G, Walden P. Self-MHC-restricted peptides recognized by an alloreactive T lymphocyte clone. J Immunol. 1996;157:670–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moris A, Teichgraber V, Gauthier L, Buhring HJ, Rammensee HG. Cutting edge: characterization of allorestricted and peptide-selective alloreactive T cells using HLA-tetramer selection. J Immunol. 2001;166:4818–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.4818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheil JM, Bevan MJ, Lefrancois L. Characterization of dual-reactive H-2Kb-restricted anti-vesicular stomatitus virus and alloreactive cytotoxic T cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:3654–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang H, Welsh RM. Induction of alloreactive cytotoxic T cells by acute virus infection of mice. J Immunol. 1986;136:1186–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braciale TJ, Andrew ME, Braciale VL. Simultaneous expression of H-2-restricted and alloreactive recognition by a cloned line of influenza virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1981;153:1371–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.5.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burrows SR, Silins SL, Khanna R, Burrows JM, Rischmueller M, McCluskey J, Moss DJ. Cross-reactive memory T cells for Epstein–Barr virus augment the alloresponse to common human leukocyte antigens: degenerate recognition of major histocompatibility complex-bound peptide by T cells and its role in alloreactivity. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1726–36. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burrows SR, Silins SL, Cross SM, Peh CA, Rischmueller M, Burrows JM, Elliott SL, McCluskey J. Human leukocyte antigen phenotype imposes complex constraints on the antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte repertoire. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:178–82. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koelle DM, Chen HB, McClurkan CM, Petersdorf EW. Herpes simplex virus type 2-specific CD8 cytotoxic T lymphocyte cross-reactivity against prevalent HLA class I alleles. Blood. 2002;99:3844–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruya E, Takemoto S, Terasaki PI. HLA matching: identification of permissible HLA mismatches. In: Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, editors. Clinical Transplants. Los Angeles: UCLA Tissue Typing Laboratory; 1993. pp. 511–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennecke J, Wiley DC. Structure of a complex of the human alpha/beta T cell receptor (TCR) HA1.7, influenza hemagglutinin peptide, and major histocompatibility complex class II molecule, HLA-DR4 (DRA*0101 and DRB1*0401): insight into TCR cross-restriction and alloreactivity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:571–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ettinger RA, Liu AW, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. Beta 57-Asp plays an essential role in the unique SDS stability of HLA-DQA1*0102/DQB1*0602 alpha beta protein dimer, the class II MHC allele associated with protection from insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Immunol. 2000;165:3232–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupont B, editor. Immmunobiology of HLA Histocompatibility testing. New York: Springer Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwok WW, Liu AW, Novak EJ, Gebe JA, Ettinger RA, Nepom GT, Reymond SN, Koelle DM. 2000 HLA-DQ tetramers indentify epitope-specific T cells in peripheral blood of herpes simplex virus type 2-infected individuals: direct detection of immunodominant antigen-responsive cells. J Immunol. 1987;164:4244–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genevee C, Diu A, Nierat J, et al. An experimentally validated panel of subfamily-specific oligonucleotide primers (V alpha 1-w29/V beta 1-w24) for the study of human T cell receptor variable V gene segment usage by polymerase chain reaction. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1261–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrows SR, Khanna R, Silins SL, Moss DJ. The influence of antiviral T-cell responses on the alloreactive repertoire. Immunol Today. 1999;20:203–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh RM, Selin LK. No one is naive. the significance of heterologous T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:417–26. doi: 10.1038/nri820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams AB, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Heterologous immunity: an overlooked barrier to tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:147–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Daniels KA, Brehm MA, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J Virol. 2000;74:2210–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2210-2218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams MA, Onami TM, Adams AB, Durham MM, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Larsen CP. Cutting edge: persistent viral infection prevents tolerance induction and escapes immune control following CD28/CD40 blockade-based regimen. J Immunol. 2002;169:5387–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams MA, Tan JT, Adams AB, et al. Characterization of virus-mediated inhibition of mixed chimerism and allospecific tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167:4987–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, et al. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1887–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin X, Demoitie MA, Donahoe SM, et al. High frequency of cytomegalovirus-specific cytotoxic T-effector cells in HLA-A*0201-positive subjects during multiple viral coinfections. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:165–75. doi: 10.1086/315201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callan MF, Steven N, Krausa P, et al. Large clonal expansions of CD8+ T cells in acute infectious mononucleosis. Nat Med. 1996;2:906–11. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reichstetter S, Ettinger RA, Liu AW, Gebe JA, Nepom GT, Kwok WW. Distinct T cell interactions with HLA class II tetramers characterize a spectrum of TCR affinities in the human antigen-specific T cell response. J Immunol. 2000;165:6994–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prud'homme GJ, Parfrey NA, Vanier LE. Cyclosporine-induced autoimmunity and immune hyperreactivity. Autoimmunity. 1991;9:345–56. doi: 10.3109/08916939108997137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh SG. HLA class II region sequences 1998. Tissue Antigens. 1998;51:467–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1998.tb02984.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rifle G, Mousson C, Martin L, Guignier F, Hajji K. Donor-specific antibodies in allograft rejection: clinical and experimental data. Transplantation. 2005;79:S14–S18. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153292.49621.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]