Abstract

Different genetic mutations have been described in complement components resulting in total or subtotal deficiency states. In this work we report the genetic basis of C7 deficiency in a previously reported Spanish patient exhibiting a combined total deficiency of C7 and C4B associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Exon-specific polymerase chain reaction and sequencing revealed a not previously described single base mutation in exon 10 (T1458A) leading to a stop codon that causes the premature truncation of the C7 protein (C464X). Additionally, a C to A transversion at position 1561 (exon 11) was found in the patient resulting in an amino acid change (R499S). This latter mutation has been previously reported in individuals with subtotal C7 deficiency or with combined subtotal C6/C7 deficiency from widely spaced geographical areas. Another novel mutation was found in a second patient with meningococcal meningitis of Bolivian and Czech origin; a 11-base pair deletion of nucleotides 631–641 in exon 6 leading to the generation of a downstream stop codon causing the premature truncation of the C7 protein product (T189 × 193). This patient was found to be a heterozygous compound for another mutation in C7; a two-base pair deletion of nucleotides 1922 and 1923, 1923 and 1924 or 1924 and 1925 in exon 14 (1922delAG/1923delGA/1924delAG), leading again to the generation of a downstream stop codon that provokes the truncation of the C7 protein (S620×630). This latter mutation has been recently reported by our group in another Spanish family. Our results provide more evidences for the heterogeneous molecular basis of C7 deficiency.

Keywords: C7 deficiency, C7 gene mutations, meningococcal meningitis, systemic lupus erythematosus

Introduction

Inherited deficiencies of the early acting classic pathway complement components predispose to autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), whereas genetically determined human deficiencies of any of the terminal complement components are usually associated with an increased risk to recurrent pyogenic infections, mainly neisserial.1 However, individuals with early acting complement deficiencies may develop pyogenic infections2 and those with late-acting complement deficiencies may have autoimmune manifestations.3 Moreover, individuals with any complement deficiency may be completely healthy,4–6 indicating that other genetic or environmental factors may be relevant for the heterogeneous clinical manifestations of complement deficiencies.

C7 is one of the five terminal complement proteins that upon activation of either the classic, alternative or lectin pathway interacts sequentially to form a large protein-protein complex, called membrane attack complex (MAC). Assembly of the MAC on target cells results in cell killing,7 although the precise mechanism of complement-mediated cytotoxicity remains unresolved. There are two hypotheses: in one model, the polar domains of inserted complement proteins cause local distortion of the phospholipid bilayer, resulting in ‘leaky patches’;8 the alternative, ‘pore’, model proposes that the polar surfaces of the individual complement components come together to form a hydrophilic channel through the membrane.9 The single polypeptide chain of C7 is composed of 821 amino acid residues and is structurally similar to the other MAC components C6, C8α, C8β, and C9.10,11 The gene for C7 has been shown to span about 80 kb of DNA, is encoded by 18 exons11 and is located on chromosome 5p13, which also encode C6 and C9.12 Typically, terminal complement-deficient subjects present in adolescence or in young adulthood, and suffer from recurrent meningococcal infections with especially the rarer serogroups.13

The investigation reported here focused on the study of the genetic basis of C7 deficiency in two unrelated patients. Patient 1 was previously reported to have combined total deficiency of C7 and C4B associated with SLE.14 Terminal complement component deficiency was suspected in patient 2 because of two episodes of neisserial meningitis with septic shock, lack of total serum haemolytic activity (CH50), as well as by the finding of low levels of C7 by radial immunodiffusion (RID). The determination of C7 DNA sequence allowed us to detect two novel mutations in these patients.

Subjects and methods

Patient 1

The C7 deficient case, a Spanish 32-year-old woman (now 45 years old), was discovered because of a history of proliferative mesangial glomerulonephritis in childhood. Details of her past medical history as well as immunochemical, functional and molecular studies of patient's complement components were reported previously.14 Briefly, functional C7 assays showed a phenotypically homozygous C7 deficiency in the patient, whereas C4 molecular analyses demonstrated that only C4A proteins could be expressed, resulting in a combined complete C7 and C4B deficiency. She lacked any C7 detectable protein by using rocket electrophoresis and immunobloting with anti-C7 serum. No C7 haemolytic activity was observed, although their total haemolytic activity (CH50) could be restored to 100% by the addition of functional C7 protein.14 Subsequent analysis by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) revealed very low levels of C7 in the serum of the patient (0·094 mg/ml). No history of repeated infectious nor meningococcal disease episodes have been recorded to date.

Patient 2

This case is a Swiss 23-year-old woman of Bolivian and Czech origin with a clinical history of two episodes of meningococcal meningitis with septic shock (at age 17 and 22). Complement analyses revealed undetectable CH50 activity as well as low levels of C7 in patient's serum, whereas levels of C5, C6 and C8 were within the normal range (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Terminal complement component concentrations measured by RID in serum from patient 2

| Component | Concentration (mg/l) | Normal range* (mg/l) |

|---|---|---|

| C5 | 139 | 115–150 |

| C6 | 117 | 45–96 |

| C7 | 13 | 55–85 |

| C8 | 162 | 112–172 |

| C9 | ND | 125–265 |

Institut für Klinische Chemie und Hämatologie, Kantonsspital, St Gallen, Switzerland

ND, not determined.

For this investigation, informed consent was obtained from the patients under study according to the guidelines of the Hospital Virgen del Rocío Bioethic Committee (patient 1), and the Swiss Society of Medical Genetics (patient 2).

C7 gene mutational analysis

Genomic DNA isolation and exon-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the C7 gene were performed as described.6,15,16 For each sample three separated reactions were carried out. Briefly, exon-specific amplified PCR products were purified and reamplified. Sequencing was carried out in a CEQ 8000 Genetic Analysis System (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. For each sample three independent reactions were carried out.6,17 Computer analysis of DNA sequences was performed using the CEQ 8000 Sequence Analysis Software Package.

Results and discussion

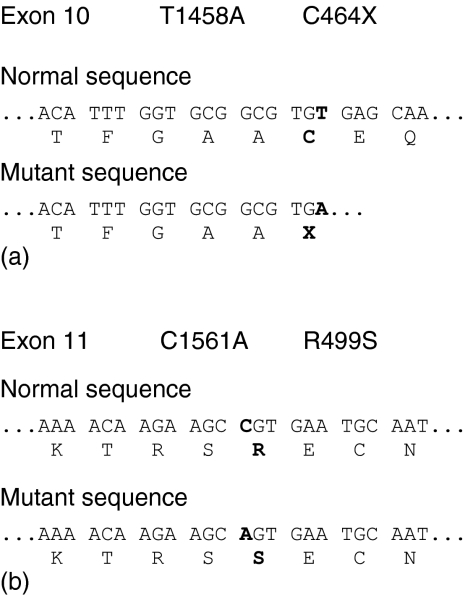

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood drawn from the patients. Sequence analysis of exons 1–17 of the C7 gene of patient 1 revealed a novel point mutation at cDNA nucleotide 1458 (exon 10); there was an A instead of a T (Fig. 1a). This transversion generates a termination codon leading to the premature truncation of the encoded C7 protein (C464X) in the perforin domain of the C7 protein. If translated, the mutant C7 would lack the carboxy-terminal 357 aminoacid residues, which represent approximately 43·5% of the molecular size of the polypeptide. As this truncated part contains domains that are important for C7 functionality10,11,18 the truncated C7 is probably not able to participate in the formation of MAC even if secreted.

Figure 1.

Definition of the mutations found in exons 10 (a) and 11 (b) in patient 1. The normal and defective DNA sequences as well as the deduced amino acid sequences are given.

Additionally, a C to A transversion at cDNA position 1561 of exon 11 (Fig. 1b) was found in this patient and causes the substitution of an Arg by a Ser (R499S) in the central thrombospondin repeat unit. This residue is highly conserved at the equivalent location in all terminal components of complement, and it is at a similar location in the thrombospondin domains of other proteins suggesting that this residue could be functionally important.19,20 This mutation has been previously reported in one Russian patient with subtotal C7 deficiency19 as well as in seven cases of combined subtotal C6/C7 deficiency from UK (four patients), Western Cape, South Africa (one patient), Russia (one patient) and Germany (one patient).19 This replacement is responsible for protein charge difference, but has not been confirmed so far to be responsible for C7 deficiency, although this is strongly supported by patient data.13,19

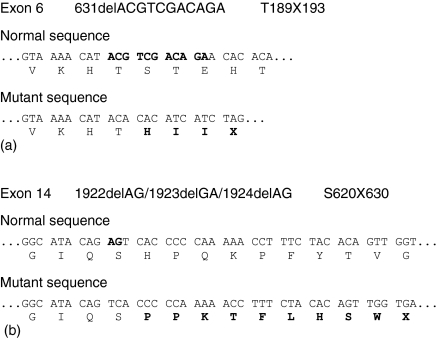

Direct sequencing of the C7 gene in patient 2 disclosed a novel mutation in exon 6 (Fig. 2a); a 11-base pair deletion of nucleotides 631–641 leading to the generation of a downstream stop codon causing the premature truncation of the protein product (T189×193) in the perforin domain of C7. If translated, the mutant protein would lack the carboxy-terminal 628 amino acid residues, which represent approximately 76·2% of the molecular size of the polypeptide. As this truncated part contains domains that are important for C7 functionality10,11,18 this heavily truncated C7 (its molecular size is only 23·8% of normal C7) is very likely not able to participate in the formation of MAC even if secreted. In this way, it has been reported that deletions in exons 6 and 7, as well as other mutations located downstream,5,6,18 lead to a complete loss of complement lytic function.

Figure 2.

Sequence of part of exons 6 (a) and 14 (b) in patient 2. The normal and defective DNA sequences as well as the deduced amino acid sequences are given.

Patient 2 was a heterozygous compound for another defect in the C7 gene which has been recently reported by our group in another Spanish family15. A two base-pair deletion located in nucleotides 1922 and 1923, 1923 and 1924 or 1924 and 1925 (1922delAG/1923delGA/1924delAG) in exon 14 (Fig. 2b) leading again to the generation of a downstream stop codon causing the truncation of the C7 protein product (S620×630) in the complement control protein domain of the molecule. If translated, the mutant protein would lack the carboxy-terminal 199 aminoacid residues leading to a protein product representing around the 77% of the molecular size of the whole C7 polypeptide chain.

Low levels of non-haemolytically active C7 were detected in both patients, indicating that there was a subtotal C7 deficiency. Unfortunately, we could not examine polymorphonuclear cells from the patients for the presence of mRNA for the dysfunctional C7.

To date, 19 different molecular defects leading to total or subtotal C7 deficiency defects have been reported.17,21,22 Here we report two novel mutations in the C7 gene in two unrelated individuals with C7 deficiency leading to undetectable CH50 activity. In conclusion, our results provide more evidence that the molecular bases for complement component C7 deficiency are heterogeneous, because different individuals carry distinct molecular defects, although some defects appear to be prevalent in individuals from certain populations or living in defined geographical areas.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the collaboration of the patients under study. We thank Dr Sheila Unger for expert clinical guidance of Dr Rieubland, Carmen Guzmán and José Manuel Lara for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported partially by grants from Consejería de Salud, Junta de Andalucía (28/02 and 0169/2005), and Plan Andaluz de Investigación (PAI, grupo CTS-0197). S Barroso is supported by grant REIPI C013 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Abbreviations

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RID

radial immunodiffusion

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

References

- 1.Ross SC, Densen P. Complement deficiency states and infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and consequences of neisserial and other infections in an immune deficiency. Medicine. 1984;61:243–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rowe PC, McLean RH, Wood RH, Leggiadaro RJ, Winklestein JA. Association of homozygous C4B deficiency with bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:448–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.3.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitz HJ, Miller GW, Lint TF, Ali MA, Gewurz H. Deficiency of C7 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Solubilization of immune complexes in complement-deficient sera. Arthritis Rheum. 1981;24:87–93. doi: 10.1002/art.1780240114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauptmann G. Frequency of complement deficiencies in man, disease associations and chromosome assignment of complement genes and linkage groups. Complement Inflamm. 1989;6:74–80. doi: 10.1159/000463077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernie BA, Orren A, Sheehan G, Schlesinger M, Hobart MJ. Molecular basis of C7 deficiency. Three different defects. J Immunol. 1997;159:1019–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vázquez-Bermúdez MF, Barroso S, Walter K, et al. Complement component C7 deficiency in a Spanish family. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:240–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller-Eberhard HJ. The membrane attack complex of complement. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:503–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.002443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esser AF. Big MAC attack: complement proteins cause leaky patches. Immunol Today. 1991;12:316–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90006-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhakdi S, Tranum-Jensen J. Complement lysis: a hole is a hole. Immunol Today. 1991;12:318–20. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90007-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiScipio RG, Chakravarti DN, Muller-Eberhard HJ, Fey GH. The structure of human complement component C7 and the C5b-7 complex. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:549–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobart MJ, Fernie BA, DiScipio RG. Structure of the human C7 gene and comparison with the C6, C8A, C8B, and C9 genes. J Immunol. 1995;154:5188–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbott C, West L, Povey S, Jeremiah S, Murad Z, DiScipio RG, Fey G. The gene for the human complement component C9 mapped to chromosome 5 by polymerase chain reaction. Genomics. 1989;4:605–9. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(89)90286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Würzner R, Witzel-Schlömp Tokunaga K, Fernie BA, Hobart MJ, Orren A. Reference typing report for complement components C6, C7 and C9 including mutations leading to deficiencies. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1998;15:268–85. doi: 10.1159/000019082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segurado OG, Arnáiz-Villena A, Iglesias-Casarrubios P, Martínez-Laso J, Vicario JL, Fontán G, López-Trasacasa M. Combined total deficiency of C7 and C4B with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;87:410–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasaki E. Sample preparation from blood, cells and other fluids. In: Innis M, Gelfand D, Sinisky J, White T, editors. PCR Protocols A Guide to Methods and Applications. San Diego: Academic Press; 1990. pp. 146–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishizaka H, Horiuchi T, Zhu ZB, Fukumori Y, Volanakis JE. Genetic bases of human complement C7 deficiency. J Immunol. 1996;157:4239–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barroso S, Sánchez B, Álvarez AJ, López-Trascasa M, Lanuza A, Luque R, Wichmann I, Núñez-Roldán A. Complement component C7 deficiency in two Spanish families. Immunology. 2004;113:518–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobart M. In: The Complement Facts Book. Morley BJ, Walport MJ, editors. London: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 117–22. C7. In. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernie BA, Würzner R, Orren A, et al. Molecular bases of combined and subtotal deficiencies of C6 and C7 and their effects in combination with other C6 and C7 deficiencies. J Immunol. 1996;157:3648–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Würzner R, Mewar D, Fernie BA, Hobart MJ, Lachman PJ. Importance of the third thrombospondin repeat of C6 for terminal complement complex assembly. Immunology. 1995;85:214–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Würzner R. Deficiencies of the complement MAC II gene cluster (C6, C7, C9): is subtotal C6 deficiency of particular evolutionary benefit? Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:156–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ki CS, Kim JW, Kim HJ, Choi SM, Ha GY, Kang HJ, Kim WD. Two novel mutations in the C7 gene in a Korean patient with complement C7 deficiency. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:220–4. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]