Abstract

The neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, plays a central role in immunoglobulin G (IgG) transport across placental barriers. Genetic variations of FcRn-dependent transport across the placenta may influence antibody-mediated pathologies of the fetus and the newborn. Sequencing analysis of 20 unrelated individuals demonstrated no missense mutation within the five exons of the FcRn gene. However, a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) region within the FcRn promoter was observed, consisting of five different alleles (VNTR1–VNTR5). Alleles with two (VNTR2) and three (VNTR3) repeats were found to be most common in Caucasians (7·5 and 92·0%, respectively). Real-time polymerase chain reaction revealed that monocytes from VNTR3 homozygous individuals express 1·66-fold more FcRn transcript than do monocytes from VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygous individuals (P = 0·002). In reporter plasmid assays, the VNTR3 allele supported the transcription of a reporter gene twice as effectively as did the VNTR2 allele (P = 0·003). Finally, under acidic conditions, monocytes from VNTR3 homozygous individuals showed an increased binding to polyvalent human IgG when compared with monocytes from VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygous individuals (P = 0·021). These data indicate that a VNTR promoter polymorphism influences the expression of the FcRn receptor, leading to different IgG-binding capacities.

Keywords: IgG, neonatal Fc receptor, promoter polymorphism

Introduction

The neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, has been found at the maternal–fetal barrier in humans1,2 and in a number of adult tissues, including endothelium,3 hepatocytes,4 epithelial cells,5–7 monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells.8 Evidence has emerged that FcRn plays an important role in immunoglobulin G (IgG) homeostasis and in perinatal IgG transport,3,9 whereas its function both inside white blood cells (WBC) and on WBC surfaces remains elusive at present.

In endothelial cells, IgG bound to FcRn is rescued from degradation and can be transported back to the cell surface, where it may re-enter the circulation.10,11 At the maternal–fetal barrier, FcRn can efficiently transport IgG across trophoblast-derived BeWo cells and human placental-derived endothelial cells.9,12,13 In addition, FcRn dependency of IgG transport across the human placenta has been demonstrated elegantly in an ex vivo placenta model.14

The latter finding is of special interest for the understanding of fetal/neonatal alloimmune haemocytopenias, in which the mother produces antibodies against paternal blood groups on fetal cells. Rhesus D and PlA1 (HPA-1a) antigens are the most commonly known polymorphisms on red cells and platelets, respectively, that lead to antibody production and subsequent haemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) or fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT). Previous studies have failed to demonstrate a direct association between the amount of red cell alloantibodies in maternal serum and the severity of HDN.15,16 The same seems to be true for platelet alloantibodies, as a large prospective study found no correlation between the titre of anti-HPA-1a and severity of FNAIT,17 although contrasting data have been published.18,19

One striking explanation for this noncorrelation between maternal alloantibody titre and severity of fetal/neonatal disease would be a differentially effective transport of IgG alloantibodies across the maternal–fetal barrier. As FcRn plays a central role in shuffling IgG across the placenta, we sought to screen the FcRn gene for polymorphisms. Here, we describe a variability of FcRn associated with variable number of tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphisms in the promoter region of the FcRn gene.

Materials and methods

DNA samples

DNA was isolated from 447 unselected healthy blood donors and stored at −30°. All individuals gave informed consent to participate in the study, according to the guidelines of the University Hospital's Committee on Ethics.

DNA sequence analysis

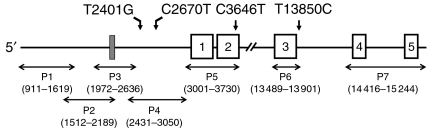

To analyse the coding and promoter regions of the FcRn gene, DNA from 20 individuals was amplified using the sequencing strategy shown in Fig. 1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were sequenced using PCR forward primers and analysed on an ABI-Prism 3100 (Applied Biosystems, Weiterstadt, Germany).

Figure 1.

Sequencing strategy for analysis of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) gene. Silent mutations are indicated with according base numbers, and the variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) region is indicated by a grey box. Primer sequences are given in Table 1.

PCR for VNTR polymorphism of the FcRn gene

Four-hundred and twenty-seven unrelated healthy blood donors were assessed. Aliquots of 60 ng of DNA were amplified using 0·5 pmol of allele-specific sense primer and antisense primer (which encompass the VNTR site of FcRn), 0·2 mmol desoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP) and 2·0 U of TaqGold polymerase, on a PCR Express Thermal Cycler (ThermoLife Sciences, Ulm, Germany) in a total volume of 50 µl. After heating at 95° for 10 min, PCR was performed under the following conditions: denaturation (30 seconds, 95°), annealing (40 seconds, 64°) and extension (30 seconds, 72°) for 32 cycles, followed by a final extension (5 min, 72°). PCR products were analysed on 1·6% agarose gels using Tris-borate EDTA (TBE) buffer (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Quantification of FcRn-specific transcripts by real-time PCR

Mononuclear cells were isolated from EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood by Ficoll gradient centrifugation. After incubation with anti-CD14-coated immunomagnetic beads, bound cells were positively selected by passing the suspensions through a paramagnetic column (autoMACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was isolated from 5 × 106 cells using the Qiagen RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and transcribed into cDNA using Ready-To-Go™ You-Prime First-Strand Beads (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany). Real-time PCR was performed on an ABI Prism 7000 PCR cycler (Applied Biosystems). The following validated PCR primers and TaqMan MGB probes (FAM labelled) were used: FCGRT (Assay ID: Hs00175415_m1) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Assay ID: Hs99999905_m1) (both from Applied Biosystems). Conditions were as follows: 1 × 2 min at 50°, 1 × 10 min at 95° hot start, 40–50 cycles of denaturation (15 seconds, 95°) and combined annealing/extension (1 min, 60°). Relative changes in gene expression of the FcRn transcript were calculated using the 2(-delta delta C(T)) (δδCT) method, as described previously.20

FcRn promoter-luciferase reporter assays

Promoter DNA was amplified using PCR with genomic DNA and appropriate primers. Reporter constructs were generated by cloning the amplified segments into a renilla luciferase reporter plasmid (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). Constructs were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Myelomonocytic U937 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Wesel, Germany) were cultured in RPMI containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and penicillin/streptomycin supplement, and then resuspended in OptiMEM (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) prior to transfection. Aliquots of 4–8 × 105 cells were transfected in six-well plates with 1 µg of reporter construct and 1 µg of firefly luciferase control vector (Invitrogen) in the presence of 3 µg of lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Cell culture medium was added after 6 hr. After 48 hr of incubation, cell culture supernatant was collected and directly analysed on a luminometer (Berthold, Wildbach, Germany) for renilla and firefly luciferase activity according to the manufacturer's protocol. Renilla activity was normalized to firefly control activity in each experiment. All experiments were repeated twice under identical conditions.

Monocyte binding to immobilized IgG

Ninety-six-well plates were coated with either human polyvalent IgG (Octapharma, Langenfeld, Germany) at a concentration of 3 µg/well or in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS) for 2 hr at 37° and washed twice before use. Mononuclear cells of VNTR3/VNTR3 homozygous (n = 4) and VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygous (n = 4) individuals were isolated by autoMACS (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine at a final concentration of 8 × 106/ml, and the pH was adjusted to 7·2, 6·5, or 6·0. A total of 8 × 105 cells was added to each well and allowed to bind to IgG at 37°, 5% CO2, for 1 hr. Plates were then washed twice with D-PBS at the appropriate pH. Bound cells were fixed with 150 µl of methanol/acetone (1 : 1, v/v) for 15 min and stained with 50 µl of staining solution containing 0·5% crystal violet, 20% methanol and 79·5% distilled water. Finally, 100 µl of methanol/acetic acid/distilled water (4 : 1 : 5, v/v/v) was added to each well, and the optical density was measured photometrically (BIO-TEK, Neu-Fahrn, Germany) at 592 nm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by Mann–Whitney U-test. A P-value of < 0·05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

The entire coding region of the FcRn gene was sequenced directly according to the strategy depicted in Fig. 1. The results of 20 nonrelated individuals were compared with the DNA sequences from the public database. We detected a heterozygous silent mutation (C3646T) in exon 2 in two individuals, but no other mutations were found within the entire coding region. Both individuals bearing the C3646T mutation carried additional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at intronic positions T2401G, C2670T and T13850C in a heterozygous state. Subsequent DNA analysis of the 5′ untranslated region in both individuals revealed a VNTR region of a 37-bp-long motif in heterozygous form (Fig. 1, grey box), with three repeats (VNTR3) on one allele and two repeats (VNTR2) on the other allele.

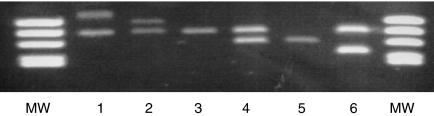

These findings prompted us to analyse a larger cohort of individuals by using PCR with primers encompassing the VNTR region. Genotyping of 427 unrelated subjects revealed five PCR products that differed in size (Fig. 2), consistent with one to five repeats of a 37-bp-long motif. This result was verified subsequently by DNA sequencing (GenBank accession numbers: AF453513–AF453517). The calculated gene frequencies for the five VNTR alleles were 0·1, 7·5, 92·0, 0·2 and 0·2%, in order of increasing numbers of repeats (VNTR1, VNTR2, VNTR3, VNTR4 and VNTR5, respectively). Therefore, VNTR3 is the most common genotype in Caucasians, whereas VNTR2 is less common. All other variants are rare. The presence of the silent mutation (C3646T) in exon 2 was investigated in 16 VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygotes and 16 VNTR3 homozygotes by DNA sequencing. Whereas all VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygotes carried the silent mutation in a heterozygous state, VNTR3 homozygous individuals were homozygous for C at this position.

Figure 2.

Results of the variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A PCR with allele-specific sense and antisense primers encompassing the VNTR region 5′ of the FCRN gene was performed. Results from individuals with different VNTR combinations are as follows: lane 1, VNTR5/VNTR3; lane 2, VNTR4/VNTR3; lane 3, VNTR3/VNTR3; lane 4, VNTR3/VNTR2; lane 5, VNTR2/VNTR2; and lane 6, VNTR3/VNTR1. MW, molecular weight.

In order to study the phenotypic relevance of the VNTR promoter polymorphism, we compared the amount of FcRn transcript between carriers of VNTR2 and VNTR3 alleles. Total RNA was isolated from monocytes of genotyped individuals and subsequently quantified by real-time PCR using FcRn-specific primers. Five donors of each genotype were analysed (Table 2). Calculation of relative mRNA expression revealed a mean 2−δCT value20 of 0·073 ± 0·01 in homozygotes and a mean 2−δCT value of 0·045 ± 0·011 in heterozygotes, a difference that was found to be statistically significant (P = 0·002). We then applied the δδCT method to compare the relative increase of FcRn transcript in homozygotes and heterozygotes.20 The increase of FcRn transcript in VNTR3/VNTR3 homozygous individuals was 1·66-fold (95% confidence interval: 1·28–2·04-fold) when compared with VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygotes. These results indicate that the VNTR3 allelic form is able to transcribe the FcRn gene more efficiently than the VNTR2 allele.

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of Fc-receptor neonatal (FcRn) transcripts in monocytes

| Donor | VNTR genotype | δCT | 2−δCT | Mean 2−δCT ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3/3 | 3·73 | 0·0754 | 0·073 ± 0·01 | |

| 2 | 3/3 | 3·57 | 0·0842 | ||

| 3 | 3/3 | 3·64 | 0·0802 | ||

| 4 | 3/3 | 3·93 | 0·0656 | ||

| 5 | 3/3 | 4·02 | 0·0616 | P = 0·002 | |

| 6 | 2/3 | 4·49 | 0·0445 | 0·045 ± 0·011 | |

| 7 | 2/3 | 4·34 | 0·0494 | ||

| 8 | 2/3 | 4·36 | 0·0487 | ||

| 9 | 2/3 | 4·16 | 0·0559 | ||

| 10 | 2/3 | 5·18 | 0·0276 |

SD, standard deviation; VNTR, variable number of tandem repeats.

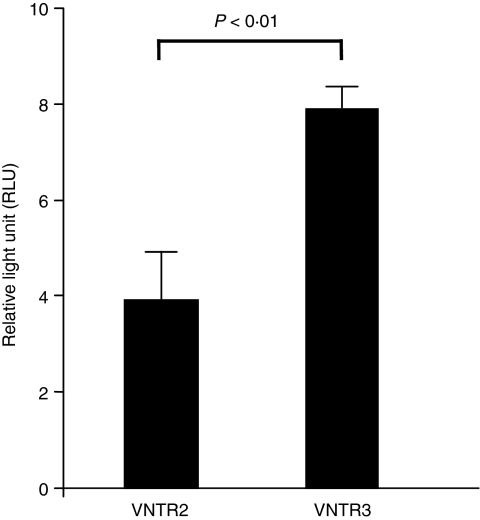

These results were confirmed subsequently by employing a reporter plasmid assay. The putative FcRn promoter region was amplified from position −764 to position +1375 (relative to the FcRn transcription site). This region has previously been shown to support transcription of a CAT reporter gene.21 Renilla luciferase reporter plasmids containing either the VNTR2 or the VNTR3 allele were transfected separately into myelomonocytic U937 cells. Renilla induction from each allelic construct was assayed in duplicate from three independent transfections. Transfection efficacy was determined by cotransfection of a Firefly luciferase vector. As shown in Fig. 3, the VNTR3 allelic form supported transcription of the reporter gene twice as effectively as did the VNTR2 allele (P = 0·003).

Figure 3.

Transcriptional activities of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) promoter alleles. The two most common variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) promoter alleles, VNTR2 and VNTR3, were tested for their ability to support the transcription of a renilla luciferase reporter gene in U937 cells. Renilla values were normalized with the read-out from cotransfected firefly luciferase control plasmid. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

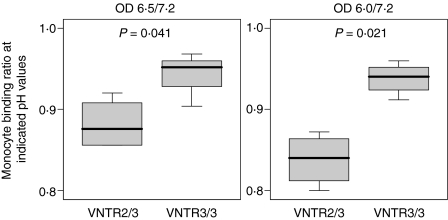

If this different FcRn transcription efficacy is reflected by a variant FcRn expression on cellular surfaces, it is to be expected that the VNTR polymorphism will have an impact on the FcRn-dependent IgG-binding capacity of such cells. Accordingly, we analysed the adhesion of human monocytes derived from VNTR3/VNTR3 homozygous and VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygous donors (n = 4 for each genotype) to immobilized human polyvalent IgG. As it has previously been demonstrated that the affinity of FcRn for IgG is reduced by about two orders of magnitude when the pH is raised from 6·0 to 7·0,22 IgG binding was assessed at pH 6·5 and 6·0, respectively. Monocyte adhesion to IgG at pH 7·2 is predominantly mediated by other IgG receptors and was used as a denominator value for interindividual normalization. We found that monocytes from homozygous individuals displayed an increased binding to IgG at pH 6·5 when compared with monocytes from heterozygous individuals (P = 0·041; Fig. 4). Importantly, this difference became more pronounced at a pH of 6·0 (P = 0·021; Fig. 4), as anticipated for pH-dependent FcRn-specific binding.

Figure 4.

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding capacities of human monocytes. The binding of monocytes to immobilized polyvalent human IgG was analysed under different conditions of pH, as indicated. Experiments were performed with monocytes from four different individuals of each genotype. Results are given in a box plot with the centre line representing the sample median, and lower and upper borders of the box representing the 25th and 75th percentile, respectively. The whiskers indicate minimal and maximal extreme values of the sample.

Discussion

The neonatal Fc receptor is an important receptor in immunoglobulin transport and homeostasis, but only limited information is available regarding its interindividual variability. We speculated that the binding specificity of human FcRn, which is surprisingly stringent, might be changed by genetic alterations, as Zhou and colleagues23 were able to generate human FcRn variants that bind IgG with similar properties as mouse FcRn by employing site-directed mutagenesis. However, we were unable to detect any missense mutations within the coding region of FcRn among 20 Caucasian healthy blood donors. This observation indicates that naturally occurring exonic missense mutations of the FcRn gene occur rarely, at least in Caucasians.

In contrast, we were able to identify a VNTR polymorphism consisting of one to five repeats of a 37-bp-long motif (VNTR1–5) in the promoter region of the FcRn gene. Reporter gene analysis showed that the two most common alleles, VNTR3 (92·0%) and VNTR2 (7·5%), display significantly different abilities to promote reporter gene transcription. The VNTR3 allele transcribes FcRn more efficiently when compared with the VNTR2 allele. In our cohort, the VNTR2 genotype is genetically linked to the silent mutation C3646T located on exon 2. Interestingly, Laegreid et al., by comparing 19 different cattle populations, observed that silent mutations of the FcRn gene were associated with a low level of IgG concentrations in newborn calves.24 One may speculate that these silent mutations are also associated with promoter polymorphisms; however, this possibility has not been assessed by these authors.

Several recent reports documented that VNTR polymorphisms located in the promoter region influence the transcriptional activity, resulting in phenotypes with functional differences.25–27 Although the biological mechanism(s) behind these polymorphisms are poorly understood, a defined length for the regulatory region seems to be important for optimal gene transcription.26

Our genetic observations were corroborated by findings obtained from the analysis of monocytes. Employing a real-time quantification method of FcRn transcripts, we were able to demonstrate that monocytes from VNTR2/3 heterozygous individuals carry significantly less FcRn transcript than VNTR3/3 homozygotes. Thus, cells derived from VNTR2 carriers with lower FcRn transcript levels may express less FcRn on the cellular surface and, consequently, may display diminished binding of IgG. Because specific monoclonal antibodies recognizing FcRn are not available, we chose a functional assay to determine whether the changes observed at the mRNA level and promoter activity translate to differences in IgG binding. Indeed, monocytes derived from VNTR2/VNTR3 heterozygotes displayed a diminished IgG-binding capacity when compared with those derived from VNTR3/VNTR3 homozygotes.

We conclude, from our findings, that a VNTR promoter polymorphism influences the transcriptional activity of the FcRn α-chain. Within the Caucasian population, the two most frequent polymorphisms result in differential expression of FcRn on the cell surface of monocytes. Although it is likely that this promoter polymorphism influences the transcription of FcRn not only in monocytes, but in all cells, this has currently not been proven. In placental tissue, lower numbers of FcRn might lead to a less efficient transfer of IgG from the mother to the fetal circulation. In case of maternal alloimmunization, ‘low’ IgG levels of pathogenic antibodies in the fetus may reduce the risk of disease severity. This hypothesis fits to the clinical observation that mothers with high-titre anti-D, but ineffective IgG, transfer capability gave birth to clinically unaffected children.27,28

Besides its relevance as a placental transporter, FcRn is an important mediator in IgG metabolism.10 Effectiveness of intravenous immunoglobulins as a standard therapy of immune thrombocytopenia has recently been shown to be FcRn dependent.29 Thus, well-designed clinical studies are necessary to address the question of whether differential expression of FcRn influences IgG-dependent pathologies in humans.

Table 1.

Primer sequences

| No. | Position | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Forward primers | ||

| 1F | 911–931 | 5′-GGA ACT CGG ATA GAG GTG ACA-3′ |

| 2F | 1512–1532 | 5′-TGA TTA ACA GCG AGC GCT AGG-3′ |

| 3F | 1972–89 | 5′-TCT CGA CAC TGG GTC TGA-3′ |

| 4F | 2431–2450 | 5′-AGG GCA TTG TTG TCA GTC TG-3′ |

| 5F | 3001–3021 | 5′-GTC CCA CTG CAG TCT AGT TCC-3′ |

| 6F | 13 489–13 509 | 5′-GGA GGC CTC TTT CTG TCC CTA-3′ |

| 7F | 14 416–14 438 | 5′-TTG GTG CTG GAA TCT CCG AGG CT-3′ |

| Reverse primers | ||

| 1R | 1619–1599 | 5′-ACT GGG AAA GGA ACT CGA TGC-3′ |

| 2R | 2189–2169 | 5′-TCT ACC CTT GGA CCC AGG AGT-3′ |

| 3R | 2636–2619 | 5′-AGG AAG GAG AAA GAG CAG-3′ |

| 4R | 3050–3031 | 5′-AAA CAG AGC TGA AGG GAG CA-3′ |

| 5R | 3730–3710 | 5′-AAC TGA GGC AGG TGG GCA TGA-3′ |

| 6R | 13 901–13 881 | 5′-GCA GCA GTG AGA CAA GGC AAC-3′ |

| 7R | 15 244–15 224 | 5′-CAC AGC ATG AAA GGG GCC TGA-3′ |

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Heike Berghöfer is highly acknowledged. The authors also wish to thank Dr M. de Haas (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and Dr J. E. Mikulska (Warsaw, Poland), for helpful discussion. This work contains parts of the doctoral thesis of C.G.B and I.S., and was supported by the German Foundation for Haemotherapeutic Research (Bonn, Germany), of which U.J.H.S. is a fellow.

Abbreviations

- CAT

chloramphenicol acetyl transferase

- dNTP

desoxynucleotide triphosphate

- D-PBS

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline

- FAM

6-carboxyfluorescein

- FCGRT

human neonatal Fc receptor gene

- FcRn

neonatal Fc receptor

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FNAIT

fetal/neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- HDN

haemolytic disease of the newborn

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphisms

- TBE

Tris-borate EDTA

- VNTR

variable number of tandem repeats

- WBC

white blood cell

References

- 1.Kristoffersen EK, Matre R. Co-localization of the neonatal Fc gamma receptor and IgG in human placental term syncitiotrophoblast. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1668–71. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leach JL, Sedmack DD, Osborne JM, Rahill B, Lairmore MD, Anderson CL. Isolation from human placenta of the IgG transporter, FcRn, and localization to the syncitiotrophoblast: implications for maternal–fetal antibody transport. J Immunol. 1996;157:3317–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borvak J, Richardson J, Medesan C, Antohe F, Radu C, Simonescu M, Ghetie V, Ward ES. Functional expression of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, in endothelial cells of mice. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1289–98. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.9.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumberg RS, Koss T, Story CM, et al. A major histocompatibility complex class I-related Fc receptor for IgG on rat hepatocytes. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2397–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI117934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickson BL, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI. Receptor-mediated immunoglobulin G transport across mucosal barriers in adult-life: functional expression of FcRn in the mammalian lung. J Exp Med. 2002;196:303–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haymann J-P, Levraud J-P, Bouet S, et al. Characterization and localization of the neonatal Fc receptor in adult human kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:632–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V114632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cianga P, Cianga C, Cozma L, Ward ES, Carasevici E. The MHC class I related Fc receptor, FcRn, is expressed in the epithelial cells of the human mammary gland. Hum Immunol. 2003;64:1152–9. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu X, Meng G, Dickinson BL, et al. Class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG is functionally expressed in monocytes, intestinal macrophages and dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:3266–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simister NE, Story CM, Chen HL, Hunt JS. An IgG-transporting Fc receptor expressed in the syncytiotrophoblast of human placenta. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1527–31. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward ES, Zhou J, Ghetie V, Ober RJ. Evidence to support the cellular mechanism involved in serum IgG homeostasis in humans. Int Immunol. 2003;15:187–95. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES. Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn. J Immunol. 2004;172:2021–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellinger I, Reischer H, Lehner C, Leitner K, Hunziker W, Fuchs R. Overexpression of the human neonatal Fc-receptor a-chain in trophoblast-derived BeWo cells increases cellular retention of b2-microglobulin. Placenta. 2005;26:171–82. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antohe F, Radulescu L, Gafencu A, Ghetie V, Simionescu M. Expression of functionally active FcRn and the differentiated bidirectional transport of IgG in human placental endothelial cells. Hum Immunol. 2001;62:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00244-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firan M, Bawdon R, Radu C, Ober RJ, Eaken D, Antohe F, Ghetie V, Ward ES. The MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, plays an essential role in the maternofetal transfer of g-globulins in humans. Int Immunol. 2001;13:993–1002. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zupanska B, Brojer E, Richards Y, Lenkiewicz B, Seyfried H, Howell P. Serological and immunological characteristics of maternal anti-Rh(D) antibodies in predicting the severity of haemolytic disease of the newborn. Vox Sang. 1989;56:247–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1989.tb02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dijk BA, Dooren MC, Overbeeke AM. Red cell antibodies in pregnancy: there is no ‘critical titre’. Transfus Med. 1995;4:199–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.1995.tb00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner ML, Bessos H, Fagge T, et al. Prospective epidemiology study of the outcome and cost-effectiveness of antenatal screening to detect neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia due to anti-HPA-1a. Transfusion. 2005;45:1945–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson LM, Hackett G, Rennie J, et al. The natural history of fetomaternal alloimmunization to the platelet-specific antigen HPA-1a (PlA1, Zwa) as determined by antenatal screening. Blood. 1998;92:2280–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaegtvik S, Husebekk A, Aune B, Oian P, Dahl LB, Skogen B. Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia due to anti-HPA 1a antibodies; the level of maternal antibodies predicts the severity of thrombocytopenia in the newborn. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:691–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikulska JE, Simister NE. Analysis of the promoter region of the human FcRn gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1492:180–4. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghavan M, Bonagura VR, Morrison SL, Bjorkman PJ. Analysis of the pH dependence of the neonatal Fc receptor/immunoglobulin G interaction using antibody and receptor variants. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14649–57. doi: 10.1021/bi00045a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou J, Mateos F, Ober RJ, Ward ES. Conferring the binding properties of the mouse MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, onto the human ortholog by sequential rounds of site-directed mutagenesis. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:1071–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laegreid WW, Heaton MP, Keen JE, et al. Association of bovine neonatal Fc receptor alpha-chain gene (FCGRT) haplotypes with serum IgG concentration in newborn calves. Mamm Genome. 2002;13:704–10. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-2219-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tovar D, Faye JC, Favre G. Cloning of the human RHOB gene promoter: characterization of a VNTR sequence that affects transcriptional activity. Genomics. 2003;81:525–30. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabol SZ, Hu S, Hammer DA. Functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Hum Genet. 1998;103:273–9. doi: 10.1007/s004390050816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chevalier D, Cauffiez C, Bernard C, et al. Characterization of new mutations in the coding sequence and 5′-untranslated region of the human prostacyclin synthase gene (CYP8A1) Hum Genet. 2001;108:148–55. doi: 10.1007/s004390000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dooren MC, Engelfriet CP. Protection against RhD-haemolytic disease of the newborn by a diminished transport of maternal IgG to the fetus. Vox Sang. 1993;65:59–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1993.tb04526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Intravenous immunoglobulin mediates an increase in anti-platelet antibody clearance via the FcRn receptor. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:898–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]