Abstract

Cancer immunosuppression evolves by constitution of an immunosuppressive network extending from a primary tumour site to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral vessels and is mediated by several tumour-derived soluble factors (TDSFs) such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). TDSFs induce immature myeloid cells and regulatory T cells in accordance with tumour progression, resulting in the inhibition of dendritic cell maturation and T-cell activation in a tumour-specific immune response. Tumour cells grow by exploiting a pro-inflammatory situation in the tumour microenvironment, whereas immune cells are regulated by TDSFs during anti-inflammatory situations—mediated by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells—that cause the release of IL-10, TGF-β, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) by macrophages. Accumulation of impaired apoptotic cells induces anti-DNA antibodies directed against self antigens, which resembles a pseudo-autoimmune status. Systemic lupus erythematosus is a prototype of autoimmune disease that is characterized by defective tolerance of self antigens, the presence of anti-DNA antibodies and a pro-inflammatory response. The anti-DNA antibodies can be produced by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, which is the result of a hereditary deficiency of complements C1q, C3 and C4, which are involved in the recognition of phagocytosis by macrophages. Thus, it is likely that impaired clearance of apoptotic cells is able to provoke different types of immune dysfunction in cancer and autoimmune disease in which some are similar and others are critically different. This review discusses a comparison of immunological dysfunctions in cancer and autoimmune disease with the aim of exploring new insights beyond cancer immunosuppression in tumour immunity.

Keywords: apoptosis, autoimmune disease, cancer immunosuppression, cancer immunotherapy

Introduction

Cancer immunosuppression that favours tumour progression and metastasis evolves by constitution of an immunosuppressive network, which is mediated by several tumour-derived soluble factors (TDSFs), such as interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and which extends from the primary tumour site to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral vessels.1,2 Tumour-derived VEGF acts as a strong chemoattractant that induces immature myeloid cells (iMCs) from the bone marrow into peripheral vessels, where they are recruited to the tumour site through chemokines and chemokine receptors.3 The iMCs, which include immature dendritic cells (iDCs) and macrophages, are functionally and biochemically modulated in the tumour microenvironment into tumour-associated iDCs (TiDCs) and macrophages (TAMs) that are re-circulated to regional lymph nodes, spleen and peripheral vessels for immune evasion. The immunosuppressive iMCs and increased concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS) inhibit T-cell activation in tumour-specific immune responses.4

Despite the fact that tumour cells generate pro-inflammatory conditions, the immune cells are regulated in an anti-inflammatory environment, which is mediated by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages during the turnover of tumour cells. Although apoptotic cells are removed by phagocytosis of macrophages through the interaction of phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylserine receptor (PSR),5,6 the soluble form of PS, sPS, can interact with the PSR in macrophages and DCs, resulting in the promotion of an anti-inflammatory response by the released mediators IL-10, TGF-β and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which inhibit subsequent activation of DCs and T cells.7 The impaired clearance of apoptotic cells induces anti-DNA antibodies to self antigens that lead to a pseudo-autoimmune status, which provokes a pro-inflammatory response in tumour progression.7 The increased concentration of autoantibodies and iDCs can induce the production of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) that inhibit T-cell function. Thus, it is likely that cancer immunosuppression is produced by TDSF-induced iMCs, an anti-inflammatory response to immune cells triggered by a defective apoptotic cell clearance, and increased concentration of Treg cells.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a prototype of autoimmune disease. It is characterized by defective tolerance to self antigens and increased concentration of autoantibodies to ribonucleoproteins, double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and other cellular constituents, which provoke pro-inflammatory responses.8 Given that the complements C1q, C3 and C4 are involved in the recognition of apoptotic cells for phagocytosis by macrophages, the hereditary deficiency of these complement factors in SLE causes impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, which promotes the production of anti-DNA antibodies.9,10 Indeed, the impaired clearance of apoptotic cells plays a critical role in producing autoimmune disease.11 The accumulated autoantibodies stimulate a pro-inflammatory response in the cells which leads to tissue damage. Nevertheless, the production of autoantibodies cannot be inhibited by Treg cells because they are functionally deficient.12 Concerning the clinical situation associated with a link between cancer and autoimmune disease, recent reports indicate that several autoimmune paraneoplastic syndromes—which are distinct from autoimmune diseases—associated with the production of autoantibodies, were observed in various types of cancer patients.13,14 Based on these findings, the aim of this review is to compare the immunological dysfunctions in cancer and an autoimmune disease, such as SLE. It is hoped that by considering ways to overcome tumour immunosuppression new insights will be gained that may help to break through the immunosuppressive network in cancer immunotherapy.

Cancer immunosuppressive network and cancer-associated autoimmune status

An effective tumour immune response is produced by activation of DCs and presentation of tumour antigen to naive T cells by cross-priming in secondary lymphoid organs such as sentinel lymph nodes (SNs) and spleen.15 Recent studies indicate that DCs have a dual function in immune regulation—cross-priming of T cells and immunosuppression by iDCs.3,16 The iDCs are derived from iMCs in bone marrow induced by TDSFs, such as VEGF, IL-3 and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), which are recruited to the primary tumour site, as well as immature macrophages activated through chemokines and chemokine receptors.17 These immature DCs and macrophages at the primary tumour site are functionally and biochemically modulated to TiDCs and TAMs that contribute to tumour immune privilege.18,19

The immunosuppressive activity of iMCs is exerted by the increased activity of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and arginase I (ArgI) to produce ROS that inhibit T-cell proliferation and lead to apoptosis.4,20–22 Tumour-derived IL-10 and TGF-β increase the activity of ArgI in TAMs,23 and PGE2 increases the activity of IDO in the tumour microenvironment.24 IDO is an enzyme for metabolizing tryptophan, which is required for T-cell proliferation,25 whereas ArgI is an enzyme that metabolizes l-arginine to ornithine and urea, and the polyamine oxidation from ornithine down-regulates IL-2 production, which in turn inhibits T-cell proliferation.26 In addition, l-arginine is also metabolized to nitric oxide and hydroxide by inducible nitric oxide synthase to inhibit T-cell proliferation.27 Thus, these metabolizing enzymes expressed by TiDCs and TAMs are able to exert immunosuppressive activity in primary tumour sites. The tumour-educated TiDCs and TAMs are distributed to secondary lymphoid organs, such as SNs, spleen and peripheral vessels, resulting in the evolution of an immune evasion as the result of the immunosuppressive network and accompanied by tumour progression and metastasis (Fig. 1). In fact, several previous studies indicated that increased suppressive iMCs were observed in peripheral blood and SNs of patients with various types of cancers, including breast, head and neck, and lung cancer.28

Figure 1.

Cancer immunosuppressive network initiated from primary tumour site and extending to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral vessels. Tumour-derived soluble factors (TDSFs), such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), act as strong chemoattractants that induce immature myeloid cells (iMCs), including immature DCs (iDCs) and macrophages, from bone marrow. The iMCs are recruited to a tumour site in which they are biochemically and functionally modulated, whereby they gain immunosuppressive activity and resistance to apoptosis in the tumour microenvironment. Tumour-associated immature DCs (TiDCs) and macrophages (TAMs) can be re-circulated to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral vessels in the immunosuppressive network, whereas some of the tumour-associated DCs (TADCs) are committed to apoptosis. VEGF inhibits differentiation of thymic precursors, which leads to thymic atrophy.

Given that pro-inflammatory responses enhance tumour growth, pro-inflammatory conditions play an important role in tumour progression. In contrast, the immune cells such as DCs and macrophages, function in anti-inflammatory conditions. Clearance of dead and unnecessary cells during proliferation is crucial for cell turnover in homeostasis, but in cancer cells, clearance of apoptotic cells is impaired by one of the TDSFs, soluble phosphatidylserine (sPS). Tumour-derived sPS interacts with the phosphatidylserine receptor in DCs as well as macrophages whereby engulfment by DCs and macrophages is inhibited. Further, the interaction of sPS with PSR in macrophages promotes a release of anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10, TGF-β and PGE2 whereby the immune cells are shifted to an anti-inflammatory situation.7 Impaired clearance of apoptotic cells produces autoantibodies, which contribute to provoking a pro-inflammatory situation in tumour cells. It should be noted that the impaired apoptotic cells produce anti-DNA antibodies, which can promote the production of Treg cells, leading to functional inhibition of T cells.29 The enforced pseudo-autoimmune status promotes not only a pro-inflammatory response in tumour cells but also inhibits T-cell function in immune evasion. Previous reports have shown that autoantibodies have been detected in various types of cancer patients against p53 tumour suppressor gene products,30,31 surviving,32 and other proteins.33,34 Furthermore, increased concentrations of Treg cells were observed in line with tumour progression.35,36 It should be noted, however, that these autoantibodies in cancer patients are derived from genetic abnormalities such as mutations because anti-p53 antibodies are rarely detected in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren syndrome.37

In addition, as a method for exploiting the production of autoantibodies, it is well known that serological analysis of recombinant complementary deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) expression libraries (SEREX) is a powerful approach to identify immunogenic cancer-associated proteins using antibodies that are present in the serum of cancer patients.38 Antigens can be screened with a panel of allogenic sera from other patients and control individuals. This identifies disease-specific antigens, which may be useful targets for immunotherapy. However, a recent study reported that administration of tumour-associated antigens screened by the SEREX method produced CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells,39 which suppressed the activity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a mouse tumour model, suggesting that tumour antigens derived from impaired clearance of apoptotic cells are able to produce a pseudo-autoimmune status in cancer patients, which is characterized by increases in autoantibodies and Treg cells.

Dysregulated immune response in SLE

SLE is an example of an autoimmune disease, which is characterized by defective tolerance to self antigens and an increase in anti-DNA antibodies, mediated by polyclonal B-cell activation as a result of the hereditary complement deficiency of C1q, C3 and C4. The autoantibodies also promote a pro-inflammatory response, as shown by overexpression of the immunostimulatory cytokine IL-6.40 Although the molecular mechanism for production of autoantibodies has not been elucidated, recent reports indicate that the complement factors C1q, C3 and C4 are necessary for the engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages.9,10 These complement factors are important for the recognition of apoptotic cells, which is mediated by the interaction between C3 and C4 and their receptors on macrophages.41 Although it is not yet known what role the surface-expressed C1q plays, it is also critical for the recognition during phagocytosis.42 In fact, effective recognition by macrophages following opsonization of immunoglobulin G (IgG) particles with C3 and C4 complement increases both uptake and phagocytosis.43 In addition, the complement factors are required for the activation of B cells in which complements bind to the IgG–antigen immune complexes for production of IgG antibodies. Thus, the complements are critically involved in effective phagocytosis by macrophages, mediated by PS/PSR interaction.

Despite the fact that C1q knockout cells are still engulfed by macrophages, the complement-dependent engulfment for clearance of apoptotic cells is exclusively impaired in SLE patients because activation of the complement in both classical and alternative pathways efficiently increases the recognition of apoptotic cells for phagocytosis.9,44,45 In contrast to cancer cells, the defective apoptotic cell clearance does not produce an anti-inflammatory situation in an autoimmune disease; instead, the impaired apoptotic cells and secondary necrotic cells induce a pro-inflammatory situation in self tissues.46 The engulfment by macrophages and DCs is impaired as a result of the hereditary complement deficiency in SLE patients; however, the DNA–IgG immune complexes are able to activate plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and to produce interferon-α (IFN-α) through the Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9).47 Activation by these chromatin immune complexes occurs by two distinct pathways. One pathway involves dual engagement of the Fc receptor FcγRIII and TLR9, whereas the other is TLR9 independent. Furthermore, there is a characteristic cytokine profile elicited by the chromatin immune complexes that distinguishes this response from that of conventional TLR ligands, notably the induction of B-cell-activating factor of the tumour necrosis factor family (BAFF) and the lack of induction of IL-12.48 The TLR-dependent activation can produce maturation of pDCs, leading to an abnormal immune response, because the CpG motif in the DNA that has immunostimulatory activity is hypomethylated.40,49 Although the CpG motif in DNA is generally methylated in eukaryote cells to inhibit an abnormal immune response, the hypomethylated CpG motif in SLE can provoke an immune response to pDCs and B cells through TLR9, triggered by the impaired apoptotic cells. Activation of pDCs can lead to cross-priming of T cells by self antigens, whereby activated T cells promote defective peripheral tolerance as a result of Treg cell dysfunction, which produces tissue injury in autoimmune disease.50 The B cells are also activated through TLR9, resulting in production of polyclonal IgG antibodies.

Unfortunately, although autoreactive T cells for self antigens are usually eliminated by negative selection in the thymus, the concentration of Treg cells is decreased and dysregulated in SLE, so the tissue injury caused by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) cannot be blocked.51 This is a key difference between autoimmune and pseudo-autoimmune status, showing that while the impaired clearance of apoptotic cells in cancer can promote production of autoantibodies, which leads to an increase in the Treg cells, the number of Treg cells in SLE is decreased and dysfunctional. The reason for the fewer and dysfunctional Treg cells in SLE remains unclear; however, in the mouse model and in other autoimmune diseases, a mutation of the forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3) gene, which is a characteristic and functional marker of Treg cells, has been observed.52 In addition, another recent study reported that loss of tolerance to nuclear antigens was associated with a significantly reduced level of Treg cells that preceded autoantibody production, suggesting a causal relationship with the generation of autoreactive T cells. This finding indicates that a specific genetic defect is responsible for lupus pathogenesis by inducing autoreactive T cells to break self-tolerance, and that this genetic defect is also associated with a decreased number of regulatory T cells.53 Although studies involving Treg cells in autoimmune disease are less abundant, several autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis and SLE, have been shown to have a normal or decreased frequency of Treg cells; however, the inhibitory effect for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and their cytokine production was decreased or deleted, which allowed a defective immunological tolerance.51,54

Immunological ignorance and tolerance

A tumour-specific immune response is regulated by tumour antigen level and maturation stages of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as DCs. Many solid tumours, such as sarcomas and carcinomas, express tumour-specific antigens that can serve as targets for immune effector T cells. Nevertheless, the overall immune surveillance against such tumours seems relatively inefficient. Tumour cells were capable of inducing a protective cytotoxic T-cell response if transferred as a single-cell suspension. However, if they were transplanted as small pieces of tumour, they readily grew because the tumour antigen level can be modulated in the tumour microenvironment.55 Thus tumour cells are surrounded by non-tumour cells, including bone-marrow-derived cells such as iMCs and non-bone-marrow-derived cells such as fibroblasts, endothelium and extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM binds tumour antigen,56 and fibroblasts and endothelial cells compete with DCs for the antigen,57 whereby many tumour antigens are down-regulated, thus allowing tumour progression.58 Further, these stromal cells increase interstitial fluid pressure in the tumour, resulting in escape from immune attack by effector cells.59 In these situations, insufficient levels of tumour antigen are largely ignored by T cells, even though T-cell function is suppressed by iMCs in the tumour microenvironment. In addition, because the decreased level of tumour antigen is still attributed to the impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, the production of autoantibodies and increased concentration of Treg cells inhibit T-cell activation. In contrast, sufficient levels of tumour antigen produce an immune response, which is mediated by mature DCs presenting tumour antigens to T cells by cross-priming. However, even in the presence of sufficient levels of tumour antigen, immature MCs inhibit maturation of DCs and T-cell activation, resulting in immunological tolerance.60 Thus, it is likely that tumour immune evasion is mediated not only by immunological ignorance because of a decreased level of tumour antigen but also by immunological tolerance because of inhibition of T-cell activation by iMCs.

In the case of an autoimmune disease such as SLE, sufficient levels of self antigens produce a dysregulated immune response, which is mediated by a defective apoptotic cell clearance. The pDCs activated through TLR9 are able to present self antigens to T cells, whereby CTLs are produced, leading to tissue injury.61 It is likely that not only the provoked abnormal immune response to self antigens, initiated by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells as a result of hereditary complement deficiency, but also dysfunctional Treg cells, which are not directly connected to increased autoantibodies, provide a dysregulated immune response in patient with autoimmune disease.

Clinical implications associated with exploiting the dysregulated immune response in cancer and autoimmune disease for cancer immunotherapy

The substantial differences in immunological dysregulation between cancer and autoimmune disease are summarized in Table 1. If the dysregulated immune response between cancer and an autoimmune disease such as SLE were caused by an impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, it is likely that induction of a defective immunological tolerance would be critical for the difference in the dysregulated immune response. In cancer, the impaired clearance of apoptotic cells causes accumulation of autoantibodies, which is attributed to the inhibition of T-cell function through increased Treg cells, which play a crucial role in immunological tolerance in cancer cells. Immature myeloid cells from the bone marrow, which are induced by TDSFs acting as chemoattractants, also play a critical role for immunological tolerance. Dendritic cells not only initiate T-cell responses, but are also involved in silencing a T-cell immune response. The functional activities of DC mainly depend on their state of activation and differentiation, that is, terminally differentiated mature DC can efficiently induce the development of effector T cells, whereas iDC are involved in the maintenance of peripheral tolerance. While accumulated iDCs, which are educated at the tumour site, act as functional inhibitors of a tumour-specific immune response in cancer, immature pDCs are activated by Toll-like receptors, which leads to B- and T-cell immune responses in autoimmune disease.62 This is another key difference between the dysregulated immune responses in autoimmune disease and cancer, which are involved in disruption of immunological tolerance and maintenance of immunological tolerance, respectively.

Table 1.

Differences in dysregulated immune response between cancer and autoimmune disease

| Factor | Cancer | Autoimmune disease |

|---|---|---|

| Impaired clearance of apoptotic cells | Inhibition of phagocytosis7 | Impaired function of phagocytosis11 |

| Source of macrophage dysfunction activation9,10 | Soluble PS derived from tumour cells7 | Hereditary defect of complement |

| Macrophage phenotype/susceptibility to apoptosis | M2 macrophage/resistant to apoptosis19 | M1 macrophage/sensitive to apoptosis46 |

| Effect on APCs | Anti-inflammatory response | Pro-inflammatory response |

| Release of anti-inflammatory mediators(TGF-β, IL-10, PGE2)7 | Release of pro-inflammatory mediators(TNF-α, IL-6)40 | |

| Autoantibodies | Tumour antigen30–34 | Self antigen9,10,61 |

| CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells | Increase according to tumour progression35,36 | Decreased/dysfunctional12,50,53,54 |

| Immunological tolerance | Maintained60 | Destroyed51 |

APC, antigen-presenting cells; CTLs, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; IL-6, interleukin-6; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; PS, phosphatidylserine; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumour necrosis factor-α.

Regarding the functional differences between pDCs in cancer and autoimmune disease, the pDCs recruited to the tumour site mediated by the interaction of CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4)/SDF-1 are functionally and biochemically modulated,63 resulting in promotion of pDC-mediated generation of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells, which suggests that pDCs may play an important role in the maintenance of immunological tolerance in cancer patients.64 In fact, pDCs infiltrate the tumour tissue of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and diminish the ability to produce IFN-α in response to CpG motif containing oligonucleotide. Tumour-induced down-regulation of TLR9 was identified as one mechanism that probably contributed to impaired pDC function within the tumour environment. In tumour-draining lymph nodes, the suppression of CpG-induced IFN-α production was less pronounced than in single-cell suspensions of primary tumour tissue.65 Further, tumour-induced immune suppression is mediated by immunological ignorance, which is the result of a decrease in tumour antigen in the tumour microenvironment. In contrast, although the impaired clearance of apoptotic cells causes accumulation of autoantibodies, the accumulation is not associated with an increase in Treg cells, rather the function of Treg cells is dysregulated, whereby a defective immunological tolerance is produced in autoimmune disease (Fig. 2).

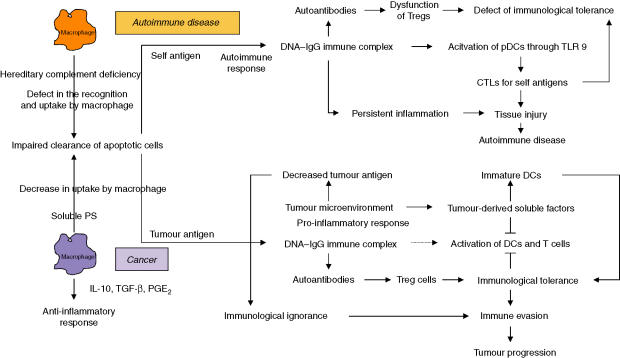

Figure 2.

Different pathways for dysregulated immune responses in cancer and autoimmune disease initiated by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages. In autoimmune disease, defective apoptotic cell clearance causes accumulation of DNA–IgG immune complexes, which provoke an immune response through Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), leading to tissue injury. Unfortunately, the Treg cells are decreased and dysregulated. In contrast, an impaired clearance of apoptotic cells in cancer produces autoantibodies, which increase the regulatory T (Treg) cells and inhibit T-cell activation, causing immunological tolerance. The immunological tolerance is produced by tumour-derived soluble factors (TDSFs) and immature dendritic cells (iDCs), which inhibit DC and T-cell activation, and exclusively inhibit the DNA–IgG immune complex-induced pro-inflammatory responses needed for an immune response. Immunological ignorance is produced by reduced levels of tumour antigens.

CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells play a crucial role in regulating an immune response for maintaining immune homeostasis.66 Naturally occurring Treg cells represent a subset of Treg cells that suppress immune responses through a cell–cell contact mechanism without specific antigen stimulation.66 In comparison, antigen-induced Treg cells mediate immune suppression either through cell–cell contact or through secretion of soluble factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β.66,67 Since the inhibition of production of autoantibodies against self antigens plays a major role in regulating an immune response by Treg cells, the increased concentrations of autoantibodies and immunosuppressive cytokines in cancer promote an increase in Treg cells. Indeed, the increased autoantibodies and Treg cells in peripheral blood are observed in various types of cancer patients in accordance with tumour progression.35,36 The function of these Treg cells has been reported to be inhibition of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, which is involved in establishing immunological tolerance in cancer immunosuppression. The immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, derived from tumour cells, induce Treg cells,68 which activate the activity of IDO for inhibition of T-cell function. Thus, it seems that increased Treg cells in advanced cancer are produced not only by iDCs, IL-10 and TGF-β but also are a result of the increased autoantibodies caused by impaired clearance of apoptotic cells. Functional and molecular characterization of Treg cells has been made possible by the recent association of cell markers, such as CD25,69 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4),70 glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor (GITR),71 and Foxp3 gene product,68 with immunoregulatory activity, which affects both anti-tumour immunity and autoimmunity.72

Given that the increased Treg cells suppressed T-cell function in tumour immune evasion, the inhibition by Treg cells may modulate the functional immune suppression. CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells express the inhibitory molecule CTLA4 that antagonizes the costimulatory molecule CD28, which is activated by the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 in APCs.73 Engagement by CD28 enhances T-cell activation, proliferation, and IL-2 production. CTLA4 binds to CD80 and CD86, but with greater affinity than it binds to CD28,74 and inhibits T-cell activation by interfering with IL-2 secretion and IL-2 receptor expression.75 The anti-CTLA4 antibody inhibits the functional activity of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells, resulting in immunostimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.76 In fact, treatment with human anti-CTLA4 antibody (MDX-010) in conjunction with peptide vaccination of metastatic melanoma patients increased the tumour-associated antigen-specific immune response to CD8+ T cells and led to partial tumour shrinkage.77,78 However, several severe grade 3/4 autoimmune diseases, including dermatitis, enterocolitis, hepatitis and hypophysitis, were observed. In addition, because CD25 is identical to IL-2 receptor-α (IL-2Rα) chain, the anti-IL-2Rα antibody also inhibits the functional activity of CD4+ CD25+ Treg cells. This antibody is known as denileukin diftitox (Ontak) and has clinical applications in CD4+ CD25+ Treg cell-expressing T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma.79 Despite the fact that denileukin diftitox is effective in relapsed or refractory CD25+ and CD25– B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas and is well-tolerated,80 treatment with denileukin diftitox induced toxic epidermal necrolysis in follicular large cell lymphoma.81 Furthermore, administration of denileukin diftitox does not appear to eliminate regulatory T lymphocytes or cause regression of metastatic melanoma.82 Indeed, the functional inhibition of Treg cells targeting CTLA4 and IL-2Rα using monoclonal antibody may modulate the immunosuppressive activity by breaking immunological tolerance. However, an induced severe autoimmune disease is inevitable for cancer patients. More importantly, because cancer immunosuppression is derived from both immunological tolerance and ignorance, it should be remembered that immunological ignorance still exists as a critical factor for producing immune evasion. Further, the immunological tolerance is also derived from the inhibitory action of iMCs on DCs and T cells.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) is involved in another important mechanism in the control of immunosuppression-associated tumours. Developing tumours suppress the induction of pro-inflammatory danger signals through mechanisms involving Stat3, leading to impaired DC maturation which, in turn, provides the developing tumour with a potential mechanism by which to escape immune detection.83 A recent study showed an enhanced function of DCs, T cells and natural killer (NK) cells in tumour-bearing mice with Stat3–/– haematopoietic cells, and that tumour regression required immune cells.84 Targeting Stat3 with a small-molecule drug induced T-cell-dependent and NK-cell-dependent growth inhibition of established tumours.84 Further, targeted disruption of Stat3 signalling in APCs resulted in priming of antigen-specific CD4+/– T cells in response to an otherwise tolerogenic stimulus in vivo.85 Thus, Stat3 signalling provides a novel molecular target for the manipulation of immune activation/tolerance in autoimmunity and cancer immunotherapy.

During the past two decades, several modalities for cancer immunotherapy have been used, and some considerable developments have been observed in the discovery of tumour antigens and tumour-associated antigens, which induce tumour-specific immune responses. These antigens are crucial for the success of the emerging cancer vaccines. Nevertheless, the results of clinical trials on cancer vaccination are not satisfactory.86 The reason for the disappointing results may be one of several factors involved in tumour immune evasion. However, given that a cancer immunosuppressive network initiated from the primary tumour site produces immunological ignorance and tolerance in step with tumour progression, it is unlikely that immunotherapy alone would be able to disrupt the tolerance and ignorance in advanced cancer. Most of the cases given immunotherapy have failed previous treatment with anticancer drugs, and the immunosuppressive network is established. Rather, cancer immunotherapy should be used as a primary treatment targeting a reduced number of cancer cells or residual cells in combination with surgery and chemoradiation. Removal of the primary site followed by disruption of the immunosuppressive network is necessary and critical for improving the tumour immune response in cancer patients. Indeed, neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer87 and neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for cervical cancer88 showed tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and an enhancement of the immune competency of tumour-draining lymph nodes in which induction of massive tumour cell death might be a trigger for provoking a tumour-specific immune response.

Concluding remarks

Immunological tolerance in cancer and autoimmune disease has opposite effects in the patient: in cancer patients it stimulates the growth of the cancer and is bad for the patient, in patients with autoimmune disease immunological tolerance may stop the attack by autoantibodies and thereby benefit the patient. In fact, cancer cells are able to exploit a pseudo-autoimmune status (cancer-associated autoimmune disease) and induce immunological tolerance by producing autoantibodies to tumour antigens derived from impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, resulting in an increase in regulatory T cells. However, cancer-associated immunological tolerance is not mediated only by Treg cells, but rather by the evolution of the immunosuppressive network that extends from the primary tumour site to secondary lymphoid organs and peripheral vessels and is constituted by TDSFs and iDCs. It is unlikely that the induction of autoimmune disease can be the ultimate treatment for cancer patients. Instead, a tumour-specific immune response should be induced by disrupting or modulating the immunosuppressive network as a primary treatment in combination with other treatment modalities. Although the various molecular mechanisms involved in disrupting the immunosuppressive network in cancer patients still require clarification, we are approaching the time when it may be possible to use immunotherapy as a primary systemic cancer treatment.

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- ArgI

arginase I

- BAFF

B-cell-activating factor of the tumour necrosis factor family

- CTLs

cytotoxic T lymphocytes

- CTLA4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- Foxp3

forkhead box protein P3

- iDCs

immature dendritic cells

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN-α

interferon-α

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IL

interleukin

- IL-2Rα

IL-2 receptor-α

- iMCs

immature myeloid cells

- NK cells

natural killer cells

- pDCs

plasmacytoid DCs

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- PSR

phosphatidylserine receptor

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor 1

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- SNs

sentinel lymph nodes

- sPS

soluble phosphatidylserine

- Stat3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TAMs

tumour-associated macrophages

- TDSFs

tumour-derived soluble factors

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TiDCs

tumour-associated iDCs

- TLR9

toll-like receptor 9

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:263–27. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang L, Carbone DP. Tumor–host immune interactions and dendritic cell dysfunction. Adv Cancer Res. 2004;92:13–27. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)92002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Immature myeloid cells and cancer-associated immune suppression. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:293–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0280-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kusmartsev S, Nefedova Y, Yoder D, Gabrilovich DI. Antigen-specific inhibition of CD8+ T cell response by immature myeloid cells in cancer is mediated by reactive oxygen species. J Immunol. 2004;172:989–99. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Rose DM, Pearson A, Ezekewitz RA, Henson PM. A receptor for phosphatidylserine-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. Nature. 2000;405:85–90. doi: 10.1038/35011084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li MO, Sarkisian MR, Mehal WZ, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Phosphatidylserine receptor is required for clearance of apoptotic cells. Science. 2003;302:1560–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1087621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K. Cancer cell immune escape and tumor progression by exploitation of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory responses. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:924–33. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.9.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshmukh US, Gaskin F, Lewis JE, Kannapell CC, Fu SM. Mechanisms of autoantibody diversification to SLE-related autoantigens. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:91–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor PR, Carugati A, Fadok VA, et al. A hierarchical role for classical pathway complement proteins in the clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:359–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bijl M, Reefman E, Horst G, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Reduced uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): correlates with decreased serum levels of complement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:57–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.035733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miyasaka K, Aozasa K, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Nagata S. Autoimmune disease and impaired uptake of apoptotic cells in MFG-E8-deficient mice. Science. 2004;304:1147–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1094359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wraith DC, Nicolson KS, Whitley NT. Regulatory CD4+ T cells and the control of autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solans-Laque R, Perez-Bocanegra C, Salud-Salvia A, Fonollosa-Pla V, Rodrigo MJ, Armadans L, Simeon-Aznar CP, Vilardell-Tarres M. Clinical significance of antinuclear antibodies in malignant diseases: association with rheumatic and connective tissue paraneoplastic syndromes. Lupus. 2004;13:159–64. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu521oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sommer C, Weishaupt A, Brinkhoff J, Biko L, Wessig C, Gold R, Toyka KV. Paraneoplastic stiff-person syndrome: passive transfer to rats by means of IgG antibodies to amphiphysin. Lancet. 2005;365:1406–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66376-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochsenbein AF. Immunological ignorance of solid tumors. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;27:19–35. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woltman AM, van Kooten C. Functional modulation of dendritic cells to suppress adaptive immune responses. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:428–41. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0902431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sozzani S, Vecchi A, Locati M, Sica A. Chemokines in the recruitment and shaping of the leukocyte infiltrate of tumors. Semin Cancer Biol. 2004;14:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;27:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balkwill F, Charles KA, Mantovani A. Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:211–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munn DH, Sharma MD, Lee JR, et al. Potential regulatory function of human dendritic cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Science. 2002;297:1867–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1073514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronte V, Serafini P, De Santo C, et al. IL-4-induced arginase 1 suppresses alloreactive T cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:270–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zea AH, Rodriguez PC, Atkins MB, et al. Arginase-producing myeloid suppressor cells in renal cell carcinoma patients: a mechanism of tumor evasion. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3044–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barksdale AR, Bernard AC, Maley ME, Gellin GL, Kearney PA, Boulanger BR, Tsuei BJ, Ochoa JB. Regulation of arginase expression by T-helper II cytokines and isoproterenol. Surgery. 2004;135:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun D, Longman RS, Albert ML. A two-step induction of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase (IDO) activity during dendritic-cell maturation. Blood. 2005;106:2375–81. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1363–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flescher E, Bowlin TL, Talal N. Polyamine oxidation down-regulates IL-2 production by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Immunol. 1989;142:907–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bronte V, Serafini P, Mazzoni A, Segal DM, Zanovello P. 1-arginine metabolism in myeloid cells controls T-lymphocyte functions. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:302–6. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almand B, Resser JR, Lindman B, Nadaf S, Clark JI, Kwon ED, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Clinical significance of defective dendritic cell differentiation in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1755–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ward JM, Nikolov NP, Tschetter JR, Kopp JB, Gonzalez FJ, Kimura S, Siegel RM. Progressive glomerulonephritis and histiocytic sarcoma associated with macrophage functional defects in CYP1B1-deficient mice. Toxicol Pathol. 2004;32:710–18. doi: 10.1080/01926230490885706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai H, Nakano Y, Kiyosawa K, Tan EM. Increasing titers and changing specificities of antinuclear antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:26–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930101)71:1<26::aid-cncr2820710106>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lubin R, Zalcman G, Bouchet L, Tredanel J, Legros Y, Cazals D, Hirsch A, Soussi T. Serum p53 antibodies as early markers of lung cancer. Nat Med. 1995;1:701–2. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohayem J, Diestelkoetter P, Weigle B, Oehmichen A, Schmitz M, Mehlhorn J, Conrad K, Rieber EP. Antibody response to the tumor-associated inhibitor of apoptosis protein surviving in cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1815–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan EM. Autoantibodies as reporters identifying aberrant cellular mechanisms in tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1411–15. doi: 10.1172/JCI14451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomkiel JE, Alansari H, Tang N, et al. Autoimmunity to the M(r) 32,000 subunit of replication protein A in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:752–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer C, Kim GG, Albers A, Hoermann K, Myers EN, Whiteside TL. Characteristics of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in the peripheral circulation of patients with head and neck cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:913–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolf AM, Wolf D, Steurer M, Gastl G, Gunsilius E, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Increase of regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:606–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mariette X, Sibilia J, Delaforge C, Bengoufa D, Brouet JC, Soussi T. Anti-p53 antibodies are rarely detected in serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1672–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liggins AP, Guinn BA, Banham AH. Identification of lymphoma-associated antigens using SEREX. Meth Mol Med. 2005;115:109–28. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-936-2:109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishikawa H, Kato T, Tawara I, et al. Definition of target antigens for naturally occurring CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:681–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krieg AM. CpG DNA a pathogenic factor in systemic lupus erythematosus? J Clin Immunol. 1995;15:284–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01541318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boackle SA, Holers VM. Role of complement in the development of autoimmunity. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2003;6:154–68. doi: 10.1159/000066860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EI. Role of C1q and C1q receptors in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Dir Autoimmun. 2004;7:87–97. doi: 10.1159/000075688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hakansson L, Hallgren R, Venge P. Kinetic studies of phagocytosis. III. The complement-dependent opsonic and anti-opsonic effects of normal and sle sera. Immunology. 1982;47:91–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walport MJ, Davies KA, Botto M. C1q and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunobiology. 1998;199:265–85. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Botto M. Links between complement deficiency and apoptosis. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:207–10. doi: 10.1186/ar301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ren Y, Tang J, Mok MY, Chan AW, Wu A, Lau CS. Increased apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages and impaired macrophage phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2888–97. doi: 10.1002/art.11237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, et al. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for Toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1131–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boule MW, Broughton C, Mackay F, Akira S, Marshak-Rothstein A, Rifkin IR. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent and -independent dendritic cell activation by chromatin-immunoglobulin G complexes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1631–40. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Januchowski R, Prokop J, Jagodzinski PP. Role of epigenetic DNA alterations in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Appl Genet. 2004;45:237–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palucka AK, Banchereau J, Blanco P, Pascual V. The interplay of dendritic cell subsets in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:484–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lan RY, Ansari AA, Lian ZX, Gershwin ME. Regulatory T cells: development, function and role in autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:351–63. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;99:1057–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Y, Cuda C, Morel L. Genetic determination of T cell help in loss of tolerance to nuclear antigens. J Immunol. 2005;74:7692–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. Suppressor T cells in human diseases. J Exp Med. 2004;200:273–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ochsenbein AF, Klenerman P, Karrer U, Ludewig B, Pericin M, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Immune surveillance against a solid tumor fails because of immunological ignorance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;6:2233–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juprelle-Soret M, Wattiaux-De Coninck S, Wattiaux R. Subcellular localization of transglutaminase. Effect of collagen. Biochem J. 1988;50:421–7. doi: 10.1042/bj2500421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savinov AY, Wong FS, Stonebraker AC, Chervonsky AV. Presentation of antigen by endothelial cells and chemoattraction are required for homing of insulin-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;97:643–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spiotto MT, Yu P, Rowley DA, Nishimura MI, Meredith SC, Gajewski TF, Fu YX, Schreiber H. Increasing tumor antigen expression overcomes ‘ignorance’ to solid tumors via crosspresentation by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Immunity. 2002;7:737–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pietras K, Ostman A, Sjoquist M, Buchdunger E, Reed RK, Heldin CH, Rubin K. Inhibition of platelet-derived growth factor receptors reduces interstitial hypertension and increases transcapillary transport in tumors. Cancer Res. 2001;1:2929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahnke K, Schmitt E, Bonifaz L, Enk AH, Jonuleit H. Immature, but not inactive: the tolerogenic function of immature dendritic cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:477–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blanco P, Viallard JF, Pellegrin JL, Moreau JF. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;7:731–4. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000179942.27777.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lang KS, Recher M, Junt T, et al. Toll-like receptor engagement converts T-cell autoreactivity into overt autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2005;1:138–45. doi: 10.1038/nm1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zou W, Machelon V, Coulomb-L'Hermin A, et al. Stromal-derived factor-1 in human tumors recruits and alters the function of plasmacytoid precursor dendritic cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:1339–46. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moseman EA, Liang X, Dawson AJ, et al. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells activated by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induce the generation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;73:4433–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hartmann E, Wollenberg B, Rothenfusser S, et al. Identification and functional analysis of tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6478–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells in immunological tolerance to self and non-self. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:345–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:389–400. doi: 10.1038/nri821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, Lei KJ, Li L, Marinos N, McGrady G, Wahl SM. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25– naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25+ CD4+ regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. CD4+ regulatory T cells in autoimmunity and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:771–8. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wei WZ, Morris GP, Kong YC. Anti-tumor immunity and autoimmunity: a balancing act of regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2004;53:73–8. doi: 10.1007/s00262-003-0444-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fallarino F, Fields PE, Gajewski TF. B7-1 engagement of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 inhibits T cell activation in the absence of CD28. J Exp Med. 1998;188:205–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Linsley PS, Greene JL, Brady W, Bajorath J, Ledbetter JA, Peach R. Human B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors. Immunity. 1994;1:793–801. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Walunas TL, Bakker CY, Bluestone JA. CTLA-4 ligation blocks CD28-dependent T cell activation. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2541–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25+ regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194:823–32. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Phan GQ, Yang JC, Sherry RM, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity induced by cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8372–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533209100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sanderson K, Scotland R, Lee P, et al. Autoimmunity in a phase I trial of a fully human anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 monoclonal antibody with multiple melanoma peptides and Montanide ISA 51 for patients with resected stages III and IV melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:741–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eklund JW, Kuzel TM. Denileukin diftitox: a concise clinical review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:33–8. doi: 10.1586/14737140.5.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dang NH, Hagemeister FB, Pro B, et al. Phase II study of denileukin diftitox for relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4095–102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Polder K, Wang C, Duvic M, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with denileukin diftitox (DAB (389) IL-2) administration in a patient with follicular large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1807–11. doi: 10.1080/10428190500233764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Attia P, Maker AV, Haworth LR, Rogers-Freezer L, Rosenberg SA. Inability of a fusion protein of IL-2 and diphtheria toxin (Denileukin Diftitox, DAB389IL-2, ONTAK) to eliminate regulatory T lymphocytes in patients with melanoma. J Immunother. 2005;28:582–92. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000175468.19742.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang T, Niu G, Kortylewski M, et al. Regulation of the innate and adaptive immune responses by Stat-3 signaling in tumor cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:48–54. doi: 10.1038/nm976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kortylewski M, Kujawski M, Wang T, et al. Inhibiting Stat3 signaling in the hematopoietic system elicits multicomponent antitumor immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:1314–21. doi: 10.1038/nm1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheng F, Wang HW, Cuenca A, et al. Critical role for Stat3 signaling immune tolerance. Immunity. 2003;19:425–36. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00232-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Restifo NP. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat Med. 2004;10:909–15. doi: 10.1038/nm1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Demaria S, Volm MD, Shapiro RL, Yee HT, Oratz R, Formenti SC, Muggia F, Symmans WF. Development of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer after neoadjuvant paclitaxel chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3025–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fattorossi A, Battaglia A, Ferrandina G, Coronetta F, Legge F, Salutari V, Scambia G. Neoadjuvant therapy changes the lymphocyte composition of tumor-draining lymph nodes in cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1418–28. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]