Abstract

Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) are extensively used in vaccine development. Macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) or simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) are the best animal model currently available for acquired-immune-deficiency-syndrome-related studies. Recent results emphasize the importance of antibody responses in controlling HIV and SIV infection. Despite the increasing attention placed on humoral immunity in these models, very limited information is available on rhesus macaque antibody molecules. Therefore, we sequenced, cloned and characterized immunoglobulin gamma (IGHG) and alpha (IGHA) chain constant region genes from rhesus macaques of Indian and Chinese origin. Although it is currently thought that rhesus macaques express three IgG subclasses, we identified four IGHG genes, which were designated IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4 on the basis of sequence similarities with the four human genes encoding the IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 subclasses. The four genes were expressed at least at the messenger RNA level, as demonstrated by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). The level of intraspecies heterogeneity was very high for IGHA genes, whereas IGHG genes were remarkably similar in all animals examined. However, single amino acid substitutions were present in IGHG2 and IGHG4 genes, indicating the presence of IgG polymorphism possibly resulting in the expression of different allotypes. Two IgA alleles were identified in several animals and RT-PCR showed that both alleles may be expressed. Presence of immunoglobulin gene polymorphism appears to reflect the unusually high levels of intraspecies heterogeneity already demonstrated for major histocompatibility complex genes in this non-human primate species.

Introduction

Rhesus macaques are extensively used in biomedical research as models in experimental protocols related to a variety of human infectious diseases,1 including those caused by Helicobacter pylori,2 mycobacteria,3 yellow fever virus,4 dengue virus,5 as well as in the Plasmodium coatneyi/malaria model.6 Macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIV) or simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) are the best animal model currently available for acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) pathogenesis and vaccine development.7 Results from recent studies emphasize the importance of neutralizing responses in controlling HIV or SIV infection. It is now clear that the resistance of SIV239 to antibody-mediated neutralization may be important for evading effective immunological control and for allowing continuous viral replication.8 Passive transfer of high-titred neutralizing antibodies directed against the HIV-1 envelope protein can block the establishment of SHIV infection in monkeys.9,10 On the basis of experiments performed in rhesus macaques, it appears that a passive immunization treatment with a combination of four neutralizing anti-HIVgp120 antibodies represents a promising approach to prevent peri-and postnatal HIV transmission.11 Although it is expected that rhesus macaques will continue to play a major role in AIDS vaccine development, and despite the increased attention placed on humoral responses directed against HIV and SIV, there is limited information on rhesus macaque antibodies.

The variable and constant regions of immunoglobulin or antibody molecules are involved in antigen binding and effector functions, respectively.12 The various immunoglobulin classes are characterized by a different heavy chain constant (CH) region. CH regions are encoded by genes located in the IGH locus downstream of the variable region (IGHV) genes.13 The various CH regions interact with different components of the immune system to elicit inflammatory responses and eliminate the antigens. Antibodies characterized by a gamma heavy chain, or immunoglobulin G (IgG), exist as monomers and represent the major isotype in blood and extracellular fluids, whereas antibodies characterized by an alpha heavy chain, or IgA, represent the major antibody class present in external secretions and are also an important component of serum immunoglobulin.14 In humans, IgG antibodies can be subdivided into four subclasses, which are designated IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 and contain a heavy chain constant region encoded by one of four immunoglobulin heavy gamma (IGHG) genes, designated IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4 genes, respectively.15 The constant regions of IgG1, IgG2 and IgG4, in their secreted forms, consist of three domains (CH1, CH2 and CH3) as well as a hinge region, each encoded by a distinct exon. IgG3 is encoded by three CH exons and two to five hinge exons.12 Human IgA includes two subclasses, IgA1 and IgA2, also consisting of CH1, CH2 and CH3 domains. The IgA hinge region is encoded by sequences located at the beginning of the CH2 exon. Three IgG subclasses are thought to be present in rhesus macaques.16,17 Previously, it has been shown that IgA genes are highly polymorphic in this species.18,19 Here, the characterization of rhesus macaque immunoglobulin genes is extended to show that four and not three IGHG genes are present in this species and that IGHG genes are polymorphic, although at a level less extensive than IgA molecules.

Materials and methods

Blood samples and DNA/RNA extraction

Blood samples (Indian and Chinese Macaca mulatta) were from animals housed at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, Emory University, Atlanta, GA. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Easy-DNA kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was extracted using the QiaAmp RNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The three Indian rhesus macaques were designated RhInA, RhInB and RhInC, whereas the three Chinese animals were designated RhChA, RhChB and RhChC.

Amplification of IgA constant region genes from genomic DNA and total RNA

In a previous study,18 it was demonstrated that the hinge region is the site of highest heterogeneity within rhesus macaque IgA molecules. Therefore, this area was selected for sequencing in this study. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed on whole genomic DNA using primer pairs (IgA5F and IgA6R) and reaction conditions as previously described18 to amplify CH1 and hinge regions of the IGHA gene. The primer IgA5F is located at the intron–exon junction of CH1, whereas the primer IgA6R is located in the CH2 domain downstream of the sequence coding for the hinge. Approximately 1 μg of genomic DNA was used. The amplification reaction was run in a total volume of 100 μl using the HotWaxOptiStart Kit (Invitrogen) and the high-fidelity expanded polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). The reaction contained a final concentration of 60 mm Tris–HCl, pH 9.0, 15 mm (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 mm MgCl2 and 50 pmol each of the primers IgA5F and IgA6R. After an initial denaturation step at 94° for 4 min, the reaction was run for 35 cycles with each cycle consisting of 94° for 1 min, 58° for 1 min and 72° for 2 min. A final step at 72° for 10 min was employed.

Total RNA samples extracted from whole blood were reverse transcribed into cDNA using the First Strand cDNA synthesis kit where Avian Myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase synthesizes the new cDNA strand in the presence of oligo-dT(17) or random primers (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). After an initial denaturation step at 94° for 5 min, the cDNAs were amplified for 40 cycles, with each cycle consisting of 94° for 1 min, 58° for 1 min and 72° for 2 min. A final step at 72° for 10 min was employed. The PCR primers used to amplify the cDNA were RIgA13F (TGACCGTCATAAACTTCCCGC) located in the CH1 exon and IgA6R18 located downstream of the hinge region. Amplification with the RIgA13F and IgA6R primers yields a fragment of 210–259 base pairs. All sequences were obtained twice from two independent PCR or reverse transcription (RT) PCR.

Amplification of IgG constant region genes from genomic DNA

PCR was performed on whole genomic DNA using the primer pairs IgF and IgC2 and reaction conditions as previously described.20 The primer IgF is located at the intron–exon junction of the CH1 exon, whereas the primer IgC2 is located at the 3′ end of CH3 exon. To amplify the IGHC gene, 1 μg of genomic DNA was used. The amplification reaction was run in a total volume of 100 μl using the high-fidelity expanded polymerase (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The reaction contained a final concentration of 60 mm Tris–HCl (pH 9.0), 15 mm (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 mm MgCl2 and 50 pmol each of the primers IgF and IgC2. After an initial denaturation step at 94° for 4 min, the reaction was run for 35 cycles with each cycle consisting of 1 min at 94°, 1 min at 58° and 2 min at 72°, with a final step consisting of incubation at 72° for 10 min. Two independent PCR were performed for each sample and the expected products were cloned and sequenced.

Cloning of amplified gene sequences

For cloning, 100 μl of a PCR was run on a 1% agarose gel. The specific band of interest was excised from the gel, purified and ligated into either the pCRII or the TopoTA vector (Invitrogen). After transformation into the appropriate strain of Escherichia coli, plasmid DNA from at least 10–20 colonies in each sample was amplified. Plasmid DNA was screened on a 1% agarose gel after digestion with EcoRI to confirm the correct size of the DNA fragments. All DNA sequences were determined using the ABI Prism DNA sequencing kit dye-terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction on an ABI model 377 automated sequencer (Perkin Elmer, Branchburg, NJ). Since the sequence of the hinge region is frequently used to discriminate between IgG subclasses, each IgG clone was first sequenced with the internal primer IgC320 to gather nucleotide information on the hinge region. After selection, clones were sequenced using the forward and reverse M13 primers, as well as the IgF and IgC2 primers. The sequence of the hinge region was also used to discriminate between IgA alleles. Thus, each clone was first sequenced with the IgA6 primer. After selection, clones were sequenced using the forward and reverse M13 primers. All sequences were obtained twice from two independent PCR.

Analysis of DNA sequences

Overlapping regions were identified and sequences were edited using the macvector software program (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA). Sequences were aligned with the known IGHA and IGHC genes using the clustal function of the megalign part of the lasergene software package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI). The ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) standardized nomenclature and numbering21 has been used to show and discuss data. The GenBank accession numbers for IGHA and IGHC sequences are AY294614–AY294623 and AY292502–AY292525, respectively.

IGHC cDNA amplification by real-time RT-PCR

Expression of rhesus macaque IgG isotypes was determined by real-time (TaqMan) RT-PCR, based on cDNA amplification in the presence of two primers and a Taqman probe. The TaqMan probe consists of an oligonucleotide with a 5′-end reporter dye and a downstream 3′-end quencher dye. When the probe is intact, the proximity of the reporter dye to the quencher dye results in suppression of the reporter fluorescence. During PCR, forward and reverse primers hybridize to the specific sequence of the target DNA and the TaqMan probe hybridizes to the target sequence within the PCR product. During the amplification process, the Taq polymerase enzyme cleaves the TaqMan probe separating the reporter and quencher dyes. The separation of the reporter dye from the quencher dye results in increased fluorescence for the reporter. This increase in fluorescence (kinetics) is measured by the the spectrofluorimetric thermal cycler (ABI PRISM 7700) and is a direct consequence of target amplification during PCR. The cycle number during PCR that yields fluorescence intensity significantly above the background is designated as the threshold cycle and therefore indicates a positive PCR.

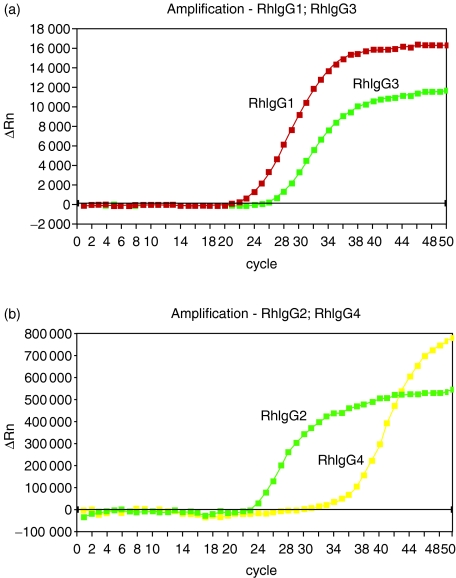

Primers and probes used to amplify rhesus macaque IgG messenger RNA (mRNA) were designed based on our sequence data. For each pair, the forward primer was located in the CH1 domain of the IgGs and the reverse primer was located in the CH2 domain. The probe for each IgG isotype was located in the hinge region, spanning the CH1-hinge junction. The probes for TaqMan were labelled with a fluorescent reporter dye at the 5′ end and with a quencher dye at the 3′ end. The IgG1 and IgG3 probes contained a fluorescent reporter (6-carboxyfluorescein; FAM) and a fluorescent quencher (6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine; TAMRA). The IgG2 and IgG4 probe contained a fluorescent reporter (JOE) and TAMRA. Sequences of primers and probes are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Real-time RT-PCR IGHC primers and probes

| IgG1 primers | |

| IgG1F | ACCAAGGTGGACAAGAGAGTTGA |

| IgG1R | GACGGTCCCCCCAGGAG |

| IgG1 probe | |

| PG1 | FAM-ATAAAAACATGTGGTGGTGGCAGCAAACCT |

| IgG2 primers | |

| IgG2F | GTGGACAAGACAGTTGGGCTC |

| IgG2R | AGACTGATGGTCCCCCCAG |

| IgG2 probe | |

| PG2 | JOE- CATGTCGTTCCACGTGCCCACC |

| IgG3 primers | |

| IgG3F | GCAACGTCGTTCATGAGCC |

| IgG3R | AGGAGTTCAGGTGCTGGGC |

| IgG3 probe | |

| PG3 | FAM-TTGAGTTCACACCCCCATGTGGTGAC |

| IgG4 primers | |

| IgG4F | AGCCCAGCAACACCAAGGT |

| IgG4R | AGTTCAGGTGCTGGGCATG |

| IgG4 probe | |

| PG4 | JOE-TTGAGTTCACACCCCCATGCCCACCAT |

Real-time RT-PCR was carried out using the QIAGEN OneStep RT-PCR Kit. Reactions were set up according to the manufacturer's instructions and run in an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector. RT-PCR conditions for all templates were: initial incubation at 50° for 30 min; second incubation at 95° for 15 min (activation of HotStarTaq ™DNA Polymerase), then 50 cycles of 94° for 30 seconds and of 60° for 30 seconds.

Results

IgA sequences

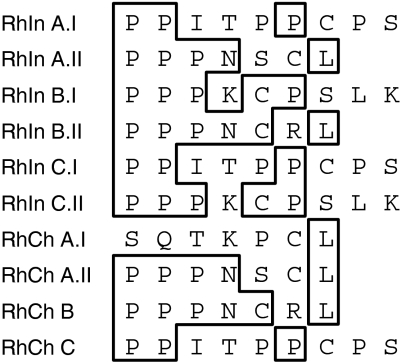

For this study, IGHA and IGHG genes were cloned and sequenced from a total of six rhesus macaques, three of Indian and three of Chinese origin. For the IGHA genes, analysis was limited to the hinge region. Our previous results18 indicate that only one IGHA gene is present in rhesus macaques and that the majority of animals examined possess two alleles of the same gene. In this study, genomic DNA and cDNA were used to demonstrate that when two IGHA alleles are present, both are expressed at least at the mRNA level. Figure 1 shows the IgA amino acid sequences from the various rhesus macaques included in this study. All sequences obtained from DNA were identical to those obtained from cDNA. As expected, a high degree of heterogeneity characterized the hinge region of these antibody molecules. Two different IgA hinge sequences were identified in each of the three Indian rhesus macaques, whereas two IgA hinge sequences were identified in one of the three Chinese animals and only one in the other two Chinese macaques. However, it should be pointed out that because only the hinge region of these molecules was sequenced, the presence of two alleles characterized by similar hinge regions along with amino acid substitutions in other IgA domains cannot be excluded. Furthermore, the presence of one hinge sequence (as compared to two sequences) has been inferred because of identification of only one sequence in a pool of at least 20 colonies obtained from cloning performed on genomic DNA and cDNA from the same animal (all samples were amplified, cloned and sequenced twice). Interestingly, the IgA hinge region sequences present in Indian rhesus macaques were also present in Chinese animals, although in combination with different alleles. Three of the four hinge sequences identified in Chinese rhesus macaques were also present in two Indian animals. Macaque RhInA (Indian) shared one allele with macaque RhChA (Chinese) and the other allele with macaque RhChC (Chinese). Macaque RhInB (Indian) shared one allele with macaque RhChB (Chinese). In addition, macaque RhInB shared one allele with another Indian animal (RhInC).

Figure 1.

Derived amino acid sequences of Indian and Chinese rhesus macaque IgA molecules. The designation of each animal is indicated on the left. When two alleles are present, they are indicated as I and II.

IgG sequences

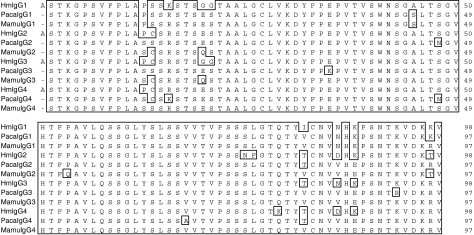

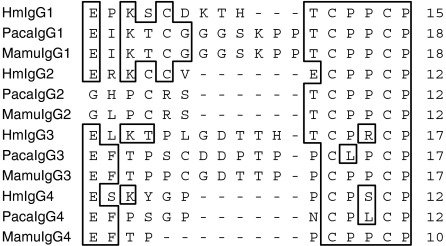

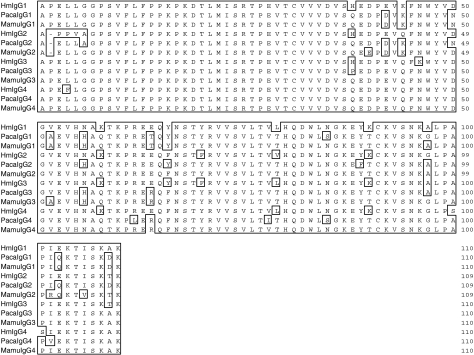

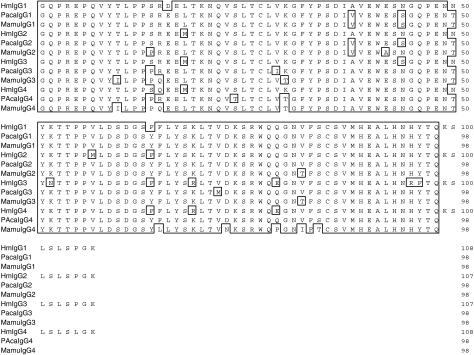

Using primers designed to allow the identification of IGHG genes homologous to the four human and baboon IGHG sequences, four rhesus macaque IGHG genes were amplified, cloned and sequenced. The intron–exon organization of the four genes was inferred from the published sequences of the human IGHG genes. The necessary splicing signals were present at the intron boundaries. The appropriate intronic sequences were also present. The lengths of intron 2 in the four genes were identical to each other and to their human and baboon counterparts (118 nucleotides). However, the lengths of intron 1 in the rhesus macaque genes differed by several nucleotides when compared with the lengths of the corresponding human introns. These differences in intron 1 length varied for each gene. Specifically, the lengths of the rhesus macaque intron 1 were 391, 388, 389 and 389 nucleotides for the IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4 genes, respectively (compared with 388, 392, 391 and 390 nucleotides for the human counterparts and 390, 388, 364 and 366 nucleotides for the baboon counterparts). The length of the rhesus macaque and baboon intron 3 was 97 nucleotides for all four genes, and therefore differed minimally from the length of the third exon of the human intron 3, which consists of 97 nucleotides for the IGHG2 and IGHG4 genes and of 96 and 98 nucleotides for the IGHG1 and IGHG3 genes, respectively. The deduced amino acid sequences (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4) of the four rhesus macaque IGHG genes obtained from a single animal (RhInC) are shown in Fig. 2 (CH1), Fig. 3 (genetic hinge), Fig. 4 (CH2) and Fig. 5 (CH3), along with the deduced amino acid sequences of the four human and four baboon IGHG genes. As expected, cysteines involved in intra-chain disulphide bridges (located at positions 27 and 83 for the CH1 exon, at positions 31 and 91 for the CH2 exon and at positions 27 and 85 for the CH3 exon) as well as the glycosylation site represented by the asparagine located at position 67 of the CH2 domain were conserved in the four macaque sequences.

Figure 2.

Alignment of human (Hu), baboon (Paca) and rhesus macaque (Mamu) CH1-domain-derived amino acid sequences from IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 molecules.

Figure 3.

Alignment of human (Hu), baboon (Paca) and rhesus macaque (Mamu) genetic-hinge-derived amino acid sequences from IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 molecules.

Figure 4.

Alignment of human (Hu), baboon (Paca) and rhesus macaque (Mamu) CH2-domain-derived amino acid sequences from IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 molecules.

Figure 5.

Alignment of human (Hu), baboon (Paca) and rhesus macaque (Mamu) CH3-domain-derived amino acid sequences from IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 molecules.

The majority of the macaque–human differences were clustered in the structural hinge region (Table 2). The structural hinge consists of three segments, the upper, middle and lower hinge. The middle hinge is rigid and contains a variable numbers of cysteine residues, which form interchain disulphide bonds by connecting two parallel polyproline double helices. The majority of differences were located in the upper hinge. Several proline residues that are not present in the human upper hinge regions were present in the corresponding macaque regions. The human IgG3 hinge region is coded by four exons and less frequently by two, three, or five distinct exons separated by short introns.15,22,23 However, in the same way as for baboons,20 only one exon encodes the rhesus macaque IgG3 region. Thus, while the human IgG3 hinge is known to be longer than the other three IgG subclasses, the corresponding macaque region is expected to be similar, in length, to the other subclasses.

Table 2.

Derived amino acid sequences of the upper, core and middle hinge of IgG molecules from humans (Hu) and Macaca mulatta (Mamu)

| Upper Hinge | Core | Lower Hinge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hu-IgG1 | EPKSCDKTHT | CPPC | PAPELLGGP |

| Mamu-IgG1 | EIKTCGGGSKPPT | CPPC | PAPELLGGP |

| Hu-IgG2 | ERK | CCVEPPC | PAPPVAGP |

| Mamu-IgG2 | GLP | CRSTCPPC | PAELLGGP |

| Hu-IgG3 | LKTPLGDTTHT | CPRCP* | |

| EPSKCDTPPPCPRCP | |||

| EPSKCDTPPPCPRCP | |||

| EPSKCDTPPPCPRCP | APELLGGP | ||

| Mamu-IgG3 | EFTPPCDDTTPP | CPPCP | APELLGGP |

| Hu-IgG4 | ESKYGPP | CPSC | PAPEFLGGP |

| Mamu-IgG4 | EFTPP | CPPC† | PAPELLGGP |

Human IgG3 may exhibit two to five repetitions in the hinge. Here, the human hinge is shown with four repetitions.

In rhesus macaques of Chinese origin, the proline at position 8 of the hinge (core) is replaced by an alanine.

The IGHG1, IGHG2 and IGHG3 sequences were highly homologous to those previously published,17 with one amino acid substitution identified in the hinge region and one in the CH2 of the IgG1 sequence, one substitution in the CH1, one in the CH2 and one in the CH3 of the IgG2, and one substitution identified in the CH2 of the IgG3 sequence.

To ascertain whether or not a high degree of heterogeneity is present in rhesus macaques for IgG genes (as well as for IgA genes), the IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4 genes were amplified, cloned and sequenced in the other five animals included in this study. All IGHG genes were remarkably similar in Indian and Chinese rhesus macaques, although it was possible to identify the presence of polymorphisms based on single amino acid substitutions in the IGHG2 and IGHG4 genes of Chinese and Indian macaques. These substitutions are summarized in Table 3, and were located in the IgG2 CH3 domain as well as in the IgG4 CH1, hinge and CH2 domains. Specifically, Indian and Chinese rhesus macaque IgG2 sequences differed for one amino acid at position 14 of the CH3 domain (a proline was present in Indian animals, whereas a serine was found in Chinese animals). A methionine was present at position 68 in the IgG4 CH1 sequence of one of the three Indian rhesus macaque, thus differing from the valine present at the same position in IgG4 sequences from the other five animals. A proline–alanine substitution at the hinge (position 8) differentiated Indian from Chinese animals. In two of the three Chinese macaque IgG4 sequences, an alanine was present at position 61 of the CH2, whereas a valine was present at the same position in the other Chinese and in the three Indian animals. Finally, Indian and Chinese macaques differed for an asparagine (Indian) – histidine (Chinese) substitution at position 65 of the CH2. Taking into account the presence of these substitutions, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 sequences from Indian macaques were 89.9%, 88.0%, 87.9% and 90.1% identical to their corresponding human IgG sequences, whereas the identity of Chinese macaque sequences to their human counterpart was 89.8%, 88.3%, 87.9% and 89.6% for IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4, respectively. Complete non-human primate sequences of all IGHC genes are available only for baboons.20 Rhesus macaque sequences exhibited a high degree of similarity to the baboon counterpart. Specifically, Indian macaque and Chinese macaque IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 molecules were 99.1%, 94.0%, 94.7% and 92.2% identical and 99.1%, 94.1%, 94.8% and 93.3% identical to baboon molecules, respectively. Therefore, IGHC genes were conserved between non-human primate species of Asian (macaque) and African (baboon) origin. Other studies carried out at the protein level16 or by sequencing cDNA17 had identified only three IgG subclasses/genes. Therefore, a rhesus macaque IgG-specific real-time RT PCR was developed to ascertain whether or not the previously reported lack of identification of a fourth subclass/gene was the result of lack of expression of this gene. Figure 6 shows the relative expression levels of the four IGHG transcripts obtained from a representative rhesus macaque (RhInB). By using this PCR, the presence of mRNA was demonstrated for all IGHC genes, thus suggesting that the protein product of the fourth gene might be expressed, although in very limited amounts. Indeed, it is known that the human IgG4 subclass is the one expressed at the lowest level when compared to all the others.12 These results do not indicate the copy number of each individual IGHG transcript present in the sample. However, they do provide the relative expression levels of the various transcripts. On the basis of the cycle numbers, it appeared that IgG1 (ct:21.9) was the transcript present at the highest level, followed by IgG2 (ct:23), IgG3 (ct:25.6) and IgG4 (ct:29.6). Similar transcript ratios were present in samples from all animals analysed in this study.

Table 3.

Amino acid substitutions present in IgG molecules from Indian (RhIn) and Chinese (RhCh) rhesus macaques

| IgG2 CH3-14 | IgG4 CH1-68 | IgG4 Hinge-8 | IgG4 CH2-61 | IgG4 CH2-65 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RhInA | Pro | Met | Pro | Val | Asn |

| RhInB | Pro | Val | Pro | Val | Asn |

| RhInC | Pro | Val | Pro | Val | Asn |

| RhChA | Ser | Val | Ala | Ala | His |

| RhChB | Ser | Val | Ala | Ala | His |

| RhChC | Ser | Val | Ala | Val | His |

Figure 6.

Relative expression levels of the four IGHG transcripts determined by RT-PCR performed using the ‘TaqMan’ detection technology. (a) Detection of rhesus macaque IgG1 and IgG3 from total RNA using a FAM-fluorescent labelled probe; (b) Detection of rhesus macaque IgG2 and IgG4 from total RNA using a JOE-fluorescent labelled probe.

Discussion

Despite the major role that rhesus macaques play in AIDS research, little is known about their antibody molecules. To characterize these molecules further, we have sequenced the hinge region of IGHA genes as well as full-length IGHC genes in a total of six animals, three of Indian origin and three of Chinese origin. The majority of rhesus macaques used in the USA for AIDS research are of Indian descent. However, the number of animals of Chinese origin is steadily increasing, and it is expected that many more Chinese macaques will be utilized in the near future. Species-specific variations in the progression of SIV disease between Chinese and Indian subspecies of rhesus macaques have been identified.24 Despite these differences, the Chinese rhesus macaque subspecies appears to be a suitable AIDS model.25 Therefore, it is necessary to characterize antibody molecules in rhesus macaques from these two geographic origins. Previously, we have demonstrated that rhesus macaque IGHA genes are highly polymorphic.18 This high level of IGHA polymorphism appears common in many non-human primate species.19 Analysis of the available literature indicates that only three IgG subclasses exist in rhesus macaques.16,17 Here, we have shown that four IGHG genes, corresponding to the human IGHG1, IGHG2, IGHG3 and IGHG4, are present in rhesus macaques of either Indian or Chinese descent and that IgG allotypes can be identified in these non-human primates.

High levels of IgA heterogeneity were identified within the group of animals included in this study, with two of the six macaques exhibiting only one hinge sequence (Fig. 1). Three of the four hinge sequences identified in macaques of Chinese descent are also present in two Indian animals. It should be pointed out that the three Indian rhesus macaques are part of a US colony, whereas the three Chinese macaques were recently obtained from a colony in China. Furthermore, the presence of different IgG4 allotypes in Indian and Chinese animals indicates their unrelated origin. These results suggest that, although highly heterogeneous, there is only a limited number of IgA hinge region sequences present in the rhesus macaque population. These sequences are shared by animals of different geographic origin and are present in different combinations in heterozygous animals.

Although it is currently accepted that only three IgG subclasses exist in rhesus macaques, the identification of four IGHC genes is not unexpected. Our recent results show that baboons possess genes corresponding to the four human IGHG sequences.20 We have also identified IGHC genes homologous to the four human IGHG sequences in sooty mangabeys (unpublished observations). The baboon and sooty mangabey IGHG1, IGHG2 and IGHG3 sequences are highly homologous to the three described rhesus macaque IGHG genes. In addition, four IgG subclasses have been described (at the protein level) in cynomolgus monkeys. Therefore, it was reasonable to predict the existence of an IGHG4 homologue in rhesus macaques. Indeed, the primers used in this study were designed to allow amplification of all four expected IGHG genes. RT-PCR results indicate that transcripts from the four IGHG genes can be identified in all macaques involved in this study. Therefore, the IgG4 subclass may be expressed in this species, despite its lack of identification through biochemical methods.16 However, it should be taken into account that, on the basis of its nucleotide and amino acid sequences, the human IgG1 pseudogene would be expected to be expressed at the protein level. For this pseudogene, absence of protein expression appears as a result of the lack of a switch region.26 Therefore, several factors might explain the identification of only three IgG subclasses in macaques.

The four rhesus macaque IgG molecules differ from each other and from their human counterpart primarily at the hinge region (Table 3). The lower hinge is involved in binding the low-affinity Fc gamma receptors.27 Rhesus macaque hinge sequences are different from their human counterpart, with the majority of differences located in the upper hinge, the most flexible segment. The macaque proline-rich upper hinge region may affect flexibility, which is thought to have effects on immune complex formation.28 Therefore, the efficiency of antigen clearance might differ between macaque and human molecules. Because the sequence of the hinge region is also responsible for the susceptibility of antibody molecules to proteolysis,12 it is possible that macaque and human IgG subclasses differ as it relates to sensitivity to proteolysis.

As mentioned above, only one exon encodes the rhesus macaque IgG3 hinge region (whereas multiple exons encode the corresponding human IgG3 region). The resulting shorter hinge might be responsible for functional differences between human and non-human primate IgG3 molecules. Results from a recent study indicate that the extended, more flexible human hinge region confers enhanced HIV-neutralizing ability to IgG3 antibodies.29 Therefore, the absence of the elongated hinge in macaque IgG3 molecules might affect the neutralizing response.

The novel macaque IGHG gene identified as a result of this study would encode a molecule corresponding to the human IgG4 subclass and is polymorphic, thus generating several allotypes that can be differentiated on the basis of single amino acid substitutions. Differences can be identified not only between Indian and Chinese macaques, but also individually within the Indian and Chinese groups of animals. Interestingly, rhesus macaque IgG4 molecules exhibit a proline residue at position 101 of the CH2. In humans, a serine residue at this position is thought to be responsible for the IgG4 inefficiency in complement activation. Human IgG subclasses that bind and activate complement contain a proline residue at position 101.30 It will be interesting to assess whether or not rhesus macaque IgG4 molecules are able to activate complement. It is of note that two allotypic variants were also identified for IgG2 molecules. Comparison of our sequences with the corresponding IGHG1, IGHG2 and IGHG3 sequences described by Calvas and colleagues17 shows the presence of amino acid substitutions for all genes. Furthermore, Glamann and Hirsch31 identified three transcripts corresponding to our IGHC1, IGHC2 and IGHC3 sequences in a single rhesus macaque. These sequences differ from our sequences for several amino acid substitutions located in the CH1, hinge, CH2 and CH3 exons. In humans, only 30 different IgG allotypes have been identified (three IgG1 allotypes, five IgG2 allotypes, 19 IgG3 allotypes and three IgG4 allotypes). Therefore, IgG polymorphism appears more extensive in rhesus macaque populations. IgG variants might be associated with different functional properties. A mutation of a single amino acid in the CH2 of human IgG1 eliminates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity.32 In humans, substitutions of single amino acids abrogate binding to one or more Fc receptors, improve binding to specific receptors or simultaneously improve binding to a receptor and reduce binding to another. IgG1 variants with improved binding to specific Fc receptors result in 100% enhancement in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity activity.33

In conclusion, we have shown that four IGHG genes are present in rhesus macaques, probably encoding four IgG subclasses homologous to those expressed in humans. The geographic origin of these non-human primates does not seem to be associated with major differences in amino acid sequences. However, on the basis of single amino acid substitutions, we have identified two IgG2 allotypes and four IgG4 allotypes in the animals included in this study, thus indicating that high levels of polymorphism exist for immunoglobulin genes in this species. Indeed, it is well-established that rhesus macaques are characterized by an extremely high polymorphism of MHC (Mhcmamu) genes, especially of the Mamu-DRB region.34,35 In this species, high levels of polymorphism have been described also for NKG2 genes.36 The unusual levels of heterogeneity present in rhesus macaque genes encoding molecules of primary importance for the development of effective immune responses have not been found in humans and may reflect an alternative strategy developed by these animals to successfully meet the challenges of host–parasite interactions. Most importantly, such high levels of polymorphism may result in intraspecies differences in pathogen recognition and clearance, thus requiring further characterization and attention when designing and interpreting pathogenesis and vaccine studies carried out in macaque models.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant RR10755, by the Research Program Enhancement from the GSU Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and by the Georgia Research Alliance.

References

- 1.Kennedy RC, Shearer MH, Hildebrand W. Nonhuman primate models to evaluate vaccine safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 1997;15:903–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00277-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansen LM, Solnick JV. Selection for urease activity during Helicobacter pylori infection of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Infect Immun. 2001;69:3519–22. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3519-3522.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attanasio R, Pehler K, McClure HM. Immunogenicity and safety of Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture filtrate proteins in non-human primates. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119:84–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monath TP, Arroyo J, Levenbook I, Zhang ZX, Catalan J, Draper K, Guirakhoo F. Single mutation in the flavivirus envelope protein hinge region increases neurovirulence for mice and monkeys but decreases viscerotropism for monkeys: relevance to development and safety testing of live, attenuated vaccines. J Virol. 2002;76:1932–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.4.1932-1943.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hahn CS, French OG, Foley P, Martin EN, Taylor RP. Bispecific monoclonal antibodies mediate binding of dengue virus to erythrocytes in a monkey model of passive viremia. J Immunol. 2001;166:1057–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tongren JE, Yang C, Collins WE, Sullivan JS, Lal AA, Xiao L. Expression of proinflammatory cytokines in four regions of the brain in Macaca mulatta (rhesus) monkeys infected with Plasmodium coatneyi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;62:530–4. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2000.62.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirsch VM, Lifson JD. Simian immunodeficiency virus infection of monkeys as a model system for the study of AIDS pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Adv Pharmacol. 2000;49:437–77. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(00)49034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson WE, Lifson JD, Lang SM, Johnson RP, Desrosiers RC. Importance of B-cell responses for immunological control of variant strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2003;77:375–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.375-381.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibata R, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, et al. Neutralizing antibody directed against the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein can completely block HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus infections of macaque monkeys. Nat Med. 1999;5:204–10. doi: 10.1038/5568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura Y, Igarashi T, Haigwood N, Sadjadpour R, Plishka RJ, Buckler-White A, Shibata R, Martin MA. Determination of a statistically valid neutralization titer in plasma that confers protection against simian-human immunodeficiency virus challenge following passive transfer of high-titered neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2002;76:2123–30. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2123-2130.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrantelli F, Hofmann-Lehmann R, Rasmussen RA, et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with human monoclonal antibodies prevented SHIV89.6P infection or disease in neonatal macaques. AIDS. 2003;1:30–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nezlin R. General characteristics of immunoglobulin molecules. In: Nezlin R, editor. The Immunoglobulins: Structure and Function. 1. San Diego: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 3–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengten E, Wilson M, Miller N, Clem LW, Pilstrom L, Warr GW. Immunoglobulin isotypes: structure, function, and genetics. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;248:189–219. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59674-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr MA. The structure and function of human IgA. Biochem J. 1990;271:285–96. doi: 10.1042/bj2710285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefranc M-P, Lefranc G. The Immunoglobulin Factsbook. San Diego: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin LN. Chromatographic fractionation of rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) IgG subclasses using DEAE cellulose and protein-A sepharose. J Immunol Methods. 1982;50:319–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvas P, Apoil P, Fortenfant F, Roubinet F, Andris J, Capra D, Blancher A. Characterization of the three immunoglobulin G subclasses of macaques. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:595–610. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scinicariello F, Attanasio R. Intraspecies heterogeneity of immunoglobulin alpha-chain constant region genes in rhesus macaques. Immunology. 2001;103:441–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumiyama K, Saitou N, Ueda S. Adaptive evolution of the IgA hinge region in primates. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1093–9. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attanasio R, Jayshankar L, Engleman CN, Scinicariello F. Baboon immunoglobulin constant region heavy chains: identification of four IGHG genes. Immunogenetics. 2002;54:556–61. doi: 10.1007/s00251-002-0505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefranc MP. IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics database. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:307–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huck S, Fort P, Crawford DH, Lefranc MP, Lefranc G. Sequence of human gamma 3 heavy chain constant region: comparison with the other human C genes. Nucl Acids Res. 1986;14:1779–89. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.4.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dard P, Huck S, Frippiat JP, Lefranc G, Langaney A, Lefranc MP, Sanchez-Mazas A. The IGHG3 gene shows a structural polymorphism characterized by different hinge lengths: sequence of a new 2-exon hinge gene. Hum Genet. 1997;99:138–41. doi: 10.1007/s004390050328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trichel AM, Rajakumar PA, Murphey-Corb M. Species-specific variation in SIV disease progression between Chinese and Indian subspecies of rhesus macaque. J Med Primatol. 2002;31:171–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0684.2002.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling B, Veazey RS, Luckay A, Penedo C, Xu K, Lifson JD, Marx PA. SIV (mac) pathogenesis in rhesus macaques of Chinese and Indian origin compared with primary HIV infections in humans. AIDS. 2002;16:1489–96. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200207260-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bensmana M, Huck S, Lefranc G, Lefranc M-P. The human immunoglobulin pseudo-gamma IGHGP gene shows no major structural defect. Nucl Acids Res. 1988;16:3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.7.3108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radaev S, Sun PD. Recognition of IgG by Fcgamma receptor. The role of Fc glycosylation and the binding of peptide inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16478–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100351200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roux KH, Strelets L, Michaelsen TE. Flexibility of human IgG subclasses. J Immunol. 1997;159:3372–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scharf O, Golding H, King LR, Eller N, Frazier D, Golding B, Scott DE. Immunoglobulin G3 from polyclonal human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) immune globulin is more potent than other subclasses in neutralizing HIV type 1. J Virol. 2001;75:6558–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6558-6565.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Y, Oomen R, Klein MH. Residue at position 331 in the IgG1 and IgG4, CH2 domains contributes to their differential ability to bind and activate complement. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3469–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glamann J, Hirsch VM. Characterization of a macaque recombinant monoclonal antibody that binds to a CD4-induced epitope and neutralizes simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2000;74:7158–63. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.7158-7163.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Idusogie EE, Wong PY, Presta LG, Gazzano-Santoro H, Totpal K, Ultsch M, Mulkerrin MG. Engineered antibodies with increased activity to recruit complement. J Immunol. 2001;166:2571–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site of human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6591–604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Otting N, de Groot NG, Noort MC, Doxiadis GG, Bontrop RE. Allelic diversity of Mhc-DRB alleles in rhesus macaques. Tissue Antigens. 2000;56:58–68. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.560108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doxiadis GG, Otting N, de Groot NG, Noort R, Bontrop RE. Unprecedented polymorphism of Mhc-DRB region configurations in rhesus macaques. J Immunol. 2000;164:3193–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shum BP, Flodin LR, Muir DG, et al. Conservation and variation in human and common chimpanzee CD94 and NKG2 genes. J Immunol. 2002;168:240–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]