Abstract

Previous work has indicated that the dermis and epidermis of skin contains abundant nerve fibres closely associated with Langerhans' cells. We have investigated whether these nerve endings are necessary for inducing and evoking a contact sensitivity (CS) response. Topical application of a general or a peptide (calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P)-specific neurotoxin was employed to destroy the nerve fibres at skin sites subsequently used to induce or evoke the CS response. Elimination of nerve fibres abolished both induction and effector stages of the specific CS response. Denervation did not destroy the local Langerhans' cells, which were observed in increased numbers, or prevent them from migrating to lymph nodes. The local CS response was also abolished by systemic deletion of capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibres, suggesting that the loss of response was not non-specific but associated with the loss of specific nerve fibres. The results indicate that peptidergic nerve fibres are required to elicit a CS response and may be vital to the normal function of the immune system.

Introduction

Epidermal Langerhans' cells are known to mediate the contact sensitivity (CS) response to hapten antigens such as dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). The cells take up and internalize hapten molecules on initial (sensitizing) exposure through the skin. The cells then leave the skin and migrate, via the draining lymphatic vessels, to the paracortical areas of regional lymph nodes (LNs), where hapten antigen is presented to CD4 T lymphocytes. CD4 T cells are required for the CS response to occur and are involved in mediating the secondary response to the hapten molecules by inducing cytokine release in the skin at the point of second exposure.1,2

Nerve fibres in the skin serve a variety of functions (including sensory functions) that are involved in nociception and they also mediate neurogenic inflammation.3–5 It is well documented that nerve fibres mediate the release of proinflammatory cytokines,3,6,7 for example, through stimulation of mast cells.8 Neurotransmitters present in the skin have also been implicated in local immune reactions. Indeed, dermatologists have recognized a relationship between antigen-presenting Langerhans' cells and nerve fibres in a variety of conditions, including contact and delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH), dermatitis, psoriasis and eczema.9–21 Epidermal Langerhans' cells have been shown to be closely associated with calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)-containing nerve fibres.9–12,22–24 The CGRP has also been reported to inhibit both antigen presentation by Langerhans' cells9–12,18 and the DTH response.9–12,25,26 The production and release of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) by mast cells,16 and of interleukin (IL)-10, was induced by CGRP while, in other studies, CGRP was shown to suppress the expression and release of IL-1β, to up-regulate B7-2 (CD86) and to induce IL-12,25 changes that affect Langerhans' cells both directly and indirectly.

The above mentioned studies of the connection between Langerhans' cells and nerve fibres suggested an important interaction underlying both normal and abnormal responses to host challenges. In this study we depleted cutaneous nerve fibres by topical treatment and determined whether this had any consequence on the induction of a CS response, a response that is thought to be dependent on Langerhans' cells in the skin. The results showed that disrupting the nerve supply to the skin, or deleting peptide (CGRP and substance P)-containing nerve fibres throughout the body, prevented mice from developing a CS response.

Materials and methods

Mice

All experiments were sanctioned by the Home Office animal procedures inspectorate. Inbred BALB/c (H-2d) mice, 6–8 weeks of age, were purchased from Harlan UK Ltd (Bicester, UK) and maintained in a 12-hr light/12-hr dark cycle, starting at 08.00 hr, with free access to food and water.

Cutaneous denervation

Mice were anaesthetized with 2% Halothane in a nitrous oxide/oxygen gas mixture and maintained under surgical anaesthesia with 0.5–1.0% Halothane in a nitrous oxide/oxygen gas mixture. A long-lasting analgesic agent, bupranorphine hydrochloride (Vetergesic, Reckitt & Colman, UK), was injected subcutaneously (s.c.), at 0.1 mg/kg, to prevent any pain associated with the neurotoxin treatment (particularly for capsaicin) upon recovery from anaesthesia. Animals were kept under anaesthesia for at least 20 min after neurotoxin treatment. Both control and experimental animals received anaesthesia and analgesia, and the data collected suggests that these agents did not affect the outcome of the CS protocol, which was similar to that reported previously.1 Cutaneous nerve fibres were destroyed with 5 µl of a solution of one of the following: the general neurotoxin, phenol (1.0% in 30% ethanol); the specific neurotoxin, capsaicin (Sigma, Poole, UK), for peptidergic neurones (1 mg/ml in 30% ethanol); or the cholinergic blocking agent, atropine (Sigma) (1 mg/ml in 30% ethanol). Control animals were treated with the vehicle solution of 30% ethanol. The agents were applied to a shaved area of the abdomen and/or to the inner and outer surface of the ear with a pipette tip, ensuring that the whole surface was wetted. Mice were rested for 48 hr prior to further treatment.

Systemic peptidergic denervation

Animals were anaesthetized for at least 30 min after neurotoxin treatment and were given bupranorphine, as described above. All capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibres were destroyed by a s.c. injection, into the scruff of the neck, of 0.25 ml of a 4-mg/ml solution of capsaicin in 10% ethanol + 10% Tween-80 in saline. Control animals were injected with the vehicle solution, i.e. 10% ethanol + 10% Tween-80 in saline.27 Mice were rested for 48 hr prior to receiving further treatment.

Induction and measurement of CS

The procedure to elicit a CS response in the ear was that described previously by Bunce & Bell.1 To ≈4 cm2 of shaved abdomen, 50 µl of a 5% solution of DNCB (2, 4-dinitrochlorobenzene; BDH Chemicals Ltd, Poole, UK) in 100% ethanol was applied to the shaved region using the side of a pipette tip. This was allowed to dry before returning the mouse to its cage. Four days later, the inner surface of the ear was challenged with 10 µl of a 1% solution of DNCB in 100% ethanol (applied with a pipette tip), and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. Ten microlitres of 100% ethanol (vehicle alone) was applied to the opposite ear. Ear thickness was measured, before and after challenge, using a spring-loaded engineer's micrometer (‘ODITEST’ ODT OOT; Kröplin GMBH, Hessen, Germany) by the full release of the spring. Vehicle alone induced a non-specific swelling of ≈45 µm, i.e. the difference in thickness of the left ear measured before and after ethanol (vehicle) application. The CS response of individual mice was recorded as the difference in thickness of the left (vehicle) and right (experimental) ears and expressed as mean µm ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three mice per group. Differences between groups were compared using the Student's t-test.

Test of lymphatics and vasculature

To investigate whether treatment affected the vasculature or lymphatic vessels, treated mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) (tail vein) with 100 µl of 1% Evans blue-conjugated albumin (Sigma) or with an intradermal (i.d.) injection of 50 µl of 1% aqueous Evans blue (Sigma). Mice were killed and their ears removed and examined under a microscope for the appearance of dye in vessels and surrounding tissue.

Immunohistochemistry

Ears were mounted in Cryo-M-Bed (Bright Instruments, Huntingdon, UK) and frozen in isopentane cooled with solid CO2. Sections were cut at 20 µm on a Leica CM1400 cryostat (Leica UK, Milton Keynes, UK), collected on subbed glass microscope slides and allowed to air dry prior to immunohistochemical staining. Epidermal Langerhans' cells were detected with rat anti-mouse I-A/I-E antibody (Pharmingen, Oxford, UK) and nerve fibres with mouse anti-PGP9.5 or rabbit anti-CGRP antibody (NovoCastra, Newcastle, UK). Biotinylated secondary anti-rat IgG (Vector Laboratory, Peterborough, UK) or anti-rabbit IgG (Vector) were visualized with streptavidin-conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) or -tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC) (Sigma) and photographed on a Leica DMLB fluorescence microscope fitted with a Coolsnap digital camera (Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ). Image capture and analysis was carried out using metaview 6.0 software (Universal Imaging Corporation Ltd, Marlow, UK). Langerhans' cell counts were averaged across three fields at 400× magnification on each of three ear sections from at least three ears.

Flow cytometry

To investigate the drainage of Langerhans' cells from skin to LNs, 1% FITC (Sigma) in acetone/dibutylphthalate (1: 1) was applied topically to the shaved abdomen. Four days earlier, skin to the left of the midline had been denervated by the application of capsaicin. Twent-four hours after the application of FITC, the inguinal LNs draining either side of the midline were removed, dispersed into single-cell suspensions and analysed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton-Dickinson, Oxford, UK) for the presence of FITC-containing Langerhans' cells/dendritic cells (DCs). Cervical lymph nodes were used as controls to assess background fluorescence. Cells were electronically gated for size and granularity to exclude debris and dead cells, and 50 000 events were acquired for analysis.

Results

The CS response

The CS response is understood to comprise two stages: the inductive phase and the effector phase. During the inductive phase, the sensitizing antigen is delivered (transported by antigen-presenting cells or free within lymph) to the draining LN and presented to antigen-specific CD4 T cells. The sensitized CD4 T cells are induced to express surface adhesion molecules that subsequently allow them to gain access to sites of inflammation. Application of the sensitizing agent at a later time-point initiates the up-regulation of endothelial adhesion molecules that allow activated T cells to extravasate into the underlying tissue. The effector phase of the response will be elicited if the infiltrating lymphocytes include antigen-specific CD4 T cells. On encountering specific antigen, presented locally by Langerhans' cells or DC, specific CD4 T cells produce cytokines that promote vascular changes which lead to oedema, further cell infiltration and increased thickness. This is a typical CS response that represents, or at least resembles, a DTH response.

Denervation inhibits both the induction and effector stages of CS

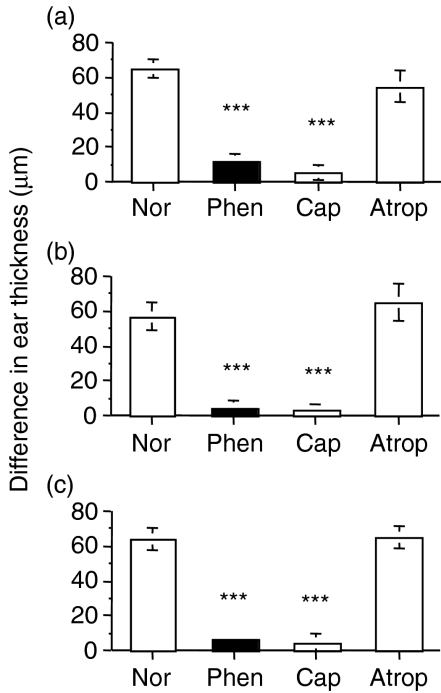

To determine whether the loss of nerve fibres could interfere with the induction of specific CD4 T cells, nerve fibre endings were destroyed on the abdomen of mice by the topical application of dilute phenol28–31 (a pan-neurotoxin) or capsaicin (specific for peptide-containing nerve fibres). Atropine, a competitive antagonist of muscarinic cholinergic receptors, was applied as a control to test for non-specific toxic effects, and ethanol vehicle solution was applied on additional control mice to investigate any non-specific effects of the carrier solution. Two days later, the contact sensitizing agent, DNCB, was applied to the same abdominal site to initiate the primary activation of specific CD4 T cells. Four days later, the CS response was elicited – the right ear was treated with DNCB in ethanol, the left ear with ethanol alone (vehicle) – and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later and expressed as the difference in thickness between the ears. Destroying the cutaneous nerve fibres on the abdomen (the site of sensitization) with either phenol or capsaicin abolished induction of the CS response (Fig. 1a). Atropine treatment, in place of phenol or capsaicin, had no significant effect.

Figure 1.

Cutaneous denervation at the site of sensitization (abdomen), the site of antigen challenge (ear), or both, prevents induction and/or the effector stage of a contact sensitivity (CS) response. To assess the induction/sensitization stage (a), the abdomen of mice were denervated with phenol or capsaicin, or treated with atropine. To assess the effector stage (b), ears of mice were treated with phenol, capsaicin or atropine. To assess the effect of denervation at both the induction and effector stages (c), the abdomen and ears were treated with phenol, capsaicin or atropine. A group of untreated (normal) mice was included in all experiments. All untreated and treated groups were sensitized 2 days later by applying dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) to the abdomen; 4 days later the left ear was challenged by applying DNCB, the right ear was painted with ethanol (vehicle) and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. The difference between left and right ears was recorded. Histograms represent means ± standard error (SE) of at least three mice per group. Test of significance: ***P < 0.001, Treatment versus Normal. Atrop, atropine; Cap, capsaicin; Nor, normal; Phen, phenol.

To determine whether the effector stage of the CS response was altered by denervation, ears, instead of the abdomen, were treated with phenol, capsaicin or atropine, or left untreated. Two days later, as described above, the abdomen of all mice were sensitized to DNCB, ears were challenged with DNCB or vehicle on day 4 and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. Ears that were denervated failed to elicit a response (Fig. 1b). The results showed that the effector phase of the CS response was abolished following local denervation. The atropine treatment did not affect the size of the response. It was noticed that the behaviour of mice treated with DNCB was altered following treatment with phenol and capsaicin. Untreated and atropine-treated mice were observed to scratch their ears after applying DNCB, a known irritant, but no scratching was observed in mice pretreated with phenol or capsaicin. This observation was consistent with the contention that the treatments were successful in destroying the nerve fibres in the ear.

Treating mice at both the induction site (abdomen) and challenge site (ear) with phenol or capsaicin confirmed that deletion of cutaneous nerve fibre endings abolished the CS response (Fig. 1c). Treatment with the anticholinergic agent, atropine, did not block the CS response.

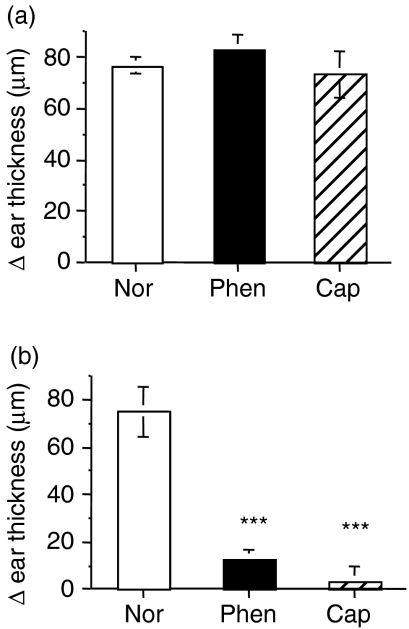

Cutaneous neurotoxin treatment exerts a local and not a systemic effect

In order to test the possibility that denervation might have a generalized systemic effect, we carried out three further experiments. In the first we denervated the abdomen but sensitized the back of the mouse (instead of the abdomen) with DNCB. Challenge of the ear, 4 days, later induced a CS response that was no different to that of untreated control animals (Fig. 2), indicating no evidence of a systemic effect. As denervation was routinely carried out before the initial sensitization, we wanted to determine how delaying the denervation treatment at the site of sensitization (abdomen), or the site of challenge (ear), would affect the CS response. Hence, mice were sensitized on the abdomen and, 2 days later, the abdomen was denervated. Following ear-challenge, after a further 2 days, a normal, positive CS response was evoked (Fig. 3a), suggesting that CD4 T cells were activated early and before denervation treatment could exert an inhibitory effect. In a variation of this protocol, we sensitized the abdomen and, 2 days later, applied neurotoxin to the ear. On subsequent ear-challenge, we found that the CS response was abolished (Fig. 3b), clearly showing that the denervating treatment produced a local effect. In all cases the denervation treatment was linked to the loss of local nerve fibres in the skin and not the result of a systemic effect of the denervating agents.

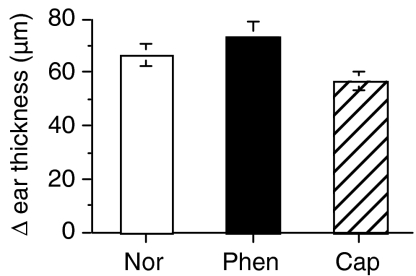

Figure 2.

Denervating the skin (abdomen) at a site that is different to the site of sensitization (the back) does not abolish the dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB)-specific contact sensitivity (CS) response. The abdomen was treated with phenol (Phen) or capsaicin (Cap) or left untreated (Nor). All mice were sensitized on the back with DNCB 2 days later. Four days later, ears of all mice were challenged with DNCB or vehicle, and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. Histograms represent means ± standard error (SE) of at least three mice in each group.

Figure 3.

Denervation exerts a local effect. Mice were sensitized on the abdomen with dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). Two days later, either the abdomen (a) or the ear (b) was treated with phenol (Phen) or capsaicin (Cap) or left untreated (Nor). Two days after treatment (4 days after sensitization) the ears of all mice were challenged with DNCB or vehicle, and ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. Histograms represent means ± standard error (SE) of at least three mice in each group. Test of significance: ***P < 0.001, Treatment versus Normal.

Systemic deletion of capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibres inhibits the CS response

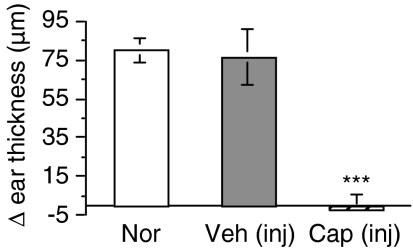

The possibility also exists that local topical application of neurotoxin could have influenced the function of local cells, lymphatic vessels or blood vessels involved in the CS response. To assess this possibility, capsaicin was injected s.c., a procedure that has been shown to destroy the capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibres throughout the body.32–34 Systemic deletion of the capsaicin-sensitive neurones in this way resulted in abolition of the CS response in the ear (Fig. 4), suggesting that the effects were directly related to deletion of the nerve fibres and not to a secondary topical effect of the neurotoxin treatment.

Figure 4.

Systemic deletion of all capsaicin-sensitive nerve fibres abolishes the contact sensitivity (CS) response. Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) with capsaicin solution (or vehicle) to induce a systemic ablation of peptidergic nerve fibres. Two days later, all mice were sensitized with dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) on the abdomen. Four days later, ears of all mice were challenged with DNCB or vehicle, and the ear thickness was measured 24 hr later. Histograms represent means ± standard error (SE) of at least three mice in each group. Test of significance: ***P < 0.001, Treatment versus Normal.

Structural changes in the ears

DNCB-challenged ears from mice sensitized to DNCB were examined by histology and immunocytochemistry to assess the microscopic changes occurring during a CS response and to assess the effects within the ear of local denervation. The increase in ear thickness in normal sensitized mice, elicited by the DNCB ear challenge, was immediately apparent (Fig. 5a,5b). The CS response was characterized by an increase in thickness of the epidermis and dermis, prominent oedema and extensive cellular infiltration. The application of ethanol (vehicle) to the ear induced a slight, but significant, thickening of the dermis, modest oedema and some cellular infiltration (Fig. 5c). Phenol or capsaicin treatment had a similar, non-specific, effect on the skin (not shown) that was indistinguishable from the vehicle treatment. Capsaicin- or phenol-denervated ears (Fig. 5d,e), challenged with DNCB, failed to evoke the level of swelling, oedema and infiltration seen in the atropine- (Fig. 5f) and non-denervated control groups (Fig. 5b).

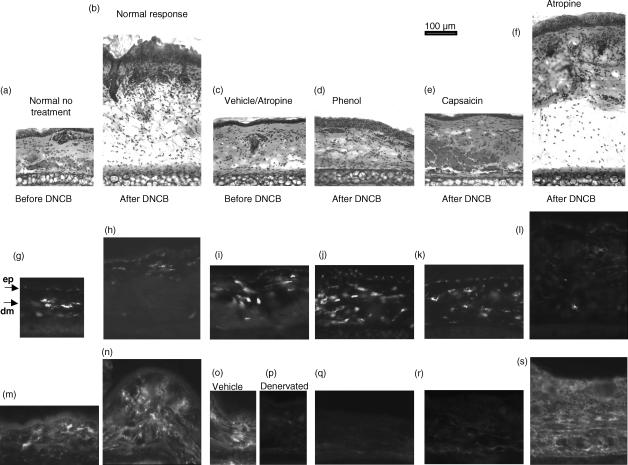

Figure 5.

Local denervation alters the histological and immunohistochemical appearance of ears undergoing a contact sensitivity (CS) response. Ears of mice were untreated, treated with atropine or denervated by topical treatment with phenol or capsaicin. The mice were then sensitized to dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) by applying DNCB to the abdomen, and the CS response was elicited 4 days later by applying DNCB to the ear. Tissue sections (20 µm) were cut by cryostat and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (a–f), anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II (g–l) or anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) (m–s). Ears from normal mice were taken for comparison (a, g, h). The remaining samples were from mice sensitized to DNCB. Ears from the following groups were analysed: untreated ears, 24 hr after antigen challenge (after DNCB: b, h, n); ears receiving vehicle instead of DNCB (c, i, o); phenol-treated ears before (p) and after (d, j, q) DNCB challenge; capsaicin-treated ears after DNCB challenge (e, k, r); and atropine-treated ears after DNCB challenge (f, l, s). Arrows indicate the epidermal (ep) and dermal (dm) layers of the skin (g).

Langerhans' cells/DCs, identified by anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), were present as strongly staining cells in the dermis of normal ears (Fig. 5g), but less abundant in ears that exhibited a strong CS response (Fig. 5h, 5l). Surprisingly, there appeared to be increased numbers of MHC class II-positive DCs in the dermis of phenol- and capsaicin-treated ears (Fig. 5j, 5k). Nerve fibres were identified using mAbs specific for the neuronal marker PGP 9.5 (data not shown) or the neuropeptide CGRP. CGRP-positive staining was present in all tissues (Fig. 5m,5n,5o,5p), except those treated with capsaicin or phenol (Fig. 5q, 5r).

Lymphatic drainage and blood vessels

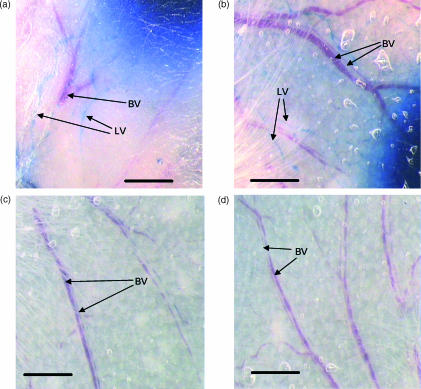

As the induction of a CS response depends on the transport of antigen, via lymphatics, to the draining LN, it was important to determine whether the phenol treatment affected the lymphatic vessels in the area of treatment. Injection i.d. of Evans blue dye was used to identify the lymphatic channels that drain the skin. Two days after treatment with phenol, capsaicin or atropine, Evans blue was injected i.d. at the treated sites. We found no significant difference in the uptake of dye by lymphatic vessels in treated, compared with untreated, skin (Fig. 6a, 6b).

Figure 6.

Photomicrographs of whole mounts of normal (a, c) and phenol-treated (b, d) ears. Following intradermal (i.d.) injection of aqueous Evans blue (a, b) the lymphatic vessels were clearly identifiable filled with blue dye and distinct from the red-coloured blood vessels. There was no evidence for any difference in lymphatic vessels between normal and denervated ears. Following intravenous (i.v.) injection of Evans blue-conjugated albumin (c, d), blood vessels were identified by their blue colour. There was no evidence of leakage of blue dye into the tissue of the denervated ear. Scale bar = 1 mm; BV, blood vessels; LV, lymphatic vessels.

It was also important to establish whether or not phenol treatment had altered the microvascular supply to the ear, which could have influenced the effector stage of the CS response. Evans blue conjugated to albumin was injected i.v. into mice with untreated or phenol-treated ears. The vascular pattern of phenol-treated ears was similar to that of untreated ears (Fig. 6c,6d), with no evidence of leakage of dye, suggesting that the neurotoxin treatment had not adversely affected the integrity of the vasculature.

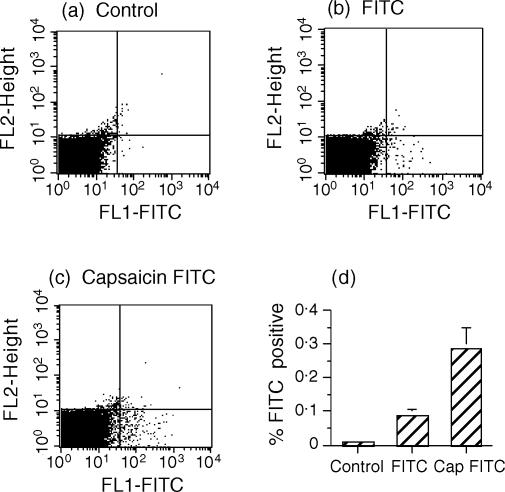

To assess whether denervation of the skin attenuated the movement of antigen-presenting cells to the draining LNs, Langerhans' cells/DCs were labelled in situ by topical application of FITC in acetone-dibutylphthalate.35 Draining inguinal LNs were analysed 24 hr later by flow cytometry for the presence of FITC-labelled cells (Fig. 7). A small (0.089% ± 0.039), but significant (P < 0.01), number of FITC-labelled cells was found in the inguinal LNs (Fig. 7a, 7b, 7d). Denervation of the abdominal skin, 4 days before FITC application, did not prevent the movement of Langerhans' cells/DC (0.289% ± 0.137; Fig. 7c, 7d). Curiously, there was a significant increase (P < 0.02) of labelled cells in LNs draining the denervated, compared with the non-denervated, skin (Fig. 7d).

Figure 7.

Denervation does not prevent Langerhans' cells/dendritic cells (DC) from reaching the draining lymph nodes (LN). Capsaicin (Cap) was applied to the abdomen, but only to the left of the midline; the right half was left untreated. Four days later, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) in acetone/dibutylphthalate was applied to both sides of the midline, mice were killed 24 hr later and LN removed for flow cytometric analysis; (a), (b) and (c) are representative of the profiles analysed. The cervical LN (a) served as a background control (non-draining LN); the right inguinal LN depicts a positive control for the migration of FITC-labelled cells (b); the left inguinal LN assesses the migration of FITC-labelled cells from the capsaicin-denervated site (c). The results were pooled for analysis (d). Histograms represent means ± standard deviation (SD) of FITC-positive cells recorded in the lower right quadrant (n = 5). Test of significance: control versus FITC, P < 0.01; FITC vs. Cap FITC, P < 0.02.

Discussion

To gain a better understanding of the link between nerve fibres and the immune system, the present study investigated the effect that depleting an area of skin of nerve fibres would have on the induction and evocation of a CS response. The major findings were that local treatment of skin sites with a general neurotoxin, phenol, or with capsaicin, which damages only the peptide-containing c-fibre afferent neurons, had the following effects:

destroyed nerve endings in the treated sites;

an increased number of Langerhans' cells/DCs in the area;

prevention of the induction of a CS response;

block of the elicitation of the CS response in sensitized animals; and

no block of the migration of Langerhans' cells/DC from the area to the draining lymph nodes.

The CS response was not blocked by cutaneous denervation of sites not involved in induction or elicitation of the response, suggesting that the effects observed were caused by the local deletion of nerve fibres and not by non-specific or systemic effects of the treatment protocols. The CS response was also abolished by systemic deletion of capsaicin-sensitive neurones, indicating that any local damage by neurotoxin treatment was unlikely to be responsible for the observed abolition of the response. In contrast to our observations, others have reported that systemically injected capsaicin augments the CS response.36,37 The major difference between the two protocols was the induction of CS 2 weeks, rather than 2 days, after denervation, a time-period that could allow substantial readjustment of the cellular components in the denervated skin.

The apparent increase in number of MHC class II-positive DCs was unexpected. Others have described the close association between nerve terminals and Langerhans' cells.10,12,18,23,38 The significance of this association is unclear, although one of the neurotransmitters in these nerve terminals, CGRP, has been shown to inhibit antigen presentation by Langerhans' cells in vitro,10,12,18,39 while another, substance P, has been shown to enhance the function of Langerhans' cells.15,20,40,41 The Langerhans' cell is known to play a vital role in the induction of a CS response. When, for example, Langerhans' cells are destroyed by UV-B irradiation, the induction of CS is lost.42 Interestingly, the acute effect of UV-B irradiation has been shown to be mediated by CGRP which, in turn, causes dermal mast cells to release TNF-α.16 Furthermore, i.d. injection of anti-TNF-α reversed the effect of UV-B and restored the CS response. The same group showed that TNF-α impaired, at least transiently, the ability of Langerhans' cells to present peptide.43 In the present experiments, destroying the nerve fibres on the abdomen before sensitization abolished the induction stage of CS. This was not caused by the destruction of Langerhans' cells, which were abundant at the sites of denervation. Whether CGRP-induced TNF-α was the primary mediator of the impaired CS response remains to be investigated; in our studies, CGRP would have been stimulated by the capsaicin solution applied 2 days previously and not at the time of sensitization.

Activation of specific CD4 T cells normally occurs in LNs and depends on the cellular transport of antigen via lymphatics. Thus, the failure to induce CS could be caused by a block of antigen transport. It was important to determine whether the lymphatic channels that connect with the lymph node remained patent after phenol treatment. The lymphatic drainage from phenol-treated sites was visualized by the uptake in situ of Evans blue dye. The lymph channels were clearly outlined by the dye and resembled those in control skin, suggesting that they were not impaired. Furthermore, capsaicin treatment, which would not be expected to affect lymphatics, was equally efficient in blocking the induction of CS. A more critical test was to determine whether antigen-bearing cells from denervated skin ever reached the draining LN. Using a procedure developed by Cumberbatch et al.,35 FITC-labelled cells from skin were clearly identified in LNs draining normal and denervated skin. Thus, the failure to sensitize for a CS response could not be attributed to impaired antigen transport.

The inability of previously sensitized T cells to evoke a CS response when DNCB was applied to denervated ears was also intriguing. Again, Langerhans' cells are thought to present antigen locally to activated CD4 T cells that infiltrate the site.1 Treatment with phenol or capsaicin did not appear to grossly alter the vasculature. It is possible, however, that activated CD4 T cells failed to infiltrate the site as a result of denervation. A lack of cellular migration has been noted in previous reports documenting a reduced wound healing response in denervated skin. However, the method of denervation probably denied the site of a proper lymphatic drainage system, preventing normal migration.44,45 Alternatively, it is possible that infiltrating CD4 T cells were not stimulated productively by antigen-presenting cells to release cytokines. Perhaps CGRP-containing nerve endings that intimately engage with Langerhans' cells18,23,46 influence the maturation of these DCs and their ability to present antigen. Such an explanation would explain why denervation of these nerve fibres inhibited both the induction and effector stages of the CS response. Previous studies of the interface between nerve endings and Langerhans' cells demonstrated that CGRP was capable of switching off antigen processing and presentation.9,10,12,15,16,18,25,43,47 Further work will be needed to determine whether the loss of the link between Langerhans' cells and CGRP nerve endings directly alters the antigen-presenting function of Langerhans' cells in vivo and/or whether denervation prevents fluid extravasation and infiltration by activated CD4 T cells.

The present study suggests that nerve fibres may play a more direct role with the immune system than generally assumed. Our previous studies have already demonstrated a critical function for nerve fibres present in bone marrow in the control of haemopoietic output.27,48–50 These findings, together with results of other studies, have led us to propose a co-ordinated host defence network utilizing the body-wide network of CGRP-containing and noradrenergic sympathetic nerve fibres.51 Our current data provide strong support for such an integrated system.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Wellcome Trust for support of this work. We thank Rachel Mottram for help with the flow cytometric analysis and Nick Ritchie and Janet Wilson-Walsh for technical assistance. Nazima Ebrahimji carried out the Langerhans' cell counts.

References

- 1.Bunce C, Bell EB. CD45RC isoforms define two types of CD4 memory T cells, one of which depends on persisting antigen. J Exp Med. 1997;185:767–76. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kondo S, Beissert S, Wang B, et al. Hyporesponsiveness in contact hypersensitivity and irritant contact dermatitis in CD4 gene targeted mouse. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12338505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belvisi MG. Sensory nerves and airway inflammation. role of Adelta and C-fibres. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2003;16:1–7. doi: 10.1016/S1094-5539(02)00180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Q, Zou X, Fang L, Willis WD. Sympathetic modulation of acute cutaneous flare induced by intradermal injection of capsaicin in anesthetized rats. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:853–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.00568.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sumikura H, Andersen OK, Drewes AM, Arendt-Nielsen L. A comparison of hyperalgesia and neurogenic inflammation induced by melittin and capsaicin in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;337:147–50. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auais A, Adkins B, Napchan G, Piedimonte G. Immunomodulatory effects of sensory nerves during respiratory syncytial virus infection in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;285:L105–13. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00004.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saade NE, Massaad CA, Ochoa-Chaar CI, Jabbur SJ, Safieh-Garabedian B, Atweh SF. Upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and nerve growth factor by intraplantar injection of capsaicin in rats. J Physiol. 2002;545:241–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarvikallio A, Harvima IT, Naukkarinen A. Mast cells, nerves and neuropeptides in atopic dermatitis and nummular eczema. Arch Dermatol Res. 2003;295:2–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0378-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asahina A, Hosoi J, Beissert S, Stratigos A, Granstein RD. Inhibition of the induction of delayed-type and contact hypersensitivity by calcitonin gene-related peptide. J Immunol. 1995;154:3056–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asahina A, Hosoi J, Grabbe S, Granstein RD. Modulation of Langerhans' cell function by epidermal nerves. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:1178–82. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70203-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asahina A, Hosoi J, Murphy GF, Granstein RD. Calcitonin gene-related peptide modulates Langerhans' cell antigen-presenting function. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1995;107:242–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asahina A, Moro O, Hosoi J, Lerner EA, Xu S, Takashima A, Granstein RD. Specific induction of cAMP in Langerhans' cells by calcitonin gene-related peptide: relevance to functional effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8323–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darsow U, Ring J. Neuroimmune interactions in the skin. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1:435–9. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000011057.09816.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misery L. Neuro-immuno-cutaneous system (NICS) Pathol Biol (Paris) 1996;44:867–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scholzen T, Armstrong CA, Bunnett NW, Luger TA, Olerud JE, Ansel JC. Neuropeptides in the skin: interactions between the neuroendocrine and the skin immune systems. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00307.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niizeki H, Alard P, Streilein JW. Calcitonin gene-related peptide is necessary for ultraviolet B-impaired induction of contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol. 1997;159:5183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan CL, Viglione-Schneck MJ, Walsh LJ, Green B, Trojanowski JQ, Whitaker-Menezes D, Murphy GF. Characterization of unmyelinated axons uniting epidermal and dermal immune cells in primate and murine skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1998;25:20. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1998.tb01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosoi J, Murphy GF, Egan CL, Lerner EA, Grabbe S, Asahina A, Granstein RD. Regulation of Langerhans' cell function by nerves containing calcitonin gene-related peptide. Nature. 1993;363:159–63. doi: 10.1038/363159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh ST, Choi S, Lin WM, Chang YC, McArthur JC, Griffin JW. Epidermal denervation and its effects on keratinocytes and Langerhans' cells. J Neurocytol. 1996;25:513–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02284819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert RW, Granstein RD. Neuropeptides and Langerhans' cells. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1998.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luger TA. Neuromediators – a crucial component of the skin immune system. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;30:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(02)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crivellato E, Travan L, Damiani D, Fusaroli P, Mallardi F. Visualization of PGP 9.5 immunoreactive nerve terminals in the mouse snout epidermis. Acta Histochem. 1994;96:197–203. doi: 10.1016/S0065-1281(11)80177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaudillere A, Misery L, Souchier C, Claudy A, Schmitt D. Intimate associations between PGP9.5-positive nerve fibres and Langerhans' cells. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:343–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller T. Intraepidermal free nerve fiber endings in the hairless skin of the rat as revealed by the zinc iodide-osmium tetroxide technique. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:493–8. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torii H, Hosoi J, Asahina A, Granstein RD. Calcitonin gene-related peptide and Langerhans' cell function. J Invest Dermatol. 1997;2:82–6. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.1997.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Torii H, Hosoi J, Beissert S, Xu S, Fox FE, Asahina A, Takashima A, Rook AH, Granstein RD. Regulation of cytokine expression in macrophages and the Langerhans' cell-like line XS52 by calcitonin gene-related peptide. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:216–23. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Broome CS, Whetton AD, Miyan JA. Neuropeptide control of bone marrow neutrophil production is mediated by both direct and indirect effects on CFU-GM. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:140–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verenkin NL, Soosko VS. Spinal anesthesia and subarachnoid phenol denervation using a modified Lemmon technique. Reg Anesth. 1993;18:226–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haynsworth RF, Jr, Noe CE. Percutaneous lumbar sympathectomy: a comparison of radiofrequency denervation versus phenol neurolysis. Anesthesia. 1991;74:459–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lautt WW, Carroll AM. Evaluation of topical phenol as a means of producing autonomic denervation of the liver. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1984;62:849–53. doi: 10.1139/y84-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minardo JD, Tuli MM, Mock BH, Weiner RE, Pride HP, Wellman HN, Zipes DP. Scintigraphic and electrophysiological evidence of canine myocardial sympathetic denervation and reinnervation produced by myocardial infarction or phenol application. Circulation. 1988;78:1008–19. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burks TF, Buck SH, Miller MS. Mechanisms of depletion of substance P by capsaicin. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2531–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diez Guerra FJ, Zaidi M, Bevis P, MacIntyre I, Emson PC. Evidence for release of calcitonin gene-related peptide and neurokinin A from sensory nerve endings in vivo. Neuroscience. 1988;25:839–46. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mousseau DD, Sun X, Larson AA. An antinociceptive effect of capsaicin in the adult mouse mediated by the NH2-terminus of substance P. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:785–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. In vivo assays of Langerhans' cell migration. In: Robinson SP, Stagg AJ, editors. Methods in Molecular Medicine: Dendritic Cell Protocols. Vol. 64. Ottowa: Humana Press; 2001. pp. 331–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girolomoni G, Tigelaar RE. Capsaicin-sensitive primary sensory neurons are potent modulators of murine delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. J Immunol. 1990;145:1105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Girolomoni G, Tigelaar RE. Peptidergic neurons and vasoactive intestinal peptide modulate experimental delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;650:9–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb49087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Misery L. Langerhans' cells in the neuro-immuno-cutaneous system. J Neuroimmunol. 1998;89:83–7. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seiffert K, Hosoi J, Torii H, Ozawa H, Ding W, Campton K, Wagner JA, Granstein RD. Catecholamines inhibit the antigen-presenting capability of epidermal Langerhans' cells. J Immunol. 2002;168:6128–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niizeki H, Kurimoto I, Streilein JW. A substance, p. agonist, acts as an adjuvant to promote hapten-specific skin immunity. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:437–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Misery L, Bourchanny D, Kanitakis J, Schmitt D, Claudy A. Modulation of substance P and somatostatin receptors in cutaneous lymphocytic inflammatory and tumoral infiltrates. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:238–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Streilein JW, Alard P, Niizeki H. A new concept of skin-associated lymphoid tissue (SALT): UVB light impaired cutaneous immunity reveals a prominent role for cutaneous nerves. Keio J Med. 1999;48:22–7. doi: 10.2302/kjm.48.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bacci S, Nakamura T, Streilein JW. Failed antigen presentation after UVB radiation correlates with modifications of Langerhans' cell cytoskeleton. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:838–43. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12330994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richards AM, Floyd DC, Terenghi G, McGrouther DA. Cellular changes in denervated tissue during wound healing in a rat model. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:1093–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richards AM, Mitsou J, Floyd DC, Terenghi G, McGrouther DA. Neural innervation and healing [letter] Lancet. 1997;350:339–40. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)63391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pergolizzi S, Vaccaro M, Magaudda L, Mondello MR, Arco A, Bramanti P, Cannavo SP, Guarneri B. Immunohistochemical study of epidermal nerve fibres in involved and uninvolved psoriatic skin using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998;290:483–9. doi: 10.1007/s004030050340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torii H, Tamaki K, Granstein RD. The effect of neuropeptides/hormones on Langerhans' cells. J Dermatol Sci. 1998;20:21–8. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(99)00004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Afan AM, Broome CS, Nicholls SE, Whetton AD, Miyan JA. Bone marrow innervation regulates cellular retention in the murine haemopoietic system. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:569–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2733092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyan JA, Broome CS, Afan AM. Coordinated host defense through an integration of the neural, immune and haemopoietic systems. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1998;15:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0739-7240(98)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyan JA, Broome CS, Whetton AD. Neural regulation of bone marrow. Blood. 1998;92:2971–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Downing JE, Miyan JA. Neural immunoregulation: emerging roles for nerves in immune homeostasis and disease. Immunol Today. 2000;21:281–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]