Abstract

Oral administration of antigen induces a state of tolerance that is associated with activation of CD8+ T cells that can transfer unresponsiveness to naïve syngeneic hosts. These T cells are not lytic, but they inhibit development of antibody, CD4+ T helper cell, and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses upon adoptive transfer into naïve, syngeneic mice. In addition, we have shown that depletion of γδ T cells by injection of the anti-δ chain antibody (GL3) down modulates the expression of γδ T-cell receptor (TCR) and inhibits the induction of oral tolerance to ovalbumin. Oral administration of antigen also fails to induce tolerance in TCR δ-chain knockout mice suggesting that γδ T cells play a critical, active role in tolerance induced by orally administered antigen. To further study the contribution of γδ T cells to tolerance, murine γδ T cells were isolated from intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) of the small intestine by stimulation with splenic filler cells, concanavalin A and growth factors. γδ IEL lines demonstrated lytic activity in a redirected lysis assay. γδ T-cell clones express different γδ TCR genes and secrete large amounts of interleukin (IL)-10, but little or no IL-2, IL-4, or interferon-γ. γδ IEL clones expressed transforming growth factor-β1 and macrophage migration inhibitory factor, as well as IL-10, mRNA. Moreover, γδ T-cell clones potently inhibited the generation of CTL responses by secreted molecules rather than by direct cell-to-cell contact.

Introduction

Oral administration of antigen promotes systemic tolerance that is long lived and affects antibody, lymphocyte proliferation, delayed hypersensitivity and contact hypersensitivity responses (reviewed in 1). Using this tolerance model, we found that oral administration of ovalbumin (OVA) did not prime CD8+ cytolytic T-cell precursors but instead specifically inhibited subsequent priming of cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) precursors by parenteral OVA administered in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA).2 Moreover, CD8+ splenic T cells activated by oral antigen suppressed the priming of CD8+ CTL precursors when transferred to naive recipients.2 These findings support previous observations indicating that CD8+ suppressor T cells are activated by oral administration of low doses of antigen (reviewed in 3).

The induction of CD8+ suppressor T cells by oral OVA raises the possibility that antigen presenting cells in the gut may process exogenous antigen via the class I pathway. Soluble proteins and peptides are known to be taken up by villous enterocytes (epithelial cells) in the small intestine for transport to the circulation4 suggesting that they might serve as antigen presenting cells. Villous enterocytes in the small intestine express both major histocompatibility complex class I and II proteins5 and are reported to present soluble antigen to T cells in vitro.6 It is particularly interesting that such antigen-pulsed enterocytes preferentially stimulated CD8+ T cells in rats7 and humans.8 Thus, the enterocytes and CD8+ suppressor T cells may constitute a system that prevents humoral and cell-mediated responses to ingested proteins.

Whether the CD8+ suppressor T cells, which were activated by oral antigen in our system, expressed αβ or γδ T-cell receptor (TCR) was not determined. However, McMenamin et al. showed that exposure of the respiratory mucosa to OVA, activates γδ+, CD8+ splenic T cells, which specifically suppressed immunoglobulin E responses to OVA in rats and mice.9,10 In addition, Mengel et al.11 reported that monoclonal antibody 3A1012 specific for γδ TCR, blocked oral tolerance of antibody and T-cell proliferative responses induced by a single large bolus of OVA. We have observed that treatment of C57BL/6 (B6) mice with antibody to a common epitope expressed by all δ chains (GL3)13 reduced the number of cells expressing γδ TCR in the gut and in the spleen primarily by down-modulating the TCR.14 In addition, GL3 treatment inhibited induction of oral tolerance in humoral responses, priming for interleukin-2 (IL-2) production and the priming of CTL precursors. By contrast, GL3 treatment did not alter immune responses to OVA in mice that were not tolerant. Thus, down-modulation of the γδ TCR is associated with the failure of oral tolerance induction in both humoral and cell mediated responses. Moreover, tolerance was not induced by oral OVA in δ-chain knockout (δ−/−) mice.14,15 The complementary results obtained using two entirely different methods for inducing T-cell deficiency (injection of GL3 in vivo and the δ-chain knockout mice) provide strong support for the hypothesis that γδ T cells play an essential role in development of oral tolerance to soluble antigen.

How oral antigen and γδ T cells collaborate in the induction of low-dose oral tolerance is unknown. Soluble proteins and peptides are taken up by villous enterocytes (epithelial cells that line the small intestine)4 that might participate in tolerance induction.6 Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL) lie in close contact with the villous enterocytes raising the possibility that they might be stimulated by peptides presented by the enterocytes. In the mouse, greater than 90% of the IEL are CD8+ and more than half of these bear γδ TCR.16 Thus, we hypothesize that γδ T cells in the IEL of the small intestine generate a suppressive signal that is broadcast throughout the immune system.

The experiments described in this report were designed to study the immunoregulatory characteristics of murine γδ T cells isolated from the small intestine. γδ T-cell lines grew in cultures of purified IEL that were chronically stimulated with irradiated splenic filler cells, concanavalin A (Con A), and growth factors. The phenotypic and functional characteristics of the γδ T-cell lines and subsequently derived clones are summarized in this report.

Materials and methods

Mice

B6, BALB/c, and SJL mice, 8–12 weeks old, were purchased from the National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center, Frederick, MD). Mice were maintained on standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum in a temperature and light controlled environment. All procedures on animals were conducted according to the principles in the guidelines of the Committee on Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council (NIH publication N. 85-23, revised 1985).

Reagents

Purified chicken egg OVA grade VI was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). CFA containing Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra was obtained from Difco Laboratory (Detroit, MI). The EL4 and P815 cell lines were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD) and the E.G7-OVA cell line was provided by Dr Michael Bevan (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). All cell cultures were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 1 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) and antibiotics, at 37° in 6% CO2 in air. All cell lines were mycoplasma-free.

Isolation and culturing IEL

IEL were isolated from the small intestines of B6 mice as described by Lefrancois and Lycke17 with some modifications. Briefly, the small intestines were removed, flushed with cold calcium and magnesium free Hank's balanced salt solution, and freed of fat, mesentery, and Peyer's patches. The intestines then were cut into small pieces and incubated in calcium and magnesium free Hank's balanced salt solution containing 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) plus 1 mm dithiothreitol, at 37°, with stirring, for 20 min. The released cells were collected, filtered through a nylon wool column, and centrifuged through a 40% Percoll gradient to remove contaminating epithelial cells that float to the top.

Purified IEL (2·5 × 105 cells/ml) were incubated at 37°, 6% CO2 with irradiated (2000 rad) splenocytes (2·5 × 106 cells/ml) and 2·5 µg/ml Con A. The IEL were restimulated every 7 days as described above plus 2 ng/ml IL-2 or IL-4. Under these conditions, the IEL routinely proliferated for several weeks and then largely died off, as reported by Lefrancois.16 However, small numbers of viable lymphocytes persisted in many of these cultures, some of which rapidly expanded after 2–3 months. Such long-term lines were restimulated every 3–4 days at a lower density (105 IEL and 106 irradiated splenocytes/ml) and typically grew 2–5-fold at each passage. Stable IEL lines were cloned by limiting dilution at concentrations of 100, 10, 1, and 0·1 cell/100 µl/well in round-bottomed 96-well plates containing irradiated spleen cells, Con A, and IL-4 in 200 µl of medium. One half the volume of media was removed every 3–4 days and replaced with medium containing fresh spleen cells, Con A, and IL-4. Cloned IEL were cultured at a density of 105 IEL/ml, as described for the bulk lines. All cell lines were maintained free of mycoplasma.

Flow cytometry

IEL were stained with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Fluorochrome conjugates of matched isotypes were used as negative controls in all experiments. All staining was performed in 50 µl of staining buffer (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7·4 containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 0·1% sodium azide) and incubated for 30 min on ice. The cells were washed three times with staining buffer after each treatment and analysed immediately thereafter. Analysis was performed with a FACScan Cytofluorimeter using Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) and the data were analysed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA). Forward angle and side light scatter were used to exclude dead and aggregated cells.

Identification of γδ TCR expressed by clones

Clones were stimulated for 2 days in medium supplemented with 10 units/ml of recombinant human IL-2 and 2 ng/ml murine recombinant IL-4. RNA was then isolated from 5·0 × 106 cells using RNAzol BTM (Tel.Test, Inc, Friendswood, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Next, 10 µg of RNA was treated with 1 unit of DNase I, Rnase-free enzyme (Boehringer Mannheim, Manheim, Germany) in the manufacturer's reaction buffer in a 10 µl volume for 15 min. DNAse I was then inactivated by the addition of 1 µl of 25 mm EDTA and incubation at 65° for 15 min. The entire reaction mixture was then reverse transcribed to make cDNA using the Superscript II Preamplification System For First Strand cDNA Synthesis (Gibco/BRL, Bethesda, MD) with the provided random hexamers. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was then performed using cDNA (1–2 µl), 5·0 µl 10× PCR buffer (200 mm Tris HCl, pH 8·4, 500 mm KCl), 5·0 µl 25 mm MgCl2, 5·0 µl 0·1% gelatin, 1·0 µl 10 mm dinucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), Vγ or Vδ sense primer, and Cγ or Cδ antisense primer (1·0 µl 1250 pmol/µl), 1–5 units Taq DNA polymerase in 50 µl reaction volume. The Vγ and Cγ gene primers were used as shown in Table 1. The Vδ and Cδ primers sequences were used as described by Olive.18 PCR conditions included an initial denaturation step at 94° for 2 min, then 40 cycles of denaturation at 94° for 30 s, annealing at 60° for 1 min, and elongation at 68° for 2 min. A final elongation step at 68° for 7 min was also included. PCR was performed in an Ericomp Deltacycler II system thermocycler. The PCR reaction mixture (10 µl) was then subjected to gel electrophoresis in 2% agarose to resolve PCR amplicons. PCR amplicons were then cloned into the pGEM T-easy vector (Promega, Madison, WS) according to the manufacturers instructions. Plasmid purification from transformed bacterial colonies was then performed using Qiagen columns (Qiagen, Inc. Valencia, CA). PCR amplicons ligated into the pGEM T-easy vector were sequenced using SP6 and T7 primers by the Emory microchemical facility.

Table 1.

Vγ and Cγ primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Vγ 1–3 | GGG CTT GGG CAG CTG GAG CA |

| Vγ 4 | GCA ACC TGA AAT ATC AAT TT |

| Vγ 5 | GAC TCC TGG ATA TCT CAG GA |

| Vγ 6 | GGA ACG AGT CTC ACG TCA CC |

| Vγ 7 | ACA TCC TCC AAC TTG GAA GA |

| Cγ | CTT ATG GAG ATT TGT TTC AGC |

RNAse protection assay

Measurement of cytokine mRNA expression was performed using the Riboquant® multiprobe RNase protection assay system (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Radiolabelled RNA probes were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions using multiprobe template sets, mCK-1 (IL-2, -4, -5, -6, -9, -10, -13, -15, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) L32, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)) and mCK-3b (tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TNF-β, leukotriene-α, IFN-γ, IFN-β, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1), TGFβ2, TGF-β3, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), L32, GAPDH). Probes were hybridized to 10 µg of RNA isolated from respective IEL clones as described above. Hybridization and RNAse digestion were then performed as outlined in the product insert. Protected probes were resolved by electrophoresis through a Novex® 6% Tris-borate-EDTA–urea precast polyacrylamide gel for denaturing nucleic acid analysis (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using the Novex® Mini Cell apparatus (Invitrogen). The migration distance of the RNAse-protected bands was compared to a standard curve of migration distance vs. the log nucleotide length for each undigested probe to determine the identity of protected probes.

Cytokine assay by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Supernatants were collected from IEL cultures, which were stimulated under various conditions described in the text, after 24 hr and assayed for cytokines using paired monoclonal antibodies (PharMingen, San Diego, CA). The biotinylated antibodies were detected with avidin–peroxidase (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) plus 2·2-azino-di-[3-ethyl-benzthiazoline] sulphonate substrate containing H2O2 (Kirkegaard & Perry, Gaithersburg, MD). The colorimetric reaction was read at 405 nm using an automatic microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Menlo Park, CA). The concentration of cytokine was calculated from a standard curve using the appropriate recombinant cytokine (Peprotech, Inc. Rocky Hills, NJ).

Generation of CTL responses in vitro

In some experiments, CTL responses were generated in mixed lymphocyte responses (MLR) cultures containing 2·5 × 105 B6 responder spleen cells stimulated with 10 × 105 irradiated (2000 rad) BALB/c spleen cells in round bottom 96-well tissue culture plates, in a total of 200 µl per well. IEL were serially diluted and added to the cultures, which were incubated for 5 days at 37°, 5% CO2.

In other experiments, draining (inguinal, axillary, and brachial) lymph node cells were obtained from mice injected with 200 µg OVA in CFA intradermally at two sites on the back 10 days earlier. Lymph node cells (6·0 × 106) were plated in 0·9 ml medium/well of a 24-well plate containing a cell culture insert (transparent filter, 0·4 µm pore size) (Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) filled with 0·3 ml medium. γδ or αβ IEL clones (2·0 × 102 cells) were added to the well or cell culture insert. Cultures were stimulated with OVA (20 µg/ml) for 5 days at 37° in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

CTL assays

MLR were assayed in the 96-well plates, which were centrifuged for 2 min at 300 g, the media removed, and the pelleted cells resuspended in 100 µl of fresh media. P815 targets were labelled with Na251CrO4 (Dupont, Boston, MA) and added directly to the plate, at 104 cells in 100 µl per well. OVA-specific CTL were measured using 51Cr labelled EG.7-OVA, an EL4 tumour line transfected with the OVA gene19 at a 100 : 1 effector : target ratio.

In other experiments, the lytic activity of IEL was measured by a method referred to as redirected lysis.20 The P815 mastocytoma cell line, which is an FcR positive line, was used to measure the lytic activity. Briefly, various ratios of IEL were mixed with 51Cr-labelled P815 cells in the presence or absence of 1 µg/ml anti-CD3 antibody (145–2C11) (Pharmingen).

Supernatants were collected after a 4-hr incubation at 37° and radioactivity was detected in a gamma counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Percent specific lysis was calculated as 100 × ([release by CTL − spontaneous release]/[maximal release − spontaneous release]). Maximal release was determined by addition of 1% Triton-X-100 (EM Science, Gibbstown, NJ).

Results

Generation of T-cell lines and clones from IEL of the small intestine

Although γδ T-cell hybridomas have been produced from IEL21 and IEL have been maintained for several weeks by stimulating with immobilized anti-TCR antibody16 to our knowledge there have been no reports describing the establishment of stable, long-term lines of γδ T cells from IEL of the small intestine. To test the hypothesis that γδ T cells of the gut may have immunoregulatory activities, IEL were purified from control and tolerized B6 mice and cultured under a variety of conditions, with and without the tolerizing antigen.

Stable IEL lines were successfully grown in cultures stimulated with irradiated, syngeneic splenic filler cells, Con A, and IL-4 or IL-2. Twenty IEL cultures from independent B6 mice have given rise to stable lines. Eight of these lines contained mixtures of αβ and γδ T cells. In such cultures, the αβ T cells generally grew faster than the γδ T cells and sometimes overgrew them completely. Four IEL lines contained only γδ T cells, four lines contained only αβ T cells, and four contained cells that expressed no TCR but they expressed CD45 and hence were bone marrow-derived cells (not shown). γδ IEL were derived from normal, OVA-immunized, and tolerant mice given OVA orally, but no significant differences have been detected among them and none responded to OVA. Consequently, the lines and clones from the variously treated mice are used interchangeably in this report.

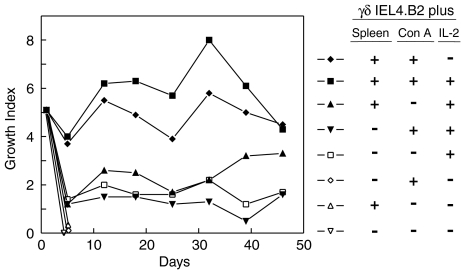

Growth requirements for a representative γδ T cell line (IEL4.B2) are shown in Fig. 1. These cells grew well when cultured with splenic filler cells plus Con A and addition of IL-2 further enhanced this growth. These lines grew moderately well when stimulated with IL-2 with or without filler cells, or Con A. However, the γδ T cells rapidly died when cultured alone, with Con A or with splenic filler cells only. Similar results have been obtained with other γδ T-cell lines and clones (not shown). The γδ T cells grew best when re-stimulated every 3–4 days and routinely expanded three- to eightfold after each stimulation. These lines are not able to survive more than 7 days without re-stimulation (not shown). None of the γδ T-cell lines was stimulated by the self-antigens presented by resting autologous spleen cells. The γδ T-cell lines, derived from mice treated with OVA intragastrically with or without subsequent immunization with OVA in CFA, were not activated by soluble OVA or OVA transfected EL4 cells (not shown). Thus, the epitopes recognized by these γδ T cell lines remain undefined.

Figure 1.

Growth requirements of a γδ IEL line. The γδ IEL4.B2 line was incubated at 105 cells/ml alone or with 106 irradiated spleen cells/ml, 2·5 µg/ml Con A, or 2 ng/ml rIL-2 as indicated above. The cells were harvested 3–4 days later, washed, viable cells counted and the growth index (cell number at end of culture/input cell number) recorded. Growth index on day 0 reflects the growth of the input cells, which were subdivided and grown under the indicated conditions, during the previous cycle.

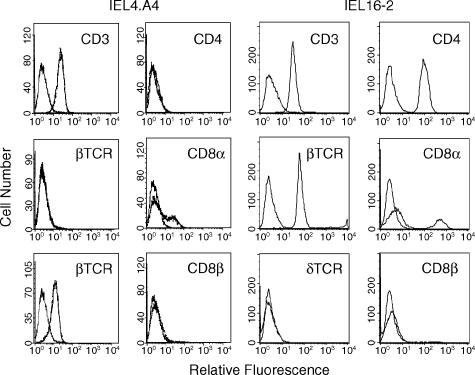

Phenotypic characterization of representative γδ and αβ T cells

The cell surface phenotypes of representative γδ (IEL4.A4) and αβ (IEL 16–2) T-cell lines derived from the IEL are shown in Fig. 2. The γδ IEL expressed CD3, TCR δ-chain, low levels of CD8α, but not CD4 or CD8β. The αβ IEL expressed CD3, TCR β-chain, CD4, CD8α, but not CD8β. A subset within both γδ and αβ T-cell lines expressed CD8αα but not CD8αβ, which is indicative of thymus-independent development.22 This pattern of CD8 expression was observed in several different IEL cell lines. Because 100% of the αβ T-cell line expressed CD4, these results indicate that a subset of the αβ T cells expressed both CD4 and CD8α, a phenotype that has been previously reported.23,24

Figure 2.

Cell-surface antigens expressed by IEL T cell lines. IEL4.A4, a representative γδ IEL line, and IEL16-2, a representative αβ IEL line, were incubated with FITC-labelled isotype control (the left-most curve in each histogram) or antibodies that are indicated in the above flow cytometry histograms.

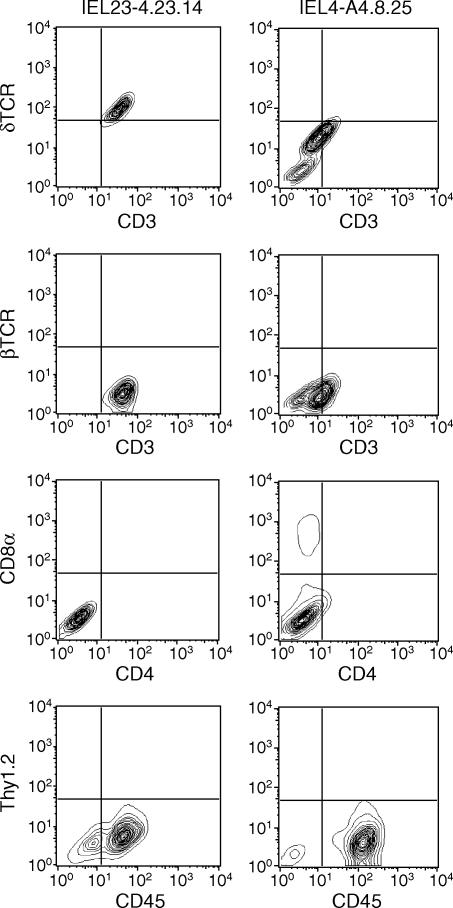

γδ T cells have been cloned by limiting dilution from six independently derived cell lines. Clones derived from two (IEL4.A4 and IEL23-4) bulk lines were subsequently subcloned and analysed for cell-surface phenotype. Representative subclones expressed CD3, TCR δ-chain, and CD45 but not Thy1.2, CD4, or CD8β (Fig. 3). Some subclones, such as IEL23-4.23.14, uniformly expressed CD3 and γδ TCR, whereas others, such as IEL4.A4.8.25, sometimes developed a subset that was CD3 and γδ negative. The CD3 negative cells did not express αβ TCR and are presumed to be γδ T cells that have lost the capacity to express TCR. In addition, a small but detectable number of IEL4.A4.8.25 cells expressed CD8α. The variable expression of CD8α by these γδ T-cell clones is not caused by a contaminating subset because these cells have been cloned and subcloned. Rather, the expression of CD8α by IEL seems to be regulated by yet to be identified culture conditions. The idea that CD8α can be regulated in non-thymus-derived cells is supported by the observation that CD8α expression can be induced in mast cells by nitric oxide.25

Figure 3.

Cell surface antigens expressed by γδ T-cell clones. Two representative γδ IEL subclones (IEL23-4·23·14 and IEL4.A4.8.25) were treated with FITC-labelled antibodies shown on the x-axis and PE-labelled antibodies on the y-axis. Appropriately labelled isotype controls were used to set the quadrants for the negative controls.

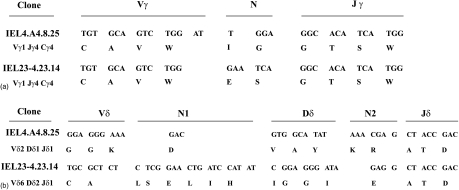

The functional γ- and δ-chains for two independently derived clones, whose functional activities have been extensively studied, were sequenced (Fig. 4). Subclones IEL4.A4.8.25 and IEL23-4.23.14 expressed Vγ1Jγ4Cγ4, which is compatible with the observations that intestinal Vγ region gene expression is diverse but the Vγ1 is a dominant (15–60%) TCR.26,27 IEL4.A4.8.25 expressed Vδ2Dδ1Jδ1 whereas clone IEL23-4.23.14 expressed Vδ6Dδ2Jδ1, which are also among the γ TCR previously associated with intestinal γδ T cells.28 Clone IEL4.A4.8.25 also expressed a non-productive Vδ6Dδ2Jδ1 transcript, whereas clone IEL 23–4·23·14 expressed non-productive Vδ2Dδ1Jδ1 and Vγ7Jγ1Cγ1 transcripts. The observation that each γδ T-cell subclone expressed only one functional γδ TCR supports the interpretation that cloning by limiting dilution was successful.

Figure 4.

Identification of γ and δ chains expressed by two IEL clones. The functional γ- and δ-chains for two independently derived, γδ IEL subclones were cloned and sequenced. The nucleotide sequences and the translated amino acids are depicted above.

Functional characteristics of the γδ T-cell lines

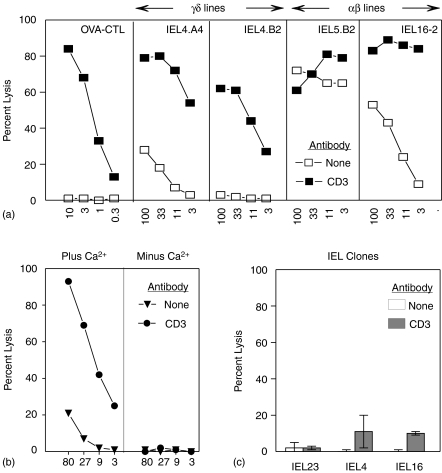

Freshly isolated γδ T cells from the IEL of the small intestine can kill FcR-expressing targets in a re-directed lysis assay.29 Like the OVA-specific CD8+αβ CTL cell line, four of the four stable γδ T cell lines tested were cytolytic for P815 when incubated in the presence of anti-CD320 as illustrated by IEL4.A4 and IEL4.B2 (Fig. 5a). Neither the OVA CTL line nor the γδ T-cell lines killed P815 in the absence of anti-CD3. By contrast, six out of seven αβ IEL lines killed P815 about as well in the presence or absence of anti-CD3, as illustrated by IEL 5.B2, whereas anti-CD3 enhanced the lysis of P815 by IEL16-2 (Fig. 5a). Redirected lysis by γδ IEL lines was Ca2+ dependent, as illustrated in Fig. 5(b), suggesting that it is mediated by the perforin pathway rather than a FasL pathway.30,31 In contrast to the IEL lines, three of the three γδ IEL clones tested illustrated by IEL4.A4.8.25 and IEL 23-4.23.14) exhibited only very low levels of cytotoxicity in the redirected lysis assay (Fig. 5c). The lytic activity of the IEL lines was lost with time in culture as illustrated by the loss of activity seen in the αβ IEL 16-2 (Fig. 5c compared to Fig. 5a).

Figure 5.

Lytic activity of IEL T cells. The lytic activity of various T cells was measured at various effector : target ratios by incubation with 51Cr-labelled P815 plus or minus 1 μg/ml anti-CD3 antibody. The activity of an OVA-specific CTL line and the indicated γδ and αβ IEL lines are shown in (a) while that of clones IEL23-4.23.14 (IEL23) and IEL4.A4.8.25 (IEL4) are compared to the αβ 16-2 line in (c). The lytic activity of the γδ IEL22/N4 line was measured in the presence or absence of 1·8 mm CaCl2 (b).

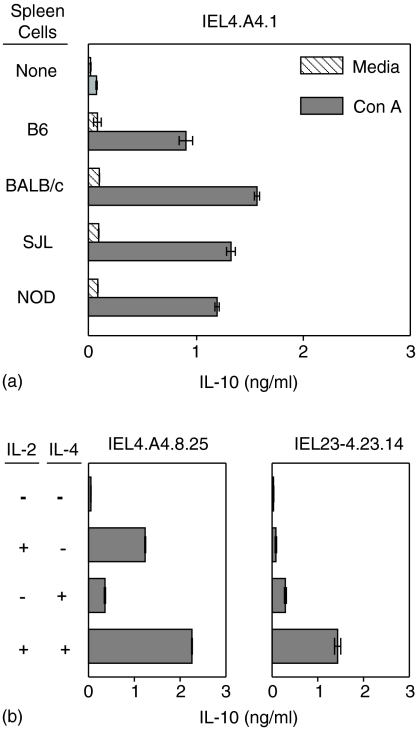

γδ T cells have the capacity to produce a variety of cytokines including IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10 and TNF-α depending on the source and conditions of activation.32–34 Six of seven γδ T-cell lines tested and clones from three such lines, as illustrated by IEL4.A4.1, secreted IL-10 upon stimulation with syngeneic B6 splenic filler cells and Con A but not when incubated with either Con A or spleen cells alone (Fig. 6a). Irradiated spleen cells stimulated with Con A did not secrete IL-10 (not shown). The source of the filler cells appears to be irrelevant since the γδ T-cell clone secreted IL-10 when stimulated by Con A in cultures containing a variety of irradiated allogeneic spleen cells (Fig. 6a). αβ IEL lines and clones made little if any IL-10 under the same conditions (not shown). Two other γδ IEL clones (IEL4.A4.8.25 and IEL 23-4.23.14) also secreted IL-10 when stimulated with spleen cells and Con A (not shown) and when incubated with IL-2 and/or IL-4 in the absence of spleen cells (Fig. 6b). Production of IL-10 was additive in cultures of most γδ subclones stimulated with both IL-2 and IL-4, as illustrated by IEL 4.A4.8.25 but occasionally IL-2 and IL-4 synergized in the induction of IL-10 as seen with clone IEL23-4.23.14. The γδ IEL lines and clones secreted little if any detectable IFN-γ or IL-4 (not shown). The αβ IEL have not been studied as extensively, but the few tested secreted IFN-γ but no IL-10 or IL-4 (not shown).

Figure 6.

Requirements for secretion of IL-10 by γδ IEL clones. γδ clone, IEL4.A4.1, was incubated at 2·5 × 105 cells/ml with or without 2·5 × 106/ml irradiated (2000 rad) spleen cells from the indicated strains of mice plus or minus 2·5 μg/ml Con A (a). γδ IEL4.A4.8.25 and γδ IEL23-4.23.14 were incubated at 105 cells/ml alone or with 20 U/ml IL-2 and/or IL-4 (b). Supernatants were collected after 24 h and assayed for IL-10 by ELISA. (Note that IEL4.A4.1 and IEL4.A4.8 are sister clones from the same bulk line; IEL4.A4.8.25 is a subclone of IEL4.A4.8 and IEL23-4·23.14 is a subclone of clone IEL23-4·23.)

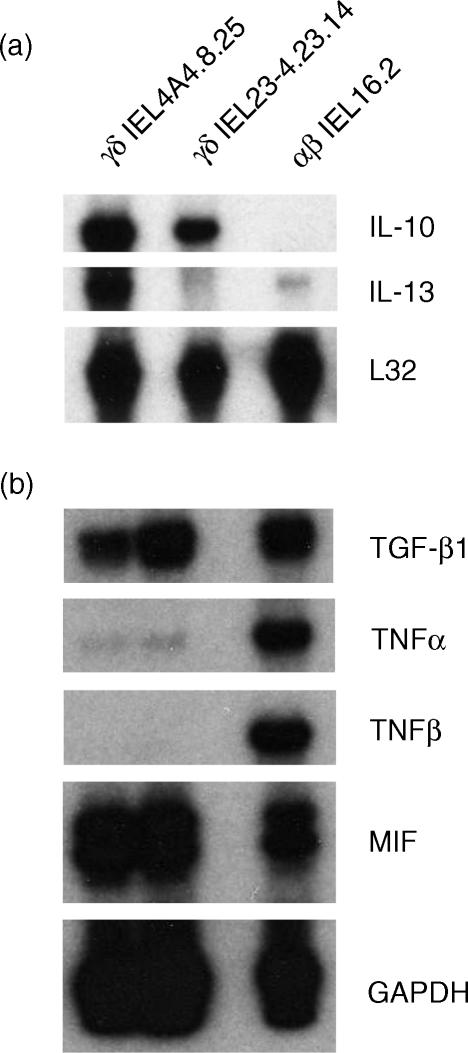

Representative clones also have been examined for cytokine mRNA expression after stimulation with IL-2 plus IL-4, in the absence of spleen cells, using an RNAse protection assay. Two independently derived γδ T-cell subclones (IEL4.A4.8.25 and IEL23-4.23.14) gave reproducibly strong signals for IL-10 and varied signals for IL-13 (Fig. 7a). Weak and variable signals were detected for IL-15, IL-2, IL-6 and IFN-γ in the γδ clones (not shown). The αβ T-cell line (16.2) expressed a weak signal for IL-13 but little or no signal for IL-10, IL-15, IL-2, IL-6, or IFN-γ. The αβ clone displayed strong signals for TNF-α and TNF-β, whereas the γδ IEL did not (Fig. 7b). All three cell clones expressed mRNA for TGF-β1 and MIF.

Figure 7.

Expression of cytokine mRNA by γδ and αβ IEL. The indicated riboprobes were hybridized to 10 μg RNA isolated from αβ IEL4.A4.8.25 and IEL23-4.23.14 and αβ IEL16.2, digested with RNAse, and resolved by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Riboprobes for the housekeeping genes, L32 or GAPDH, were used to verify loading of equivalent amounts of RNA onto the gel.

Immunosuppressive activities of the γδ T-cell clones

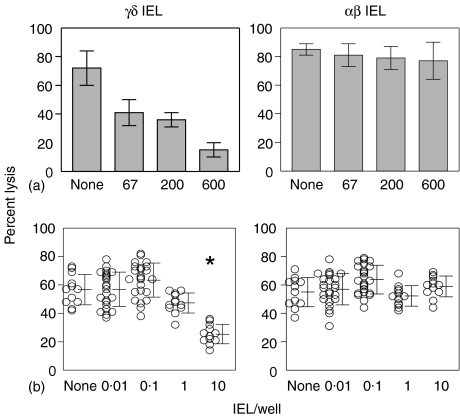

To test the immunosuppressive activity of clones derived from the IEL, γδ and αβ cells were added to 96-well plates containing B6 responder spleen cells and irradiated BALB/c stimulators. These MLR cultures were assayed for CTL responses by adding 51Cr labelled target cells directly to the 96-well plates and counting the supernatant fluids. γδ IEL profoundly suppressed the lytic activity generated in the MLR, whereas the αβ IEL did not suppress the lytic activity at equivalent numbers of cells (Fig. 8a). A limiting dilution analysis revealed that as few as 10 γδ IEL/well inhibited the development of CTL responses (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8.

Immunosuppressive activity of representative IEL clones. The suppressive activity was assessed by adding the indicated numbers of γδ IEL23-4.23.14 (a, left panel) or αβ IEL16.2 (a, right panel) to triplicate wells of 96-well plate containing 2·5 × 105 B6 responder cells and 10 × 105 irradiated BALB/c stimulator cells in a total volume of 200 μl. Tenfold limiting dilutions of γδ IEL23-4·23·14 (b, left panel) or αβ IEL16·2 (b, right panel) were added to 12 or 24 replicate wells of MLR cultures as described in (a); each symbol represents a replicate well. After 5 days of incubation, 51Cr-labelled P815 targets were added to each well. There were no statistical differences by Student's t-test between any groups except the asterisk indicating P < 0·02 compared to the control group containing no IEL.

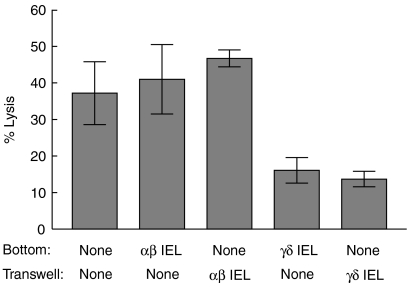

Because so few γδ IEL were required to inhibit the development of CTL activity, it seemed likely that suppression was mediated by secreted molecules rather than by cell-to-cell contact. To test this idea, the ability of IEL to inhibit development of OVA-specific CTL was determined in transwell cultures. γδ IEL inhibited development of OVA-specific CTL equally well when mixed with the responder cells in the bottom of transwell cultures or when separated from the responders in the upper chamber of the transwell cultures (Fig. 9). By contrast, the αβ IEL did not inhibit OVA-specific CTL responses when added to either the upper or lower chamber of the transwell cultures.

Figure 9.

γδ IEL suppression in transwell cultures. Lymph node cells (6 × 106/ml) from B6 mice primed with OVA in CFA were added to 24-well plates. γδ IEL23-4.23.14 or αβ IEL16.2 cells (2 × 102) were added directly to the wells or to inserts that separated the IEL from the responder cells by a membrane with 0·4 μm pores. Cultures were stimulated with 20 μg/ml OVA and assayed for CTL activity with 51Cr-labelled E.G7-OVA targets 5 days later.

Discussion

The experiments in this report demonstrate that long-term lines and clones of γδ T cells (and αβ T cells) can be grown from IEL of the small intestine of the mouse by repeated stimulation with irradiated syngeneic splenic filler cells, Con A and IL-2 or IL-4. Although freshly isolated γδ IEL rapidly undergo apoptosis when incubated ex vivo35 the initial IEL cultures that were stimulated with filler cells, Con A and growth factors routinely proliferated for several weeks and then largely died off, as previously reported by Lefrancois.16 Nevertheless, some lymphoid cells persisted in these cultures and developed into proliferating cell lines after 2–3 months of stimulation. Most of these bulk lines contained γδ T cells and/or αβ T cells. This culture system also gave rise to a few lines that expressed the CD4− CD8− CD3− CD45+ phenotype with or without c-kit. These cells are similar to the c-kit+, lineage marker negative (Lin−) cells isolated from IEL36 and cryptopatches of the small intestine,37 which both gave rise to αβ T and γδ T cells in the small intestine upon adoptive transfer. Similar Lin− CD45+ cells expressing highly immature lymphoid markers, including CD34 and c-kit, were shown to differentiation into both αβ and γδ T cells in reaggregated fetal thymic organ cultures.38 Thus, it appears that our culture system supports the growth of T-cell progenitors and mature TCR+ T cells from IEL. Whether the mature T cells arose in IEL cultures from T-cell progenitors or from a few surviving, mature T cells that escaped cell death cannot be determined from our experiments.

γδ T-cell clones have been previously established from the spleens of normal B6 or BALB/c mice by limiting dilution of purified γδ T cells cultured with syngeneic, splenic filler cells, Con A and IL-2.39 Splenic γδ T cells have also be cloned from TCR α-chain knockout mice by incubation with splenic filler cells and IL-2.34,40 This is the first report, to our knowledge, of the establishment of γδ T-cell clones from the IEL of the small intestine.

All of the γδ IEL lines that have been tested lysed P815 target cells in the presence, but not the absence, of anti-CD3 antibodies, which is similar to the spontaneous activity of freshly isolated IEL.29 By contrast, cloned γδ IEL exhibited only low levels or no lytic activity. Redirected lysis was Ca2+ dependent, suggesting that the perforin pathway is involved. αβ T-cell lines lysed P815 with or without anti-CD3. The mechanism responsible for lysis by these αβ T cells has not yet been characterized. The physiological targets that are recognized by these cytolytic γδ IEL also have not been identified. However, γδ T cells from the skin kill heat-stressed keratinocytes41 which supports the idea that they may recognize damaged or infected epithelial cells.42

All of the many γδ IEL T-cell lines and clones that were tested secreted IL-10 upon stimulation with syngeneic B6 splenic filler cells and Con A, regardless of whether they were raised with IL-2 or IL-4. IL-10 was not secreted by the αβ T cells that were tested. Analysis of IL-10 mRNA expression was consistent with the ELISA data, showing mRNA for IL-10 and variable amounts of mRNA for IL-13. The αβ IEL expressed TNF-α and TNF-β whereas the γδ T cells did not. Both αβ and γδ IEL lines expressed TGF-β1 and MIF mRNA. We do not yet know whether TGF-β1 and MIF are translated into proteins and, if so, whether they are secreted by these IEL lines.

The cytokines produced by the γδ T-cell lines derived from the IEL are distinct from that reported for γδ T-cell lines cultured from the spleen. Splenic γδ T-cell clones grown under conditions similar to the IEL (splenic filler cells, Con A and IL-2) secreted predominantly IFN-γ and TNF, but little or no IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, or IL-10·39 In another study, the CD4− CD8− splenic γδ T-cell clones from TCR α-chain knockout mice expressed IFN-γ and IL-2, whereas splenic CD4+γδ T-cell clones expressed IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 mRNA.34 Most of the splenic γδ T-cell clones from TCR α-chain knockout MRL/Faslpr mice, grown with splenic filler cells and IL-2, secreted IFN-γ and IL-10 but not IL-4, whereas a few secreted IL-4 but not IFN-γ.40 Whether these differences in cytokine patterns among the γ T-cell clones reflect differences in the anatomic sites of origin, differences in the strains of mice, the presence or absence of αβ T cells in the donor mice, or other less obvious differences is not clear. Collectively, these observations suggest that γδ T cells produce various patterns of cytokines that do not necessarily fall into the T helper 1 Th1/Th2 paradigm.

Several γδ IEL clones were tested for immunoregulatory activity in CTL responses. They inhibited the development of alloantigen-specific CTL in primary MLR and OVA-specific CTL in cultures of lymphocytes from mice primed with OVA in CFA. Thus, CTL responses to diverse antigens seem to be inhibited equally well by these γδ IEL suggesting that, if these cells are the γδ T cells required for oral tolerance, their suppressive activity is not specific for exogenous antigens. The inhibitory activity of the γδ T cells was robust and potent (≥10 cells per culture inhibited over 90% of the CTL response). This level of potency is consistent with reports that as few as 103γδ T cells can transfer mucosal tolerance to naïve mice.9 None of the αβ IEL tested were inhibitory at these doses. γδ IEL inhibited development of CTL equally well when mixed with the responder cells or when separated from the responders in a transwell culture system suggesting that inhibition is caused by a soluble mediator.

The γδ IEL T-cell clones described in this report provide a convenient source of cells to study various aspects of their function. However, it is important to remember that they may not accurately reflect certain functional aspects of the in vivo population of T cells because they have been selected for growth in tissue culture. Moreover, it is not clear whether the similarity of these independently derived γδ T-cell lines and clones reflects a limited diversity of the intestinal IEL or whether it was imposed by these culture conditions. Nevertheless, these γδ IEL T-cell lines express cytolytic activity, which is also exhibited by γδ T cells freshly isolated from the IEL of the small intestine. The observation that genes involved in the lytic machinery are expressed with high frequency in freshly isolated γδ and αβ IEL43 is in agreement with the biological activity of these cells. The studies of Shires et al.43 also illustrate some distinctions in mRNA expression between freshly derived cells and our cultured IEL. In freshly isolated cells, MIF and TNF-β were expressed at moderate levels and TGF-β at low levels in both αβ and γδ IEL, whereas IL-10, TNF-α, and other cytokine genes were rarely expressed in either γδ or αβ IEL. Shires et al. concluded, from their extensive analysis of mRNA expressed by fresh IEL, that these cells have an ‘activated but resting’ phenotype. Likewise, the γδ IEL lines and clones described here do not secrete IL-10 unless activated by growth factors or splenic fillers plus Con A.

The soluble mediators secreted by the γδ IEL that inhibited CTL responses have not yet been identified, however, IL-10 is a potential candidate. γδ IEL grown with IL-2 or IL-4 secrete IL-10, which is known to inhibit allogeneic proliferative and cytotoxic T-cell responses generated in MLR.44 However, in preliminary experiments, excess neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody failed to inhibit the suppressive activity of γδ IEL ex vivo. TGF-β mRNA, which is also known to have immunoregulatory activities on CTL responses,45,46 is produced by the γδ IEL. However, it is not likely to be the inhibitory mediator because the non-inhibitory αβ IEL also expressed TGF-β mRNA. However, it is possible that the γδ IEL, but not the αβ IEL, secrete TGF-β because TGF-β mRNA is produced ubiquitously but subject to post-transcriptional47 and post-translational regulation.48αβ and γδ IEL also transcribe MIF, which is known to be a counter-regulator of the anti-inflammatory activities of glucocorticoids.49 Like TGF-β, MIF is also constitutively expressed by most cells and regulated post-transcriptionally.50 It remains to be determined whether MIF is secreted by γδ and/or αβ IEL. Studies are currently in progress to identify the soluble mediator, or mediators, produced by the γδ IEL that are responsible for suppressing CTL responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by research grants CA70372 from the National Cancer Institute and EY13459 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health; a grant from the Foundation for Fighting Blindness; a core grant (P30 EYO06360) from the National Eye Institute; and a gift from Malcolm and Musette Powell.

The authors are very grateful to Drs Rebecca O'Brien and Willi Born (National Jewish Hospital, Denver, CO) for providing reagents and helpful advice concerning the determination of TCR Vγ and Vδ gene usage.

K.C.McK. is the recipient of an NRSA grant F32 EY07079.

Abbreviations

- B6

C57BL/6

- IEL

intraepithelial lymphocytes

- Lin−

lineage negative

- MLR

mixed lymphocyte response

- OVA

ovalbumin

References

- 1.Mowat AM. Oral tolerance and regulation of immunity to dietary antigens. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ke Y, Kapp JA. Oral antigen inhibits priming of CD8+ CTL, CD4+ T cells and antibody responses while activating CD8+ suppressor T cells. J Immunol. 1996;156:916–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiner HL, Friedman A, Miller A, et al. Oral Tolerance: immunologic mechanisms and treatment of animal and human organ-specific autoimmune disease by oral administration of autoantigens. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:809–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.004113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato T, Owen RL. Structure and function of intestinal mucosal epithelium. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. San Diego CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panja A, Mayer L. Diversity and function of antigen-presenting cells in mucosal tissues. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. San Diego CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 177–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland PW, Kambarage DM. Antigen handling by the epithelium and lamina propria macrophages. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 1991;20:577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bland PW, Whiting CV. Antigen processing by isolated rat intestinal villus enterocytes. Immunol. 1989;68:497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayer L, Shlien R. Evidence for function of Ia molecules on gut epithelial cells in man. J Exp Med. 1987;166:1471–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.5.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMenamin C, Pimm C, McKersey M, Holt PG. Regulation of IgE responses to inhaled antigen in mice by antigen-specific γ/δ T cells. Science. 1994;265:1869–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7916481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMenamin C, Oliver J, Girn B, Holt BJ, Kees UR, Thomas WR, Holt PG. Regulation of T cell sensitization at epithelial surfaces in the respiratory track: suppression of IgE responses to inhale antigens by CD3+ TcR α−/β− lymphocytes (putative γ/δ T cells) Immunol. 1991;74:234–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mengel J, Cardillo F, Aroeira LS, Williams O, Russo M, Vaz NM. Anti-γδ T cell antibody blocks the induction and maintenance of oral tolerance to ovalbumin in mice. Immunol Lett. 1995;48:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)02451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonneville M. Recognition of a self major histocompatibility complex TL region product by gamma delta T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5928–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5928. & others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodman T, Lefrancois L. Intraepithelial lymphocytes. Anatomical site, not T cell receptor form, dictates phenotype and function. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1569–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.5.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ke Y, Pearce K, Lake JP, Zeigler HK, Kapp JA. γδ T lymphocytes regulate the Induction and maintenance of oral tolerance. J Immunol. 1997;158:3610–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujihashi K. γδ T cells regulate mucosally induced tolerance in a dose dependent fashion. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1907–16. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.12.1907. & others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lefrancois LB. Basic Aspects of intraepithelial lymphocyte immunobiology. In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J, editors. Handbook of Mucosal Immunology. San Diego CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 287–97. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefrancois L, Lycke N. Isolation of mouse small intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes, Peyer's patch, and lamina propria cells. In: Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1992. pp. 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olive C. Gamma delta T cell receptor variable region usage during the development of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;62:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00081-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore MW, Carbone FR, Bevan MJ. Introduction of soluble protein into the class I pathway of antigen processing and presentation. Cell. 1988;54:777–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Usuba O, Ito M, Bona CA, Moran TM. Antibody-mediated redirected cytolysis against murine melanoma cells in vivo. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6034–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sydora BC. T-cell receptor γ/δ diversity and specificity of intestinal intraepithelial lymphoctyes. analysis of IEL-derived hybridomas. Cell Immunol. 1993;152:305–22. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1293. & others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rocha B, Guy-Grand D, Vassalli P. Extrathymic T cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:235–42. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sasahara T, Tamauchi H, Ikewaki N, Kubota K. Unique properties of a cytotoxic CD4+ CD8+ intraepithelial T-cell line established from the mouse intestinal epithelium. Microbiol Immunol. 1994;38:191–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1994.tb01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefrancois L. Phenotypic complexity of intraepithelial lymphocytes of the small intestine. J Immunol. 1991;147:1746–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nohara O, Kulka M, Dery RE, Wills FL, Hirji NS, Gilchrist M, Befus AD. Regulation of CD8 expression in mast cells by exogenous or endogenous nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2001;167:5935–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pereira P, Gerber D, Huang SY, Tonegawa S. Ontogenic development and tissue distribution of Vgamma1-expressing gamma/delta T lymphocytes in normal mice. 1995. pp. 1921–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Inagaki-Ohara K, Nishimura H, Mitani A, Yoshikai Y. Interleukin-15 preferentially promotes the growth of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes bearing gamma delta T cell receptor in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2885–91. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes DPM, Hayday A, Craft JE, Owen MJ, Crispe IN. T cells with gamma/delta T cell receptors (TCR) of intestinal type are preferentially expanded in TCR-α-deficient lpr mice. 1995. pp. 233–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Guy-Grand D, Malassis-Seris M, Briottet C, Vassalli P. Cytotoxic diiferentiation of mouse gut thymodependent and independent intraepithelial T lymphocytes is induced locally. Correlation between functional assays, presence of perforin and granzyme transcripts, and cytoplasmic granules. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1549–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berke G. The binding and lysis of target cells by cytotoxic lymphocytes. molecular and cellular aspects. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:735–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowin B, Hahne M, Mattmann C, Tschopp J. Cytolytic T-cell cytotoxicity is mediated through perforin and Fas lytic pathways. Nature. 1994;370:650–2. doi: 10.1038/370650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrick DA, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Hseih B, Ferlin WG, Lepper H. Differential production of interferon-γ and interleukin-4 in response to Th1-and Th2-stimulating pathogens by γδ T cells in vivo. Nature. 1995;373:255–7. doi: 10.1038/373255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh B, Schrenzel MD, Mulvania T, Lepper HD, DiMolfetto-Landon L, Ferrick DA. In vivo cytokine production in murine listeriosis. J Immunol. 1996;156:232–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen L, Barber DF, Pao W, Wong FS, Owen MJ, Hayday A. Primary γδ cell clones can be defined phenotypically and functionally as Th1/Th2 cells and illustrate the association of CD4 with Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1965–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viney JL, MacDonald TT. Selective death of T cell receptor γδ intraepithelial lymphocytes by apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2809. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamad M, Whetsell M, Wang J, Klein JR. T cell progenitors in the murine small intestine. Dev Comp Immunol. 1997;21:435–42. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(97)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saito H. Generation of intestinal T cells from progenitors residing in gut cryptopatches. Science. 1998;280:275–8. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.275. & others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woodward J, Jenkinson E. Identification and characterization of lymphoid precursors in the murine intestinal epithelium. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3329–38. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3329::aid-immu3329>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duhindan N, Farley AJ, Humphreys S, Parker C, Rossiter B, Brooks CG. Patterns of lymphokine secretion amongst mouse gamma delta T cell clones. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1704–12. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujii T, Okada M, Craft J. Regulation of T cell-dependent autoantibody production by a gammadelta T cell line derived from lupus-prone mice. Cell Immunol. 2002;217:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Havran WL, Chien YH, Allison JP. Recognition of self antigens by skin-derived T cells with invariant gamma delta antigen receptors. Science. 1991;252:1430–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1828619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Janeway CA, Jones B, Hayday A. Specificity and function of T cells bearing γδ receptor. Immunol Today. 1988;9:73. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shires J, Theodoridis E, Hayday AC. Biological insights into TCRγδ+ and TCRαβ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes provided by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) Immunity. 2001;15:419–34. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bejarano MT, de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams JS, Bigler M, Bacchetta R, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. Interleukin 10 inhibits allogeneic proliferative and cytotoxic T cell responses generated in primary mixed lymphocyte cultures. Int Immunol. 1992;4:1389–97. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fontana A, Frei K, Bodmer S, Hofer E, Schreier MH, Palladino MA, Jr, Zinkernagel RM. Transforming growth factor-β inhibits the generation of cytotoxic T cells in virus-infected mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:3230–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inge TH, Hoover SK, Susskind BM, Barrett SK, Bear HD. Inhibition of tumor-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes responses by transforming growth factor β1. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1386–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim SJ, Romeo D, Yoo YD, Park K. Transforming growth factor-beta: expression in normal and pathological conditions. Horm Res. 1994;42:5–8. doi: 10.1159/000184136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khalil N. TGF-beta: from latent to active. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1255–63. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lue H, Kleemann R, Calandra T, Roger T, Bernhagen J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF): mechanisms of action and role in disease. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:449–60. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fingerle-Rowson G, Koch P, Bikoff R, Lin X, Metz CN, Dhabhar FS, Meinhardt A, Bucala R. Regulation of macrophage migration inhibitory factor expression by glucocorticoids in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]