Abstract

Previous studies have identified a 210 000-molecular weight molecule expressed at a high level on the surface of dendritic cells (DCs) in afferent lymph of cattle and evident on cells with the morphology of DCs in lymphoid tissues. Expression is either absent from other immune cells or is present at a lower level. The molecular weight and cellular distribution suggested that the molecule, called bovine WC6 antigen (workshop cluster), might be an orthologue of human DEC-205 (CD205). To establish whether this was the case, the open reading frame of bovine DEC-205 was amplified, by polymerase chain reaction, from thymic cDNA (accession no. AY264845). The cDNA sequence of bovine DEC-205 had 86% and 78% nucleic acid identity with human and mouse molecules, respectively. COS-7 cells transfected with a plasmid containing the cattle DEC-205 coding region expressed a molecule that stained with WC6-specific monoclonal antibody, showing that ruminant WC6 is an orthologue of DEC-205. Two-colour flow cytometry of mononuclear cells from afferent lymph draining cattle skin, and from blood, confirmed the high level of expression on large cells in lymph that were uniformly DC-LAMP positive and major histocompatibility complex class II positive. Within this DEC-205+ DC-LAMP+ population were subpopulations of cells that expressed the mannose receptor or SIRPα. The observations imply that DCs in afferent lymph are all DEC-205high, but not a uniform population of homogeneous mature DCs.

Introduction

DEC-205 is a type 1 cell-surface protein that belongs to a family of C-type multilectins. Structurally, a cysteine-rich N-terminal domain is followed by a fibronectin type II domain and multiple carbohydrate-recognition domains. A single transmembrane domain is followed by a short cytoplasmic tail.1 Both human and mouse DEC-205 are encoded by single-copy genes, and the protein is encoded from a single cDNA.2 DEC-205 may function as an endocytic receptor involved in the uptake of extracellular antigens. No endogenous ligands have been demonstrated for the molecule, but monoclonal antibody (mAb) specific for DEC-205 is internalized following binding via coated vesicles and then delivered to an endosomal compartment which is active in antigen processing and rich in major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II.1 The internalized antibody or a conjugated antigen are processed and presented efficiently in association with MHC class II.3 It has been suggested that DEC-205 has a different specificity as an antigen-uptake receptor to the macrophage mannose receptor with which it shares structural homology.4

DEC-205 is expressed by a number of different types or subpopulations of dendritic cells (DCs) from various tissues, usually at a higher level than seen on B cells, macrophages or T cells. This, together with the observation that expression is up-regulated during DC maturation, implies an important function for the molecule related to the maturation stage of the DC.4–6 As well as up-regulation during maturation of DCs derived in vitro from cultured monocytes, differences in DEC-205 expression by DCs from lymph nodes correlate with functionally distinct subpopulations. Thus, in mouse lymph nodes DEC-205− DCs that are CD8− CD4− or CD8− CD4+ have been reported as well as DEC-205+ DCs that are CD4− CD8+ or CD4− CD8low.7 In the mouse spleen, DCs that expressed low (80%) or moderate (20%) levels of DEC-205 were reported by Inaba et al.6 Additionally, Kronin et al.8 reported that CD8+ DEC-205+ and CD8− DEC-205− DCs from mouse spleen produced different responses in T cells, and expression of DEC-205 was a good marker of lymphoid-related regulatory type DCs.

In our previous studies of ex vivo DCs, high levels of expression of the antigen, currently called the bovine workshop cluster 6 (WC6) antigen, was used together with size (forward scatter) to identify the DC population present in afferent lymph draining the skin.9 These DCs were not homogeneous and a number of subpopulations were evident that had differing biological properties.10,11 The WC6 antigen was expressed at a lower level by other cells in afferent lymph and by B cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Cells with the morphology of DCs were stained with WC6-specific mAb in the paracortex of lymph nodes and gut mucosa. The molecular weight (MW) was estimated as 210 000.12

Taken together, these observations suggest that the WC6 molecule might be an orthologue of human and mouse DEC-205, which have a similar relative molecular mass (Mr) and cell distribution, although this has not been previously proposed or shown. The objective of this study was to determine whether the ruminant WC6 antigen was an orthologue of DEC-205 (CD205) and to examine the cellular expression of the molecule on ex vivo migrating DCs in afferent lymph draining the skin.

Materials and methods

mAbs

Murine mAbs that are specific for the ruminant WC6 antigen, namely CC98 [immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b)] and IL-A114 (IgG1), were used.12,13 The other mAbs were mouse mAbs that were specific for bovine CD3 (MM1A),14 MHC class II DR (CC108), SIRPα (CD172a, IL-A24),15 CD14 (CCG33),16 surface immunoglobulin M (IgM) (IL-A30),17 surface IgG (IL-A59),18 mannose receptor (3.29B1),19 CD1b (CC14)20 and DC-LAMP (CD208, 104.G4 Coulter). Control mAbs used within the study were AV20 (mouse IgG1), AV29 (mouse IgG2b) and AV37 (mouse IgG2a), which are directed against chicken bursal B cells, chicken CD4+ cells and a chicken spleen cell subset, respectively, all provided by Dr T. F. Davison (Institute for Animal Health, Newbury, UK).

Two-colour staining for flow cytometry was performed essentially as described by Sopp et al.21 Cells were incubated for 10 min with primary mAbs at predetermined optimal concentrations, then washed extensively. Bound mAb was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2 mAb (Southern Biotechnologies, Birmingham, AL). The cells were analysed on a FACSCalibur (Becton-Dickinson, Oxford, UK) and immunofluorescent staining was analysed using fcs express software (De Novo Software, Ontario, Canada).

Cells and tissues

The source of afferent lymph and PBMC has been described in detail previously.11 Pieces of bovine skin and lymph node were embedded in OCT™ compound (Tissue-Tek, Zoeterwoude, Netherlands) and then frozen in isopentane that had been precooled in liquid nitrogen. Sections (5 µm) were cut in a cryostat, transferred to microscope slides and stored at −20° prior to analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were allowed to air dry, fixed in ethanol for 5 min, then 10% normal rabbit serum was added to block non-specific binding. The primary mAbs were added and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature before washing the slides three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The secondary biotinylated mAb (biotinylated anti-mouse IgG; Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) was added for 30 min, and the slides washed three times in PBS prior to the addition of conjugate (ABC solution, Vectastain kit; Vector Laboratories). Following a 30-min incubation, the sections were washed and substrate (NoveRed; Vector Laboratories) was added. Development of colour was observed microscopically. Once optimum staining had been achieved, the slides were washed in water, counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted in DPX.

PCR and cloning of the bovine DEC-205 coding sequence

Messenger RNA was isolated from bovine thymic tissue using oligo-dT Dynabeads, as directed by the manufacturer (Dynal, Wirral, UK). In humans and mice, this primary lymphoid organ contains cells that express high levels of DEC-205 mRNA.1,22 One microgram of oligo(dT)12−18 primer (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) was added to the eluted thymic mRNA, mixed and incubated (70°, 10 min). The mixture was chilled on ice (1 min) and the following components added (note that the concentrations of the components given are those achieved following addition of the reverse transcriptase): 2·5 mm MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 500 µm dNTP (Promega, Southampton, UK), 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) (Invitrogen), 80 U RNAsin (Promega) 20 mm Tris–HCl, pH 8·4, 50 mm KCl. The mixture was incubated (42°, 5 min), 400 U Superscript II (Invitrogen) was added and incubation continued (42°, 50 min) to reverse transcribe the mRNA into cDNA. The mixture was incubated (70°, 15 min), chilled on ice, 4 U RNAse H (Invitrogen) was added and incubation continued (37°, 20 min). Synthesis of first-strand cDNA for use in 3′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using 100 pmol of oligodTadapter primer.

Alignment of the cDNA sequences encoding human (accession number AF011333) and mouse (accession number MM19271) DEC-205 shows that the open-reading frame (ORF) of these genes shares 81% nucleic acid identity with some regions which are entirely conserved. Such a high level of sequence conservation implies functional conservation between these two species that may be shared by the bovine gene. Consensus regions exceeding 17 nucleotides, which were identified from alignments of the human and mouse DEC-205 ORFs, were used to design oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) that were used in PCRs to amplify corresponding regions of the bovine DEC-205 gene from thymic cDNA. Oligonucleotide sequences were also used to design primers nested within the 5′- and 3′ ends to amplify the intervening cDNA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer name | Position of primer 5′ end in reference sequence | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|

| BodecF1 | 1 | ATGAGGACAGGCTGGGTGACCC |

| BodecR2 | 582 | ACACCATGGCCCACTATGATC |

| BodecF2 | 316 | CTGTGGTGGAAATGTGAGC |

| BodecR3 | 1538 | TTCTCCATGTCTCTTCCAGCC |

| BodecF2 | 316 | CTGTGGTGGAAATGTGAGC |

| BodecR2 | 582 | ACACCATGGCCCACTATGATC |

| BodecF2 | 316 | CTGTGGTGGAAATGTGAGC |

| BodecR6 | 3531 | CCAACCAAAGTTGAGTTC |

| BodecF10 | 3297 | ACAGACCTTGTGGAATAC |

| BodecR4 | 5172 | TTAGTCGTGGAAAGAAGG |

| BodecF1 | 1 | ATGAGGACAGGCTGGGTGACCC |

| BodecR15 | 2682 | CCATGGGTCTCGTGAATA |

| BodecF16 | 2153 | AAAGGAGCCCTGATTTAC |

| BodecR4(24) | 5172 | TTAGTCGTGGAAAGAAGGAAGCAT |

| BodecRACE3F1 | 5097 | GTTGGGCTTCTCTTCAGTTCGG |

| Oligodtadapter | polyA tail | GCTCTAGACTAGTCTGCAGAATTCT14 |

Derivation of a transgene encoding bovine DEC-205

To determine whether the WC6 antigen was a bovine DEC-205 orthologue, a single cDNA encoding the complete bovine DEC-205 ORF was required to be cloned into a mammalian expression vector and expressed in COS-7 cells that could be stained with WC6-specific mAb. The strategy used to clone the ORF of the bovine DEC-205 cDNA involved the PCR amplification and cloning of two overlapping cDNAs encoding the 5′- and 3′ ends of the gene, using primers BodecF1 with BodecR15 (5′ portion) and BodecF16 with BodecR4(24) (3′ portion). Products were amplified using pfu turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and ligated into cloning vectors. Amplified product from a PCR using primers BodecF16 and BodecR4 was cloned into pCR Blunt II vector (Invitrogen). The product from the PCR carried out using primers BodecF1 and BodecR15 was T tailed, ligated into the pCR II dual-promoter vector and transformed into TOP10F′Escherichia coli (Invitrogen). The cloned 3′ DEC-205 cDNA was excised using the restriction enzymes AccI, NotI and 1 × React3 buffer (Invitrogen). The AccI restriction site is situated within the overlapping region of the cloned 5′- and 3′ DEC-205 cDNAs. The NotI restriction site is within the multiple cloning site of both vectors. The construct containing the 5′-DEC-205 cDNA was also digested with AccI and NotI to remove the overlap region and produce compatible ends to which the excised 3′ cDNA sequence was ligated, thus producing a construct containing the bovine DEC-205 ORF. Full-length DEC-205 cDNA was excised from the construct using SpeI and NotI restriction enzymes and ligated to compatible ends of the pTarget (Promega) expression vector produced by digestion with NheI and NotI. Ligations were cloned and the plasmid constructs sequenced.

Transfection and staining of COS-7 cells

COS-7 cells were transfected with plasmid pTarget containing cDNA encoding bovine DEC-205 or bovine tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (as a negative control) before being immunostained as described previously.23 Briefly, COS-7 cells were transfected with 6 µg of plasmid DNA using DEAE dextran, then cultured in complete media for 2 days, washed with PBS and fixed and permeabilized with 100% ethanol. Cells were incubated with mAb CC98, or control mAb, at a predetermined optimal concentration for 10 min, then washed extensively. Bound mAb was detected by incubation, for 15 min, with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin coupled to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Following washing, the substrate (AEC) was added for 30–60 min. Development of colour was observed microscopically and, when optimal, the cells were washed in PBS.

Results

Cloning and sequencing cDNAs encoding bovine DEC-205

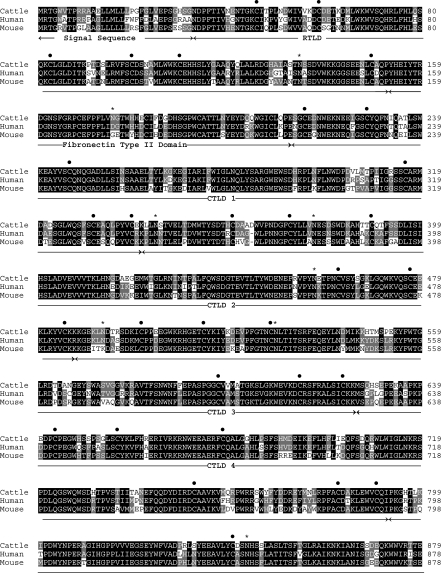

Oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) were used in PCRs to amplify regions of the bovine DEC-205 gene from thymic cDNA. The PCR products were then cloned and sequenced. The nucleic acid sequences of these clones were used to design oligonucleotide primers nested within the 5′- and 3′ ends, to amplify the intervening cDNA. This approach, together with 3′-RACE, produced a number of overlapping clones with contiguous nucleotide sequences, comprising a 5172-bp ORF and a 3′ untranslated region. A search of the EMBL database using fasta software revealed that the ORF of this bovine gene had greatest homology to the human and mouse DEC-205 cDNA sequences, sharing 86% and 78% nucleic acid and 79% and 74% amino acid identity, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Complete amino acid sequence of bovine DEC-205 deduced from the nucleotide sequence of the cloned cDNA. Comparison with human and mouse orthologues shows the following amino acid identities: murine DEC-205, 74%; human DEC-205, 79%. Amino acids comprising protein domains are indicated below the aligned sequences. Conserved cysteine residues involved in stabilization of the ricin-type lectin domain (RTLD) and the calcium-type lectin domain (CTLD), via disulphide bond formation, are indicated by a • above the text. Amino acids involved in DEC-205 internalization (cattle residues 1702–7 and 1713–15) are indicated by  above the text. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated by asterisks above the text. TM, transmembrane domain.

above the text. Potential N-linked glycosylation sites are indicated by asterisks above the text. TM, transmembrane domain.

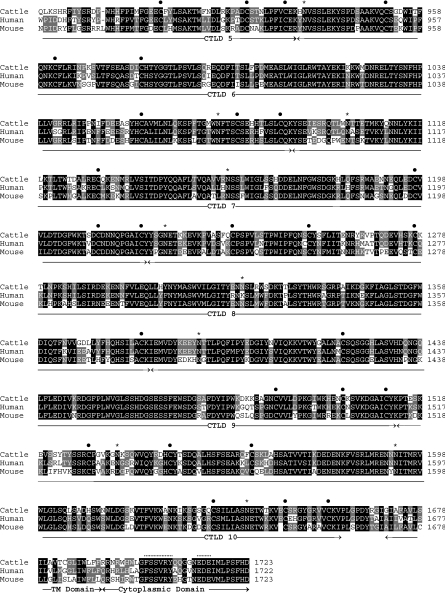

COS-7 cells expressing a transgene encoding bovine DEC-205 are specifically recognized by anti-WC6 mAb

A plasmid clone containing the cDNA encoding bovine DEC-205 in vector pTarget was transfected into COS-7 cells using DEAE dextran. Transfectants were stained with either WC6-specific mAb (CC98) or an isotype-matched control mAb and the staining pattern was analysed by immunohistochemistry. A proportion of cells transfected with the construct encoding the bovine DEC-205 ORF (Fig. 2a), but not cells transfected with a plasmid control encoding TNF-α (Fig. 2b), stained with WC6 mAb. Neither bovine DEC-205 transfectants nor mock transfectants stained with control mAb (data not shown). These data indicate that the WC6 antigen is a bovine orthologue of human DEC-205.

Figure 2.

COS cells transfected with a transgene encoding bovine DEC-205 are recognized by anti-workshop cluster 6 (WC6) monoclonal antibody (mAb). COS-7 cells were transfected with cDNA encoding bovine DEC-205 (a) or bovine tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (b). The COS cells were then immunostained with the WC6 mAb CC98, which stained cells expressing DEC-205, but not TNF-α, indicating that the WC6 antigen is a bovine DEC-205 orthologue.

Cellular expression of bovine DEC-205

To compare the cellular expression of bovine DEC-205 with that of the orthologues in humans and mice, cells or tissues were stained with DEC-205-specific mAb and analysed by flow cytometry or immunohistochemistry.

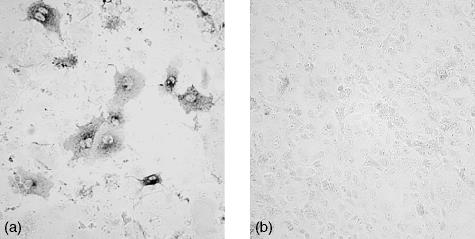

Afferent lymph DCs can be identified by their high forward-scatter properties in flow cytometric analyses. Staining of these DCs in afferent lymph is shown in Fig. 3. Cells with high forward scatter stained more intensely with DEC-205 mAb than cells with lower forward- and side-scatter properties (Fig. 3a,3b). Two-colour flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the DEC-205high-positive cells exclusively expressed DC-LAMP (Fig. 3d). DC-LAMP staining was low, but when cells are gated as in Fig. 3(b) for high forward scatter and DEC-205 staining, all of the DEC-205high cells were clearly stained with the DC-LAMP mAb compared to staining with an isotype-control mAb (Fig. 3j). The DEC-205high cells expressed high levels of MHC class II (Fig. 3g) and they were mostly surface immunoglobulin negative, or stained very weakly for surface immunoglobulin (Fig. 3f), with few surface immunoglobulin-positive cells being evident within the DEC-205high population (Fig. 3f). All of the cells expressing high levels of DEC-205 were CD3 negative (Fig. 3h) and CD14 negative (Fig. 3i). A large proportion of cells expressing moderate levels of DEC-205 expressed CD3, indicating that these were probably T cells. Within the high forward-scatter DEC-205high population (region 1 Fig. 3b), there were subsets of cells expressing SIRPα (Fig. 3k) and the mannose receptor (Fig. 3l).

Figure 3.

Expression of DEC-205 on afferent lymph veiled cells. Afferent lymph cells were obtained by cannulation of pseudoafferent lymphatic vessels that drain the skin of calves, and expression of DEC-205 and other surface molecules, as indicated, was assessed by flow cytometry. All cells in afferent lymph were analysed in panels (a) to (i). Afferent lymph dendritic cells were identified as cells with high forward-scatter (FSc) properties that were DEC-205high, and histograms (j), (k) and (l) are electronically gated on these cells, as indicated in (b). Isotype controls (c) and (e) are for permeabilized and non-permeabilized cells respectively. Only DC-LAMP staining is presented on permeabilized cells. A total of 10 000 gated cells was analysed for each sample.

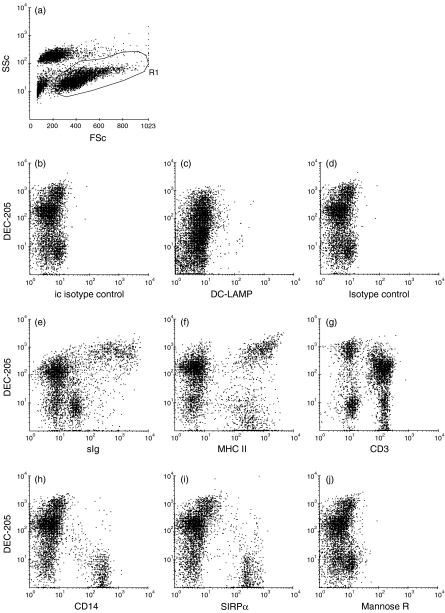

Cells expressing DEC-205 were also evident in PBMC (Fig. 4). Within the mononuclear fraction of lysed blood cells, as indicated in Fig. 4(a), cells expressing moderate and high levels of this molecule were evident (Fig. 4b). None of these cells co-expressed DC-LAMP (Fig. 4c). The majority of DEC-205 highly positive cells expressed MHC class II (Fig. 4f) and stained strongly for surface immmunoglobulin (Fig. 4e), but were SIRPα negative (Fig. 4i) indicating that these are probably B cells. The DEC-205 moderate and high-positive cells were mannose receptor negative (Fig. 4j) and CD14 negative (Fig. 4h). As in afferent lymph, most cells expressing moderate levels of DEC-205 expressed CD3, indicating that these were probably T cells, although some CD3-positive cells were DEC-205 negative (Fig. 4g). CD14+ cells were uniformly DEC-205 negative (Fig. 4i).

Figure 4.

Expression of DEC-205 on peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) populations. PBMC in lysed, heparinized blood were identified by their forward (FSc) and side scatter (SSc), and staining of these cells is shown, electronically gated as in (a). The expression of DEC-205 in relation to other surface molecules, as indicated, was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of 10 000 live-gated cells for each sample. Staining of permeabilized (b,c) and non-permeabilized (d–j) cells. ic, intracellular; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; sIg, surface immunoglobulin.

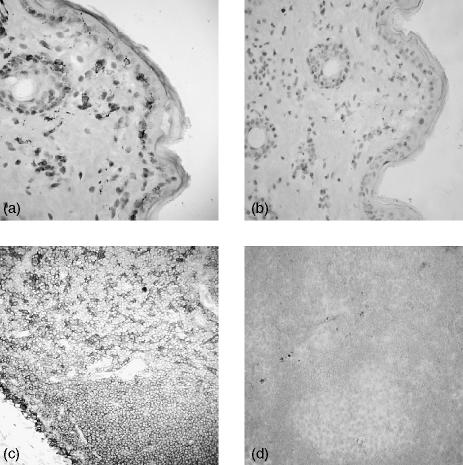

In frozen sections of bovine skin, cells staining strongly with the DEC-205 mAb were evident and dispersed throughout the dermis and epidermis. These cells display a morphology and tissue location that is typical of dermal DCs and Langerhans' cells (Fig. 5a). Within lymph nodes, the DEC-205-positive cells form a network that is evident throughout the T-cell paracortex, indicative of expression of this molecule upon interdigitating DCs (Fig. 5c). Staining was also observed within the B-cell follicles (Fig. 5c). This reflects DEC-205 expression on B cells in the follicles, as shown for B cells in peripheral blood (Fig. 4). No staining was observed with isotype-matched control mAb (Fig. 5b,5d).

Figure 5.

Localization of DEC-205-positive cells in bovine skin and lymph node. Pieces of bovine skin (a, b) and lymph nodes (c, d) were taken postmortem and frozen sections were prepared. Immunohistochemical analyses were performed using DEC-205 monoclonal antibody (mAb) CC98 (a, c) and isotype-control mAb (b, d). The magnification of all samples used a ×2·5 objective.

Discussion

Previous studies of the bovine WC6 antigen have shown it to be a 210 000-MW protein that is expressed at high levels on DCs in afferent lymph which drains the skin of cattle and sheep.9–12,24 As shown here, it is expressed by cells with the morphology of DCs in the dermis and epidermis of the skin, presumed to represent dermal DCs and Langerhans' cells, and cells with the appearance of interdigitating DCs in the paracortex and medulla of lymph nodes. Stained cells with the morphology of DCs are also evident, being scattered in the lamina propria of normal villi in the gut and more extensively in the lamina propria of the domed villi. In the spleen, periarteriolar cells are weakly stained, while cells in the marginal zone and red pulp are strongly labelled. All cortical thymocytes, and the majority of medullary thymocytes, stain.12 Expression in PBMCs is evident on B cells, and at a lower level, or not at all, on CD3+ T cells and monocytes. In the afferent lymph, CD3+ T cells stain less intensely than the DCs. Previous studies with the CC98 mAb showed staining of CD2+ T cells in PBMC, but not WC1+ T-cell receptor (TCR)-γδ+ T cells,12 which can now be interpreted as expression of DEC-205 by most TCR-αβ+ T cells in peripheral blood. B cells in PBMC that were identified as being CD21+ were also shown to stain with the same mAb. WC6 mAb staining of COS-7 cells, transfected with a plasmid encoding bovine DEC-205, confirmed that the WC6 antigen was a bovine orthologue of human DEC-205. Overall, the data indicates that DEC-205 is highly expressed on DCs in many tissues, representing both immature and mature DCs.

The nucleic acid sequence of the bovine DEC-205 ORF indicates a putative mature type 1 transmembrane protein comprising a 32 amino-acid signal sequence, 1640 amino acids in the extracellular region, 22 in the transmembrane domain and 31 in the cytoplasmic tail. The external region of the protein contains 18 potential N-linked glycosylation sites and is composed of 12 protein domains – an N-terminal ricin-type lectin domain (RTLD), a fibronectin-type II domain and 10 calcium-type lectin domains (CTLD). This arrangement of protein domains is characteristic of members of the macrophage mannose receptor or group VI family of animal lectins. The function of some group VI animal lectins is to bind carbohydrate moieties on glycoprotein ligands and internalize them. A number of conserved residues are important for these functions and these are conserved in the bovine DEC-205 protein. Carbohydrate binding by the macrophage mannose receptor is attributed to two different domains that are responsible for binding different classes of oligosaccharide moiety. The N-terminal RTLD binds to the sulphated portion of sulphated acidic glycans. The RTLD is a β-trefoil structure formed by six cysteine residues that pair to form three disulphide bonds. These residues are conserved between human and mouse DEC-20525 and are present in the predicted amino acid sequence of the bovine protein. The macrophage mannose receptor also binds glycans that terminate in mannose, fucose or N-acetylglucosamine via one of the CTLD domains.26 The CTLD structural fold in the group VI animal lectins occurs as long and short forms which are characterized by the presence of either four or six cysteine residues that pair to form two or three disulphide bonds, respectively.27 The 10 CTLDs of bovine DEC-205 are of both long (CTLD 1–4, 6 and 10) and short (CTLD 5 and 7–9) forms; a pattern shared with the human and mouse orthologues. Despite sharing structural homology with the mannose receptor, DEC-205 does not contain the key amino acids critical for calcium co-ordination and sugar binding, and is not predicted to bind oligosaccharide-containing moieties.25,26

No signalling motifs are apparent within the cytoplasmic tail of bovine DEC-205; however, two separate motifs present in the human and mouse orthologues, which are responsible for endocytosis and intracellular trafficking, are conserved in the bovine protein. A tyrosine (Y1707)-containing motif, responsible for internalization through clathrin-coated pits, is proximal to a cluster of three acidic amino acids (EDE) that mediate localization of the protein to the MIIC following its internalization. Enhanced presentation of protein antigens conjugated to DEC-205-specific mAb has been reported which may be related to delivery to this compartment.3

The high level of conservation among the amino acid sequences of cattle, human and mouse DEC-205, particularly within the domains that relate to the endosomal trafficking of the molecule, indicates that its function is conserved across species. Thus, in cattle, antigen directed to DEC-205 would be expected to be delivered to the late MHC II-rich endosomes for processing and presentation to T cells, as demonstrated in the mouse.1,28 As similar levels of DEC-205 are expressed on all bovine afferent lymph dendritic cells (ALDCs), it is unlikely to be the molecular basis for differences in DC subset function noted for subpopulations of these cells.11 However, the delivery of antigen to DCs via DEC-205 in the absence of CD40 ligation can lead to T-cell tolerance and the deletion of clones responding to the presented antigen.29 This observation suggests that the activation/maturation state of the DC is of importance in determining the T-cell response to antigen delivered to the DC via DEC-205.

In mice, DEC-205 was originally described as being abundant on DCs and thymic epithelia and on non-dendritic leucocytes, particularly B cells.30,31 Both DEC-205+ and DEC-205− DC populations have been identified. Henri et al.7 reported three major DC populations, evident in the spleens of mice, that were CD4+ CD8− DEC-205−, CD4− CD8− DEC-205− or CD4− CD8+ DEC-205+. In lymph nodes, these three populations were also evident but there were two additional populations that were CD4− CD8low and either DEC-205moderate or DEC-205high. It is suggested that the DEC-205moderate population is derived from dermal DCs and that the DEC-205high population is derived from Langerhans' cells. Lu et al.32 reported that the propagation of mouse liver non-parenchymal cells with granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) results in myeloid DCs that are CD11c+, but culture in the presence of interleukin (IL)-3 and CD40 ligation results in lymphoid DCs that express DEC-205 rather than CD11c. These cells exhibit a typical DC morphology, migrate into T-cell areas in spleen and lymph nodes after subcutaneous inoculation and stimulate cells, in a mixed leucocyte reaction, which die of apoptosis and regulate T-cell responses.

There is evidence that DEC-205 is up-regulated on DCs after activation. Immature human and mouse DCs generated in vitro from monocytes up-regulate DEC-205 expression and mRNA as they are activated.4,33 In humans, DEC-205 is evident on mature monocyte-derived DCs, but weak or no staining was noted on other PBMC.5 We have noted DEC-205 expression on a subset of DCs derived in vitro by culturing monocytes with GM-CSF and IL-4 (J. C. Hope and C. J. Howard, unpublished observations). Studies in vivo34 reported that in mice the CD8α− CD11bhigh DCs in spleen are activated in vivo subsequent to the inoculation of virus-like particles and, after activation, a proportion of this DC population acquires expression of DEC-205 as well as CD8α. In cattle, DEC-205+ cells are evident in the dermis and epidermis of the skin and the gut epithelium where they would be expected to be relatively immature. In the lymph nodes, DEC-205+ cells, probably mature DCs, are also evident. In afferent lymph that drains the skin of cattle, there is no evidence for populations of DCs expressing different levels of DEC-205.9,11 The majority of the cells in afferent lymph that were DEC-205high+ co-expressed DC-LAMP (CD208). DC-LAMP expression has been associated with the maturation of DC, based largely on in vitro studies.35 However, there are clearly identifiable subpopulations of DCs within the total DEC-205+ population in afferent lymph.10,11 The evidence indicates that these include Langerhans' cells, cells derived from dermal DCs and that there are cells at different stages of maturation within this population.36 Thus, Langerhans' cells can be identified in sheep and bovine skin by staining for acetylcholine esterase (Ach) and, within afferent lymph, Ach-positive cells are evident within the DEC-205+ SIRPα+ subpopulation of ALDC.36,37 Furthermore, within the same DEC-205+ SIRPα+ subpopulation of ALDC, there are cells that are Ach negative, which appear to be present at different stages of maturation, based on differences in levels of expression of the mannose receptor, CD1b and CD21.36 Taken together, these data show that in vivo there are DCs which vary in their state of activation/maturity, that express similar levels of DEC-205+ and that, in comparison to other animal species, where DEC-205 expression appears to be related to maturity or activation of DCs, expression is more uniform. The observations made in relation to expression of DEC-205 on immune cells, other than DCs, is consistent with the view that a broader range of bovine cells express moderate-to-high levels of DEC-205 compared with other animal species. Thus, data shown here and previous observations,12 reinterpreted in the knowledge that the WC6 antigen is a DEC-205 homologue, indicate that high expression is evident on B cells in peripheral blood as well as in follicles in lymph nodes and on CD2+ TCR-αβ+ T cells in blood and afferent lymph, but not on WC1+ TCR-γδ+ T cells.

The general paradigm has been proposed that immature cells at the body surface take up antigen readily by a number of mechanisms, including macropinocytosis, phagocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis. Uptake is down-regulated as DCs mature and migrate to the lymph nodes and, at the same time, the capacity to stimulate T cells is up-regulated.38 At first sight, expression of DEC-205 by immature and, particularly, mature DCs seems to contradict what one might intuitively expect. That is, as a molecule responsible for the uptake of antigen for processing and presentation it should be present on immature DCs to aid environmental sampling prior to maturation of DCs into highly effective stimulators of T cells and poor environmental samplers. However, it has been pointed out from studies of ex vivo ruminant and rodent DCs that the relatively mature cells in afferent lymph still take up antigen effectively as well as being highly effective at stimulating T cells in vitro and priming naïve T cells in vivo.39,40 Although Langerhans' cells cultured for 1–3 days lose their ability to process native protein antigen and acquire the ability to stimulate resting T cells, this is not so for ALDC. Liu & MacPherson41 showed that DCs, derived from the intestine of rats that had undergone mesenteric lymphadenectomy, and which were cultured for 20–72 h in vitro, were as effective in taking up and presenting antigen to immune T cells as freshly isolated ALDC. Thus, mature DCs present in lymph nodes that are derived from ALDC would be expected to take up and present antigen effectively as well as to survive for some days. DEC-205 may be one of the mechanisms by which mature DCs can maintain the capacity to take up antigen for presentation to T cells, thus prolonging this important antigen-presenting function of the cell.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), UK.

Abbreviations

- Ach

acetylcholinesterase

- ALDC

afferent lymph dendritic cell

- CTLD

calcium-type lectin domain

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- DC

dendritic cell

- IL

interleukin

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- ORF

open-reading frame

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- RTLD

ricin-type lectin domain

- WC

workshop cluster.

References

- 1.Jiang W, Swiggard WJ, Heufler C, Peng M, Mirza A, Steinman RM, Nussenzweig MC. The receptor DEC-205 expressed by dendritic cells and thymic epithelial cells is involved in antigen processing. Nature. 1995;375:151–5. doi: 10.1038/375151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kato M, Neil TK, Clark GJ, Morris CM, Sorg RV, Hart DN. cDNA cloning of human DEC-205, a putative antigen-uptake receptor on dendritic cells. Immunogenetics. 1998;47:442–50. doi: 10.1007/s002510050381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawiger D, Inaba K, Dorsett Y, et al. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsivness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:769–79. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato M, Neil TK, Fearnley DB, McLellan AD, Vuckovic S, Hart DN. Expression of multilectin receptors and comparative FITC-dextran uptake by human dendritic cells. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1511–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo M, Gong S, Maric S, Misulovin Z, Pack M, Mahnke K, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. A monoclonal antibody to the DEC-205 endocytosis receptor on human dendritic cells. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:729–38. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inaba K, Swiggard WJ, Inaba M, Meltzer J, Mirza A, Sasagawa T, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Tissue distribution of the DEC-205 protein that is detected by the monoclonal antibody NLDC-145. I. Expression on dendritic cells and other subsets of mouse leukocytes. Cell Immunol. 1995;163:148–56. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henri S, Vremec D, Kamath A, et al. The dendritic cell populations of mouse lymph nodes. J Immunol. 2001;167:741–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kronin V, Wu L, Gong S, Nussenzweig MC, Shortman K. DEC-205 as a marker of dendritic cells with regulatory effects on CD8 T cell responses. Int Immunol. 2000;12:731–5. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.5.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard CJ, Sopp P, Brownlie J, Parsons KR, Kwong LS, Collins RA. Afferent lymph veiled cells stimulate proliferative responses in allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but not γδ TCR+ T cells. Immunology. 1996;88:558–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKeever DJ, MacHugh ND, Goddeeris BM, Awino E, Morrison WI. Bovine afferent lymph veiled cells differ from blood monocytes in phenotype and accessory function. J Immunol. 1991;147:3703–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard CJ, Sopp P, Brownlie J, Kwong LS, Parsons KR, Taylor G. Identification of two distinct populations of dendritic cells in afferent lymph that vary in their ability to stimulate T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:5372–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsons KR, Bembridge G, Sopp P, Howard CJ. Studies of monoclonal antibodies identifying two novel bovine lymphocyte antigen differentiation clusters: workshop clusters (WC) 6 and 7. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;39:187–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(93)90180-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard CJ, Naessens J. Summary of workshop findings for cattle (tables 1 and 2) Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;39:25–47. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(93)90161-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis WC, MacHugh ND, Park YH, Hamilton MJ, Wyatt CR. Identification of a monoclonal antibody reactive with the bovine orthologue of CD3 (BoCD3) Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;39:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(93)90167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooke GP, Parsons KR, Howard CJ. Cloning of two members of the SIRP alpha family of protein tyrosine phosphatase binding proteins in cattle that are expressed on monocytes and a subpopulation of dendritic cells and which mediate binding to CD4 T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199801)28:01<1::AID-IMMU1>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sopp P, Kwong LS, Howard CJ. Identification of bovine CD14. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1996;52:323–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(96)05583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naessens J, Newson J, Williams DJ, Lutje V. Identification of isotypes and allotypes of bovine immunoglobulin M with monoclonal antibodies. Immunology. 1988;63:569–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DJ, Newson J, Naessens J. Quantitation of bovine immunoglobulin isotypes and allotypes using monoclonal antibodies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;24:267–83. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90042-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Werling D, Hope JC, Chaplin P, Collins RA, Taylor G, Howard CJ. Involvement of caveolae in the uptake of respiratory syncytial virus antigen by dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:50–8. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacHugh ND, Bensaid A, Davis WC, Howard CJ, Parsons KR, Jones B, Kaushal A. Characterization of a bovine thymic differentiation antigen analogous to CD1 in the human. Scand J Immunol. 1988;27:541–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1988.tb02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sopp P, Kwong LS, Howard CJ. Cross-reactivity with bovine cells of monoclonal antibodies, submitted to the 6th International Workshop on Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;78:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(00)00262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKay PF, Imami N, Johns M, et al. The gp200-MR6 molecule which is functionally associated with the IL-4 receptor modulates B cell phenotype and is a novel member of the human macrophage mannose receptor family. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4071–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4071::AID-IMMU4071>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tregaskes CA, Young JR. Cloning of chicken lymphocyte marker cDNAs from eukaryotic expression libraries. In: Lefkovits I, editor. Immunology Methods Manual. Vol. 4. Academic Press; 1997. pp. 2297–314. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dutia BM, Ross AJ, Hopkins J. Analysis of the monoclonal antibodies comprising WC6. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;39:193–9. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(93)90181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Chirino AJ, Misulovin Z, Leteux C, Feizi T, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. Crystal structure of the cysteine-rich domain of mannose receptor complexed with a sulfated carbohydrate ligand. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1105–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.7.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullin NP, Hitchen PG, Taylor ME. Mechanism of Ca2+ and monosaccharide binding to a C-type carbohydrate-recognition domain of the macrophage mannose receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5668–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drickamer K. C-type lectin-like domains. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:585–90. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(99)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahnke K, Guo M, Lee S, Sepulveda H, Swain SL, Nussenzweig M, Steinman RM. The dendritic cell receptor for endocytosis, DEC-205, can recycle and enhance antigen presentation via major histocompatibility complex class II-positive lysosomal compartments. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:673–84. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swiggard WJ, Mirza A, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. DEC-205, a 205-kDa protein abundant on mouse dendritic cells and thymic epithelium that is detected by the monoclonal antibody NLDC-145. purification, characterization, and N-terminal amino acid sequence. Cell Immunol. 1995;165:302–11. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Witmer Pack MD, Swiggard WJ, Mirza A, Inaba K, Steinman RM. Tissue distribution of the DEC-205 protein that is detected by the monoclonal antibody NLDC-145. II. Expression in situ in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues. Cell Immunol. 1995;163:157–62. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu L, Bonham CA, Liang X, et al. Liver-derived DEC205+ B220+ CD19− dendritic cells regulate T cell responses. J Immunol. 2001;166:7042–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agger R, Petersen MS, Toldbod HE, Holtz S, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Johnsen BW, Bolund L, Hokland M. Characterization of murine dendritic cells derived from adherent blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:138–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moron G, Rueda P, Casal I, Leclerc C. CD8alpha− CD11b+ dendritic cells present exogenous virus-like particles to CD8+ T cells and subsequently express CD8alpha and CD205 molecules. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1233–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Saint-Vis B, Fugier-Vivier I, Massacrier C, et al. The cytokine profile expressed by human dendritic cells is dependent on cell subtype and mode of activation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1666–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howard CJ, Hope JC. Dendritic cells, implications on function from studies of the afferent lymph veiled cell. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2000;77:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(00)00234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yirrell DL, Reid HW, Norval M, Miller HRP. Qualitative and quantitative changes in ovine afferent lymph draining the site of epidermal orf virus infection. Vet Dermatol. 1991;2:133–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:271–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu LM, MacPherson GG. Antigen acquisition by dendritic cells: intestinal dendritic cells acquire antigen administered orally and can prime naive T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1299–307. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKeever DJ, Awino E, Morrison WI. Afferent lymph veiled cells prime CD4+ T cell responses in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:3057–61. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu LM, MacPherson GG. Antigen processing: cultured lymph-borne dendritic cells can process and present native protein antigens. Immunology. 1995;84:241–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]