Abstract

The kinetics of activation and induction of several effector functions of human natural killer (NK) cells in response to Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) were investigated. Owing to the central role of monocytes/macrophages (MM) in the initiation and maintenance of the immune response to pathogens, two different experimental culture conditions were analysed. In the first, monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) cells from healthy donors were stimulated with autologous MM preinfected with BCG (intracellular BCG). In the second, the NW cells were directly incubated with BCG, which was therefore extracellular. In the presence of MM, CD4+ T lymphocytes were the cell subset mainly expressing the activation marker, CD25, and proliferating with a peak after 7 days of culture. In contrast, in response to extracellular BCG, the peak of the proliferative response was observed after 6 days of stimulation, and CD56+ CD3− cells (NK cells) were the cell subset preferentially involved. Such proliferation of NK cells did not require a prior sensitization to mycobacterial antigens, and appeared to be dependent upon contact between cell populations and bacteria. Following stimulation with extracellular BCG, the majority of interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-producing cells were NK cells, with a peak IFN-γ production at 24–30 hr. Interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-4 were not detectable in NK cells or in CD3+ T lymphocytes at any time tested. IL-12 was not detectable in the culture supernatant of NW cells stimulated with extracellular BCG. Compared to the non-stimulated NW cells, the NW cells incubated for 16–20 hr with BCG induced the highest levels of expression of apoptotic/death marker on the NK-sensitive K562 cell line. BCG also induced expression of the activation marker, CD25, and proliferation, IFN-γ production and cytotoxic activity, on negatively selected CD56+ CD3− cells. Altogether, the results of this study demonstrate that extracellular mycobacteria activate several NK-cell functions and suggest a possible alternative mechanism of NK-cell activation as the first line of defence against mycobacterial infections.

Keywords: BCG, cytokines: interleukins, cytotoxicity, natural killer cells (NK cells), proliferation

Introduction

The importance of cell-mediated immunity in the protection against intracellular pathogens, such as mycobacteria, is well established.1 In addition to antigen-specific T lymphocytes, there is increasing evidence that components of innate or natural immunity, in particular natural killer (NK) cells, are important mediators in the early and non-specific defence against a number of micro-organisms, including mycobacteria.2 Human NK cells represent approximately 10% of all peripheral blood lymphocytes and are characterized phenotypically by the presence of CD16 and/or CD56 surface markers and by the absence of CD3.3 These cells contribute to the innate resistance to infections through several mechanisms, such as secretion of immunoregulatory cytokines, lysis of host cells infected with intracellular pathogens and, in some cases, direct killing of the micro-organism.2 Recently, interest has focused on how cytokines derived from NK cells contribute to host resistance and influence the subsequent development of the antigen-specific T-cell response.4 According to this model, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-12, produced by the infected macrophages, are responsible for triggering a pronounced production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) by NK cells. In turn, this early production of IFN-γ during infection, aside from inducing macrophages to produce antimicrobial nitric oxide, would promote a preferential development of T lymphocytes expressing a T helper 1 (Th1) phenotype which, in several experimental models, strongly correlates with resistance to disease.5 The possible link between innate and specific immunity through the cytokines produced by NK cells may have important implications in the design of new vaccines or adjuvants against tuberculosis. More effective immunoprophylaxis strategies could be obtained by including components that are able to stimulate innate immunity to generate the protective response desired.

Bacterial products or whole bacteria can activate NK cells through mechanisms that differ according to: the species of bacteria; the physical form of the antigen (soluble or particulate); the array of cytokine produced; and the cellular receptor that is stimulated.6–13 The protective role of NK cells against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is still unclear. Recently, it has been reported that although NK cells expand in number and become activated in the lungs of mice infected, by aerosol, with M. tuberculosis, their removal does not substantially alter the expression of host resistance evaluated as bacterial load in the lungs.14 On the contrary, several lines of evidence indicate that NK cells have a role in immunity to mycobacteria. In the mouse model, in vivo depletion of NK cell activity by antibodies leads to enhanced multiplication of M. avium complex,15 and NK cell activity increases in peripheral blood and in pleural effusions of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.16–18In vitro studies showed that freshly purified NK cells or lymphokine-activated killer cells are able to lyse human monocytes infected with live M. bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG)19, M. avium complex20 or M. tuberculosis.21 It has also been demonstrated that NK cells are able to mediate the killing of intracellular mycobacteria. In particular, NK cells stimulated with IL-2 or IL-12 can activate human macrophages to inhibit the growth of M. avium,22,23 while unstimulated NK cells can mediate the killing of intracellular M. tuberculosis H37Rv within the first 24 hr of co-culture with infected macrophages, via granule-independent mechanisms.24

Several aspects of the possible mechanisms and mycobacterial components able to induce activation of such cells in humans have yet to be elucidated. Previous studies conducted in our laboratory have demonstrated that human cell populations enriched in NK and T cells respond to mycobacteria-infected human macrophages with a predominant proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes.25 Preliminary studies have also demonstrated that when the same cell populations are stimulated with extracellular mycobacteria, in cultures depleted of macrophages, CD3− CD16+ cells (NK cells) are primarily involved in the proliferative response.25 The present study was undertaken to further investigate the possible interaction of BCG with human NK cells and to determine how such an interaction affects the activation, proliferation, cytokine production and cytotoxic activity of NK cells. The results obtained demonstrate an in vitro direct mycobacterial-mediated activation of several NK cell functions with no apparent involvement of NK-stimulating cytokine production by antigen-presenting or accessory cells.

Materials and methods

Mycobacterial cultures and antigen preparations

BCG (Pasteur Merieux, Lyon, France) was grown in rolling bottles in modified Sauton's medium enriched with 0·5% sodium pyruvate and 0·5% glucose.26 Bacteria were harvested in the logarithmic growth phase, washed by centrifugation and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 5 × 107 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml. Aliquots were stored frozen at −70° until use. For each experiment, an aliquot was thawed and inoculated into liquid growth medium. After 8 days of rolling culture at 37°, bacteria were harvested, washed twice in PBS and vortexed for 20 min with glass beads to dissolve clumps. The bacterial suspension was incubated in the dark for 20 min at 1 g to allow sedimentation of residual clumps. The density of the suspension was determined spectrophotometrically at 600 nm. After centrifugation, the bacterial pellet was diluted in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine (Hyclone Europe Ltd, Cramlington, UK) and 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum to achieve ≈1 × 106 CFU/ml. Killed BCG was prepared by incubating the bacterial suspension at 80° for 1 hr. The infectious dose and the efficiency of the killing procedure were assessed by plating 10-fold dilutions of the bacterial suspension, in duplicate, on Middlebrook 7H11 agar enriched with oleic acid, albumin, dextrose and catalase (Becton-Dickinson Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, MD).

Subjects

Heparinized venous blood was obtained from healthy volunteers, 25–40 years of age. Eight subjects had been vaccinated with BCG at least 3 years before the donation. Seven subjects had no history of previous BCG vaccination and exhibited a negative skin-test reaction to purified protein derivative of M. tuberculosis (PPD). For isolation of NK cells, buffy coats were obtained from six healthy blood donors attending the Transfusion Centre of the University Hospital of Pisa. In this case, the skin-test reactivity to PPD of the subjects was not known. Informed consent was obtained and the protocol was approved by the local ethics committee.

Cell populations

Heparinized venous blood or buffy coats were diluted in PBS containing 10% sodium citrate (v/v) and layered on a standard density gradient (Lymphoprep; Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada). After centrifugation (160 g, 20 min, room temperature), supernatants were removed, without disturbing the lymphocyte layer at the interface, to eliminate platelets. The gradient was further centrifuged (800 g, 20 min), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were collected from the interface. Cells were washed three times with PBS containing 0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (w/v). An aliquot of PBMCs was resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine and then seeded in 48-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA) at a density of 1 × 106 cells/cm2. Monocyte monolayers were obtained after 1 hr of incubation at 37° in humidified air containing 5% CO2, by removing non-adherent cells by gentle repetitive washes with prewarmed RPMI-1640. Cell populations depleted of monocytes and B cells were obtained by passing PBMCs, resuspended in RPMI-1640 containing 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), over a nylon wool column (Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany), according to standard procedures. Effluent cells were washed and resuspended in complete medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum) at a concentration of 1·5–2 × 106 cells/ml. Following immunostaining with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against cell-surface markers (see below), a phenotypic analysis of the monocyte-depleted nylon wool effluent (NW) cells was performed by flow cytometry (FACSort; Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). On average, the effluent population consisted of: 79·5 ± 2·2% CD3+, 47·8 ± 2·4% CD4+, 28·9 ± 2·6% CD8+, 4·9 ± 0·8%γδ+ T cells, 15·0 ± 1·8% CD56+ CD3− NK cells, 0·5 ± 0·09% CD20+ B cells, and 1·4 ± 0·2% CD14+ CD3− monocytes.

Isolation of human NK cells

The population of CD56+ NK cells was purified by removing CD3+ cells from NW cells using Dynabeads M-450 CD3 (n°111·13; Dynal, Oslo, Norway) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly CD3 mAb-coupled magnetic beads were washed with PBS containing 0·1% BSA (w/v) and added to NW cells at a ratio of at least 4 : 1 (beads:CD3+ cells) for 30 min on a rotating platform (Dynal) at 4°. CD3+ cells were then removed using a Dynal magnetic particle separator. Where necessary, the treatment included an additional incubation with CD14 (monocytes) and CD15 (monocytes/granulocytes) mAb-coupled magnetic beads for further purification of CD56+ cells. Two-colour flow cytometric (FACSort) analysis, using CD3-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and CD56-phycoerythrin (PE) mAbs (Becton Dickinson), confirmed that the resulting cell populations consistently contained >90% CD56+ CD3− NK cells (Fig. 4a). Negatively selected NK cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated autologous serum, and seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 0·8−1 × 106 NK cells/cm2.

Infection of monocytes and the stimulation assay

Monocytes were infected with live BCG at a bacteria : cell ratio of 1 : 5. Phagocytosis was allowed to occur for 3 hr at 37° in humidified air containing 5% CO2. Monocytes were then washed three times with PBS to remove non-ingested bacteria, and 1·5−2 × 106 autologous NW cells were added to each well. Alternatively, the adherence and infection steps were omitted and 1·5−2 × 106 NW cells or 0·8−1 × 106 NK cells were directly cultured with extracellular live BCG [4·8 ± 0·8 × 105 CFU per well (48-well plate), mean value ± standard error of the mean (SEM)]. Phytohaemagglutinin (PHA) (5 µg/ml), or phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (25 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (1 µg/ml), were used as positive controls for cell reactivity (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Antigen-free cultures (RPMI) were established as negative controls.

Proliferation assay and identification of cell subsets responding to BCG

Proliferative responses of the NW- or NK-cell isolated populations, following stimulation with BCG, were assessed by flow cytometric measurement of 5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich) uptake, as previously described.25 Briefly, 16 hr before culture termination, BrdU was added to the wells at a final concentration of 30 µg/ml. Non-adherent cells were collected, washed and resuspended in PBS. Each cell suspension was divided into identical aliquots and each was stained with a PE-conjugated mAb directed against different phenotypic surface markers (see below). Cells were fixed overnight in PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 0·01% Tween-20. After one wash, cells were resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing Ca2+ and Mg2+ and 50 Kunitz units/ml bovine pancreatic DNAse I (Sigma-Aldrich), and DNA digestion was continued for 30 min at 37°. After washing, the cells were resuspended in 150 µl of PBS containing 10% BSA and 0·5% Tween-20, and stained with an FITC-labelled BrdU mAb (Becton Dickinson). After incubation for 45 min at room temperature, cells were washed, resuspended in PBS and analysed by flow cytometry.

Twenty-thousand events were acquired ungated for each cell-surface marker in a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For analyses, viable cells were selected by a widely set gate on a two-parameter plot of side-scatter versus forward-angle scatter, to include small as well as large cells, and kept constant for each condition. CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson) was used for computer-assisted analyses. The percentage of FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU+ cells gave the total proportion of proliferating cells, while the percentage of double-positive (FITC–anti-BrdU+/PE–antisurface marker+) cells represented the proportion of each distinct proliferating cell subset in relation to the gated population. Finally, the percentage of each cell subset in the proliferating population was calculated as follows: [(FITC–anti-BrdU+/PE–antisurface marker+ ÷ FITC–anti-BrdU+) × 100].

The absolute number of different proliferating cell subsets in response to BCG-infected monocytes/macrophages (MM), or to extracellular BCG, was assessed as previously described.27

Intracellular analysis of cytokine production

Intracellular cytokine staining was used to determine IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 production at the single-cell level, as previously described,28 with minor modifications. Briefly, blocking of cytokine secretion and consequent intracellular accumulation were achieved by treatment with brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich), which was added to stimulated or unstimulated NW or NK cells at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml. After 4 hr of incubation, cells were harvested and stained with mAbs specific for different surface markers (see below). After washing, cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS for 5 min at 37°. Fixation was stopped by adding cold PBS, containing 1% BSA, followed by centrifugation (500 g, 10 min). Cells were permeabilized with 1 ml of 0·1% (w/v) saponin (Sigma-Aldrich), in PBS containing 1% BSA, for 10 min at room temperature. After centrifugation (1 min, 700 g), FITC-conjugated anti-IFN-γ or IL-2, or PE-conjugated anti-IL-4 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) were added to the permeabilized cells and allowed to bind for 30 min at room temperature. After washing in PBS containing 0·1% (w/v) saponin and 1% BSA, samples were acquired by flow cytometry, and data were analysed using cellquest software (Becton Dickinson). Negative control samples were incubated with irrelevant isotype-matched mAbs in parallel with all experimental samples. The percentage of each cell subset in the IFN-γ-producing population was calculated as follows: [(FITC–anti-IFN-γ+/PE–antisurface marker+ ÷ FITC-anti-IFN-γ+) × 100].

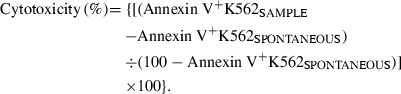

Cytotoxicity assay

Induction of apoptosis/death markers on the NK-sensitive K562 cell line (target) incubated with BCG-stimulated NW cells or isolated NK cells (effectors), was investigated by flow cytometry, as previously described.29 To achieve this, NW or NK cells, stimulated in vitro for 16–20 hr with live BCG, or unstimulated (incubated in RPMI), were added, at different effector : target ratios, to K562 cells prelabelled with the lipophilic dye, PKH26 (Sigma-Aldrich). After 4 hr of incubation, cells were stained with FITC-labelled annexin-V and analysed by flow cytometry. Data analysis was performed first by gating on PKH26-positive target cells (side-scatter versus log red-fluorescence [FL2] plot) followed by the analysis of annexin-V+ cells. The percentage of cytotoxicity in the PKH26-gated cell population was calculated by subtracting non-specific annexin-V+ target cells, measured in appropriate controls without effector cells, according to the formula:

|

Determination of extracellular IFN-γ and IL-12

The levels of IFN-γ and IL-12 present in the culture supernatant were quantified by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (ELISA Cytokine kit; Euroclone Ltd, Paignton-Devon, UK), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Supernatants were collected at different time-points from cultures stimulated with BCG or from unstimulated (RPMI) cultures, and stored in aliquots at −70° until use. Recombinant IFN-γ and IL-12 were used as standards in the corresponding assays. The detection limits for the assays were 6 pg/ml for IL-12 and 12 pg/ml for IFN-γ.

Immunofluorescence staining for surface markers

Cells (1−5 × 105) were resuspended in PBS and incubated with saturating amounts of antibodies for 30 min at 4°. Two- or three-colour immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described.30 The following FITC- or PE-conjugated mAbs were used for staining: anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-CD14, anti-CD15, anti-CD20, anti-CD25 (Ancell Corp., Bayport, MN), anti-CD8, anti-CD16, anti-CD56, anti-T-cell receptor (TCR)-γδ-1 (11F2, recognizing all γδ+ T cells), anti-TCR-αβ, anti-CD3 (peridinin chlorophyll protein [PerCP]-conjugated), and isotype-matched PerCP-, PE- and FITC-conjugated mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) as negative controls (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of the data was determined by the Student's t-test. A P-value of < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Depletion of MM from cell culture promotes a preferential proliferation of NK cells upon stimulation with live BCG

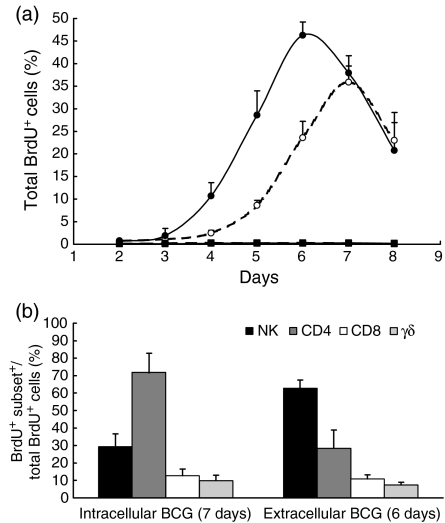

The kinetics of the proliferative response of PBMCs, depleted in monocytes and B cells and enriched in T and NK cells (NW cells), from five healthy BCG-vaccinated donors, was analysed. Owing to the central role of MM in both natural and acquired immune responses to mycobacteria, two different cell-culture conditions were analysed. In the first, NW cells were stimulated with autologous monocytes preinfected with BCG at a bacteria : cell ratio ensuring preferential intracellular growth of the bacteria. In the second, the macrophage-infection step was omitted and the NW cells were incubated directly with live BCG that were therefore mainly localized in the extracellular space. Proliferation was evaluated by flow cytometric determination of BrdU incorporated into the nucleus of the dividing cells. As depicted in Fig. 1(a), a marked proliferative response was observed in response to both intracellular and extracellular BCG, but with slightly different kinetics. Under both conditions the percentage of BrdU+ cells showed a progressive increase, starting 3 to 4 days after in vitro stimulation. However, in the presence of MM as antigen-presenting cells, the peak of the proliferative response was reached after 7 days of stimulation, while in the MM-depleted cultures such a peak was reached by 6 days. At the peak time the total percentage of BrdU+ cells was similar in the two culture conditions analysed (35·9% ± 3·6 in the presence of MM versus 46·3% ± 2·9 in MM depleted-cultures; P > 0·05, Student's t-test for paired samples). The percentage of BrdU+ cells in antigen-free cultures (RPMI) was less than 1% at all time-points tested.

Figure 1.

Proliferative response of monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) cells upon in vitro stimulation with bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). (a) The kinetics of proliferation was evaluated by flow cytometric determination of 5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine (BrdU) incorporated into the nucleus of the dividing cells upon stimulation with intracellular (○) or extracellular (•) BCG. Antigen-free cultures with (□) or without (▪) macrophages. (b) The contribution of different cell subsets to the total proliferative response at the peak times. Mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of results from five subjects are illustrated.

The contribution of different cell subsets to the total proliferative response was assessed at the peak time of proliferation by two/three-colour flow cytometric determination of BrdU incorporated into DNA, and simultaneous identification of cell-surface markers. In the presence of MM, CD4+ T lymphocytes represented the prevalent proliferating cell subset, while stimulation of NW cells with extracellular live BCG induced a marked proliferation of CD56+ CD3− cells (NK cells), which represented 63% ± 4·6 of the proliferating cells (Fig. 1b).

Proliferative responses of distinct cell subsets responding to BCG-infected macrophages or to extracellular BCG were also evaluated as absolute cell counts and confirmed the results obtained based on relative cell counts (data not shown).

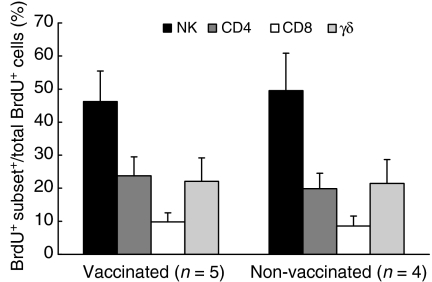

Proliferation of NK cells does not require a prior sensitization to mycobacterial antigens

The composition of the proliferating subsets responding to extracellular BCG in the MM-depleted cultures, was compared between BCG-vaccinated (n = 5) and non-vaccinated (n = 4) healthy donors. In both groups of subjects, NK cells represented the predominant cell population proliferating in response to extracellular BCG (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Composition of proliferating cells, after 6 days of in vitro stimulation of monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) cells with extracellular bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG), in BCG-vaccinated and non-vaccinated donors. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

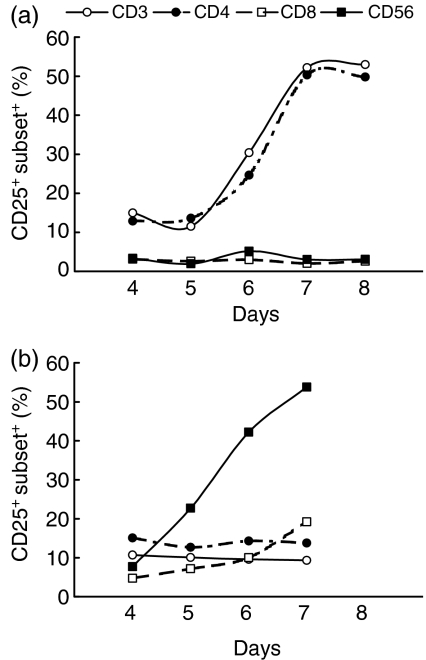

Stimulation of NW cells by extracellular BCG induces expression of the activation marker, CD25, preferentially on NK cells

Expression of the IL-2 receptor (responding to intracellular or extracellular BCG) on NW cells, was investigated using a mAb directed against the CD25 cell-surface molecule. As illustrated in Fig. 3, for a representative donor, stimulation of NW cells with autologous BCG-infected MM resulted in a marked expression of CD25 almost exclusively on CD3+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 3a). In contrast, in response to extracellular BCG, the cell population preferentially activated was CD3− and CD56+ (Fig. 3b). In unstimulated cultures (RPMI), CD56+ or CD3+ cells barely expressed surface CD25 (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kinetics of interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor (CD25) expression on monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) cells responding to (a) intracellular or (b) extracellular bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). Upon in vitro stimulation with BCG, NW cells were stained for phenotypic markers and activation marker CD25, and analysed by two- or three-colour flow cytometry. Results obtained from a representative donor are depicted. CD3 (○), CD4 (•), CD8 (□), CD56 (▪).

Proliferation of NW cells in response to extracellular BCG requires contact between bacteria and cell populations

In order to assess whether proliferation of NW cells in response to extracellular BCG depended on contact between bacteria and cells, or was caused by soluble factors produced by living mycobacteria, a membrane with a 0·2-µm pore-size was interposed in the well between bacteria (upper chamber) and cell populations (lower chamber). While NW cells that were co-cultured directly with extracellular bacteria (both in the lower chamber) underwent high levels of proliferation, the separation of bacteria and cells in the dual-chamber culture system abrogated proliferation almost completely (percentage of BrdU+ cells in the well: 40·6 ± 4·2% versus 3·6 ± 0·8%; P < 0·01, n = 4, Student's t-test for paired samples) (data not shown).

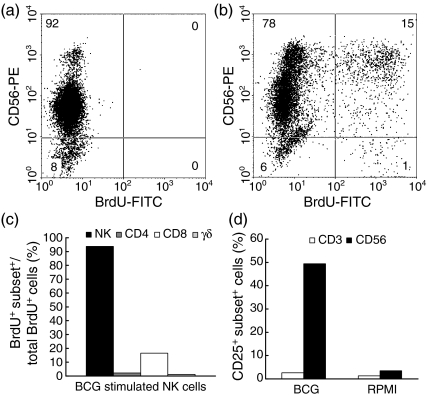

NK cells isolated by negative selection proliferate and express CD25 after stimulation with BCG

The ability of BCG to induce proliferation of isolated NK cells, independently of the presence of T cells in the culture, was evaluated after immunomagnetic depletion of CD3+ lymphocytes and residual CD14+ and CD15+ cells from the NW cells. Negatively selected NK cells represented > 90% of cells in the culture (Fig. 4a). Contaminant CD4+ and TCR γδ+ lymphocytes were, altogether, less than 5%, while the majority of CD8+ cells (> 95%) were also CD56+; CD14+ cells were less than 1%. As depicted, in Fig. 4, for a representative experiment, after 6 days of in vitro stimulation the proliferation of NK cells was observed following two-colour immunostaining with an FITC-conjugated anti-BrdU mAb and PE-conjugated anti-CD56 (Fig. 4b). More than 90% of the proliferating cells expressed the CD56 marker; ≈20% of the BrdU+ cells were CD8+; proliferation of CD4+ and TCR-γδ+ cells was almost undetectable (Fig. 4c). No proliferation was observed in cultures without bacterial cells (Fig. 4a). Isolated NK cells expressed the activation marker, CD25, upon stimulation with extracellular BCG; as depicted in Fig. 4(d), 49·4% of the cells were CD56+ CD25+, indicating that NK cells had been activated by stimulation with BCG in the absence of T cells.

Figure 4.

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) induces isolated natural killer (NK) cells to proliferate and express the activation marker CD25. (a) Unstimulated NK cells, (b) BCG-stimulated NK cells, (c) composition of proliferating cells, (d) percentage of CD25-expressing cells. RPMI, antigen-free cultures. Results obtained from a representative donor are depicted.

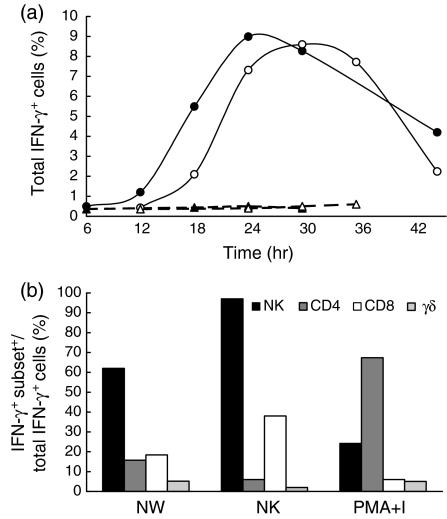

Extracellular BCG induces IFN-γ production by NK cells

The kinetics of production of immunoregulatory cytokines was analysed at the single-cell level following stimulation of NW cells with extracellular BCG. At each time-point analysed, the production of intracytoplasmic IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-4 was assessed by flow cytometry. As depicted in Fig. 5, for a representative experiment, the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells progressively increased in response to BCG, starting 12 hr after in vitro stimulation. In most of the donors tested, the peak of IFN-γ production by NW cells was observed after 24 hr of stimulation (Fig. 5a). The percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells in antigen-free cultures (RPMI) was <1% at all time-points tested. NW cells stimulated with PMA + ionomycin produced IFN-γ with a faster kinetic. In this case, 25% of the cells expressed intracellular IFN-γ after 6 hr of culture (data not shown). In NK cells or in CD3+ T lymphocytes stimulated with extracellular BCG, no detectable intracytoplasmic levels of IL-2 and IL-4 were found at any time-point tested, while in NW cells stimulated with PMA + ionomycin, IL-2 and low (but measurable) IL-4 expression were observed after 6–8 hr of stimulation (21·7 ± 8·8% and 2·5 ± 0·6%, respectively, n = 5) (data not shown). The proportion of each cell subset within the IFN-γ+ population was analysed, at the peak time of production, by two- or three-colour flow cytometric determination of intracytoplasmic IFN-γ and simultaneous analysis of cell-surface markers. CD56+ CD3− cells were the predominant cell subset involved in IFN-γ production (Fig. 5b). In contrast, when NW cells from the same donor were stimulated with PMA + ionomycin, ≈70% of the cells expressing intracellular IFN-γ were CD4+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 5b). Similarly to that observed with NW cells, extracellular BCG was able to induce isolated NK cells to produce IFN-γ, peaking 24–30 hr after in vitro stimulation (Fig. 5a,5b).

Figure 5.

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) and natural killer (NK) cells upon in vitro stimulation with extracellular bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). (a) Kinetics of IFN-γ production by BCG-stimulated NW cells (•), BCG-stimulated NK cells (○), unstimulated NW cells (▴) and unstimulated NK cells (▵). (b) Composition of IFN-γ-producing cells at peak times. Cells were stained for surface markers and for intracytoplasmic IFN-γ and analysed by two-colour flow cytometry. The results obtained from a representative donor are shown. PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate; I, ionomycin.

The amount of IFN-γ released into the culture supernatant by NW cells and isolated NK cells stimulated with BCG was measured, at the time of peak production, by ELISA, and was found to be 20·8 ng/ml and 13·6 ng/ml, respectively.

To explore whether the IFN-γ production by NK cells was induced by IL-12 released from MM contaminating the NW population, IL-12 was measured at 12-hr intervals (from 12 hr to 144 hr) in the culture supernatants of NW cells stimulated in vitro with extracellular BCG. No detectable levels of IL-12 were observed at any time-point tested (data not shown).

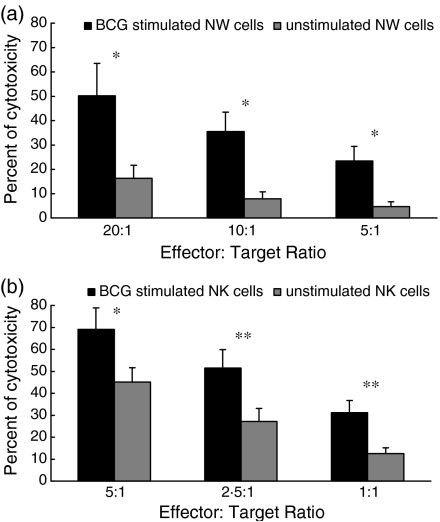

Extracellular BCG-stimulated NK cells induce an apoptosis/death marker on the NK-sensitive K562 cell line

Induction of apoptotic/death markers on the NK-sensitive K562 cell line incubated with BCG-stimulated NW cells, or isolated NK cells, was investigated by flow cytometry. Cells stimulated in vitro for 16–20 hr with extracellular BCG, or unstimulated cells (incubated in RPMI), were added, at different effector : target ratios, to exponentially growing K562 cells prelabelled with the lipophilic dye, PKH26. After 4 hr of incubation, K562 cells were stained with FITC-labelled annexin-V and analysed by flow cytometry. Figure 6 depicts the results obtained as mean values of five independent experiments with different donors. At different effector : target ratios, the percentage cytotoxicity was higher after incubation of K562 cells with NW or NK cells stimulated with BCG (Fig. 6a,6b, respectively) than after incubation with the unstimulated NW or NK cells (Student's t-test for paired samples, P < 0·01–0·05).

Figure 6.

Effect of bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) stimulation on the cytotoxicity of monocyte-depleted nylon wool non-adherent (NW) and natural killer (NK) cells. (a) NW or (b) NK cells stimulated for 16–20 hr with BCG, or unstimulated (RPMI), were added, at various effector : target ratios, to K562 target cells prelabelled with PKH26. After 4 hr of incubation, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labelled annexin-V to detect apoptotic/dead cells. The mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of results from (a) five or (b) six subjects is illustrated for each effector : target ratio. *P < 0·05; **P < 0·01; Student's t-test for paired samples.

Discussion

The role of NK cells during infections with intracellular bacteria has recently attracted considerable interest as there is strong evidence that the complete elimination of the bacterial pathogen from the host requires that the innate cellular system and the specific T-cell response interact efficiently.31

In the present study, activation and induction of several NK-cell functions in response to BCG was demonstrated. First, proliferation of CD56+ CD3− NK cells and different T-cell subsets was investigated in response to live BCG by using a flow cytometric technique that allows identification of distinct proliferating subsets within mixed cell populations. Interestingly, a preferential proliferation of NK cells was only observed when extracellular BCG was used as a stimulant of NW cells under conditions of macrophage depletion. Such results suggest that NK cells may proliferate when the phagocytosis step does not prevent the free interaction between mycobacteria and cells. In agreement with the aspecific nature of the innate cell response, the NK cells were the prevalent cell subset proliferating in response to extracellular BCG, independently from a previous sensitization with mycobacterial antigens. Furthermore, NK cell proliferation was dependent on bacteria–cell contact as it was almost completely abrogated when bacteria and cells were separated with a 0·2-µm pore-size membrane. Proliferation of CD56+ cells did not seem to totally depend on the presence of T cells in the culture, as negatively selected NK cells also underwent substantial BCG-induced proliferative responses. In a previous study, which was undertaken to identify human cell subsets responding to different subcellular fractions of BCG, we demonstrated that a cell-wall-enriched antigen preparation was particularly effective in triggering the proliferation of NK cells compared to other antigenic fractions, respectively, enriched in cytosolic, membrane or secreted proteins.32 Altogether, the results presented herein, and in previous studies,25,32 indicate that the proliferation of NK cells in response to extracellular BCG is not caused by soluble factors released by bacteria, but rather by a possible direct interaction between NK cells and mycobacteria via component(s) present and/or expressed on the bacterial surface.

Although NK cells were initially characterized for their marked lytic functions against a variety of cell targets, the contribution of NK-derived cytokines to host immunity has been remarkably highlighted during recent years.4,5 In the present study, we assessed the production of intracytoplasmatic cytokines by NW cells upon stimulation with extracellular BCG, at the single-cell level, by flow cytometry. The results obtained showed a marked production of IFN-γ by NK cells at early time-points after stimulation, in the absence of detectable intracytoplasmic IL-2 and IL-4 in T lymphocytes present in the culture and of IL-12 in the culture supernatants. IFN-γ production was also elicited by BCG on isolated NK cells obtained by negative selection. Thus, production of IFN-γ by NK cells does not seem to be the result of an IL-2-mediated activation of such cells or because of IL-12 secretion by eventual contaminating macrophages, but rather is consistent with the direct stimulation of IFN-γ production by bacteria. It is generally agreed that during the innate response to infections, monocyte-derived cytokines (monokines) stimulate NK cells to produce immunoregulatory cytokines that are important to the host early defence.4 Herein we provide evidence that a direct interaction between extracellular mycobacteria and NK cells may also represent a stimulus that is sufficient to induce cytokine secretion by such cells. Many pathogens, including mycobacteria, have developed the ability to modulate cytokine production by phagocytic cells of the innate immune system, for example inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and/or promoting that of anti-inflammatory cytokines.33 A direct activation of NK cell functions could represent a bypass mechanism of generation of activated NK cells, particularly important in the defence against those pathogens that, like mycobacteria, may down-regulate the production of IFN-γ-inducing cytokines by phagocytic cells.34 Interestingly, by using an in vitro model of infection of human monocytes with M. tuberculosis H37Rv, ensuring a predominant intracellular growth of the bacteria, Brill and co-workers were unable to demonstrate IFN-γ production by purified NK cells co-cultured with infected monocytes for 24 hr, while they detected only negligible amounts at 96 hr postinfection. In the same study, pg levels of IFN-γ were detected in the supernatants only at 96 hr of co-culture with peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL).24 Such results further support the hypothesis that an NK cell–bacteria contact is required to induce optimal IFN-γ production. Secretion of IFN-γ by NK cells upon exposure to whole Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria, or purified lipopolysaccharide, has been described in previous studies.8,9,11,35 Yoshihara and co-workers reported IFN-γ production by CD16+ NK cells when stimulated with Staphylococcus aureus, but not by T cells, even when macrophages were added to the cultures.35 Cell-free supernatants obtained from PBL cultured for 18 hr with high numbers of shigellae or salmonellae were demonstrated to contain significant levels of IFN activity (both IFN-γ and IFN-α), but no IL-2 activity could be detected in the same supernatants.8 Such IFN production depended upon the presence of CD16+ cells at the culture initiation and did not stem from cellular invasion of PBL, as bacterial cells were pretreated with kanamycin, a treatment that rapidly destroys the invasive activity of both shigellae and salmonellae.8 The ability of IFN-γ to activate the mycobactericidal activity of human macrophages is still controversial. Following stimulation with IFN-γ, monocytes from different donors exhibited a variable capacity to affect the intracellular survival of mycobacteria, ranging from marked inhibition to marked enhancement of growth.36 Early production of IFN-γ by human NK cells, following interaction with mycobacteria, could thus mainly be involved in addressing the nature of the subsequent antigen-specific T-cell response versus a Th1 phenotype.

In order to assess whether extracellular BCG was also able to induce cytotoxic effector functions of NK cells, in the present study, expression of apoptotic/death markers on the NK-sensitive K562 cell line was assessed by flow cytometry, after incubation with NW or isolated NK cells stimulated with BCG. Incubation of NW or NK cells with BCG significantly augmented the cytotoxic capacity of these cells against NK-cell sensitive targets. Such results are in agreement with previous studies investigating the bacterial-induced lytic response of NK cells. Co-culture of M. avium with large granular lymphocytes augments the ability of such cells to lyse both tumour cells and bacterially infected autologous monocytes;6 such an augmenting effect depended on a direct interaction of bacteria with large granular lymphocytes. Induction of an NK-cell cytotoxic response by bacterial contact – with no apparent involvement of T cells – was also demonstrated by Tarkkanen & Saksela. They found that co-culture of PBMCs with glutaraldehyde-fixed salmonellae augmented the cytotoxic capacity of PBMCs against NK-sensitive targets.11 Non-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted cytotoxicity of human mononuclear cells stimulated with secreted mycobacterial proteins, or other mycobacterial soluble antigens, was previously described by Ravn et al.10 In this case, however, it was suggested that cytokines released by mycobacterial antigen-activated CD4+ T lymphocytes induced non-MHC-restricted cytotoxicity. It is possible that different mechanisms of induction of NK-cell functions may occur, depending on the type of antigen (soluble versus particulate) and/or the stage of infection of a naive host. Early during infection, in the absence of an antigen-specific T-cell response, a direct interaction between mycobacteria and NK cells could promote their activation, proliferation, cytokine production and lytic activity. Such a mechanism could ensure a sufficient level of macrophage-activating cytokines (mainly IFN-γ) or of cytotoxic activity against infected cells, when the majority of macrophages may be inefficiently equipped to destroy intracellular bacteria. At subsequent time-points after infection, antigen-specific activated T lymphocytes could control NK cell functions via the release of activating (IL-2) or inhibitory (IL-4) cytokines. On the other hand, NK cells can influence the critical decision of Th1 versus Th2 T-cell development through release of IFN-γ when antigen-specific T cells are starting to undergo clonal expansion and differentiation. Thus, besides their role during the early phases of infection of a naive host, NK cells may also contribute to the antigen-induced protection mediated by antigen-specific T lymphocytes.

Altogether, the results presented in this article provide evidence that a direct interaction with mycobacterial cells may represent an additional mechanism of human NK cell activation that promotes their proliferation, IFN-γ production and cytotoxic activity. Activating NK cell receptors with the ability to interact with bacterial pathogens/products remains a poorly investigated area. It has been reported that lactobacilli interact with asialo-GM1 receptors on epithelial cells.37,38 Expression of this receptor on murine NK cells has also been reported39 and it may also constitute a putative receptor on human NK cells to mediate activation by (myco)bacteria.40 Other possible candidates may be the Toll-like receptors (TLR), a family of mammalian pattern-recognition proteins widely expressed on innate immune cells. Recent work has identified specific TLR proteins (e.g. TLR-2, TLR-4) that recognize distinct mycobacterial products, which are either cell wall-associated or secreted.41 Interestingly, very recently, it has been reported that Leishmania lipophosphoglycan activates human NK cells through TLR-2,42 suggesting that NK cells are indeed capable of the direct recognition of, and activation by, pathogens. It has also been reported that both opsonized and non-opsonized mycobacteria may interact with complement receptor-3, a phagocyte and NK cell-membrane receptor with multiple ligand specificities and functions.41,43

Identifying the mycobacterial components and NK cell-surface molecules able to interact will raise the possibility of developing NK-oriented strategies for effective vaccination of naive individuals against infections where Th1-dependent immune responses are beneficial.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the EU BIOMED 2 Programme, contract BMH4-CT97-2671, and by ‘Progetti M.I.U.R.’ protocols N°MM06248818-001, N°2001063758-002 and N°2002067349-001 Rome, Italy.

References

- 1.Kaufmann SHE. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bancroft GJ. The role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:503–10. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90030-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robertson MJ, Ritz J. Biology and clinical relevance of human natural killer cells. Blood. 1990;76:2421–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufmann SHE. Immunity to intracellular bacteria and protozoa. Immunologist. 1995;3:221–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scharton TM, Scott P. Natural killer cells are source of interferon γ that drives differentiation of CD4+ T cell subsets and induce early resistance to Leishmania major in mice. J Exp Med. 1993;178:567–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard DK, McMillen S, Hoffman SL, Djeu JY. Mycobacterial induction of activated killer cells: possible role of tyrosine kinase activity in interleukin-2 receptor alpha expression. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2843–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2843-2849.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haller D, Blum S, Bode C, Hammes WP, Schiffrin EJ. Activation of human blood mononuclear cells by nonpathogenic bacteria in vitro: evidence of NK cells as primary targets. Infect Immun. 2000;68:752–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.752-759.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klimpel GR, Nielsen DW, Asuncion M, Klimpel KD. Natural killer cell activation and interferon production by peripheral blood lymphocytes after exposure to bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;56:1436–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.6.1436-1441.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindemann RA. Roles of interferon and cellular adhesion molecules in bacterial activation of human natural killer cells. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1702–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1702-1706.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravn P, Pedersen BK. Non-major histocompatibility complex-restricted cytotoxic activity of blood mononuclear cells stimulated with secreted mycobacterial proteins and other mycobacterial antigens. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5305–11. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5305-5311.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarkkanen J, Saksela E. Potentiation of human natural killer cell cytotoxicity by Salmonella bacteria is an interferon- and interleukin-2-independent process that utilizes CD2 and CD18 structures in the effector phase. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2767–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2767-2773.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarkkanen J, Saksela E, Lanier LL. Bacterial activation of human natural killer cells: characteristics of the activation process and identification of the effector cell. J Immunol. 1986;137:2428–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarkkanen J, Saxén H, Nurminen M, Mäkelä PH, Saksela E. Bacterial induction of human activated lymphocyte killing and its inhibition by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) J Immunol. 1986;136:2662–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Junqueira-Kipnis AP, Kipnis A, Jamieson A, Juarrero MG, Diefenbach A, Raulet DH, Turner J, Orme IM. NK cells respond to pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, but play a minimal role in protection. J Immunol. 2003;171:6039–45. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harshan KV, Gangadharam PRJ. In vivo depletion of natural killer cell activity leads to enhanced multiplication of Mycobacterium avium complex in mice. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2818–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2818-2821.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorgat F, Keraan MM, Luckey PT, Ress S. Evidence for in vivo generation of cytotoxic cells. PPD-stimulated lymphocytes from tuberculous pleural effusions demonstrate enhanced cytotoxicity with accellerated kinetics of induction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:418–23. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okubo Y, Nakata M, Kuroiwa Y, Wada S, Kusama S. NK cells in carcinomatous and tuberculous pleurisy: phenotypic and functional analyses of NK cells in peripheral blood and pleural effusions. Chest. 1987;92:500–4. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ota T, Okubo Y, Sekiguchi M. Analysis of immunological mechanisms of high natural killer cells activity in tuberculous pleural effusions. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:29–33. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molloy A, Meyn PA, Smith KD, Kaplan G. Recognition and destruction of bacillus Calmette-Guérin-infected human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1691–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz P, Yeager H, Whalen G, Evans M, Swartz RP, Roecklein J. Natural killer cell-mediated lysis of Mycobacterium avium complex-infected monocytes. J Clin Immunol. 1990;10:71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00917500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denis M. Interleukin-12 (IL-12) augments cytolytic activity of natural killer cells towards Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected human monocytes. Cell Immunol. 1994;156:529–36. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bermudez LE, Wu M, Young LS. Interleukin-12-stimulated natural killer cells can activate human macrophages to inhibit growth of Mycobacterium avium. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4099–104. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4099-4104.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bermudez LE, Young LS. Natural killer cell dependent mycobacteriostatic and mycobactericidal activity in human macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;146:265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brill KJ, Li Q, Larkin R, Canaday DH, Kaplan DR, Boom WH, Silver RF. Human natural killer cells mediate killing of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv via granule-independent mechanisms. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1755–65. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1755-1765.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esin S, Batoni G, Källenius G, Gaines H, Svenson SB, Campa M, Andersson R, Wigzell H. Proliferation of distinct human T cell subsets in response to live, killed and soluble bacterial extracts of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. avium. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:419–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batoni G, Bottai D, Maisetta G, Pardini M, Boschi A, Florio W, Esin S, Campa M. Involvement of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis secreted antigen SA-5K in intracellular survival of recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;205:125–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batoni G, Esin S, Harris RA, Källenius G, Svenson SB, Andersson R, Campa M, Wigzell H. γδ+ and CD4+αβ+ human T cell subset responses upon stimulation with various Mycobacterium tuberculosis soluble extracts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;112:52–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pala P, Hussell T, Openshaw PJM. Flow cytometric measurement of intracellular cytokines. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:107–24. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer K, Andreesen R, Mackensen A. An improved flow cytometric assay for the determination of cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. J Immunol Methods. 2002;259:159–69. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esin S, Batoni G, Saruhan-Direskeneli G, et al. In vitro expansion of T cell receptor Vα2.3+ CD4+ T lymphocytes in HLA-DR17(3), DQ2+ individuals upon stimulation with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3800–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3800-3809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Unanue ER. Studies in listeriosis show the strong symbiosis between the innate cellular system and the T-cell response. Immunol Rev. 1997;158:11–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batoni G, Esin S, Pardini M, Bottai D, Senesi S, Wigzell H, Campa M. Identification of distinct lymphocyte subsets responding to subcellular fractions of Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guérin. Clin Exp Immunol. 2000;119:270–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGuirk P, Mills KHG. Pathogen specific regulatory T cells provoke a shift in the Th1/Th2 paradigm in immunity to infectious diseases. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:450–5. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giacomini E, Iona E, Ferroni L, Miettinen M, Fattorini L, Orefici G, Julkunen I, Coccia EM. Infection of human macrophages and dentritic cells with Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces a differential cytokine gene expression that modulate T cell response. J Immunol. 2001;166:7033–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshihara R, Shiozawa S, Fujita T, Chihara K. Gamma interferon is produced by human natural killer cells but not T cells during Staphylococcus aureus stimulation. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3117–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3117-3122.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rook GAV, Steele J, Fraher L, Barker S, Karmali R, O'Riordan J, Stanford J. Vitamin D3, γ-interferon, and control of proliferation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by human monocytes. Immunology. 1986;57:159–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fujiwara S, Hashiba H, Hirota T, Forstner JF. Proteinaceous factor(s) in culture supernatant fluids of bifidobacteria which prevents the binding of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli to gangliotetraosylceramide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:506–12. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.506-512.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamamoto K, Miwa T, Taniguchi H, Nagano T, Shimamura K, Tanaka T, Kumagai H. Binding specificity of Lactobacillus to glycolipids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:148–52. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohteki T, Fukao T, Suzue K, Maki C, Ito M, Nakamura M, Koyasu S. Interleukin 12-dependent interferon gamma production by CD8alpha1 lymphoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1981–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muller C, Szangolies M, Kukel S, Kiehl M, Sorice M, Griggi T, Lenti L, Bauer R. Characterization of autoantibodies to natural killer cells in HIV-infected patients. Scand J Immunol. 1996;43:583–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-80.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Crevel R, Ottenhoff TH, van der Meer JW. Innate immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:294–309. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.294-309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker I, Salaiza N, Aguirre M, et al. Leishmania lipophosphoglycan (LPG) activates NK cells through toll-like receptor-2. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;130:64–75. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(03)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ross GD, Vetvicka V. CR3 (CD11b, CD18). a phagocyte and NK cell membrane receptor with multiple ligand specificities and functions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;92:181–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]