Abstract

The arrival of bone marrow T-cell progenitors to the thymus, and the directed migration of thymocytes, are thought to be regulated by the expression of chemokines and their receptors. Recent data has shown that the Jak\Stat signalling pathway is involved in chemokine receptor signalling. We have investigated the role of Jak 3 in chemokine-mediated signalling in the thymus using Jak 3–\– mice. These mice show defects in T-cell development, as well as in peripheral T-cell function, resulting in a hypoplastic thymus and an altered T-cell homeostasis. Here we demonstrate, for the first time, that bone marrow progenitors and thymocytes from Jak 3–\– mice have decreased chemotactic responses to CXCL12 and CCL25. We also show that Jak 3 is involved in signalling through CCR9 and CXCR4, and that specific inhibition of Jak 3 in wild-type progenitors and thymocytes decreases their chemotactic responses towards CCL25 and CXCL12. Finally, quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction analysis showed that thymocytes from Jak 3–\– mice express similar levels of CXCR4 and CCR9 compared to wild-type mice. Altogether, deficient CCL25- and CXCL12-induced migration could result in a homing defect of T-cell progenitors to the thymus, as well as in a deficient thymocyte migration through the thymic stroma. Our results strongly suggest that the absence of Jak 3 affects T-cell development, not only through an impaired interleukin-7 receptor (IL-7R)-mediated signalling, but also through impaired chemokine-mediated responses, which are crucial for thymocyte migration and differentiation.

Keywords: chemokine, Janus kinases, signaling, T-cell development, thymus

Introduction

T-cell development takes place in the thymus and involves different proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis processes. The ultimate outcome of this process is the maturation of a self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted, self-tolerant repertoire of mature CD4+ and CD8++ T cells.1 The stages of T-cell development can be identified by examining the surface expression of CD4 and CD8 on thymocytes: double negative (DN) (CD4– CD8–); double positive (DP) (CD4+ CD8+); CD4 single positive (CD4SP); and CD8 single positive (CD8SP).2 During the DN stage, pre-T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling allows the transition from DN to DP,3 which are the first cells to express a mature TCR-αβ and undergo positive and negative selection.4 Positive selection promotes the maturation of thymocytes whose TCRs are able to recognize peptide–MHC complexes on cortical epithelial cells with low avidity, while negative selection is responsible for the elimination of thymocytes whose TCRs have a very high avidity for peptide–MHC complexes primarily expressed by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells.

It has been demonstrated that both cellular interactions and soluble factors are required for T-cell development.5 Among these, chemokines have been implicated in the homing of T-cell progenitors to the thymus,6 in the migration of thymocytes through the thymic stroma,7 as well as in the exit of mature thymocytes and homing to secondary lymphoid organs.8 Recently, it was shown that the ability of thymocytes to respond to chemokines is modulated through their differentiation.9 Furthermore, chemokines are differentially expressed in distinct stromal compartments,10 thereby defining specific microenviroments that allow the migration of immature thymocytes from the subcapsular region, through the thymic cortex and into the medulla.

Chemokines are a superfamily of small, inducible, secreted, proinflammatory chemotactic cytokines involved in a variety of immune responses and acting primarily through G protein-coupled, seven-transmembrane-domain receptors. There is growing evidence that the Jak/Stat pathway participates in chemokine signalling.11,12 It has been shown that the Janus kinase 2 (Jak 2) is phosphorylated upon stimulation with the chemokines CCL2,13 CCL514 and CXCR4.15 Our laboratory has been interested in a related kinase, Jak 3, which is expressed mainly by haematopoietic cells and is associated with the common γ chain (γc), shared by the cytokine receptors to interleukin (IL)-2, -5, -7, -9 and -15.16 Upon ligand binding, Jak 3 phosphorylates Stat proteins, which then heterodimerize and translocate into the nucleus, where they act as activators of transcription of specific genes.17,18

Analysis of the Jak 3–/– mouse phenotype shows a severely hypoplastic thymus, which nevertheless is able to generate almost normal numbers of T cells,19 although with several unusual characteristics.20–22 The number of thymocytes in these mice is reduced by 10–100-fold, when compared with normal mice, but in adult mice, the subpopulations DN, DP, CD4 and CD8 appear to have an equal distribution, as in normal mice. The phenotype of Jak 3–/– mice resembles that of IL-7-, IL-7 receptor (IL-7R)-, and γc-deficient mice.23 Jak 3 is constitutively associated with the IL-7R γc chain and therefore the defect in T-cell development in these mice has been explained by the lack of IL-7-mediated signalling, which acts as a survival and proliferation factor at the early DN stage.24 However, a more detailed analysis of Jak 3–/– mice has shown that the thymic defect occurs at a very early stage in T-cell development, more specifically between days 14 and 15 of fetal life.25 One possible explanation for the decrease in early T-cell progenitors is a diminished migration from the bone marrow to the thymus. In this context, CXCL12 and CCL25, and their receptors CXCR4 and CCR9, respectively, have been proposed to participate in the recruitment of T-cell progenitors to the thymus,6 as well as in the migration of immature thymocytes through the thymic stroma.7

This evidence led us to investigate chemokine-mediated responses in Jak 3–/– mice. Here we show that Jak 3 participates in chemokine signalling through CCR9 and CXCR4 in bone marrow progenitors and thymocytes. Our results demonstrate that the T-cell development defect observed in Jak 3–/– mice may be, in part, the result of a decreased migration of thymic progenitors from the bone marrow to the thymus, and/or because of a decreased migration through the different thymic compartments. Furthermore, this decrease may be explained by an impaired signalling through specific chemokine receptors, as no significant differences in chemokine receptor expression were seen in Jak 3–/– mice when compared with wild-type mice.

Materials and methods

Cytokines

Mouse recombinant IL-7 (rIL-7), and the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1β (MIP-1β)/CCL4, regulated on activation, normal, T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES)/CCL5, eotaxin/CCL11, and stromal-cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α)/CXCL12, were obtained from Peprotech (New Jersey, NJ); TECK/CCL25 was obtained from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Antibodies

Anti-phosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (mAb) (4G10) was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Rabbit anti-Jak 3 antisera 888 was kindly provided by Dr Leslie J. Berg (University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA). Polyclonal goat anti-Jak 3 (sc-1078) was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and rabbit anti-Jak 3 from Upstate Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labelled anti-mouse and anti-rabbit immmunoglobulins (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Inc., NJ) were used as secondary reagents in Western blotting assays. For fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis, bone marrow cells were stained with mAbs against phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Sca-1 (clone 2B8; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) and biotinylated c-kit (clone E13-161.7), followed by streptavidin-conjugated fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC). Stained cells were analysed by flow cytometry using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

Mice

Jak 3–/– mice (C57BL/6-JAK 3tm1Ljb) and C57/BL6 mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and from Dr Leslie J. Berg (University of Massachusetts Medical Center). Four- to 10-week-old homozygous Jak 3-deficient (–/–) mice and their heterozygous (+/–) littermates were used in our experiments. In some experiments, age-matched C57/BL6 mice were used as controls.

Preparation of thymocytes and bone marrow cells

Thymocytes were prepared after mechanical disgreggation of thymic glands, using a 50-µm nylon mesh. They were washed twice with Hanks' balanced salt solution buffer (HBSS) before use for chemotaxis, calcium flux and phosphorylation analysis. Bone marrow cells were obtained from the femurs of 4–10-week-old female C57/BL6 mice and from the Jak 3–/– mice, as described previously.26

Chemotaxis assays

Cell migration assays were performed using a 48-well modified Boyden microchemotaxis chamber, as described previously.27 Briefly, increasing concentrations (0–1000 ng/ml) of the chemokines were tested in the lower wells of the chamber. A sample of 5 × 106 cells from Jak 3–/–, Jak3+/– or wild-type (C57/BL6) mice were resuspended in chemotaxis medium [HBSS containing 0·05% bovine serum albumin (BSA)] and allowed to migrate through collagen-coated pore polycarbonate membranes (Neuroprobe, Gaithersburg, MD). After 2 hr, membranes were Diff-Quick-stained and migrating cells were counted in a high-power field. Alternatively, cells were fluorescently labelled with 1 µg/ml calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 15 min at 37°, in 5% CO2, washed twice with HBSS and resuspended at 5 × 106 cells/ml in chemotaxis medium. Chemotaxis was performed as described above, and migrating cells were quantified using a Molecular Imager (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The viability of cells was assessed, prior to the chemotaxis assay, by Trypan blue exclusion staining.

For inhibition experiments, thymocytes or bone marrow cells from C57/BL6 mice [8 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 + 10% fetal calf serum (FCS)] were resuspended in medium containing the specific Jak 3 inhibitor, WH1-P131 (30 µg/ml; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), pertussis toxin (PTX, 200 ng/ml; Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO), or dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) (3 µl), and incubated for 1 hr at 37°. Under these conditions, treatment with neither inhibitor nor DMSO affected viability, as assessed with Trypan blue exclusion staining. Cells were then washed twice with HBSS and tested in chemotaxis assays, as described above.

Transwell chemotaxis ssays

Chemotaxis assays were performed using 24-transwell chambers (5 µm pore size; Corning Inc., Acton, MA), as described previously,28 with minor modifications. Briefly, bone marrow cells obtained from wild-type C57/BL6 and Jak 3–/– mice were resuspended in chemotaxis buffer (HBSS buffer plus 0·1% BSA) at a density of 5 × 106 cells/ml. The bottom chamber was filled with 0·6 ml of chemotaxis buffer containing varying concentrations of murine CXCL12 and CCL25 chemokines. An aliquot of 0·1 ml of the cell suspension was added to the top of the chamber. The plates were incubated for 2 hr at 37° in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells that migrated to the bottom chamber were harvested and stained with the mAbs anti-Sca-1 and anti-c-kit, as described above.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak 3

Thymocytes were isolated and incubated in starving medium (RFM: RPMI 1640 containing 0·5% FCS) for 2 hr at 37°. Cells were then washed once with RFM and 3 × 107 cells were resuspended in 300 µl of either RFM or the same medium containing chemokines (50–100 ng/ml), and incubated at 37° for up to 60 seconds. Time-course experiments showed no increase in phosphorylation after 60 seconds. As a positive control, cells were incubated with rIL-7 (100 ng/ml) for 3 min at 37°. Stimulations were terminated and total lysates prepared in 1% Triton-X-100 lysis buffer, containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors, as previously described.29 Supernatants were first incubated with goat anti-Jak 3 (sc-1078) and then immunoprecipitated with recombinant protein G–sepharose (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Immunoprecipitates and total lysates were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE; 10% gel) and transferred to Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). For phosphotyrosine analysis, Western blots were performed using anti-phosphotyrosine immunoglobulin (4G10) followed by HRP-labelled anti-mouse immunoglobulin. Membranes were developed by chemoluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia). As a control for protein loading, blots were stripped and reprobed with rabbit anti-Jak 3 serum (888) or with rabbit anti-Jak 3 (Upstate Biotechnology). Densitometry analysis was performed on the blots using an FX Imager (Bio-Rad) and phosphorylation was calculated as the ratio of PY : Jak 3.

Real-time PCR

For reverse transcription (RT), total RNA was isolated from C57/BL6 or JAK 3–/– of thymocytes using RNA-60 (Tel-Test Inc., Friendslaw, TX) according to manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was synthesized from Dnase I (Invitrogen)-treated total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and oligo dT.

Real-time PCR was performed by amplifying 2 µl of cDNA (10% of the total cDNA yield) with the SYBR Green PCR Core Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) on a ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). Amplification conditions were 95° for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94° for 45 seconds, 60° for 45 seconds, and 72° for 45 seconds. Following amplification, a melting point program was run to create melting profiles for each reaction described. The number of PCR cycles required for SYBR Green fluorescence to cross a threshold where there was a significant increase in change in fluorescence (CT = threshold cycle) was obtained using ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System Software. Total cDNA input was normalized to mouse hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) expression measured in parallel polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions. Real-time PCR data are presented as relative expression using the ΔΔCT method in which relative expression=2–ΔΔCT, where:

Each sample was run in triplicate and threshold cycle (Ct) values were averaged from each reaction. These results were used to calculate the relative amount of each chemokine receptor mRNA present in Jak 3–/– mice compared to wild-type mice. The PCR products were analysed on a 2% (w/v) agarose gel to confirm purity and size of the product. Primers used in the PCR amplification were as follows: CXCR4 sense 5′-AGAAGCTAAGGAGCATGACGGA-3′, CXCR4 antisense: 5′-ACTGCCTTTTCAGCCAGCAGTT-3′; CCR9 sense: 5′-CAGGCAGCTGCAGTGGTCCTCTCCC-3′, CCR9 antisense: 5′-TGTGCAAGGCTGGGCTGTCTTTGC-3′; and HPRT sense 5′-CCTGCTGGATTACATTAAGGCACTG-3′; HPRT antisense: 5′-GTCAGGGGCATATCCAACAACAAAC-3′.

For analysis of RT–PCR data, the program Qgene was used.30 The mean of the normalized expression was calculated by averaging the CT values (of the target and of the reference) and subsequent calculation of the mean normalized expression (eqn 3, according to ref. 30). The calculation of the normalized expression is supported by the amplification efficiency values calculated from the amplification efficiency plots constructed for each gene. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was performed to assess the significance level of expression differences in the two groups. P-values of <0·05 were considered significant.

Results

Jak 3-deficient thymocytes have a decreased chemotactic response towards CCL25 and CXCL12

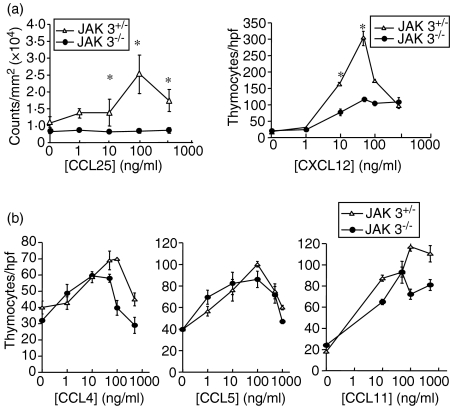

The fact that Jak 3-deficient mice present an hypoplastic thymus, and the involvement of the Jak/Stat pathway in chemokine-mediated signalling, led us to postulate that chemokine-mediated responses might be impaired in Jak 3–/– thymocytes. To investigate the functional responses to chemokines, we first performed chemotaxis assays using thymocytes obtained from Jak 3–/– or Jak 3+/– mice. Among thymus-expressed chemokines we focused our attention towards CCL25 and CXCL12, which have been implicated in the homing of T-cell progenitors to the thymus and in chemokine-induced migration through different stromal compartments. For these experiments, total thymocytes were isolated from 4–10-week-old mice and tested for their chemotactic response towards increasing amounts (0–500 ng/ml) of the thymic chemokines CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, CCL25 and CXCL12. Figure 1(a) shows that Jak 3–/– thymocytes have decreased chemotactic responses towards CCL25 and CXCL12, compared to Jak 3+/– thymocytes. The differences in migration were seen throughout the dose–response curve. In contrast, Jak 3–/– thymocytes showed a chemotactic response towards CCL5, CCL11 and CCL4 which was not significantly different to that observed in Jak 3+/– mice (Fig. 1b). These results demonstrate that Jak 3 is required for optimal migration towards CCL25 and CXCL12, suggesting that in thymocytes this kinase may be involved in the signalling pathways of the chemokine receptors CCR9 and CXCR4, respectively. Conversely, the differences in migration might not be directly mediated by a deficient signalling through chemokine receptors, but rather by other thymocyte intrinsic defects or extrinsic factors present in the Jak 3-deficient thymus. On the other hand, the lack of differences observed in the chemotactic responses towards CCL4, CCL5 and CCL11, between Jak 3–/– and Jak 3+/–, may be explained by differences in chemokine receptor usage.

Figure 1.

Jak 3-deficient thymocytes have impaired chemotactic responses towards CXCL12 and CCL25. Total thymocytes were isolated from 4–10-week-old Jak 3–/– or Jak+/– mice and allowed to migrate, in a chemotaxis assay, in the presence of 0–1000 ng/ml chemokines, as described in the Materials and methods. (a) Chemotaxis responses of thymocytes from Jak 3-deficient thymocytes and their heterozygous littermates, to chemokines CXCL12 and CCL25. Left panel, cells were stained with calcein-AM prior to the chemotaxis assay, and migrated cells were quantified as described in the Materials and methods. Results are from one representative experiment (n = 5) and expressed as counts/mm2 (× 104). Right panel, number of thymocytes that migrated through the membrane were counted by microscopy in a high-power field (hpf). (b) Chemotaxis assays towards CCL4, CCL5 and CCL11. The cells that migrated through the membrane were counted by microscopy in a hpf. The data are from representative experiments (n = 5) showing the mean ± standard error (SE) of eight different fields counted under microscopy in a hpf of replicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Asterisks indicate a P-value of < 0·05.

Bone marrow progenitors show a decreased chemotactic response towards CCL25 and CXCL12

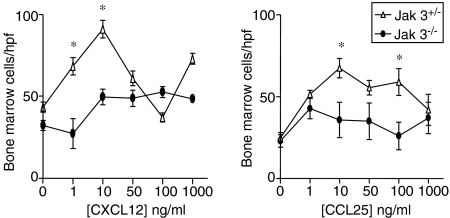

We have demonstrated that Jak 3-deficient thymocytes show decreased migration in response to the thymic chemokines CCL25 and CXCL12. These chemokines have been implicated in T-cell progenitor recruitment to the thymus.6 To elucidate whether the absence of Jak 3 would also affect the response of bone marrow progenitors, we analysed the chemotactic response of bone marrow cells from Jak 3–/– and Jak 3++/– mice to increasing amounts of CCL25 and CXCL12 (0–1000 ng/ml). Fig. 2 shows that, as found with Jak 3–/– thymocytes, Jak 3–/– bone marrow cells also have a decreased chemotactic response towards CCL25 and CXCL12 when compared with Jak 3+/– bone marrow cells. In order to characterize the cell subsets that migrated in our chemotaxis assays we performed transwell experiments and stained the migrated cells with Sca-1 and c-kit mAbs. As shown in Fig. 3(a), total bone marrow from wild-type and Jak 3–/– mice contain a low percentage of Sca-1+, c-kit+ haematopoietic progenitors (1·5% and 0·5% of the total bone marrow cells, respectively), which fall within the range of percentage of progenitors reported in normal adult mice.31,32Fig. 3(b) shows that cells which migrated towards CXCL12 and CCL25 were enriched in Sca-1+, c-kit+ cells. These results suggest that a homing defect of bone marrow progenitors to the thymus may contribute to the thymic deficiency present in Jak 3–/– mice.

Figure 2.

Jak 3–/– bone marrow progenitors show diminished migration towards CXCL12 and CCL25. Data represent chemotaxis assays of bone marrow progenitors isolated from 4–10-week-old Jak 3–/– mice or age-matched wild-type mice. Bone marrow progenitors were isolated from the femurs of Jak 3–/– and Jak 3+/+ mice and allowed to migrate in a chemotaxis assay in the presence of 0–1000 ng/ml of chemokines. Left panel, data showing chemotactic responses to CCL25. Right panel, data representing chemotactic responses to CXCL12. The data shown are from representative experiments (of a total of five) showing the mean ± standard error (SE). The cells that migrated through the membrane were counted in eight different fields under microscopy in a high-power field (hpf) of replicate wells. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test. Asterisks indicate a P-value of < 0·05.

Figure 3.

Haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors respond to CXCL12 and CCL25. Total bone marrow cells from wild-type and Jak 3–/– mice were stained with Sca-1- and c-kit-specific antibodies to characterize the percentages of haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors in these mice. A representative experiment (out of five) is shown in (a). Total bone marrow cells from C57/BL6 mice were subjected to chemotaxis assays using a transwell technique (b). As shown, a significant percentage of the migrated cells towards CXCL12 and CCL25 (10 ng/ml of chemokine), were positive for Sca-1 and c-kit. A representative experiment (of a total of three) is shown.

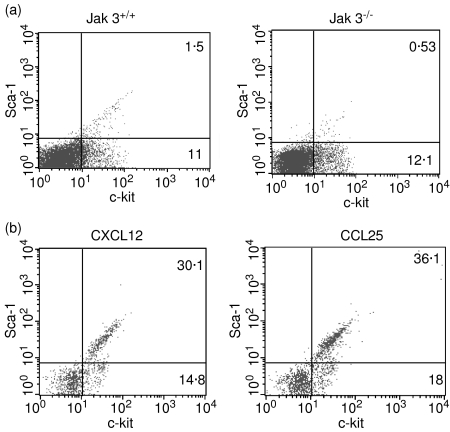

Pharmacological inhibition of Jak 3 results in a decreased migration of normal thymocytes and bone marrow progenitors to CCL25 and CXCL12

To further support the role of Jak 3-mediated signalling in the chemotactic response of thymocytes to CCL25 and CXCL12, we determined whether the pharmacological inhibition of Jak 3 would directly affect the migration of normal wild-type thymocytes towards these chemokines. We used the drug WHI-P131, which has been reported to be highly specific for Jak 3 and does not inhibit Jak 1 and Jak 2, nor the TEC family kinase Btk, Syk, or the Src kinase, Lyn.33 As shown in Fig. 4(a), inhibition of Jak 3 by WHI-P131 almost completely abrogated the chemotactic response of thymocytes to CCL25 and CXCL12, although differences were observed in the dose–response curves obtained with CXCL12 (this effect was apparent at lower doses of the chemokine). In these experiments we also used PTX, which blocks the function of Gαi protein-associated chemokine receptors. As expected, pretreatment of thymocytes with PTX completely blocked the chemotactic response of thymocytes to both CCL25 and CXCL12. In contrast, the chemotactic response of WHI-P131-treated thymocytes to CCL11 was inhibited to a lesser extent, possibly indicating that in thymocytes, Jak 3 is involved in CCR9 and CXCR4 signalling, but may not be completely required for CCR3-mediated function. Similar experiments were performed using bone marrow cells from wild-type mice treated with the same inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 4(b), treatment of bone marrow cells with WHI-P131 resulted in a decrease in the migratory responses towards CCL25 and CXCL12, when compared with untreated cells. Altogether, these data further confirm that Jak 3 is involved in the signalling pathways of chemokine receptors CCR9 and CXCR4, respectively.

Figure 4.

Pharmacological inhibition of Jak 3 abrogates the chemotactic response of normal thymocytes to CCL25 and CXCL12. Total thymocytes (a) or bone marrow cells (b) from adult mice were preincubated with inhibitor WHI-P131, or pertussis toxin (PTX), and allowed to migrate in a chemotaxis assay in the presence of 0–1000 ng/ml of the specific chemokine. Cells were stained with calcein prior to performing the chemotaxis assay. Migration was calculated as counts of fluorescence/mm2, measured using an FX Imager, as described in the Materials and methods. Representative experiments are shown (n=3). The response to CCL25 (left) and CXCL12 (centre), was greatly decreased in WHI-P131-treated thymocytes, while a lower inhibition was observed in the chemotactic response towards CCL11 (right). The Gαi inhibitor, PTX, completely blocked chemotaxis towards all chemokines tested. Bars represent the mean of triplicate wells ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

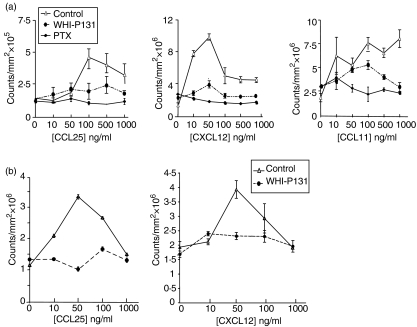

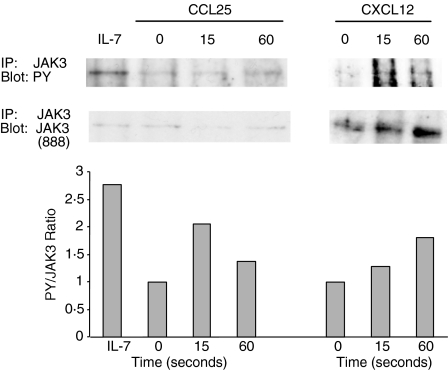

CCL25 and CXCL12 induce tyrosine phophorylation of JAK 3 in thymocytes

As Jak 3–/– thymocytes showed a decreased chemotactic response towards CXCL12 and CCL25, we proceeded to demonstrate Jak 3 involvement in CXCR4- and CCR9-mediated signalling. For this purpose, we performed tyrosine phosphorylation analysis of normal thymocytes upon stimulation with CCL25 and CXCL12. Thymocytes from 4–10-week-old mice were isolated and stimulated for 15 and 60 seconds with chemokines, or for 3 min with rIL-7, as a positive control. Total lysates were prepared, immunoprecipitated with anti-Jak 3 immunoglobulin and then analysed in Western blots using anti-phosphotyrosine immunoglobulin. The level of phosphorylated Jak 3 was normalized to the total amount of Jak 3 protein, as described in the Materials and methods. As shown in Fig. 5, after stimulation with rIL-7, Jak 3 became strongly tyrosine phosphorylated, as IL-7R contains the γc chain, which is constitutively associated with Jak 3. Interestingly, Jak 3 also became tyrosine phosphorylated after stimulation with CCL25 and CXCL12, although the level of phosphorylation was always lower than that observed after IL-7 stimulation. Tyrosine phosphorylation in response to chemokines occurred as early as 15 seconds after stimulation, and reached a peak between 15 and 60 seconds. Later time-points were also analysed but did not show increased levels of phosphorylation (data not shown). These results demonstrate that in murine thymocytes Jak 3 has a role in mediating signalling through CCR9 and CXCR4 after stimulation with their natural ligands.

Figure 5.

CCL25 and CXCL12 induce tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak 3. A representative experiment of n = 5 is shown. Thymocytes (30 × 106) from 4–10-week-old C57/BL6 mice were stimulated with CXCL12 or CCL25 for 15 and 60 seconds, and Jak 3 phosphorylation was analysed after immunoprecipitation and blotting with the phosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10 (top panel). As a positive control, thymocytes were stimulated with recombinant interleukin-7 (IL-7) (100 ng/ml) After stripping, the membrane was reprobed with Jak 3 polyclonal antisera (888) (bottom panel). Densitometric analysis was performed on phosphotyrosine and Jak 3 blots, and the phosphorylation level of Jak 3 was calculated as the ratio of the densitometric intensities of the anti-phosphotyrosine signal to the anti-Jak 3 signal of the respective bands. The data were normalized to the values obtained with thymocytes treated in media alone.

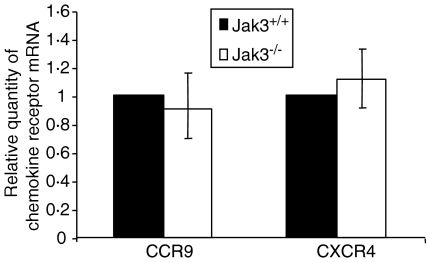

Jak 3–/– thymocytes express normal levels of CCR9 and CXCR4

The differential chemotactic responses towards CCL25 and CXCL12, observed in Jak 3–/– thymocytes, might be caused by an impaired signalling through specific chemokine receptors and/or by a decreased expression of chemokine receptors. In order to further clarify the origin of the diminished migration of Jak 3–/– thymocytes, we decided to characterize the expression of chemokine receptors in these cells by real-time PCR. Total RNA obtained from purified adult C57/BL6 and JAK 3–/– thymocytes was reverse transcribed into cDNA and amplified by PCR utilizing specific exonic sequences. Data obtained with the CCR9- and CXCR4-specific primers were normalized with their corresponding HPRT controls, as described in the Materials and methods. As shown in Fig. 6, CCR9 and CXCR4 mRNA expression in Jak 3–/– thymocytes was not significantly different from that in wild-type mice. This indicates that an impairment of CCR9- and CXCR4-mediated signalling in Jak 3–/– cells, rather than differences in chemokine receptor expression, may be responsible for the deficient migration of thymocytes and/or bone marrow progenitors towards CCL25 and CXCL12.

Figure 6.

Expression of CCR9 and CXCR4 in Jak 3–/– thymocytes. Real time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was performed on cDNA obtained from total RNA (DNase treated) isolated from 6-week-old Jak 3–/– and C57/BL6 mice (pools of six mice). Murine CCR9-, CXCR4- and HPRT-specific primers were used in the PCR and amplified using an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System. Data show a representative experiment (of a total of six) performed in triplicate. Data (mean ± standard deviation) are plotted as relative chemokine receptor (CKR) mRNA, calculated by normalizing the values obtained with the CCR9 and CXCR4 primers with their respective HPRT controls, as described in the Materials and methods. Analysis of significance was performed using the program Qgene, as previously described.30

In parallel, we analysed chemokine receptor expression in bone marrow progenitors. Total RNA was extracted from pooled C57/BL6 wild-type and Jak 3–/– mice, and cDNA was amplified using CCR9- and CXCR4-specific primers, as described above. Analysis of CCR9 expression by real-time PCR showed that the levels of CCR9 from total bone marrow cells were out of the range of detection. These results might be explained by the potentially low number of CCR9-expressing cells in total bone marrow, as haematopoietic progenitors constitute a low percentage of total adult bone marrow.31 CXCR4 expression was not significantly different between wild-type and Jak 3–/– mice (not shown).

Discussion

Jak 3–/– mice show a phenotype which is very similar to that of IL-7 and IL-7R and γc chain–/– mice. This phenotype was initially explained by the absence of signalling through the γc chain, affecting the response of thymocytes to cytokines such as IL-7, which is known to be a crucial survival factor in early T-cell development.24 However, another possible factor contributing to the thymic defect observed in Jak 3–/– mice might be a defect in chemokine receptor signalling towards thymic chemokines. In this context, there is evidence that the Jak/Stat pathway mediates chemokine receptor signalling in different cell types.34 More specifically, Jak 3 has been involved in signalling through CCL2, CCL5, CCL19, CCL21 and CXCL12 in different cell types,8,35 including human CD34+ T-cell progenitors.36 However, no direct evidence has been reported on the role of this family of kinases in chemokine-mediated signalling in murine thymocytes. Here, we demonstrate that in the absence of Jak 3, there is a decreased chemotactic response of bone marrow progenitors and thymocytes towards CCL25 and CXCL12, which are known to play a role in thymocyte migration. This defect in chemotaxis may imply a decreased homing of bone marrow progenitors to the thymus followed by an impaired migration of thymocytes through the different thymic microenviroments.

The deficient CXCL12- and CCL25-mediated migration seen in Jak 3–/– thymocytes cannot be explained by differences in subset composition because, as previously reported, Jak 3 adult thymuses show no differences in the major thymocyte subsets (DN; DP, CD4SP and CD8SP).25

As thymocyte migration was impaired in Jak 3–/– mice, we next analysed whether Jak 3 was involved in the signalling pathway of CCR9 and CXCR4. Indeed, we showed that Jak 3 became tyrosine phosphorylated as early as 15 seconds after the stimulation of normal thymocytes. Although the level of tyrosine phosphorylation seen in response to CXCL12 or CCL25 was lower than that obtained in response to IL-7, it was significant and reproducible in all the experiments performed. Furthermore, similar experiments performed with CCR2-transfected lines have shown comparable levels of phosphorylation in response to CCL2.13 These results are in contrast to data by Zhang et al.,12 who were unable to demonstrate Jak 3 phosphorylation in human CD34+ haematopoietic progenitors in response to CXCL12. However, in another report, Vila-Coro et al.15 demonstrated Jak 3 phosphorylation in response to CXCL12 in human T-cell lines. We believe that these discrepancies may be explained by the use of different cell types or differences between species. In fact, the Jak or Stat molecule, which becomes recruited in response to chemokines, appears to be cell specific.37

In addition, we analysed responses of thymocytes to other thymic chemokines, such as CCL5. We found that there were no significant differences between Jak 3–/– and wild-type thymocytes. This result was unexpected because we demonstrated tyrosine phosphorylation of Jak 3 in CCL5-stimulated thymocytes (data not shown). However, as CCL5 uses two different chemokine receptors (CCR1 and CCR5), it is possible that not all of these receptors transduce signals through Jak 3 in thymocytes, and therefore the chemotactic response to CCL5 may not be affected in the absence of Jak 3.

As further confirmation, we specifically inhibited Jak 3 by using WHI-P131, a specific Jak 3 inhibitor, and showed a decrease in the chemotactic response of thymocytes and bone marrow cells to CCL25 and CXCL12, as well as with PTX, which inhibits Gαi. Our chemotaxis experiments showed that responses to CCL11 were not impaired in Jak 3-deficient thymocytes. These results were further supported by inhibition experiments where WHI-P131 induced only a slight inhibition of the chemotaxis, maintaining the typical dose–response curve, in contrast to that observed with CCL25 and CXCL12, where the chemotactic response was almost completely abrogated.

We have also shown that bone marrow cells migrate less in response to CCL25 and CXCL12. Futhermore, our results showed that the percentages of Sca-1+ c-kit+ cells in wild-type and Jak 3–/– mice were similar to those previously reported in normal adult mice,31 and that a significant percentage of cells that migrated towards CCL25 and CXL12 were indeed haematopoietic progenitors (Sca-1+ c-kit+). This data supports the idea that, in the absence of Jak 3, there is a deficient homing of T-cell progenitors to the thymus. A key role in homing has previously been suggested6 for CCL25 and other thymus-expressed chemokines, although other mechanisms, such as signalling through adhesion molecules, may be involved in the recruitment of T-cell progenitors to the thymus. This is in agreement with recent data where fetal thymocytes from Jak 3–/– mice were analysed and compared with fetal thymocytes of wild-type mice.24 The authors of this work reported that in day-14 thymus, the total numbers of DN1 thymocytes were lower in Jak 3–/– mice than in wild-type mice. As this very early population is not actively dividing, this defect could not be accounted for by the lack of proliferation in response to IL-7, but rather, the lower thymocyte number seemed to indicate a defect in the arrival of early progenitors. In this report, intrathymic injection of fetal liver cells demonstrated that once Jak 3–/– progenitors reached the thymus, they had an intrinsic defect in thymic repopulation because they could not compete with wild-type progenitors.38 However, these experiments did not rule out the possibility of a decreased homing of Jak 3–/– T-cell progenitors to the thymus. We are currently pursuing in vivo transfer experiments to further demonstrate a homing defect.

Migration through the thymic stroma must be tightly regulated. One possible mechanism that would allow such regulation is the developmental expression of chemokine receptors during thymocyte differentiation. Acquisition of chemokine receptors at specific stages of development makes thymocytes able to respond to thymic chemokines. For example, it was shown that CCR9 expression increases after pre-TCR signalling,39,40 allowing DP thymocytes to migrate in response to CCL25, which is produced by cortical epithelial cells and thymic medullary dendritic cells. Similarly, CCR9 expression decreases at the SP stage,41 while CCR7 increases, allowing mature thymocytes to exit the thymus and home to peripheral secondary lymphoid organs.8 In this context, Jak 3–/– mice lack peripheral lymph nodes, which could be explained by the lack of CCR7-mediated signalling in response to CCL19 (G. Soldevila, manuscript in preparation).

Decreased migration of thymocytes and bone marrow progenitors might be explained by deficient chemokine-mediated signalling or by differences in chemokine receptor expression. This latter possibility is supported by a recent report showing that CXCR4 expression in CD34+ thymic progenitors can be up-regulated by IL-7.36 Therefore, a reduction in chemokine receptor expression might be caused by the inability to respond to Jak 3-dependent cytokines, such as IL-7. However, we have shown that Jak 3–/– thymocytes appear to express the same levels of CCR9 and CXCR4 as wild-type mice. In addition, we have demonstrated that CXCR4 expression in Jak 3–/– bone marrow cells is not significantly different from that of wild-type cells. Conversely, CCR9 mRNA expression levels in total bone marrow cells were undetectable. These results are in contrast to those reported recently by Wright et al.,42 who analysed murine haematopoietic stem cells and detected CCR9 expression by RT–PCR, but little or no migration to CCL25. One possible explanation for these contrasting results is that Wright et al. analysed the chemotactic responses of a lineage-negative haematopoietic stem cell population. Nevertheless, this population expresses CXCR4 and responds to CXCL12, which is in agreement with our results. Further enrichment, using specific lineage markers, could improve the detection levels. Therefore, our data indicate that the migration defects detected in Jak 3–/– mice are mainly caused by a deficient signalling through CCR9 and CXCR4.

Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that the impaired chemotactic responses of Jak 3-deficient thymocytes and T-cell precursors is contributed to by other intrinsic defects, such as a defect in integrin-mediated signalling. In this context, chemokines are known to activate integrins by increasing the affinity for their ligands,43 many of which are expressed in the thymic stroma. Adhesion studies are currently being performed to assess the impact of Jak 3 deficiency in integrin-dependent adhesion.

In summary, we have demonstrated that Jak 3 is involved in CCR9- and CXCR4-mediated signalling in the thymus and that Jak 3-deficient bone marrow progenitors and thymocytes show decreased chemotactic responses towards the thymic chemokines, CCL25 and CXCL12. Our studies strongly suggest that the absence of Jak 3 affects T-cell development, not only through impaired IL-7R-mediated signalling, but also through impaired chemokine-mediated responses, which are crucial for thymocyte migration and differentiation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr Edmundo Lamoyi and Dr Vianney Ortíz for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr Leslie J. Berg for providing the 888 Jak 3 antiserum and Jak 3–/– mice. This work was supported by the DGAPA/PAPIIT, grant numbers IN 221199 and IN234002, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. I.L. and A.S. were recipients of a Probetel Fellowship, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

References

- 1.Chan S, Correia-Neves M, Benoist C, Mathis D. CD4/CD8 lineage commitment: matching fate with competence. Immunol Rev. 1998;165:195–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebzda E, Mariathasan S, Ohteki T, Jones R, Bachmann MF, Ohashi PS. Selection of the T cell repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:829–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Boehmer H, Aifantis I, Feinberg J, Lechner O, Saint-Ruf C, Walter U, Buer J, Azogui O, et al. Pleiotropic changes controlled by the pre-T-cell receptor. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:135–42. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Starr TK, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson G, Jenkinson EJ. Lymphostromal interactions in thymic development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1:31–40. doi: 10.1038/35095500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkinson B, Owen JJ, Jenkinson EJ. Factors regulating stem cell recruitment to the fetal thymus. J Immunol. 1999;162:3873–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bleul CC, Boehm T. Chemokines define distinct microenvironments in the developing thymus. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:3371–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000012)30:12<3371::AID-IMMU3371>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ueno T, Hara K, Willis MS, et al. Role for CCR7 ligands in the emigration of newly generated T lymphocytes from the neonatal thymus. Immunity. 2002;16:205–18. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell JJ, Pan J, Butcher EC. Cutting edge: developmental switches in chemokine responses during T cell maturation. J Immunol. 1999;163:2353–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norment AM, Bevan MJ. Role of chemokines in thymocyte development. Semin Immunol. 2000;12:445–55. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellado M, Vila-Coro AJ, Martinez C, Rodriguez-Frade JM. Receptor dimerization: a key step in chemokine signaling. Cell Mol Biol. 2001;47:575–582. (Noisy-le-Grand) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang XF, Wang JF, Matczak E, Proper JA, Groopman JE. Janus kinase 2 is involved in stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha- induced tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins and migration of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2001;97:3342–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Aragay A, et al. The chemokine monocyte chemotactic protein 1 triggers Janus kinase 2 activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of the CCR2B receptor. J Immunol. 1998;161:805–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong M, Uddin S, Majchrzak B, Huynh T, Proudfoot AE, Platanias LC, Fish GN. Rantes activates Jak2 and Jak3 to regulate engagement of multiple signaling pathways in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11427–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010750200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vila-Coro AJ, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Martin De Ana A, Moreno-Ortiz MC, Martinez AC, Mellado M. The chemokine SDF-1alpha triggers CXCR4 receptor dimerization and activates the JAK/STAT pathway. Faseb J. 1999;13:1699–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leonard WJ. Role of Jak kinases and STATs in cytokine signal transduction. Int J Hematol. 2001;73:271–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02981951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imada K, Leonard WJ. The Jak STAT pathway. Mol Immunol. 2000;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(00)00018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Shea JJ, Gadina M, Schreiber RD. Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl.):S121–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomis DC, Gurniak CB, Tivol E, Sharpe AH, Berg LJ. Defects in B lymphocyte maturation and T lymphocyte activation in mice lacking Jak3. Science. 1995;270:794–7. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomis DC, Berg LJ. Peripheral expression of Jak3 is required to maintain T lymphocyte function. J Exp Med. 1997;185:197–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomis DC, Lee W, Berg LJ. T cells from Jak3-deficient mice have intact TCR signaling, but increased apoptosis. J Immunol. 1997;159:4708–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomis DC, Aramburu J, Berg LJ. The Jak family tyrosine kinase Jak3 is required for IL-2 synthesis by naive/resting CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:5411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomis DC, Berg LJ. The role of Jak3 in lymphoid development, activation, and signaling. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:541–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baird AM, Gerstein RM, Berg LJ. The role of cytokine receptor signaling in lymphocyte development. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:157–66. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baird AM, Thomis DC, Berg LJ. T cell development and activation in Jak3-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:669–77. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.6.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheicher C, Mehlig M, Zecher R, Reske K. Dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow: in vitro differentiation using low doses of recombinant granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Immunol Methods. 1992;154:253–64. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Zepeda EA, Rothenberg ME, Ownbey RT, Celestin J, Leder P, Luster AD. Human eotaxin is a specific chemoattractant for eosinophil cells and provides a new mechanism to explain tissue eosinophilia. Nat Med. 1996;2:449–56. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell JJ, Qin S, Bacon KB, Mackay CR, Butcher EC. Biology of chemokine and classical chemoattractant receptors: differential requirements for adhesion-triggering versus chemotactic responses in lymphoid cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:255–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soldevila G, Castellanos C, Malissen M, Berg LJ. Analysis of the individual role of the TCRzeta chain in transgenic mice after conditional activation with chemical inducers of dimerization. Cell Immunol. 2001;214:123–38. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller PYJH, Miserez AR, Dobbie Z. Processing of gene expression data generated by quantitative real-time RT–PCR. Biotechniques. 2002;32:1372–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ikuta K, Weissman IL. Evidence that hematopoietic stem cells express mouse c-kit but do not depend on steel factor for their generation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1502–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:1229–34. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sudbeck EA, Liu XP, Narla RK, Mahajan S, Ghosh S, Mao C, Uckun F. Structure-based design of specific inhibitors of Janus kinase 3 as apoptosis-inducing antileukemic agents. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1569–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellado M, Rodriguez-Frade JM, Manes S, Martinez AC. Chemokine signaling and functional responses: the role of receptor dimerization and TK pathway activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:397–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stein JV, Soriano SF, M'Rini C, et al. CCR7-mediated physiological lymphocyte homing involves activation of a tyrosine kinase pathway. Blood. 2003;101:38–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernandez-Lopez C, Varas A, Sacedon R, Jimenez E, Munoz JJ, Zapata AG, Vicente A. Stromal cell-derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for early human T-cell development. Blood. 2002;99:546–54. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.2.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong MM, Fish EN. Chemokines: attractive mediators of the immune response. Semin Immunol. 2003;15:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1044-5323(02)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baird AM, Lucas JA, Berg LJ. A profound deficiency in thymic progenitor cells in mice lacking Jak3. J Immunol. 2000;165:3680–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.7.3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norment AM, Bogatzki LY, Gantner BN, Bevan MJ. Murine CCR9, a chemokine receptor for thymus-expressed chemokine that is up-regulated following pre-TCR signaling. J Immunol. 2000;164:639–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uehara S, Song K, Farber JM, Love PE. Characterization of CCR9 expression and CCL25/thymus-expressed chemokine responsiveness during T cell development: CD3 (high) CD69+ thymocytes and gammadeltaTCR+ thymocytes preferentially respond to CCL25. J Immunol. 2002;168:134–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carramolino L, Zaballos A, Kremer L, Villares R, Martin P, Ardavin C, Martinez AC, Marquez C. Expression of CCR9 beta-chemokine receptor is modulated in thymocyte differentiation and is selectively maintained in CD8(+) T cells from secondary lymphoid organs. Blood. 2001;97:850–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright DE, Bowman EP, Wagers AJ, Butcher EC, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cells are uniquely selective in their migratory response to chemokines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1145–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Constantin G, Majeed M, Giagulli C, Piccio L, Kim JY, Butcher EC, Laudanna C. Chemokines trigger immediate beta2 integrin affinity and mobility changes: differential regulation and roles in lymphocyte arrest under flow. Immunity. 2000;13:759–69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]