Abstract

The prevalence of food allergic diseases is rising and poses an increasing clinical problem. Peanut allergy affects around 1% of the population and is a common food allergy associated with severe clinical manifestations. The exact route of primary sensitization is unknown although the gastrointestinal immune system is likely to play an important role. Exposure of the gastrointestinal tract to soluble antigens normally leads to a state of antigen-specific systemic hyporesponsiveness (oral tolerance). A deviation from this process is thought to be responsible for food-allergic diseases. In this study, we have developed a murine model to investigate immunoregulatory processes after ingestion of peanut protein and compared this to a model of oral tolerance to chicken egg ovalbumin (OVA). We demonstrate that oral tolerance induction is highly dose dependent and differs for the allergenic proteins peanut and OVA. Tolerance to peanut requires a significantly higher oral dose than tolerance to OVA. Low doses of peanut are more likely to induce oral sensitization and increased production of interleukin-4 and specific immunoglobulin E upon challenge. When tolerance is induced both T helper 1 and 2 responses are suppressed. These results show that oral tolerance to peanut can be induced experimentally but that peanut proteins have a potent sensitizing effect. This model can now be used to define regulatory mechanisms following oral exposure to allergenic proteins on local, mucosal and systemic immunity and to investigate the immunomodulating effects of non-oral routes of allergen exposure on the development of allergic sensitization to peanut and other food allergens.

Keywords: sensitization, oral tolerance, peanut, allergy

Introduction

Oral tolerance is defined as a state of antigen-specific systemic hyporesponsiveness induced by oral exposure to a specific antigen. Oral tolerance can be considered the physiological or default immune response to food antigens; its effectiveness highlighted by the fact that a majority of the population have lifelong clinical and immunological tolerance both to food antigens and to their gut flora.1 However, an increasing incidence of adverse reactions to ingested foods is being reported, which may reflect a failure of oral tolerance induction or a breakdown of its maintenance. Peanuts appear to consist of particular potent allergenic proteins and the prevalence of peanut allergy is rising in both children and adults, making it one of the most common food allergies in the UK and US.2–4 In addition, peanut is more persistent than most other food allergies and accounts for the majority of fatal and near-fatal food-related anaphylaxis in all age groups.5 Immunologically, only immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated Type I allergic reactions are known for certain to play a major role in food allergy.6 However, the mechanisms by which the normal immune system responds to food allergens, and the mechanisms involved in food allergy and/or peanut allergy remains essentially unresolved. Maturity of the animal and the dose of antigen administered is known to play a role in the induction of oral tolerance.1 Babies may be sensitized in utero or by oral exposure to peanut in infancy from breast milk, formula milks made with peanut oil, vitamin supplements and weaning foods that contain peanut or peanut oil with small amounts of peanut protein.

Oral administration of soluble proteins is normally an effective way of inducing specific systemic immunological hyporesponsiveness and several experimental animal models of oral tolerance has been developed. Oral tolerance has been demonstrated after feeding of many different proteins, although the total number of antigens used experimentally is limited, and no model of oral tolerance to peanut proteins has been reported. In addition, most studies investigating oral tolerance use single, highly purified proteins and only few have studied the effects of feeding a mixture of proteins.7 Requirements for tolerance induction may differ for single purified antigens and for the more physiologically relevant exposure to antigenic mixtures. Given the severity and persistence of peanut sensitization the possibility of human testing is limited and potentially dangerous, which highlights the need for the judicious use of animal models to study responses to oral allergens.

In this study, we describe the development of a novel murine model of sensitization and oral tolerance to whole peanut protein extract. Mucosal, local and systemic immune responses to oral and systemic administration of peanut protein were analysed and both the cellular and humoral arm of the immune system explored. Emphasis in the current study is directed to the down-stream effects of gastrointestinal exposure to food allergens, i.e. the response to secondary antigen challenge. We demonstrate that induction of oral tolerance is highly dose dependent and differs for the proteins in peanut and ovalbumin (OVA). Low doses of peanut protein induce sensitization upon secondary challenge. Oral tolerance is shown to be antigen-specific and involves suppression of both T helper 1 (Th1: interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and IgG2a) and Th2 (interleukin-4 (IL-4), IgG1 and IgE) responses while levels of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are enhanced.

Materials and methods

Mice

BALB/c mice were bred and maintained on a special diet free of peanut, OVA, soy and cows' milk. They were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and provided the special diet and water ad libitum. Female mice aged 6–8 weeks were used in this study in accordance with Home Office regulations.

Protein antigens

Partly defatted peanut flour was obtained from the Golden Peanut Company (Alpharetta, GA). A concentrated peanut protein extract was prepared using a modification of the method described by de Jong et al.8 In brief, the flour was defatted with hexane five times and then extracted with 0·1 m NH4HCO3. The supernatant was removed and precipitated with 60% (NH4)2SO4 for 2 hr at 4°. The precipitate was centrifuged, dissolved in a minimum volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and dialysed extensively against PBS. The dialysed peanut extract was filtered through 0·2 µm filters, frozen at −70° and lyophilized. This method uniformly yielded 85–90% pure peanut protein. OVA grade V was purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK).

Oral feeding and immunization procedure

Animals were fed by gavage using a 20-gauge, 30 mm cannula. Each mouse received a single intragastric feed of antigen dissolved in sterile PBS at doses varying from 0·02 mg to 100 mg per mouse (0·001 mg to 5 mg per gram bodyweight). Control mice were sham-fed with PBS. Seven days after the feeding, animals were immunized at the base of the tail with 100 µg of antigen emulsified 1 : 1 with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). Three weeks later animals were given a recall immunization with 100 µg antigen in sterile PBS in the left hind footpad. For analysis of T-cell, cytokine and antibody responses to the immunizing protocol, animals were killed after 1 further week and para-aortic lymph nodes (PLN), mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), spleen and blood was collected.

Delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses in vivo

To elicit an antigen-specific DTH response, mice were challenged 3 weeks after subcutaneous immunization with CFA by injection of 100 µg peanut protein or OVA in PBS into the left hind footpad. Net footpad swelling was measured using a microcalliper (Mitutoyo, Kanagawa, Japan) 24 hr after challenge.

Cell proliferation and cytokine production

Spleen and lymph node cell suspensions were obtained by mechanical disaggregation, and 2 × 105 cells cultured in 96-well flat-bottom plates in a total volume of 200 µl RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 50 µm 2-mercaptoethanol and 5 µg/ml gentamicin. OVA or peanut protein were added at concentrations ranging from 5 to 450 µg/ml. Control responses to the irrelevant antigen (peanut protein or OVA, respectively) at 50 µg/ml or concanavalin A (Con A) at 1 µg/ml were also determined. Cultures were incubated at 37° for 90 hr and pulsed with 1 µCi of [3H]-thymidine (Amersham Pharmacia, Amersham, UK) for the last 16 hr of culture. Cells were harvested and thymidine incorporation determined by liquid scintillation counting on a Trilux MicroBeta (Wallac, Perkin-Elmer, Beaconsfield, UK). Supernatants were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for TGF-β, IL-10, IL-4 and IFN-γ using antibodies from PharMingen (San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Human TGF-β and recombinant mouse IL-10, IL-4 and IFN-γ from PharMingen were used as standards. The detection limit of the assays was 5 pg/ml for IL-4 and 40 pg/ml for TGF-β, IL-10 and IFN-γ.

Antibody responses

At the end of each experiment, mice were bled by cardiac puncture and sera prepared for specific antibody determinations. For antigen-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a antibodies, 96-well Maxosorb plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with peanut or OVA protein at 250 µg/ml in carbonate bicarbonate buffer (CBB) at 4° over night. 100 µl of sera diluted in PBS were added and the plates incubated at 37° for 90 min. After washing, alkaline phosphatase conjugated polyclonal goat anti-mouse IgG Fc (Sigma), rat monoclonal antibody to mouse IgG1 (Zymed, San Francisco, CA) or rat monoclonal antibody to IgG2a (PharMingen) were added for 1 hr at 37°. The alkaline phosphatase substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) (Sigma) was then added and absorbance measured at 405 nm. Total and antigen-specific IgE was measured by an IgE capture method. Maxisorb microtitre plates were coated with 1 µg/ml of rat monoclonal anti-mouse IgE (PharMingen) in CBB at 4° overnight. Optimally diluted experimental sera were added in a volume of 100 µl and incubated at 4° overnight. Following several washes biotin conjugated monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgE (PharMingen) was then added at 1 µg/ml for measurement of total IgE and biotin-conjugated peanut or OVA protein were added at a concentration of 100 µg/ml for measurement of antigen-specific IgE. Plates were incubated for 2 hr at 37°. After washing, alkaline phosphatase streptavidin (PharMingen) was added for 1 hr and the plates developed with pNPP substrate.

Statistical evaluation

The statistical significance of difference between experimental groups in regard to DTH responses, serum antibody levels and cytokine secretion was determined using a two-tailed Student's t-test for unpaired data. Statistical significance in T-cell proliferation between experimental groups over the entire dose–response curve was determined by a two-tailed t-test on the slopes of straight-line fits to the data, equivalent to a one-way anova on two groups. If the slopes were not significantly different, the intercepts were compared also using a two-tailed t-test and equivalent to an analysis of covariance on two groups.9 Differences were regarded as significant when P < 0·05.

Results

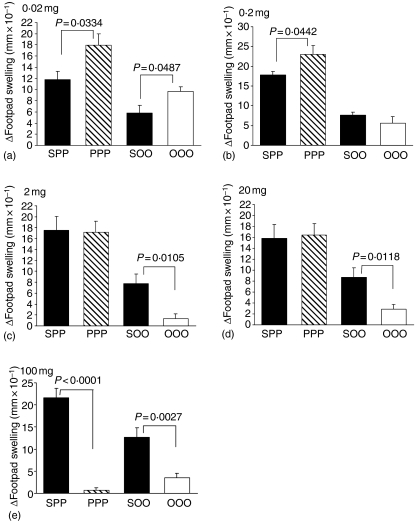

Dose of oral antigen determines priming or suppression of DTH responses upon challenge

DTH responses to peanut protein and OVA were measured as an index of cellular immunity in vivo. Mean DTH responses were significantly enhanced in animals fed either 0·02 mg peanut protein or 0·02 mg OVA compared to their saline-fed controls (Fig. 1a). Animals fed 0·2 mg peanut protein also showed enhanced footpad increments upon peanut challenge that were significantly different from sham-fed animals (Fig. 1b). In contrast, DTH responses in animals fed 0·2 mg OVA was indistinguishable from the saline-fed control group (Fig. 1b). Feeding a dose of 2 mg peanut protein per animal elicited no difference in footpad swelling compared to controls, while a dose of 2 mg OVA induced a significant reduction in the DTH response (Fig. 1c). Increasing the fed dose to 20 mg per animal gave similar results; there was no difference in the DTH response between peanut-fed animals and saline-fed controls, but a significant reduction in the mean footpad increment was induced in animals fed 20 mg OVA (Fig. 1d). At the largest dose of 100 mg antigen, both orally fed peanut protein and OVA significantly reduced the DTH response compared to the saline-fed controls (Fig. 1e).

Figure 1.

DTH response to peanut protein and OVA. Animals were fed peanut protein or OVA at doses of 0·02 mg (a), 0·2 mg (b), 2 mg (c), 20 mg (d) or 100 mg (e) and DTH responses were measured following immunizations. Results are expressed as mean footpad increment + 1 SEM (n ≥ 6). Individual experiments were repeated between 2 and 10 times with similar results. SPP: saline-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; PPP: peanut-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; SOO: saline-fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA; OOO: OVA fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA.

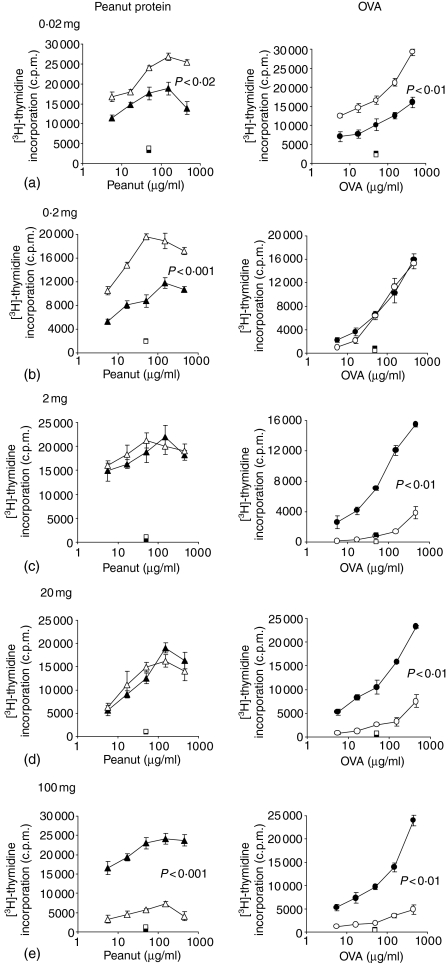

Oral antigen dose effects cell proliferation following immunization with CFA

Antigen-specific proliferation by cells from PLN draining the tailbase immunization site, MLN draining the gut and from the spleen were measured by incorporation of [3H]-thymidine.

High levels of antigen-specific proliferation were seen in cells from PLN after a saline feed and peanut protein or OVA immunization with CFA and recall immunization. A feed of 0·02 mg peanut protein or OVA prior to this immunization further significantly enhanced the antigen-specific cell proliferation compared to the saline-fed controls (Fig. 2a). Proliferation was similarly significantly elevated after a feed of 0·2 mg of peanut protein per animal, but proliferation of cells from animals fed 0·2 mg OVA was equivalent to saline-fed controls (Fig. 2b). Proliferation by PLN cells from animals fed 2 mg peanut protein was no different from control animals, whereas proliferation of cells from animals fed 2 mg of OVA was significantly reduced compared to the saline-fed animals (Fig. 2c). A very similar pattern was seen at the next dose of 20 mg peanut protein or OVA fed per animal. PLN cells from peanut-fed animals proliferated strongly and equally to the saline-fed controls, while OVA fed animals displayed a highly significant reduction in antigen-specific cell proliferation (Fig. 2d). Feeding 100 mg peanut protein per animal resulted in a significant reduction of the proliferative response to peanut and a near total abrogation of [3H]-thymidine incorporation compared to saline-fed controls (Fig. 2e). Feeding 100 mg OVA per animal also resulted in a profound reduction of the specific cell proliferation (Fig. 2e), in the same way to that observed after feeding 2 mg or 20 mg of OVA.

Figure 2.

Antigen-specific T-cell proliferation. Peanut-specific (left column) and OVA-specific (right column) proliferation by PLN T cells were measured from animals fed peanut protein or OVA at doses of 0·02 mg (a), 0·2 mg (b), 2 mg (c), 20 mg (d) or 100 mg (e) prior to tailbase immunization with peanut protein or OVA in CFA and challenge. Specific T-cell proliferation was measured after 90 hr in vitro reactivation with peanut or OVA. Cells were pooled from n ≥ 6 mice per group and results are expressed as the mean c.p.m. of triplicate cultures ± 1 SEM. Background proliferation when no antigen was present has been subtracted. Squares represent proliferation to a control antigen. All groups proliferated with similar c.p.m. to the mitogen Con A. Individual experiments were repeated between 2 and 10 times with near identical results. ▴: Saline-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; ▵: peanut-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; •: saline-fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA; ○: OVA fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA.

Similar proliferative patterns as shown by cells from PLN in Fig. 2 were observed with cells from MLN and from the spleen, although the response by MLN cells was routinely lower (results not shown). This suggests that the enhanced or reduced level of antigen-driven cell proliferation observed following feeding of specific doses of antigen was a systemic phenomenon. No significant proliferation was observed to an irrelevant control antigen in any group, but all groups proliferated strongly and equally to the mitogen Con A (data not shown).

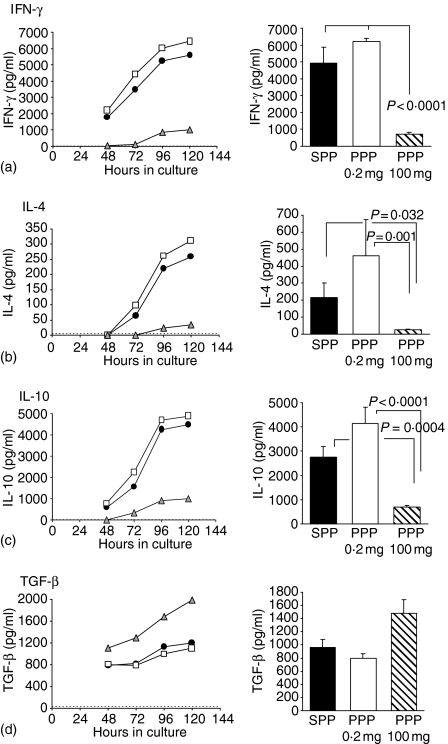

Dose of oral peanut protein alters the cytokine profile of antigen-specific T cells

The effect of feeding a priming or a tolerogenic dose of peanut protein on cytokine production by T cells from PLN, MLN and spleen were measured by reactivating 2 × 106 cells with either peanut protein, control antigen (OVA) or Con A in vitro for 24–168 hr.

PLN T cells from animals fed 0·2 mg peanut protein or sham-fed saline prior to immunization with peanut protein in CFA and recall immunization with peanut protein produced and secreted large amounts of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 upon reactivation with peanut protein in vitro. PLN T cells from the animals fed 0·2 mg peanut protein consistently secreted slightly higher amounts of both IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 than the saline-fed controls, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 3a). In contrast, animals initially fed 100 mg of peanut protein showed significantly reduced IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 production by PLN T cells compared to the saline-fed controls and to the animals fed 0·2 mg peanut protein (Fig. 3a). TGF-β production by PLN T cells showed a reverse pattern from that of the other cytokines in relation to the initial oral dose of peanut protein. PLN T cells from animals fed saline or 0·2 mg peanut protein secreted approximately 800–900 pg TGF-β/ml, while a feed of 100 mg peanut protein resulted in TGF-β levels of around 1500 pg/ml after 96 hr stimulation with peanut protein in vitro (Fig. 3d). The increase in TGF-β secretion following a 100 mg peanut-protein feed was, however, not statistically significant (P =0·071), but this tendency of increased TGF-β production was observed in every experiment (n = 4).

Figure 3.

Peanut-specific IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10 and TGF-β secretion. IFN-γ (a), IL-4 (b), IL-10 (c) and TGF-β (d) production by PLN T cells from animals fed saline, 0·2 mg peanut protein or 100 mg peanut protein followed by immunization with peanut protein in CFA and challenge with peanut. Cytokine production was analysed following reactivation with peanut protein in vitro between 24 and 120 hr (left column) or routinely for 96 hr (right column). Cells were pooled from n ≥ 6 mice per group and analysed in triplicate. Results are expressed as the mean cytokine secretion + 1 SEM of two (PPP 0·2 mg) to seven (four for TGF-β) (SPP and PPP 100 mg) individual experiments. The horizontal dashed line indicates the limit of detection for the cytokine assays, though this is close to the x-axis in (a, c). None of the cytokines were released in response to a control antigen or when cells were not reactivated. SPP (•): Saline-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; PPP 0·2 mg (□): Fed 0·2 mg peanut, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; PPP 100 mg (▵): Fed 100 mg peanut, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut.

The kinetics of the cytokine production and release were similar for the 0·2 mg peanut-protein fed groups, the saline-fed groups and the 100 mg peanut-protein fed groups; only the amount of secreted cytokine seemed to differ between the groups (Fig. 3 left column). All cytokines increased in the supernatant over time and plateaued between 96 and 120 hr. Similar results to those shown in Fig. 3 were obtained from splenocytes. The patterns of cytokine secretion between the 0·2 mg peanut-fed groups, the saline-fed groups and the 100 mg peanut-fed groups were identical, but the overall amounts of cytokines were slightly lower. Cytokine secretion by MLN cells was negligible (data not shown).

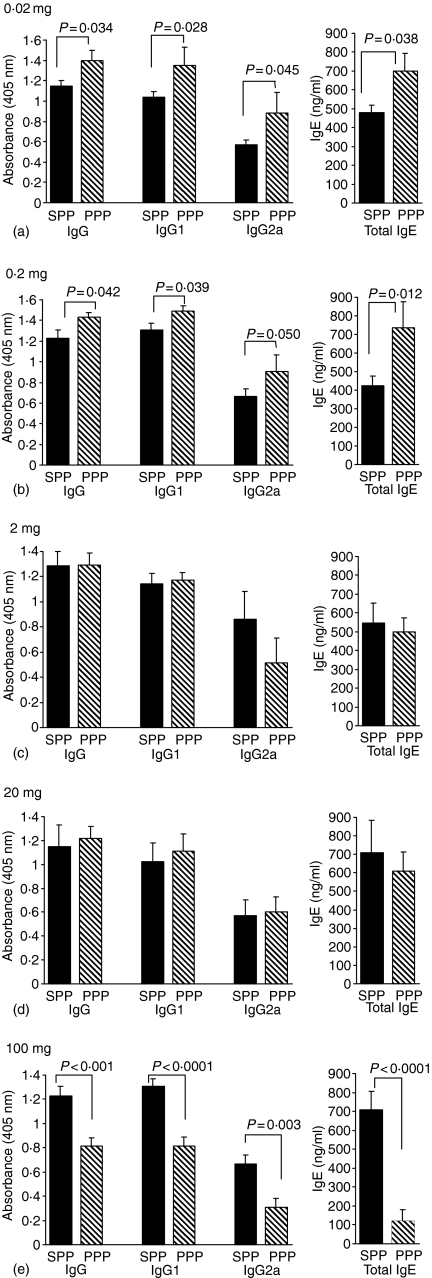

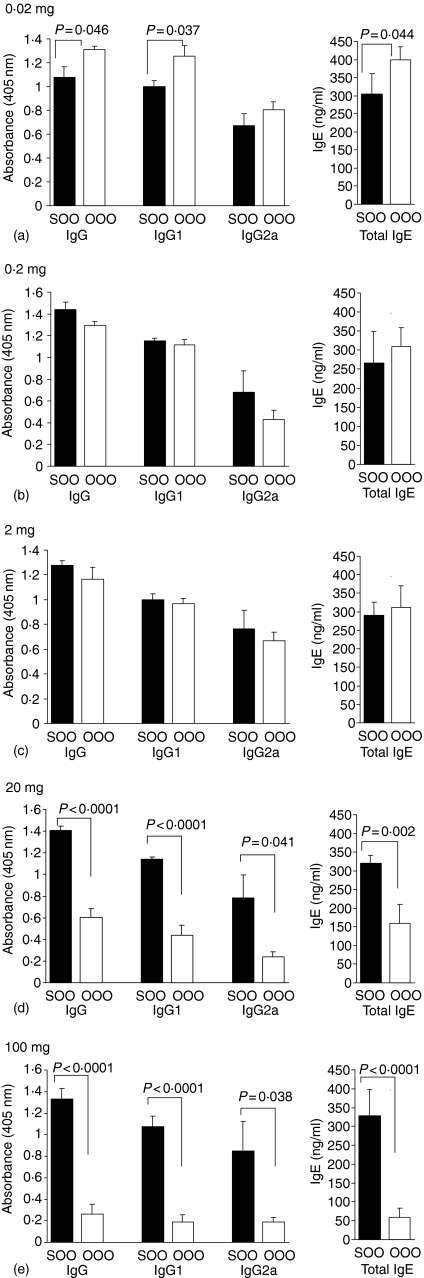

Dose of oral antigen determines the level of induced specific antibody responses following antigen challenge

Experimental animals fed saline prior to immunization with peanut protein or OVA in CFA and challenge with peanut protein or OVA gave strong antigen-specific antibody responses of IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and high levels of total IgE. A feed of 0·02 mg peanut protein per animal prior to an identical immunization protocol enhanced the antibody response with a significant increase of peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and of total IgE (Fig. 4a). An oral dose of 0·02 mg OVA significantly enhanced the OVA-specific IgG, IgG1 and total IgE levels, but no difference in the level of OVA-specific IgG2a was seen compared to the saline-fed controls (Fig. 5a). Feeding a larger dose of 0·2 mg peanut protein resulted in similar antibody levels as observed after the 0·02 mg dose. The levels of peanut-specific IgG immunoglobulins were significantly enhanced compared to the saline-fed controls and the level of total IgE in the serum was also significantly elevated (Fig. 4b). A feed of 0·2 mg OVA made no difference to the levels of OVA-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a or total IgE (Fig. 5b).

Figure 4.

Antibody response to peanut. Peanut-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a as well as total IgE were measured in serum from animals fed peanut protein at doses of 0·02 mg (a), 0·2 mg (b), 2 mg (c), 20 mg (d) and 100 mg (e) prior to immunizations with peanut protein. Sera were diluted 1000 times for peanut-specific IgG and IgG1, 200 times for IgG2a and 10 times for total IgE measurements. Results are expressed as mean antibody levels + 1 SEM of n ≥ 6 animals per group. The individual experiments were repeated between 2 and 10 times with identical antibody patterns between the saline- and peanut-fed groups. SPP: saline-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut; PPP: peanut-fed, immunized with peanut in CFA, challenged with peanut.

Figure 5.

Antibody response to OVA. OVA-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a as well as total IgE were measured in serum from animals fed OVA at doses of 0·02 mg (a), 0·2 mg (b), 2 mg (c), 20 mg (d) and 100 mg (e) prior to immunizations with OVA. Sera were diluted 1000 times for OVA-specific IgG and IgG1, 200 times for IgG2a and 10 times for total IgE measurements. Results are expressed as the mean antibody levels + 1 SEM of n ≥ 6 animals per group. The individual experiments were repeated between one and three times with similar results. SOO: saline-fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA; OOO: OVA fed, immunized with OVA in CFA, challenged with OVA.

An oral dose of 2 mg or 20 mg peanut protein induced no difference in levels of either peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a or total IgE between the peanut-fed groups and the saline-fed control groups (Fig. 4c, d). Specific antibody levels after feeding of 2 mg of OVA were also indistinguishable from controls. In contrast, feeding 20 mg of OVA per animal significantly reduced both OVA-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and total IgE production (Fig. 5c, d). Feeding the highest oral dose of 100 mg peanut protein per animal resulted in a highly statistical significant reduction of both peanut-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a as well as a reduction of total IgE levels compared to the saline-fed control animals (Fig. 4e). Similarly, a feed of 100 mg OVA per animal resulted in an inhibited OVA-specific IgG antibody response as well as a reduction of total IgE (Fig. 5e).

In most experiments the level of antigen-specific IgE was also determined. The patterns of antigen-specific IgE responses were similar to those shown for total IgE (data not shown). Naïve mouse serum from BALB/c mice of the same colony tested negative for peanut- or OVA-specific IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a immunoglobulins as well as peanut- or OVA-specific IgE in all assays (data not shown). The levels of total IgE in serum of naïve mice were below the 4 ng/ml detection limit of the total IgE assay.

By comparing the oral dose–response relationship for the cellular and the humoral responses in Figs 2 and 5 it could be noted that at an intermediate dose of 2 mg OVA fed per animal, the proliferative cellular response was inhibited but the level of OVA-specific IgG was not. These data suggest that a higher oral dose is needed to inhibit antibody synthesis than to inhibit specific T-cell proliferation.

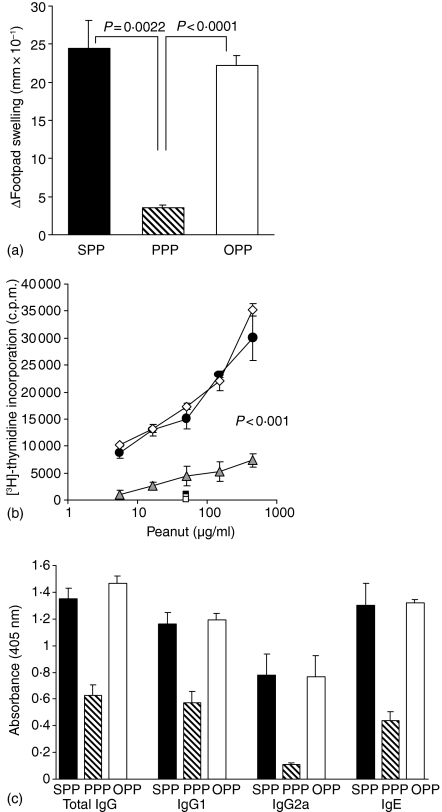

Induction of oral tolerance to peanut is antigen specific

In the present model of oral tolerance to peanut protein it was observed that in the effector phase, no T-cell proliferation or cytokine production occurred when cells were reactivated with a control antigen (OVA). This indicated antigen specificity at the effector phase, but whether the induction of oral tolerance to peanut protein could be induced by feeding high doses of any protein remained unanswered. To address this question animals were fed either saline, 100 mg peanut protein or 100 mg OVA by intragastric gavage prior to identical immunizations with peanut in CFA and challenge with peanut.

Animals fed either saline or OVA prior to peanut protein immunization mounted a strong DTH response to peanut protein as demonstrated by mean footpad increments of 24·4 and 22·2 (mm × 10−1), respectively. In contrast, animals fed peanut protein did not mount a DTH response and mean footpad swellings were significantly reduced compared to both the saline-fed and the OVA-fed group (Fig. 6a). A similar pattern was demonstrated when peanut-specific T-cell proliferation was measured in PLN and spleen cells. PLN T cells from saline-fed and OVA-fed animals proliferated vigorously to reactivation with peanut protein in vitro, while the response by T cells from peanut-fed animals was significantly lower than both the saline-fed and the OVA-fed animals (P < 0·001) (Fig. 6b). Similar results were obtained with splenocytes (results not shown). Additionally, PLN cells from animals fed saline or OVA and immunized with peanut protein produced large and equal amounts of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 but little TGF-β on in vitro stimulation with peanut. Conversely, PLN cells from animals fed 100 mg peanut protein prior to peanut immunizations produced much lower levels of both IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 compared to the saline- or OVA-fed groups but they produced higher levels of TGF-β (results not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of feeding peanut protein or OVA on subsequent peanut-specific responses. Animals (n = 6/group) were fed saline, 100 mg peanut protein or 100 mg OVA prior to immunization with peanut protein in CFA and challenge with peanut. (a) DTH responses 24 hr after challenge in the footpad. Results are expressed as the mean footpad increments + 1 SEM. (b) Peanut-specific T-cell proliferation in PLN cell cultures after 90 hr in vitro reactivation with peanut protein. Cells were pooled from six mice per group and results are expressed as the mean c.p.m. of triplicate culture ± 1 SEM. Background proliferation without antigen has been subtracted. Squares show proliferation to a control antigen. All groups proliferated with similar (c.p.m.) to Con A stimulation. (c) Peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and IgE levels in serum 7 days after challenge. Sera were diluted 1000 times for IgG and IgG1, 200 times for IgG2a and 10 times for IgE measurements. Results are expressed as the mean antibody levels + 1 SEM of six individual animals per group. SPP (•): Saline-fed, peanut immunized and peanut challenged; PPP (▵): Peanut-fed, peanut immunized and peanut challenged; OPP (◊): OVA fed, peanut immunized and peanut challenged.

High levels of peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and IgE were detected in serum from animals fed either saline or OVA prior to peanut protein immunizations, but as expected feeding 100 mg peanut protein prior to similar immunization inhibited the antibody response to peanut (Fig. 6c). Feeding OVA had no effect on the peanut antibody response and there were no significant differences in the levels of peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a or IgE between the saline- and OVA-fed groups. In contrast, levels of peanut-specific IgG, IgG1, IgG2a and IgE were all significantly reduced in animals fed peanut protein compared to both saline- and OVA-fed animals (all P < 0·01 and in most cases P < 0·0001). In all experimental groups, total IgE levels in serum closely matched levels of peanut-specific IgE (results not shown).

Taken together, the above experiments (Fig. 6) show that feeding 100 mg OVA prior to immunization with peanut protein has no effect on T- or B-cell responses to peanut. Only when animals were fed 100 mg peanut protein was tolerance to peanut observed. This suggests that the induction of oral tolerance is antigen specific.

Discussion

We present a novel model of sensitization and oral tolerance to peanut protein and report the characterization of induced cellular and humoral responses. The induction of oral tolerance with single feeds is shown to be highly dose dependent. Systemic hyporesponsiveness to peanut protein was only successfully induced by feeding a ‘high dose’ of 100 mg peanut protein per animal. Oral administration of 20 mg or 2 mg peanut protein, which are commonly reported tolerizing doses, did not induce tolerance. Gastrointestinal exposure to 0·2 mg or 0·02 mg peanut protein induced significant priming upon secondary peanut challenge. Both orally induced hypo- and hyper-responsiveness were antigen specific in the effector phase as suggested by the fact that cell proliferation and cytokine production were only observed in response to stimulation with peanut protein and not to the control antigen OVA. Furthermore, the induction of oral tolerance to peanut protein was also shown to be antigen specific as feeding of 100 mg OVA prior to peanut protein immunization did not attenuate the response to a subsequent challenge with peanut. Only feeding of peanut protein suppressed specific DTH responses, cell proliferation, cytokine responses and immunoglobulin synthesis. Our model of oral tolerance to peanut protein thus appear to be antigen specific, which confirms findings from other models of oral tolerance10 and the general consensus that oral tolerance is specific to the fed antigen.1,11

Oral administration of 100 mg peanut protein extract significantly suppressed responses of both the cellular and the humoral arm of the immune response but did not completely abolish it. Peanut-specific cell proliferation was significantly reduced, while the overall cell proliferative capacity remained unaffected as demonstrated by vigorous responses to Con A. Peanut-induced secretion of IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 was also significantly reduced in fed animals. In contrast, secretion of TGF-β was consistently enhanced although it did not reach statistically significant levels compared to controls (P = 0·071). This may be a result of limited number of animals (n = 24) undergoing TGF-β analysis (n = 4 experiments) or it may be that TGF-β does not play a significant role in the maintenance of tolerance to peanut. The role of TGF-β in the induction and/or maintenance of oral tolerance has been much debated, with many reports suggesting an important role for TGF-β12,13 whereas others find no evidence of TGF-β involvement in oral tolerance.14 IL-10 is additionally an important immuoregulatory cytokine, which has been implicated in peripheral tolerance to the normal intestinal flora in the severe combined immunodeficiency inflammatory bowel disease model15,16 and the induction of low-dose oral tolerance to autoantigens.12 IL-10 does not appear to be directly involved in the maintenance or effector phase of tolerance to peanut protein, which supports findings in other models of oral tolerance to OVA.17 An obligatory role of IL-10 in the induction of oral tolerance is also uncertain as oral tolerance can be induced in IL-10−/− mice.18

Oral administration of 100 mg peanut protein had a significant effect on antibody production. It reduced the level of peanut-specific IgG and IgE, as well as the IgG subclasses IgG1 and IgG2a. Levels of all peanut-specific antibodies were decreased with no Th1 or Th2 bias, which was consistent with the decrease in the production of both IFN-γ and IL-4 and IL-10. When oral tolerance to peanut protein was successfully induced it thus suppressed both Th1 and Th2 responses, and does therefore not support the notion that feeding antigen preferentially suppresses Th1 responses.19 Similar conclusions as presented here have been reached in models of oral tolerance to OVA where both Th1 and Th2 type responses were suppressed.17

In peanut-sensitive animals, most of the proteins in peanut evoked specific IgG binding, although the highest level of specific IgG-binding to known allergenic peanut proteins was shown for Ara h1 and Ara h2, as demonstrated by immunoblotting techniques (data not shown). Sera from all peanut-sensitive mice showed antibody binding to these major allergenic proteins, which are recognized by over 95% of human peanut allergic subjects.20,21 Food-specific IgG antibodies are also found in healthy human subjects22,23 where they may participate in the safe clearance of circulating food antigens. The relevance of food-specific IgG antibodies in allergy and whether a high level of specific IgG or specific IgG with an abnormal epitope-recognition pattern can induce immune pathology remains unknown. IgE-mediated reactions are the only mechanisms known for certain to play a major role in food allergy6 and so it was of interest that induction of oral tolerance to peanut in the present mouse model significantly reduced the induction of total and peanut-specific IgE.

Primary sensitization to protein allergens is clearly a key step in the pathogenesis of food allergic diseases. It is unknown whether primary systemic sensitization to food allergens occurs through gastrointestinal exposure or via other routes. Gastrointestinal exposure to soluble protein antigens is a powerful way to induce systemic hyporesponsiveness, but as shown here, primary oral exposure to protein antigens does not always lead to tolerance. Oral administration of peanut protein in doses of 0·2 mg or 0·02 mg induced systemic hyperresponsiveness upon re-exposure to peanut protein. This supports the notion that small doses of orally administered antigen can prime an animal for subsequent systemic and local responses, as shown for oral administration of OVA.24 Oral doses of either 0·2 mg or 0·02 mg peanut protein significantly enhanced peanut-specific cell proliferation, without affecting the proliferation to mitogenic stimuli such as Con A. Enhanced secretion of the cytokines IFN-γ, IL-4 and IL-10, but reduced production of TGF-β, was shown from PLN and spleen cells from animals fed these sensitizing doses of peanut protein. Analysing the antibody response in individual animals fed either 0·2 mg or 0·02 mg peanut protein demonstrated significantly elevated levels of peanut-specific IgG and IgE antibodies. The observation that oral exposure to small amounts of peanut protein enhances IL-4 secretion and significantly raises levels of peanut-specific IgE upon re-exposure to peanut may be of clinical relevance in explaining primary allergic sensitization. Control animals used in this study were made hypersensitive to peanut protein by subcutaneous immunization with peanut protein in CFA and recall immunization with peanut. The additional priming of animals through feeding of small doses of peanut protein highlights the powerful immunoregulatory effects gastrointestinal exposure to protein antigens has on systemic immunity.

The immunochemical and physiochemical properties that account for a proteins allergenicity are poorly understood, but the nature of the antigen is clearly important for the induction of tolerance11,25 and in directing the Th1/Th2 deviation.26 This study permitted a direct comparison between responses following oral administration of peanut protein and OVA. Results showed that approximately 50-fold larger doses of peanut protein compared with OVA were required to induce suppression of specific T-cell responses. This observation may not solely be explained by the peanut extract being a mixture of many proteins with concentrations of any given protein below that of the single OVA protein when administered. Immunoblots demonstrated that sensitized mice in the present model mainly reacted to Ara h1 and Ara h2, which in a quantitative analysis of different peanut varieties around the world were found to account for between 12 and 16% and 5·9–9·3% of the total protein content, respectively.27 If directly compared on a weight to weight basis, induction of tolerance to Ara h1 should thus only require between six and eight times higher dose than that of the purified OVA. The different dose requirements for peanut and OVA in the induction of oral tolerance may reflect differential immune mechanisms for the induction of tolerance to individual antigens and to antigenic mixtures, or may reflect differences in immunogenicity of OVA and peanut. The present study demonstrates that peanut protein has a potent sensitizing effect and primes animals for a subsequent exposure more readily and at higher doses than OVA. Peanut protein reproducibly caused larger DTH responses than OVA and sensitized animals showed vigorous specific cell proliferation at lower doses of peanut protein and with a steeper dose–response slope than animals sensitized to OVA. This suggests that peanut proteins may be more immunogenic (or allergenic) than OVA and that peanut protein may induce hypersensitivity more effectively. It might also suggest that some proteins in the peanut protein mixture may have direct immunomodulatory or stimulatory effects. The sensitizing effect of peanut proteins was similarly shown in a murine model of cholera toxin-induced peanut anaphylaxis, where sensitization to peanut protein required fewer doses and a shorter sensitizing period than sensitization to cows milk.28 These conclusions reflect findings in human food-allergic subjects and strongly suggests that the nature of the antigen plays an important role in determining the immunological outcome of an allergen encounter.

The developed model of sensitization and oral tolerance to peanut protein presented here demonstrates that tolerance to peanut can be successfully induced experimentally, but that gastrointestinal exposure to peanut protein can also initiate potent sensitization with high levels of IL-4 and specific IgE. This sensitization was initiated solely through gastrointestinal mucosal exposure without the use of additional adjuvants. The described model can now be used to further define the regulation of specific immune responses following intestinal mucosal exposure of proteins with different allergenic potential. It is additionally well suited to explore the modulatory effects of concomitant non-oral routes of peanut exposure on the development of systemic tolerance or allergic sensitization to peanut and other allergens.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Dominique Maffre for technical laboratory assistance.

This work was supported by the Food Standards Agency (T07022).

Research at the Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children National Health Service (NHS) Trust benefits from research and development funding received from the UK NHS Executive.

References

- 1.Strobel S, Mowat AM. Immune responses to dietary antigens: oral tolerance. Immunol Today. 1998;19:173–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1203–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)02026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kagan RS, Joseph L, Dufresne C, Gray-Donald K, Turnbull E, Pierre YS, Clarke AE. Prevalence of peanut allergy in primary-school children in Montreal, Canada. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:1223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grundy J, Matthews S, Bateman B, Dean T, Arshad SH. Rising prevalence of allergy to peanut in children: Data from 2 sequential cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:784–9. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.128802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bock SA, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Fatalities due to anaphylactic reactions to foods. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:191–3. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruijnzeel-Koomen C, Ortolani C, Aas K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Bjorksten B, Moneret-Vautrin D, Wuthrich B. Adverse reactions to food. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology Subcommittee. Allergy. 1995;50:623–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1995.tb02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Afuwape AO, Turner MW, Strobel S. Oral administration of bovine whey proteins to mice elicits opposing immunoregulatory responses and is adjuvant dependent. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:40–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jong de E, Spanhaak S, Martens BP, Kapsenberg ML, Penninks AH, Wierenga EA. Food allergen (peanut)-specific TH2 clones generated from the peripheral blood of a patient with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armitage P, editor. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. Oxford: Blackwell; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SD, Hanson DG. Inhibition of specific immune responses by feeding protein antigens. IV. Evidence for tolerance and specific active suppression of cell-mediated immune responses to ovalbumin. J Immunol. 1979;123:2344–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer L. Oral tolerance: new approaches, new problems. Clin Immunol. 2000;94:1–8. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Kuchroo VK, Inobe J, Hafler DA, Weiner HL. Regulatory T cell clones induced by oral tolerance: suppression of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science. 1994;265:1237–40. doi: 10.1126/science.7520605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Inobe J, Marks R, Gonnella P, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. Peripheral deletion of antigen-reactive T cells in oral tolerance. Nature. 1995;376:177–80. doi: 10.1038/376177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KM, Eaton AD, Finlayson LM, Garside P. Oral tolerance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:S175–S78. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.supplement_3.15tac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powrie F, Carlino J, Leach MW, Mauze S, Coffman RL. A critical role for transforming growth factor-beta but not interleukin 4 in the suppression of T helper type 1-mediated colitis by CD45RB (low) CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2669–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asseman C, Mauze S, Leach MW, Coffman RL, Powrie F. An essential role for interleukin 10 in the function of regulatory T cells that inhibit intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 1999;190:995–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garside P, Steel M, Worthey EA, Satoskar A, Alexander J, Bluethmann H, Liew FY, Mowat AM. T helper 2 cells are subject to high dose oral tolerance and are not essential for its induction. J Immunol. 1995;154:5649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aroeira LS, Cardillo F, De Albuquerque DA, Vaz NM, Mengel J. Anti-IL-10 treatment does not block either the induction or the maintenance of orally induced tolerance to OVA. Scand J Immunol. 1995;41:319–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1995.tb03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melamed D, Friedman A. In vivo tolerization of Th1 lymphocytes following a single feeding with ovalbumin: anergy in the absence of suppression. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1974–81. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burks AW, Williams LW, Helm RM, Connaughton C, Cockrell G, O'Brien T. Identification of a major peanut allergen, Ara h I, in patients with atopic dermatitis and positive peanut challenges. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;88:172–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90325-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burks AW, Williams LW, Connaughton C, Cockrell G, O'Brien TJ, Helm RM. Identification and characterization of a second major peanut allergen, Ara h II, with use of the sera of patients with atopic dermatitis and positive peanut challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;90:962–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90469-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freed DLJ, Waickman FJ. laboratory diagnosis of food intolerance. In: Brostoff J, Challacombe SJ, editors. Food Allergy and Intolerance. London: Saunders; 2002. pp. 837–56. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolopp-Sarda MN, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Gobert B, Kanny G, Guerin L, Faure GC, Bene MC. Polyisotypic antipeanut-specific humoral responses in peanut-allergic individuals. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mowat AM. The regulation of immune responses to dietary protein antigens. Immunol Today. 1987;8:93–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(87)90853-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald TT. T cell immunity to oral allergens. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:620–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Racioppi L, Ronchese F, Matis LA, Germain RN. Peptide-major histocompatibility complex class II complexes with mixed agonist/antagonist properties provide evidence for ligand-related differences in T cell receptor-dependent intracellular signaling. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1047–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.4.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koppelman SJ, Vlooswijk RA, Knippels LM, Hessing M, Knol EF, van Reijsen FC, Bruijnzeel-koomen CA. Quantification of major peanut allergens Ara h 1 and Ara h 2 in the peanut varieties Runner, Spanish, Virginia, and Valencia, bred in different parts of the world. Allergy. 2001;56:132–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.056002132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li XM, Serebrisky D, Lee SY, et al. A murine model of peanut anaphylaxis: T- and B-cell responses to a major peanut allergen mimic human responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:150–8. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.107395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]