Abstract

Recent characterization of the thrombin receptor indicates that it plays a role in T-cell signalling pathways. However, little is known regarding the signalling events following stimulation of additional members of the protease-activated receptor (PAR) family, i.e. PAR2 and PAR3. Most of the postligand cascades are largely unknown. Here, we illustrate that in Jurkat T-leukaemic cells, activation of PAR1, PAR2 and PAR3 induce tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1. This response was impaired in Jurkat T cells deficient in p56lck (JCaM1.6). Activation of PARs also led to an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 and SLP-76, two key proteins in T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling. We also demonstrated that p56lck is meaningful for integrin signalling. Thus, JCaM1.6 cells exhibited a marked reduction in their adherence to fibronectin-coated plates, as compared to the level of adherence of Jurkat T cells. While the phosphorylation of Vav1 in T cells is augmented following adhesion, no additional increase was noted following treatment of the adhered cells with PARs. Altogether, we have identified key components in the postligand-signalling cascade of PARs and integrins. Furthermore, we have identified Lck as a critical and possibly upstream component of PAR-induced Vav1 phosphorylation, as well as integrin activation, in Jurkat T cells.

Introduction

Serine proteases, traditionally considered to participate principally in the degradation of cellular proteins, are also known to be signalling molecules that regulate cellular functions by activating specific cell-surface receptors.1,2 The protease-activated receptors (PARs), a recently established class of protease receptors belonging to the G-coupled seven-transmembrane domain family, have a unique mode of activation. PARs are activated by the enzymatic digestion of their N-terminal extracellular portion that exposes an internal ligand unique for each receptor.1,2 Unlike the activation of most cellular growth factor receptors, activation of PARs does not require the traditional ligand–receptor complex formation. Instead, PARs serve as substrates for proteolytic digestion that results in an irreversible form of the activated protein which transduces further cell signalling.3 The seven-transmembrane G-coupled thrombin receptor (PAR1) is the first known example of this family. Cleavage of the Arg 41–Ser 42 residues of the N-terminal extracellular portion of PAR1 unmasks an internal ligand that binds intramolecularly to the second transmembrane loop of the receptor. Thus, PAR1 is a polypeptide receptor that contains its own internal ligand (SFLLRN). To date, four such cleavable receptors have been described (PAR1 to PAR4). Of the four such cleavable receptors, three (PAR1, PAR3 and PAR4) are cleaved by thrombin and are therefore considered to be ‘thrombin receptors’.1–5 In contrast, PAR2 is known to be activated by tryptase and trypsin from mast cells, as well as by the coagulation factors VIIa and Xa, but not by thrombin.6,7 It is postulated, but not yet proven, that the PAR family system may simply provide redundancy in a pathway important to the regulation of various biological processes such as adhesion and migration.

The signalling pathways of PARs remain enigmatic; however, several key proteins shown to participate in tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor-mediated cascades have also been shown to contribute to PAR signalling.8 The signal transducer Vav1 is a protein that may potentially participate in processes mediated by PARs. Although initially identified as an oncogene,9 results found over the past several years suggest that Vav1 is an important signal transducer protein, with a pivotal role in haematopoietic cell activation.10,11 Vav1 is a complex and unique modular protein.10,11 In fact, no other protein or protein family contains such an intricate motif structure. These motifs include: a dbl homology domain (DH) that activates GTP-bound proteins of the Rho-like family of proteins; a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain; and a Src homology 2 (SH2) and two Src homology 3 domains (SH3).

Vav1 is expressed exclusively in haematopoietic cells9 where it is tyrosine phosphorylated following activation by several cytokines, growth factors or antigen receptors.10–13 Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 regulates its activity as a guanine-nucleotide exchange factor for the Rho-like small GTPases RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42, which lead to cytoskeletal reorganization and activation of stress-activated protein kinases (SAPK/JNKs).14

Given the complexity of the Vav1 protein, its restricted expression pattern and its involvement in various signalling cascades, it is not surprising that Vav1 has been found to play a critical role in T-cell signalling. Mice deficient in Vav1 exhibit numerous defective responses to T-cell stimulation, including capping of the T-cell receptor (TCR) following its activation, recruitment of the actin cytoskeleton to the CD3ζ chain of the TCR, interleukin-2 (IL-2) production and proliferation, cell cycle progression, activity of nuclear factor (NF)-ATc, phosphorylation of SLP-76 and increase in Ca2+ influx.15,16 Thus, in T cells, Vav1 integrates signals from lymphocyte antigen receptors and costimulatory receptors to control numerous immune functions, as well as T-cell development, differentiation and cell cycle control.

Recent characterization of the thrombin receptor indicates that it plays a role in T-cell signalling pathways.8 However, there is very little information available regarding PAR2- and PAR3-mediated signalling processes.4–7 Thus, we wondered whether Vav1, a haematopoietic signal transducer protein, might play a critical role in PAR-induced processes in T cells, similar to its hypercritical role in TCR-induced processes.15,16 Here we clearly show that activation of several PAR members induces tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in Jurkat T-leukaemic cells. As we did not observe this reaction when we used Jurkat T cells deficient in p56lck (JCaM1.6), we concluded that tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in response to PAR stimulation is dependent on p56lck. PAR activation led also to an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 and SLP-76, two key proteins in TCR signalling. Lck is critical also in Jurkat T-cell integrin activation. Our results suggest that Lck and Vav1 also play a significant role in the cellular adherence to the fibronectin (FN) substratum. Although Jurkat T cells adhered substantially to FN-coated plates, JCaM1.6 cells failed to do so. This difference was also reflected by the Vav1 phosphorylation pattern in T cells following adhesion.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Jurkat T cells, JCam1.6 cells and JCam1.6 cells reconstituted with Lck (JCaM/Lck) were grown in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in 1% Triton-X-100 lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated for 1–5 hr with the indicated antibodies. The resulting immune complexes were harvested with protein A–sepharose beads (Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ) and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose and immunoblotted with the antibodies described below. Blots were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Pierce) followed by autoradiography, as described previously.12

Immobilization of bacterial fusion proteins on glutathione sepharose beads

Fusion proteins were purified from transformed Escherichia coli bacteria that had been stimulated with isopropyl-β-d-thio-galactopyranoside (IPTG) at a concentration of 0·3 µm. After 2 hr of additional growth, bacteria were lysed by sonication in a solution containing 10 mm Tris–HCl (pH 8·0); 0·5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 100 mm sodium chloride, 20 mm EDTA (pH 8·0), and protease inhibitors. Lysed bacteria were spun at 4° for 15 min, and the supernatant was then immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads (Pharmacia). Bound proteins were washed three times in lysis buffer, and then used in the various binding assays.12 Cell lysates were incubated with the appropriate fusion proteins immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads (5 µg), as described previously.12 The bound proteins were washed three times with HNTG (20 mm HEPES, pH 7·5, 150 mm NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0·5% SDS and 10% glycerol), resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies (Abs). Blots were detected by ECL (Pierce), as described above.

Activation of Jurkat T cells

Jurkat T cells at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/100 µl were activated with the anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb) OKT3 (1 : 100; American Type Tissue Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) at 37° for 1 min.

Antibodies

Anti-Vav1 Abs were raised in rabbits against a specific peptide of Vav1, residues 528–541,17 and anti-PAR3 Abs were prepared by immunization of rabbits to keyhole limpet haemocyanin conjugated to the peptide H-TFRGAPPNS. Other antibodies used were: anti-phosphotyrosine (Ptyr), 4G10 (UBI, Lake Placid, NY); anti-CD3 (American Type Tissue Culture Collection); monoclonal anti-Vav1 used in Western blots (UBI); anti-paxillin mAbs, clone 349 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY); anti-thrombin receptor Abs (BIODESIGN International, Saco, MN); anti-Ly-GDI (UBI); anti-ZAP-70 Abs (kindly given to us by Dr N. Isakov, Ben-Gurion University, Beer-Sheva, Israel) and anti-SLP-76 Abs (a kind gift from Dr G. Koretzky, Philadelphia, PA).

Adhesion assay

Cells were grown in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FCS. After washing, cells were resuspended in a serum-free medium (0·5 × 106 cells/ml) and laid on 13-mm culture dishes, precoated with either fibronectin (FN; 100 mg/ml) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a control. Cells were allowed to adhere for 60 min and occasionally for as long as 2 hr, and then the non-adhered cells were washed off. Fixation was performed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS, pH 7·4, for at least 2 hr. The plates were washed in 1% boric acid solution and stained with 1% methylene blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) reagent in 1% boric acid for 30 min. After extensive washing with tap water, 500 µl of 1 m HCl was added to elute the methylene blue stain. Colour intensity was detected by spectrometry at 620 nm.

PAR agonist peptides

See Table 1.

Table 1.

Protease activated receptors (PARs) used in this study

| Ligand | Activating peptide | Detailed amino acid sequence of the activating peptide |

|---|---|---|

| PAR1 | SFLLRNPNDK | H-Ser-Phe-Leu-Leu-Arg-Asn-Pro-Asn-Asp-Lys-Nh2 |

| PAR2 | SLILGKVDGTS | H-Ser-Leu-Ile-Gly-Lys-Val-Asp-Gly-Thr-Ser-Nh2 |

| PAR3 | TFRGAPPNSF | H-Thr-Phe-Arg-Gly-Ala-Prp-Pro-Asn-Ser-Phe-Nh2 |

Results

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 by activation of PARs

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 has previously been shown to occur following stimulation of PAR1 in haematopoietic cells, such as platelets and megakaryocytes.18–20 However, thus far no detailed attempt has been made to elucidate the role of Vav1 in PAR signalling in T cells. In particular, no information was available about the potential involvement of Vav1 in PAR2- and PAR3-induced T cells. This prompted us to analyse whether activation of PAR1, PAR2 or PAR3, which are expressed in Jurkat T cells (refs 6, 7; and data not shown), would lead to increased tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 (Figs 1–3). Jurkat T cells were incubated with 100 µm of PAR1 (Fig. 1a), PAR2 (Fig. 2a) or PAR3 (Fig. 3a) agonist peptides for different time intervals (2, 5, 15 or 30 min). Lysates of these cells (lanes 3–6), as well as lysates of cells induced with OKT3 mAbs (lane 2) or non-induced (lane 1), were immunoprecipitated with anti-Vav1 Abs. These antibodies were raised against a unique Vav1 peptide and were shown by us to recognize specifically Vav1 and not the recently identified members of the Vav family, i.e. Vav2 and Vav3 (ref. 17 and data not shown). The immunocomplexes were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (Fig. 1a, 2a, 3a; upper panels). The level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 as compared to the amount of the protein loaded (Fig. 1a, 2a, 3a; lower panels) was quantified by densitometry (fold phosphorylation; Fig. 1b, 2b, 3b). As shown previously,12 stimulation of the TCR on Jurkat T cells by cross-linking with anti-CD3 (OKT3) mAbs led to increased tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 (Fig. 1a, 2a, 3a; lane 2 versus lane 1; upper panels). Our experiments clearly point to an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1, in response to all the PAR agonist peptides tested, in a time-dependent manner, although differences in the response between the various PARs exist (Fig. 1a, 2a, 3a; lanes 3–6 versus lane 1; upper panels and Fig. 1b, 2b, 3b). Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in response to PAR1 and PAR3 was observed to decline by 30 min after induction (Fig. 1a, 1b, 3a, 3b). In contrast, we observed a decline in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 15 min after stimulating Jurkat T cells with the PAR2-agonist peptide, which caused maximal stimulation after 5 min (Fig. 2a, 2b).

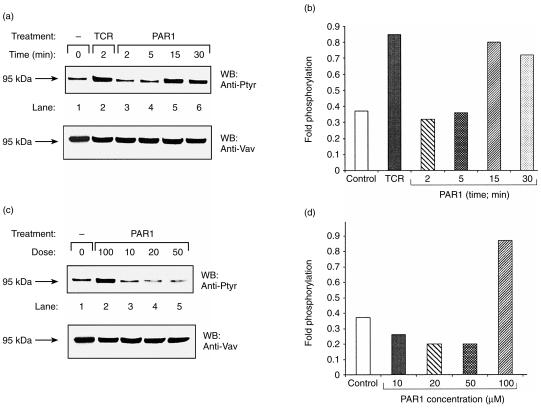

Figure 1.

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in a time-dependent (a) and (b), and dose–response (c) and (d), manner following stimulation of T cells with protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) peptide agonist. (a) Jurkat T cells were either non-activated (lane 1), OKT3 activated for 2 min (lane 2), or stimulated with 100 µm of peptide agonist for PAR1 for 2, 5, 15, or 30 min (lanes 3–6). The Jurkat T cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Vav1 antibodies (Abs). The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (upper panel) and rehybridized with anti-Vav1 Abs (lower panel). (b) The levels of phosphorylation and loaded proteins of the above experiment (a) were quantified. Fold phosphorylation relates to the intensity of phosphorylation versus the intensity of protein loaded in each lane. (c) As for (a) above, except that the Jurkat T cells were treated for 15 min with PAR1 agonist peptide at the following concentrations: 100 µm (lane 2), 10 µm (lane 3), 20 µm (lane 4) or 50 µm (lane 5). The arrow indicates the position of the product of Vav1 (95 kDa). (d) Fold phosphorylation of the experiment presented in (c) is shown.

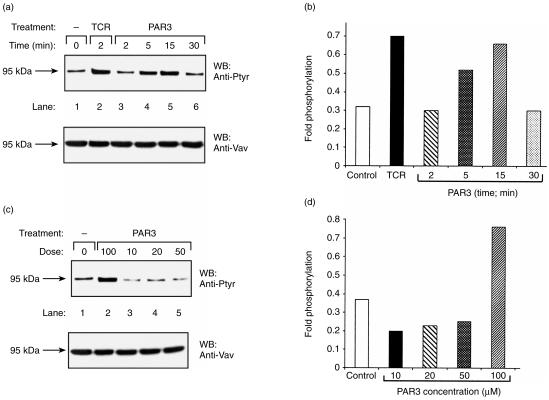

Figure 3.

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in a time-dependent (a) and (b), and dose–response (c) and (d), manner following stimulation of T cells with protease-activated receptor 3 (PAR3) peptide agonist. The experiment performed with PAR3 is similar to that described in the legend to Fig. 1.

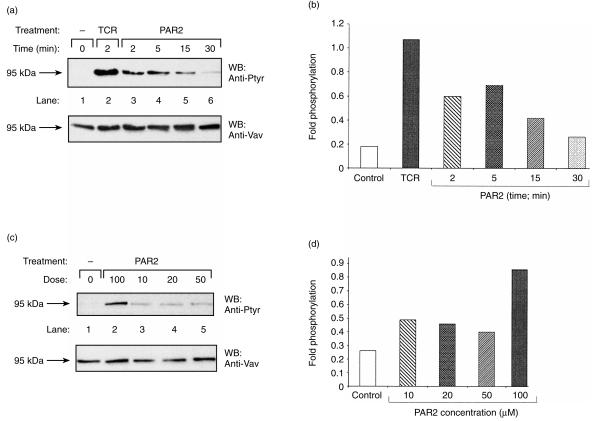

Figure 2.

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in a time-dependent (a) and (b), and dose–response (c) and (d), manner following stimulation of T cells with protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) peptide agonist. The experiment performed with PAR2 is similar to that described in the legend to Fig. 1, except that the Jurkat T cells were treated for 5 min with PAR2 agonist peptide at the various concentrations shown in (c).

Next we measured the effect on the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 following stimulation with various doses of agonist peptides for PAR1, PAR2 and PAR3 (Fig. 1c, 2c, 3c). For this purpose, Jurkat T cells were incubated with concentrations ranging from 10 to 100 µm of the inducing agonist peptides for 15 min for PAR1 and PAR3 (Fig. 1c, 3c, lanes 2–5) and for 5 min for PAR2 (Fig. 2c). Although comparable levels of Vav1 were present in the immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1c, 2c, 3c; lower panels), definite differences were observed in Vav1 phosphorylation. Thus, the highest level of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 was observed in response to the highest dose of the agonist PAR inducing peptides used, that is 100 µm (Fig. 1c, 2c, 3c; lane 2 versus lanes 3–5). These results were also verified by the quantification of the fold phosphorylation in the experiments (Fig. 1d, 2d, 3d). Taken together, our results show that activation of PAR1, PAR2 and PAR3 induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in Jurkat T-leukaemic cells.

Activation of JCaM1.6 cells with PAR peptide agonists fails to induce Vav1 phosphorylation

We then explored the possibility that activation of Vav1 by PARs may require several of the components of the TCR signalling machinery. The earliest events occurring after TCR stimulation involve the activation of multiple cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases, such as Lck and Fyn. This event leads to the phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-activation motifs (ITAM) of the TCR.21 After that, ZAP-70, a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase, associates through its two SH2 domains with two phosphorylated tyrosines in the ITAMs of the TCR.22 Subsequently, the phosphorylation of ZAP-70 by Src tyrosine kinases leads to the activation of its own kinase followed by the phosphorylation of downstream signalling proteins, such as Vav1.21 Lck has been shown to play a role in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in vitro, in vivo and also in overexpression systems.14,23 To test whether the increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in PAR-induced T cells is mediated by Lck, we used the mutant Jurkat T-cell line, JCaM1.6 (Fig. 4). JCaM1.6 cells lack a functional Lck tyrosine kinase and are therefore defective in mobilizing intracellular calcium, as well as several other TCR-mediated responses such as NF-AT activation.24 We first verified that JCaM1.6 cells express PAR1 and PAR3. For this purpose, lysates of Jurkat and JCaM1.6 cells were separated by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with Abs raised against PAR1, PAR3 and an unrelated protein, Ly-GDI (Fig. 4a). JCaM1.6 cells were found to express comparable amounts of PAR1 and PAR3 to Jurkat T cells (lane 2 versus lane 1, and lane 4 versus lane 3, respectively) while these proteins were undetected by unrelated Abs (lane 5). The higher intensity of PAR3 versus PAR1 observed in JCaM1.6 cells does not necessarily reflect a higher expression, but could rather stem from differences in the Abs used.

Figure 4.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 following stimulation of Jurkat T cells and JCaM1.6 mutant cells with protease-activated receptor (PAR) 1, 2 and 3 peptide agonists. (a) Lysates of Jurkat T cells (lanes 1, 3, 5) or JCaM1.6 cells (lanes 2, 4) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and immunoblotted with either anti-PAR1 antibodies (Abs) (lanes 1, 2), anti-PAR3 Abs (lanes 3, 4) or anti-LY-GDI Abs (lane 5). The arrows indicate the position of PAR1, PAR 3 and Ly-GDI. (b) Lysates of Jurkat T cells (lanes 1–5) or JCaM1.6 cells (lanes 6–10) were either non-activated (lanes 1, 6), OKT3 activated for 2 min (lanes 2, 7) or stimulated for 15 min with 100-µm concentrations of the peptide agonists PAR1 (lanes 3, 8), PAR2 (lanes 4, 9) or PAR3 (lanes 5, 10). Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Vav1 Abs, resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with either anti-Ptyr Abs (upper panel), or anti-Vav1 Abs (lower panel). The arrow indicates the position of the product of Vav1 (95 kDa). (c) Fold phosphorylation of (b) is depicted. Jurkat T cells (lanes 1–5) and JCAM1.6 (lanes 6–10) are depicted as black and grey boxes, respectively.

We next examined whether Vav1 is tyrosine phopshorylated in JCaM1.6 cells following PAR activation. Jurkat T cells (Fig. 4b; lanes 1–5) and JCaM1.6 cells (Fig. 4b; lanes 6–10) were either left untreated (Fig. 4b; lanes 1 and 6), or were activated with OKT3 mAbs (lanes 2 and 7) or with 100 µm agonist peptides for PAR1 (Fig. 4b; lanes 3 and 8), PAR2 (Fig. 4b, lanes 4 and 9) and PAR3 (Fig. 4b, lanes 5 and 10). Clearly, induction with OKT3 mAbs of JCaM1.6 cells (Fig. 4b, lane 7 versus lane 2), PAR1, PAR2 or PAR3 agonist peptides did not lead to tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1. In contrast, when Jurkat cells were treated similarly, there was a significant increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 (Fig. 4b, lanes 2–5 versus lane 1). These results were verified by quantification of the levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 as compared to the amount of the protein loaded (Fig. 4c). Thus, Lck seemed to be required for Vav1 phosphorylation in PAR-induced Jurkat T cells. However, these results do not necessary imply that under these stimulatory conditions Lck is directly responsible for Vav1 phosphorylation.

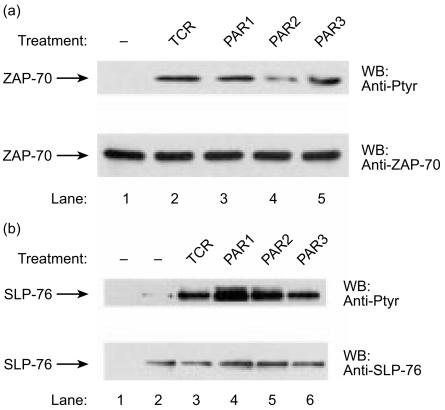

ZAP-70 and SLP-76 are involved in PAR-induced signalling cascades

ZAP-70 and SLP-76 have been shown to physically associate with Vav1,25,26 an association that is critical for the normal functioning of T cells, as exhibited by NF-AT stimulation and IL-2 production.27,28 No Vav1 phosphorylation has been detected in Jurkat T cells lacking an active ZAP-70 kinase,29 thus highlighting the critical significance of an active ZAP-70 for Vav1 function. While ZAP-70 functions as a kinase, SLP-76 (which is present in both T cells and myeloid cells) has no catalytic domains.30 SLP-76 is critical for TCR-mediated signalling, including the increase in Ca2+ release, stimulation of the Ras mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, activation of NF-AT and IL-2 production.31,32 Vav1 associates with ZAP-70 and SLP-76 via its SH2 domain.25,26 Elimination of the tyrosine residue in ZAP-70 and SLP-76 (that binds to Vav1) leads to abrogation of TCR-mediated signalling.29,31 To clarify whether ZAP-70 and SLP-76 participate in PAR-induced Vav1 activation, we first used the highly sensitive glutathione-S-transferase (GST) in vitro binding assay to investigate whether, following PAR stimulation, these proteins physically associate with the Vav1 SH2 region (Fig. 5). GST (Fig. 5, lanes 1–5) and the SH2 region of Vav1, expressed as a GST bacterial fusion protein (GSTVav1SH2) (Fig. 5, lanes 6–10), were immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads. These proteins were then bound to lysates of Jurkat T cells that were either untreated (Fig. 5; lanes 1 and 6), induced with OKT3 mAbs (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 7), or treated with peptide agonists for PAR1 (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 8), PAR2 (Fig. 5, lanes 4 and 9) or PAR3 (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 10). The bound proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (Fig. 5). Associated with GSTVav1SH2 from lysates of TCR- or PAR-induced cells we found two proteins, of which one of 70000 molecular weight (MW) potentially corresponded to ZAP-70 and the other of 76000 MW potentially corresponded to SLP-76.

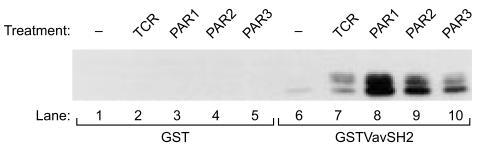

Figure 5.

Association of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins from protease-activated receptor (PAR) 1 and PAR3 peptide agonist-stimulated T cells to the Src homology 2 (SH2) domain of Vav1. Glutathione-S-transferase (GST; lanes 1–5) and the SH2 domain of Vav1, expressed as a GST protein (GSTVav1SH2; lanes 6–10), were immobilized on glutathione sepharose beads. The bacterial fusion proteins were then incubated with lysates of Jurkat cells that were either non-activated (lanes 1, 6), OKT3 activated for 2 min (lanes 2, 7) or stimulated for 15 min with 100-µm concentrations of the peptide agonists PAR1 (lanes 3, 8), PAR2 (lanes 4, 9), or PAR3 (lanes 5, 10). The proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr.

Based on these results, we investigated whether ZAP-70 and SLP-76, two proteins known to play a critical role in the induction of Vav1 in T cells,28,29,31,32 might also participate in PAR-induced signalling (Fig. 6). We detected an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 (Fig. 6a, lanes 3–5 versus lane 1) and SLP-76 (Fig. 6b, lanes 4–6 versus lane 2) following treatment of the cells with the agonist peptides for PAR1, PAR2 and PAR3 receptors, respectively. Our results indicate that both SLP-76 and ZAP-70 are phosphorylated in T cells induced by PAR peptide agonists.

Figure 6.

Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of ZAP-70 (a) and SLP-76 (b) following stimulation of T cells with protease-activated receptor (PAR) 1, PAR2 and PAR3 peptide agonists. Jurkat T cells were either non-activated (a, lane 1; b, lanes 1, 2), OKT3 activated for 2 min (TCR; lane 2), or stimulated for 15 min with 100-µm concentrations of the peptide agonists PAR1 (lane 3), PAR2 (lane 4) or PAR3 (lane 5). Cells were lysed and then immunoprecipitated with anti-ZAP-70 (a), anti-SLP-76 (b, lanes 2–6) antibodies (Abs) or pre-immune sera (b, lane 1). The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (A and B; upper panel), and rehybridized with either anti-ZAP-70 Abs (A; lower panel) or anti-SLP-76 (B; lower panel). The arrows indicate the position of ZAP-70 and SLP-76, respectively.

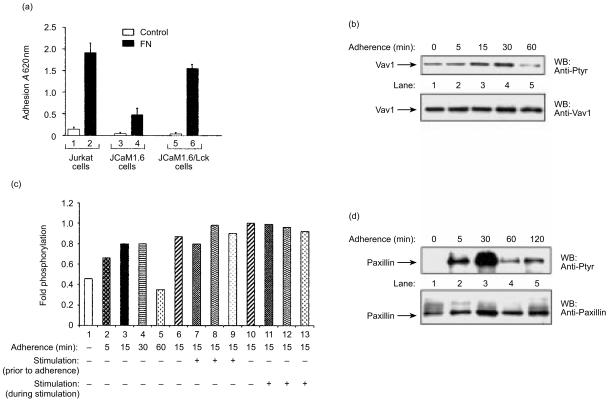

FN-induced Vav1 phosphorylation in Jurkat T-lymphoid cells

Previous studies have shown that Jurkat T cells, normally present in suspension, adhere strongly to FN.33–35 The β1-integrins, α4β1 and α5β1, are considered to be the main FN receptors and are therefore primarily involved in Jurkat T-cell adhesion to FN. These integrins can also function as costimulatory molecules participating in signalling of TCR activation. We reasoned that analysing the adhesion properties of JCaM1.6 mutant cells might assist us in evaluating the integrin-associated signalling pathways. Therefore, we compared the adhesion (at 37° for 45 min) of Jurkat cells, Jurkat cells reconstituted with Lck (JCaM/Lck), or JCaM1.6 cells (1 × 106 cells/ml), in a serum-free medium to FN-coated plates with their adhesion to control plates coated with BSA (Fig. 7a). Compared to the level of adhesion of Jurkat cells (lane 2), the adherence of JCaM1.6 cells to FN was low (20%; Fig. 7a, lane 4). The level of adhesion of JCaM/Lck resembled that of Jurkat T cells, although was somewhat lower (80%; Fig. 7a, lane 6). This difference probably stems from the fact that JCaM/Lck are not fully reconstituted and express a somewhat lower level of Lck than Jurkat T cells (A. Weiss, personal communication). The low adhesion of the JCaM1.6 cells was probably a result of their lack of p56Lck, suggesting that p56Lck may be involved in integrin engagement.

Figure 7.

Induction of Vav1 phosphorylation following adherence to fibronectin (FN)-coated substrata is independent of protease-activated receptor (PAR) activation. (a) Adhesion to FN-coated substrata of Jurkat T cells (lanes 1, 2), JCaM1.6 (lanes 3, 4) and JCaM/Lck (lanes 5, 6). Jurkat T cells, JCaM1.6 and JCaM/Lck cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were allowed to adhere (at 37° for 45 min) in serum-free medium onto FN-coated plates (black bar). The level of adhesion to control plates coated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) was determined (open bar). The level of adherence was assessed as detailed in the Materials and methods. The experiment was performed three times in duplicate. The error bars represent the standard deviation. A, absorbance. (b) Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in Jurkat T cells following adherence to FN-coated plates. Cells either in suspension (lane 1) or adherent for various periods of time (5, 15, 30 or 60 min; lanes 2–5) were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-Vav1 antibodies (Abs). The immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE), immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (upper panel) and rehybridized with anti-Vav1 Abs (lower panel). (c) Activation with PARs does not affect Vav1 phosphorylation following adherence to FN. Jurkat T cells were either in suspension (lane 1) or adherent for various periods of time (5, 15, 30 or 60 min; lanes 2–5). In addition, Jurkat T cells were either not induced (lane 6) or induced for 15 min with PAR1 (lane 7), PAR2 (lane 8) or PAR3 (lane 9) and then adhered to FN-coated substrata for 15 min. Also, Jurkat T cells were adhered to FN-coated substrata for 15 min and were then either not induced (lane 10) or induced with PAR1 (lane 11), PAR2 (lane 12) or PAR3 (lane 13) during adherence. Cells were then lysed, immunoprecipitated with anti-Vav1 Abs, separated by SDS–PAGE and the fold phosphorylation was then determined. The figure is representative of three such experiments. (d) Kinetics of paxillin phosphorylation following adhesion to FN. Cells were lysed seither prior to (lane 1) or after adherence to FN for various time periods (5, 30, 60, or 120 min; lanes 2–5), and immunoprecipitated with anti-paxillin Abs. The immunoprecipitants were resolved as described above, immunoblotted with anti-Ptyr Abs (upper panel) and rehybridized with anti-paxillin Abs (lower panel).

We next wished to evaluate whether PAR activation could be involved in the Vav1 tyrosine phosphorylation during integrin clustering. Jurkat T cells were allowed to adhere to plates coated with FN for the indicated periods of time (Fig. 7b, lanes 2–5). We compared the level of phosphorylation of Vav1 (Fig. 7b, lanes 2–5) in the FN-bound cells to that in an equal number of cells in suspension (Fig. 7b, lane 1). By 5 min, nearly all of the cells in the FN-coated plates had adhered to the substratum and by 30 min cell spreading was observed (data not shown). In these cells, we detected an elevation in the phosphorylation of Vav1 as soon as 15 min after cell adhesion (Fig. 7b, lane 3), which reached a maximal increase after 30 min (Fig. 7b, lane 4) and declined thereafter (Fig. 7b, lane 5). When the cells were in suspension, Vav1 phosphorylation was low (Fig. 7b, lane 1). We then evaluated the possible contribution of PARs to Vav1 phosphorylation following adherence to FN. Jurkat T cells were either treated for 15 min with PAR agonist peptides prior to their adherence for 15 min to FN (Fig. 7c, lanes 7–9) or stimulated with PAR agonist peptides for 15 min during adherence to FN (Fig. 7c, lanes 10–12). It is noteworthy that no additional phosphorylation of Vav1 was illustrated following treatment of Jurkat T cells either prior to their adhesion to FN (Fig. 7c, lanes 7–9) or during adherence (Fig. 7c, lanes 11–13). In addition, no increased adherence was noted under the above mentioned conditions (data not shown). These results suggest that PAR activation does not increase the activation of Vav1 following integrin engagement.

The clustering of FN receptors leads to the formation of focal adhesion complexes (FACs), which are characterized, amongst others, by signalling proteins such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and paxillin.36–38 While FAK is a tyrosine kinase that serves as a scaffold protein for multiple cytoskeletal and signalling proteins, paxillin serves as a cytoskeletal protein localized abundantly at FAC sites. In the cells adhered to FN-coated plates, we observed a profound time-dependent increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin (Fig. 7d), with a significant increase 5 min after adherence, reaching a maximum level at 30 min (Fig. 7d, lane 3). While no phosphorylation of paxillin was observed in cells present in suspension (Fig. 7d, lane 1), the tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin was transient and declined by 60 min and thereafter (Fig. 7d, lanes 4 and 5). We conclude that in FN-adherent Jurkat T cells, maximal paxillin phosphorylation (Fig. 7d, lane 3) and Vav1 phosphorylation (Fig. 7b, lane 4) is reached by 30 min.

Discussion

Our ability to dissect signalling cascades initiated by stimulation of PARs in T cells is dependent on identifying the various proteins that participate in these processes. Previously, it has been reported that in various types of cells, the activation of G-coupled receptors, or specifically PAR1 and integrins, lead to the induction of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1.17–19,39–42 Notwithstanding, here we report for the first time that, in T cells, in addition to stimulation of PAR1, stimulation of the newly identified receptors PAR2 and PAR3 also led to the activation of Vav1 (Figs 1–3). We did find, however, that stimulation of T cells with the various PAR proteins led to varied levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1. This was especially apparent when we compared the phosphorylation of Vav1 in response to stimulation by PAR2 with the response to stimulation by PAR1 or PAR3 (Figs 1–3). These differences could stem from the fact that, in contrast to PAR1 and PAR3, PAR2 is a non-thrombin receptor6,7 and therefore its mode of action might differ. It is noteworthy that the murine homologue of PAR3 also exhibits an interesting mode of mechanism of PAR activation.43 While PAR3 by itself did not confer signalling, co-expression with PAR4 enhanced signalling at a low concentration of thrombin. Thus, PAR3 mainly functions as a co-activator of PAR4, as best shown in platelet signalling. However, the mode of action of PAR3 in humans has not yet been fully explored. It is plausible that in T cells, PAR3 also operates in conjunction with PAR4, although this possibility remains to be elucidated.43 Vav1 is known to participate in TCR-mediated events.10–13 Our results illustrate distinctly that Vav1 also plays a role in PAR signalling cascades in T cells.

Several of the signal transducer proteins that participate in TCR and PAR signalling have also been shown to participate in events initiated by the beta-1 integrins. Src family tyrosine kinases (Lck and Fyn) and Syk family kinases (Syk and ZAP-70) were shown to be involved in tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in haematopoietic cells.11,44 The data we present here suggest that Lck is an important element in PAR- and integrin-induced signalling cascades (Fig. 4, Fig. 7). The low adherence to FN substratum of JCaM1.6 cells (Fig. 7a) could probably be attributed to the presence of Fyn in these cells. Indeed, tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 in Lck-deficient but Fyn-positive JCaM1.6 cells following CD28 stimulation was demonstrated.45 However, it is important to note that although Fyn is able to mediate TCR signal transduction pathways, it utilizes a mechanism distinct from that used by Lck.45 This alternative pathway leads to a restricted induction of downstream signalling events as compared to those induced in Jurkat T cells. Moreover, processes such as stimulation of NF-AT and IL-2 production, in which Vav1 was shown to participate, are defective in JCaM1.6 cells.45 Thus, p56Lck is a major component involved in PAR induction and integrin engagement. Previously, Lck has been shown to exert negative control on thrombin-induced p38 MAPK activation and [Ca2+] release in Jurkat cells.46,47 Moreover, it is noteworthy that Lck was recently suggested to negatively regulate the activity of Vav1 in T cells following TCR stimulation.48,49 It is highly probable therefore that Lck might also be involved in the negative regulation of Vav1 activity in PAR-mediated T-cell signalling and integrin engagement.

Our results show that in addition to Vav1 and Lck, PAR signalling in T cells involves SLP-76 and ZAP-70, two other key proteins in TCR activation (Fig. 6). In contrast to our findings here, in studies in Jurkat T cells by Gross and colleagues,50 SLP-76 was shown to be only mildly tyrosine phosphorylated in response to stimulation by PAR1. Note, however, that the reason for this discrepancy might be explained by the fact that in our studies the cells were stimulated for 15 min while in the other studies the cells were stimulated for only 1 min. Thus far, no reports have implicated ZAP-70 or the other member of this tyrosine kinase family of proteins, Syk, in PAR-induced phosphorylation of Vav1. While Syk is expressed in B lymphocytes, immature T cells, natural killer (NK) cells and basophils, ZAP-70 is found predominantly in T cells.51,52 Miranti and colleagues41 determined that Syk is involved in integrin-mediated Vav1 phosphorylation. Thus, when Syk was not present there is no apparent phosphorylation of Vav1. Even though in that study the cells system and mode of cell stimulation were different from those of our present study (Fig. 5, Fig. 6), the results41 support our conclusion that ZAP-70 (a member of the Syk tyrosine kinase family of proteins) and SLP-76 may play a cardinal role in PAR-induced T-cell signalling events. The importance of the Syk tyrosine kinase in integrin-mediated processes was recently reported also for the other members of the Vav family of signal transducer proteins, i.e. Vav2 and Vav3.53,54

We show here that while Vav1 is phosphorylated following β1 integrin ligation (Fig. 7b), the activation of adherent T cells with PARs did not lead to a further increase in Vav1 phosphorylation (Fig. 7c). We have previously shown that activation of PAR1 in tumour melanoma cells leads to αvβ5 integrin activation followed by induced FAC formation, cytoskeletal reorganization and paxillin phosphorylation.55 The fact that integrin activation bypasses PAR1-induced Vav1 phosphorylation in T cells points to the possibility that PAR1 probably activates signal transduction events similar to those induced by integrins. Indeed, several of the proteins that associate with Vav1, such as ZAP-70 and SLP-76 in T cells and Tec in platelets, were also shown to be induced by PAR1. Similar proteins are also induced by integrins. Once integrin ligation/activation takes place, the activated kinases (Src and Syk family proteins) are fully functional, thus leading to maximal phosphorylation of Vav1.

The question then arises of whether additional signal transducer proteins that participate in events initiated in CD3/TCR-activated T cells, also concur in signalling pathways following activation of β1-integrin. A recent study distinctly established that the tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 is critical for the regulation of β1-integrin activity by the CD3/TCR in Jurkat T cells,56 yet the two adapter proteins, LAT and SLP-76, do not participate in such events. Whether these two adapter proteins participate in integrin-induced adhesion, regardless of the TCR induction, is unclear. Furthermore, the results presented here and by others40–42 verify that Vav1 participates in TCR-, PARs- and integrin-induced processes in T cells. Apparently, several of the key signalling proteins participate in diverse signalling events initiated in the cell, whereas others play a more restricted function.

Stimulation of T cells with thrombin receptor agonist peptides results in the initiation of signalling events, including increased intracellular Ca2+ and the activation of protein kinase C, leading to the stimulation of NF-κB56 and also the phosphorylation of target proteins on tyrosine residues.8 Activated PAR1 leads finally to mitogensis in T cells, the production of IL-2 and the activation of antigen CD69, which are also induced by TCRs.8 Identifying the signalling molecules that participate in PARs-induced events in T cells is important for our understanding of such pathways. We have presented data showing that Vav1, as well as Lck, ZAP-70 and SLP-76, are critically involved in PAR-mediated signalling of T cells. We have contributed thus, in clarifying part of the signalling puzzle that is initiated in T cells by PARs.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr N. Isakov and Dr G. Koretzky for the gift of the Abs and to Dr A. Weiss for the gift of the JCaM/Lck cells. This work was supported by grants from the Israel Science Foundation founded by the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities and by grants from the Israel Cancer Association given to S.K. and R.B.S.

References

- 1.Vu TKH, Hung DT, Wheaton VI, Coughlin SR. Molecular cloning of a functional thrombin receptor reveals a novel proteolytic mechanism of receptor activation. Cell. 1991;64:1057–68. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90261-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coughlin SR. How the protease thrombin talks to cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11023–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hung DT, Vu TKH, Wheaton VI, Charo IF, Nelken NA, Esmon CT, Coughlin SR. Cloned thrombin receptor is necessary for thrombin-induced platelet activation. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:444–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI115604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishihara H, Connolly AJ, Zeng D, Kahn ML, Zheng YW, Timmons C, Tram T, Coughlin SR. Protease-activated receptor 3 is a second thrombin receptor in humans. Nature. 1997;386:502–6. doi: 10.1038/386502a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu WF, Andersen H, Whitmore TE, et al. Cloning and characterization of human protease-activated receptor 4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6642–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nystedt S, Ramakrishnan V, Sundelin J. The proteinase-activated receptor 2 is induced by inflammatory mediators in human endothelial cells. Comparison with the thrombin receptor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14910–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergnolle N, Macnaughton WK, Al-Ani B, Saifeddine M, Wallace JL, Hollenberg MD. Proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2)-activating peptides: identification of a receptor distinct from PAR2 that regulates intestinal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7766–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mari B, Imbert V, Belhacene N, et al. Thrombin and thrombin receptor agonist peptide induce early events of T cell activation and synergize with TCR cross-linking for CD69 expression and interleukin 2 production. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8517–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katzav S, Martin-Zanca D, Barbacid M. Vav, a novel human oncogene derived from a locus ubiquitously expressed in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1989;8:2283–90. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katzav S. Vav: Captain Hook for signal transduction? Crit Rev Oncog. 1995;6:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bustelo XR. Regulatory and signaling properties of the Vav family. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1461–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1461-1477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margolis B, Hu P, Katzav S, Li W, Oliver JM, Ullrich A, Weiss A, Schlessinger J. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav proto-oncogene product containing SH2 domain and transcription factor motifs. Nature. 1992;356:71–4. doi: 10.1038/356071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustelo XR, Ledbetter JA, Barbacid M. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Vav proto-oncogene product in activated B cells. Nature. 1992;356:68–71. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crespo P, Schuebel KE, Ostrom AA, Gutkind JS, Bustelo XR. Phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of Rac-1 GDP/GTP exchange by the Vav proto-oncogene product. Nature. 1997;385:169–72. doi: 10.1038/385169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holsinger LJ, Graef IA, Swat W, et al. Defects in actin-cap formation in Vav-deficient mice implicate an actin requirement for lymphocyte signal transduction. Curr Biol. 1998;8:563–72. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer KD, Kong YY, Nishina H, et al. Vav is a regulator of cytoskeletal reorganization mediated by the T-cell receptor. Curr Biol. 1998;8:554–62. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cichowski K, Brugge JS, Brass LF. Thrombin receptor activation and integrin engagement stimulate tyrosine phosphorylation the proto-oncogene product, p95Vav1, in platelets. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7544–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cichowski K, Orsini MJ, Brass LF. PAR1 activation initiates integrin engagement and outside-in signalling in megakaryoblastic CHRF-288 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1450:265–76. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyakawa Y, Oda A, Druker BJ, Ozaki K, Handa M, Ohashi H, Ikeda Y. Thrombopoietin and thrombin induce tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav in human blood platelets. Blood. 1997;89:2789–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katzav S, Cleveland JL, Heslop HE, Pulido D. Loss of the amino-terminal helix-loop-helix domain of the vav proto-oncogene activates its transforming potential. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1912–20. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.4.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Oers NS, Killeen N, Weiss A. Lck regulates the tyrosine phosphorylation of the T cell receptor subunits and ZAP-70 in murine thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1053–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isakov N, Wange RL, Burgess WH, Watts JD, Aebersold R, Samelson LE. ZAP-70 binding specificity to T cell receptor tyrosine-based activation motifs: the tandem SH2 domains of ZAP-70 bind distinct tyrosine-based activation motifs with varying affinity. J Exp Med. 1995;181:375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han J, Das B, Wei W, et al. Lck regulates Vav1 activation of members of the Rho family of GTPases. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1346–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Straus DB, Weiss A. Genetic evidence for the involvement of the lck tyrosine kinase in signal transduction through the T cell antigen receptor. Cell. 1992;70:585–93. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90428-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzav S, Sutherland M, Packham G, Yi T, Weiss A. The protein tyrosine kinase ZAP-70 can associate with the SH2 domain of proto-Vav. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32579–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tuosto L, Michel F, Acuto O. p95Vav associates with tyrosine-phosphorylated SLP-76 in antigen-stimulated T cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1161–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J, Katzav S, Weiss A. A functional T-cell receptor signaling pathway is required for p95Vav1 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4337–46. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang N, Koretzky GA. SLP-76 and Vav function in separate, but overlapping pathways to augment interleukin-2 promoter activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16206–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu J, Zhao Q, Kurosaki T, Weiss A. The Vav binding site (Y315) in ZAP-70 is critical for antigen receptor-mediated signal transduction. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1877–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackman JK, Motto DG, Sun Q, Tanemoto M, Turck CW, Peltz GA, Koretzky GA, Findell PR. Molecular cloning of SLP-76, a 76-kDa tyrosine phosphoprotein associated with Grb2 in T cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7029–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu J, Motto DG, Koretzky GA, Weiss A. Vav and SLP-76 interact and functionally cooperate in IL-2 gene activation. Immunity. 1996;4:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yablonski D, Kuhne MR, Kadlecek T, Weiss A. Uncoupling of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases from PLC-gamma1 in an SLP-76-deficient T cell. Science. 1998;281:413–6. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bearz A, Tell G, Formisano S, Merluzzi S, Colombatti A, Pucillo C. Adhesion to fibronectin promotes the activation of the p125 (FAK)/Zap-70 complex in human cells. Immunology. 1999;98:564–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwata S, Ohashi Y, Kamiguchi K, Morimoto C. Beta 1-integrin-mediated cell signaling in T lymphocyte. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;23:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(99)00096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner CE, Glenney JR, Burridge KJ. Paxillin: a new vinculin-binding protein present in focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1059–68. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burridge K, Turner CE, Romer LH. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlaepfer DD, Hauck CR, Sieg DJ. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;71:435–78. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bockholt SM, Burridg KJ. Cell spreading on extracellular matrix proteins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of tensin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14565–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zheng L, Sjolander A, Eckerdal J, Andersson T. Antibody-induced engagement of beta 2 integrins on adherent human neutrophils triggers activation of p21ras through tyrosine phosphorylation of the protooncogene product Vav1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gotoh A, Takahira H, Geahlen RL, Broxmeyer HE. Cross-linking of integrins induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the proto-oncogene product Vav1 and the protein tyrosine kinase Syk in human factor-dependent myeloid cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:721–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miranti CK, Leng L, Maschberger P, Brugge JS, Shattil SJ. Identification of a novel integrin signaling pathway involving the kinase Syk and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1289–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00559-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yron I, Deckert M, Reff ME, Munshi A, Schwartz MA, Altman A. Integrin-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation and rowth regulation by Vav. Cell Adhes Commun. 1999;7:1–11. doi: 10.3109/15419069909034388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakanishi-Matsui M, Zheng YW, Sulciner DJ, Weiss EJ, Ludeman MJ, Coughlin SR. PAR3 is a cofactor for PAR4 activation by thrombin. Nature. 2000;404:609–13. doi: 10.1038/35007085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michel F, Grimaud L, Tuosto L, Acuto O. Fyn and ZAP-70 are required for Vav1 phosphorylation in T cells stimulated by antigen-presenting cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31932–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denny MF, Patai B, Straus DB. Differential T-cell antigen receptor signaling mediated by the Src family kinases Lck and Fyn. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1426–35. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.4.1426-1435.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joyce DE, Chen Y, Erger RA, Koretzky GA, Lentz SR. Functional interactions between the thrombin receptor and the T-cell antigen receptor in human T-cell lines. Blood. 1997;90:1893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maulon L, Guerin S, Ricci JE, Breittmayer DF, Auberger P. T-cell receptor signaling pathway exerts a negative control on thrombin-mediated increase in [Ca2+]I and p38 MAPK activation in Jurkat T cells: implication of the tyrosine kinase p56Lck. Blood. 1998;91:4232–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhne MR, Ku G, Weiss A. A guanine nucleotide exchange factor-independent function of Vav in transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2185–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lopez-Lago M, Lee H, Cruz C, Movilla N, Bustelo XR. Tyrosine phosphorylation mediates both activation and downmodulation of the biological activity of Vav. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:1678–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1678-1691.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gross BS, Lee JR, Clements JL, Turner M, Tybulewicz VL, Findell PR, Koretzky GA, Watson SP. Tyrosine phosphorylation of SLP-76 is downstream of Syk following stimulation of the collagen receptor in platelets. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5963–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chu DH, Morita CT, Weiss A. The Syk family of protein tyrosine kinases in T-cell activation and development. Immunol Rev. 1998;165:167–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Briddon SJ, Watson SP. Evidence for the involvement of p59fyn and p53/56lyn in collagen receptor signalling in human platelets. Biochem J. 1999;338:203–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moores SL, Selfors LM, Fredericks J, Breit T, Fujikawa K, Alt FW, Brugge JS, Swat W. Vav family proteins couple to diverse cell surface receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6364–73. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6364-6373.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu BP, Burridge K. Vav2 activates Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA downstream from growth factor receptor but not beta1 integrins. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7160–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7160-7169.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Even-Ram Cohen S, Maoz M, Pokroy E, Reich R, Katz BZ, Gutwein P, Altevogt P, Bar-Shavit R. Tumor cell invasion is promoted by activation of Protease Activated Receptor-1 in cooperation with the αvβ5 integrin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10952–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Epler JA, Liu R, Chung H, Ottoson NC, Shimizu Y. Regulation of beta (1) integrin-mediated adhesion by T cell receptor signaling involves ZAP-70 but differs from signaling events that regulate transcriptional activity. J Immunol. 2000;165:4941–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.4941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]