Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanisms by which interleukin-10 (IL-10) induces tumour growth in a mouse-melanoma model. A B16-melanoma cell line (B16-0) was transfected with IL-10 cDNA and three clones that secreted high (B16-10), medium and low amounts of IL-10 were selected. Cell proliferation and IL-10 production were compared in vitro, and tumour growth, percentages of necrotic areas, tumour cells positive for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) and major histocompatibility complex type I (MHC-I) and II (MHC-II), as well as infiltration of macrophages, CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and blood vessels were compared in vivo among IL-10-transfected and non-transfected tumours. Proliferation and tumour growth were greater for IL-10-transfected than for non-transfected cells (P < 0·001), and correlated with IL-10 concentration (r ≥ 0·79, P < 0·006). Percentages of tumour cells positive for PCNA and IL-10R were 4·4- and 16·7-fold higher, respectively, in B16-10 than in B16-0 tumours (P < 0·001). Macrophage distribution changed from a diffuse pattern in non-transfected (6·4 ± 1·7%) to a peripheral pattern in IL-10-transfected (3·8 ± 1·7%) tumours. The percentage of CD4+ lymphocytes was 7·6 times higher in B16-10 than in B16-0 tumours (P = 0·002). The expression of MHC-I molecules was present in all B16-0 tumour cells and completely negative in B16–10 tumour cells. In B16-0 tumours, 89 ± 4% of the whole tumour area was necrotic, whereas tumours produced by B16-10 cells showed only 4·3 ± 6% of necrotic areas. IL-10-transfected tumours had 17-fold more blood vessels than non-transfected tumours (61·8 ± 8% versus 3·5 ± 1·7% blood vessels/tumour; P < 0·001). All the effects induced by IL-10 were prevented in mice treated with a neutralizing anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibody. These data indicate that IL-10 could induce tumour growth in this B16-melanoma model by stimulation of tumour-cell proliferation, angiogenesis and immunosuppression.

Introduction

A contribution by immunosuppressive cytokines to tumour progression in many types of cancer has been previously suggested.1,2 Interleukin-10 (IL-10) is a T helper type 2 (Th2)-type pleiotropic cytokine that is produced at the tumour site and is increased in sera of patients suffering from different cancer types.3 IL-10 has been shown to hinder a number of immune functions, i.e. T-lymphocyte proliferation, Th1-type cytokine production, antigen presentation, and lymphokine-activated killer cell cytotoxicity.4 One of the main actions of this cytokine is its ability to inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-1 and IL-12, which are synthesized by macrophages in response to bacterial components, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS)5. This activity results in decreased interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production by macrophages and Th1 lymphocytes and inhibition of cell-mediated immune responses, while concomitantly enhancing humoral immunity.6–9 Furthermore, IL-10 strongly reduces antigen-specific T-cell proliferation by inhibiting the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes through down-regulation of their major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) expression.10 On the other hand, IL-10 is endowed with multiple positive regulatory activities: it is a growth factor for mature and immature T cells,11 it enhances the growth and differentiation of CD28+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs),12 and it induces MHC-II expression on resting B cells sustaining their viability in vitro.13

Since IL-10 has potent immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties and is produced by some cancers, it has been hypothesized that its production by tumour cells may contribute to the escape from immune surveillance.3,14–16 However, the results obtained on in vivo models are controversial. The Lewis lung carcinoma cells have more aggressive growth potential in IL-10-transgenic mice compared with control littermates.15 On the other hand, IL-10-transfected adenocarcinoma cells derived from BALB/c mice did not show an enhanced ability to grow. Instead, these cells undergo complete rejection due to the combined action of CD8+ lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and neutrophils.17 In a nude mouse melanoma model, IL-10 gene transfer of A375P-melanoma cells resulted in a loss of metastasis and significant inhibition of tumour growth.16 In addition, the growth of other murine and human melanoma cells was also inhibited when they were admixed with IL-10-transfected cells before injection into nude mice.16

It has been shown that IL-10 can be an autocrine growth factor in culture cells.18,19 The participation of this mechanism in cell proliferation has not been previously studied in tumour models and it is not known if contradictory results related to the effect of IL-10 on tumour growth could be associated with a different behaviour of the tumour cells in this autocrine pathway. To construct a global view of the role of IL-10 in tumour growth, it is important to dissect its direct function as an autocrine proliferation factor from its contribution to induce immune surveillance escape.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of IL-10 on tumour growth in a mouse melanoma model and the induction mechanism of cell proliferation, either through autocrine stimulation of tumour cells or just through depression of the immune system.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The melanoma-B16 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville MD). This cell line was derived from a spontaneous tumour of C57BL/6 origin. B16 cells are tumorigenic subcutaneously and do not express IL-10. B16 (B16-0) and IL-10-transfected B16 cells were maintained in culture as adherent monolayers in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's minimal essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), l-glutamine and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco BRL; Rockville MD). The J774 cell line was derived from mouse monocyte–macrophage. These cells were maintained in culture in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, l-glutamine and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco BRL).

Mice

Pathogen-free male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Biomedical Research Institute at the National University of Mexico and were used at 12–15 weeks of age. All animal work was performed to conform with the Local Ethical Committee for Experimentation on Animals in Mexico.

IL-10 cloning and transfection

Total RNA was isolated from mouse spleen lymphocytes treated for 8 hr with 10 µg/ml concanavalin A (Sigma Chemical Co.; St Louis MO). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the reverse transcriptase kit (Perkin-Elmer; Branchburg, NJ). The cDNA was incubated at 95° for 5 min to inactivate the reverse transcriptase and served as a template DNA for 30 rounds of amplification using the Perkin-Elmer thermocycler. The cDNA was amplified using two IL-10-specific primers. Primer sequences incorporating Xba I or Not I sites are as follows: 5′-AGCGCGGCCGCATGCCTGGCTCAGCACTGCTA-3′ and 5′-AGCTCATAGATCATTTTGATCATCATGTATG-3′. Amplification was performed for 30 seconds at 95°, 30 seconds at 55°, 30 seconds at 72°. Finally an additional extension step was performed for 10 min at 72°. The product was cloned into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen; Groningen, the Netherlands). B16 cells were transfected using the calcium phosphate method and stable transfections were carried out as described previously.20 Cells resistant to 600 µg/ml of the antibiotic G418 (Boehringer-Mannheim; Mannheim, Germany) were selected over a 3-month period. Single cell clones were generated by limited dilution in 96-well plates and three clones that secreted high (B16-10), medium (B16-13) and low (B16-5) amounts of IL-10 were selected. The cell clones were frozen in liquid nitrogen for future studies.

Nitrite determinations

Macrophages were cultured as adherent monolayers in 24-well plates at an initial density of 70000 cells/well. The cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS for 6 hr. The medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Macrophages were incubated with supernatants from IL-10-transfected or non-transfected cells for 3 hr, the supernatants were removed and the cells were washed twice. Then they were stimulated with 10 ng LPS (Sigma Chemical Co.) and 100 ng IFN-γ (Schering-Plough, Mexico City, Mexico) in 500 µl RPMI-1640 for 48 hr. Finally, 100 µl of each supernatant was collected and incubated with an equal volume of Griess reagent (1% sulphanilamide/0·1% naphthylethylene diamine dihydrochloride/2·5% H3PO4) at room temperature for 10 min. The reaction product was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 550 nm. NO2 concentration was determined using sodium nitrite as a standard.

Cell proliferation assay

The cell proliferation assay was carried out with a colorimetric kit [5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine (BrdU) incorporation; Boehringer-Mannheim] according to manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1440 tumour cells/well were grown in triplicate in 96-well plates (NUNC, Naperville, IL) in 200 µl DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 24 hr. Cells were then supplemented with 3 µg/ml IL-10-neutralizing antibody or with medium alone and incubated for 48 hr. The cells were then labelled by the addition of 20 µl BrdU for 5 hr. After removing the labelling medium, the cells were fixed and the DNA was denatured by adding FixDenat. Then the anti-BrdU antibody conjugated with peroxidase was added. The peroxidase activity was detected colorimetrically by measuring the oxidized chromogen (tetramethyl-benzidine) at 370 or 492 nm.

Tumorigenicity

Cells in the exponential growth phase were harvested at 80% confluence, briefly exposed to 0·1% trypsin solution and pipetted to obtain a homogeneous cell suspension. Cell suspension was centrifuged at 418·8 g for 5 min, washed once with PBS and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. Cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. Only single-cell suspensions with 95% viability were used for inoculation. For tumorigenesis experiments, four groups of 14 C57BL/6 mice were injected subcutaneously with 3 × 105 cells of B16-0, B16-5, B16-10, or B16-13 cell lines suspended in 150 µl of PBS into the left thigh. Tumour growth was monitored for 18 days in six animals of each group. Two bisecting diameters of each tumour were measured with callipers. The volume was calculated using the formula (0·4 ab2), with ‘a’ as the larger diameter and ‘b’ as the smaller diameter.15 Two mice from each group were killed on days 13, 14, 16, 17 and 18 post-inoculation and their tumours were resected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for IL-10 detection. To block the bioactivity of IL-10 we used three groups of six C57BL/6 mice, two of them were inoculated with B16-10 cells and the other was inoculated with B16-0 cells. At day 11 post-inoculation, 2 days before tumour development started in B16-10 groups, one of these groups was treated intraperitoneally with 3 µg neutralizing antibody (anti-IL-10; Zymed Laboratories, Inc.; San Francisco CA). The other B16-10 group and the group inoculated with B16-0 cells were treated only with PBS. All groups of mice were treated (with antibody or PBS) for 7 days and killed on day 18. Tumours were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and destined for immunohistochemical and morphometric analysis. Experiments were performed three times.

Detection of IL-10 in tumour tissue and cell culture supernatants

Total protein from frozen tumour tissues was isolated using trizol (Gibco-BRL). Briefly, 0·3 g tissue was pulverized after a liquid nitrogen bath and suspended in 1 ml of trizol to which 200 µl chloroform was added, then the mixture was shaken vigorously for 15 seconds followed by centrifugation at 12000 g for 10 min at 4°. Protein was isolated from the phenol–ethanol supernatants obtained after ethanol (0·3 ml) precipitation of DNA. Then the supernatants were dialysed against three changes of 0·1% sodium dodecyl sulphate at 4°, the dialysed solution was centrifuged at 10000 g for 10 min and the upper phase was collected (1 ml). On the other hand, IL-10-transfected and non-transfected B16-melanoma cells were cultured in six-well plates at an initial density of 2 × 106 cells/well in 5 ml of serum-free DMEM. Supernatants were removed after 48 hr, and proteins were quantified.21 Supernatants of cultured cells and tumour extracts were standardized with protein concentration and the IL-10-protein level was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Endogen ELISA Kit, Worburn, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. A standard curve was performed using a lyophilized Escherichia coli-derived recombinant-mouse IL-10 (Endogen ELISA Kit; Worburn, MA). Results are expressed as pg/ml of IL-10/2 × 106 cells/48 hr or pg/ml of IL-10/0·3 g of tissue.

Immunohistochemical staining and morphometric analysis

For morphometric analysis one part of the tumour tissue was fixed in absolute ethanol for 24 hr. Then the tumours were embedded in paraffin and sectioned. Sections of 5-µm thickness were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The percentage of necrosis was determined with a Zidas image analyser.22 For immunohistochemistry 5-µm sections from a frozen tumour were obtained with a Microm HM50-N-Cryostat. The sections were fixed with acetone for 3 min/at −20° and washed twice with PBS at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 6% H2O2 in methanol for 40 min. Then the slides were washed three times at 33·5 g with PBS and incubated with universal blocking reagent (Dako Corp., Carpinteria, CA) for 10 min at room temperature. Excess blocking reagent was drained, each slide was incubated for 10 min at room temperature with mouse monoclonal antibodies against Von Willebrand factor (Dako Corp.), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, CA), MHC-I (kindly provided by Dr Vianey Ortiz CINVESTAV IPN, Mexico D.F) and MHC-II (provided by Dr Leopoldo Flores CINVESTAV IPN, Mexico D.F), or rat monoclonal antibody against macrophage antigen (Mac-1; Serotec; Raleigh NC). Polyclonal antibodies made in goat and rabbit were used to detect IL-10 and IL-10 receptor (IL-10R), respectively (Vector Laboratories; Burlingame CA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies were detected with a biotinylated anti-mouse made in rabbit, rat monoclonal antibodies with a biotinylated anti-rat made in mouse and polyclonal antibodies were detected with biotinylated horse anti-goat (IL-10) and goat anti-rabbit (IL-10R; Vector Laboratories), using streptavidin–peroxidase and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Sigma Chemical Co.) or aminoethyl carbazole (Zymed Laboratories, Inc.) as chromogens. The slides were counterstained with aqueous haematoxylin and mounted with permount (Zymed Laboratories, Inc.). The percentage of positive cells was determined with a computerized image analyser (Qwim Leica, Milton Keynes, UK). For all slides, except for vessels measurements, at least five fields were examined using a ×10 or ×20 objective. To determine the vascularization of the tumours, the total surface area of the neoplastic tissue was determined in the tissue slide by automated image analysis (Qwin Leica). Then, the surface area of the blood vessels, including the lumens, was measured in the whole tumour surface of the tissue slide, and the percentage of this vascular area related to the total surface of the tumour was determined. Three tissue slides were examined for each mouse and a representative experiment is shown.

Flow cytometry analysis

Individual tumours (0·3 g) were dissociated with 5 ml of 0·1% dispase (Gibco-BRL) for 30 min at 37°. The dissociated cells were removed by gentle aspiration and placed into an equivalent volume of RPMI-1640. Fresh prewarmed enzyme solution was added again to the partially dissociated tumour and this procedure was repeated twice. Cells were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS and sieved repeatedly to remove tissue fragments and debris, yielding a homogeneous cell suspension. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 20 µl of PBS with phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD4 and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD8 (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) for 15 min at 4° (antibodies were used at 2 µg/ml). Then, the cells were washed and analysed using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose CA) to determine the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated independently at least three times. Representative experiments are shown. All in vivo experiments were performed three times. For IL-10 and nitrite concentrations, optical density (OD) units and percentages of immunohistochemical and morphological signals, the results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean of (n) observations. A t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used, as appropriate, to assess the significance of differences on IL-10 concentration, OD units and percentages of immunohistochemical and morphological signals among the groups. The associations of tumour growth with time or IL-10 concentration, and of cell proliferation with IL-10 concentration were measured by linear regression. The significance of differences of tumour growth and IL-10 curves among the cell lines was assessed by a two-way analysis of variance (anova). Differences were considered significant at a level of P < 0·05. Statistical analysis was accomplished with the sigma-stat software.

Results

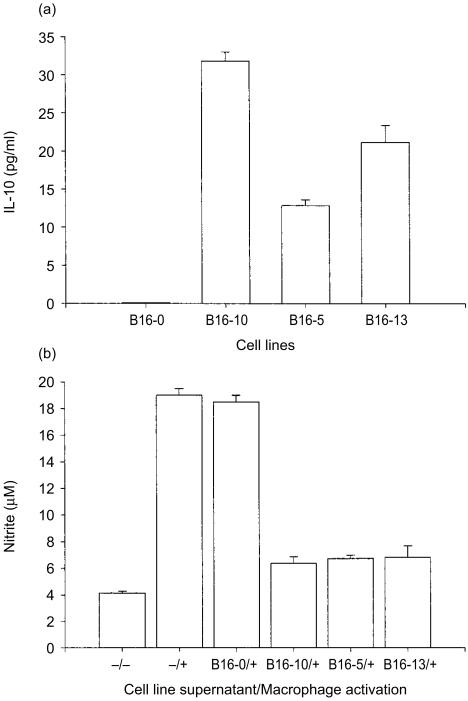

IL-10-transfected B16-melanoma cell lines produce biologically active IL-10

The B16-melanoma cell line was transfected with pcDNA3 containing IL-10 cDNA and the production of IL-10 was quantified from cell culture supernatants by ELISA. Three clones that secreted high (B16-10), medium (B16-13) and low (B16-5) amounts of IL-10 were selected (Fig. 1a). The non-transfected B16 cell line (B16-0) did not secrete IL-10. The biological activity of the secreted IL-10 was determined measuring the nitrite (NO2) concentrations after macrophage activation by LPS/IFN-γ. In comparison with the non-transfected cells, the NO2 production was inhibited in about 85% by the supernatants of the three IL-10-transfected cell lines (Fig. 1b). The inhibition of NO2 synthesis was similar and apparently did not correlate with the amount of IL-10 secreted by the different cell lines (data not shown). This experiment indicated that the three IL-10-transfected cell lines secreted enough biologically active IL-10 protein to block macrophage function.

Figure 1.

Concentration and activity of IL-10 secreted by IL-10-transfected B16-melanoma cell lines. The B16-melanoma cell line was transfected with IL-10 cDNA and the production of IL-10 was quantified from cell culture supernatants by ELISA. Three clones that secreted high (B16-10), medium (B16-13) and low (B16-5) amounts of IL-10 were selected. Results are expressed in pg/ml of IL-10/2 × 106 cells/48 hr. The biological activity of the secreted IL-10 was determined by measuring the nitrite (NO2) concentrations after macrophages were incubated with cell line supernatants and then activated by LPS/IFN-γ (see Material and Methods). Labels at the left of the slash indicate the cell-line supernatant and the sign ‘−’ indicates not incubated with cell-line supernatant; ‘+’ or ‘−’ signals at the right of the slash indicate activation or not activation of macrophages. The bar representing the nitrite basal production by macrophages is indicated as ‘−/−’ (no cell line supernatant/not activated) and total nitrite production after stimulation is indicated as −/+ (no cell line supernatant/activated). The mean of triplicates is presented and error bars represent the standard errors of means.

IL-10-transfected cells grew faster than non-transfected B16-melanoma cells in vivo

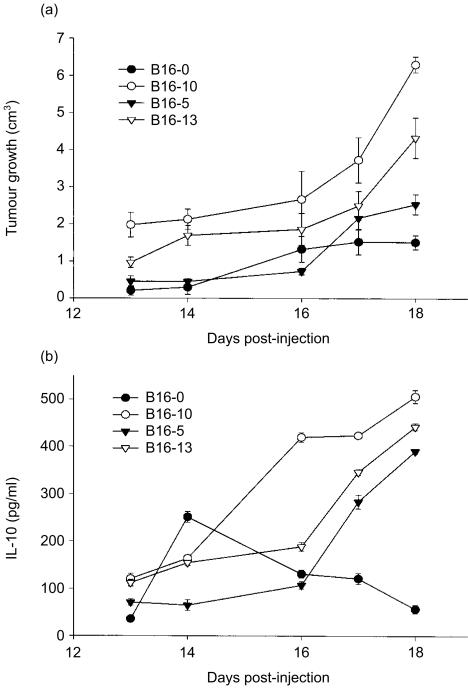

To assess the tumorigenicity and growth rate of IL-10-transfected cells, mice were challenged subcutaneously with 3 × 105 tumour cells and tumour volumes were measured over 18 days. The tumour growth of both IL-10-transfected and non-transfected B16 melanoma cells increased progressively with time (r ≥ 0·63, P < 0·001), reaching its maximum mean size at day 18 (Fig. 2a). The tumour growth of cells that secrete high (B16-10) and medium (B16-13) amounts of IL-10 was greater than that of the non-transfected control cells (P < 0·001, anova; Fig. 2a). The tumour growth of the B16-5 cell line, that secreted the lower amount of IL-10, was similar to that of non-transfected cells (P = 0·05, anova), and it was only on the last day of the experiment that it became significantly greater (P = 0·014, t-test; Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

Growth and IL-10 production of tumours generated with IL-10-transfected and non-transfected B16-melanoma cells. (a) Groups of 14 mice were injected subcutaneously with 3 × 105 cells from clones that secreted high (B16-10), medium (B16-13) and low (B16-5) amount of IL-10 or from non-transfected B16-melanoma cell line, and the tumour growth was measured by 18 days in six animals per group. IL-10 was determined by ELISA assay in tumour samples obtained from two mice of each group, killed at days 13, 14, 16, 17 and 18. Results are expressed in pg/ml of IL-10/0·3 g of tumour tissue (see Materials and Methods). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean in one representative experiment.

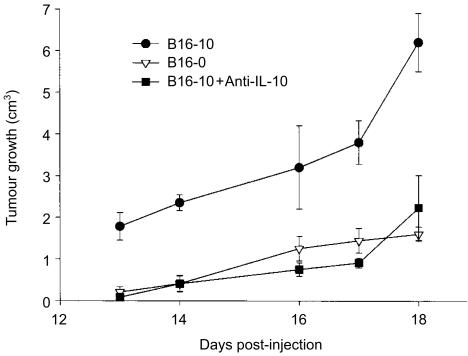

The production of IL-10 was measured by ELISA in the tumours' homogenates at days 13, 14, 16, 17 and 18. IL-10 was detected in tumours derived from transfected and non-transfected cells, however, only in the former did the IL-10 concentration increase linearly with time (r ≥ 0·91, P < 0·001; Fig. 2b), reaching its maximum level at day 18 (B16-10, 498 ± 4·5; B16-13, 438 ± 2·5 and B16-5, 391 ± 4·4 pg of IL-10/0·3 g of tissue). Although in the supernatants of non-transfected cells the IL-10 was not detected, in tumours generated with this cell line (B16-0), IL-10 was detected from day 13 (32 ± 1·0 pg), reaching its peak at day 14 (259 ± 3·0 pg) and then decreased towards day 18 (62 ± 4·0 pg; Fig. 2b). The difference in IL-10 production between tumours developed with IL-10-transfected and non-transfected cell lines was statistically significant (P < 0·001; anova). Interestingly, tumour growth correlated with the increase of IL-10 concentration in tumours generated with the transfected cell lines B16-10 (r = 0·79, P = 006), B16-5 (r = 0·99, P < 0·001) and B16-13 (r = 0·94, P < 0·001), but not in tumours generated by the non-transfected cell line (r = 0·22, P = 0·55), and tumours that grew faster were those that contained the highest amount of IL-10 (Fig. 2). To confirm that the enhanced tumour growth was exerted by IL-10 secretion, the tumour growth of the highest IL-10-producer cells (B16-10) was explored in mice treated with an IL-10-neutralizing antibody. In these mice, the tumours grew slower than in control mice (P < 0·001, anova), and behaved in a similar way to those induced by non-transfected tumour cells (Fig. 3), confirming that IL-10 secreted by transfected cells is actually promoting the tumour growth in this melanoma-B16 model.

Figure 3.

Tumour growth of IL-10-transfected B16-melanoma cells in mice treated with anti-IL-10 antibody. Three groups of six C57BL/6 mice were used in this experiment, two of them were inoculated with B16-10 cells and the other was inoculated with B16-0 cells. At day 11 post-inoculation, 2 days before tumour development started in B16-10 groups, one of these groups was treated with 3 µg of neutralizing antibody (anti-IL-10). The other B16-10 group and the group inoculated with B16-0 cells were treated only with PBS. All groups of mice were treated (with antibody or PBS) for 7 days, tumour growth was measured every day and mice were killed at day 18. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of one representative experiment.

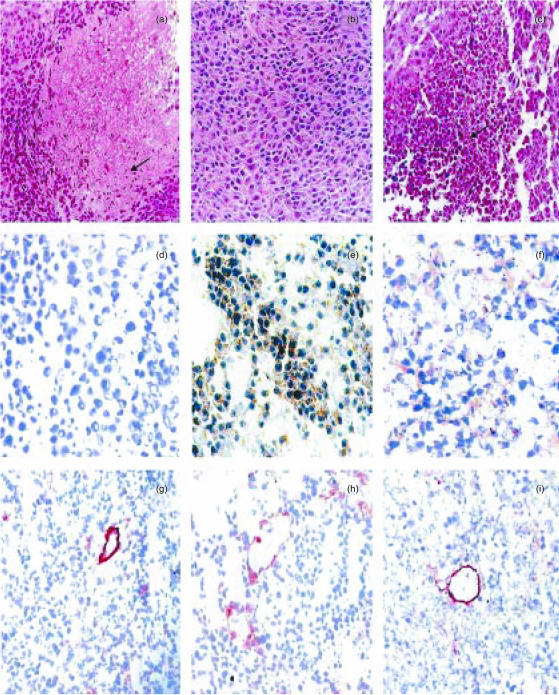

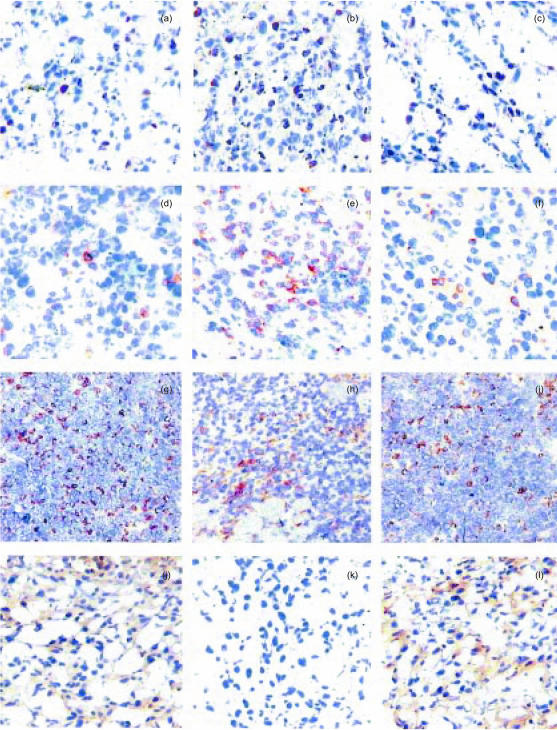

The cellular origin of the IL-10 was investigated by immunohistochemistry. In tumours generated by the IL-10-transfected cells (B16-10), this cytokine was detected in both tumour and inflammatory infiltrating cells (Fig. 6e), whereas in tumours produced by the non-transfected cell line (B16-0), the tumoral cells were negative for IL-10 (Fig. 6d) and IL-10 immunostaining was observed only in tumour-infiltrating macrophages (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Histological and immunohistochemical comparisons in tumours produced after 18 days of melanoma cell inoculation. (a) Non-transfected tumours have extensive areas of ischaemic necrosis, characterized by picnotic nuclei (arrow) surrounded by deep acidophilic cytoplasm. (b) In contrast, IL-10-transfected tumours do not have necrotic areas. (c) Necrotic areas are produced when the activity of IL-10 is suppressed using blocking antibodies in animals bearing transfected tumours. (d) There is not IL-10 immunoreactivity in tumoral non-transfected cells. (e) In contrast, the majority of neoplastic transfected cells show strong IL-10 immunostaining. (f) Many transfected neoplastic cells have cytoplasmic IL-10 immunoreactivity after administration of IL-10-blocking antibodies. (g) The immunohistochemical detection of Von Willebrand factor as a marker of endothelial cells, shows fewer blood vessels in non-transfected than in IL-10-transfected tumours (h). (i) When mice bearing IL-10-transfected tumours are treated with blocking anti-IL-10 antibodies, the number of blood vessels is similar to that in non-transfected tumours. (All micrographs ×100, except panels d–f, ×200).

IL-10 increased cell proliferation in vitro and tumour growth in vivo by a direct autocrine stimulation of B16-melanoma cells

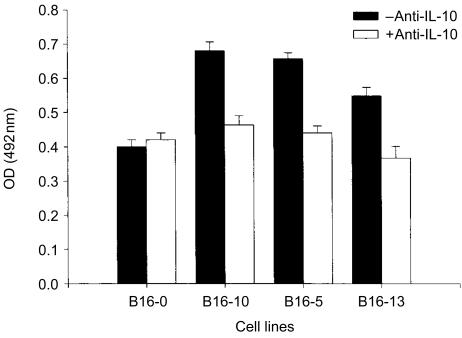

It has been shown that IL-10 can be an autocrine growth factor.18 Cell proliferation of IL-10-transfected and non-transfected cells was measured in vitro to explore the possibility that IL-10 could induce cell proliferation in an autocrine manner. Consistent with the in vivo results, the three transfected cell lines (B16-10, B16-5 and B16-13) grew faster than the control non-transfected cells (B16-0; P < 0·01, t-test). This effect was reversed by the addition of a neutralizing anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 4). In fact, there was a dose-dependent effect between the amount of IL-10 produced and the increase in cellular proliferation (r = 0·82, P = 0·014). These results indicated that IL-10 secreted in supernatants stimulated the cellular proliferation of B16-melanoma cells in vitro via an autocrine mechanism.

Figure 4.

Cell proliferation of IL-10-transfected and non-transfected B16-melanoma cells. Cell line proliferation was measured by the incorporation of BrdU with a colorimetric method. Cell lines (1440 tumour cells/well) were cultured in triplicates for 24 hr, then treated only with culture medium or 3 µg/ml of IL-10-neutralizing antibody for 48 hr. Cells were then labelled by the addition of BrdU for 5 hr and incorporation of BrdU was quantified by a colorimetric reaction measuring the absorbance at 370 or 492 nm (see Materials and methods). The mean OD of triplicates is presented and bars represent the standard error of means.

The proliferation activity of tumour cells in vivo was indirectly measured by the detection and quantification of the PCNA by immunohistochemistry and automated image analysis (Fig. 5a–c). The percentage of tumour cells positive for PCNA was 4·4-fold higher in B16-10 (Fig. 5b) than in B16-0 (Fig. 5a) tumours (29·7 ± 3% versus 6·8 ± 1·2%; P < 0·001, Mann–Whitney U-test). The number of PCNA-positive cells in B16-10 tumours of mice treated with anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody (7·9 ± 1·7%; Fig. 5c) was similar to that of B16-0 tumours (Fig. 5a). These data confirm that IL-10 promotes tumour cell proliferation in vivo.

Figure 5.

Representative immunohistochemical features in tumours produced after 18 days of melanoma cell inoculation. (a) Non-transfected tumours have occasional cells with nuclear immunoreactivity to PCNA. (b) In contrast, IL-10-transfected tumours have numerous PCNA-positive cells denoting a higher proliferative activity. (c) The administration of IL-10-blocking antibodies in transfected tumour-bearing mice significantly reduced the number of PCNA-positive cells. (d) Occasional neoplastic cells have immunoreactivity to IL-10R. (e) In comparison, numerous cells are IL-10R-positive in transfected tumours. (f) Animals bearing IL-10-transfected tumours treated with blocking antibodies have scarce IL-10R-positive cells. (g) Non-transfected tumours have many infiltrating macrophages (× 100). (h) Macrophages are usually settled in the periphery of the IL-10-transfected tumours (× 100). (i) A similar number and distribution of macrophages as in non-transfected tumours is observed in IL-10-transfected tumours treated with blocking antibodies (× 100). (j) The majority of neoplastic cells have MHC-I molecules in non-transfected tumours.(k) In contrast, occasional cells are MHC-I positive in IL-10-transfected tumours. (l) Many neoplastic cells express MHC-I molecules in IL-10-transfected tumours after the administration of blocking antibodies. (All micrographs ×200, except panels g–i).

To support the hypothesis that the induction of tumour-cell proliferation in our experimental model is an autocrine mechanism, the expression of IL-10R was determined in neoplastic cells by immunohistochemistry and computerized image analysis (Fig. 5d–f). The IL-10R was detected in approximately 20% of B16-10 tumour cells (Fig. 5e) and in only 1·2 ± 0·8% of B16-0 tumour cells (Fig. 5d; P < 0·001, t-test). The percentage of positive cells for IL-10R decreased to 4·7 ± 0·95% in B16-10 tumours of mice treated with anti-IL-10 (Fig. 5f). These data suggest that IL-10 secretion induced the expression of IL-10R and enhanced tumour growth by an autocrine mechanism.

IL-10 impairs the recruitment of macrophages and increases CD4+ cells in the tumour environment, and decreased MHC-I expression in tumour cells

Several reports have shown that IL-10 is able to deactivate macrophage functions,5 and down-regulates the expression of antigen-presenting molecules.10,23 To determine whether IL-10 impaired the local immune response in this melanoma model, the presence of macrophages and the expression of MHC-I and -II molecules were explored by immunohistochemistry and the presence of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes was determined by FACS. In non-transfected tumours, macrophages were diffusely distributed in the whole lesion, comprising 6·4 ± 1·7% of the total cell population (Fig. 5g). In contrast, in IL-10-transfected tumours macrophages were located in the periphery, and they comprise only 3·8 ± 1·7% of the whole cell population (Fig. 5h). In B16-10 tumours of mice treated with the neutralizing antibody, the percentage (5·3 ± 1·5%) and distribution pattern of macrophages were similar to those of B16-0 tumours (Fig. 5i). On the other hand, the presence of CD4+ lymphocytes was 7·6 times higher in B16-10 than in B16-0 tumours (4·4 ± 0·61 versus 0·58 ± 0·38%; P = 0·002, t-test). Interestingly, in B16-10 tumours of mice treated with anti-IL-10 the percentage of CD4+ lymphocytes decreased only to 3·1 ± 1·0%. This suggests that once migration of CD4+ cells was induced, it was not completely inactivated by neutralization of IL-10. The percentage of CD8+ lymphocytes was similar in both B16-10 and B16-0 tumours (0·73 ± 0·42 versus 0·39 ± 0·22%, respectively; P = 0·5, t-test), suggesting that they are not activated by IL-10 in this B16-melanoma model.

The expression of MHC class I molecules was quite different in B16-10 and B16-0 tumours. Whereas in B16-0 tumours all tumour cells expressed MHC-I molecules (Fig. 5j), the expression of these molecules was completely negative in B16-10 tumours (Fig. 5k). There was not a major difference in MHC-II expression between B16-10 and B16-0 tumours.

IL-10 decreased necrosis and induced angiogenesis in this B16-melanoma tumour model

Thirteen days after B16-0 tumour cell inoculation, sheets of large polyhedric neoplastic cells with large nuclei and extended chromatin were located in the subcutaneous tissue. These cells clearly infiltrated the adipose and muscular tissue 16 days after inoculation, inducing slight mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the tumour borders and small focal inflammatory patches in the centre of the tumour, with extensive and progressive areas of ischaemic necrosis. These devitalized areas reached a peak at the end of the experiment (18 days post-inoculation) when 89 ± 4% of the whole tumour area was necrotic (Fig. 6a). In sharp contrast, the subcutaneous tumours produced by the IL-10-transfected melanoma line (B16-10) showed only 4·3 ± 6% necrotic areas after 18 days of inoculation (Fig. 6b). The blood-vessel surface area, as determined by the immunohistochemistry detection of the endothelial marker Von Willebrand factor and automated morphometry, was inversely correlated with the extension of necrotic tissue, showing that IL-10-transfected tumours had 17-fold more surface occupied by blood vessels than the non-transfected tumours (61·8 ± 8% versus 3·5 ± 1·7% blood-vessel surface; P < 0·001, t-test; Fig. 6g,h). This angiogenic effect was IL-10 dependent since mice bearing IL-10-transfected tumours and treated with blocking antibodies against IL-10 showed 76·9 ± 19% necrotic areas (Fig. 6c), and almost the same blood-vessel surface area as the non-transfected tumours (Fig. 6i). In addition, isolated endothelial cells were detected much more frequently in B16-10 than in B16-0 tumours. The presence of isolated endothelial cells indirectly suggests an active neovascularization process. Furthermore, numerous endothelial cells comprising well-defined blood vessels were strongly IL-10R immunostained. These results strongly suggest that IL-10 promotes angiogenesis in our model, favouring the survival of fast-proliferating tumour cells and protecting them from the iscaemic necrosis observed in B16-0 tumours.

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that IL-10 induces tumour growth of B16-melanoma cells in the syngeneic C57BL/6 mouse, which directly correlated with the amount of IL-10 secreted by tumour cells. The increase of tumour growth by IL-10 could be induced by at least three different simultaneous mechanisms: direct stimulation of cell proliferation through an autocrine mechanism, induction of angiogenesis, and the suppression of the local immune system. Although this study did not investigate which of these mechanisms is more important in the induction of tumour growth in vivo, in this model it seems clear that the three mechanisms are promoting tumour growth.

Suppression of the immune response is the main mechanism proposed by which IL-10 could promote tumour growth in human tumours and murine models.14,15 In our model, the decreased macrophage number in tumour infiltrates and decreased expression of MHC-I molecules in tumour cells suggest that stimulation of CTLs through the antigen-presenting route is absent or diminished. These data are consistent with the fact that infiltrates of CTLs were similar in IL-10-transfected and non-transfected tumours, and are in agreement with the previous demonstration that IL-10 promotes lung cancer growth by suppressing both T-cell and APC functions.15 Interestingly, we also found that IL-10 induces the infiltration of T-helper lymphocytes, if these cells are of the Th2 type this could also favour tumour growth.

In several in vitro models, IL-10 may inhibit different immune mechanisms involved in the anti-tumour response (Table 1). However, in mouse models the effects of IL-10 on the anti-tumour immune response is controversial. In some models, IL-10 inhibits the tumoral growth by stimulation of immune system, mostly CTLs and NK cells. In other models, the IL-10 promotes the tumoral growth through a local immunosupression, inhibiting APC functions, CTLs and the Th1 response (Table 2). This apparent contradiction might be explained by differences in IL-10-mediated outcomes due to concentration-dependent effects.15 For example, the reports from Giovarelli et al.,17 Gerard et al.30 and Kundu et al.32,33 showed IL-10-mediated tumour reduction in transfected murine tumours producing 2000, 20–400 and 100–200 ng/ml of IL-10/106 cells/48 hr, respectively (Table 2). Consistent with these results, the tumour growth is inhibited in mice treated systemically with IL-10 at serum concentrations around 500–1000 ng/ml40 (Table 2). These cytokine levels are not comparable with the amounts of IL-10 secreted by tumours or tumour cell lines (0·04–5 ng/ml30), and thus may be expected to have different effects. These findings appear to be consistent with the fact that IL-10 has been shown to be a positive factor for T-cell differentiation, chemoattraction and co-stimulation, being a survival factor for IL-2-deprived T cells.11,12,41–43 In tumour models where IL-10 suppresses the immune response and increases tumour growth, the production of IL-10 is much lower.15,36,39 In contrast to the studies of Giovarelli et al., Gerard et al. and Kundu et al., in our B16-melanoma model, tumour cells in vitro produced 0·016 ng/ml of IL-10/106 cells/48 hr and in vivo (18 days post-inoculation) they produced 1·6 ng/ml of IL-10/g tumour tissue. These quantities are similar to that observed in those models where the IL-10 induces the tumour growth (Table 215,36,39). Thus, while recent studies indicate that high-level production of IL-10 from transduced tumours promotes tumour regression, the results found by some authors15,36,39 and in the present model, indicate that physiological levels of IL-10 inhibit anti-tumour immunity and favour tumour growth. As suggested by Suzuki et al.,29 when IL-10 is expressed at very high local concentrations in transfected tumours, the stimulatory effects on T cells may obscure the immunosuppressive effects on antigen-presenting and accessory cell functions of dendritic cells and macrophages. Cytokines may have opposite effects depending on their local concentration and similar duality of effects has already been reported for other cytokines, i.e. TNF-α,44 granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor,45,46 or transforming growth factor-β.47

Table 1. Effects of IL-10 on the interactions of immune and tumour cells in vitro.

| Immune/tumour cells | IL-10 (ng/ml) | Effects of IL-10 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human monocytes and alveolar macrophages*/A375 | 1–10 | Suppression of the cytotoxicity of monocytes and macrophages | 24 |

| Tumour-specific CTLs/DL mel, KH mel, RMA† | 5–20‡ | Protects target cells from lysis by tumour-specific cytotoxic T cells Down-regulates HLA class I expression | 23,25 |

| Human mature Langerhans cells§ | 1–10 | Promote dendritic cell apoptosis | 26 |

| CTL¶/5T RFM | 0·05–0·06‡ | Inhibit tumour CTL cytotoxicity and IFN-γ secretiony stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ cells | 27 |

| TIL/Human cutaneous basaland squamous carcinomas** | 0·6–1·8‡ | Suppressed the TIL proliferative response to autologoustumour cells | 14 |

| Murine macrophages††/C-26 | 0·08‡ | Suppression of tumour-associated macrophages | 28 |

A375, human melanoma, Dlmel and Khmel, human melanoma, RMA, murine lymphoma, 5T RFM, murine lymphoma, C-26, colon carcinoma.

Immune cells were pretreated with IL-10

IL-10 produced by transfected tumour cells or tumour cells pretreated with exogenous IL-10.

IL-10 concentration was adjusted to 1×106 cell/ml/48 hr.

IL-10 added to the culture medium

Non-cytotoxic CD8+ T cells secrete IL-10 spontaneously.

Tumour cells secrete IL-10 spontaneously.

IL-10 produced by infiltrating macrophages.

Table 2. Influence of IL-10 on tumoral growth in immunocompetent mice.

| Model | Tumour cells | IL-10 (ng/ml)* | Tumour growth | Effects of IL-10 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal models with tumour cells transfected with IL-10 or that spontaneously produce IL-10 | |||||

| BALB/c | TSA | 2000† | D | Tumour inhibition depends on the induction oftumour-specific CTLs, and activation of PMN and NK cells | 17 |

| C57BL/6 | CL8–1 | 51† | D | Tumour infiltration by CD4+ and CD8+lymphocytes was markedly increased | 29 |

| C57BL/6 | B16 | 20–400† | D | Induces important anti-tumour response by CTLs and natural killer cells | 30 |

| C57BL/6 | B16, M27 | 12–500† | D | Inhibits tumour metastasis through an NK cell-dependent mechanism. Found absence of CD8+, CD4+ and macrophages, and abundant NK cells | 31 |

| BALB/c | 410·4, 66·1 | 100–120† | D‡ | Stimulate T-cell and NK activities. Down-regulates MHC class I expression | 32,33 |

| C57BL/6 | MCA 203 and 205 | 17† | D | Mononuclear cellular infiltrate. Induced anantigen-specific immune response | 34 |

| BALB/c | WP4 | 70–90 U/ml† | I | Produced local immunosupression and preventedCTL alloreactivity by inhibition of CD4+,dendritic cells and macrophages | 35 |

| BALB/c | J558L§ | 5† | I | Limit access of dendritic cells (DC) to the tumour site | 36 |

| C57BL/6 | B16 | 0·016†1·6 ng/gm¶ | I | Reduced tumour-infiltrated macrophages andMHC-I molecules expression on tumour cells. Increase CD4+ cells. Induced autocrine cell proliferation and angiogenesis | present paper |

| Animal models with IL-10-transgenic mice, with tumour cells inducing tumour-infiltrating cells to produce IL-10 or with mice treated systemically with IL-10 | |||||

| DBA2×BALB/c, MHC-II promoter | P815 | 0·4–0·7** | I/D | Activation of CTLs | 37 |

| 1·2†† | |||||

| C57BL/6, IL-2 promoter | 3LL | 1·7–2·4†† | I | Prevents the development of an effective immune response against tumour cells | 38 |

| C57BL/6, IL-2 promoter | 3LL | 0·4†† | I | Suppression of T cell and APC functions | 15 |

| 14·8 ng/gm¶ | |||||

| C57BL/6 | MB49‡‡ | 1·2‡‡ | I | Can block the generation of a tumour specific Th1 immune response | 39 |

| C57BL/6 | MCA207,MC38,CL8–1 | 500–1000§§ | D | Stimulate the acquisition of an effective, specific,and long-lived anti-tumour immune response | 40 |

D, decreased or inhibited; I, increased; TSA, murine mammary adenocarcinoma, CL8-1, BL6/H-2Kb; B16, murine melanoma; M27 and 3LL, Lewis murine lung carcinoma; 410·4 and 66·1, murine mammary tumour; MCA203 and 205, murine sarcoma; WP4, murine fibrosarcoma; J558L, plasmacytoma; P815, murine mastocytoma; MB49, murine bladder tumour; MCA207, murine sarcoma; MC38, colon adenocarcinoma.

IL-10 is expressed in ng/ml, except in those lines indicating other units.

IL-10 was measured in the supernatant of cultured tumour cells, and to be compared, the data obtained from the papers were adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml/48 hr.

Decreased tumour growth and metastasis.

Produces IL-10 constitutively.

IL-10 measured on tumour tissue.

IL-10 measured in animal serum.

IL-10 measured on splenic T-cell supernatants.

Tumour cells induce infiltrating cells to produces IL-10, and measurement of IL-10 come from single cell suspensions derived from tumours, and it was adjusted to 1×106 cells/ml/48 hr.

Mice were treated with 20–40 µg of IL-10/kg intraperitoneally. Concentration of IL-10 in serum was calculated considering the mice to weigh 25 g, 1 ml of serum and assuming that all injected IL-10 reaches the blood circulation.

The autocrine stimulation of cell proliferation by IL-10 has been previously observed in other cell lines, such as human melanoma18 and myeloma cells.19 However, its role in vivo has not been demonstrated. Induction of B16-melanoma cell proliferation by IL-10 through the autocrine route was clearly demonstrated in this paper by employing in vitro experiments. In addition, the autocrine stimulation of cellular growth was partially demonstrated in vivo. Progressive induction of the IL-10R on tumour cells in vivo strongly suggests that IL-10 stimulates tumour growth in an autocrine manner. The progressive increase of PCNA clearly indicates that IL-10 stimulates cell proliferation of B16-melanoma cells. However, this observation does not indicate whether cell growth is promoted by autocrine stimulation, immune system suppression, or by the vascular proliferation.

In this melanoma-murine model extensive tumour necrosis is produced during malignant growth of IL-10 nontransfected cells. Hypoxia and cell death is a common feature inside solid tumours. Necrosis could happen only because the rate of growth in this solid tumour outstrips the supply of oxygen to the cells. However, important macrophage infiltrates may play an integral role in determining necrosis severity, especially by TNF-α secretion. Another factor that might be contributing to the necrosis in this murine melanoma model is the poor blood-vessel formation. Indeed, the type of necrosis observed in this murine melanoma model by histopathology was typically ischaemic, apparently as a consequence of insufficient blood-vessel formation. IL-10, a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, may prevent necrosis in the transfected tumours by the inactivation of macrophages, avoiding the release of inflammatory cytokines, in a similar fashion to that in experimental murine pancreatitis.48 The other way that IL-10 could prevent necrosis is by induction of vessel proliferation.

In the present model, IL-10 strongly stimulated blood-vessel growth. Tumour angiogenesis is believed to be induced by increased production of angiogenic factors and decreased production of angiogenic inhibitors by cancer cells, vascular endothelial cells, and other stromal and inflammatory cells. Macrophages have an essential role in tumour angiogenesis.49,50 The important presence of macrophages and the low vascularity in IL-10 non-transfected B16-melanoma tumours suggest that in this context macrophages are inhibiting angiogenesis. In this model we clearly demonstrated that IL-10 diminished macrophage infiltration at the same time as it increased CD4+ lymphocytes and induced angiogenesis. The stimulation of vascular proliferation in the tumour bed by IL-10 has not been described previously. Rather, it was observed that IL-10 inhibits angiogenesis in several tumour models employing immunodeficient mice2,16,51,52 or in an in vitro angiogenesis model.53 In the present model, vessel proliferation could be essentially induced by inactivation of macrophages or by direct stimulation of the endothelial cells. We do not know whether endothelial proliferation is directly induced by IL-10 or if it is stimulated through a mediator induced by this cytokine. Immunohistochemistry for the Von Willebrand factor and IL-10 receptor showed positive immunostaining on the blood vessels (data not shown), which suggests that IL-10 could induce vascular growth through a direct paracrine effect over the vascular endothelium. On the other hand, the great increase of CD4+ lymphocytes in IL-10-transfected tumours generated in C57BL/6 mice is an important difference with tumour models that employ immunodeficient animals.2,16,51,52 Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the CD4+ cells may have a modulatory role in tumour angiogenesis. Irrespective of the molecular mechanism in the present tumour model it seems clear that IL-10-promoted angiogenesis strongly induces tumour growth.

Macrophages appear to have a central role in the immune response, the necrosis process and angiogenesis observed in this tumour model. Thus, both inhibition of macrophages by IL-10 and direct autocrine and paracrine effects of IL-10 may explain the actions that induce tumour growth in this B16-melanoma model.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Secretariat of National Defence of Mexico, National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT) grants numbers L0036-M9607 (to J.B.) and M0205 (to J.B. and P.G.).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cells

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxy-uridine

- CTL

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- DC

dendritic cells

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- ICAM

intracellular adhesion molecules

- IFN-γ

interferon-γ

- IL

interleukin

- IL-10R

interleukin-10 receptor

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- NK

natural killer

- OD

optical density

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PE

phycoerythrin

- rIL-10

recombinant IL-10

- TGF-β

tumour growth factor-β

- Th

T helper

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor-α.

References

- 1.Salazar-Onfray F. Interleukin-10: a cytokine used by tumors to escape immunosurveillance. Med Oncol. 1999;16:86–94. doi: 10.1007/BF02785841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stearns ME, García FU, Fudge K, Rhim J, Wang M. Role of interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in the angiogenesis and metastasis of human prostate primary tumor lines from orthotopic implants in severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Cancer Res. 1999;5:711–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Vita F, Orditura M, Galizia G, Romano C, Lieto E, Iodice P, Tuccillo C, Catalano G. Serum interleukin-10 is an independent prognostic factor in advanced solid tumors. Oncol Rep. 2000;7:357–61. doi: 10.3892/or.7.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosmman TR. Interleukin−10. In: Thomson A, editor. The Cytokine Handbook. London: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 223–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mossman TR, Howard M, O'Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosmman T, Moore KW. The role of IL-10 in cross-regulation of Th1 and Th2 responses. Immunol Today. 1991;12:A49–53. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Garra A, Stapleton G, Dhar V, et al. Production of cytokines by mouse B cells: B lymphomas and normal B cells produce IL-10. Int Immunol. 1990;2:821–32. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.9.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Vieria P, Mossman TR, Howard M, Moore KW, O'Garra A. IL-10 acts on the antigen-presenting cell to inhibit cytokine production by Th1 cells. J Immunol. 1991;146:3444–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taga K, Mostowski H, Tosato G. Human interleukin-10 can directly inhibit T-cell growth. Blood. 1993;81:2964–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, et al. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. J Exp Med. 1991;174:915–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeil IA, Suda T, Moore KW, Mosmann TR, Zlotnik A. IL-10, a novel growth cofactor for mature and immature T cells. J Immunol. 1990;145:4167–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen WF, Zlotnik A. IL-10: a novel cytotoxic T cell differentiation factor. J Immunol. 1991;147:528–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Go NF, Castle BE, Barret R, Kastelein R, Dang W, Mosmann TR, Moore K, Howard M. Interleukin 10, a novel B cell stimulatory factor: unresponsiveness of X chromosome-linked immunodeficiency B cells. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1625–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Modlin RL, Moy RL, Dubinett SM, McHugh T, Nickoloff BJ, Uyemura K. IL-10 production in cutaneous basal and squamous cell carcinomas. A mechanism for evading the local T cell immune response. J Immunol. 1995;155:2240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma S, Stolina M, Lin Y, Gardner B, Miller PW, Kronenberg M, Dubinett SM. T cell-derived IL-10 promotes lung cancer growth by suppressing both T cell and APC function. J Immunol. 1999;163:5020–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang S, Xie K, Bucana CD, Ullrich SE, Bar-Eli M. Interleukin 10 suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma cells: potential inhibition of angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1969–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giovarelli M, Musiani P, Modesti A, et al. Local release of IL-10 by transfected mouse mammary adenocarcinoma cells does not suppress but enhances antitumor reaction and elicits a strong cytotoxic lymphocyte and antibody-dependent immune memory. J Immunol. 1995;155:3112–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yue FY, Dummer R, Geertsen R, Hofbauer G, Laine E, Manolio S, Burg G. Interleukin-10 is a growth factor for human melanoma cells and down-regulates HLA class-I, HLA class-II and ICAM-1 molecules. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:630–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970516)71:4<630::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu Z, Costes U, Lu ZY, et al. Interleukin-10 is a growth factor for human myeloma cells by induction of an oncostatin M autocrine loop. Blood. 1996;88:3972–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham FL, Van der EB. A new technique for the assay of infectivity of human adenovirus 5 DNA. Virology. 1973;52:456–67. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(73)90341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernández-Pando R, Pavon L, Orozco EH, Rangel J, Rook GAW. Interaction between hormone-mediated and vaccine-mediated Immunotherapy for Pulmonary Tuberculosis in BALB/c Mice. Immunology. 2000;100:391–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00054.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda M, Salazar F, Petersson M, et al. Interleukin 10 pretreatment protects target cells from tumor- and allo-specific cytotoxic T cells and downregulates HLA class I expression. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2371–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabioullin R, Sone S, Mizuno K, Yano S, Nishioka Y, Haku T, Ogura T. Interleukin-10 is a potent inhibitor of tumor cytotoxicity by human monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:437–42. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salazar-Onfray F, Petersson M, Franksson L, Matsuda M, Blankenstein T, Kärre K, Kiessling R. IL-10 converts mouse lymphoma cells to CTL-resistant, NK-sensitive phenotype with low but peptide-inducible MHC class I expression. J Immunol. 1995;154:6291–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ludewig B, Graf D, Gerderblom HR, Becker Y, Kroezek A, Pauli G. Spontaneous apoptosis of dendritic cell is efficiently inhibited by TRAP (CD-40 ligand) and TNFα, but strongly enhanced by interleukin-10. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1943–50. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohrer J, Coggin JH. CD8 T cell clones inhibit antitumor T cell function by secreting IL-10. J Immunol. 1995;155:5719–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kambayashi T, Alexander HR, Fong M, Strassmann G. Potential involvement of IL-10 in suppressing tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;154:3383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuki T, Tahara H, Narula S, Moore KW, Robbins PD, Lotze MT. Viral interleukin 10 (IL-10), the human herpes virus 4 cellular IL-10 homologue, induces local anergy to allogeneic and syngeneic tumors. J Exp Med. 1995;182:477–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerard CM, Bruyns C, Delvaux A, Baudson N, Dargent JL, Goldman M, Velu T. Loss of tumorigenicity and increased immunogenicity induced by interleukin-10 gene transfer in B16 melanoma cells. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:23–31. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng LM, Ojcius DM, Garaud F, et al. Interleukin-10 inhibits tumor metastasis through an NK cell-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 1996;184:579–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kundu N, Beaty TL, Jackson MJ, Fulton AM. Antimetastatic and antitumor activities of interleukin 10 in a murine model of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:536–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.8.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kundu N, Fulton AM. Interleukin-10 inhibits tumor metastasis, downregulates MHC classI, and enhances NK lysis. Cell Immunol. 1997;180:55–61. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barth RJ, Coppola MA, Green WR. In vivo effects of locally secreted IL-10 on the murine antitumor immune response. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;4:381–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02305668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Goillot E, Tepper R. IL-10 inhibits alloreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte generation in vivo. Cell Immunol. 1994;159:152–69. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin Z, Noffz G, Mohaupt M, Blankenstein T. Interleukin-10 prevents dendritic cell accumulation and vaccination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor gene-modified tumor cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:770–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groux H, Cottrez F, Rouleau M, et al. A transgenic model to analyze the immunoregulatory role of IL-10 secreted by antigen-presenting cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:1723–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hagenbaugh A, Sharma S, Dubinett SM, et al. Altered immune responses in interleukin 10 transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2101–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Halak BK, Maguire HC, Lattime EC. Tumor-induced interleukin-10 inhibits type I immune responses directed at a tumor antigen as well as a non-tumor antigen present at the tumor site. Cancer Res. 1999;59:911–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berman RM, Suzuki T, Tahara H, Robbins PD, Narula AK, Lotze MT. Systemic administration of cellular IL-10 induces an effective, specific, and long-lived immune response against established tumor in mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:231–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yano S, Yanagawa H, Nishioka Y, Mukaida N, Matsushima K, Sone S. T helper 2 cytokines differently regulate monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production by human peripheral blood monocytes and alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;157:2660–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang G, Hellstrom KE, Mizuno MT, Chen L. In vitro priming of tumor-reactive cytolytic T lymphocytes by combining IL-10 with B7–CD28 costimulation. J Immunol. 1995;155:3897–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Groux H, Bigler M, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. Inhibitory and stimulatory effects of IL-10 on human CD8+T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:3188–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeyama H, Wakamiya N, O'Hara C, Arthur K, Niloff J, Kufe D, Sakarai K, Spriggs D. Tumor necrosis factor expression by human ovarian carcinoma in vivo. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4476–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fu YX, Watson GA, Kasahara M, Lopez DM. The role of tumor-derived cytokines on the immune system of mice bearing a mammary adenocarcinoma. I. Induction of regulatory macrophages in normal mice by the in vivo administration of rGM-CSF. J Immunol. 1991;146:783–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3539–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ioannides CG, Whiteside TL. T cell recognition of human tumors: implications for molecular immunotherapy of cancer. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;66:91–106. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1012. 10.1006/clin.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Laethem JL, Marchant A, Delvaux A, Goldman M, Robberecht P, Velu T, Deviere J. Interleukin 10 prevents necrosis in murine experimental acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1917–22. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ono M, Torisu H, Fukushi J, Nishie A, Kuwano M. Biological implications of macrophage infiltration in human tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol Supplement. 1999;43:S69–71. doi: 10.1007/s002800051101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis CE, Leek R, Harris A, McGee JO. Cytokine regulation on angiogenesis in breast cancer: The role of tumor-associated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:747–51. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cervenak L, Morbidelli L, Donati D, et al. Abolished angiogenicity and tumorigenicity of Burkitt lymphoma by interleukin-10. Blood. 2000;96:2568–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang S, Ullrich SE, Bar-Eli M. Regulation of tumor growth and metastasis by interleukin-10: the melanoma experience. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1999;19:697–703. doi: 10.1089/107999099313532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stearns ME, Rhim J, Wang M. Interleukin-10 (IL-10): inhibition of primary human prostate cell-induced angiogenesis: IL-10 stimulation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 and inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) -2/MMP-9 secretion. Cin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:189–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]