Abstract

A human L-selectin–ZZ fusion protein was used to screen porcine inguinal lymph nodes for the presence of monoclonal antibody (mAb) MECA 79-negative ligands. Fractionation of lymph node-conditioned medium by anion-exchange chromatography revealed two distinct L-selectin-binding fractions, one containing a MECA 79 non-reactive species and the second containing two MECA 79 reactive species of ≈84 000 and 210 000 molecular weight. The MECA 79 non-reactive species exhibited Ca2+- and lectin-dependent binding to L-selectin–ZZ in a solid-phase capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and this was specifically disrupted by the addition of EDTA, mannose-6-phosphate and the blocking anti-L-selectin mAb, DREG-56. Enzymatic characterization of the ligand by trypsin, O-sialoglycoprotease endopeptidase, heparinases I and III, or chondroitinase ABC lyase digestion indicated that L-selectin binding was predominantly dependent upon a chondroitin sulphate-modified glycoprotein determinant. Although Coomassie Blue staining of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels did not reveal a detectable protein species, carbohydrate-specific staining using GlycoTrack™ revealed a single, heavily glycosylated protein of high molecular weight (> 220 000). These studies have revealed the existence of a MECA 79 non-reactive, chondroitin sulphate glycosaminoglycan-modified ligand, termed csgp>220, which is secreted by peripheral lymph nodes and may play a role in leucocyte trafficking to the lymph node.

Introduction

The homing and recirculation of lymphocytes through lymphoid tissues constitutes an integral part of immune surveillance and defence against pathogens. Ongoing research in this area has shown that leucocyte homing is initiated under conditions of hydrodynamic shear flow by a transient rolling interaction mediated by L-selectin expressed on the surface of leucocytes and carbohydrate ligands expressed on lymph node high endothelial venules (HEV).1–5 Molecular identification of L-selectin ligands has been assisted through the use of a monoclonal antibody (mAb), MECA 79,6,7 that recognizes a sulphated carbohydrate epitope present on most L-selectin ligands and which inhibits the binding of lymphocytes to peripheral lymph node HEV.6,8–11 The first two L-selectin ligands identified from lymphoid tissues, glycosylation cell adhesion molecule (GlyCAM-1; a secreted ligand) and CD34 (a cell-surface ligand), both bound MECA 79.11–14 Two further ligands expressed by human tonsillar- and Peyer's patch-HEV, podocalyxin-like protein (PCLP) and mucosal-associated cell adhesion molecule (MadCAM), respectively, were also MECA 79 reactive.15,16

Recent investigations have identified L-selectin ligands that are not recognized by MECA 79, but which can still initiate tethering and rolling of lymphocytes on peripheral lymph node HEV.17 These remain to be fully characterized, but are known to include endothelial carbohydrate ligands bearing the sulphated sialyl-Lewisx determinant, recognized by mAbs CSLEX-1 and HECA-452.18 P-selectin glycoprotein-1 (PSGL-1) is another sulphated glycoprotein ligand expressed on leucocytes that shows no reactivity with MECA 79 but plays an important role in ‘secondary rolling’ (leucocyte-on-leucocyte interactions).19,20 These findings support the use of both mAb MECA 79 and an L-selectin fusion protein for the further definition of L-selectin ligands.

Selectin–ZZ fusion proteins have been used with success in a number of ligand-binding studies.21–23 These fusion proteins are designed to counteract the fast dissociation rates (≥ 10/second)24 of L-selectin–ligand interactions by presenting the fusion protein to its ligand in multivalent form, thereby increasing the avidity of the interaction. In the present study, L-selectin–ZZ was used to identify a novel MECA 79-negative L-selectin ligand in porcine inguinal lymph nodes. Characterization of this ligand has shown it to be a MECA 79 non-reactive chondroitin sulphate glycosaminoglycan-modified glycoprotein of high molecular weight (MW) (> 220 000).

Materials and methods

L-selectin–ZZ and reagents

Recombinant human L- and E-selectins lacking the transmembrane and cytosolic domains were produced by Bernard Allet (Glaxo Institute of Molecular Biology, Geneva, Switzerland) as C-terminal chimeras with the ‘ZZ’ domain of protein A. The fusion proteins were expressed using a baculovirus/insect cell system and affinity purified on immunoglobulin G (IgG), as previously described.25,26 Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Dako-Immunoglobulin (Glostrup, Denmark). EGTA, mannose-6-phosphate, trypsin (EC 3.4.21.4), soya bean trypsin inhibitor, heparinase I (EC 4.2.2.7), heparinase III (4.2.2.8) and chondroitin ABC lyase (EC 4.2.2.4) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Dorset, UK). Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase (EC 3.4.24.57) was purchased from Cedarlane Laboratories (Hornby, Ontario, Canada) and Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase was from Oxford GlycoSystems (Abingdon, UK).

Fractionation of lymph node-conditioned medium by anion-exchange chromatography

Inguinal lymph nodes from outbred farm pigs (Institute of Animal Health, Compton, UK) were cut into 1-mm-thick slices using a razor blade, washed three times with Hanks' balanced salt solution (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) and resuspended at a ratio of 1 g/ml in RPMI-1640, containing 25 mm HEPES, 50 U/ml penicillin G, 50 mg/ml streptomycin and 2 mm l-glutamine. Conditioned medium was harvested after 18 hr of incubation at 37°, centrifuged at 1100 g for 10 min to remove cellular debris and further precleared by centrifugation at 18 000 g for 2 min. After passing through a 0·2-µm filter, 2-ml aliquots were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and, when required, thawed overnight at 4°. For anion-exchange chromatography, 10 ml of filtered supernatant was diluted 1 : 5 with buffer A (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7·5, 0·02% sodium azide), in order to lower the salt concentration to < 30 mm, prior to loading over a 1-ml RESOURCE Q™ anion-exchange column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Amersham, UK). Fifty millilitres of diluted supernatant was loaded onto the anion-exchange column, using a super loop, at a rate of 2 ml/min, washed with two column volumes (CV) of buffer A and then eluted using buffer B (1 m sodium chloride in 10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, 0·02% sodium azide) over a 20-CV gradient. The eluate fraction size was 1 ml.

L-selectin–ZZ solid-phase binding assay

Anion-exchange fractions were diluted 1 : 5 in 100 mm sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 9·6) and used to coat triplicate wells of a 96-well plate (100 µl/well) (Maxisorp; Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The remainder of the assay was as described previously by Malhotra et al.21 Briefly, after overnight incubation at 4°, plates were washed three times with 10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·4, containing 2 mm calcium chloride and 0·1% Tween-20. Wells were then blocked with 200 µl of Tris buffer containing 0·1% Tween and left sealed for 2 hr at room temperature. Plates were washed, as described above, following which triplicate wells were incubated with 100 µl of L-selectin–ZZ and a 1 : 250 dilution of HRP-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG in the presence or absence of competitive inhibitors or enzymes and then incubated for 1 hr at ambient temperature. Because of the risk of losing the L-selectin–ligand complex as a result of its high dissociation rate, L-selectin–ZZ and the HRP conjugate were combined in the same step to minimize the number of washes. After gently washing once and tapping dry, 100 µl of fresh SIGMA FAST™ OPD (o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride) substrate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added and the colour reaction stopped using 3 m sulphuric acid prior to calorimetric determination at 490 nm. The fractions that displayed the greatest binding were combined into fractions A–D, dialysed against 10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, and then reassayed for L-selectin binding. EGTA, mannose-6-phosphate and anti-L-selectin mAb DREG-56 (Coulter Immunology, Hialeah, FL) were added at the L-selectin–ZZ step at the concentrations indicated.

Affinity purification of anion-exchange fractionated ligands

Pooled anion-exchange fraction D was precleared overnight by mixing with protein A–agarose beads (ACL, Isle of Man, UK), at a ratio of 1 : 5, at 4°. Concomitantly, 500 µg of L-selectin–ZZ was incubated with 500 µl of IgG–agarose beads overnight on rollers at 4°. The precleared sample was then added to L-selectin–ZZ-IgG–agarose, mixing as described above, for 6 hr at 4°, and L-selectin ligand(s) were eluted overnight in the presence of 10 mm EDTA in 10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, at 4°.

Biochemical characterization of putative L-selectin ligands

Enzymatic digestion of the L-selectin ligand in fraction D was carried out in triplicate wells of plates coated and blocked as described above. After the blocking step, 100 µl of enzyme was added to each well at the following concentrations and incubation periods at 37°: heparinase-I (5 U/ml) and -III (2·5 U/ml) for 3 hr; trypsin TCPK (100 µg/ml) for 3 hr, followed by inactivation with soya bean trypsin inhibitor (200 µg/ml) for a further 3 hr; OSGP (0·2 mg/ml), A. ureafaciens sialidase (0·1 U/ml) and chondroitin ABC lyase (0·1 U/ml) for 18 hr. Enzyme activity was confirmed at the concentration indicated in appropriate control experiments carried out in Tris, pH 7·4, assay buffer. After enzymatic treatment, wells were washed three times in Tris buffer containing 0·1% Tween and L-selectin–ZZ plus HRP-conjugated swine anti-rabbit IgG, added as described above.

MECA 79 Western blotting and Glycotrack staining of sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gels

Samples containing putative L-selectin ligands were applied under non-reducing conditions to 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels (20 µl per lane) and electrophoresed at 180 V for 1·5 hr. Molecular-weight markers were purchased from Bio-Rad (Herts, UK). For protein detection, gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R (Sigma-Aldrich). For Western blotting, proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Herts, UK) by ‘wet-blot’ transfer using a Bio-Rad™ apparatus and transfer buffer consisting of 25 mm Tris, pH 8·3, 192 mm glycine and 20% vol/vol methanol, for 18 hr at 30 V. The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% skimmed milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hr at room temperature with gentle shaking. The membrane was then washed three times, 5 min/wash, in PBS containing 0·1% Tween-20 (PBS/Tween). mAb MECA 79 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) hybridoma supernatant was added at a dilution of 1 : 5 in PBS/Tween containing 2% skimmed milk and incubated with the membrane for 1 hr at room temperature with rocking, as described above. The membrane was washed as described above and incubated for 1 hr with a 1 : 5000 dilution of donkey anti-rat HRP (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS/Tween containing 2% skimmed milk, as described previously. After washing the membrane, proteins were visualized using Enhanced Chemiluminescence™ (ECL) reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), prepared and used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The membrane was developed on Kodak XAR 5 film (Kodak, Herts, UK). For carbohydrate analysis, fraction D was incubated overnight at 4° with L-selectin–ZZ, eluted with EDTA, concentrated ×150 using a centricon concentrator and subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on a 7·5% gel under non-reducing conditions. To visualize highly glycosylated proteins, nitrocellulose membranes were stained with GlycoTrack™ (Oxford GlycoSystems), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Results

L-selectin binding activity of anion exchange-fractionated lymph node-conditioned medium

Conditioned medium was collected from porcine inguinal lymph nodes after 18 hr of incubation and fractionated through an anion-exchange column. Fractions 37–58, which were eluted in the salt gradient, plus fraction 32, a representative flow-through sample, were analysed for L-selectin binding activity using a solid-phase L-selectin–ZZ binding assay (Fig. 1a). Fractions 55, 56 and 57 displayed the greatest binding, followed by fractions 52, 53, 54, and 49, 50, 51. Pooled fractions B (55, 56, 57), C (52, 53, 54) and D (49, 50, 51) were dialysed against 10 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7·5, and pretreated with protein A–agarose to remove potential immunoglobulin contaminants, and then retested in the solid-phase L-selectin–ZZ binding assay (Fig. 1b). Fraction D exhibited the highest L-selectin binding, followed by B, C and the non-binding fraction A. Fractions D, B and C exhibited marked enrichment of L-selectin binding compared to unfractionated conditioned medium (CM).

Figure 1.

L-selectin binding and MECA 79 reactivity of anion-exchange fractionated lymph node-conditioned medium. (a) Binding of anion-exchange fractions to L-selectin–ZZ in a solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Microtitre wells were coated with 100 µl of fraction (diluted 1 : 5 to lower the salt content) and binding was determined by the addition of L-selectin–ZZ and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG), followed by calorimetric determination at 490 nm. (b) Pooled fractions were precleared using protein A to remove IgG contaminants and dialysed into Tris assay buffer, before reanalysis by solid-phase ELISA. (c) Western blot analysis of pooled fractions A to D with monoclonal antibody (mAb) MECA 79. Pooled fractions (20 µl) were separated under non-reducing conditions on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for detection using MECA 79. Fraction D, which exhibited the greatest binding capacity for L-selectin–ZZ, showed no detectable staining with MECA 79, whereas fraction B, with the second highest L-selectin binding capacity, contained two MECA 79-reactive species migrating at 84 kDa and 210 kDa, respectively. Bar charts depict the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate determinations.

Western blotting of anion-exchange fractions by mAb MECA 79

To determine whether MECA 79-reactive species were present in pooled fractions B–D, these fractions were Western blotted with mAb MECA 79 (Fig. 1c). Fraction D, which exhibited the highest L-selectin-binding activity, demonstrated no reactivity with mAb MECA 79, whereas fraction B showed MECA 79-reactive bands at 84 kDa and >210 kDa. Fractions C and A did not show any MECA 79 reactivity. Western blotting with a rat isotype control mAb (IgM κ) verified the specificity of the blotting procedure (data not shown).

Specificity of L-selectin binding by the MECA 79-negative ligand

The L-selectin ligand in fraction D, which did not exhibit any reactivity with MECA 79, was subjected to further analysis. After affinity purification over an L-selectin–ZZ-IgG–agarose column, the putative L-selectin ligand(s) were eluted using 10 mm EDTA, and specificity for L-selectin binding was determined in the solid-phase binding assay. Binding to L-selectin–ZZ was divalent-cation dependent, being abrogated in the presence of 10 mm EDTA (Fig. 2a). Mannose-6-phosphate dose-dependently inhibited the interaction (Fig. 2b), as did the anti-L-selectin antibody DREG 56 (Fig. 2c). These results therefore verified that affinity-purified material from anion-exchange fraction D contained L-selectin–ZZ reactivity that was Ca2+, lectin and L-selectin dependent, consistent with the presence of bona fide ligand(s) for L-selectin.

Figure 2.

Specificity of L-selectin binding by MECA 79-negative ligand(s) in fraction D. Panel (a) depicts specific binding by fraction D to L-selectin–ZZ, but not to E-selectin–ZZ, in the presence and absence of 10 mm EDTA. Panels (b) and (c) depict the dose-dependent inhibition of L-selectin–ZZ binding in the presence of increasing concentrations of mannose-6-phosphate and anti-L-selectin monoclonal antibody (mAb) DREG 56, respectively. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Biochemical characterization of the putative L-selectin ligand by enzymatic digestion

To determine the nature of the sugars and linkages present in the L-selectin reactive species present in fraction D, different enzymatic digests were carried out. Treatment of the ligand with heparinase I and -III did not lead to a decrease in L-selectin reactivity, suggesting that the ligand was not a heparan sulphate-modified proteoglycan (Fig. 3a). The activity of the heparinases was verified beforehand by removal of the pan-heparan sulphate epitope, 10E4, and concomitant appearance of the heparinase-sensitive ‘stub’ epitope, 3G10 (data not shown). In contrast, treatment with trypsin and A. ureafaciens sialidase reduced the reactivity of the ligand by 30% and 17%, respectively (Fig. 3b, 3c). Treatment with OSGP, which specifically cleaves O-linked sialomucins, resulted in a 23% decrease in binding to L-selectin (Fig. 3d). When the immobilized L-selectin ligand was incubated with chondroitin ABC lyase, a dose-dependent reduction of L-selectin binding was observed, reaching 82% at ≥ 0·1 U/ml (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results suggest that the moieties which mediated L-selectin binding were predominantly chondroitin sulphate glycosaminoglycan-modifed, containing some relevant O-linked sialomucin determinants.

Figure 3.

Biochemical characterization of the L-selectin ligand(s) in fraction D. Microtitre wells were coated with ligand from fraction D, and binding to L-selectin–ZZ was assessed in the presence and absence of enzymatic treatment, as follows. (a) Heparinases I and III exerted no effect on L-selectin binding, ruling out the involvement of heparan sulphate determinants. (b) Trypsin followed by reversal with soya-bean trypsin inhibitor (T, I) reduced L-selectin binding by 30% compared to untreated, inhibitor only (I), or simultaneous treatment with trypsin in the presence of inhibitor (T + I). (c) Arthrobacter ureafaciens sialidase treatment reduced L-selectin binding by 17%. (d) O-sialoglycoprotease endopeptidase (OSGP) treatment inhibited L-selectin reactivity by 23%. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

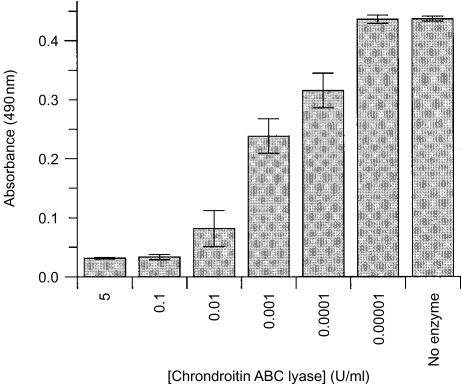

Figure 4.

Inhibition of L-selectin binding by chondroitin ABC lyase. Fraction D was immobilized to microtitre wells (as described in the Materials and methods) and treated with chondroitin ABC lyase, at the concentrations indicated, for 18 hr at 37°. Chondroitin ABC lyase treatment caused a dose-dependent inhibition of L-selectin–ZZ binding, achieving maximal inhibition (82%) at ≥ 0·1 U/ml. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (SD) (n = 3).

Carbohydrate staining of the L-selectin ligand by GlycoTrack

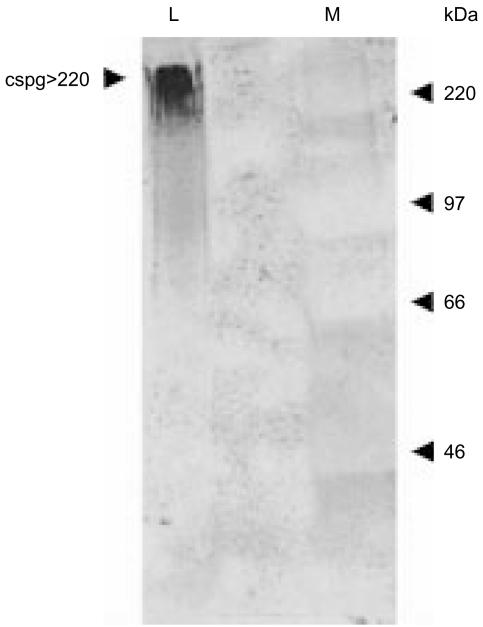

As Coomassie Blue staining failed to detect an L-selectin reactive protein in fraction D (data not shown), and because a number of previous reports have shown L-selectin ligands to be highly glycosylated, the putative L-selectin ligand was subjected to staining by GlycoTrack. This staining method detects glycoproteins by biotinylating the hydroxyl groups in the monosaccharide ring structure, which can then be visualized using a streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase conjugate, followed by colour development. This permits visualization of highly glycosylated glycoproteins that might otherwise remain undetected by conventional protein-staining techniques. For these experiments, fraction D was incubated with L-selectin–ZZ agarose beads and the eluate subjected to SDS–PAGE under non-reducing conditions followed by transfer to nitrocellulose. Staining with Glycotrack revealed a single high-molecular-weight band which migrated at > 220 kDa (Fig. 5). The size and intense reactivity with GlycoTrack was consistent with the L-selectin reactivity being caused by a chondroitin sulphate proteoglycan, which we have therefore designated csgp > 220.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the L-selectin ligand by Glycotrack™. Fraction D was incubated overnight with L-selectin–ZZ agarose beads, after which bound material was eluted with 10 mm EDTA. The eluate was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) under non-reducing conditions and transferred to nitrocellulose. Glycosylated oligosaccharide residues were identified using the Glycotrack carbohydrate detection kit (Oxford GlycoSystems, Abingdon, UK), which revealed a single high molecular weight species migrating at > 220 kDa.

Discussion

The identification of csgp>220, a MECA 79-negative L-selectin ligand secreted by porcine lymphoid tissue, was made possible using an L-selectin–ZZ fusion protein as a primary screening agent and MECA 79 as a secondary Western blotting agent. Previous researchers have sometimes prejudiced their screening programmes for L-selectin ligands by ‘enriching’ tissue material by passage through MECA 79-affinity columns, before presenting it to L-selectin fusion proteins.15 This method may inadvertently result in the loss of bona fide L-selectin ligands that lack the necessary MECA 79 epitopes. Thus, it is possible that homologues of csgp > 220 are also present in mouse and human tissue but remain, as yet, undetected.

Two MECA 79-reactive proteins were identified in pooled fraction B of the anion-exchange column, which migrated at apparent molecular weights (MW) of 84 000 and 210 000. The 84 000-MW moiety may have represented a more extensively glycosylated porcine homologueue of GlyCAM-1. Murine GlyCAM-1 has a predicted MW of 14 000, but as its actual total MW is ≈ 50 000, this suggests that extensive O-linked glycans make-up the majority of its apparent MW.12 An alternative theoretical possibility is that the 84 000-MW band represented a soluble form of MAdCAM-1. This possibility is supported by immunoprecipitation from murine peripheral lymph node lysates using MECA 79-coupled agarose beads of a 65 000-MW band, which was identified as MAdCAM-1. MAdCAM-1 has been detected in the peripheral and mesenteric lymph nodes of young mice and in Peyer's patches of adult mice.11 The 210 000-MW species is unlikely to be CD34, as the porcine homologue of CD34 has been identified in inguinal lymph node lysates and migrates at ≈ 140 000 MW.27 The 210 000-MW species may, however, represent a soluble porcine homologue of murine sgp200 (sulphated glycoprotein 200 kDa), which has been identified in murine peripheral lymph node lysates.11 It was also noted that anion-exchange fractions B and C exhibited residual reactivity with an E-selectin–ZZ chimera. This was probably a result of the presence of immunoglobulin, secreted by resident lymph node B cells, which binds to the protein A (Fc-binding) domain of the ZZ-tail. An alternative theoretical possibility is that reactivity was caused by PSGL-1, which might also bind E-selectin.28 This possibility is considered remote, however, as PSGL-1 is an integral membrane protein. In light of the above considerations, further analysis in this study was confined to fraction D, which displayed the highest reactivity with L-selectin–ZZ, but no reactivity with MECA 79 or E-selectin–ZZ.

The binding of L-selectin–ZZ to csgp>220 was calcium dependent and dose-dependently inhibited by mannose-6-phosphate and DREG 56, all characteristic of a bona fide L-selectin ligand. Furthermore, affinity-purified fraction D exhibited no reactivity to E-selectin–ZZ, therefore ruling out the possibility of non-specific immunoglobulin reactivity. The use of a human L-selectin chimera to study porcine L-selectin ligands was justified by the known cross-species reactivity of L-selectin29 and the fact that human L-selectin-Fc has been previously used to isolate porcine CD34 from lymph node lysates.27 The insensitivity of csgp>220 to heparinase I and -III ruled out the involvement of a heparan sulphate proteoglycan moiety in the L-selectin interaction. The A. ureafaciens sialidase, OSGP, and trypsin demonstrated some reduction in binding to L-selectin–ZZ, but the greatest effect was achieved using chondroitin ABC lyase. Thus, binding of L-selectin to csgp>220 appeared to be mediated predominantly via chondroitin sulphate-modified glycosaminoglycan with some contribution through O-linked sialomucin determinants.

Previous L-selectin ligands have been classified as sialomucins,5,11–16,27 heparan sulphate proteoglycans,30–33 or chondroitin sulphate-modified proteoglycans.34,35 Two rat L-selectin ligands have been identified in the conditioned medium of high endothelial cell (HEC) cultures and lymph node organ cultures, using anion-exchange chromatography.34 As they co-eluted in the same fraction, they were designated by the nomenclature Sgp150/>200 and biochemical analysis revealed them to be chondroitin sulphate-modified proteoglycans. Derry et al.34 further demonstrated that trypsin and chondroitin ABC lyase reduced binding of Sgp150/>200 to L-selectin–Fc by 66% and 54%, respectively. csgp>220 exhibited different sensitivity to these enzymes (30% and 82%, respectively), which may indicate either a higher content of chondroitin sulphate linkages in csgp>220 relative to Sgp150/>220, or slight differences in the reaction conditions used between the two studies. Because chondroitin ABC lyase does not discriminate between chondroitin-4-sulphate (A), dermatan sulphate (B) or chondroitin-6-sulphate (C), it is not yet clear if some, or all, of these motifs participate in the binding of csgp>220 with L-selectin. In the case of Sgp150/>200 it is known that dermatan sulphate is not involved in the binding to L-selectin.34 However, a significant additional property that can be ascribed to the porcine ligand described in the present work, is that csgp>220 is MECA 79 non-reactive (this could not be established for the rat ligand Sgp150/>200, as MECA 79 is a rat antibody).

It remains to be seen whether csgp>220 is a porcine homologue of Sgp150/>200, but the identification of csgp>220 adds to the emerging class of L-selectin ligands in which binding is primarily mediated through chondroitin sulphate-modified determinants.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr Richard Priest, and Ms Sara Witham for their assistance in preparing the L-selectin–ZZ construct; Drs Tim Hickling, Martin Everett and Ms Valerie Kelly for FPLC help; and Drs Mike Bird, Sussan Nourshargh and Justin Mason for many useful discussions. This work was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

References

- 1.Gallatin WM, Weissman IL, Butcher EC. A cell-surface molecule involved in organ-specific homing of lymphocytes. Nature. 1983;304:30–4. doi: 10.1038/304030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasky LA, Singer MS, Yednock TA, et al. Cloning of a lymphocyte homing receptor reveals a lectin domain. Cell. 1989;56:1045–55. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stoolman LM, Rosen SD. Possible role for cell-surface carbohydrate-binding molecules in lymphocyte recirculation. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:722–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.3.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoolman LM, Tenforde TS, Rosen SD. Phosphomannosyl receptors may participate in the adhesive interaction between lymphocytes and high endothelial venules. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:1535–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.4.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imai Y, Singer MS, Fennie C, Lasky LA, Rosen SD. Identification of a carbohydrate-based endothelial ligand for a lymphocyte homing receptor. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:1213–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.5.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Streeter PR, Rouse BT, Butcher EC. Immunohistologic and functional characterization of a vascular addressin involved in lymphocyte homing into peripheral lymph nodes. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1853–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streeter PR, Berg EL, Rouse BT, Bargatze RF, Butcher EC. A tissue-specific endothelial cell molecule involved in lymphocyte homing. Nature. 1988;331:41–6. doi: 10.1038/331041a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson SR, Imai Y, Fennie C, Geoffroy JS, Rosen SD, Lasky LA. A homing receptor-IgG chimera as a probe for adhesive ligands of lymph node high endothelial venules. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2221–9. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michie SA, Streeter PR, Bolt PA, Butcher EC, Picker LJ. The human peripheral lymph node vascular addressin. An inducible endothelial antigen involved in lymphocyte homing. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1688–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whyte A, Wooding P, Nayeem N, Watson SR, Rosen SD, Binns RM. The L-selectin counter-receptor in porcine lymph nodes. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:159S. doi: 10.1042/bst023159s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmerich S, Butcher EC, Rosen SD. Sulfation-dependent recognition of high endothelial venules (HEV)-ligands by L-selectin and MECA 79, an adhesion-blocking monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2219–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasky LA, Singer MS, Dowbenko D, et al. An endothelial ligand for L-selectin is a novel mucin-like molecule. Cell. 1992;69:927–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90612-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai Y, Lasky LA, Rosen SD. Sulphation requirement for GlyCAM-1, an endothelial ligand for L-selectin. Nature. 1993;361:555–7. doi: 10.1038/361555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumheter S, Singer MS, Henzel W, et al. Binding of L-selectin to the vascular sialomucin CD34. Science. 1993;262:436–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7692600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sassetti C, Tangemann K, Singer MS, Kershaw DB, Rosen SD. Identification of podocalyxin-like protein as a high endothelial venule ligand for L-selectin: parallels to CD34. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1965–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg EL, McEvoy LM, Berlin C, Bargatze RF, Butcher EC. L-selectin-mediated lymphocyte rolling on MAdCAM-1. Nature. 1993;366:695–8. doi: 10.1038/366695a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark RA, Fuhlbrigge RC, Springer TA. L-Selectin ligands that are O-glycoprotease resistant and distinct from MECA-79 antigen are sufficient for tethering and rolling of lymphocytes on human high endothelial venules. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:721–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu L, Delahunty MD, Ding H, Luscinskas FW, Tedder TF. The cutaneous lymphocyte antigen is an essential component of the L-selectin ligand induced on human vascular endothelial cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:241–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tu L, Murphy PG, Li X, Tedder TF. L-selectin ligands expressed by human leukocytes are HECA-452 antibody-defined carbohydrate epitopes preferentially displayed by P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. J Immunol. 1999;163:5070–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walcheck B, Moore KL, McEver RP, Kishimoto TK. Neutrophil–neutrophil interactions under hydrodynamic shear stress involve L-selectin and PSGL-1. A mechanism that amplifies initial leukocyte accumulation of P-selectin in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1081–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI118888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra R, Ward M, Sim RB, Bird MI. Identification of human complement Factor H as a ligand for L-selectin. Biochem J. 1999;341:61–9. 10.1042/0264-6021:3410061. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malhotra R, Taylor NR, Bird MI. Anionic phospholipids bind to L-selectin (but not E-selectin) at a site distinct from the carbohydrate-binding site. Biochem J. 1996;314:297–303. doi: 10.1042/bj3140297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Priest R, Bird MI, Malhotra R. Characterization of E-selectin-binding epitopes expressed by skin-homing T cells. Immunology. 1998;94:523–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00551.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholson MW, Barclay AN, Singer MS, Rosen SD, van der Merwe PA. Affinity and kinetic analysis of L-selectin (CD62L) binding to glycosylation-dependent cell-adhesion molecule-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:763–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.2.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Priest R, Nawaz S, Green PM, Bird MI. Adhesion of eosinophils to E- & P-selectin. Biochem Soc Trans. 1995;23:162S. doi: 10.1042/bst023162s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhotra R, Priest R, Bird MI. Role for L-selectin in lipopolysaccharide-induced activation of neutrophils. Biochem J. 1996;320:589–93. doi: 10.1042/bj3200589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shailubhai K, Streeter PR, Smith CE, Jacob GS. Sulfation and sialylation requirements for a glycoform of CD34, a major endothelial ligand for L-selectin in porcine peripheral lymph nodes. Glycobiology. 1997;7:305–14. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goetz DJ, Greif DM, Ding H, et al. Isolated P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 dynamic adhesion to P- and E-selectin. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:509–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoolman LM, Yednock TA, Rosen SD. Homing receptors on human and rodent lymphocytes – evidence for a conserved carbohydrate-binding specificity. Blood. 1987;70:1842–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norgard-Sumnicht KE, Varki NM, Varki A. Calcium-dependent heparin-like ligands for L-selectin in nonlymphoid endothelial cells. Science. 1993;261:480–3. doi: 10.1126/science.7687382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giuffre L, Cordey AS, Monai N, Tardy Y, Schapira M, Spertini O. Monocyte adhesion to activated aortic endothelium: role of L-selectin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:945–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.4.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YF, Kawashima H, Watanabe N, Miyasaka M. Identification and characterization of ligands for L-selectin in the kidney. II. Expression of chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate proteoglycans reactive with 1-selectin. FEBS Lett. 1999;444:201–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watanabe N, Kawashima H, Li YF, Miyasaka M. Identification and characterization of ligands for L-selectin in the kidney. III. Characterization of L-selectin reactive heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1999;125:826–31. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derry CJ, Faveeuw C, Mordsley KR, Ager A. Novel chondroitin sulfate-modified ligands for L-selectin on lymph node high endothelial venules. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:419–30. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199902)29:02<419::AID-IMMU419>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawashima H, Li YF, Watanabe N, Hirose J, Hirose M, Miyasaka M. Identification and characterization of ligands for L-selectin in the kidney. I. Versican, a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, is a ligand for L-selectin. Int Immunol. 1999;11:393–405. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]