Abstract

Recovery of total T cell numbers after in vivo T-cell depletion in humans is accompanied by complex perturbation within the CD8+ subset. We aimed to elucidate the reconstitution of CD8+ T cells by separate analysis of putative naïve CD95− CD28+, memory CD95+ CD28+ and CD28− T cell compartments after acute maximal depletion by high-dose chemotherapy (HD-ChT) in women with high-risk breast cancer. We found that recovery of putative naïve CD8+ CD95− CD28+ and CD4+ CD95− CD28+ T cells, was compatible with a thymus-dependent regenerative pathway since their recovery was slow and time-dependent, their values were tightly related to each other, and their reconstitution patterns were inversely related to age. By analysing non-naïve T cells, a striking diversion between putative memory T cells and CD28− T cells was found. These latter increased early well beyond normal values, thus playing a pivotal role in total T-cell homeostasis, and contributed to reduce the CD4 : CD8 ratio. In contrast, putative memory T cells returned to values not significantly different from those seen in patients at diagnosis, indicating that this compartment may recover after HD-ChT. At 3–5 years after treatment, naïve T cells persisted at low levels, with expansion of CD28− T cells, suggesting that such alterations may extend further. These findings indicate that CD28− T cells were responsible for ‘blind’ T-cell homeostasis, but support the notion that memory and naïve T cells are regulated separately. Given their distinct dynamics, quantitative evaluation of T-cell pools in patients undergoing chemotherapy should take into account separate analysis of naïve, memory and CD28− T cells.

Introduction

Correct representation of the T-cell pool is essential to maintain adequate immune competence against pathogens, since it has to maintain a sufficiently diverse repertoire of naïve T cells to recognize a broad range of antigens, while efficient immune responses against previously encountered pathogens depend on the memory T-cell pool.1 For these demanding tasks, homeostatic mechanisms have evolved to maintain distinct populations of naïve and memory cells and to retain an appropriate mixture of CD4+ helper T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Studies on T-cell homeostasis in animals have revealed that naïve and memory T-cell pools are regulated separately within independent homeostatic niches.2 By contrast, in human peripheral blood the absolute number of T lymphocytes appears to be steadily regulated throughout adult life,3 while the CD4 : CD8 ratio seems to be under genetic control in physiological conditions.4,5 More recently, additional mechanisms involving peripheral expansion by antigen-driven immune responses6 and availability of cytokines such as interleukin-7 have also been shown, especially when thymic function is abolished.7 Thus, T-cell homeostasis appears to be regulated at different levels by mechanisms that are probably distinct, but that are as yet poorly understood.

Understanding the efficiency of homeostatic mechanisms may be critical in several settings characterized by T-cell depletion, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, cytotoxic chemotherapy and advanced aging. However, the interpretation of altered T-cell pool composition is still surrounded by many controversies and mainly oriented to evaluation of the CD4+ subset. In an attempt to gain insight into the altered T-cell pool composition after in vivo T-cell depletion, we chose to study patients with breast cancer treated with high-dose cytotoxic chemotherapy (HD-ChT) in the autologous setting, primarily because this method is free of puzzling effects deriving from graft-versus-host reaction and immunosuppressive drugs. Secondly, despite T cells being transferred within grafts8 and/or surviving cytotoxic therapy within the recipient, the T cells in the peripheral blood usually remain undetectable for at least 10 days and do not recover normal ranges until at least 3 months after treatment,9 indicating an acute and near to complete ablation of T lymphocytes.10 Lastly, most patients with solid malignancies are exempt from diseases primarily affecting the lymphoid organs and possibly interfering with immune reconstitution. Besides, HD-ChT has gained wide application in patients bearing solid malignancies in the last 10 years with the advent of peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC) mobilization by haematopoietic growth factors, which allows proper harvest by leukapheresis. Therefore, both short- and long-term alterations of the T-cell pool may have relevant clinical impact on the immune competence of patients treated with HD-ChT and autologous PBSC.

The versatility of primary immune responses by naïve cells and the efficiency of recall responses by memory cells are both essential for immune competence. In the CD4+ subset, the phenotypic definition of naïve and memory cells, based on the expression of CD45 isoforms, has allowed extensive evaluation of T-cell reconstitution after pharmacological T-cell depletion.11 But in contrast to the CD4+ subset, altered representation of CD8+ T cells still awaits organization. Reportedly, naïve CD4+ recovery is usually slow, but naïve CD8+ recovery is rapid (and seemingly not thymus-dependent), with complex CD8+ perturbation and inverted CD4 : CD8 ratio.12 More recently, in myeloma patients treated with HD-ChT and autologous PBSC, it has been shown that thymic output can still play a significant role in adults' T-cell reconstitution not only for CD4+, but also for CD8+ T cells.13 As a result, some aspects of T-cell reconstitution, especially regarding CD8+ subsets, still remain elusive.

We recently hypothesized that complex phenotypic perturbation of CD8+ T cells may be reconciled by expansion of CD28− T cells and that phenotypic distinction of naïve T cells should take into account the aberrant phenotype of CD28− T cells expressing CD45RA. Following this assumption, we have identified naïve T cells as CD95− CD28+ T lymphocytes for their phenotypic and functional features, and for their coincidence with CD45RA+ 62L+ T cells.14 In the study presented herein, we analysed separately CD95− CD28+ putative naïve, CD95+ CD28+ putative memory and CD28− T-cell compartments. By using this phenotypic approach we observed distinct dynamics of the three cell types that were consistent with distinct regulation of naïve and memory compartments, as well as with homeostasis of the whole T-cell number due to compensatory expansion by effector CD28− T cells. These findings provide an overall picture of T-cell homeostasis in humans after HD-ChT and suggest a new scheme for the interpretation of immunodeficiency deriving from chemotherapy.

Materials and methods

Study subjects and clinical protocols

The study population comprised a group of 120 patients with breast cancer referred to the Salvatore Maugeri Foundation at Pavia Scientific Institute, between 1995 and 2001. Of these, 20 patients were studied at diagnosis before any treatment, whereas a separate group consisting of 100 patients were studied at a single time-point between 15 days and 65 months after treatment with HD-ChT and autologous PBSC transplantation. A large majority of patients had primary high-risk breast cancer, defined as 10 or more involved axillary nodes or as four or more involved nodes in association with other detrimental prognostic factors, such as either large tumour size, or poor nuclear grading, or young age at diagnosis (less than 35 years). Primary breast cancer patients received a mobilizing regimen with cyclophosphamide (7 g/m2) plus filgrastim (5 µg/kg/day) starting 48 hr after chemotherapy and administered until a total of at least 5 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg body weight could be harvested by leukapheresis. The myeloablative regimen consisted of thiotepa (600 mg/m2) on day −3, and melphalan (160 mg/m2) on day −1. In a minority of patients (n = 15) with metastatic breast cancer responsive to induction chemotherapy, the mobilizing regimen consisted instead of epirubicin (90 mg/m2) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) plus filgrastim, as previously described,15 while myeloablation was induced by administration of mitoxantrone (60 mg/m2) on day −5, thiotepa (500 mg/m2) on days −4 to −2, and cyclophosphamide (6 g/m2) on days −4 to −2. The median age of all treated patients was 46 years and performance status was good (< 1 WHO) in the majority of patients. In both groups of patients, with primary high-risk or metastatic breast cancer, autologous PBSC were thawed and reinfused on day 0. A median of 6·75 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg was reinfused (range 2·5× 106−12 × 106 CD34+ cells/kg) and filgrastim was administrated at a daily dose of 5 µg/kg from day 0 until haematological recovery, defined as total white blood cells > 500/μl and platelets > 20 000/μl. After completion of therapy, evaluated patients were without evidence of disease when tested. In addition to breast cancer patients, 40 healthy age-matched women were selected as previously described,14 and evaluated to assess the relationship between CD8+ CD28− T-cell numbers and CD4 : CD8 ratios in normal donors.

Flow cytometry analysis

From each patient or healthy control, blood was drawn by venepuncture for flow cytometry analysis and for complete blood count. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were prepared from 10 ml of heparinized blood by Ficoll–Hypaque density centrifugation. After washings with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), cells were counted, resuspended in 90% FCS + 10% dimethylsulphoxide solution on ice at a cell concentration less than 10 × 106/ml and finally frozen in liquid nitrogen after intermediate cooling at −80° in a methanol-containing device. Absolute numbers for each cell subset reported here were calculated by multiplying their representation among lymphocytes by the absolute lymphocyte count, determined by complete blood count before freezing by a Coulter cell counter (Hialeah, FL). For testing, freshly thawed PBMC were washed in FCS-containing medium, finally resuspended in PBS containing 1% FCS, 1% human serum, 10% mouse serum and 0·01% sodium azide, then stained for 30 min on ice with saturating amounts of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) conjugated with three fluorochromes: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE) and CyChrome™. After staining, cells were washed and analysed by flow cytometry with FACScan or FACScalibur flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, BDIS, San Josè, CA) each equipped with a 488-nm argon laser and operated with Lysis II or with CellQest softwares, respectively. Instrument compensation was adjusted first by acquisition of cell samples individually stained with each fluorochrome-conjugated mAb and then further by running cell samples obtained by mixing two by two and finally three by three different single-stain, bright-positive controls. After thawing, the viability of lymphocytes was consistently higher than 85%, as evaluated with flow cytometry by standard propidium iodide incorporation. For each sample, characteristic forward angle and side scatter profiles of lymphocytes that did not incorporate propidium iodide were used to set an acquisition gate of 104 cells, whereas analysis was carried out later on side scatter low and CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells. In preliminary experiments conducted in parallel on fresh whole red cell lysed peripheral blood (taken from the same donors) by the standard cytofluorimetric method, as described elsewhere,16 and on thawed PBMC, as described above, we found that frequencies of CD3+ cells among lymphocytes and of each CD3+ subset further reported here, were not significantly different (data not shown).

The following fluorochrome-conjugated mAbs were obtained from PharMingen (BDIS, San Diego, CA): FITC-conjugated anti-CD4 [clone RPA-T4, mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1), l], anti-CD45RA (HI100, mouse IgG2b, k), anti-CD95 (DX2, mouse IgG1, k); PE-conjugated anti-CD8 (HIT8a, mouse IgG1, k), anti-CD28 (CD28.2, mouse IgG1, k), anti-CD62L (DREG-56, mouse IgG1, k); CyChrome™-conjugated: anti-CD3 (UCHT1, mouse IgG1, k), anti-CD4 (RPA-T4, mouse IgG1, l), anti-CD8 (HIT8a, mouse IgG1, k). For setting quadrants and gate limits of non-specific immunoglobulin cell-binding (negative controls), we used IgG1 of irrelevant specificity, conjugated to FITC-, PE-, or CyChrome™, obtained from the same manufacturer.

To obtain percentages as well as absolute numbers of CD3+, CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ cells among lymphocytes, PBMC were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD4, PE-conjugated anti-CD8 and CyChrome™-conjugated anti-CD3. Thereafter, during analysis an electronic gate placed on CD3+ cells and correlated expression of CD4 or CD8, allowed us to calculate percentages and absolute numbers of CD3+, CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ lymphocytes. For other subsets frequencies, PBMC were stained with either CyChrome™-conjugated anti-CD3, anti-CD4, or anti-CD8 along with both anti-CD28-PE and anti-CD95-FITC mAbs. To analyse CD4+ and CD8+ single subsets, we used a cell gate uniquely identifying side-scatterlow CD4+hi cells (to exclude myeloid mononuclear cells) or CD8hi cells (to exclude CD3− CD8+ natural killer cells). Absolute number of individual CD3, CD4, or CD8 T cells expressing a particular phenotype, were calculated by multiplying their percentages from flow cytometry gating by the absolute count/μl of each population.

Statistical analysis

Comparison between groups was done by two-tailed non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. Relationships between absolute numbers of cell subsets with each other or with other parameters, including time elapsed from HD-ChT and patients' age, were tested by both linear regression analysis and Spearman's correlation coefficient. Relationships between CD8+ CD28− T cells and CD4 : CD8 ratios were tested by logarithmic regression analysis. In all cases, a P-value lower than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of non-naïve CD28+, naïve and CD28− T cells in healthy donors and patients with breast cancer

Measurement of naïve T cells using phenotypic markers is still controversial. De Rosa et al. have recently shown by a sophisticated 11-colour, 13-parameter flow cytometry methodology (so-called polychromatic flow cytometry) that the use of two appropriate markers, including the standard definition of a CD45RA+ CD62L+ population, allows identification of 97–98% of naïve CD4+ cells and 87–93% of naïve CD8+ cells.17 Thus, such restriction inevitably applies also to the study presented here, for the purposes of which we have chosen the CD95 versus CD28 cell surface staining combination (Fig. 1, top plots). Indeed, as previously demonstrated elsewhere in normal subjects,14 we found also in breast cancer patients that the large majority of CD95− cells were CD62L+ and CD45RA+ (Fig. 1, middle plots), and that frequencies of CD95− CD28+ cells (Fig. 1, top plots) were almost overlapping to those given by CD45RA+ CD62L+ cells (Fig. 1, bottom plots). It should also be noted that, in contrast to CD45RA, the CD95 antigen has the same expression intensity on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and its combination with CD28 may offer a cleaner resolution than CD45RA versus CD62L.

Figure 1.

Three-colour flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to discriminate putative naïve T cells in a breast cancer patient 12 months after treatment with HD-ChT. PBMC were stained with combinations of mAbs against either CD4 or CD8 (conjugated to CyChrome™) plus FITC- and PE-conjugated mAbs as indicated and an electronic gate was set on CD4+ (left column) or bright CD8+ (right column) lymphocytes. Probability 10% contour plots are shown. From top to the bottom, putative naïve T cells can be identified alternatively as CD95− CD28+, CD95− CD62L+, CD95− CD45RA+ and CD45RA+ CD62L+.

The choice of CD95 versus CD28 staining was based on the relevant objective to distinguish not only naïve from non-naïve T cells, but also to separate effector from memory cells within non-naïve T cells. In fact, the evaluation of CD28 surface differentiation antigen allows the separation of the extensively studied yet aberrant CD28− T cells subpopulation. CD28− T cells are well known at the phenotypic level for their expression of CD57, CD11b and CD45RA;18 at the functional level, they are known as cytotoxic effector cells;19 at the molecular level as an oligoclonal population with restricted repertoire.20 Thus, as shown in the top contour plots of Fig. 2, in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we could distinguish three subpopulations represented by CD95− CD28+ putative naïve T cells, by above mentioned CD28− T cells (with dim expression of CD95), and by the remaining CD95+ CD28+ putative memory T cells. When we tested patients at various intervals from HD-ChT, we found that the representation of these three subpopulations was modified. As shown in Fig. 2, the most remarkable and immediate alteration induced by HD-ChT was the disappearance of naïve T cells not only in the CD4+ but also in the CD8+ T-cell subset.

Figure 2.

Three-colour flow cytometry analysis of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients with breast cancer at diagnosis and after treatment with HD-ChT to discriminate putative naïve, memory and CD28− T cells. PBMC were stained with combinations of mAbs against either CD4 or CD8 (conjugated to CyChrome™) plus CD95-FITC and CD28-PE. Representative 10% probability contour plots are shown. An electronic gate was set on CD4+ (left column) or bright CD8+ (right column) lymphocytes, and expression of CD95-FITC (x axis) was correlated to CD28-PE (y axis). Gated cells were divided into three subsets including putative naïve CD95− CD28+ T cells (upper left cells, as identified on top of Figure 1), CD28− (lower cells), and putative memory CD95+ CD28+ (upper right cells).

Kinetics of T-cell recovery for naïve, memory and CD28− compartments

We tested, at various time-points, a broad cohort of patients with breast cancer who underwent HD-ChT in our institution. As far as CD95− CD28+ putative naïve T cells are concerned, we observed different recovery kinetics according to the ages of the patients tested (Fig. 3). In patients older than 55, there was almost no increase of such cells after HD-ChT. By contrast, in younger patients, the increase was directly related to time elapsed from HD-ChT within both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Interestingly, the correlation to time from HD-ChT and the slopes were significantly higher for patients under 40 years of age (slopes: +15·2/month with 95% confidence interval 9·6–20·7 for CD4+ T cells; +7·1/month with 95% confidence interval 5·6–8·7 for CD8+ T cells), as compared to patients 50–55 years (+ 6·3/month with 95% confidence interval 4·3–8·4 for CD4+ T cells; +3·0/month with 95% confidence interval 1·9–4·2 for CD8+ T cells). Therefore, in contrast to data previously reported in a similar clinical setting,21 we found a significant inverse relationship of putative naïve T cells with age after intense chemotherapy in both CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. Moreover, we found a tight correlation between values of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4), with a constant CD4 : CD8 ratio (not shown). Such a high correlation between CD4+ and CD8+ naïve T cells suggests a common origin and it seems unlikely that they could have derived from extra-thymic lymphopoiesis by gut, liver, or bone marrow, since T cells from these latter origins are predominantly CD8+ or CD4− CD8− (double-negative) cells.

Figure 3.

Recovery of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ naïve T cells after HD-ChT. Data obtained from 80 patients evaluated within 3 years from HD-ChT, were plotted versus time (months) elapsed from HD-ChT as individual data points. Patients were divided into three groups according to age, as indicated. R2 values were calculated by linear regression analysis.

Figure 4.

Relationship between naïve CD4+ and naïve CD8+ T-cell numbers during recovery from HD-ChT. naïve CD4+ versus CD8+ T cells from 80 patients evaluated within 3 years of HD-ChT, were plotted as individual data points. R2 values were calculated by linear regression analysis.

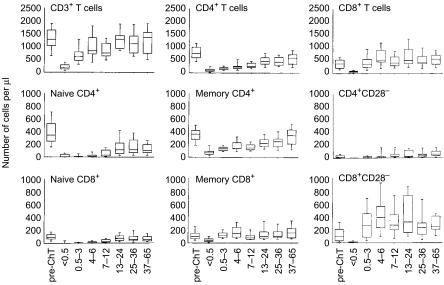

When we analysed recovery of CD28− and CD95+ CD28+ T cells, we could not find a significant relationship, neither with time from treatment nor with patients' age (not shown). The kinetics of these two compartments were indeed distinct from those seen for naïve T cells, with a clear division between putative memory T cells and CD28− T cells. Furthermore, what was more interesting derived from observing separately each of these cell types in CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, either as absolute number (Fig. 5) or as percentage variation from baseline mean values (Fig. 6). First, albeit naïve T cells recovered with a quite similar pattern in CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, naïve CD4+ T cells did not return to values comparable to those seen at diagnosis (Fig. 6 and Table 1). By contrast, CD95+ CD28+ T cells gradually returned to median values not significantly different from those seen in patients at diagnosis (Table 1). Finally, CD28− T cells showed a peculiar behaviour since they recovered early after treatment by doubling baseline values at 3 months following HD-ChT and remained high (Fig. 6). Furthermore, CD28− T cells were the only cell type with values after treatment significantly higher than at diagnosis, they predominated within CD8+ T cells and accounted for the largest part of their increase. Thus, each cell type showed a distinct pattern of recovery consistent, respectively, with naïve T cells of thymic origin, memory T cells not recently activated and rapidly expanding CD28− effector T cells.

Figure 5.

Recovery dynamics of naïve, memory and CD28− T cells after HD-ChT. Box plots indicating median values with interquartiles are referred to data obtained from 20 patients at diagnosis (first box on the left of each plot) as well as 100 patients after HD-ChT. For each T-cell subset analysed, patients have been grouped according to time elapsed from HD-ChT to their phenotypic evaluation. Specifically, treated patients are referred to the following intervals from HD-ChT: 15 days (10 patients), 1–3 months (10 patients), 4–6 months (10 patients), 7–12 months (15 patients), 13–24 months (16 patients), 25–36 months (19 patients), and 37–65 months (20 patients). In order to provide visible evidence of differences among various T-cell subsets, scales of cell number/μl on the y-axis were kept identical across various plots.

Figure 6.

Recovery dynamics of naïve, memory and CD28− T-cell after HD-ChT analysed as percentage variation referred to baseline values. Mean value of data from 20 untreated patients at diagnosis represent the starting point on the left of each plot, whereas 100 patients who had undergone HD-ChT have been grouped according to time elapsed (in months, on x-axis) from HD-ChT to their phenotypic evaluation, as shown in Figure 5. For each naïve, memory, and CD28− subset, mean values from patients' groups at various time-points are expressed on the y-axis as percentage variation to absolute mean values observed in the control group at diagnosis (pre-ChT).

Table 1.

Comparison between 20 patients at diagnosis versus 20 patients evaluated 37–65 months after treatment with HD-ChT and autologous PBSC transplantation

| Diagnosis median (25–75%) [range] | Post-HD-ChT median (25–75%) [range] | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52·5 | 52·5 | 0·65 |

| (44·5–58) [36–65] | (51–56) [42–60] | ||

| CD3+ cells | 1280 | 1377 | 0·80 |

| (1027–1649) [510–2222] | (741–1570) [428–2920] | ||

| ″naïve | 514 | 185 | 0·0002* |

| (308–703) [229–1401] | (110–362) [41–822] | ||

| ″memory | 540 | 606 | 0·64 |

| (349–653) [228–787] | (325–714) [126–1734] | ||

| ″CD28− | 173 | 357 | 0·0008* |

| (99–249) [8–525] | (280–570) [44–867] | ||

| CD4+ T cells | 767 | 587 | 0·013* |

| (584–996) [325–1713] | (342–715) [128–1329] | ||

| ″naïve | 347 | 107·5 | 0·0001* |

| (248–530) [130–1234] | (67–198) [10–463] | ||

| ″memory | 364 | 347 | 0·61 |

| (281–422) [144–620] | (213–436) [88–1014] | ||

| ″CD28− | 17 | 54·5 | 0·007* |

| (4–42) [1–121] | (29–102) [2–292] | ||

| CD8+ T cells | 379 | 557 | 0·037* |

| (196–527) [103–657] | (349–701) [128–1314] | ||

| ″naïve | 92 | 54 | 0·074 |

| (66–136) [20–225] | (29·5–100) [7–278] | ||

| ″memory | 99 | 157 | 0·14 |

| (64–151) [37–320] | (78·5–228) [36–572] | ||

| ″CD28− | 101 | 249 | 0·0007* |

| (27–209) [7–386] | (210–414) [35–627] |

where P < 0·05 after analysis by two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test.

Long-term alterations of T-cell pool composition after HD-ChT and autologous PBSC transplantation

A group of subjects including 20 patients observed from 37 to 65 months after HD-ChT with autologous PBSC transplantation, was compared with an age-, sex- and pathology-matched group of 20 patients observed at diagnosis. Data refer to total T-cell counts, as well as CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, each including naïve, memory and CD28− compartments (Table 1). Total lymphocytes were not significantly different between the two groups, but T-cell pool composition was altered, since the naïve compartment was remarkably reduced (P = 0·0002) and CD28− T cells significantly increased (P = 0·0008) in the treated group. When we analysed separately CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, we found that CD4+ T cells were significantly reduced in the treated group because of the critical loss in the naïve compartment (about one-third of the control group), with a concomitant increase of CD28− T cells. By contrast, CD8+ T cells were slightly increased without significant loss of naïve cells, but with a significant increase in CD28− cells (2·5-fold compared to the control group). The memory compartment was not significantly different in the two groups either when considering T cells as a whole, or CD4+ and CD8+ subsets. On the whole, T cells recovered baseline values in the treated group, but T-cell pool composition was altered because of a profound loss in naïve CD4+ T cells, with a concomitant increase of CD28− T cells mainly due to expansion of CD8+ CD28− T cells. These alterations were observed 37–65 months after HD-ChT and therefore they may last longer or perhaps even persist permanently in such adult patients.

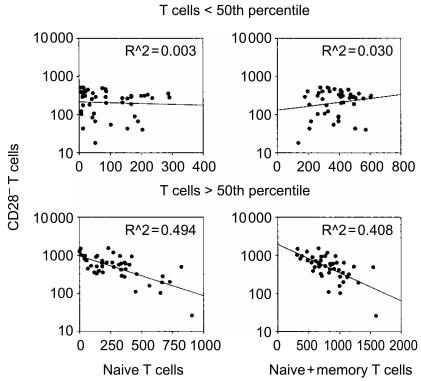

Role of CD28− T-cell expansion in T-cell homeostasis and alteration of CD4 : CD8 ratio

The dynamic of T-cell reconstitution suggested that CD28− T cells could play a role in recovering normal total T cell numbers in patients after T-cell depletion by HD-ChT. To test such a hypothesis, we measured correlation between CD28− T cells versus either naïve or memory cells alone, or their sum. In agreement with the assumption that CD28− T cells may compensate insufficient recovery of naïve or memory cells to maintain near to constant total T-cell numbers, the cohort was divided into two groups according to its median T-cell count (961 T cells/μl), thus arbitrarily assuming to distinguish between subjects that had and those that had not, reached T-cell homeostasis (Fig. 7). In patients with circulating T cells above the 50th percentile, we found that CD28− T cells increased logarithmically as the naïve T-cell counts (or their sum with memory cells) decreased (Fig. 7, lower panels). By contrast, we could not find a similar relationship either in the group with lower T cells numbers (Fig. 7, top panels), or by correlating CD28− T cells with memory cells in any of the two groups (not shown). Although this relationship between naïve and CD28− T cells needs to be verified in a perspective study, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that CD28− T cells expand to replenish the loss of naïve T cells and, given the relatively independent homeostasis of the memory T-cell pool, to maintain constant levels of total T-cell number. Interestingly, it should be noted that the largest number of naïve T cells was lost within the CD4+ subset, whereas the largest increase of CD28− T cells was observed within the CD8+ subset (Fig. 5). This remodelling pattern suggests that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells may be counted together for the purposes of maintaining constant T-cell numbers.

Figure 7.

Relationship between CD28− and naïve T cells following T-cell reconstitution. Data are shown from 100 treated patients that were divided into two groups according to total T-cell numbers. Absolute numbers of circulating CD28− T cells per μl (on the y-axis) were plotted as individual data points against naïve T cells (left column) or naïve plus memory T cells (right column) on the x-axis. R2 values were calculated by linear regression analysis.

Conversely, we speculated that loss of CD4+ naïve cells with concomitant CD28− expansion within the CD8+ subset could account for the alteration of the CD4 : CD8 ratio seen after HD-ChT. To test this hypothesis, we measured the correlation between numbers of CD8+ CD28− T cells and CD4 : CD8 ratios in patients recovering from HD-ChT and we found that approximately 54% of the variation affecting CD4 : CD8 ratio was inversely related to CD8+ CD28− T-cell numbers on a logarithmic basis (Fig. 8, top plot). Based on this observation in patients recovering from HD-ChT, we also tested whether CD8+ CD28− T-cell numbers could explain the variation in the CD4 : CD8 ratio in steady-state conditions, such as in patients with breast cancer at diagnosis as well as in healthy subjects. As shown in Fig. 8 on the bottom, CD8+ CD28− T-cell numbers explained only 34% of CD4 : CD8 reduction in our mixed cohort. Nevertheless, these data indicate that there is a significant inverse relationship on a log base between CD8+ CD28− T cells and the CD4 : CD8 ratio in physiological and/or steady-state conditions in adult people and that this relationship may be more significant when T-cell homeostasis is altered by T-cell depletion followed by predominant expansion of CD8+ CD28− T cells.

Figure 8.

Relationship between CD8+ CD28− T cells and CD4 : CD8 ratio. Data from 80 patients recovering from HD-ChT with > 500 T cells per μl (top dot plot) as well as from 60 subjects including 20 patients with breast cancer at diagnosis and 40 matched healthy subjects (bottom dot plot), are shown. Absolute numbers of circulating CD8+ CD28− T cells per μl (on the x-axis) were plotted as individual data points against CD4 : CD8 T-cell ratios on the y-axis. R2 values were calculated by logarithmic regression analysis. In order to provide visible evidence of differences between the two groups of subjects, the scales of both the y-axis and the x-axis were kept identical.

Discussion

This study was conducted to clarify the physiological response to acute and maximal T-cell depletion in human adults. To this end, we used three-colour immunophenotyping to obtain an overall picture of T-cell reconstitution after HD-ChT in women with high-risk breast cancer. Evaluation of putative naïve, memory and effector CD28− T cells was instrumental to one of the most innovative aspects of our study, namely the elucidation of the elusive CD8+ T-cell perturbation. Naïve and memory CD8 T-cell reconstitution appeared to follow patterns very similar to those described within CD4+ T-cell subsets. By contrast, CD28− T cells accounted for the main differences observed between CD8+ and CD4+ cells, including an altered CD4 : CD8 ratio.

The main limitation of this study is the absence of sequential data for detailed analysis of trends in such a long interval considered (> 5 years after HD-ChT). Indeed, such a cross-sectional study necessarily included wide interpatient variation and the age representations at various time-points were not the same, with obvious implications for evaluation of thymic recovery. For instance, when similarly evaluating normal subjects on a cross-sectional basis, we found an average age-dependent loss of 8·4 ± 0·7 CD95− CD28+ naïve T cells per year, with a concomitant gain of 1·6 ± 0·6 CD28− cells per year.14 Nevertheless, even when considering these limitations of the study protocol design, it should be noted that the dynamics of the three cell types analysed were distinct for each cell compartment, and surprisingly consistent with their own homeostatic regulation. Accordingly, such dynamics were also convincingly concordant with the respective origin and function of naïve, memory and effector cells, thus further sustaining the accuracy of the relationship with the phenotypic definition.

Confirming our working hypothesis, reconstitution within the CD8+ T-cell subset after cytotoxic chemotherapy has been determined thanks to separate analysis of CD28− T cells. As already reported, also by others, expansion of CD28− CD57+ cells can account for the post-treatment early increase of total CD8+ T cells, as compared to CD4+ cells.22 Similarly, in patients treated for Hodgkin's Disease, the appearance of unusual cells with aberrant phenotype was interpreted as a consequence of impaired thymic function resulting from mediastinal irradiation.23 In patients with HIV infection, CD8+ CD28− T cells correlate inversely to CD4+ and to CD8+ CD28+ T cells and thus contribute to T-cell homeostasis,24 but it is uncertain whether an increase in effector cells may rather depend on ongoing anti-HIV immune responses.25 In our analysis, we found that CD28− T cells provided rapid fill up of the space emptied by chemotherapy, accounting for the largest early T-cell increase (Figs 5 and 6) and for T-cell homeostatic regulation to compensate naïve and memory T-cell losses (Fig. 7). Such compensation did not distinguish between CD4+ and CD8+ subsets (so-called ‘blind’ T-cell homeostasis3) (Fig. 7) and induced CD4 : CD8 imbalance (Fig. 8). On the whole, although how T cells may be counted in the periphery is still unclear, our study showed that acute T-cell depletion was quantitatively compensated by replenishment with CD28− T cells that played a pivotal role in maintaining near to constant T-cell numbers, but significantly altered the CD4 : CD8 ratio.

What the origin may be of CD28− T-cell expansion in peripheral blood at present remains only speculative. As far as we can conceive, there are two main possibilities for such a rapid increase over a period of days or weeks. First, they could derive from antigen-driven clonal expansion by rapid transitional cell proliferation26 that would be necessarily skewed towards the driving antigens.6 Alternatively, they could derive simply by mobilization to peripheral blood from peripheral tissues where effector T cells are reported to be broadly distributed27,28 and to/from which they may possibly recirculate.29 Apart from the origin, the biology of these cells is quite well defined. At the functional level, although these cells may not be homogeneous, they are reported as terminally differentiated cytotoxic effector cells ready to exert anti-CD3 redirected cell cytotoxicity,19 and secrete large amounts of interferon-γ.30 As far as the antigen specificity is concerned, CD8 expression implies an human leucocyte antigen class-I restriction for pathogens of intracellular origin that limits possible hypotheses to persistent ubiquitous viruses such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, herpes zoster virus, etc.

In contrast to CD28− T cells, it must be noted that the kinetics of putative memory cells observed in our patients was consistent with the notion that they reconstituted by regenerative mitotic cell division. Regenerative mitotic cell division, as opposed to clonal expansion deriving from transitional cell division, is slow and stochastic, it takes months or years, daughter cells maintain phenotype, viability and proliferative capacity, and it is critical for reconstitution and/or maintenance of the memory T-cell pool necessary to the efficiency of recall immune responses.26 In addition, although we did not investigate recall T-cell responses in our patients, the extended phenotype and the co-stimulatory requirement (not shown) were also consistent with the hypothesis that these cells should bear the memory of previously encountered antigens. Finally, but not less importantly, each CD4+ and CD8+ putative memory population appeared to recover gradually without expanding beyond their own pretreatment values, without influence form either other cell types, or age. Considering these latter aspects, we favour the hypothesis that memory cells may occupy their own separated niches for CD4+ and CD8+ subsets, as has been elegantly demonstrated in mice.31,32 Similarly, by studying normal subjects, we found constant levels of CD95+ CD28+ cells from young adulthood to advanced age.14 The speculative concept emerging from that study and from data shown here, is that the quantity of circulating memory cells is carefully monitored and kept constant, even though conditions acting chronically, such as physiological aging, or acting acutely, such as cytotoxic therapy, reduce the whole ‘immunological space’.33

The definition of thymic-dependent lymphopoiesis and the estimation of the naïve T-cell reservoir are matters of intense basic and clinical research. Recently, identification of T-cell Receptor Excision Circles (TREC) has revolutionized this field by allowing the evaluation of most T cells that have undergone effective α/β T-cell receptor (TCR) rearrangement after aborting γ/δ TCR rearrangement.34 At present, the main limitations in TREC analysis are due to failure of direct single-cell phenotypic analysis, to possible regenerative cell division that may affect TREC cell content,35 and to possible extrathymic lymphopoiesis.36 Nevertheless, TREC analysis has opened new avenues of investigation, including the recent demonstration that TREC contents in a cohort of adult myeloma patients treated with HD-ChT and autologous PBSC could predict T-cell reconstitution.13 Remarkably, TREC content was found to be parallel in CD4+ and CD8+ subsets and to be inversely related to patient age.13 Data presented here complete and extend these latter findings, indicating that phenotypic naïve T cells had an age-dependent (Fig. 3) and delayed recovery with tight CD4 : CD8 correlation, consistent with their putative thymic origin. Thus, our data support the assumption that not only naïve CD4+, but also naïve CD8+ cells, can be neogenerated after HD-ChT and that thymus can still contribute significantly to naïve T-cell reconstitution even at ages ranging from 25 to 55 years.

Notwithstanding substantial naïve T-cell regeneration, naïve cell loss was revealed to be far from healed in our adult patients even 3–5 years from HD-ChT (Table 1). In fact, despite an apparent recovery in total T-cell numbers, we found that significant alterations persisted beyond this time limit since CD4+ naïve T cells were still much lower than at diagnosis, with a concomitant increase of CD28− T cells. Somehow surprisingly, naïve CD8+ T cells were not significantly lower than in patients at diagnosis, thus showing clearly a different pattern from naïve T-cell depletion occurring with physiological advanced aging characterized by a predominant loss of naïve CD8+ cells.14 In any event, with increasing age, the common Achille's heel facing acute and/or chronic T-cell depletion appears to be constituted by insufficient recovery of naïve T-cell counts.

The study presented here may have conceptual and practical implications. At the conceptual level, our observations are consistent with the emerging concept of a reciprocal interplay between T-cell ‘blind’ homeostasis and independent homeostatic regulation of naïve and memory T cells within their own separate niches.1 At the practical level, these findings may contribute to explain clinical observations in adult patients given HD-ChT who, despite recovered T-cell numbers, cannot be immunized efficiently for at least 6–12 months, whereas they maintain sufficient immunological memory. In fact, in contrast to naïve and memory T cells, CD28− cells cannot be considered effective for either novel or recall antigens, because of their specific biology and restricted repertoire. On this basis, we suggest that for general quantitative assessment of immune competence, effector CD28− T cells should be considered separately. More specifically, if we have to explore active immunotherapy against tumour antigens in cancer patients,37,38 we have to consider that cytotoxic chemotherapy remains the most effective therapeutic approach for treating a large number of malignancies. Consequently, the apparently complex T-cell remodelling following HD-ChT here described might be helpful in choosing the appropriate approach and timing for therapeutic vaccination trials in patients previously treated with chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Franco Locatelli for his critical review of the manuscript. We also thank Orietta Moscato and all the nurses and personnel of the Medical Oncology Division for their assistance with patients and their help in the collection of blood samples.

References

- 1.Goldrath AW, Bevan MJ. Selecting and maintaining a diverse T-cell repertoire. Nature. 1999;402:255–62. doi: 10.1038/46218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanchot C, Rocha B. The organization of mature T-cell pools. Immunol Today. 1998;19:575–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margolick JB, Munoz A, Donnenberg AD, et al. Failure of T-cell homeostasis preceding AIDS in HIV-1 infection. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Nat Med. 1995;1:674–80. doi: 10.1038/nm0795-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amadori A, Zamarchi R, De Silvestro G, et al. Genetic control of the CD4/CD8 T-cell ratio in humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:1279–83. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall MA, Ahmadi KR, Norman P, Snieder H, MacGregor AJ, Vaughan RW, Spector TD, Lanchbury JS. Genetic influence on peripheral blood T lymphocyte levels. Genes Immun. 2000;1:423–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackall CL, Bare CV, Granger LA, Sharrow SO, Titus JA, Gress RE. Thymic-independent T cell regeneration occurs via antigen-driven expansion of peripheral T cells resulting in a repertoire that is limited in diversity and prone to skewing. J Immunol. 1996;156:4609–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fry TJ, Connick E, Falloon J, Lederman MM, et al. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–90. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storek J, Dawson MA, Storer B, et al. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic marrow transplantation compared with blood stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2001;97:3380–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehne G, Zeller W, Stockschlaeder M, Zander AR. Phenotype of lymphocyte subsets after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:149–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Symann M. Immune reconstitution and immunotherapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:1471–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:143–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heitger A, Neu N, Kern H, et al. Essential role of the thymus to reconstitute naïve (CD45RA+) T-helper cells after human allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1997;90:850–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douek DC, Vescio RA, Betts MR, et al. Assessment of thymic output in adults after haematopoietic stem-cell transplantation and prediction of T-cell reconstitution. Lancet. 2000;355:1875–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagnoni FF, Vescovini R, Passeri G, et al. Shortage of circulating naïve CD8 (+) T cells provides new insights on immunodeficiency in aging. Blood. 2000;95:2860–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zibera C, Pedrazzoli P, Ponchio L, et al. Efficacy of epirubicin/paclitaxel combination in mobilizing large amounts of hematopoietic progenitor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer showing optimal response to the same chemotherapy regimen. Haematologica. 1999;84:924–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fagnoni FF, Oliviero B, Zibera C, et al. Circulating CD33+ large mononuclear cells contain three distinct populations with phenotype of putative antigen-presenting cells including myeloid dendritic cells and CD14+ monocytes with their CD16+ subset. Cytometry. 2001;45:124–32. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20011001)45:2<124::aid-cyto1154>3.0.co;2-l. 10.1002/1097-0320(20011001)45:2124::AID-CYTO11543.3.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Rosa SC, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA, Roederer M. 11-color, 13-parameter flow cytometry: identification of human naïve T cells by phenotype, function, and T-cell receptor diversity. Nat Med. 2001;7:245–8. doi: 10.1038/84701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azuma M, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. CD28− T lymphocytes. Antigenic and functional properties. J Immunol. 1993;150:1147–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fagnoni FF, Vescovini R, Mazzola M, et al. Expansion of cytotoxic CD8+ CD28− T cells in healthy ageing people, including centenarians. Immunology. 1996;88:501–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posnett DN, Sinha R, Kabak S, Russo C. Clonal populations of T cells in normal elderly humans: the T cell equivalent to ‘benign monoclonal gammapathy’. J Exp Med. 1994;179:609–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakim FT, Cepeda R, Kaimei S, et al. Constraints on CD4 recovery postchemotherapy in adults: thymic insufficiency and apoptotic decline of expanded peripheral CD4 cells. Blood. 1997;90:3789–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Distinctions between CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell regenerative pathways result in prolonged T-cell subset imbalance after intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 1997;89:3700–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe N, De Rosa SC, Cmelak A, Hoppe R, Herzenberg LA, Roederer M. Long-term depletion of naïve T cells in patients treated for Hodgkin's disease. Blood. 1997;90:3662–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caruso A, Licenziati S, Canaris AD, et al. Contribution of CD4+, CD8+CD28+, and CD8+CD28− T cells to CD3+ lymphocyte homeostasis during the natural course of HIV-1 infection. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:137–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiorentino S, Dalod M, Olive D, Guillet JG, Gomard E. Predominant involvement of CD8+CD28− lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus-specific cytotoxic activity. J Virol. 1996;70:2022–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.2022-2026.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grossman Z, Paul WE. The impact of HIV on naïve T-cell homeostasis. Nat Med. 2000;6:976–7. doi: 10.1038/79667. 10.1038/79667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masopust D, Vezys V, Marzo AL, Lefrancois L. Preferential localization of effector memory cells in nonlymphoid tissue. Science. 2001;291:2413–17. doi: 10.1126/science.1058867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoshino T, Yamada A, Honda J, et al. Tissue-specific distribution and age-dependent increase of human CD11b+ T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2237–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–12. doi: 10.1038/44385. 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nociari MM, Telford W, Russo C. Postthymic development of CD28–CD8+ T cell subset: age-associated expansion and shift from memory to naïve phenotype. J Immunol. 1999;162:3327–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freitas AA, Rocha B. Peripheral T cell survival. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:152–6. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ku CC, Murakami M, Sakamoto A, Kappler J, Marrack P. Control of homeostasis of CD8+ memory T cells by opposing cytokines. Science. 2000;288:675–8. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franceschi C, Valensin S, Fagnoni F, Barbi C, Bonafe M. Biomarkers of immunosenescence within an evolutionary perspective: the challenge of heterogeneity and the role of antigenic load. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34:911–21. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Douek DC, McFarland RD, Keiser PH, et al. Changes in thymic function with age and during the treatment of HIV infection. Nature. 1998;396:690–5. doi: 10.1038/25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hazenberg MD, Otto SA, Cohen Stuart JW, et al. Increased cell division but not thymic dysfunction rapidly affects the T-cell receptor excision circle content of the naïve T cell population in HIV-1 infection. Nat Med. 2000;6:1036–42. doi: 10.1038/79549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Storek J, Storb R. T-cell reconstitution after stem-cell transplantation – by which organ? Lancet. 2000;355:1843. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu FJ, Benike C, Fagnoni F, et al. Vaccination of patients with B-cell lymphoma using autologous antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1996;2:52–8. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagnoni FF, Robustelli della Cuna G. Immunotherapy on the edge between experimental and clinical oncology. J Chemother. 2001;13:15–23. doi: 10.1179/joc.2001.13.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]