Abstract

Immunization of mice with activated antigen-presenting cells (APC) pulsed ex vivo with cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide, a glucuronoxylomannan (GXM-APC) results in prolongation of survival and delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) responsiveness following infection with Cryptococcus neoformans (NU-2). GXM-APC has both non-specific and GXM-specific effects that influence the immune responses that develop in mice after infection with NU-2. Type 1 cytokine responses are augmented after immunization with APC alone, while GXM must be present for the vaccine to influence survival and DTH reactions. This investigation evaluated the role that major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and co-stimulatory molecules play in the non-specific and GXM-specific responses induced by GXM-APC. APC from CD40 knockout mice were as effective as wild-type APC for the induction of non-specific and GXM-specific responses. Blocking activity of B7-1 and B7-2 by treatment of immunized mice with monoclonal antibodies specific for these molecules just before and for 6 days following GXM-APC immunization decreased the splenic interferon-γ response of mice subsequently infected with NU-2, but only in mice that were treated with both antibodies. These antibody treatments had no effect on DTH reactivity in similarly treated animals. MHC class I molecules were not involved in the antigen non-specific or GXM-specific activities of the vaccine. MHC class II molecules were not required for augmentation of type 1 cytokine responses but were needed for induction of the GXM-specific response that regulates the expression of DTH reactivity. This investigation has shown that an MHC class II-restricted, GXM-specific response is responsible for altering DTH responsiveness which is the correlate of immunity in this model.

Introduction

The immune responses of mice infected with a highly virulent isolate of Cryptococcus neoformans (NU-2) are distinguished by an initial responsive phase characterized by production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-2 (IL-2) and IL-10 by spleen cells stimulated in vitro with cryptococcal antigen and by positive delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions to soluble cryptococcal antigen1in vivo. The responsive phase is followed by an unresponsive phase that persists until the death of the animals. The unresponsive phase cannot be attributed to development of a type-2 (IL-4 or IL-10) cytokine response and appears to be the result of induction of other suppressive mechanisms, anergy and/or deletion of responsive clones in the infected mice. The highly virulent cryptococcal isolate (NU-2) secretes large amounts of capsular polysaccharide, a glucuronoxylomanan (GXM), in vivo, as measured by serum GXM levels, and these levels are correlated with the induction of the unresponsiveness that occurs after infection with this isolate.1

We previously reported that the unresponsive phase that occurs after infection with the highly virulent cryptococcal isolate (NU-2) is associated with the induction of CD8+ regulatory T cells that are specific to the capsular polysaccharide of the organism.2–4 These GXM-specific regulatory T cells are responsible for triggering immunoregulatory circuits that ultimately produce antigen non-specific mediators capable of inhibiting the expression of the DTH response to any antigen.5 In other words, the specific response to one cryptococcal antigen, GXM, can inhibit the response to protein-containing antigens of the organism, such as those found in the mannoprotein fraction, that are responsible for eliciting the DTH response. Type 1 cytokine responses and classical DTH reactions to the mannoprotein fraction of C. neoformans are associated with protective immunity to this pathogen.6,7

The GXM-specific immunosuppressive response is inhibited in mice that are immunized with activated antigen-presenting cells (APC) pulsed ex vivo with GXM (GXM-APC).8 GXM-APC immunized mice survive longer than sham-immunized mice after infection with the cryptococcal isolate NU-2. Infected, GXM-APC-immunized mice maintain their anti-cryptococcal DTH response longer than do infected, sham-immunized mice and therefore, prolonged DTH reactivity is correlated with enhancement of immunity in this model.8 For this reason DTH reactivity can be followed to study the mechanism responsible for enhancement of protection provided by GXM-APC immunization.

An analysis of the ability of mannoprotein-stimulated spleen cells from GXM-APC- and APC-immunized mice to secrete type-1 and type-2 cytokines revealed that both treatments allow mice to respond to a subsequent cryptococcal infection with an improved type-1 (IL-2 and IFN-γ) cytokine response.9 These studies delineated two separate activities that are supplied by the GXM-APC immunization. First, a GXM-independent immunomodulatory response is provided by the activated APC population used to prepare the GXM-APC. This GXM-independent activity is responsible for the enhanced T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokine responses that develop in the infected mice.9 The second activity provided by GXM-APC immunization improves protective immunity and is characterized by prolonging the period of positive DTH reactivity in infected mice. While the antigen non-specific immunomodulatory activity does not enhance protection by itself,8 cytokines secreted during the non-specific response may be needed for the induction of the GXM-specific response.

During infection with NU-2, CD8+ regulatory T cells, induced by high levels of soluble GXM, inhibit the expression of DTH reactivity by the DTH-responsive CD4+ T cells (TDTH).10 GXM-APC immunization induces a GXM-specific response that inhibits the induction and/or the expression of regulatory T cells, thereby preserving the expression of the mannoprotein-specific DTH response that develops in the infected mice.

The current investigation was undertaken to define further the APC signals that are responsible for the non-specific and GXM-specific effects of the GXM-APC immunization. The results of this study showed that the non-specific effects of the infused APC population did not depend on expression of CD40, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules or MHC class II molecules by the APC population but could be partially blocked by combined treatment of APC-treated mice with anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2. Induction of the GXM-specific regulatory response that influences the expression of DTH reactions was dependent upon the presence of MHC class II and was independent of the presence of B7, CD40 and MHC class I on the APC membrane.

Materials and methods

Animals

C57BL/6J, C57BL/6Ncr-Tnfrsf5tm1Kik (CD40 knockout) and CBA/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME. MHC class I (C57BL/6GphTac-β2mtm1) and MHC class II (C57BL/6Tac-Abbtm1) -deficient mice were purchased from Taconic Farms, Germantown, NY. All mice were received when they were 8 weeks old and were used in experiments when they were 12–14 weeks old. The mice were housed in the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Animal Facility that is accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All experimental protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Reagents

Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), HEPES, penicillin–streptomycin, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol, sodium pyruvate, l-glutamine, essential vitamins and non-essential amino acids were purchased from Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY). HyClone (Ogden, UT) was the supplier of fetal bovine serum (FBS). Concanavalin A, RPMI-1640 and complete Freund's adjuvant were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). PharMingen (San Diego, CA) supplied recombinant mouse IL-2 and IFN-γ and paired monoclonal antibodies specific for these cytokines that were used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

Fungal strains

The C. neoformans isolate used for infection of mice was NU-2, which was originally obtained from the spinal fluid of a patient at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Cryptococcal skin test antigen was prepared from isolate 184A, obtained from Dr Juneann Murphy, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. Both isolates are serotype A.

Maintenance of endotoxin-free conditions

To ensure that endotoxin contamination was not a factor in our experiments, all procedures were performed under conditions that minimized endotoxin contamination. Endotoxin-free plasticware was used whenever possible and glassware was heated for 3 hr at 180°. All reagents contained less that 1 endotoxin units (EU) of endotoxin/ml (minimal detectable level) in the chromogenic Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (Whittaker Bioproducts, Inc., Walkersville, MD).

Preparation of cryptococcal antigen

A cryptococcal culture filtrate antigen (CneF) was prepared from isolate 184A as described by Buchanan and Murphy.11 The preparation used in this investigation had a protein content of 252·3 μg/ml (primarily cryptococcal mannoproteins) as determined by the bicinchoninic assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) and a carbohydrate concentration of 5 mg/ml as determined by the phenol–sulphuric assay.12 Using the Limulus assay, this lot of CneF had a reaction equivalent to 12·9 EU of endotoxin/ml. This extract was added to spleen cell cultures at a 1 : 20 dilution, therefore it added 0·64 EU/ml of culture. Because the extract contained a high concentration of cryptococcal GXM, which gives a positive reaction in the Limulus assay because of its content of glucuronic acid,13 the Limulus reactivity in the CneF preparation is considered to be a result of glucuronic acid rather than endotoxin contamination.

Cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide (GXM) was prepared as described previously.14 This lot of polysaccharide contained 0·05 EU/ml in a solution of GXM containing 100 μg/ml polysaccharide (tested by BioWhittaker after blocking the contribution of β-glucans). To test for the ability of GXM to influence the state of activation of the APC, GXM was tested for its ability to modulate cytokine mRNA levels of the activated peritoneal exudate cells (PEC) that were induced with complete Freund's adjuvant (method described below). RNA extracts obtained from PEC incubated for 5 hr in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml GXM were assayed for cytokine mRNA levels using a commercially available RNAase protection kit (PharMingen). The results of this analysis showed that the polysaccharide did not augment or inhibit PEC mRNA expression of IL-12 p35, IL-12 p40, IL-10, IL-1β, interferon-gamma inducing factor (IGIF), IL-6, IFN-γ and migration-inhibitory factor (MIF) as compared to PEC that were incubated for 5 hr in medium without GXM stimulation.

Preparation of GXM-APC

Normal mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0·5 ml of un-emulsified complete Freund's adjuvant. Five days later the peritoneal exudate cells were harvested with PBS containing 1% FBS. After the cells had been washed twice with PBS, they were resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg streptomycin/ml. GXM was added to a portion of the cells at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml. The remaining cells were incubated in medium without addition of GXM. The cells were incubated for 1 hr at 37° in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Following this incubation the cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in PBS to a concentration of 1 × 107 viable cells/ml. Recipient animals were immunized by injection of 5 × 106 cells intravenously.

Experimental protocol

Animals were injected intravenously with GXM-APC or APC 7 days prior to infection with 1 × 104 (cytokine analysis in C57BL/6 mice) or 1 × 105 (cytokine analysis in CBA/J mice and DTH analysis in both strains) C. neoformans (NU-2) as indicated. Some experiments included APC donors that had deletions of genes which resulted in phenotypes lacking expression of CD40, MHC class I, or MHC class II molecules. Controls included naïve animals that were infected without previous treatment with APC and sham-infected, normal mice that were not immunized and were given 25 μl of PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Initial kinetic analysis in C57BL/6 mice showed that peak cytokine responses occurred on the 10th to 15th days after infection with 1 × 104 NU-2. CBA/J mice infected with 1 × 105 organisms also exhibited peak cytokine responses by the 10th to 15th days of infection. As a result of fluctuations in the kinetics of the infectious process the analysis of cytokine responses was routinely performed at the 10th and 15th day after infection so that the peak response would not be missed. The data presented represent the peak cytokine response obtained for individual experiments. In some experiments, the ability of CneF to elicit an anti-cryptococcal DTH response was tested in mice 16 days (C57BL/6 mice) or 21 days (CBA/J mice) after infection with 1 × 105 NU-2. During infection with the NU-2 cryptococcal isolate, mice develop a transient DTH response that was followed by DTH unresponsivness.1 GXM-APC administration prolongs the responsive state. Previous investigations in C57BL/6 and CBA/J mice8 established the time-points of the unresponsive phase of these mice after intratracheal infection with 1 × 105 NU-2. In C57BL/6J mice the unresponsive phase usually occurred by the 15th day of infection and in CBA/J mice unresponsiveness occurred by the 20th day of infection. The time of assay of the DTH response was chosen to ensure that infected control mice had entered the unresponsive phase.

Preparation and treatment with anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2

Hybridoma cell lines that secrete anti-B7-1 (CRL 2223) and anti-B7-2 (CRL 2226) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. The cell lines were grown in commercially available CELLine flasks obtained from Integra Biosciences, Inc., Ijamsville, MD. Immunoglobulins in culture supernatants were isolated by affinity chromatography using an ImmunoPure(G) immunoglobulin G (IgG) purification kit (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After dialysis against PBS the protein content of the solution was determined by the method of Kalckar15 and adjusted with PBS to contain 1·0 mg/ml protein. Mice treated with anti-B7 were given 100 μg of individual antibodies or with 100 μg of both antibodies by intraperitoneal injection. GXM-APC immunized control mice were treated with 200 μg of normal rat immunoglobulin (ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA). The mice were injected 1 hr before immunization with GXM-APC and on the 3rd and 6th days after immunization. This treatment regimen was shown to be effective in inhibiting the induction of contact sensitivity to the hapten picryl chloride (data not shown).

In vitro stimulation of cytokine synthesis by spleen cells

Spleen cells were harvested from individual mice and single cell suspensions were prepared by pressing the spleens through a sterile 60-mesh wire screen into sterile PBS containing 1% FBS. The cells were washed three times in PBS and resuspended in Bretcher's medium (RPMI-1640 containing 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 25 mm HEPES, 5 × 10−3 m 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm l-glutamine, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, 1% essential vitamins, 1% non-essential amino acids, and 10% FBS). Spleen cells at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml were stimulated with cryptococcal CneF (at a final dilution of 1 : 20) or they were cultured without stimulation to determine the constitutive or background level of cytokine secretion. Positive controls consisted of cells stimulated with 10 μg/ml concanavalin A (data not shown). Cultures were incubated at 37° in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, and supernatant fluids were collected 24 hr and 48 hr after the initiation of culture.

Quantification of cytokine levels in culture supernatants

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for detection of IL-2 and IFN-γ in tissue culture supernatants were constructed using commercially available paired monoclonal antibodies for each cytokine (PharMingen) according to our previously described method.1 IL-2 levels were measured in 24 hr supernatant fluids and IFN-γ levels were measured in the 48 hr supernatant fluids. The minimal levels of detection of IL-2, and IFN-γ assays were 31·9 pg/ml and 125 pg/ml, respectively.

Elicitation of the anti-cryptococcal DTH response

Hind footpads of mice were measured with a gauge micrometer (Starrett, Athol, MA). PBS (30 μl) was injected into the left footpad, and CneF (30 μl) was injected into the right footpad. The footpads were measured again 24 hr later. The increase in footpad thickness was calculated as the difference in swelling between the 0- and 24-hr measurements. Specific DTH reactivity was calculated as the difference between the swelling of the CneF-injected footpads and the swelling of the PBS-injected footpads.

Statistical analysis

Differences between experimental groups were evaluated by Student's t-test. Data with a P-value of 0·05 or less were considered to be significantly different. Each experiment was performed a minimum of twice.

Results

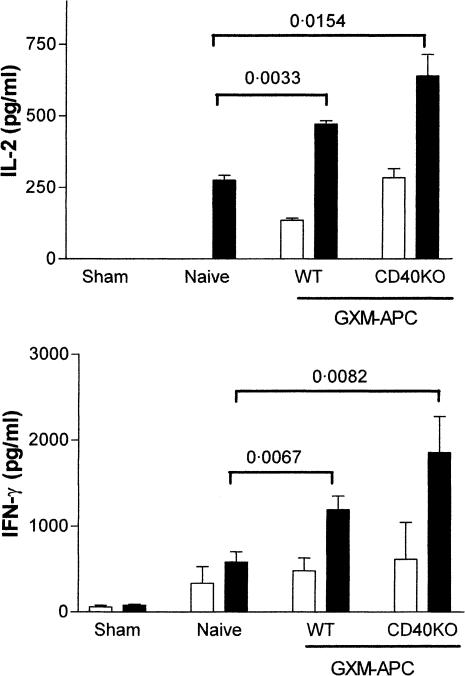

Determination of the role of CD40 for induction of enhanced type-1 cytokine responses in NU-2-infected mice that are immunized with GXM-APC

Expression of CD40 by APC is known to be necessary for induction for immunity to some pathogens.16–18 Therefore, it seemed possible that CD40 could play a role in the immunomodulatory activities provided by GXM-APC. The contribution that CD40 plays in the induction of the antigen-non-specific immunomodulatory effects of GXM-APC immunization was evaluated by comparison of GXM-APC prepared with peritoneal exudate cells derived from wild-type (C57BL/6J) or CD40 knockout mice. Mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 106 GXM-APC prepared with APC derived from wild-type or CD40 knockout mice. The mice were infected intratracheally 1 week later with 1 × 104 NU-2. Spleen cell cultures were analysed for type-1 cytokines 15 days after infection (Fig. 1). IL-2 and IFN-γ responses were significantly increased in mice that were immunized with GXM-APC as compared to naïve mice that were not immunized. There was no difference in the response of mice that were immunized with GXM-APC using wild-type or CD40 knockout APCs.

Figure 1.

Role of CD40 in augmenting Th1 cytokine responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Open bars, spleen cells cultured in medium; solid bars, spleen cells cultured in medium containing cryptococcal CneF antigen. Sham-infected mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naïve mice were not immunized but were infected. Immunized and infected mice were immunized with GXM-APC obtained from wild-type (WT) mice or from CD40 knockout (CD40KO) mice. Peak responses, which occurred on day 15 of infection, are shown. IL-2 data are means ± standard errors of the means for three to five individual C57BL/6J mice per group. IFN-γ data are means ± standard errors of the means for eight or nine individual C57BL/6J mice per group.

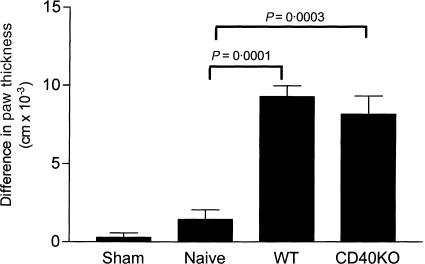

Determination of the role of CD40 for induction of prolonged DTH reactivity in NU-2-infected mice that are immunized with GXM-APC

The influence of CD40 expression by the APC component of GXM-APC was evaluated for its ability to prolong DTH reactivity in infected mice that were immunized with GXM-APC. Mice were immunized with GXM-APC prepared with APCs from CD40 knockout mice and from wild-type mice. The mice were infected intratracheally 1 week later with 1 × 105 NU-2 and tested for their DTH response to cryptococcal CneF at day 16 after infection. GXM-APC prepared with CD40 knockout peritoneal exudate cells were as effective as GXM-APC prepared with peritoneal exudates of wild-type mice in regulating DTH responses in NU-2-infected mice (Fig. 2). Thus, CD40 was not required for induction of the GXM-specific response.

Figure 2.

Role of CD40 in prolonging DTH responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Sham-infected mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naïve mice were not immunized but were infected. Immunized and infected mice were treated with GXM-APC obtained from wild-type (WT) mice or from CD40 knockout (CD40KO) mice. Mice were skin tested with cryptococcal CneF 16 days after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for seven individual C57BL/6J mice per group.

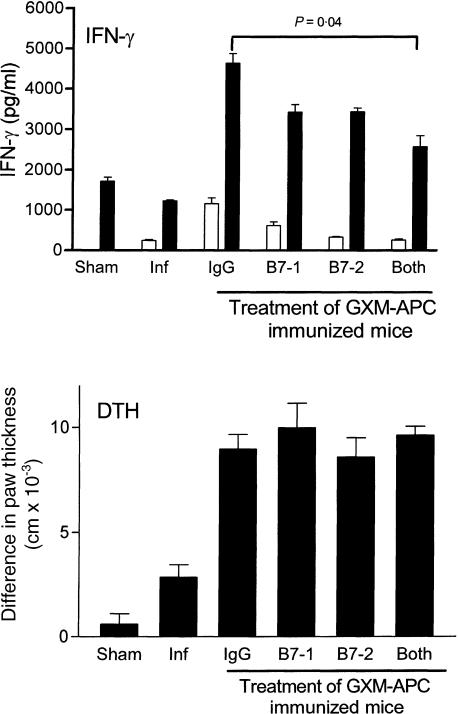

Determination of the role of B7 in the induction enhanced Th1 responses and prolonged DTH reactivity that occurs in NU-2-infected mice that are immunized with GXM-APC

For induction of immunity to protein antigens the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules B7-1 and/or B7-2 is essential to trigger T-cell responses.19 For this reason, we evaluated the contribution of B7-1 and B7-2 to the immunomodulatory activities provided by GXM-APC immunization. Mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of anti-B7-1, 100 μg of anti-B7-2, or 100 μg of both antibodies. These doses of the antibodies were previously shown to inhibit the induction of contact sensitivity to the hapten picryl chloride (data not shown). Each mouse received three doses of antibody. One dose was given 1 hr prior to GXM-APC immunization and the other two were administered on the 3rd and 6th days after immunization. Controls received 200 μg of normal rat immunoglobulin delivered on the same schedule. To ensure that the antibodies would not interfere with the immune response induced by the subsequent NU-2 infection, the mice were infected 8 days following the last injection of antibody. Fifteen days after infection spleen cells were removed from the mice and cultured in the presence or absence of CneF. IFN-γ levels were determined in 48-hr supernatants to evaluate the Th1 cytokine response of the mice (Fig. 3). Treatment of GXM-APC immunized mice with anti-B7-1 or B7-2 decreased the IFN-γ response, but this decrease was not significantly different from that in mice treated with normal rat immunoglobulin. When both antibodies were given there was a statistically significant decrease in the IFN-γ response but the IFN-γ response was not completely inhibited. DTH reactivity to cryptococcal CneF skin test antigen was evaluated in similar groups of mice that where treated with anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2 or both antibodies. The results are seen in Fig. 3. Treatment with anti-B7 antibodies did not influence the DTH reactivity of the infected, GXM-APC-immunized mice.

Figure 3.

Role of B7-1 and B7-2 in augmenting IFN-γ response and prolonging DTH reactions in GXM-APC-immunized mice. For the IFN-γ analysis open bars represent spleen cells cultured in medium and solid bars represent spleen cells cultured in medium containing cryptococcal CneF antigen. Sham-infected mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naive mice were not immunized but were infected. Immunized and infected mice were treated with 200 μg normal rat immunoglobulin (IgG), 100 μg anti-B7-1, 100 μg anti-B7-2, or 100 μg anti-B7-1 and 100 μg anti-B7-2. Antibody reagents were administered on the day of immunization and days 3 and 6 after immunization. Peak IFN-γ responses, which occurred on day 15 of infection, are shown. DTH responses were measured on the 16th day after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for three to five individual CBA/J mice per group for cytokine analysis and seven or eight individual mice for the DTH analysis.

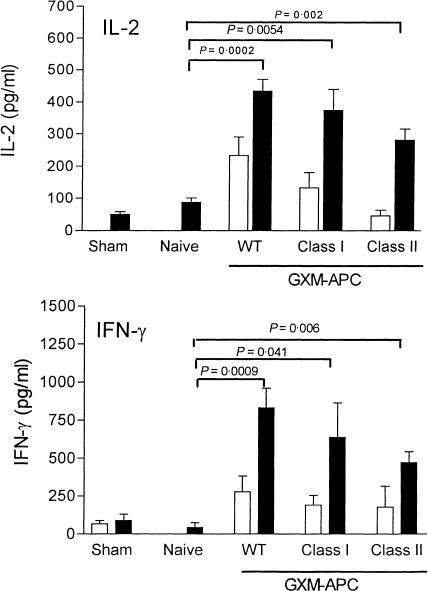

Determination of the role for MHC molecules in the induction of enhanced type-1 cytokine responses in NU-2-infected mice that were immunized with GXM-APC

To determine the roles that MHC class I and MHC class II molecules play in enhancement of type-1 cytokines responses by GXM-APC immunization, mice were immunized with GXM-APC prepared with APC derived from wild-type C57BL/6 mice or from knockout mice that did not express either MHC class I molecules or MHC class II molecules. One week after immunization the mice were infected intratracheally with 1 × 104 NU-2. Cytokine levels in these mice peaked at the 14th day of infection and the results are shown in Fig. 4. GXM-APC vaccines from all three strains of mice were equally effective in increasing the IL-2 and IFN-γ responses in infected mice revealing that the cytokine responses occurred in a manner that was independent of MHC expression on the APC membranes. While there was a trend toward slightly lower cytokine responses in mice that were immunized with GXM-APC that were derived from class I and class II knockout mice, these differences were never statistically significant. Evaluation of GXM-APC prepared from mice deficient for both MHC class I and MHC class II molecules also showed a slight reduction in the type-1 cytokine response but this difference was also not significant (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Role of MHC class I and class II molecules in augmenting Th1 cytokine responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Open bars, spleen cells cultured in medium. Solid bars, spleen cells cultured in medium containing cryptococcal CneF antigen. Sham-infected mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naive mice were not immunized but were infected. Immunized and infected mice were immunized with GXM-APC obtained from wild-type (WT) mice, MHC class I deficient mice (Class I) or MHC class II deficient mice (Class II). Peak responses, which occurred on day 14 of infection, are shown. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for three to five individual C57BL/6J mice per group.

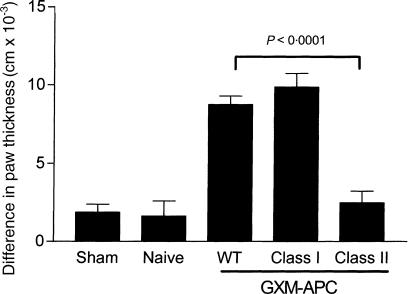

Determination role for MHC molecules for induction of prolonged DTH reactivity in NU-2-infected mice that were immunized with GXM-APC

Mice that were immunized with GXM-APC prepared with wild-type APC, MHC class I knockout APC, or MHC class II knockout APC were tested for their ability to exhibit prolonged DTH reactivity after infection with NU-2 (Fig. 5). At 16 days of infection, naïve mice were unresponsive when skin-tested with cryptococcal CneF skin test antigen. Immunization with both GXM-APC prepared with wild-type APC and with APC obtained from class I knockout mice was effective in allowing the mice to maintain their DTH response at the 16th day of infection. However, when the APC were obtained from class II knockout mice, the DTH response was no different than that observed in the infected mice that were not immunized (naïve group) prior to infection.

Figure 5.

Role of MHC class I and MHC class II in prolonging DTH responses in GXM-APC-immunized mice. Sham-infected mice were not immunized and were treated with PBS intratracheally at the time that other groups were infected. Naïve mice were not immunized but were infected. Immunized and infected mice were treated with GXM-APC obtained from wild-type (WT) mice, MHC class I deficient (Class I) or MHC class II deficient (class II) mice. Mice were skin tested with cryptococcal CneF 16 days after infection. Data are means ± standard errors of the means for eight individual C57Bl/6J mice per group.

Discussion

Previous investigations from our laboratory revealed that mice infected with a highly virulent isolate of C. neoformans initially respond to their infection but very shortly thereafter become unresponsive.1,20 These mice remain unresponsive until they die from their infection. During the responsive phase the mice exhibit DTH reactions to cryptococcal skin test antigen and their spleen cells secrete IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-10 when stimulated in culture with cryptococcal antigen. During the unresponsive phase, DTH responses are negative and antigen-stimulated spleen cells do not produce type 1 (IL-2, IFN-γ) or type 2 (IL-4, IL-10) cytokines.1 GXM-specific, CD8+ regulatory T cells are found in the spleens of mice during the unresponsive phase.3,21 Inhibition of the GXM-specific regulatory T-cell response is achieved by immunization of mice with activated APC pulsed ex vivo with small amounts of GXM.8 This immunization procedure induces a response that is GXM-specific (i.e. levan-APC does not inhibit the regulatory T-cell response induced by soluble GXM). GXM-APC immunized mice, challenged with viable NU-2, exhibit prolonged survival and a prolonged period of DTH reactivity when compared to naïve mice or mice immunized with APC that are not pulsed with GXM.8

The effects of GXM-APC immunization on cytokine and DTH responses of infected mice can be attributed to two separate activities.9 A GXM-independent response increases the type 1 cytokine responses that occur in response to a subsequent cryptococcal infection. This response does not develop unless the APCs used for immunization are activated.9 A GXM-specific response is induced that is responsible for prolonging survival and DTH reactivity of infected mice. Both of these responses are independent of IL-12 secretion by the infused APC and induction of an early IL-12 response in the GXM-APC-immunized mice.9

Co-stimulatory molecules found on the membranes of APC are important for the induction of T-cell responses.22–25 Included among these molecules are B7-1, B7-2 and CD40. In the current investigation, the contribution of these co-stimulatory molecules to the GXM-independent and GXM-specific immunomodulatory activities provided by the GXM-APC immunization was evaluated. The experimental model used in our investigation provided a mechanism to dissect the role of APCs used for immunization from APC function that is required for the host to respond to cryptococcal infection. This was achieved by using wild-type recipient animals that were immunized with GXM-APC prepared with wild-type APCs or APCs derived from knockout mice that did not express co-stimulatory molecules of interest. When knockout mice were not available, recipients were treated with antibodies that blocked the receptors under study during the induction phase of the anti-GXM response. These antibodies were cleared from the mice prior to infection so that they did not interfere with the immune response that developed after infection. Therefore the results presented apply to the characteristics of responses induced by the vaccine and not to characteristics of the naïve host to cryptococcal infection.

Initial experiments evaluated the contribution of CD40 to the efficacy of the GXM-APC. APC obtained from CD40 knockout mice were as effective as APCs harvested from wild-type mice for providing the non-specific immunomodulatory activity of GXM-APC treatment. These results revealed that expression of CD40 by the APC was not required for the immunopotentiating properties of GXM-APC.

To evaluate the role of the co-stimulatory molecules B7-1 and B7-2, recipient mice were treated 1 hr before immunization with GXM-APC and on the 3rd and 6th days after immunization with anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, or with both antibodies. While treatment with each of these antibodies alone decreased the subsequent infection-induced Th1 response, this inhibition was not statistically significant. However, mice that received the combined treatment with anti-B7-1 and anti-B7-2 over the first week after immunization had a significant reduction of their infection-induced Th1 response. It is important to note that anti-B7 treatment did not completely eliminate the Th1 response. The decrease was approximately 40% of that found in rat IgG-treated, GXM-APC-immunized mice. These results suggest that stimulation by B7 is not the only APC signal that contributes to the non-specific immunomodulatory effects of GXM-APC. Recently, additional molecules in the B7 family have been described.26 These molecules may also play a role in the immunomodulatory activity of the activated APC used in this investigation.

Treatment of mice with anti-B7 antibodies during the immunization period did not influence DTH reactivity in GXM-APC-immunized mice. This result provided evidence that the GXM-specific response induced by GXM-APC did not utilize B7-derived co-stimulatory signals. While it might be predicted that the decreased IFN-γ levels observed in this study might influence the level of DTH reactivity that developed in the mice, the anti-B7-treated mice did secrete significant amounts of IFN-γ which were apparently sufficient to support the development of the DTH response.

Kanoh et al.27 recently proposed that naïve T cells are influenced in an antigen-independent manner by cytokines secreted by APC such that committed precursor frequencies of T-cell subsets are altered. A shift similar to that described by Kanoh et al. could be responsible for the antigen-independent effects of the GXM-APC immunization. The antigen-independent stimulation in the studies reported here could be because of the combined stimulation of T cells with APC-derived cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules, such as B7 and others. Supporting this view are published observations that T cells can be stimulated directly through ligation of CD28 and/or CD5.27,28 We recently found that spleen cells harvested from mice 5 days after immunization with GXM-APC or untreated APC constitutively secrete high levels of type-1 cytokines, especially IFN-γ. The response was antigen-independent and occurred before infection of the mice with NU-2. Preliminary results show that CD4+ T cells in the spleens of GXM-APC- or APC-immunized mice are activated within 1 day following injection of GXM-APC or APC. These results suggest that APC-derived signals produced early after immunization may influence naïve T-cell differentiation toward the Th1 phenotype. An event such as this may account for the increased Th1 cytokine response that occurs upon infection of immunized mice with NU-2. The role that IFN-γ plays in the induction of the GXM-specific effects of GXM-APC immunization is currently under investigation.

The role that MHC expression plays in the induction of the GXM-independent and GXM-dependent responses induced by GXM-APC immunization was also evaluated. Knockout mice, deficient in their expression of MHC class I or MHC class II molecules, were used as the source of APC for the preparation of GXM-APC. In these experiments the non-specific immunomodulatory activity was found to be independent of the expression of MHC class I or MHC class II molecules on membranes of APC used in the vaccine. These results suggest that the non-specific immunomodulatory effects of the vaccine were not because of a direct stimulation of T cells by MHC molecules.

The GXM-specific response was dependent upon the expression of MHC class II antigens on the surface of the APC and was independent of the expression of MHC class I. The role for MHC II in this system is speculative as there is currently no information regarding the way that polysaccharide antigens are presented to the immune system. Polysaccharides do not stimulate T helper cell responses because they are not processed and presented by MHC. However, CD8+ regulatory T-cell responses specific for pure polysaccharide antigens have been described in our model of cryptococcosis and in other experimental systems.2,3,29 Therefore, in our system antigenic recognition of GXM may occur after binding of polysaccharide to the surface of the APC without a need for internalization or processing by the APC. The APC-bound polysaccharide may then be capable of directly interacting with T-cell receptors. GXM is known to bind to CD18 providing at least one mechanism whereby it could absorb to the surface of APC membranes.30

The role that MHC class II molecules play in this system is not known. We speculate that MHC class II may provide an additional signal to regulatory T cells that is different from those that are known for induction of T helper cell responses to protein antigens. In our own experience, GXM-specific CD8+ regulatory T cells are activated by GXM associated with APCs that are not activated.31 This reaction is inhibited with anti-I-E but not anti-I-A revealing a need for I-E in the triggering event. Consequently, we were not surprised to find that MHC molecules were needed for the counter-regulatory response induced by GXM-APC. This finding suggested that I-E is needed for the cellular interactions involved in the recognition event. In this context, I-E may not function for antigen presentation. From the experiments reported here, we are unable to determine if I-A or I-E molecules are responsible as the APCs used for preparation of GXM-APC were devoid of all class II molecules.

The Th1 response in cryptococcosis is induced by the protein-containing molecules of the organism.6 Since GXM contains no protein,6 it does not induce or elicit a DTH reaction (unpublished observations). However, the GXM-specific regulatory T-cell response indirectly influences DTH reactions by activating macrophages and T cells to release immunosuppressive mediators that inhibit DTH reactions in an antigen non-specific manner.5 The effects of GXM-APC immunization on DTH reactivity could be the result of induction of counter-regulatory T cells that inhibit the regulatory T-cell response. Future investigations will attempt to determine if counter-regulatory cells are responsible for inhibiting GXM-induced immunosuppression during NU-2 infection.

Immunization with GXM-APC provides a means to understand the mechanism used to inhibit one of the several immunosuppressive consequences of exposure to soluble GXM.32 The elucidation of these mechanisms can then be used in the future to design better vaccines and immunotherapies for cryptococcal infection. Vaccines and immunotherapies for this disease may ultimately need to incorporate several different strategies designed to enhance immune responses to protein-containing antigens of the organism while inhibiting the immunosuppressive consequences of the capsular polysaccharide.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-43325 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This work could not have been completed without the skilled technical services of Eric Neller and Tammy Windeknecht.

References

- 1.Blackstock R, Buchanan KL, Adesina AM, Murphy JW. Differential regulation of immune responses by highly and weakly virulent Cryptococcus neoformans isolates. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3601–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3601-3609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blackstock R, McCormack JM, Hall NK. Induction of a macrophage suppressive lymphokine by soluble cryptococcal antigens and its association with models of immunological tolerance. Infect Immun. 1987;55:233–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.233-239.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackstock R, Hernandez NC. Inhibition of phagocytosis in cryptococcosis: Phenotypic analysis of the suppressor cell. Cell Immunol. 1988;114:174–87. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackstock R, Hall NK, Hernandez NC. Characterization of a suppressor factor that regulates phagocytosis by macrophages in murine cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1773–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.6.1773-1779.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackstock R, Zembala M, Asherson GL. Functional equivalence of cryptococcal and haptene-specific T-suppressor factor (TsF) 2. Monoclonal anti-cryptococcal TsF inhibits both phagocytosis by a subset of macrophages and transfer of contact sensitivity. Cell Immunol. 1991;136:448–61. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90366-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy JW, Mosley RL, Cherniak R, Reyes G, Kozel TR, Reiss E. Serological, electrophoretic, and biological properties of Cryptococcus neoformans antigens. Infect Immun. 1988;56:424–31. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.424-431.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy JW, Schafer F, Casadevall A, Adesina A. Antigen-induced protective and nonprotective cell-mediated immune components against Cryptococcus neformans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2632–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2632-2639.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackstock R, Casadevall A. Presentation of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide (GXM) on activated antigen presenting cells inhibits the T-suppressor response and enhances delayed-type hypersensitivity and survival. Immunology. 1997;92:334–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackstock R, McElwee N, Neller E, Shaddix-White J. Regulation of cytokine expression in mice immunized with cryptococcal polysaccharide, a glucuronoxylomannan (GXM), associated with peritoneal antigen-presenting cells (APC): requirements for GXM, APC activation, and IL-12. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5146–53. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.5146-5153.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackstock R, Zembala M, Asherson GL. Functional equivalence of cryptococcal and haptene-specific T-suppressor factor (TsF) 1. Picryl and oxazolone-specific TsF, which inhibit transfer of contact sensitivity, also inhibit phagocytosis by a subset of macrophages. Cell Immunol. 1991;136:435–47. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(91)90365-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchanan KL, Murphy JW. Characterization of cellular infiltrates and cytokine production during the expression phase of the anticryptococcal delayed-type hypersensitivity response. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2854–65. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.2854-2865.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowak TP, Barondes SH. Agglutinin from Limulus polyphemus. Purification with formalinized horse erythrocytes as the affinity adsorbent. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;393:115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackstock R, Murphy JW. Secretion of the C3 component of complement by peritoneal cells cultured with encapsulated Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4114–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.10.4114-4121.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalckar HM. Differential spectrophotometry of purine compounds by means of specific enzymes III. Studies of the enzymes of purine metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1947;167:461–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaussabel D, Jacobs F, De Jonge J, De Veerman M, Carlier Y, Thielemans K, Goldman M, Vray B. CD40 ligation prevents Trypanosoma cruzi infection through interleukin-12 upregulation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1929–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1929-1934.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitmire JD, Flavell RA, Grewal IS, Larsen CP, Pearson TC, Ahmed R. CD40–CD40 ligand costimulation is required for generating antiviral CD4 T cell responses but is dispensable for CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 1999;163:3194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marriott I, Thomas EK, Bost KL. CD40–CD40L interactions augment survival of normal mice, but not CD40 knockout mice, challenged orally with Salmonella dublin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5253–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5253-5257.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linsley PS, Ledbetter JA. The role of the CD28 receptor during T-cell responses to antigen. Annu Rev Immunol. 1993;11:191–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson BE, Hall NK, Bulmer GS, Blackstock R. Suppression of responses to cryptococcal antigen in cryptococcosis. Mycopathology. 1982;80:157–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00437578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan MA, Blackstock R, Bulmer GS, Hall NK. Modification of macrophage phagocytosis in murine cryptococcosis. Infect Immun. 1983;40:493–500. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.2.493-500.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JG, Jenkins MK. Accessory cell-derived signals required for T-cell activation. Immunol Res. 1993;12:48–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02918368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweitzer AN, Borriello F, Wong RC, Abbas AK, Sharpe AH. Role of costimulators in T cell differentiation: studies using antigen-presenting cells lacking expression of CD80 or CD86. J Immunol. 1997;158:2713–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett SRM, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JFAP, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–80. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grewal IS, Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapoval AI, Ni J, Lau JS, et al. B7–H3: a costimulatory molecule for T cell activation and IFN-gamma production. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:269–74. doi: 10.1038/85339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanoh M, Uetani T, Sakan H, Maruyama S, Liu F, Sumita K, Asano Y. A two-step model of T cell subset commitment: antigen-independent commitment of T cells before encountering nominal antigen during pathogenic infections. Int Immunol. 2002;14:567–75. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandenberghe P, Verwilghen J, Van Vaeck F, Ceuppens JL. Ligation of the CD5 or CD28 molecules on resting human T cells induces expression of the early activation antigen CD69 by a calcium- and tyrosine kinase-dependent mechanism. Immunology. 1993;78:210–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Braley-Mullen H. Distinct populations of antigen-presenting cells are required for activation of suppressor and contrasuppressor T-cells by type-III pneumococcal polysaccharide. Cell Immunol. 1990;128:528–41. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90046-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dong ZM, Murphy JW. Cryptococcal polysaccharides bind to CD18 on human neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1997;65:557–63. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.557-563.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackstock R. Cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide utilizes an antigen-presenting cell to induce a T-suppressor cell to secrete TsF. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;34:19–30. doi: 10.1080/02681219680000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy JW. Cell-Mediated Immunity. In: Howard DH, Miller JD, editors. The Mycota, Animal and Human Relationships. VII. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1996. pp. 67–97. [Google Scholar]