Abstract

Dendritic cells (DC) are able to induce not only T helper 1 (Th1) but also Th2 immune responses after stimulation with allergens. While DC-derived interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-18 are the key factors for the induction of Th1 cells, early signals being involved in Th2 differentiation are less well characterized so far. To analyse such early signals we used an antigen-specific setting with CD4+ T cells from atopic donors stimulated in the presence of autologous mature DC, which were pulsed with different allergen doses. The addition of increasing amounts of allergen during DC maturation with tumour necrosis factor-α, IL-1β and prostaglandin E2 resulted in enhanced secretion of IL-6 and IL-12 by DC followed by increased production of Th1 (interferon-γ; IFN-γ) as well as Th2 (IL-4, IL-5) cytokines by CD4+ T cells. The coculture of allergen-treated DC and CD4+ T cells also led to a dose-dependent expression of active signal transducer and activator of transcription-6 (STAT6), which was visible already after 1 hr. Additionally, rapid phosphorylation of STAT6 was seen in immature DC after stimulation with allergens but not with lipopolysaccharide or human serum albumin. STAT6 phosphorylation was associated with the production of IL-13 by DC. The addition of neutralizing anti-IL-13 antibodies during maturation of DC inhibited STAT6 phosphorylation in CD4+ T cells as well as the production of IL-4, and to a lesser extent of IL-5, while IFN-γ production was not affected. Addition of exogenous IL-13 enhanced mainly the secretion of IL-4. Taken together, DC-derived IL-13, which is released after exposure to allergens appears to be one of the critical factors for DC to acquire the capability to induce Th2 cytokine production.

Introduction

Atopic/allergic immune responses are characterized by the presence of T helper 2 (Th2)-type cytokines released by allergen specific CD4+ T helper cells.1,2 During T helper cell differentiation distinct sets of transcription factors are expressed and activated. Cytokine dependent Th1/Th2 development leads to the activation of the Janus kinase family of receptor associated protein tyrosine kinases (JAK1-3, Tyk2). When activated, these kinases phosphorylate transcription factors of the signal transducer and activator of transcription family (STAT1-−5A, 5B−6). After phosphorylation the STAT molecules dimerize and translocate into the nucleus where they are necessary for the expression of cytokine genes.3,4 Whereas STAT4 is activated by interleukin (IL)-12 or interferon-α (IFN-α) and induces a Th1 differentiation, STAT6 has been shown to be important for Th2 development.5–7 The dependence of Th2 development on STAT6 has been demonstrated in developing Th1 cells transfected with an inducible STAT6 construct. Although committed towards a Th1 response these cells secreted type 2 cytokines after activation of STAT6.8 Conversely, STAT6 knock-out mice are deficient in IL-4-mediated Th2 cell differentiation and immunoglobulin E (IgE) class switching.9

Although many of the mechanisms and molecules relevant for T-helper differentiation have been investigated, the factors that initiate the first steps of this differentiation are less clear. Besides a genetic predisposition for allergic diseases and environmental factors like the presence of adjuvants, the mode of antigen/allergen contact seems to determine the ensuing immune response. In this respect, the frequency of encounter and the amount of allergen concentration are important factors. It has been demonstrated, that contact with low allergen concentrations induces predominantly Th2 responses, whereas higher concentrations induce Th1 cytokines.10,11 In addition, structural features of the allergen protein itself may have some influence on the immune response. Site-directed mutagenesis of house dust mite allergen lead to a complete shift from Th2 responses induced by the native protein towards IFN-γ production by the mutated protein.12 Furthermore, the route of allergen entry is among the main factors that influence the type of an immune response, partially caused by different types of antigen-presenting cells (APC) involved in T-helper cell stimulation.10,13,14 B cells are capable of inducing allergen-specific Th2 cells, whereas myeloid dendritic cells (DC) were initially thought to activate predominantly Th1 cells.15,16 Later, we and others have demonstrated that monocyte-derived DC cultured in vitro are able to induce Th1 as well as Th2 responses.17–20 While the induction of Th1 responses by DC can be explained by their production of IL-12 and IL-18,15,21 the knowledge of similar factors produced by DC (or other APC) to drive the T helper response towards Th2 are lacking. In this report, we demonstrate that monocyte-derived DC produce IL-13 after stimulation with allergens and elaborate the importance of this mediator for the induction of allergen-specific Th2 cells. APC-derived IL-13, which is produced only after distinct stimuli like allergens, appears to be one of the mediators that drive Th2 differentiation of T cells.

Materials and methods

Blood donors

Venous heparinized blood- or leukocyte-enriched buffy coats (Transfusion Centre, Mainz, Germany) from atopic donors suffering from allergic rhino-conjunctivitis or asthma to grass pollen, birch pollen, rye pollen and/or house dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus) was collected. Specific sensitization was documented by positive skin prick test to the respective allergen and detection of allergen-specific IgE in the sera (radioallergosorbent assay class ≥ 2).

Generation of monocyte-derived immature and mature DC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque 1·077 (Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany) density gradient centrifugation and 1 × 107 cells per well were incubated for 45 min in a six-well-plate (Costar, Bodenheim, Germany) in RPMI-1640 (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 3% autologous plasma at 37°. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing gently three times with warm phopshate-buffered saline (PBS). The remaining monocytes (purity > 90% CD14+) were incubated in 3 ml/well Iscove's modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM, Gibco BRL) supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated autologous plasma, 1000 U/ml IL-4 (Strathmann Biotech GmbH, Hannover, Germany) and 800 U/ml granulocye–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; Leucomax®, Sandoz AG, Nürnberg, Germany). Every other day 1 ml medium was replaced. On day 6 the resulting immature DC were either harvested for biochemical analysis and enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISpot) or pulsed with 0·1 or 10 µg/ml of grass pollen, birch pollen, rye pollen or house dust mite allergen extracts (ALK-Scherax, Hamburg, Germany). For some experiments, immature DC were treated with 5 µg/ml of a neutralizing anti-IL-13 or 1 µg/ml of a neutralizing anti-IL-4 antibody (R & D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). DC were matured by addition of 1000 U/ml tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), 2000 U/ml IL-1β (Strathmann Biotech GmbH) and 1 µg/ml prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Minprostin® E2, Pharmacia & Upjohn GmbH, Erlangen, Germany). Mature DC were harvested 48 hr after stimulation (the yield of DC out of 1 × 107 PBMC was 0·5–1 × 106 DC, purity > 95% (CD2/14/19 staining < 5%)), washed twice and used for T-cell stimulation assays.

Analysis of surface marker expression by flow cytometry

Surface phenotyping of DC was performed by staining 5 × 104 cells with specific mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for 20 min on ice. Antibodies used were CD80 (MAB104, Immunotech, Hamburg, Germany), CD83 (HB15a, Immunotech), CD86 (BU63, Camon, Wiesbaden, Germany) and rat anti-human HLA-DR (YE2/36HLK, Camon). After washing with PBS containing 0·1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) the cells were stained with PE-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) and fluorescein (DTAF)-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Dianova). After 20 min the cells were washed and analysed in a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA) equipped with CellQuest Software.

Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) assay

Endotoxin content of allergen extracts was tested with QCL-1000 chromogenic LAL (Bio-Whittaker, Walkersville, MD) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. For some experiments, 10 µg/ml polymyxin B sulphate (PMB, Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) was also added to the DC culture.22

Purification of CD4+ T cells and coculture with allergen-pulsed DC

Seven days after starting DC culture, autologous T cells were generated form cryoconserved PBMC of the same atopic donor. T cells were enriched using nylon wool columns as described.23 Briefly, nylon wool columns (0·6 g nylon wool/column) were preincubated with 10 ml of RPMI/3% autologous plasma for 30 min at 37°. 2–10 × 107 PBMC were loaded onto columns and incubated for 45 min at 37°. Non-adherent T cells were eluted from the column with 15 ml RPMI/3% plasma and incubated for 30 min on ice with mouse anti-human CD8 (OKT8 supernatant, American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD). CD8+ T cells were removed by depletion with anti-mouse IgG immunomagnetic Dynabeads (Dynal, Hamburg, Germany). Separation of isolated CD4+ T cells was controled by flow cytometry (purity > 90%).

For biochemical analysis, 5 × 106 CD4+ T cells were cocultured with 5 × 105 allergen-pulsed mature DC in six-well plates in 3 ml IMDM. After 1–6 hr, cocultured cells were harvested and DC were depleted using a mouse anti-human CD86 antibody (Camon) and anti-mouse Dynabeads (Dynal). During these steps cells were strictly kept on ice to prevent the induction of signal transduction by this procedure. Allergen-stimulated T cells were then lysed and analysed biochemically as described below.

For measurement of T cell cytokines, 5 × 105 CD4+ T cells were cocultured with 5 × 104 DC in 48-well plates in 1 ml IMDM/5% plasma. For some experiments, 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13 antibody or 5 ng/ml recombinant IL-13 (R & D Systems) was added from the beginning to the coculture. As the cytokine production of the T cells was rather weak after primary stimulation, we performed a secondary stimulation after 8 days. For this purpose, 5 × 104 freshly generated, fully matured DC from the same donor, optimally stimulated with 5 µg of allergen and in some experiments treated with 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13 antibody (R & D Systems) were added to the cocultures. Twenty-four hr after secondary stimulation, supernatant was collected and analysed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Measurement of cytokines by ELISA

Human IL-4, IL-5, IL-12p40, IFN-γ (BD Pharmingen) and IL-6 (R & D Systems) were measured by ELISA according to the instructions of the distributor as described previously.17 Detection limit was 8 pg/ml for IL-4, and 32 pg/ml for all other cytokines.

ELISpot assay for detection of IL-13 secretion by DC

For detection of IL-13 producing DC an ELISpot assay (R & D Systems) was employed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the anti-IL-13 coated polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane was blocked for 45 min at 37° with 200 µl IMDM/10% autologous plasma. Then, 5 × 104 immature DC were seeded into each well and stimulated with 0·1 or 10 µg/ml allergen extracts, 10 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/0·5 µg/ml ionomycin (Sigma), 2·4 µg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA; Biochrom KG) or 100 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma). After incubation for 48 hr, the plates were washed and incubated with a biotinylated detection antibody at 4° overnight. The next day, streptavidin AP was added to each well and removed after 2 hr at room temperature. Then, the chromogen substrate BCIP/NBT was added and spot development was visible within 30 min. To elevate spot numbers, the KS ELISPOT imaging system (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) was employed.

Preparation of cell extracts

For analysis of immature DC, cells were harvested and washed thrice with PBS to remove cytokines completely. A total of 1·5 × 106 cells were resuspended in 500 µl IMDM (without cytokines or plasma) and preincubated at 37° for 60 min. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of allergen, LPS (10 ng/ml), a control protein (human serum albumin; HSA, 10 µg/ml), IL-4 (10 ng/ml), IL-13 (5 ng/ml) or mock stimulated with PBS for 15 min at 37°. DC were lysed in 50 µl ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7,4, 150 mm NaCl, 1·5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 10% glycerol, 1% Triton-X-100, 2 mm phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 µg/ml aprotinin and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate) by vigorous resuspension and incubation on ice for 30 min. Insoluble material was spun down (20 min, 15 000 g, 4°) and the clear supernatants were stored at −70°.

Protein content of the lysates was determined using the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacryalamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and Western Blot

Cell lysates (150 µg/lane) were mixed with loading buffer (Roti Load, 4× concentrated, Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) heated for 5 min at 96° and subjected to SDS–PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel with 0·5% SDS using standard procedures (45 mA, maximum 500 V). A biotinylated Mr-marker (Boehringer Mannheim) and a prestained Mw-marker (Boehringer Mannheim) were run in parallel for quantification of the Mw after Western transfer and for assessment of transfer efficiency, respectively. Proteins were blotted onto PVDF-membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA) using a semidry blotting unit (Trans-Blot SD, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) in a Tris/Glycin buffer for 50 min at 250 mA and a maximum of 25 V. After transfer, the membranes were blocked in blocking buffer (PBS containing 0·1% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat dry milk powder) for a minimum of 1 hr.

For detection the membranes were incubated with 2 µg of primary antibodies (antiphospho-STAT6 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) or anti-STAT6 polyclonal rabbit antisera (Santa Cruz)) for 2 hr and with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (NEB) at a dilution of 1 : 1000 in blocking buffer for 1 hr. Blots were developed using chemoluminescence (ECL system, Amersham International, Amersham, UK). Sequential detection of different antigens was achieved by incubating the membranes in stripping buffer (62·5 mm Tris/HCl, 2% SDS and 100 mm 2-mercaptoethanol (ME), pH 6,7) for 45 min at 50° and washing in TBS + Tween-20 to remove antibodies before further analysis.

Statistics

Student's t-test was employed to test the statistical significance of the results; P ≤ 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Dendritic cells matured in the presence of increasing amounts of allergen secrete increasing amounts of IL-6 and IL-12

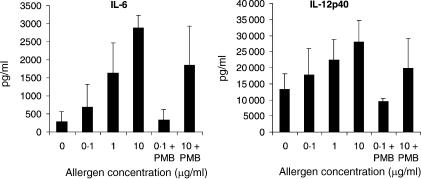

To investigate the influence of allergens on DC phenotype and cytokine production, immature monocyte-derived DC from atopic donors were stimulated for 48 hr with IL-1β, TNF-α and PGE2 to achieve full maturation in the presence or absence with different concentrations of allergen. Flow cytometric analysis revealed, that the typical phenotype of fully matured DC characterized by high expression of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecule HLA-DR, the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, and the DC-specific marker CD83 was not affected by different allergen concentrations (data not shown). The addition of increasing concentrations of allergen during DC maturation led to an increased production of IL-6 and of the Th1-inducing cytokine IL-12p40 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Increased amounts of allergen induce increased levels of IL-6 and IL-12 production by DC. DC were generated from peripheral blood monocytes isolated from atopic donors. On day 6 of culture, immature DC were pulsed with different allergen doses as indicated and stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α and PGE2 to induce full maturation. At the same time point, 10 µg/ml PMB was added to neutralize endotoxin contamination in the allergen preparations. Supernatants were harvested 48 h later and analysed for IL-6 and IL-12p40 content by ELISA. The results represent the means ± SD from four independent experiments.

To rule out any effects of endotoxin contamination of the allergen extracts on the cytokine release of DC, all allergen preparations used in this study were analysed for their endotoxin content by employing the highly sensitive LAL-Assay, and only batches with a contamination of endotoxin < 1 ng/ml were used. Furthermore, endotoxin was neutralized by the addition of the antibiotic PMB.22 Cytokine secretion after stimulation with different allergen concentrations was still measurable in a dose dependent manner even in the presence of PMB (Fig. 1).

Maturation of DC in the presence of allergens leads to the development of IFN-γ- and of IL-4-secreting T-helper cells

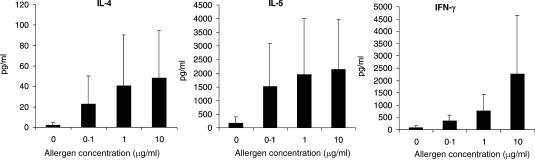

When allergen-treated, mature DC were used in coculture experiments with CD4+ T helper cells of the same allergic donor, these T cells were induced to secrete the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ as well as the Th2 cytokine IL-4 (Fig. 2). Increasing amounts of allergens added during the maturation of the APC led to increased allergen presentation and thereby to the secretion of increased amounts of T-cell cytokines. This increase of cytokine secretion did not depend on LPS contaminations of the allergen preparations, as neutralization of LPS did not affect cytokine secretion (data not shown).

Figure 2.

DC pulsed with increased amounts of allergen induce increased levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IFN-γ by CD4+ T helper cells. Five × 105 CD4+ T cells were cocultured with 5 × 104 autologous mature DC which were pulsed with different allergen doses in the presence or absence of PMB. After 8 days of culture, T cells were restimulated with 5 × 104 newly generated mature DC of the same donor which were pulsed with an optimal dose (5 µg/ml) of the respective allergen. Supernatants were harvested 24 hr later and analysed for IL-4 and IL-5 and IFN-γ content by ELISA. Shown are the means ± SD from 10 independent experiments.

Activation of transcription factor STAT6 in Th cells during coculture with allergen treated DC

The increased secretion of IFN-γ by CD4+ Th cells during coculture with allergen-pulsed DC may be due to the increased secretion of IL-12 by the allergen presenting DC. But the increased secretion of IL-4 with increased allergen concentrations presented by DC is much more difficult to explain. Therefore, we investigated the activation of transcription factor STAT6, an early signal transduction event induced in Th2 cells. Time course studies revealed the activation of this transcription factor in cell lysates of CD4+ T cells cultured together with allergen presenting DC as shown by Western blotting. Within 1 hr of coculture a slight protein band corresponding to active STAT6 was visible and increased during the following 6 hr, whereas the overall STAT6 expression remains unaffected (Fig. 3a). Twenty-four hr after start of the coculture the phospho-STAT6 signal decreased significantly (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Induction of the transcription factor STAT6 in CD4+ T helper cells after stimulation with allergen-pulsed DC. Five × 106 CD4+ T cells were cocultured with 5 × 105 autologous DC which were pulsed with different allergen doses in the presence or absence of PMB. DC were depleted after 1–6 hr (a) or 5 hr (b) of culture. Then, T cells were lysed and analysed for STAT6 expression by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods.

The amount of activated STAT6 was not only influenced by the duration of the coculture, but also by the strength of the initial interaction between allergen-specific T cells and allergen-presenting DC. This was seen in experiments, where DC pulsed with increasing amounts of allergen were used to activate autologous T helper cells (Fig. 3b). Again, the induction of Th2 driving STAT6 was in no way influenced by LPS contaminations of the allergen preparations used to initially pulse the DC, as the use of PMB did not affect STAT 6 activation in T cells.

STAT6 activation was not exclusively seen in cocultures of CD4+ T cells and allergen-pulsed DC from atopic donors but also in cocultures from nonatopic donors (data not shown).

Influence of allergen uptake on immature DC

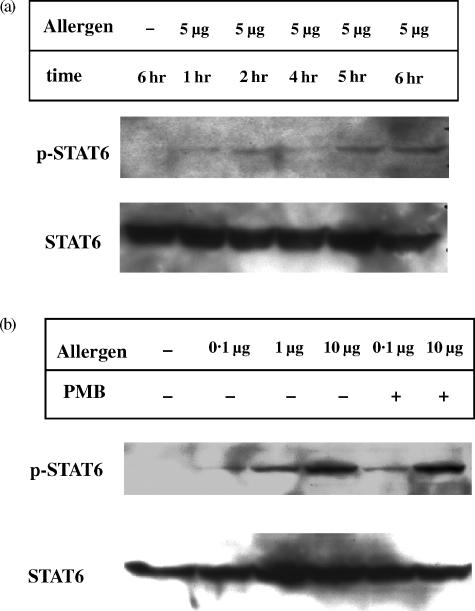

Allergen uptake by immature DC leads to the development of APC which are able to induce the production of Th1 cytokines as well as Th2 cytokines in autologous CD4+ T cells. To address the question whether allergen uptake of immature DC influences the development of potentially Th2 driving DC, we analysed the expression and activity of the Th2-associated transcription factor STAT6 also in these cells. All allergen-induced effects were compared to stimuli with no allergenic properties (LPS or HSA).

Time course studies revealed a rapid phosphorylation of STAT6 in immature DC from atopic or nonatopic donors after stimulation with allergens but not with LPS (Fig. 4a) or HSA (data not shown). Phospho-STAT6 appeared with a peak 5–15 min after stimulation and decreased after 30 min (Fig. 4a). Furthermore, increased amounts of allergens induced increased STAT6 activation as seen in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Induction of the transcription factor STAT6 in immature DC after stimulation with increasing amounts of allergen. On day 6 of culture, 1·5 × 106 immature DC were preincubated at 37° for 60 min before treatment with different allergen doses or 10 ng/ml LPS. After 5–60 min DC were lysed and analysed for STAT6 expression by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods.

Production of IL-13 by immature and mature allergen-pulsed DC and IL-13 responsiveness by DC

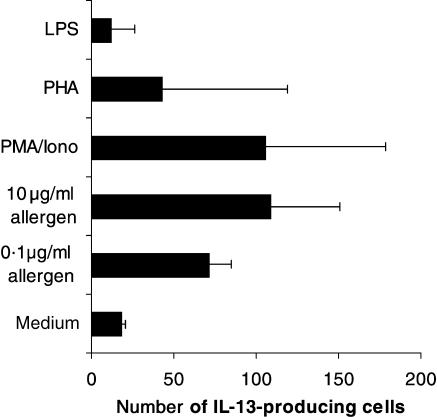

The addition of increasing amounts of allergen to immature monocyte-derived DC not only induced the activation of transcription factor STAT6, but also the production of IL-13 as detected by ELISpot. Allergen concentrations of 10 µg/ml were able to induce similar IL-13 spot counts as the known inductor of IL-13 in DC, PMA/ionomycin.24 Again, LPS had no effect on the number of IL-13-secreting DC (Fig. 5) and immature DC from non-atopic donors were also able to produce IL-13 (data not shown). When mature DC were analysed for IL-13 production, the number of spots induced by the cytokine cocktail used for DC-maturation were so high (up to 200 spots/50 000 mature DC) that no additional allergen-induced IL-13 production could be found (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Immature DC produce IL-13 after stimulation with increasing amounts of allergen. On day 6 of culture, 5 × 104 immature DC were seeded on an anti-IL-13 coated PVDF membrane and stimulated with 0·1–1 µg/ml allergen extract, 10 ng/ml PMA/0·5 µg/ml ionomycin, 2·4 µg/ml PHA or 100 ng/ml LPS. After 48 h the ELISpot assay was continued as described in Materials and Methods. The results represent the means ± SD of the number of IL-13 producing cells from three independent experiments.

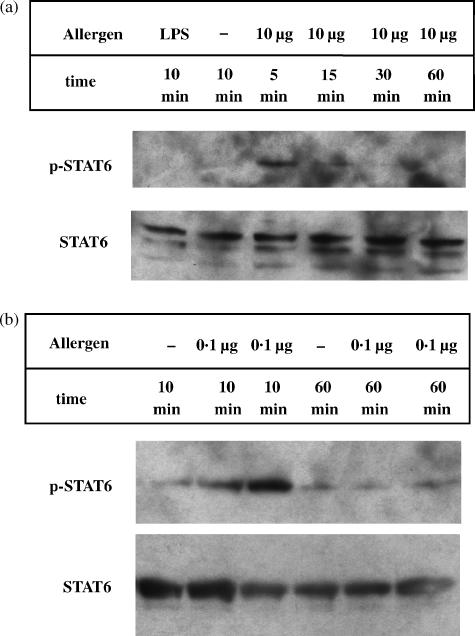

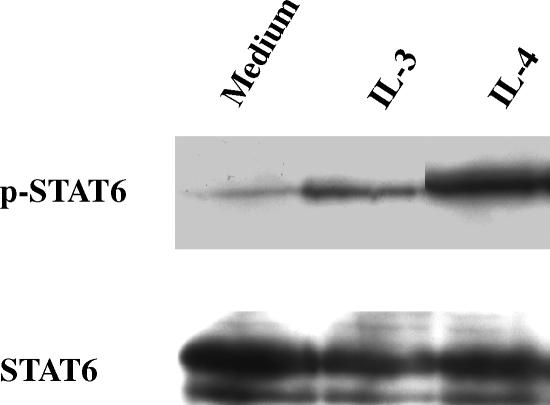

Besides the production of IL-13 by DC, we also analysed the IL-13 responsiveness of DC. In Fig. 6 is shown that DC respond to IL-13 as we detected a signal for phosphorylated STAT6 after stimulation of immature DC with IL-13, which was almost as strong as the signal obtained using IL-4 as stimulus.

Figure 6.

IL-13 responsiveness of immature dendritic cells. On day 6 of culture, 1·5 × 106 immature DC were preincubated at 37° for 60 min before treatment with 10 ng/ml IL-4 or 5 ng/ml IL-13. After 10 min DC were lysed and analysed for STAT6 expression by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods.

Functional role of IL-13 for DC function and Th2-development

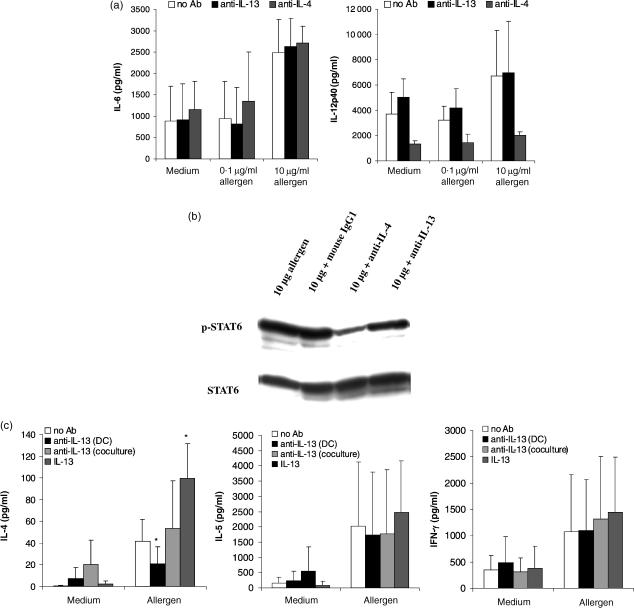

To investigate the functional role of IL-13 produced by DC, an IL-13 neutralizing antibodies was added together with allergen and cytokine cocktail during DC maturation. DC matured in the presence or absence of anti-IL-13 did not differ morphologically and did express equal densities of the cell surface markers CD83 and CD86 (data not shown).

Additionally, neutralization of IL-13 had no effect on the secretion of the DC cytokines IL-6 and IL-12 (Fig. 7a). In contrast, when neutralizing anti-IL-4 antibodies were used as a control for antibody treatment of DC, the production of IL-12 by these cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 7a), underlining the importance of IL-4 for the regulation of IL-12 production by DC.25

Figure 7.

Neutralization of IL-13 has no effect on DC cytokine production, but reduces the potency to induce production of the Th2 cytokine IL-4 by T cells. (a) On day 6, immature DC were pulsed with different allergen doses as indicated and stimulated with IL-1β, TNF-α and PGE2 with or without the addition of 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13 or 1 µg/ml anti-IL-4 mAbs. Supernatants were harvested 48 hr later and analysed for IL-6 and IL-12p40 content by ELISA. The results represent the means ± SD from four independent experiments. (b) 5 × 106 CD4+ T cells were cocultured with 5 × 105 autologous mature DC which were pulsed with 10 µg/ml allergen ± 1 µg/ml anti-IL-4, 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13, or 5 µg/ml mouse IgG1 isotype control. DC were depleted after 5 hr of culture. Then, T cells were lysed and analysed for STAT6 expression by Western blot as described in Materials and Methods. (c) CD4+ T cells (5 × 105) were cocultured with 5 × 104 autologous mature DC which were pulsed with 0·1–10 µg/ml allergen ± 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13 mAbs. After 8 days of culture, which was additionally performed ± 5 µg/ml anti-IL-13 mAbs or 5 ng/ml recombinant IL-13, T cells were restimulated with 5 × 104 newly generated DC of the same donor which were pulsed with an optimal dose (5 µg/ml) of the respective allergen. Supernatants were harvested 24 hr later and analysed for IL-4, IL-5 and IFN-γ content by ELISA. Shown are the means ± SD of six (for IL-4) and 10 (for IL-5 and IFN-γ) independent experiments. *indicates statistically significant differences (P ≤ 0·05) between absence or presence of anti-IL-13 or -IL-13.

A strong effect of IL-13 neutralization was seen when the activation of allergen-specific CD4+ T-helper cells by allergen-presenting DC was assessed. For these experiments, DC matured in the presence of allergen and neutralizing anti-IL-13 antibodies were used for cocultures with autologous CD4+ Th cells. First, STAT6 phosphorylation was decreased under these conditions, but the inhibition was not so strong as being observed after the addition of neutralizing anti-IL-4 antibodies during DC maturation. The use of isotype control antibodies had no effect on STAT6 activation (Fig. 7b). The allergen-induced secretion of the Th2 cytokine IL-4 was also significantly reduced, when DC-derived IL-13 was blocked especially at low allergen concentrations (Fig. 7c), while isotype control antibodies did not inhibit IL-4 production (data not shown). Conversely, the addition of IL-13 to the cocultures lead to a three-fold increase of IL-4 secretion compared to T cells stimulated by allergen pulsed DC without additional IL-13 (Fig. 7c). Interestingly, the addition of anti-IL-13 antibodies at a later time point, i.e. at the start of the cocultures had no inhibiting effect, but lead to a slight increse in IL-4 secretion. This may be due to non-specific T cell activation by the antibody molecule itself. The effect of IL-13 appeared to be restricted to the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and to a lesser extent IL-5, as the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was not affected by neutralization of IL-13 at any time (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

Fully matured monocyte-derived DC are known to be strong inducers of Th1-dominated immune responses. This might be partly caused by the secretion of the Th1-inducing cytokines IL-12 and IL-18·21,26,27 For this reason monocyte-derived DC have also been referred to as IFN-γ-inducing DC1.16 Previously, we have shown that DC of allergic donors, matured in the presence of allergen protein, are not only able to induce IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells, but also IL-4- and IL-5-secreting Th2 cells of the same donor.17 To investigate the factors, which make a DC an inducer of Th2 cytokines20 we now analysed the effect of allergen treatment on DC development and on T helper cell differentiation.

The active process of antigen uptake by immature DC via phagocytosis involves several cellular activation processes and leads in vivo to cell migration and maturation. When DC are generated under cell culture conditions and incubated with protein allergens, this stimulus alone is not sufficient to induce DC maturation, but a cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines is necessary to achieve full maturation.28,29 Nevertheless, allergen uptake has an influence on the resulting function of the DC. Whereas cell morphology and cell surface marker expression (at least as the markers investigated by us are concerned) are not influenced by allergen uptake, the DC secrete increasing amounts of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-12p40 with increasing concentrations of allergen, and bioactive IL-12p70 had also been detected by us in earlier experiments.17 This IL-12 production can account for the strong ability of monocyte-derived DC to induce IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells.27,30 Concerning our allergen-specific setting, we have already demonstrated that neutralization of IL-12 during the maturation phase of DC or during coculture of DC and CD4+ T cells diminished the production of IFN-γ but did not enhance the production of IL-4 and IL-5.17 Herein, we show that DC exposed to increasing amounts of allergens are also able to induce the secretion of increasing amounts of IL-4 by T cells of allergic donors at least in a certain dose range. This finding is in contrast to observations reporting that low antigen/allergen doses are more suitable for the induction of Th2 immune responses10,11,31 but may be explained by the mechanisms described below.

A well known early event during Th2 differentiation is the phosphorylation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription STAT6, its dimerization and translocation into the nucleus.5,6,8 When coculture experiments with allergen-pulsed DC and CD4+ T cells of the same allergic donor were investigated, STAT6 was activated in the T-cell population within 1 hr of coculture. We found an increase of STAT6 phosphorylation with the time of coculture but also with the allergen concentration used to initially pulse the DC. Thus, the stronger the interaction between allergen/peptide-loaded MHC class II molecules on DC surface and allergen/peptide-specific TCR, the more STAT6 phosphorylation occurs and the more IL-4 is released by the T cells. Similar results were obtained for activation of STAT4 in response to increasing allergen concentrations (data not shown), which correspond to the enhanced IL-12 production by DC depending on the amount of allergen leading to increased production of IFN-γ by T cells.

The ability of allergen-pulsed DC to induce Th2 cytokines in T helper cells may be in part a result of the intrinsic properties of the allergen itself. This is demonstrated by the fact, that only the uptake of protein allergens by immature DC induces the phosphorylation of STAT6 in this cell type itself. When proteins with no allergenic properties, like HSA, were used, no STAT6 phosphorylation was observed. In addition, even strong cellular activators like contact sensitizers are not able to induce a significant STAT6 phosphorylation or activation of other STATs in DC.32 However, DC and CD4+ T cells cocultured with allergen-pulsed DC from non-atopic donors also showed concentration-dependent STAT6 phosphorylation but without producing similar high amounts of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-517 implicating that additional factors apart from STAT6 are responsible for the induction of Th2 cytokine production.

The transcription factor STAT6 is known to be involved in the expression of IL-4. But as DC do not produce or secrete any IL-4, the connection between STAT6 phosphorylation in DC on the one hand and Th2 induction on the other hand cannot be explained by IL-4 effects. The cytokine IL-13 shows many structural and functional similarities to IL-4. The two cytokines have evolved by gene duplication, which explains their partial redundancy.33 Similar to IL-4, IL-13 is involved in allergic immune responses as IL-13 can induce IgE and IgG4 production by B cells, eosinophilia and airways hyper-reactivity (AHR) independently of IL-4 or the IL-4Rα chain complex.34–36 STAT6 signal transduction seems to be critical in the development of allergic airway responses as STAT6-deficient mice do not develop AHR.37 However, in contrast to IL-4, IL-13 fails to induce Th2 differentiation in naive CD4+ T cells indicating that these T cells do not express functional IL-13R38,39 whereas T cells from peripheral blood have been shown to signal in response to IL-13.40 Furthermore, IL-13 seems to be an important mediator of the effector phase of allergic immune responses.41 In how far the STAT6 phosphorylation and IL-13 production are connected in DC is the subject of further investigations. The data presented in the current investigation indicate at least that IL-13 plays also a critical role early in the initiation of Th2 responses, even it may not act directly on T cells, but rather on the DC themselves, which respond to IL-13 by up-regulating phospho-STAT6.

DC have previously been shown to express IL-13 mRNA and protein after stimulation with PMA/ionomycin.24 In the present report, we now demonstrate the secretion of IL-13 by immature monocyte-derived DC 48 hr after incubation with increasing concentrations of protein allergens. These results were obtained using a highly sensitive ELISpot technique. When DC were treated with allergen together with the maturation cocktail of pro-inflammatory cytokines, no allergen-dependent enhancement was seen as the number of IL-13 specific spots was already very high due to the maturation stimuli.

The functional relevance of IL-13 secreted by DC matured in the presence of allergens can be concluded from our experiments with a IL-13 neutralizing antibody. Regularly matured allergen presenting DC-induced IL-4-secreting T helper cells. In contrast, the pretreatment of DC with an anti-IL-13 antibody significantly reduced not only phosphorylation of STAT6 in CD4+ T cells, but also the Th2-inducing capacity of the DC. This effect was mainly seen for the production of IL-4 at low allergen concentrations and to a lesser extent for IL-5 by the allergen-specific T cells. At the same time, the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ was not affected by the neutralizing antibody. When anti-IL-13 was added directly to the coculture of DC and CD4+ T cells, no IL-4 inhibiting effect was seen, but even an increased secretion of IL-4 was measured. This result may be explained by non-specific activation of the cells by the antibody molecules. It also demonstrates that the importance of IL-13 for the induction of Th2 cells may rest in its early effect on immature DC rather than on mature DC or T cells. Addition of IL-13 leads to enhanced production of Th2 cytokines probably due to the down-regulation of Th1-inducing cytokines, particularly of IL-12.42,43 It could also be possible that IL-13 is additionally affecting T cells directly as it was shown by Yu et al. that addition of IL-13 to anti-CD3/IL-2- or PHA-stimulated T cells inhibits the production of IFN-γ.40 The anti-IL-13 treatment had no effect on cell surface expression of CD86 and CD83 or on the secretion of the DC cytokines IL-6 and IL-12, ruling out effects via the modulation of these molecules at least.

Taken together, the data indicate that the type of antigen is important for the signals elicited in DC (STAT6, IL-13), which may involve so far unknown physicochemical properties of allergens that render them allergenic (able to induce Th2 responses leading to IgE production). The data also indicate that STAT6 plays a pivotal role in the induction of Th2 responses not only in T cells, but also in DC. Last but not least, IL-13 may be one of the critical factors that lead to the induction of Th2 cytokine production, like IL-12 and IL-18 are important for Th1 cytokine induction. However, the fact that non-atopic donors also produce active STAT6 and IL-13 and that DC from atopic donors are not impaired in the production of bioactive IL-1217 implies that other factors are also involved in the induction of Th2 cytokine production. Nevertheless, our findings may have strong implications for the understanding of the immunopathology of Th2-mediated diseases, like atopic diseases, and may also lead to the development of new therapeutic interventions in these diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant SA 483/6-1. The first two authors contributed equally.

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cells

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- AHR

airways hyper-reactivity

- PMB

polymyxin B sulphate

References

- 1.van der Heijden FL, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, Kapsenberg ML. High frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+ allergen-specific T lymphocytes in atopic dermatitis lesional skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:389–94. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12480966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricci M, Rossi O, Bertoni M, Matucci A. The importance of Th2-like cells in the pathogenesis of airway allergic inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy. 1993;23:360–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu CR, Young HA, Ortaldo JR. Characterization of cytokine differential induction of STAT complexes in primary human T and NK cells. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:245–58. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heim MH. The Jak-STAT pathway: cytokine signalling from the receptor to the nucleus. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 1999;19:75–120. doi: 10.3109/10799899909036638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriggl R, Kristofic C, Kinzel B, Volarevic S, Groner B, Brinkmann V. Activation of STAT proteins and cytokine genes in human Th1 and Th2 cells generated in the absence of IL-12 and IL-4. J Immunol. 1998;160:3385–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christodoulopoulos P, Cameron L, Nakamura Y, et al. Th2 cytokine-associated transcription factors in atopic and nonatopic asthma: evidence for differential signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:586–91. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.114883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frucht DM, Aringer M, Galon J, et al. Stat4 is expressed in activated peripheral blood monocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages at sites of Th1-mediated inflammation. J Immunol. 2000;164:4659–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurata H, Lee HJ, O'Garra A, Arai N. Ectopic expression of activated Stat6 induces the expression of Th2-specific cytokines and transcription factors in developing Th1 cells. Immunity. 1999;11:677–88. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimoda K, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, et al. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–3. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Secrist H, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Interleukin 4 production by CD4+ T cells from allergic individuals is modulated by antigen concentration and antigen- presenting cell type. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1081–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosken NA, Shibuya K, Heath AW, Murphy KM, O'Garra A. The effect of antigen dose on CD4+ T helper cell phenotype development in a T cell receptor-alpha-beta-transgenic model. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1579–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korematsu S, Tanaka Y, Hosoi S, Koyanagi S, Yokota T, Mikami B, Minato N. C8/119S mutation of major mite allergen derf-2 leads to degenerate secondary structure and molecular polymerization and induces potent and exclusive Th1 cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2000;165:2895–902. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Lamm WJ, Albert RK, Chi EY, Henderson WR, jr, Lewis DB. Influence of the route of allergen administration and genetic background on the murine allergic pulmonary response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:661–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Constant SL, Lee KS, Bottomly K. Site of antigen delivery can influence T cell priming: pulmonary environment promotes preferential Th2-type differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:840–7. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<840::AID-IMMU840>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heufler C, Koch F, Stanzl U, et al. Interleukin-12 is produced by dendritic cells and mediates T helper 1 development as well as interferon-gamma production by T helper 1 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:659–68. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rissoan MC, Soumelis V, Kadowaki N, Grouard G, Briere F, de Waal Malefyt R, Liu YJ. Reciprocal control of T helper cell and dendritic cell differentiation. Science. 1999;283:1183–6. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5405.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellinghausen I, Brand U, Knop J, Saloga J. Comparison of allergen-stimulated dendritic cells from atopic and nonatopic donors dissecting their effect on autologous naive and memory T helper cells of such donors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:988–96. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.105526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Snijders A, Snijdewint FG, Kapsenberg ML. IL-12-deficient dendritic cells, generated in the presence of prostaglandin E2, promote type 2 cytokine production in maturing human naive T helper cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stumbles PA, Thomas JA, Pimm CL, Lee PT, Venaille TJ, Proksch S, Holt PG. Resting respiratory tract dendritic cells preferentially stimulate T helper cell type 2 (Th2) responses and require obligatory cytokine signals for induction of Th1 immunity. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2019–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambrecht BN. The dendritic cell in allergic airway diseases: a new player to the game. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:206–18. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoll S, Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Muller G, Yamauchi H, Kurimoto M, Knop J, Enk AH. Production of functional IL-18 by different subtypes of murine and human dendritic cells (DC): DC-derived IL-18 enhances IL-12- dependent Th1 development. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3231–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199810)28:10<3231::AID-IMMU3231>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs DM, Morrison DC. Inhibition of mitogenic response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in mouse spleen cells by polymyxin B. J Immunol. 1977;118:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julius MH, Simpson E, Herzenberg LA. A rapid method for the isolation of functional thymus-derived murine lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1973;3:645–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830031011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Saint Vis B, Fugier Vivier I, Massacrier C, et al. The cytokine profile expressed by human dendritic cells is dependent on cell subtype and mode of activation. J Immunol. 1998;160:1666–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalinski P, Smits HH, Schuitemaker JH, Vieira PL, van Eijk M, de Jong EC, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. IL-4 is a mediator of IL-12p70 induction by human Th2 cells: reversal of polarized Th2 phenotype by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:1877–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelsall BL, Stuber E, Neurath M, Strober W. Interleukin-12 production by dendritic cells. The role of CD40− CD40L interactions in Th1 T-cell responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;795:116–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and its role in the generation of TH1 cells. Immunol Today. 1993;14:335–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90230-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonuleit H, Kuhn U, Muller G, Steinbrink K, Paragnik L, Schmitt E, Knop J, Enk AH. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandins induce maturation of potent immunostimulatory dendritic cells under fetal calf serum-free conditions. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:3135–42. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shevach EM, Chang JT, Segal BM. The critical role of IL-12 and the IL-12R beta 2 subunit in the generation of pathogenic autoreactive Th1 cells. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:249–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00812256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers PR, Croft M. CD28, Ox-40, LFA-1, and CD4 modulation of Th1/Th2 differentiation is directly dependent on the dose of antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2955–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valk E, Zahn S, Knop J, Becker D. JAK/STAT pathways are not involved in the direct activation of antigen-presenting cells by contact sensitizers. Arch Dermatol Res. 2002;294:163–7. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0309-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chomarat P, Banchereau J. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13: their similarities and discrepancies. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;17:1–52. doi: 10.3109/08830189809084486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Punnonen J, Aversa G, Cocks BG, McKenzie AN, Menon S, Zurawski G, de Waal Malefyt R, de Vries JE. Interleukin 13 induces interleukin 4-independent IgG4 and IgE synthesis and CD23 expression by human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3730–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, et al. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282:2261–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattes J, Yang M, Siqueira A, et al. IL-13 induces airways hyperreactivity independently of the IL-4ralpha chain in the allergic lung. J Immunol. 2001;167:1683–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuperman D, Schofield B, Wills-Karp M, Grusby MJ. Signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 6 (Stat6)-deficient mice are protected from antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and mucus production. J Exp Med. 1998;187:939–48. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sornasse T, Larenas PV, Davis KA, de Vries JE, Yssel H. Differentiation and stability of T helper 1 and 2 cells derived from naive human neonatal CD4+ T cells, analysed at the single-cell level. J Exp Med. 1996;184:473–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Vries JE. The role of IL-13 and its receptor in allergy and inflammatory responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:165–9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu CR, Kirken RA, Malabarba MG, Young HA, Ortaldo JR. Differential regulation of the Janus kinase-STAT pathway and biologic function of IL-13 in primary human NK and T cells: a comparative study with IL-4. J Immunol. 1998;161:218–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–61. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Andrea A, Ma X, Aste-Amezaga M, Paganin C, Trinchieri G. Stimulatory and inhibitory effects of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 on the production of cytokines by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: priming for IL-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha production. J Exp Med. 1995;181:537–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wills-Karp M. IL-12/IL-13 axis in allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:9–18. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]