Abstract

Two independently segregating C9 genetic defects have previously been reported in two siblings in an Irish family with subtotal C9 deficiency. One defect would lead to an abnormal C9 protein, with replacement of a cysteine by a glycine (C98G). The second defect is a premature stop codon at amino acid 406 which would lead to a truncated C9. However, at least one of two abnormal proteins was present in the circulation of the proband at 0·2% of normal C9 concentration. In this study, the abnormal protein was shown to have a molecular weight approximately equal to that of normal C9, and to carry the binding site for monoclonal antibody (mAb) Mc42 which is known to react with an epitope at amino acid positions 412–426, distal to 406. Therefore, the subtotal C9 protein carries the C98G defect. The protein was incorporated into the terminal complement complex, and was active in haemolytic, bactericidal and lipopolysaccharide release assays. A quantitative haemolytic assay indicated even slightly greater haemolytic efficiency than normal C9. Epitope mapping with six antihuman C9 mAbs showed the abnormal protein to react to these antibodies in the same way as normal C9. However, none of these mAbs have epitopes within the lipoprotein receptor A module, where the C98G defect is located. The role of this region in C9 functionality is still unclear. In conclusion, we have shown that the lack of a cysteine led to the production of a protein present in the circulation at very much reduced levels, but which was fully functionally active.

Introduction

Complement component C9 is the final component incorporated into the membrane attack complex (MAC). After binding to the membrane-bound components C5b to C8 (C5b-8), the C9 molecules unfold and bind with each other to form a cylinder that becomes inserted into the target membrane.1 Unlike components C5b to C8, which occur only once in each individual MAC, the MAC may contain a variable number of nine or more C9 molecules. Monomers of C9 can also polymerize to form tubular polyC9.2 C9 participates in important functions of the MAC,3 including haemolysis, bacteriolysis4 and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) release.5 Nevertheless, there are reports that some MAC functional activities can sometimes be carried out in the presence of C5 to C8, but in the absence of C9.6 The C9 protein interacts with the C5-8 complex at the outer cell membrane;1 however, the precise mechanisms bringing about complement mediated cell death remain elusive.

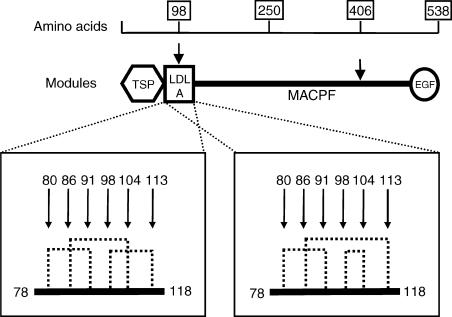

C9 is a monomeric glycoprotein of 538 amino-acids and with a molecular weight of approximately 71 kDa; it comprises independent folding domains/modules7,8 represented in Fig. 1. At the N-terminal end the first two domains have been named following sequence comparisons as thrombospondin type I repeat (TSP I) and low density lipoprotein receptor class A module (LDL-A).7 The central region contains the hinge region and several sections putatively responsible for certain C9 functions such as membrane binding and CD59 recognition; this segment has been called the membrane attack/perforin (MACPF) segment.9 The C-terminal region consists of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) domain.9 C9 contains 24 cysteine residues,10 all of which participate in intramolecular disulphide bond formation. Nine of the 12 disulphide bonds have been assigned definitively11 and the other three all occur within the LDL-A domain, and the bond of Cys98 has been shown tentatively to have only two possible configurations (Fig. 1).11

Figure 1.

Molecular composition of C9. Amino acid numbers, organization of modules, location of the two defects (indicated by arrows) and schematic representation of the two arrangements of disulphide bonding patterns within the LDL-A module of C9 (Cys98 may form a disulphide bridge with Cys 113 or Cys 104) are shown (modified from Lengweiler et al.11). The modules of C9 are: TSP, thrombospondin repeat; LDL-A, low density lipoprotein class A module; MACPF, membrane attack/perforin segment; EGF, epidermal growth factor domain; … represents the intramolecular disulphide bridges. Note that one-quarter of the 12 intramolecular disulphide bridges are located within the LDL-A domain representing approximately 7% of the coding sequence.

In Japan, hereditary deficiency of C9 (C9D) is relatively common12 and, although associated with an increased risk of infections by Neisseria meningitidis, the risk is lower than that in Japanese C7-deficient (C7D) individuals13 or in non-Japanese individuals with deficiencies of the other terminal complement components.14 However, in contrast to the subtotal deficiency reported here, all other known defects responsible for C9 deficiency15–17 lead to complete lack of functionally active C9. Subtotal deficiencies of functionally active terminal complement proteins have not been reported as frequently as total functional deficiencies; however, reports of subtotal C6 deficiencies do suggest that that condition does not carry the same high risk of recurrent N. meningitidis infections as total C6 deficiency.18

In this paper we report experiments on an abnormal C9 protein found in an Irish family with subtotal C9 deficiency (C9SD). The index case had only 0·2% of normal levels of free C9; however, this residual protein was functionally active and could be incorporated into the terminal complement complex (TCC). The patient and his affected sister had quantitatively similar reduced, but positive, levels of C9 functional activity. Both were shown to have compound C9 genetic defects.17 Specifically, a C to G transversion defect at DNA position 1284 in exon 9 (amino acid position 406) creates a stop codon, and a T to G exchange at position 359 in exon 4 leads to the replacement of the codon for cysteine 98 by a glycine (C98G). The position of these defects within the C9 gene, and in relation to the domains, is shown in Fig. 1. Therefore, the structure of the abnormal protein(s) in the affected subjects could either have been truncated, or lacking a cysteine, and consequently one intramolecular disulphide bond or, less likely, very low quantities of two abnormal proteins could have been secreted. The first part of this study established that the size of the circulating abnormal protein was approximately the same as that of normal C9, and thus that the circulating defective molecule was the product of the gene with the exon 4 defect. The site of the defect would be within the LDL-A domain, and the missing cysteine 98 would normally have bonded with another cysteine in this domain. In the second part of the study we investigated the functional activity of this protein to determine the consequence of the structural change, and to provide insight into the role of the LDL-A domain in the function of C9.

Materials and methods

Patients and sera

We have ascribed this family from the West of Ireland as family Y; four members of one generation were available Y I-1, Y I-2, Y I-3 and Y I-4. Two siblings with C9SD had been diagnosed previously.17 The index case, Y I-2, was ascertained at the age of 69 years of age when he was hospitalized for vascular disease and amputation of a leg. Complement screening19 showed him to lack alternative complement activity and to have very low levels of classical pathway activity. Further investigations using a double diffusion haemolytic assay20 and serum from a patient with known C9 deficiency (C9D)21 showed the defect to be C9 deficiency. The index case suffered diabetes and cardiac disease and died 3 years later. His elder sister (Y I-1) was found to have the same complement defect. She was aged 72 years and complained of arthritis, but was otherwise healthy. The other two siblings were complement sufficient, although a second sister (Y I-3) was shown to be heterozygous and to carry only the C98G defect.17 None of the four siblings had a history of neisserial infections, but a sister had died aged 22 years, probably of meningococcal meningitis.

Samples of normal human serum (NHS) were obtained from healthy laboratory personnel. C6, C7 and C9-deficient (C6D, C7D and C9D, respectively) sera were from patients lacking all functional activity of the respective complement components.21–23 The C8 protein, C8-depleted serum and C9-depleted serum were produced as described previously.24 All sera and purified complement preparations were stored at − 70°. Heat-inactivated serum (HIS) was produced by heating NHS to 56° for 30 min.

ELISA assays for C9 and the TCC

Quantitation of C9 was based on polyclonal goat anti-C9 IgG ELISAs using the commercially available goat anti-C9 IgG (Cytotech, La Jolla, CA) or rabbit anti-C9 IgG (kindly provided by B. Bradt, La Jolla,CA, USA), which yielded comparable results, and measurement of TCC was based on a neoepitope-specific mAb25 as described in detail elsewhere.17,26 Complement activation was carried out using boiled baker's yeast.26 For quantitation in ELISAs enzymatic degradation of p-nitrophenylphosphate (Sigma, St Louis, MO) dissolved in AP-buffer (0·1 m glycine; 0·001 m MgCl2; 0·001 m ZnCl2; pH 10·4) by streptavidin- (Pierce, Rockford, IL) or avidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) was measured at 405 nm using a reference wavelength of 492 nm.

Immunoaffinity purification of normal C9 and C9SD proteins

Anti-C9 mAb Mc 4722 (1 ml at 5 mg/ml) was coupled to cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (1·43 g) (Pharmacia Biotech, St Albans, UK) as described previously.24 The final preparation was divided between two 2·5 ml columns. One column was used for the purification of normal C9 protein from 8 ml of NHS, and the other for the purification of the C9SD protein from 5 ml of the C9SD serum. The resulting protein preparations were investigated in serological and functional assays.

SDS-PAGE and experiments to identify and localize C9 bands

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed with a discontinuous buffer system,27 a constant current of 35 mA, and stacking and separating gels of 5% (w/v) and 10% (w/v) acrylamide, respectively. For the functional overlay assay gels were loaded with normal human serum (NHS) (diluted 1 : 50) and C9SD serum (diluted 1 : 10) in reducing sample buffer (0·1 m Tris-HCl (pH 6·8), 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) sodium dodecylsulphate (SDS), 0·1% (w/v) bromophenol blue and 0·06% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol) or non-reducing sample buffer (with β-mercaptoethanol omitted). Alternatively, gels were loaded with affinity purified C9 and C9SD protein preparations diluted 1:2 in the above buffers and electrophoresed in the same way.

Following electrophoresis of the purified proteins, gels were subjected to Western blotting28 and the resultant nitrocellulose membranes were probed with the anti-C9 mAbs (see below). The second antibody was goat antimouse IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The resultant bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Identification of functionally active C9 bands was by a modification of the method described by Orren et al.29 Briefly, after electrophoresis on 10% (w/v) polyacrylamide SDS-PAGE gels the polyacrylamide slabs were washed free of SDS with 0·25% (v/v) Triton X100 for 1 hr; subsequently gels were washed in distilled water for 1 hr, and finally in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7·2 (PBS) for 15 min. C9 indicator gel overlays were then poured over the gels. The indicator gels were made as previously described30 except that the developing reagent was C9-depleted serum instead of C6 deficient serum. The C9 haemolytic bands were visualized after 4–6 hr incubation at room temperature.

C9 epitope mapping using mAbs

The purified C9 and C9SD proteins were subject to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting and primary probing was with previously described anti-C9 mAbs. These were 11.60, Mc34, B7, Mc40, Mc42 and Mc47.7,24

Haemolytic activity of purified C9 and C9SD proteins

Sheep erythrocytes (E) (TCS Microbiology, Buckingham, UK) were sensitized with antisheep erythrocyte antibody (Behring Diagnostics, Milton-Keynes, UK) and complement components up to, and including C7, using C8-depleted serum, to produce EAC1-7.19 C8 was provided by adding 70 µl of purified C8 protein (1·5 mg/ml) to 5 ml of complement-fixing diluent (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) with 0·1% (w/v) gelatine and this solution was used as diluent in the assay.

The functional activity of the C9 and C9SD proteins was assessed by making 200 µl doubling dilutions of the purified preparations in a round-bottomed microtitre plate, adding 10% EAC1-7 and incubating the plate at 37° for 15 min. Subsequently, the plate was centrifuged at 1000 g for 3 min, and 50 µl of the supernatant was aliquoted into wells of a flat-bottomed microtitre plate, followed by the addition of 200 µl of distilled water. The absorbance of the released haemoglobin was read at 415 nm, and haemolytic activity was correlated with concentrations of the C9 and C9SD proteins.

Growth, radio-labelling of Escherichia coli J5(2877), and the release of LPS

Escherichia coli J5(2877) is a substrain of E. coli J5. E. coli J5 strains are galactose epimerase-negative mutants derived from E. coli 0111-B4 that can incorporate exogenous galactose exclusively in the LPS component of the bacterial outer membrane.31E. coli J5(2877) was obtained from Dr B. J. Appelmelk (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, the Netherlands); its properties32 and use for determining the ability of complement proteins to mediate LPS release have been described elsewhere.5

The LPS of E. coli J5(2877) was radiolabelled during growth of the bacteria in basic salts medium33 supplemented with 4 µCi/mmol of tritiated galactose (3H-galactose) (Amersham International, Amersham, UK) to mid-logarithmic phase and LPS release was determined as described.5 Briefly, total counts of [3H]-galactose incorporated into the LPS of the washed bacteria were determined by liquid scintillation counting. Subsequently, the [3H]-labelled bacteria were incubated for up to 3 hr at 37° with either 160 µl of basic salts medium (controls), or 160 µl of basic salts medium containing 50% (v/v) serum, and were used in the LPS release assays. The amount of serum-released 3H-LPS in the supernatant was expressed as a percentage of the total detectable [3H] incorporated into the LPS of E. coli J5(2877).

Serum bactericidal assay

Unlabelled E. coli J5(2877) were prepared and centrifuged as described for the LPS release assay. The pellets were resuspended at a concentration of between 5 × 108 and 1 × 109 colony forming units (cfu)/ml in 200 µl of basic salts medium containing 50% (v/v) serum, and incubated over 3 hr at 37°. At times 0, 0·5 (NHS only), 1·0, 2·0 and 3·0 hr, serial 10-fold dilutions in sterile PBS were plated onto tryptic soy agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 0·25% (w/v) glucose and 0·25% (w/v) galactose and incubated for 16 hr at 37°. All plating was performed in triplicate and bacterial viability was assessed by determining the mean number of cfu/ml.

Results

C9 and TCC levels in affected members of family Y

The low C9 haemolytic activities of the proband Y I-2 and his affected sister Y I-1 have already been reported.17Table 1 shows the C9 levels and TCC levels, as determined by ELISA assays, in the affected siblings and the heterozygous deficient sister, Y I-3 (C9 normal/C9(C98G)). Results for a C9D subject (subject X) with no functional activity17,20 are shown for comparison. Despite the very low C9 levels in subjects Y I-1 and Y I-2, both were able to form TCC, whereas virtually no TCC was formed in the serum from subject X. The heterozygous subject Y I-3 had a C9 level approximately half that found in normal individuals.

Table 1.

Serum C9 and TCC concentrations of homo- and heterozygous C9 deficient individuals

| Concentration (%) in serum of individuals (range in brackets) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complement component | Y I-1 | Y I-2 (index case) | Y I-3 | X | Normal |

| C9 | 0·1 | 0·2 | 48 | 1·2 | 10 (60–140) |

| TCC in non-activated serum | 25 | 30 | 88 | <1 | 100 (30–220) |

| TCC in activated serum | 60 | 45 | 2170 | <1 | 6000 (1200–11 000) |

Identification of the type of abnormal protein circulating in the affected subjects

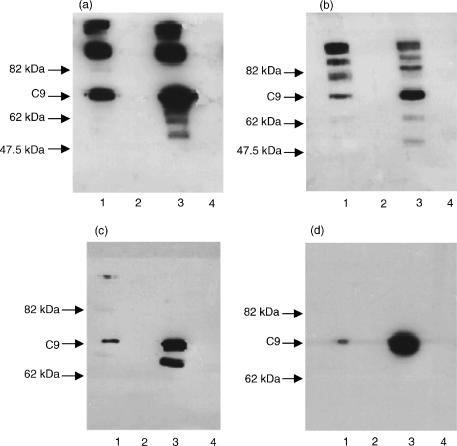

Identification of functionally active C9 bands after SDS-PAGE revealed one faint, but definite, band of C9 functional activity in the C9SD track with the same relative electrophoretic mobility (same Mr of 71 kDa) as the band for C9 in NHS (data not shown). SDS-PAGE gels of affinity purified C9 from NHS, and from C9SD serum were also subjected to Western blotting and band visualization was performed with anti-C9 mAbs. Again, the Mr of the C9SD protein was the same as that of normal C9 (Fig. 2). Therefore, we concluded that the abnormal protein circulating in the affected siblings was the product of the C98G defective C9 gene, which generated a protein of abnormal configuration but normal size.

Figure 2.

Results of SDS-PAGE and Western blotting of purified preparations of normal C9 and C9SD probed with two of the anti-C9 mAbs. In all gels: track 1, C9SD, track 3, normal C9, and tracks 2 and 4 empty. Gels (a) and (b), unreduced and reduced samples, respectively, probed with mAb 11.60. Gels (c) and (d), unreduced and reduced samples, respectively, probed with mAb Mc47. mAb 11.60 reacts with monomeric and polymerized/aggregated C9, whereas Mc47 reacts almost exclusively with monomeric C9. The positions of molecular weight markers and normal C9 are indicated.

Epitope mapping

The lack of a cysteine at position 98 and the lack of a disulphide bond within the LDL-A module could potentially affect the expression of epitopes on the C9SD molecule. In the Western blots, all six mAbs reacted with the 71 kDa band in the tracks with both unreduced C9 and unreduced C9SD proteins. The only mAbs whose epitopes were diminished markedly by reduction of the antigens were B7 and Mc40, and the effect of reduction applied equally to the C9 and C9SD proteins. As can be seen in Fig. 2, mAb 11.60 recognized both the monomeric C9 and higher molecular weight bands that represented polymeric C9, aggregated C9, or possibly C9 within the TCC, and these reactions occurred with epitopes of both the normal C9 and C9SD proteins. In contrast, Mc47 reacted with virtually only momomeric C9. The epitope for Mc34 has been shown to be included in a large region in the N-terminal half of C9.7 Our results showed poor binding of mAb Mc34 to reduced C9 and C9SD proteins; however, strong bands were visible at the 71 Mr position for both the unreduced preparations (data not shown). Significantly, Mc42 also bound to epitopes of both proteins. Epitope mapping has shown the epitope of Mc42 to be in the region of amino acid 406.7 However, a later study showed the reactive epitope in this region to be formed by amino acids 412–4268 which is downstream of the putative stop codon in exon 9. Thus, binding of C9SD protein by Mc42 is further evidence that the C9SD protein is not the product of the gene with the exon 9 defect.

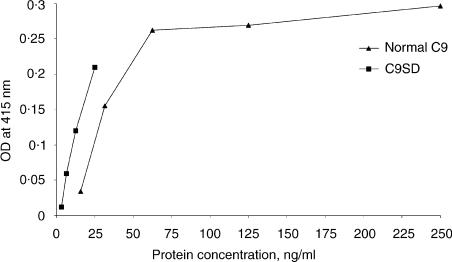

Functional haemolytic activity of C9SD

The C9 concentration of the purified C9 and C9SD preparations were determined by C9 ELISA to be 5·0 and 0·05 µg/ml, respectively. A haemolytic activity curve was obtained for the C9 and C9SD preparations (Fig. 3). It can be seen at all points on the curves, which were established by duplicate assays, that the C9SD protein appeared more potent in producing complement dependent haemolysis than the C9 protein. To quantify this, the relative amount of C9SD to C9 protein required to produce 50% haemolysis was calculated and determined to be approximately 1:2.

Figure 3.

Functional haemolytic activity of purified C9 and C9SD preparations. Haemolytic activity was measured by the optical density (OD) of the test samples at 415 nm.

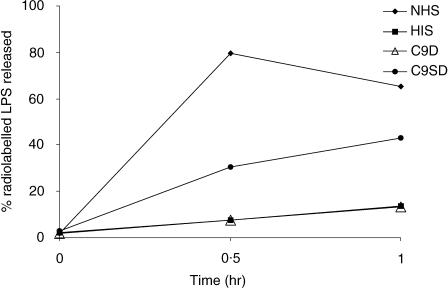

Release of LPS by C9SD

Figure 4 shows the percentages of LPS released from E. coli J5(2877) by NHS, C9SD serum, C9D serum and HIS. NHS produced a high (80%) maximum release of LPS by 0·5 hr. The C9SD serum was active in producing LPS release despite the very low level of C9SD present; however, the release was slower and less prominent than that produced by NHS with 43% LPS released at 1 hr. Only a negligible release was produced by C9D from subject X or by HIS.

Figure 4.

Release of [3H]-labelled LPS from E. coli J5 (2877) by NHS and C9SD serum over 1 hr. Release of LPS by HIS and C9D serum lacking all C9 functional activity, included for comparison.

Bactericidal activity of C9SD serum

This was determined using the serum-sensitive strain E. coli J5, (2877). After 1, 2 and 3 hr incubation >99·9% of bacteria had been killed in 50% NHS, and 98·7%, 99% and >99·9% of bacteria, respectively, had been killed in 50% C9SD serum. After 1 hr of incubation in the C9D serum from subject X only 73% of bacteria were killed, and in C6D or C7D serum the number of cfu increased.

Discussion

An earlier study of C9 gene DNA sequences demonstrated the segregation of two abnormal C9 genes in this family, with Y I-1 and Y I-2 carrying both defective genes.17 However, these subjects did have low functional activity and were subtotal C9 deficient. In the present study we have shown the C9SD protein carried the epitope for mAb Mc42 which would be very unlikely for a product of the exon 9 defect gene. Moreover, the functionally active C9SD protein has the same molecular weight as normal C9. Therefore, the C9SD protein must be the product of the gene with the C98G defect. This protein lacks the cysteine 98, and hence, lacks one of the 12 disulphide bridges present in normal C9. The C9SD molecule would have a normal Mr, but could have structural and functional abnormalities. Nine of the 12 C9 disulphide bridges have been confidently ascribed, but not that including Cys98. Lengweiler and co-authors11 have shown that Cys98-Cys104 or Cys98-Cys113 (Fig. 1) are the most probable configurations for this bond. In either case the bond occurs within the LDL-A receptor domain.

We compared reactivity of a series of mAbs with C9 and C9SD proteins in order to determine changes in the expression of epitopes in the C9SD protein. The six mAbs used did not demonstrate any marked differences in their reactivity. Figure 2 shows that mAb 11.60 reacted both with the monomeric protein from both preparations, and with polymerized or aggregated C9 and C9SD proteins. The presence of reactive high molecular weight bands in the reduced gels indicates the presence of strong covalently linked polymers resistant to reduction and SDS2,34 in both the C9 and C9SD protein preparations. The relative intensities of the bands in the reduced mAb 11.60 gels show that C9SD is only slightly more susceptible to polymerization than C9. The missing cysteine at position 98 in C9SD will mean that either Cys104 or Cys113 is left without a ligand. As the gels failed to show differences between the polymerization of C9 and C9SD preparations it seems likely that the free cysteine in the C9SD is buried in the molecule so that dimerization dependent on the free cysteines cannot occur. The gels probed with Mc47, which binds virtually only to monomeric C9, show clearly the binding to proteins of apparently identical molecular weight in the C9 and C9SD protein preparations. The epitope for Mc34 has been shown by Stanley et al.7 to be included in a large region in the N-terminal half of C9. They suggested that difficulties in precise localization of this epitope may have arisen because it is dependent on the structural integrity of the protein. In the present study, we found poor binding of Mc34 to reduced C9 and C9SD, but strong binding to the C9/C9SD bands of the unreduced preparations indicating that any structural abnormalities present in unreduced C9SD did not effect the expression of the Mc34 epitope. In summary, the epitope mapping studies showed the expression of the same epitopes, under the same conditions, in the C9SD protein preparation as in the C9 preparation.

Functional studies of TCC formation (Table 1), haemolytic activity (Fig. 3), ability to release LPS (Fig. 4) and bactericidal activity all showed the C9SD protein to be functionally active. Interestingly, in the functional haemolytic assay, the C9SD protein appeared slightly more potent than normal C9. This conclusion depends on the result of quantifying an abnormal C9SD protein with polyclonal antibodies raised against the normal protein. However, the C9SD serum contained only 0·2% of the normal C9 protein level of NHS, thus the low concentration of 0·05 µg/ml found in the C9SD preparation is not surprising. In the LPS release assays, C9SD serum containing 0·2% of the normal C9 level released 43% of total LPS after 1 hr, whereas maximum LPS release by normal serum was 79% (Fig. 4). If increased potency of the C9SD protein is confirmed, this will indicate a role for the LDL-A domain in the control of these functions of C9.

The absence of abrogation of C9 functions in the C9SD protein is not surprising given the defect is within the LDL-A domain, and that so far this region has not been shown to be involved in any of the functional activities investigated in this study. On the other hand, the full functionality of the C9 molecule itself is not yet known, and the relevance of this cysteine-rich region needs to be investigated. The C9 LDL-A module bears sequence homology with repeats found in the plasma low-density lipoprotein receptor.7 This protein is a cholesterol transport protein, and is the prototype of a family of cell surface receptors which mediate endocytosis on multiple ligands35 and share common structural elements, including the cysteine-rich ligand binding repeats.36 Some time ago Rosenfeld and co-workers37 showed inhibition of C9 polymerization by high- and low-density lipoproteins; therefore, by providing the ligand, the LDL-A region may have a role in the regulation of MAC activity. Stanley and co-workers7 showed that the LDL-A region must remain exposed after polymerization and suggested that it confers C9 with its high stability towards proteases and detergents, which is a common property of cysteine-rich proteins. Interestingly, Dupuis and co-workers38 studied the effect of point mutations on several C9 domains. Mutations in the lipid-interactive domain between residues 305 and 421 both prevented protein secretion, and altered haemolytic efficiency. In contrast, mutations within the LDL-A at positions 90 (R → A) and 97 (R → S) had no effect on haemolytic activity or level of secretion of the product. In this study we have shown that a mutation in the neighbouring residue 98 which led to the replacement of a cysteine does not diminish haemolytic efficiency. This may be because the other intramolecular disulphide bridges in the vicinity provide sufficient conformational stabilization. However, the missing cysteine at 98 apparently had a dramatic effect on C9 secretion as only 0·2% of the normal C9 level is present in C9SD serum.

Further study of the C9SD protein will be interesting because it may shed some light onto the role of the LDL-A region in the secretion and functionality of C9 itself. We have shown that the C98G defect was associated with markedly reduced protein levels, although the protein had, if anything, enhanced haemolytic activity. Thus the role of the LDL-A region in C9 functionality needs further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Meningitis Research Foundation (Bristol, UK), the Irish Health Research Board (HRB) and the European Union (BIOMED BMH4-CT96-1005, EU-MBL QLG1-CT-2001–01039). A grant from the HRB/British Council Programme 1999 supported a visit of A.M.O'H to the University of Wales, College of Medicine. We are grateful to Anita Fuchs, Innsbruck, for the drawing of Fig. 1.

Abbreviations

- D

deficient/deficiency

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- LDL-A

low density lipoprotein receptor class A module

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MAC

membrane attack complex

- MACPF

membrane attack/perforin segment

- SD

subtotal deficient/deficiency

- TCC

terminal complement complex

- TSP

thrombospondin repeat

References

- 1.Podack ER, Tschopp J, Müller-Eberhard HJ. Molecular organization of C9 within the membrane attack complex of complement: induction of circular C9 polymerization by the C5b-9 assembly. J Exp Med. 1982;156:268–82. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.1.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podack ER, Tschopp J. Polymerization of the ninth component of complement (C9): formation of poly (C9) with a tubular ultrastructure resembling the membrane attack complex of complement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:574–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.2.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan BP. Complement membrane attack on nucleated cells: resistance, recovery and non-lethal effects. Biochem J. 1989;264:1–14. doi: 10.1042/bj2640001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joiner KA, Schmetz MA, Sanders ME, Murray TG, Hammer CH, Dourmaskin R, Frank MM. Multimeric complement component C9 is necessary for killing of Escherichia coli J5 by terminal attack complex C5b-9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4808–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.14.4808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Hara AM, Moran AP, Würzner R, Orren A. Complement-mediated lipopolysaccharide release and outer membrane damage in Escherichia coli J5: requirement for C9. Immunology. 2001;102:365–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stolfi RL. Immune lytic transformation. A state of irreversible damage generated as a result of the reaction of the eighth component in guinea pig complement system. J Immunol. 1968;100:46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanley KK, Kocher HP, Luzio JP, Jackson P, Tschopp J. The sequence and topology of human complement component C9. EMBO J. 1985;4:375–82. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanley KK, Herz J. Topological mapping of complement C9 by recombinant DNA techniques suggest a novel mechanism for its insertion into target membranes. EMBO J. 1987;6:1951–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02457.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plumb ME, Sodetz JM. Proteins of the Membrane Attack Complex. In: Volanakis JE, Frank MM, editors. The Human Complement System in Health and Disease. New York: Dekker; 1998. pp. 119–48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiScipio RG, Gehring MR, Podack ER, Kan CC, Hugli TE, Fey GH. Nucleotide sequence of cDNA and derived amino acid sequence of human complement component C9. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7298–302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lengweiler S, Schaller J, Rickli EE. Identification of disulphide bonds in the ninth component (C9) of human complement. FEBS Lett. 1996;380:8–12. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01541-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukumori Y, Yoshimura K, Ohnoki S, Yamaguchi H, Akagaki Y, Inai S. A high incidence of C9 deficiency among healthy blood donors in Osaka, Japan. Int Immunol. 1989;1:85–9. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata M, Hara T, Aoki T, Mizuno Y, Akeda H, Inaba S, Tsumoto K, Ueda K. Inherited deficiency of ninth component of complement: an increased risk of meningococcal meningitis. J Pediatr. 1989;114:260–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Würzner R, Orren A, Lachmann PJ. Inherited deficiencies of the terminal components of human complement. Immunodeficiency Rev. 1992;3:123–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Witzel-Schlömp K, Späth PJ, Hobart MJ, Fernie BA, Rittner C, Kaufmann T, Schneider PM. The human complement C9 gene. Identification of two mutations causing deficiency and revision of gene structure. J Immunol. 1997;158:5043–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kira R, Ihara K, Takada H, Gondo K, Hara T. Nonsense mutation in exon 4 of human complement C9 gene is the major cause of Japanese complement C9 deficiency. Hum Genet. 1998;102:605–10. doi: 10.1007/s004390050749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Witzel-Schlömp K, Hobart MJ, Fernie BA, Orren A, Würzner R, Rittner C, Kaufmann T, Schneider PM. Heterogeneity in the genetic basis of human complement C9 deficiency. Immunogenetics. 1998;48:144–7. doi: 10.1007/s002510050415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orren A, Würzner R, Potter PC, Fernie BA, Coetzee S, Morgan BP, Lachmann PJ. Properties of a low molecular weight complement component C6 found in human subjects with subtotal C6 deficiency. Immunology. 1992;75:10–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrison RA, Lachmann PJ. Complement technology. In: Weir DM, editor. Handbook of Experimental Immunology. Vol. 1. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1986. pp. 39.1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Egan LJ, Orren A, Doherty J, Würzner R, McCarthy CF. Hereditary deficiency of the seventh component of complement and recurrent meningococcal infection: investigations in an Irish family using a novel haemolytic screening assay for complement activity and C7 M/N allotyping. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;113:275–81. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobart MJ, Fernie BA, Würzner R, Oldroyd RG, Harrison RA, Joysey V, Lachmann PJ. Difficulties in the ascertainment of C9 deficiency: lessons to be drawn from a compound heterozygote C9-deficient subject. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;108:500–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.3841281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orren A, Potter PC, Cooper R, du Toit E. Deficiency of the sixth component of complement and susceptibility to Neisseria meningitidis infections. Studies in ten families and five isolated cases. Immunology. 1987;62:249–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Hara AM, Fernie BA, Moran AP, Williams YE, Connaughton JJ, Orren A, Hobart MJ. C7 deficiency in an Irish family: a deletion defect which is predominant in the Irish. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:355–61. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan BP, Daw RA, Siddle K, Luzio JP, Campbell AK. Immuno-affinity purification of human complement C9 using monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol Meth. 1983;64:269–81. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90434-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Würzner R, Schulze M, Happe L, Franzke A, Bieber FA, Oppermann M, Götze O. Inhibition of terminal complement complex formation and cell lysis by monoclonal antibodies. Complement Inflamm. 1991;8:328–40. doi: 10.1159/000463204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Würzner R, Orren A, Potter P, et al. Functionally active complement proteins C6 and C7 detected in C6- and C7-deficient individuals. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;83:430–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1991.tb05656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orren A, Lerch WH, Dowdle EB. Functional identification of serum complement components following electrophoresis in polyacrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulphate. J Immunol Meth. 1983;59:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobart MJ, Lachmann PJ, Alper CA. Polymorphism of human C6. In: Peeters H, editor. Protides of the Biological Fluids. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1975. pp. 575–80. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbein AD, Heath EC. The biosynthesis of cell wall lipopolysaccharide in Escherichia coli. I. The biochemical properties of a uridine diphosphate galactose-4-epimeraseless mutant. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:1919–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Appelmelk BJ, Maaskant JJ, Verrweij-van Vught MJJ, van der Meer NM, Thijs BG, MacLaren DM. Antigenic and immunogenic differences in lipopolysaccharides of Escherichia coli J5 vaccine strains of different origins. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:2641–7. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-11-2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leive L. Actinomycin sensitivity in Escherichia coli produced by EDTA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;18:13–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(65)90874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor KM, Trimby AR, Campbell AK. Mutation of recombinant complement component C9 reveals the significance of the N-terminal region for polymerization. Immunology. 1977;91:20–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bieri S, Djordjevic JT, Daly NL, Smith R, Kroon PA. Disufide bridges of a cysteine-rich repeat of the LDL receptor ligand-binding domain. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13059–65. doi: 10.1021/bi00040a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daly NL, Scanlon MJ, Djordjevic JT, Kroon PA, Smith R. Three-dimensional structure of a cysteine-rich repeat from the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6334–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenfeld SI, Packman CH, Leddy JP. Inhibition of the lytic action of cell-bound terminal complement components by human high density lipoproteins and apoproteins. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:795–808. doi: 10.1172/JCI110833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dupuis M, Peitsch MC, Hamann U, Stanley KK, Tschopp J. Mutations in the putative lipid-interaction domain of complement C9 result in defective secretion of the functional protein. Mol Immunol. 1993;30:95–100. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(93)90430-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]