Abstract

The Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine has variable efficacy for both human and bovine tuberculosis. There is a need for improved vaccines or vaccine strategies for control of these diseases. A recently developed prime-boost strategy was investigated for vaccination against M. bovis infection in mice. BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were primed with a DNA vaccine, expressing two mycobacterial antigens, ESAT-6 and antigen 85 A and boosted with attenuated M. bovis strains, BCG or WAg520, a newly attenuated strain, prior to aerosol challenge. Before challenge, the antigen-specific production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) was evaluated by ELISPOT and antibody responses were measured. The prime-boost stimulated an increase in the numbers of IFN-γ producing cells compared with DNA or live vaccination alone, but this varied according to the attenuated vaccine strain, time of challenge and the strain of mouse used. Animals vaccinated with DNA alone generated the strongest antibody response to mycobacterial antigens, which was predominantly IgG1. BCG and WAg520 alone generally gave a 1–2 log10 reduction in bacterial load in lungs or spleen, compared to non-vaccinated or plasmid DNA only control groups. The prime-boost regimen was not more effective than BCG or WAg520 alone. These observations demonstrate the comparable efficacy of BCG and WAg520 in a mouse model of bovine tuberculosis. However, priming with the DNA vaccine and boosting with an attenuated M. bovis vaccine enhanced IFN-γ immune responses compared to vaccinating with an attenuated M. bovis vaccine alone, but did not increase protection against a virulent M. bovis infection.

Introduction

Bovine tuberculosis in farmed animals is a major problem in countries that have wildlife vectors for the disease. It is also a major problem in countries, which for economic or other reasons cannot use a ‘test and slaughter’ programme where infected animals are identified and removed.1 Another way to approach the problem of bovine tuberculosis would be to vaccinate farmed animals susceptible to the disease. The best vaccine available, Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG), as in human tuberculosis, gives variable protective efficacy against bovine tuberculosis.2,3 New attenuated strains of M. bovis and new generation vaccines, such as recombinant BCG, subunit vaccines and DNA vaccines are being developed for both human and bovine tuberculosis.4–7 The mouse has been used extensively to screen for tuberculosis vaccine efficacy, most commonly against challenge with M. tuberculosis.8 A number of promising immunogenic proteins have been evaluated. Some degree of protective immunity against disease can be generated by mixtures of secreted proteins such those present in culture filtrates prepared from M. tuberculosis8,9 or M. bovis10 and by recombinant proteins such as those of the Ag85 complex and ESAT-6.11 The protection conferred does not usually exceed BCG. It is yet to be demonstrated that a long-lived state of memory can be established using proteins.9 Live vaccines are able to do this and new strains of attenuated M. bovis are being developed. One such strain, WAg520, has been shown to be at least as potent as BCG for protection against experimental M. bovis infection in the guinea pig12 and the possum (unpublished observations).

Although BCG and new attenuated strains may be able to stimulate long-term memory responses there is a concern that they may not have the capacity to stimulate a fully protective immune response. In cattle, humans and mice the major cell involved in protective immunity against tuberculosis appears to be the CD4+ T cell, which produces interferon-γ (IFN-γ).13 Live vaccines are good at stimulating IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells. However, protective immunity is more complex as IFN-γ is produced during infection and development of active disease14,15 and induction of high levels of IFN-γ does not always correlate with protection.16–18 Other T cell subsets have been implicated and in the mouse CD8+ T cells also appear to be required for protection.19,20 BCG is a good stimulator of CD4+ Th1 cell responses. Vaccination strategies which stimulate both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses may be more successful. DNA vaccines can stimulate both CD4+ and CD8+ responses but their protective efficacy is generally less than BCG.5,6 A prime-boost strategy using DNA vaccines and attenuated viral vectors, each expressing similar antigens, has been successful in stimulating protective cell-mediated immune responses against viral infections21 and is currently held to offer the best prospects for protective vaccination against HIV.22,23 Strategies involving priming with one type of vaccine and boosting with another have had some degree of success against challenge with M. tuberculosis in mice.24–26 Similar strategies may be useful for enhancing protection against M. bovis infections. In this report the efficacy of a prime-boost strategy using DNA encoding ESAT-6 and Ag85A to prime and BCG to boost was evaluated for protection in mice against an aerosol challenge with M. bovis. A newly attenuated non-virulent strain of M. bovis, WAg520, that expresses both ESAT-6 and Ag85, was also investigated as a boost component.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the Animal Resource Centre, Perth, Australia and were housed in containment facilities at AgResearch Wallaceville. All procedures on the mice had the approval of the Wallaceville Research Centre Animal Ethics Committee (Upper Hutt, New Zealand).

DNA vaccine construction

DNA encoding a fusion of Ag85A and ESAT-6 was prepared as described elsewhere.27 Next, a DNA fragment encoding the 25 amino acid secretion signal sequence from Oncostatin M was generated by primer extension28 and ligated in-frame to the Ag85A/ESAT-6 DNA fusion in pGEM-T. Finally, an ApaI/NheI fragment, encoding the signal sequence, Ag85A and ESAT-6, was cloned into the plasmid pJW4303 immediately distal to the CMV promoter to create a DNA vaccine encoding a secreted fusion of Ag85A and ESAT-6. pJW4303 was used as the plasmid control vaccine. Plasmids were adjusted to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml in PBS and stored at − 20°.

Mycobacteria

Mycobacteria were grown to mid-log phase in Tween albumin broth using Dubos broth base (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) supplemented with 0·006% (v/v) alkalinized oleic acid, 0·5% (wt/vol) albumin fraction V and 0·25% (wt/vol) glucose. The avirulent strains used for vaccination were M. bovis BCG Pasteur 1173P and M. bovis WAg520, a newly attenuated M. bovis strain produced at AgResearch Wallaceville by illegitimate recombination.12 In comparison to the Sanger sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv, WAg520 has a kanamycin resistance gene inserted into a 2-base pairs (bp) deletion of the coding region of Rv2136c and the disruption of this single region causes the organism to become attenuated. The challenge strain, WAg201, was a wild-type virulent M. bovis strain isolated from a tuberculous lesion of a New Zealand cow.

Mycobacterial antigens

Purified protein derivative from M. bovis (bovine PPD) was obtained from CSL Ltd (Melbourne, Australia). Ag85A and ESAT-6 were produced as His6 tagged recombinant proteins from E. coli transformed with pET32a (Novagen, USA) containing Ag85A or ESAT-6 DNA and purified over Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Germany). A sample was run on SDS-PAGE to confirm the expressed protein was of the appropriate size. The amount of protein in each sample was determined using the Bradford dye binding procedure.

Vaccination and challenge procedure

The vaccination and challenge schedules of mice are shown in Table 1. Groups of BALB/c and C57BL/6 (n = 11) were primed with plasmid DNA, control plasmid or PBS at week 0 and week 4. They were boosted with plasmid DNA, control plasmid, BCG or WAg 520 at week 8. Priming comprised of an intramuscular injection of 100 µg of plasmid in PBS or PBS alone delivered as two injections of 50 µl into each quadriceps under anaesthesia. A boost vaccination of 1 × 106 organisms of M. bovis BCG or WAg520 was given subcutaneously as a suspension in 100 µl Tween–albumin broth. To evaluate the level of protection, seven mice were given an aerosol challenge of virulent M. bovis 14 or 24 weeks after the first DNA vaccination. Single cell suspensions of the challenge isolate were prepared using a modification of a method described by Grover et al.29 and stored at − 70°. For preparing these suspensions, the bacterial cells were dispersed by sonication for 30 seconds and filtered through an 8-µm filter. The mice were infected via the respiratory route by using an aerosol chamber which produces droplet nuclei of the size appropriate for entry into alveolar spaces.30,31 The concentration of viable M. bovis in the nebulizer fluid was adjusted empirically to result in the inhalation and retention of approximately 10 viable organisms per mouse. This challenge dose had been estimated previously from culture of mouse lungs within 20 hr of infection. The mice were killed 5 weeks after challenge and serial dilutions of individual lung and spleen homogenates were plated out on a modified 7H11 agar32 Bacterial colonies were counted 28 days later following incubation at 37° in humidified air.

Table 1.

Vaccine groups and challenge schedule

| Vaccine groups Prime × 2 | Boost | Mouse strain | Time of challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBS | PBS | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| DNA | DNA | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | Plasmid | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| PBS | BCG | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| PBS | WAg520 | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | BCG | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | WAg520 | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| DNA | BCG | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| DNA | WAg520 | BALB/c | 14 weeks |

| PBS | PBS | BALB/c | 24 weeks |

| DNA | DNA | BALB/c | 24 weeks |

| DNA | BCG | BALB/c | 24 weeks |

| DNA | WAg520 | BALB/c | 24 weeks |

| PBS | PBS | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| DNA | DNA | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | Plasmid | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | BCG | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| Plasmid | WAg520 | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| DNA | BCG | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

| DNA | WAg520 | C57BL/6 | 14 weeks |

IFN-γ responses

Four mice from each vaccine group were not challenged but killed on the day of challenge, and single cell suspensions of spleen cells were assayed by ELISPOT for IFN-γ producing cells. ELISPOT assays were prepared using MAHA S45 plates (Millipore, MA, USA) which had been coated overnight with rat anti-mouse IFN-γ capture antibody (RA-6A2; Pharmingen, CA, USA) at 2 µg/ml. The following day they were washed with PBS, blocked with BSA, re-washed with PBS and plated with spleen cells in 100 µl DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 110 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, 60 mg/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 2 mm glutamine (TC medium) at 2 × 105 and 5 × 104 cells per well. They were incubated with ESAT-6 (17·5 µg/ml), Ag85A (17·5 µg/ml), bovine PPD (60 µg/ml), concanavalin A (Sigma Chemical Co., MO, USA) (5 µg/ml, positive control) or alone (negative control). After 24 hr the plates were washed with PBS containing 0·05% Tween (PBST). Biotinylated detection rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMGI.2, Pharmingen) was added at 2 µg/ml and plates were incubated overnight at 4°. The next day plates were washed again with PBST and incubated for 2 hr at room temperature with streptavidin alkaline phosphatase (Amersham, UK) diluted 1/2000 in PBS. The plates were washed again and spots were developed at 4° with BCIP-NBT (Sigma). The plates were washed with copious amounts of tap water, air-dried and spots counted using a low-power microscope. Background ELISPOTS from the negative controls were negligible.

Antibody determinations

An ELISA was used to determine IgG1 and IGg2a antibody specific for Ag85A and ESAT-6. Briefly, 96-well plates (Nunc, Denmark) were coated with Ag85A or ESAT-6 (50 µl of 50 µg/ml) in 0·1 m NaHCO3 pH 8·2 and incubated overnight at 4°. After being washed in PBST the plates were blocked with PBS + 10% fetal calf serum (v/v) (PBS/FCS) for 2 hr at room temperature. The plates were washed prior to the addition of serum diluted in PBS/FCS and left at room temperature for 1 hr. After washing, goat anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a (Pharmingen) diluted 1/1000 in PBS/FCS was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The plates were washed and rabbit antigoat peroxidase conjugate (Sigma) diluted 1/3000 in PBS/FCS added. After 15 min at room temperature the plates were washed, substrate added and plates read. IgG1 and Ig2a standards (Pharmingen) were used to determine antibody levels in pooled serum samples of each group prior to challenge with virulent M. bovis.

Analysis of results

Means and standard deviations of ELISPOT values were determined from the means of triplicate or quadruplicate cultures and differences between vaccine groups were determined by analysis of variance. Analysis of bacterial counts from the M. bovis challenged mice was carried out by analysis of variance on log 10 transformed data.

Results

IFN-γ responses

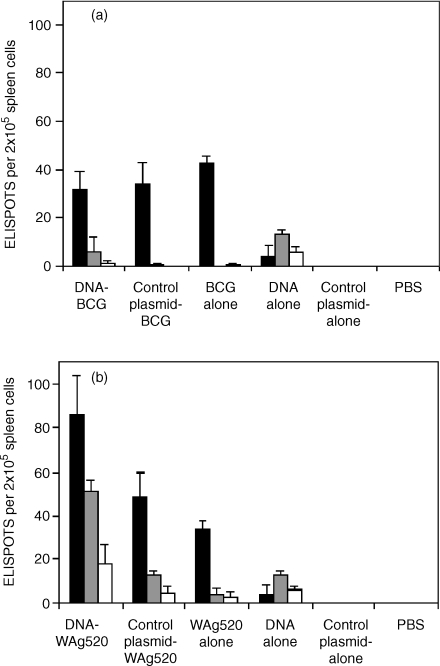

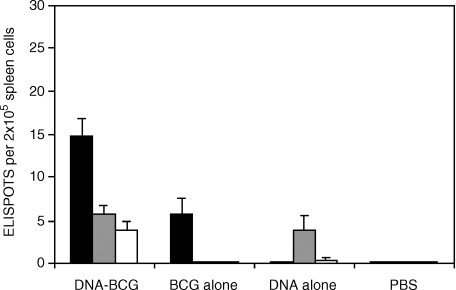

Experimental groups of BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice were primed with plasmid DNA and boosted with BCG or WAg520. Control groups received the prime alone, the boost alone or were primed with control plasmid only or control plasmid before BCG/WAg520 boosting. IFN-γ responses were measured in four mice of each group by ELISPOT prior to challenge. With BALB/c mice, at 14 weeks after the first vaccination a weak response to bovine PPD, ESAT-6 and Ag85A was detected after DNA vaccination (Fig. 1). A stronger response to bovine PPD was detected after vaccination with BCG (Fig. 1a) or WAg 520 alone (Fig. 1b). After the boost with BCG there was little difference in IFN-γ responses to bovine PPD and Ag85A compared to vaccination with control plasmid and BCG or BCG alone and, as expected, no boosting of ESAT-6 responses (Fig. 1a). Boosting with WAg520 after the DNA prime gave a significant increase in the number of IFN-γ-secreting cells responding to bovine PPD (P < 0·001), ESAT-6 (P < 0·001) and Ag85A (P < 0·01) compared to when WAg520 was used after priming with control plasmid (Fig. 1b). In addition the WAg520 boost was significantly better than the BCG boost (P < 0·001) after DNA priming but not after priming with control plasmid. The effect of BCG boosting was also studied in BALB/c mice 24 weeks after the first vaccination. The number of IFN-γ-secreting cells after BCG alone was maintained (Fig. 2). In the prime-boost group there were now significantly more bovine PPD-specific IFN-γ-secreting cells than with BCG alone (P < 0·01).

Figure 1.

Interferon-γ-secreting cells in BALB/c mice 14 weeks after first vaccination. Mice were primed either with plasmid DNA expressing ESAT-6 and Ag85A or control plasmid before boosting with BCG only (a) or WAg520 (b). Some mice were given plasmid DNA or control plasmid only (no boost) or an attenuated M. bovis only (no prime). IFN-γ responses were measured by ELISPOT in response to bovine PPD (black bars), ESAT-6 (grey bars) or Ag85A (white bars). The means and SD of replicate determinations are shown.

Figure 2.

Interferon-γ-secreting cells in BALB/c mice 24 weeks after first vaccination. Mice were primed with plasmid DNA expressing ESAT-6 and Ag85A before boosting with BCG. Some mice were given only plasmid DNA (no boost) or BCG only (no prime). IFN-γ responses were measured by ELISPOT in response to bovine PPD (black bars), ESAT-6 (grey bars) or Ag85A (white bars). The means and SD of replicate determination are shown.

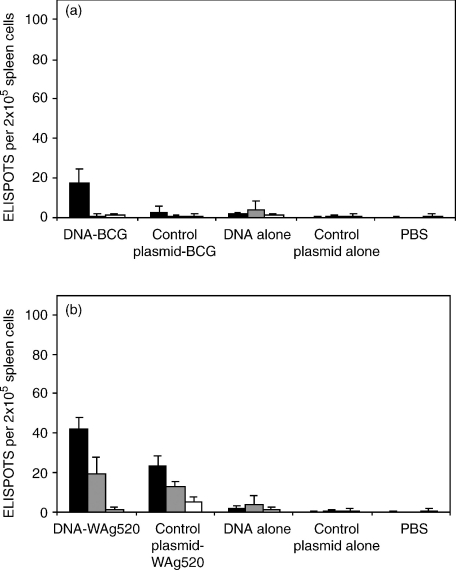

The IFN-γ responses from C57BL/6 mice at 14 weeks were lower overall (Fig. 3). There was a response to bovine PPD from spleen cells of mice primed with DNA and boosted with BCG but this was barely detectable when BCG or DNA alone was used (Fig. 3a). Vaccination with WAg520 after DNA priming induced a significantly better response to bovine PPD (P < 0·001) and ESAT-6 (P < 0·05) than WAg520 vaccination after control plasmid priming. (Fig. 3b). Again the WAg520 boost was significantly better than the BCG boost (P < 0·001) after DNA priming and also after priming with the control plasmid (P < 0·001).

Figure 3.

Interferon-γ-secreting cells in C57BL/6 mice 14 weeks after first vaccination. Mice were primed with plasmid DNA (no boost) expressing ESAT-6 and Ag85A, or control plasmid before boosting with BCG (a) or WAg520 (b). Some mice were given plasmid DNA (no boost) or control plasmid only (no prime). IFN-γ responses were measured by ELISPOT in response to bovine PPD (black bars), ESAT-6 (grey bars) or Ag85A (white bars). The means and SD of replicate determinations are shown.

Antibody responses

IgG1 and IgG2a antibody against Ag85A and ESAT 6 were determined on pooled serum samples of each group of mice before challenge. The results from the C57BL/6 mice are shown in Fig. 4. A strong antibody response was detected in mice that had been vaccinated three times with DNA alone. There was only a weak response from mice vaccinated with an attenuated M. bovis strain alone and it was also low when mice received two vaccinations of DNA followed by an attenuated M. bovis strain. Similar results were obtained in BALB/c mice.

Figure 4.

Antibody responses 14 weeks after first vaccination. C57BL/6 mice were primed with plasmid DNA expressing ESAT-6 and Ag85A, or control plasmid before boosting with BCG or WAg520. Some mice were given plasmid DNA or control plasmid only (no boost). Isotype specific antibody (IgG1 black bars, IgG2a grey bars) against Ag85A (a) and ESAT-6 (b) were measured by ELISA and the mean of pooled sera are shown.

Protective efficacy

Seven mice of each group were challenged with an aerosol infection of M. bovis. Five weeks later mice were killed and colony-forming units (CFU) in spleens and lungs determined. With BALB/c mice challenged at 14 weeks there was significant protection in the lung and spleen in all groups vaccinated with either of the attenuated M. bovis vaccines (P < 0·05), but no increase in efficacy when animals were first primed with the DNA vaccine (Table 2). In the lung there was a small but not significant decrease in bacterial counts with both the DNA vaccine and with the plasmid control. When BALB/c mice were challenged at 24 weeks there was a significant reduction in bacterial counts in the lung after DNA vaccination and in both the spleen and lung after BCG vaccination (P < 0·05). Again, priming first with DNA did not increase the efficacy of the live attenuated M. bovis vaccine (Table 3). All C57BL/6 mice were challenged at 14 weeks (Table 4). There was significant protection in the lung when DNA alone was compared to control plasmid alone (P < 0·05) and a small but not significant reduction in viable bacteria in the spleen. Once again, however, there was no evidence for an increase in protective efficacy of DNA/mycobacteria prime-boosting when compared to attenuated mycobacteria vaccination alone.

Table 2.

BALB/c mice and challenged with virulent M. bovis 14 weeks after first vaccination

| Vaccine group | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (lung) ± SE | Log 10 protection (lungs)* | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (spleen) ± SE | Log 10 protection (spleen)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS/PBS/PBS | 5·51 (±0·18) | 0† | 3·81 (±0·22) | ″0† |

| DNA/DNA/DNA | 5·18 (±0·11) | 0·33† | 4·22 (±0·16) | −0·41† |

| Plasmid/plasmid/plasmid | 5·15 (±0·34) | 0·35† | 4·40 (±0·19) | −0·58† |

| DNA/DNA/BCG | 4·28 (±0·18) | 1·23‡ | 2·62 (±0·18) | ″1·20‡ |

| DNA/DNA/WAg520 | 4·19 (±0·28) | 1·31‡ | 2·76 (±0·14) | ″1·05‡ |

| PBS/PBS/BCG | 3·86 (±0·23) | 1·65‡ | 2·35 (±0·31) | ″1·47‡ |

| PBS/PBS/WAg520 | 4·39 (±0·24) | 1·12‡ | 2·44 (±0·50) | ″1·37‡ |

| Plasmid/plasmid/BCG | 3·97 (±0·15) | 1·54‡ | 2·58 (±0·12) | ″1·23‡ |

| Plasmid/plasmid/WAg | 4·46 (±0·21) | 1·05‡ | 2·43 (±0·35) | ″1·38‡ |

Groups with same symbol are not significantly different from each other (P > 0·05).

Table 3.

BALB/c mice challenged with virulent M. bovis 24 weeks after first vaccination

| Vaccine group | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (lung) ± SE | Log 10 protection (lungs)* | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (spleen) ± SE | Log 10 protection (spleen)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS/PBS/PBS | 6·04 (±0·19) | 0† | 4·30 (±0·31) | 0† |

| DNA/DNA/DNA | 5·50 (±0·15) | 0·54‡ | 4·20 (±0·19) | 0·1† |

| DNA/DNA/BCG | 4·59 (±0·20) | 1·44§ | 2·75 (±0·17) | 1·55‡ |

| PBS/PBS/BCG | 4·69 (±0·15) | 1·35§ | 2·80 (±0·17) | 1·50‡ |

Groups with same symbol are not significantly different from each other (P > 0·05).

Table 4.

C57BL/6 mice challenged with virulent M. bovis 14 weeks after first vaccination

| Vaccine group | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (lung) ± SE | Log 10 protection (lungs)* | Log 10 mean viable bacteria (spleen) ± SE | Log 10 protection (spleen)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS/PBS/PBS | 4·76 (±0·07) | 0†‡ | 3·97 (±0·14) | 0† |

| DNA/DNA/DNA | 4·28 (±0·68) | 0·49‡ | 3·75 (±0·17) | 0·22† |

| Plasmid/plasmid/plasmid | 5·34 (±0·13) | −0·58† | 3·92 (±0·22) | 0·05† |

| DNA/DNA/BCG | 4·46 (±0·26) | 0·30†‡ | 2·86 (±0·14) | 1·11‡ |

| DNA/DNA/WAg520 | 4·49 (±0·24) | 0·27†‡ | 2·21 (±0·37) | 1·76‡ |

| Plasmid/plasmid/BCG | 4·32 (±0·14) | 0·44‡ | 2·57 (±0·19) | 1·47‡ |

| Plasmid/plasmid/WAg520 | 4·14 (±0·30) | 0·63‡ | 2·57 (±0·27) | 1·40‡ |

Groups with same symbol are not significantly different from each other (P > 0·05).

Discussion

In this work a novel prime-boost vaccination strategy against bovine tuberculosis was shown to increase IFN-γ responses to mycobacterial antigens but failed to enhance protection in an experimental mouse model. Data from animal studies suggest that IFN-γ is the major effector cytokine against mycobacterial infections; however, we have shown, as have others,17,18 that increasing the IFN-γ response does not necessarily induce enhanced protection.

The mycobacterial antigens, ESAT-6 and Ag85A, expressed by the plasmid DNA in the priming step are two candidates for vaccines against tuberculosis. They have been shown to stimulate good IFN-γ responses when given either as a DNA vaccine5 or a subunit vaccine in conjunction with an appropriate adjuvant.11 ESAT-6 is also a candidate for use in diagnosis.33 Our data demonstrate clearly that DNA vaccines effectively primed the immune system for both T cell and antibody-mediated responses against these encoded antigens. For boosting, BCG, which expresses Ag85A but not ESAT-6, was compared with WAg520 which expresses both proteins. It was not surprising to find, therefore, that when WAg520 was used as the boost after DNA priming, the numbers of IFN-γ-secreting cells in response to bovine PPD, ESAT-6 and Ag85A were increased at least twofold in the BALB/c mice at 14 weeks. This increase in IFN-γ-producing cells was due most probably to the presence of both priming antigens in WAg520 although other, undefined properties of this new vaccine strain of M. bovis may have played a role. WAg520 is a defined avirulent mutant of M. bovis with an inactivated gene characterized as encoding a possible undecaprenol kinase,12 while in comparison BCG has a considerable number of known gene duplications and deletions, including esat-6 deletion, and is also likely to have further unidentified mutations.

When BCG was used as the boost, there was no increase in IFN-γ-producing cells at 14 weeks compared with BCG alone. An effect of DNA priming on a BCG boost was, however, detected when the IFN-γ responses were measured at a later time after the initial vaccination (24 weeks, Fig. 2). It is possible that the DNA priming prior to the BCG boost increased the memory potential of the vaccination procedure. Indeed, in virus infection models this type of prime-boost strategy, albeit where attenuated virus vectors are used for the boost, stimulates a high-frequency, high-avidity CD8+ cytotoxic T cell population that responds rapidly to viral challenge.34 In this system the prime-boost appears to be most effective when the boost provides a better antigenic stimulus than the prime. Perhaps mycobacteria are not the best boosting vectors for this type of vaccination strategy. A recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara strain encoding ESAT-6 and mycobacterial protein tuberculosis 63 has been used to boost DNA vaccination in a mouse model of human tuberculosis.25 The DNA prime alone and the boost alone gave similar IFN-γ responses, but although the prime-boost enhanced these 10–20-fold the protection did not exceed that of BCG. Of course, this strategy might be useful for bovine tuberculosis as it may present less of a challenge to distinguish between vaccinated animals and those with disease.

The IFN-γ responses in the C57BL/6 mice were lower than in the BALB/c mice and differences in cytokine responses to mycobacterial antigens between these mouse strains has been reported.35 A response with DNA alone was barely detectable in C56BL/6 mice. They responded to bovine PPD after BCG vaccination but only when primed first with plasmid DNA and no response to Ag85A could be detected. However when WAg520 was used it was possible to detect responses to ESAT-6. This was increased when animals were first primed with DNA, as was the response to bovine PPD. The results demonstrate that in general DNA priming is having an enhancing effect on the IFN-γ response after boosting with BCG or WAg520, but there are definite differences between BALB/c and C57BL/6 mouse strains. Presumably there would similarly be differences between individual animals of an out-bred population of cattle.

DNA vaccination induced a strong antibody response with an IgG1 isotype profile. Thus, when the DNA vaccine only was given there was successful immunization for stimulation of specific antibody responses against the encoded mycobacterial antigens, demonstrating that the vaccine was adequate for stimulating an immune response. Boosting with BCG or WAg520 resulted in a reduced antibody response. In cattle, protection against experimental infection with M. bovis is not associated with strong antibody responses after vaccination.15

Although the prime-boost regime led to an enhanced IFN-γ response and a low antibody response it did not lead to increased protection. It is possible that the DNA prime influenced the capacity of BCG or WAg520 to proliferate in the mice. Pre-exposure to environmental mycobacteria can have this effect, decreasing the efficacy of BCG,36 but there was no decrease in protection in this work. Indeed, the DNA/mycobacteria prime-boost strategy gave the same level of protection as one of the two attenuated M. bovis vaccines when used alone. Another possible explanation comes from recent work on the induction and maintenance of memory responses, as induction of strong IFN-γ responses can lead to a lack of memory cells.37

WAg520 has previously been shown to be as good as BCG in protection against experimental M. bovis infection of the guinea pig12 and possum (unpublished observations). The results presented in this report clearly demonstrate that WAg520 is as good as BCG in a mouse infection model. The fact that it expresses ESAT-6 does not appear to make it a better vaccine strain. A single injection of BCG or WAg520 reduced the number of live mycobacteria in both the lungs and the spleen of BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice following a low dose aerosol challenge with M. bovis. The DNA vaccine alone gave a reduction of bacteria in the lungs in C57BL/6 mice, in the order of 0·5 logs, which is in agreement with other recent studies.24,26 However, a prime-boost strategy similar to the one used in this work reported better protection in the spleen compared with BCG alone.26 There were a number of differences in the experimental design. Ag85B plasmid DNA was used, BCG alone was given at the same time as the plasmid DNA, the Tokyo strain of BCG was used and mice were challenged with M. tuberculosis. The efficacy of different BCG strains has been demonstrated38 and it will be instructive to determine whether the prime-boost strategy has the same effect when these different BCG strains are used. It would also be useful to determine whether the prime-boost approach could be used as a strategy to increase the effectiveness of BCG when it is not functioning optimally, for example after pre-exposure to environmental mycobacteria.36,39 Future work is aimed at addressing this question in cattle.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Rich and G. F. Yates for excellent technical assistance, H. Robinson for kindly supplying the pJW4303 plasmid and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Policy Management), New Zealand for financial support.

References

- 1.Skinner MA, Wedlock DN, Buddle BM. Vaccination of animals against Mycobacterium bovis. Rev sci tech Off int Epiz. 2001;20:112–32. doi: 10.20506/rst.20.1.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fine PE. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet. 1995;346:1339–45. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buddle BM, Aldwell F, Wedlock DN. Vaccination of cattle and possums against bovine tuberculosis. In: Griffin F, de Lisle G, editors. Tuberculosis in Wildlife and Domestic Animals. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press; 1995. pp. 113–5. Otago Conference Series no. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slobbe L, Lockhart E, O'Donnell M, Makintosh C, Buchan G. An in vitro comparison of BCG and cytokine secreting BCG vaccines. Immunology. 1999;96:517–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00702.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin SL, D'Souza C, Roberts AD, et al. Evaluation of new vaccines in the mouse and guinea pig model of tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2951–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2951-2959.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowrie DB, Silva CL, Colston MJ, Ragno S, Tascon RE. Protection against tuberculosis by a plasmid DNA vaccine. Vaccine. 1997;15:834–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buddle BM. Vaccination of cattle against Mycobacterium bovis. Tuberculosis. 2002;81:125–32. doi: 10.1054/tube.2000.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orme IM, McMurray DN, Belisle JT. Tuberculosis vaccine development: recent progress. Trends Micro. 2001;9:115–8. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01949-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts AD, Sonnenberg MG, Ordway DL, Furney SK, Brennan PJ, Belisle T, Orme IM. Characteristics of protective immunity engendered by vaccination of mice with purified culture filtrate protein antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1995;85:502–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosio CM, Orme IM. Effective, nonsensitizing vaccination with culture filtrate proteins against Mycobacterium bovis infections in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5048–51. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.5048-5051.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt L, Elhay M, Rosenkrands I, Lindblad E, Andersen P. ESAT-6 subunit vaccination against. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infect Immun. 2000;68:791–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.791-795.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lisle GW, Wilson T, Collins DM, Buddle BM. Vaccination of guinea pigs with nutritionally impaired avirulent mutants of Mycobacterium bovis protects against tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2624–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2624-2626.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wedlock DN, Skinner MA, deLisle GW, Buddle BM. Control of Mycobacterium bovis infections and the risk to human population. Microbes Inf. 2002;4:471–80. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(02)01562-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilsher ML, Hagan C, Prestidge R, Wells AU, Murison G. Human in vitro immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79:371–7. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wedlock DN, Vesosky B, Skinner MA, de Lisle GW, Orme IM, Buddle BM. Vaccination of cattle with Mycobacterium bovis culture filtrate proteins and interleukin-2 for protection against bovine tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5809–15. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5809-5815.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hook S, Griffin F, Makintosh C, Buchan G. Activation of an interleukin-4 mRNA-producing population of peripheral blood mononuclear cells after infection with Mycobacterium bovis or vaccination with killed, but not live, BCG. Immunology. 1996;88:269–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.1996.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leal IS, Smedegard B, Andersen P, Appelberg R. Failure to induce enhanced protection against tuberculosis by increasing T-cell-dependent interferon-gamma generation. Immunology. 2001;104:157–61. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young S, O'Donnell M, Lockhart E, Buddle B, Slobbe L, Luo Y, De Lisle G, Buchan G. Manipulation of immune response to Mycobacterium bovis by vaccination with IL-2 and IL-18 secreting recombinant BCG. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80:209–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller I, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H, Kaufmann SHE. Impaired resistance against Mycobacterium tuberculosis after selective in vivo depletion of L3T4+ or Lyt2+ T cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2037–41. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.2037-2041.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flynn JL, Goldstein MM, Triebold KJ, Koller B, Bloom BR. Major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted T cells are required for resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12013–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ. The prime-boost strategy: exciting prospects for improved vaccination. Immunol Today. 2000;21:160–2. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amara RR, Villinger F, Altman JD, et al. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science. 2001;292:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1058915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiver JW, Fu TM, Chen L, et al. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature. 2002;415:331–5. doi: 10.1038/415331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanghe A, D'Souza S, Rosseels V, Denis O, Ottenhoff THM, Dalemans W, Wheeler C, Huygen K. Improved immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding Ag85 by protein boosting. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3041–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.3041-3047.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McShane H, Brookes R, Gilbert S, Hill AVS. Enhanced immunogenicity of CD4+ T-cell response and protective efficacy of a DNA-modified vaccinia virus Ankara prime-boost vaccination regimen for murine tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:681–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.681-686.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng CG, Palendira U, Demangel C, Spratt JM, Malin A, Britton W. Priming with DNA immunisation augments protective efficacy of Mycobacterium bovis Bacille-Calmette–Guerin against tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:4174–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.4174-4176.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weinrich Olsen A, van Pinxteren LA, Meng Okkels L, Birk Rasmussen P, Andersen P. Protection of mice with a tuberculosis subunit vaccine based on a fusion protein of antigen 85b and esat-6. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2773–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2773-2778.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drew DR, Lightowlers M, Strugnell RA. Humoral immune responses to DNA vaccines expressing secreted, membrane bound and non-secreted forms of the Taenia ovis 45W antigen. Vaccine. 2000;18:2522–32. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grover AA, Kim HK, Wiegeshaus EH, Smith DW. Host–parasite relationships in experimental airborne tuberculosis. II. Reproducible infection by means of an inoculum preserved at −70° C. J Bacteriol. 1967;94:832–5. doi: 10.1128/jb.94.4.832-835.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiegeshaus EH, McMurray DN, Grover AA, Harding GE, Smith DW. Host–parasite relationships in experimental airborne tuberculosis. 3. Relevance of microbial enumeration to acquired resistance in guinea pigs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1970;102:422–9. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1970.102.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McMurray DN, Carlomagno MA, Mintzer CL, Tetzlaff CL. Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine fails to protect protein-deficient guinea pigs against respiratory challenge with virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1985;50:555–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.555-559.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buddle BM, deLisle GW, Pfeffer A, Aldwell FE. Immunological responses and protection against Mycobacterium bovis in calves vaccinated with a low dose of BCG. Vaccine. 1995;13:1123–30. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00055-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buddle BM, Parlane NA, Keen DL, Aldwell FE, Pollock JM, Lightbody K, Andersen P. Differentiation between Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated and M. bovis-infected cattle by using recombinant mycobacterial antigens. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1999;6:1–5. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.1.1-5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Estcourt MJ, Ramsay AJ, Brooks A, Thomson SA, Medveckzy CJ, Ramshaw IA. Prime-boost immunization generates a high frequency, high-avidity CD8 (+) cytotoxic T lymphocyte population. Int Immunol. 2002;14:31–7. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tange A, Denis O, Lambrecht B, Motte V, van den Berg T, Huygen K. Tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding Ag85A is immunogenic and protective when administered by intramuscular needle injection but not by epidermal gene gun bombardment. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3854–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3854-3860.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandt L, Feino Cunha J, Weinreich Olsen A, Chilima B, Hirsch P, Appelberg R, Andersen P. Failure of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine: some species of environmental mycobacteria block multiplication of BCG and induction of protective immunity to tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:672–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.70.2.672-678.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu CY, Kirman JR, Rotte MJ, et al. Distinct lineages of T (H) 1 cells have differential capacities for memory cell generation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:852–8. doi: 10.1038/ni832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang GZ, Balasubramanian V, Smith DW. The protective and allergenic potency of four BCG substrains in use in China determined in two animal models. Tubercle. 1988;69:283–91. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(88)90051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buddle BM, Wards BJ, Aldwell FE, Collins DM, de Lisle GW. Influence of sensitisation to environmental mycobacteria on subsequent vaccination against bovine tuberculosis. Vaccine. 2002;20:1126–33. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]