Abstract

The B lymphocyte subsets of X-chromosome-linked immune-deficient (XID) mice were examined by flow cytometric analyses of spleen and peritoneal cells. As shown in prior studies, young adult XID mice had reduced representation of the CD5+ (B-1a) subset in their peritoneal cavity. However, the CD11b+ (B-1b) B-cell subset was present and exhibited the IgMhi CD45lo CD23− phenotype characteristic of most B-1 cells. Although present at a lower frequency than that found in their normal counterparts, B-1b cells were evident in CBA/N and (XD2J)F1 male mice. With increasing age, B-1b cell number increased and in the oldest XID mice were present as B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. These results show that XID mice do have B-1 cells, particularly the B-1b subset.

Introduction

The X-chromosome-linked immune-deficiency (XID) of CBA/N mice is similar to that found in human X-linked agammaglobulinaemia (XLA).1 Both XLA and XID result from mutations in the gene for Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk), a member of the Tec family of kinases.2–7 The human disease, and somewhat milder murine form, are intrinsic to B lymphocytes and manifest primarily as defective humoral immunity.1,8 Wild type CBA/N mice, Btk-deficient mice, and mice deficient for the p85α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) linked to the Btk signal transduction pathway, have reduced serum antibody production, unresponsiveness to thymus-independent type 2 (TI-2) antigens, and defective terminal B-cell differentiation.1,7,9–14 The immunoglobulin isotype profile and antibody response phenotypes of these mice have been ascribed to a severe reduction in the B-1 B-cell subset.7,9,10,15

B lymphocyte subsets have been resolved based on function, anatomic location, and surface antigen expression.16–18 The B-1 subset, predominant in body cavities, notably the peritoneal cavity (PerC), has specificity for endogenous self-antigens and the carbohydrate antigens of microflora thus contributing to natural immunity by ‘spontaneous’ immunoglobulin M (IgM) production.16–21 Marginal zone (MZ) B cells, found in the spleen at the border of the red and white pulp, and B-1 B cells are responsible for rapid responses to TI antigens.22 B-2 (follicular) B cells, predominant in conventional lymphoid tissue such as spleen or lymph node, respond to exogenous, thymus-dependent (protein) antigens and include precursors for memory B cells.18,21,23 Each B-cell subset expresses a distinctive set of membrane antigens. B-2 B cells bear the CD45R[B220]hi IgMlo IgDhi CD21lo CD23+ CD43− phenotype, whereas MZ B cells express the reciprocal phenotype for these antigens and are CD9+.24 B-1 cells, initially defined by expression of the Ly-1 (CD5) T-cell marker, exhibit a CD45R[B220]lo IgMhi IgDlo CD23− CD43+ phenotype.16–18,25 Subsequent study revealed PerC B cells lacking CD5 yet expressing antigens distinctive of B-1 cells and led to the designation of B-1a (CD5+) and B-1b (CD5−) subsets.23 B-1b cells express CD11b (C3 or Mac-1) as a signature marker.16–18,23,26 B-1 B-cell subset research has focused upon the B-1a subset, including all of the studies of B cell biology in XID, Btk-deficient, and PI3K p85α-deficient mice.7,9,10,15–18

Recent studies have shown that CD11b expression best defines B-1 B cells in several strains of mice.27,28 As B-1 B cells are essential for innate immunity, we felt that the B-1 B-cell phenotype of XID mice should be revisited using this marker.19–21 In this report we show that B-1b cells are present in XID mice; B-1a cells, when present, are found at a lower frequency. These observations are discussed with respect to the roles of microenvironments and antigen-selective pressure in the persistence of B-cell subsets.

Materials and methods

Mice

Male and female BALB.xid (XID), BALB/c, C.B-17, and (BALB.xid X DBA/2 J [XD2J])F1 mice, bred and maintained at Rider University, were studied between the ages of 0·5 and 27 months. CBA/CaHN (CBA/N) mice were obtained from the Jackson laboratory. All mice were handled in accord with NIH, Animal Welfare Act, and Rider University IACUC guidelines.

Immunization

Groups (n = 9–25) of age- and sex-matched BALB.xid and BALB/c mice were injected intravenously with 0·2 ml (10 µg) of fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)–dextran (Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) in physiological saline. Blood was collected via the retro-orbital plexus on day 5 postimmunization, the sera processed and immediately assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Preparation of cell suspensions

Spleen (SP) cell suspensions were obtained by gentle disruption of the organ between the frosted ends of sterile glass slides. Red blood cells were depleted by treatment by hypertonic lysis. PerC cells were collected by flushing the peritoneum with 10 ml of warm (37°) Hank's balanced salt solution supplemented with 3% fetal bovine serum. Viable cell counts were determined by Trypan blue exclusion.

Isotype- and antigen-specific ELISA

Serum IgM, IgG3, IgG1, IgG2a and IgA levels were determined by ELISA employing polyvinylchloride plates coated with affinity-purified, goat anti-mouse isotype-specific reagents (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL). Serum anti-FITC responses were determined on ELISA plates coated with FITC-labelled rabbit immunoglobulin as described previously.27 Rabbit anti-mouse F(ab′)2-specific horseradish peroxidase (HRPO) conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) in conjunction with o-phenylenediamine substrate was used for detection. Immunoglobulin isotype standards (Southern Biotechnology) were used to generate standard curves. The protocol and data analyses conducted were identical to those previously described.27,29

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometric analyses

SP and PerC cells were stained with FITC-labelled rat anti-mouse B220 (CD45R, RA3-6B2) monoclonal antibody (mAb), mouse anti-mouse IgH-6a mAb (IgMa, DS-1), or affinity-purified goat anti-mouse IgM (Southern Biotechnology) concurrent with one of the following phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled rat anti-mouse mAbs: anti-Mac-1 (CD11b, M1/70), anti-FcεR (CD23, B3B4). PE-labelled anti-CD45R was combined with FITC-labelled anti-FcγIII/II receptor(CD16/32, 2.4G2). In 3-colour analyses, cychrome-labelled rat antimouse Ly-1 (CD5, 53–7·3) mAb was employed. Isotype- and fluorochrome-matched, non-specific mAb controls were employed to establish gates. All mAbs were obtained from BD-Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The percentage of lymphocytes (10 000 events were collected) expressing these antigens were determined via multiparameter flow cytometric analyses on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) by forward scatter (FSC)/side scatter (SSC) gating of the lymphocyte population using CellQuest software. Age-matched normal (BALB/c, C.B-17 (XD2J)F1 female) mice were included in all staining experiments.

Statistical analyses

Data sets were compared using the Student's t-test with P < 0·05 considered significant.

Results

Presence of B-1b cells in the peritoneal cavity of XID mice

With the exception of two papers15,30 prior studies of B-cell subset composition report a lack of B-1a B cells in XID mice.7,9,10,16 Considering that these studies did not test for the presence of B-1b cells, that mice expressing xid have some natural antibody production, that XID mice respond to TI-1 antigens, and that XID mice have IgMhi B cells, we reasoned that the B-cell subset composition of these mice should be revisited. Flow cytometry was employed to analyze the B cell subsets of young adult (2–8 months) BALB/c (normal) and age-matched xid-congenic BALB.xid (XID) mice.

B-cell size has been a fundamental criterion distinguishing B-1 (larger) and B-2 (smaller) cells.16 XID mice have predominately small lymphocytes in their SP and PerC; in contrast, normal mice have a greater proportion of larger cells in their PerC (Fig. 1a, b). However, like normal mice, XID mice have a greater percentage of large cells in their PerC relative to their SP (Fig. 1a, b). Analysis of CD45R (B220) expression by the large cells revealed the predominance of CD45Rhi (B-2 phenotype) B cells in the SP of normal mice and both SP and PerC of XID mice (M1 gate; Fig. 1c, d). In contrast, the majority of large B cells were CD45Rlo (B-1 phenotype) in the PerC of normal mice (M2 gate; Fig. 1d). XID mice also had a significant (27·4%) population of large, CD45Rlo B cells in their PerC. Analysis of IgM expression revealed that XID mice have large B cells that express very high levels of IgM, particularly in the PerC (Fig. 1e, f). The presence of large B cells in the PerC with an IgMhi, CD45Rlo phenotype in XID mice indicated that they have B-1 cells.

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analyses of CD45R (B220) and IgM expression by the large spleen and peritoneal cavity lymphocytes of XID (shaded histogram) and normal (open histogram) mice. The SP and PerC cells of age-matched BALB.xid and BALB/c mice were stained with PE-labelled CD45R and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis. Total lymphocytes were gated based on their FSC/SSC characteristics (66·9% and 37·3% of cells for XID SP and PerC; 83·2% and 39·0% of cells for normal SP and PerC). (a) (SP) and (b) (PerC) depict FSC analysis for all lymphocytes; the M1 marker and percentages shown demarcate the larger cells. (c) (SP) and (d) (PerC) represent analysis of CD45R expression by the large cells gated in (a) and (b); the M1 and M2 markers gate the CD45hi and CD45lo cells. (e) (SP) and (f) (PerC) represent analysis of IgM expression by the larger cells gated in (a) and (b); the M1 marker gates the IgM+ cells. The experiment shown is representative of five conducted. MCF = mean fluorescence channel for gated cells.

The levels of expression of multiple cell surface antigens define the B-1 subset with the leucocyte common antigen (CD45R [B220]) and the FcɛR (CD23) being two of the least controversial.16–18,23,31 Combining these markers with other B-cell specific reagents, most commonly anti-IgM, is necessary for subset resolution. Analyses of the coexpression of CD45R and CD16/32, the FcγIII/II receptor on B cells and macrophages32 and coexpression of CD23 with IgM were conducted to assess B-cell subset composition in XID and normal mice. Both XID and normal mice had greater numbers of CD45Rlo/CD16/32hi (B-1) cells in the PerC relative to the SP, where the CD45Rhi/CD16/32lo (B-2 phenotype) subset was predominant in both strains of mice (Fig. 2a, b, e, f). With the exception of B-2 cells in the PerC (Fig. 2e, R2 gate), normal mice had greater representation of each B-cell subset in these tissues. Thus, based on these marker combinations, XID mice have peritoneal B-1 B cells.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD45R/CD16/32 and CD23/IgM expression by the SP and PerC lymphocytes of XID and normal mice. The SP (a–d) and PerC (e–h) cells of age-matched BALB.xid (a,c,e,g) and BALB/c (b,d,f,h) mice were stained with PE-labelled CD45R and FITC-labelled CD16/32 (a, b, e, f) or PE-labelled CD23 and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM (c, d, g, h) and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The experiment shown is representative of four conducted.

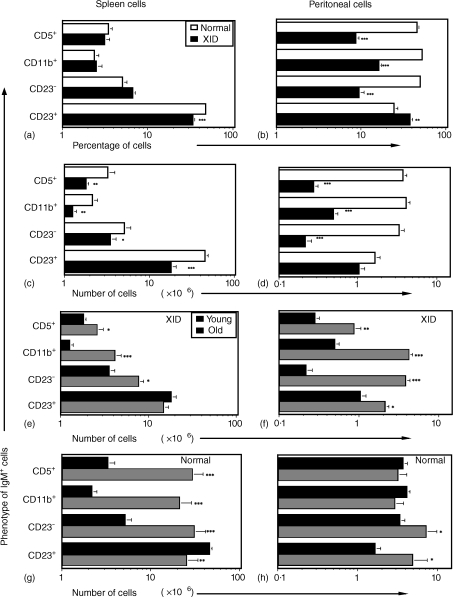

Although expression of CD5 initially defined the B-1 B-cell subset, subsequent work revealed B cells lacking this antigen yet expressing markers characteristic of B-1 cells.16–18 This ‘sister’ population became known as the B-1b subset, distinguished by expression of Mac-1 (CD11b).23 Mice expressing xid, in most7,9,10,16 but not all reports15,30 lack B-1 B cells as defined by CD5 expression (B-1a subset). Because assessment of Mac-1 expression by xid B cells has not been done, we tested for coexpression of this marker, as well as CD5, with IgM or CD45R on the SP and PerC cells of XID and normal mice. The data show that XID mice have B-1b cells in their PerC (Fig. 3g, o); B-1a cells were present at a much lower frequency (Fig. 3c, k). The percentage of B-1a and B-1b cells in the SP were not markedly different between normal and XID mice (Fig. 3a, e, i, m versus Fig. 3b, f, j, n). Similar results were obtained whether CD5-specific mAbs were coupled with the PE, FITC, or cychrome fluorochromes (data not shown). Compiled data, comparing multiple (n = 10–48) young (2–8 months) normal and XID mice, revealed no difference in the percentage of splenic IgM+ CD23− (B-1 and MZ) B cells including the B-1a (CD5+) and B-1b (CD11b+) subsets; there was a greater percentage of IgM+ CD23+ (B-2) B cells in normal mice (Fig. 4a). Reflecting the lower total lymphocyte number in XID versus normal mice (56·8 ± 4·8 [XID] versus 93·6 ± 5·2 [normal] × 106 SP cells [n = 10]) however, there were greater numbers of all of these subsets in the SP of normal mice (Fig. 4c). Compiled data for PerC cells from the same mice revealed greater percentages and numbers of IgM+ CD23− cells and both the B-1a and B-1b subsets in normal mice (Fig. 4b, d). The greater percentage of IgM+ CD23+ (B-2) cells in XID mice (Fig. 4b) resulted in their having total numbers of these cells similar to those found in normal mice (Fig. 4d). As with the SP, these data reflect lower PerC lymphocyte numbers in XID versus normal mice (3·1 ± 0·3 [XID] versus 8·0 ± 0·7 [normal] × 106 PerC cells [n = 26–48]). Overall, these data illustrate that, based on multiple phenotypic criteria, XID mice have B-1 cells, predominantly the B-1b subset, in their peritoneum.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD45R/CD5, CD45R/CD11b, CD5/IgM, and CD11b/IgM expression by the SP and PerC lymphocytes of XID and normal mice. The SP (a, b, e, f, i, j, m, n) and PerC (c, d, g, h, k, l, o, p) cells of age-matched (8 months) BALB.xid (a, c, e, g, i, k, m, o) and BALB/c (b, d, f, h, j, l, n, p) mice were stained with PE-labelled CD45R (a–h) and cychrome-labelled CD5 (a–d) and FITC-labelled CD11b (e–h) or FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM (i–p) and cychrome-labelled CD5 (i–l) and PE-labelled CD11b IgM (m–p) and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The experiment shown is representative of 12 conducted.

Figure 4.

Compilation of flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD5/IgM, CD11b/IgM, and CD23/IgM expression by the SP and PerC lymphocytes of XID and normal mice. Data are presented as the average percentage (a, b) or average number (c–h) of cells ± SEM bearing these markers in the SP (a, c, e, g) or PerC (b, d, f, h) of BALB/c (‘Normal’ a–d, open bars) or BALB.xid (‘XID’ a–d, filled bars) mice 1–8 months (a–d) of age. (e–h) Comparison of young (1–8 months, dotted bars) and old (17+ months, striped bars) normal (g, h) and XID mice (e, f). 15–72 mice were studied for each group. Asterisks indicate significance testing comparing cells from normal versus XID mice (a–d) or cells from young versus old mice (e–h) where * P < 0·05; **P < 0·005; *** P < 0·0005.

B-cell subset composition of ageing XID mice

Most murine research focuses upon mice less than 4 months of age, yet the average lifespan of the most common strains surpasses 20 months.33 This emphasis upon young adults misses changes in immunobiology concurrent with maturation. A hallmark of B-1 cells is that their number increases with ageing leading to B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (B CLL) in old mice.34,35 SP and PerC cells from ageing XID and normal mice were subjected to subset analyses to determine if B-1 cells increase in number with ageing.

Compiled data show that, with ageing, the number of both B-1a and B-1b cells increased in the SP and PerC of XID mice (Fig. 4e, f) and the SP of normal mice (Fig. 4g). B-1 B-cell numbers did not increase significantly in the PerC of normal mice (Fig. 4h). Representative B CLL profiles are shown in Fig. 5. As for B-1 cells in young mice, CD11b expression best defined the B CLL found in old XID mice (Fig. 5c versus Fig. 5g). In summary, these data show that, with ageing, the B-1 B cells of XID mice increase in number.

Figure 5.

Flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD11b/IgM, CD5/IgM, and CD23/IgM expression by the SP and PerC lymphocytes of old XID and normal mice. The SP (a, b, e, f, i, j) and PerC (c, d, g, h, k, l) cells of old BALB.xid (24 months; a, c, e, g, i, k) and BALB/c (22 months; b, d, f, h, j, l) mice were stained with PE-labelled CD11b and cychrome-labelled CD5 and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM (a–h) or PE-labelled CD23 and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM (i–l) and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The experiment shown is representative of 12 conducted.

Humoral immunity in ageing XID mice

Mice with xid as well as p85α- and btk-deficient mice have reduced serum IgM and IgG3 production and fail to respond to TI-2 antigens.7,9–12 These phenotypes have been attributed to a lack of B-1 cells, which are responsible for natural antibody production.16 As B-1b cells were found in XID mice and their number increased with age, we tested natural antibody production and TI-2 responsiveness in older XID mice to see if these deficiencies changed with ageing. Production of each antibody isotype increased with ageing, with that of IgM and IgG3 being the greatest (Fig. 6a–e). However, the level of these isotypes remained below normal. Furthermore, there was no recovery of the TI-2 response in older mice (Fig. 6f). These data illustrate that the humoral defects noted in young XID mice are maintained with ageing.

Figure 6.

Humoral immunity in ageing XID mice. Serum IgM, IgG3, IgG1, IgG2a and IgA levels (a–e) in ageing XID mice were determined by ELISA. The bold, solid line is an exponential curve fit for all points tested. The horizontal dotted line is the average serum immunoglobulin level (µg/ml) found in 4–8-month-old-normal mice (IgM = 2725, IgG3 = 281, IgG1 = 1539, IgG2a = 232, and IgA = 129 µg/ml; [n = 8]). Serum TI-2 response of young and old XID mice (f) determined by ELISA. Old XID = 20·4 ± 0·6 months (range = 15–24 months; n = 25); young XID = 3·4 ± 0·2 months (range = 3–4 months; n = 9); normal mice = 6·9.4 ± 0·4 months (range = 6–8 months; n = 9).

B-1 B cells in CBA/N and (XD2J)F1 male mice

BALB/c and BALB/c-congenic strains have been reported to have elevated numbers of B-1a cells when compared with other strains of mice.16 Although, we have shown that BALB.xid mice have B-1b cells, we were obligated to test B-1 cell representation in other strains expressing xid. Therefore, the prototype strain for xid, CBA/CaHN (CBA/N) mice, was tested. The male and female progeny of crosses between BALB.xid and DBA/2 J mice ([XD2J]F1) were also tested to provide a direct comparison of B-1-cell subset composition in xid (male) versus normal (female) littermates. CBA/N and certain DBA/2 strains have been reported to have no detectable Ly-1 B (B-1a) cells in their PerC.16

The data show that CBA/N mice have B-1 cells in their PerC, again best defined by CD11b expression (Fig. 7a versus Fig. 7d). Likewise (XD2J)F1 male (xid) mice have B-1b cells, albeit at reduced frequencies relative to their, age-matched, normal littermates. Compiled data comparing the PerC cells of CBA/N and BALB.xid mice revealed a lower percentage of B-1a cells in CBA/N mice, however, the total number of these cells and all of the other subsets tested, revealed no significant difference in B cell subset composition between these strains (Fig. 8).

Figure 7.

Flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD11b/IgM, CD5/IgM, and CD23/IgM expression by the PerC lymphocytes of XID and normal mice. The PerC cells of CBA/N (a, d, g) (XD2J)F1 female (normal), and (XD2J)F1 male (XID) mice were stained with PE-labelled CD11b and cychrome-labelled CD5 and FITC-labelled goat anti-mouse IgM (a–f) or PE-labelled CD23 and FITC-labelled goat antimouse IgM (g–i) and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The experiment shown is representative of four conducted

Figure 8.

Compilation of flow cytometric analyses of correlated CD5/IgM, CD11b/IgM, and CD23/IgM expression by the PerC lymphocytes of CBA/N and BALB.xid mice. Data are presented as the average percentage (a) or average number of cells (b) ± SEM bearing these markers in the PerC of CBA/N (striped bars) or BALB.xid (filled bars) mice 4–6 months of age. 6–12 mice were studied for each group. * = P < 0·05.

In summary, in all three strains expressing xid, including the strain that served as the original source of xid, B-1b cells are evident in the PerC.

Discussion

Mice expressing xid or related genetic deficiencies (p85α- or Btk-deficiency) exhibit B-cell defects that have been ascribed to the absence of B-1 cells, specifically the CD5+ (B-1a) subset; the presence of the CDllb+ (B-1b) subset has not been assessed. This B-cell deficiency in XID mice however, is incomplete as these mice survive in conventional vivaria, make some natural antibody, and respond to some carbohydrate antigens (TI-1). This discrepancy led to a reassessment of the B-cell subset composition of XID mice. The data reported here show that B-1b cells are present in XID mice and that their numbers increase with ageing. These results are consistent with studies indicating that B-1 cell specificity for self antigens plays a role in their persistence and are informative regarding the B CLL generation inherent to normal ageing.34–39

That B-1b cells were not reported in prior studies of XID mice is likely a reflection of the focus placed upon the use of CD5 as the definitive marker for this B-cell subset. Two prior studies reported the presence of CD5+ B cells in mice expressing xid.15,30 Neither of these studies monitored CD11b expression on B-cell subsets. Recent research indicates that this marker is definitive for the B-1 cells found in certain strains of mice.27,28 To ensure a complete analysis of B-cell subset composition, future studies will need to include CD11b in the growing panel of reagents employed to define these cells.17 Consistent with prior studies, XID PerC B-1 cells were found to express the leukosialin-specific marker CD43 and the tetraspanin-specific marker CD924,30,40 (data not shown). Thus, by all criteria currently employed to define B-1 cells, XID mice harbour this important subset of B lymphocytes.

Why are B-1b cells the predominant B-1 B cell subset in XID mice? Most distinctions reported for B-1b cells are not particularly revealing with respect to the findings described here.41 However, evidence that B-1a and B-1b subsets differ in their appearance during development may be informative, particularly since xid B cells are noteable for their delayed B-cell maturation.1 B-1b cells appear after B-1a cells during normal development and can be derived from the bone marrow of adult mice.42,43 The development of B-1a cells may be more severely impacted by xid, permitting the later development and predominance of the B-1b subset. Defective signalling which impairs CD5 expression may be responsible;44 CD11b expression may not be significantly impacted by xid. Alternatively, xid B cells may not be wholly comparable to B cells of normal mice.45,46 The observations reported here are not directly pertinent to p85α- and Btk-deficient mice as each of these mutants has a distinctive phenotype and were not included in this study.

If B-1 cells are responsible for TI-2 responsiveness and natural antibody production and B-1b cells are present in XID mice, why does this strain lack a TI-2 response and have reduced serum IgM and IgG3 production? It is unlikely that the B-1a subset is solely responsible for these functions. Although xid permits some B-1b-cell development, it likely impairs the signal transduction required to respond to exogenous and endogenous (self) antigens of the TI-2 class.7,47 Splenic MZ B cells share several properties, and work, with B-1 cells in TI-2 responses and Btk has been shown to abrogate MZ B cell development.22,48 Thus, the presence of B-1b cells does not necessarily confer TI-2 responsiveness and complete natural antibody production. Although natural antibodies are produced by a B-1b-like, SP B-cell population49 the general reduction in IgM and IgG3 seen in XID mice is likely attributable to defective signalling in, and the subsequent apoptotic death of, clones bearing self-antigen reactive specificities.50 Still, xid B-1b cells are being selected for survival, persistence, and expansion with ageing, albeit at a lower frequency. Thus, as in normal mice, VH specificity, endogenous antigens, and lymphoid microenvironments likely play essential roles in xid B-1-cell development and the increased numbers of these cells that is seen with normal ageing.37,38,51

In summary, although xid impairs B-1a cell development, mice expressing this mutation have B-1b cells in their peritoneal cavity. The study of xid B cells should provide further insight into the relationships between the B-1a, B-1b, and B-2 subsets.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH AREA programme (R15 CA77814-01 and R15 AG19631-01). We are indebted to Rebecca Crescitelli and Diana Gonzalez for outstanding maintenance of the mouse vivaria.

Abbreviations

- B CLL

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

- Btk

Bruton's tyrosine kinase

- MZ

marginal zone

- PerC

peritoneal cavity

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- SCID

severe combined immune deficiency

- SP

spleen

- TI-2

thymus-independent type 2

- (XD2J)

(BALB.xid X DBA/2J)

- xid and XID

X-chromosome-linked immune-deficient

References

- Scher I. The CBA/N mouse strain: an experimental model illustrating the influence of X chromosome on immunity. Adv Immunol. 1982;33:1–71. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60834-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruton O. Agammaglobulinemia. Pediatrics. 1952;9:722–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada S, Saffran D, Rawlings D, et al. Deficient expression of a B cell cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Cell. 1993;72:279–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90667-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetrie D, Vorechovsky I, Sideras P, et al. The gene involved in X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA) is a member of the src family of protein-tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1993;361:226–33. doi: 10.1038/361226a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings D, Saffran D, Tsukada S, et al. Mutations of a unique region of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in immunodeficient XID mice. Science. 1993;261:358–61. doi: 10.1126/science.8332901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Sideras P, Vorechovsky I, Smith C, Chapman V, Paul W. A missense mutation in the X-linked agammaglobulinemia gene colocalizes with the mouse X-linked immunodeficiency gene. Science. 1993;261:355–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8332900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan W, Alt F, Gerstein R, et al. Defective B cell development and function in Btk-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:283–99. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley M, Brown P, Pickard A, Buckley R, Miller D, Raskind W, Singer J, Fialkow P. Expression of the gene defect in X linked agammaglobulinemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:564–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198608283150907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Terauchi Y, Fujiwara M, Aizawa S, Yazaki Y, Kadowaki T, Koyasu S. Xid-like immunodeficiency in mice with disruption of the p85α subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Science. 1999;283:390–2. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruman D, Snapper S, Yballe C, Davidson LYuJ, Alt F, Cantley L. Impaired B cell development and proliferation in absence of phosphoinositide 3-kinase p85α. Science. 1999;283:393–6. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter R, Nahm M, Stein K, Slack J, Zitron I, Paul W, Davie J. Immunoglobulin subclass-specific immunodeficiency in mice with an X-linked B-lymphocyte defect. J Exp Med. 1979;149:993–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.149.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsbaugh D, Hansen C, Prescott B, Stashak P, Barthold D, Baker P. Genetic control of the antibody response to Type III pneumococcal polysaccharides in mice. I. Evidence that an X-linked gene plays a decisive role in determining responsiveness. J Exp Med. 1972;136:931–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.4.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher I, Steinberg A, Berning A, Paul W. X-linked B lymphocyte immune defect in CBA/N mice. II. Studies of the mechanisms underlying the immune defect. J Exp Med. 1975;142:637–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Hayakawa K, Haaijman J, Herzenberg L. B-cell subpopulations identified by two-color fluorescence analysis using a dual-laser FACS. Nature. 1982;297:589–91. doi: 10.1038/297589a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, Hardy R, Parks D, Herzenberg L. The ‘LY-1 B’ cell subpopulation in normal, immunodefective, and autoimmune mice. J Exp Med. 1983;157:202–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.1.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzenberg L, Stall A, Lalor P, Sidman C, Moore W, Parks D, Herzenberg L. The Ly-1 B cell lineage. Immunol Rev. 1986;93:81–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1986.tb01503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Hayakawa K. B cell development pathways. Ann Rev Immunol. 2001;19:595–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berland R, Wortis H. Origins and functions of B-1 cells with notes on the role of CD5. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:253–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsenbein A, Fehr T, Lutz C, Suter M, Brombacher F, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R. Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science. 1999;286:2156–9. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson A, Gatto D, Sainsbury E, Harriman G, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel R. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science. 2000;288:2222–6. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarth N, Herman O, Jager G, Brown L, Herzenberg L, Chen J. B-1 and B-2 cell-derived immunoglobulin M antibodies are nonredundant components of the protective response to influenza virus infection. J Exp Med. 2000;192:271–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Oliver A, Kearney J. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14:617–29. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor A. A new nomenclature for B cells. Immunol Today. 1991;12:389. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90135-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won W-J, Kearney J. CD9 is a unique marker for marginal zone B cells, B1 cells, and plasma cells in mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:5605–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier L, Warner N, Ledbetter J, Herzenberg L. Expression of Lyt-1 antigen on certain murine B cell lymphomas. J Exp Med. 1981;153:998–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.4.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De la Hera A, A-Mon M, Sanchez-Madrid F, Martinez AC, Durantez A. Co-expression of Mac-1 and p150,95 on CD5+ B cells. Structural and functional characterization in a human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1131–4. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkley K, Chiasson R, Prior T, Riggs J. Age-dependent increase of peritoneal B-1b cells in SCID mice. Immunology. 2002;105:196–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell K, Campo M, Chiasson R, Duffy K, Riggs J. B-1 B cell subset composition of DBA/2J mice. Immunobiology. 2002;205:303–13. doi: 10.1078/0171-2985-00133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior L, Pierson S, Woodland R, Riggs J. Rapid restoration of B cell function in XID mice by intravenous transfer of peritoneal cavity B cells. Immunology. 1994;83:180–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S, Arnold L. B-1 cell development: evidence for an uncommitted immunoglobulin (Ig) M+ B cell precursor in B-1 cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1325–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldschmidt T, Snapp K, Foy T, Tygrett L, Carpenter C. B-cell subsets defined by the FcεR. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;651:84–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unkeless J. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. J Exp Med. 1979;150:580–96. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.3.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green E the Staff of The Jackson Laboratory. Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. New York: Dover Publications; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Stall A, Farinas M, Tarlinton D, Lalor P, Herzenberg L, Strober S, Herzenberg L. Ly-1 B cell-clones similar to human chronic lymphocytic leukemias routinely develop in older normal mice and young autoimmune (New Zealand Black-related) animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7312–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMaoult J, Delassus S, Dyall R, Nikolic-Zugic J, Kourilsky P, Weksler M. Clonal expansions of B lymphocytes in old mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:3866–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam K-P, Rajewsky K. B cell antigen receptor specificity and surface density together determine B-1 versus B-2 cell development. J Exp Med. 1999;190:471–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, Asano M, Shinton S, Gui M, Allman D, Stewart C, Silver J, Hardy R. Positive selection of natural autoreactive B cells. Science. 1999;285:113–6. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumley M, Dal Porto J, Kawaguchi S, Cambier J, Nemazee D, Hardy R. A VH11Vk9 B cell antigen receptor drives generation of CD5+ B cells both in vivo and in vitro. J Immunol. 2000;164:4586–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Horkko S, Chang M-K, Curtiss L, Palinski W, Silverman G, Witztum J. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S, Kantor A, Stall A. CD43 (S7) expression identifies peripheral B cell subsets. J Immunol. 1994;153:5503–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein TL. Cutting edge commentary: two B-1 or not to be one. J Immunol. 2002;168:4257–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A, Lehuen A, Kearney J. Immunofluorescence analysis of B-1 cell ontogeny in the mouse. Int Immunol. 1994;6:355–61. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor A, Stall A, Adams S, Herzenberg L, Herzenberg L. Differential development of progenitor activity for three B-cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:3320–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortis H, Teutsch M, Higer M, Zhebg J, Parker D. B-cell activation by crosslinking of surface IgM or ligation of CD40 involves alternative signal pathways and results in different B-cell phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3348–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosier D. Are xid B lymphocytes representative of any normal population? A commentary. J Mol Cell Immunol. 1985;2:70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Hayakawa K, Parks D, Herzenberg L. Demonstration of B-cell maturation in X-linked immunodeficient mice by simultaneous three-colour immunofluorescence. Nature. 1983;306:270–2. doi: 10.1038/306270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinuesa C, Sunners Y, Pongracz J, Ball J, Toellner K, Taylor D, MacLennan I, Cook M. Tracking the response of Xid B cells in vivo: TI-2 antigen induces migration and proliferation but Btk is essential for terminal differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1340–50. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200105)31:5<1340::AID-IMMU1340>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin F, Kearney J. Positive selection from newly formed to marginal zone B cells depends on the rate of clonal production, CD19, and btk. Immunity. 2000;12:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohdan H, Swenson K, Kruger Gray H, Yang Y-G, Xu Y, Thall A, Sykes M. Mac-1-negative B-1b phenotype of natural antibody-producing cells, including those responding to Gal1α,3Gal epitopes in α 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2000;165:5518–29. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodland R, Schmidt M, Korsmeyer S, Gravel K. Regulation of B cell survival in xid mice by the proto-oncogene bcl-2. J Immunol. 1996;156:2143–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumley M, Dal Porto J, Cambier J. The unique antigen receptor signaling phenotype of B-1 cells is influenced by locale but induced by antigen. J Immunol. 2002;169:1735–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]