Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells play an important role in the first line of defence against viral infections. We have shown earlier that exposure of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to viruses results in rapid up-regulation of NK cell activity via interleukin-15 (IL-15) induction, and that this mechanism curtails viral infection in vitro. By using Candida albicans, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, we now show here that exposure of PBMC to fungi and bacteria also results in an immediate increase of NK cytotoxicity. Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction and Western blot analyses as well as the use of antibodies against different cytokines revealed that IL-15 induction played a predominant role in this NK activation. These results indicate that IL-15 is also involved in the innate immune response against fungal and bacterial agents.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells constitute a critical component of the innate immune response and represent first line of defence to infection and malignancy. They are important mediators of innate resistance against viral infections and transformed cells.1,2 Such immunoprotection is due to their ability to exert a cytotoxic activity against infected and tumor cells without prior sensitization or major histocompatibility complex (MHC) restriction. In addition, there is increasing evidence that NK cells also play a major role in the early defence against bacterial and fungal infections.2–4 NK cells have been reported to be directly bactericidal and to lyse bacterial-infected cells.5,6 Furthermore, these immune cells may also control bacterial infections by producing cytokines that activate the phagocytic cells to engulf and degrade the bacteria.7,8 Moreover, it has been reported that NK cells are also able to inhibit the growth of fungus.9,10 Several studies showed that granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ), secreted by activated NK cells, up-regulate the fungicidal activity of phagocytic cells resulting in the growth inhibition of these agents.3,11,12 This antifungal immunity, mediated by NK cells via secretion of cytokines and then activation of phagocytic cells, have been shown to represent antifungal defence in vitro3 and this mechanism may also occur in vivo.

Viral, bacterial and fungal infections are often associated with an increase in NK cell cytocidal activity which may be mediated by cytokines.13–15 Among the latter, interleukin-15 (IL-15) is certainly a potent up-regulator of NK cell cytotoxicity;16 it is a relatively recently discovered cytokine with many immunologic activities that overlap with those of IL-2.16 Being a member of the four α-helix bundle family of cytokines, IL-15 shares with IL-2 the ability to induce the proliferation of T-cell lines.17 Both cytokines generate cytotoxic effectors, including lymphokine-activated killer cells.16,17 IL-15 is required for the maintenance and renewal of viral specific CD8+ T cells.18,19 Overexpression of IL-15 in vivo enhances antitumour activity against malignant melanoma through augmented NK activity and cytotoxic T-cell response.20 The human IL-15 gene is constitutively expressed in several human tissues.21,22 In peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), IL-15 is mainly produced by monocytes, whereas IL-2 is expressed only in activated T cells.23,24 Furthermore, several studies have shown the essential involvement of IL-15 in the development of NK cells.25–27 In fact, IL-15 plays a major role in the differentiation of NK cells from their progenitors as well as in NK survival and NK functions.17

We had postulated that IL-15 may play an important role during the innate response to infection. Indeed, previous studies in this laboratory have shown that exposure of human PBMC to different unrelated viruses resulted in a rapid increase of NK activity of these PBMC via IL-15 induction.28,29 This enhanced NK activity was shown to play a role in the control of these infections in vitro.30,31 Therefore, we undertook a study to determine whether fungal and bacterial agents also have the capacity to enhance NK cell cytotoxic activity via up-regulation of IL-15 gene expression. For this purpose, we used Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli in this study. These are ubiquitous and opportunistic human pathogens which can cause significant diseases, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, e.g. acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Our results show that human PBMC also respond via up-regulation of IL-15 expression to these non-viral pathogens. This underscores the role of IL-15 induction as an early signal of the innate immune response to pathogens of diverse origin.

Materials and methods

PBMC isolation

PBMC from healthy donors were prepared (after their informed and written consent, following the approval of our research by this Center's Ethics Committee) by centrifugation of heparinized venous blood over Ficoll-paque (Pharmacia, Montreal, Canada) gradients and collected as previously described.29 The separated cells were washed and cultured in complete medium: RPMI-1640 culture medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 20 µg/ml streptomycin, and 1 µg/ml gentamicin.

Cell lines and virus preparation

K562, a human erythroleukemic cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA); these cells were cultured in complete medium. Human herpesvirus-6 (HHV-6, GS strain) was propagated in HSB-2 cells as described earlier.29 The supernatant from these virus-infected cells was collected and used as a source of this virus (as positive control) as described.29

Preparation of Candida and bacteria

Pathogenic Candida albicans (obtained from Dr Louis de Repentigny, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, University of Montreal) was cultured in YPD broth (Difco Laboratories; Detroit, MI) for 36 hr at 37° with aeration on a shaker and then washed three times with sterile distilled water. The Candida pellet, harvested by centrifugation (10 000 g for 10 min), was resuspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and heated for 1 hr at 100°.32 A sample of this preparation was mixed with trypan blue and counted on a haemocytometer. The concentration was adjusted with sterile PBS to 6 × 107/ml and stored at 4°. The heat-inactivated C. albicans did not grow when tested in YPD broth.

Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli (obtained from Dr Céline Laferrière, Department of Microbiology & Immunology, Ste-Justine Hospital) were grown in Luria Broth base (GibcoBRL, Paisley, UK) for 36 hr at 37° with aeration on a shaker. Bacteria were washed three times with sterile PBS. The bacterial pellets (obtained by centrifugation at 10 000 g for 30 min) were resuspended in sterile PBS, and exposed to UV light for 2 hr. To verify the inactivation of these bacteria, UV-inactivated S. aureus and E. coli were inoculated in Luria Broth base and incubated at 37° for 36 hr on a shaker. Bacterial cell counts were done (prior to their inactivation) by serial dilution on agar plates as described.33 The bacterial concentration was adjusted with PBS to 1 × 108/ml.

It is important to note here that preliminary experiments to compare the ability of live as well as inactivated pathogens' preparations to induce IL-15 and NK cell activation had produced similar results (data not shown). Therefore, all the experiments described below were carried out using heat-inactivated Candida and UV-inactivated bacterial preparations.

Cell treatments

Fresh PBMC (1 × 106 cells) were infected with HHV-6 for 2 hr at 37° as described earlier.29 Unabsorbed virus was removed by washing three times with RPMI-1640 medium and the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of the complete medium. Heat-inactivated C. albicans (C. albicans to PBMC ratio 1 : 1), 100 µl of UV-inactivated E. coli or S. aureus were directly added to PBMC (1 × 106 cells), and resuspended in 1 ml of the complete medium. The PBMC were incubated at 37°, and at different time points, treated and untreated PBMC were collected and adjusted to 4 × 106 cells/ml. This cell suspension (50 µl) was then added to 104 cells 15Cr-labelled K562 cells and their NK activity was determined as described above. The NK activities of PBMC were also tested in the presence of anti-IL-15 antibodies (10 µg/ml; see below). Different ratios of microbes to PBMC were tested. Optimal increase of NK activity was observed when a ratio 1 : 1 (1 C. albicans to 1 PBMC), 100 µl of UV-inactivated E. coli, 100 µl UV-inactivated S. aureus were added to 1 × 106 cells (PBMC). Therefore, these ratios were applied to all experiments.

Cytokine-specific antibodies

Neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) to human IL-15 (M112) was a gift from Immunex (Seattle, WA). Neutralizing mAbs to human IL-2, IL-12 and TNF-α were all purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All these antibodies were used at a concentration of 10 µg/ml as described.34 IFN-α-neutralizing mAb was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), and was used in the assay at a concentration that neutralizes 3000 U/ml.

NK cell cytotoxicity assay

NK cell activity was measured by using a standard 51Cr-release assay as described previously.29 Briefly, K562 target cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were labelled by incubation with 100 µCi of sodium chromate (51Cr; Mandel, Montreal, Canada) for 1 hr at 37°. After four washes with complete medium, the radiolabelled cells were counted and resuspended at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/ml in complete medium. One hundred µl of the labelled K562 cells were added into the wells of a 96 well plate with V-shaped bottom and mixed with 50 µl of PBMC (4 × 106 cells/ml) from healthy donors at an effector to target ratio of 20 : 1 and then incubated for 16 hr at 37° in a CO2 incubator. After this incubation, 100 µl of cell-free supernatant was collected from each well and the radioactivity was then measured (as counts per minute, c.p.m.) using a gamma-counter (Wallac LKB; Turco, Finland). The percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated using the following formula: [(c.p.m. experimental − c.p.m. spontaneous)/(c.p.m. maximum − c.p.m. spontaneous)] × 100. All these experiments were done in triplicate, and the results are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent determinations. The spontaneous c.p.m. was determined by counting the radioactivity of the supernatant of the target cell suspensions, whereas the maximum c.p.m. was determined from the radioactivity of the 104 target cells lysed with Triton-X (100 µl). It should be noted here that a variation in percentage NK cytotoxicity is commonly observed between individual experiements as a result of the use of blood from different donors.

Western Blots

IL-15 protein expression by human PBMC was detected by Western blot analysis as described.35 Briefly, 15 × 106 cells were lysed in 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 6·8), 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) and sonicated for 15 s. By centrifugation (14 000 g for 30 min at 4°), the lysates were clarified and protein concentrations were determined by a commercial kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Eighty micrograms of the lysate proteins were resolved on 15% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and then electroblotted onto nylon membranes (Immobilon, Millipore, Bredford, MA). The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk powder in PBS and then incubated with IL-15 mAb (M112). After washing, blots were developed using alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated secondary antibody (anti-mouse immunoglobulin G; Promega, Madison, WI) and chromogenic substrates 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) with nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT; Promega). A concentration of 1 µg/ml of IL-15 mAb was used for the detection of IL-15 protein expression in the Western blots.

Analysis of IL-15 mRNA by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Freshly isolated PBMC (5 × 106 cells) were treated with different pathogens and at different time points (6, 12, 18, and 24 hr) post-treatment, cell pellets were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml of Trizol Reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The Trizol Reagent was used to extract total RNA from cells as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the method consisted of disrupting cells with the Trizol reagent, and extracting RNA from the mixture with chloroform. The total RNA was then treated with DNase and subjected to RT–PCR as previously described.27 Thirty µl of the PCR product were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide for the visualization of the cDNA and validated by Southern blots as described below.

Southern blot

The amplified cDNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) overnight by capillary transfer technique and cross-linked with UV. The membrane was prehybridized and hybridized for 6 hr and overnight, respectively, at 46° using a rapid-hyb buffer (Amersham Life Sciences, Arlington Heights, IL). The amplified cDNA was then probed with a 32P-labelled IL-15 probe (5′-ATGTCTTCATTTTGGGCTGTTTCAGTGCAG-3′)27 and 32P-labelled human β-actin cDNA excised by EcoRI restriction enzyme from the actin containing the 1·1-kb plasmid (Bluescript SK - ; ATCC). After hybridization, the blots were washed (30 min/wash) with 2xSSC/0·1%SDS solution twice and once with 0·2XSSC/0·1%SDS solution at 46°. The intensity of the probed products was measured using a phosphorimager (PhosphorImager SI; Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test and P ≤ 0·05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Enhancement of NK activity by different pathogens

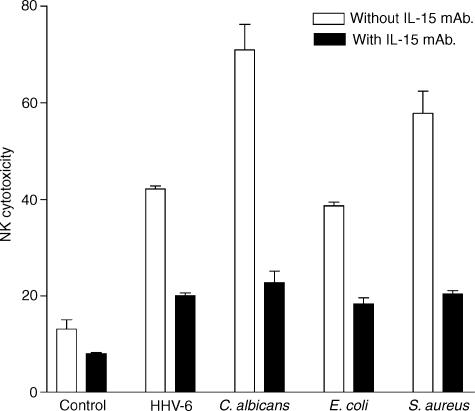

We first determined whether the exposure of human PBMC to different microbial pathogens affects the level of NK activity of these PBMC. For this purpose, we incubated PBMC of three healthy donors with HHV-6, E. coli, S. aureus or C. albicans for 24 hr. The NK cytotoxic activity of these PBMC was measured by the standard 51Cr release assay as described in Materials and Methods. The results show (Fig. 1) that all these pathogens increased significantly (P ≤ 0·05) the NK activity of human PBMC as measured 24 hr post-treatment. C. albicans induced the highest increase in cytotoxic activity in PBMC of three donors. Next (in decreasing order) were S. aureus HHV-6 and E. coli. These results represent fold increase of 2·8, 2·5, 4·1 and 5·6 in the NK activity following exposure of PBMC to HHV-6, E.coli, S. aureus and C. albicans, respectively. The up-regulation of NK activity induced by HHV-6 confirms previous work from this laboratory,27 and served as a positive control for measuring the effect of other three pathogens tested. We also found that there was no cytotoxic effect of these pathogens (live or inactivated) on K562 cells, i.e. when tested in the absence of PBMC (data not shown). Clearly, the capacity of pathogen-treated PBMC to increase their cytocidal (i.e. NK) activity, over two- to five-fold, indicates that a healthy host can mount a strong innate (NK) immune response against all these pathogens.

Figure 1.

Effect of different pathogens on enhancement of NK cytocidal activity in the presence or absence of anti-IL-15 mAb. PBMC, pre-exposed to each of the indicated pathogens, were incubated with or without IL-15 neutralizing mAb (10 µg/ml). After 24 hr incubation at 37°, PBMC were incubated with 51Cr-labelled K562 cells at an E : T ratio of 20 : 1 for 16 hr (see Materials and methods). The data shown are expressed as percentage of NK cytotoxicity and represent mean ± SEM of triplicate determination using PBMC from three donors. The isotype-matched control antibody (for the IL-15 neutralizing antibodies) was also tested, no decrease of NK activity was observed (data not shown)

Up-regulation of NK cell cytotoxicity by different pathogens via IL-15 induction

We next determined whether IL-15 was involved in this increase. To this end, an IL-15 neutralizing mAb (10 µg/ml) was added to PBMC culture during incubation (24 hr) with the pathogens and NK activity was then measured as described above. The results show that the presence of these neutralizing antibodies resulted in a striking decrease in NK activity for each pathogen, i.e. 2·8, 2·1, 2·7, and 2·5 fold for C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus and HHV-6, respectively (Fig. 1). Therefore, these data clearly illustrate that the enhancement of NK killing activity observed was mainly due to IL-15 induction.

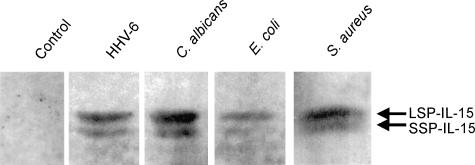

Expression of IL-15 protein by treated PBMC

We then proceeded to determine whether the levels of enhancement of NK activity by these pathogens used correlated with the IL-15 protein levels they induced. Thus, IL-15 protein expression was determined by Western blots following 24 hr exposure of human PBMC to C. albicans, HHV-6, E. coli and S. aureus. For allowing direct comparison of the effect of pathogens on IL-15 production, equal amounts of protein were loaded on the Western blots. In accord with the highest enhancement of NK activity observed for C. albicans, the latter induced the highest expression of IL-15 protein (the darkest bands), followed by other pathogens (Fig. 2). No band was observed in the untreated PBMC. Interestingly, we observed two bands migrating in close proximity on the gel for each sample. This result showed that IL-15 protein exists in the cell in two major isoforms. The IL-15 mAb (M112) used is known to recognize both these isoforms.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of IL-15 protein expression in PBMC treated with different pathogens. PBMC exposed to the indicated pathogens for 24 hr were lysed and run on 15% SDS–PAGE. After electroblotting onto nylon membrane, IL-15 mAb (M112) (1 µg/ml) was incubated with membrane to allow the specific binding of mAb to IL-15 protein on the membrane. The blots were developed using AP-conjugated anti-mouse, BCIP and NBT. The experiment was repeated with three donors and similar results were obtained each time (not shown). Uninfected PBMC (band 1), PBMC treated with HHV-6 (band 2), with C. albicans (band 3), with E. coli (band 4), and with S. aureus (band 5).

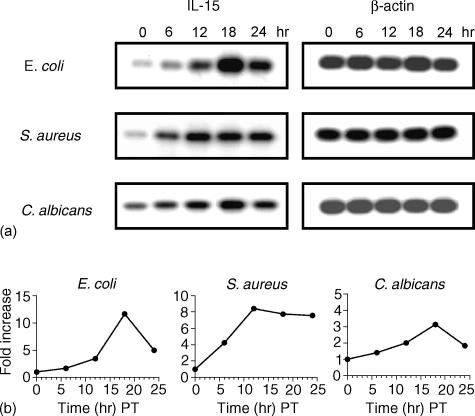

Kinetics of IL-15 mRNA expression

Because Western blot analysis clearly demonstrated an increase of IL-15 protein expression in PBMC treated with the different pathogens used, next we determined the level of IL-15 mRNA expression at different time points (i.e. 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 hr) in PBMC exposed to E. coli, S. aureus and C. albicans. Cells were lysed and mRNA levels were assessed by semiquantitative RT–PCR (Fig. 3a). IL-15 mRNA expression peaked at 18 hr post-treatment (PT) for most of the pathogens with some variation among the different pathogens. E. coli and C. albicans peaked at 18 hr PT, with a 11·7- and 3·1-fold increase, respectively, and S. aureus peaked at 12 hr PT, with a 8·4-fold increase. Moreover, the increase of IL-15 mRNA expression at 24 hr PT for E. coli, S. aureus and C. albicans was 5-, 7·6- and 1·8-fold, respectively (Fig. 3b). Compared to Western blot analysis (Fig. 2), this result shows a lack of correlation between mRNA levels and protein expression; this may suggest a differential regulation at the level of translation, trafficking and secretion of IL-15 protein.

Figure 3.

Kinetics of IL-15 mRNA expression in PBMC exposed to different pathogens. PBMC (5 × 106 cells) were exposed to different pathogens for various time periods (0, 6, 12, 18 and 24 hr). Cells were then lysed, and total RNA was extracted and measured. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed (RT) with oligo d(T), and IL-15 mRNA was amplified using PCR. Bands were detected following blotting on a nylon membrane as described in Materials and Methods. (a) IL-15 and β-actin bands obtained from PBMC treated and untreated with different pathogens at different time points. (b) Curves showing the increase (fold) of IL-15 mRNA levels in PBMC treated with different pathogens at different time points. Quantification of IL-15 mRNA was based on its expression relative to the amplified amount of β-actin mRNA.

Effect of neutralizing antibodies to IL-2, IL-12, IFN-α and TNF-α on the enhancement of NK activity following exposure to C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus and HHV-6

As shown previously, the neutralization of IL-15 by mAb resulted in a marked decrease in NK activity even below the level of the untreated (control) PBMC. It was still possible that IL-15 may have synergized with some other cytokines to effect this enhancement of the NK activity. Among the main cytokines which may enhance the NK activity include IL-2, IFN-α/γ, TNF-α/β, and IL-12. For the purpose of this experiment, antibodies against IL-2, IL-12, IFN-α, and TNF-α were used in the assay in order to verify possible implication of each of these cytokines in the enhancement of NK activity observed during the present experiments. Furthermore, anti-IL-15 mAb was also used in the assay. This approach allows a better view of the degree of contribution of these cytokines, compared to IL-15, to the enhancement of NK cytotoxic activity. PBMC treated with different pathogens were incubated with different cytokine-neutralizing antibodies for 24 hr (see Materials and methods). The data obtained are shown in Fig. 4. The results showed the contribution of IL-2, IL-12, IL-15 and IFN-α on the enhancement of NK activity of PBMC exposed to C. albicans (Fig. 4a). We observed the involvement of IL-12, IL-15, IFN-α and TNF-α on the NK killing of PBMC treated with E. coli (Fig. 4b), and the contribution of IL-12, IL-15, IFN-α on NK cytotoxicity of PBMC treated with S. aureus (Fig. 4c) as well as with HHV-6 (Fig. 4d). It is however, noteworthy that, among the cytokine-neutralizing antibodies used, treatment with anti-IL-15 antibody resulted in the highest decrease in NK killing activity for all three pathogens; on the other hand, an isotype-matched control antibody had no effect on the NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity (data not shown). This clearly demonstrates that IL-15 plays a major role in the up-regulation of NK activity following exposure to different pathogens. Moreover, we found that the combination of IL-15-neutralizing antibodies with other cytokine-neutralizing antibodies did not result in additive effect on the reduction of NK activity (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effect of different anti-cytokine antibodies on enhancement of NK activity by different pathogens. PBMC were treated with C. albicans (a), E. coli (b), S. aureus (c) and HHV-6 (d). followed by the addition of mAb against IL-15 (10µ/ml), IL-12 (10 µg/ml), IL-2 (10 µg/ml), IFN-α and TNF-α (10 µg/ml) separately. After 24 hr incubation at 37°, PBMC were harvested and their NK activity was determined by chromium release assay. Data are expressed as percentage of cytotoxicity, representing mean ± SEM. The experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. *, P < 0·05; **, P < 0·01; ***, P < 0·001 compared with PBMC stimulated with respective pathogen in the absence of mAb.

The NK activity of PBMC infected with HHV-6 in the presence of neutralizing antibodies to cytokine IL-15, IL-12, IL-2, IFN-α and TNF-α were also measured. The results obtained from this assay show that only anti-IL-15 mAb show a significant reduction of NK activity; we did not observe any significant reduction of NK cytotoxic killing activity using antibodies against the other cytokines (data not shown). These results confirmed our previous finding with HHV-629 as well as with different other viruses.28

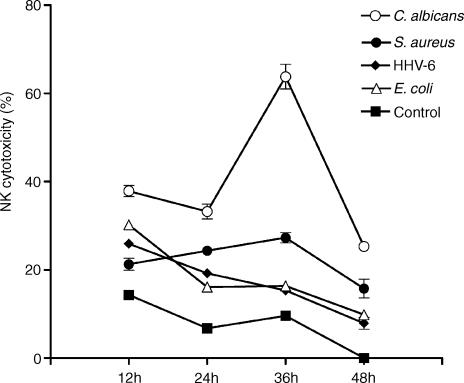

Kinetics analysis of NK activity following exposure to different pathogens

Because PBMC exposed to C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus and HHV-6 all displayed enhanced NK cytotoxicity, the next step of our study was to compare the kinetics of this NK activation by these different pathogens. Pathogen-treated and -untreated PBMC were collected at different time points (12, 24, 36 and 48 hr) PT, and their NK activities were measured as described in Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 5, two patterns of the NK kinetics were observed: one with a maximum NK activity very early following treatment (i.e. for E. coli and HHV-6); whereas in the other, the maximum NK activity occurred later (i.e. for C. albicans and S. aureus). HHV-6 and E. coli induced the highest NK cytolytic activity at 12 hr PT. After that rapid increase, the intensity of NK killing decreased gradually with time. A decrease of 3·3- and 3·1-fold were observed from 12 hr to 48 hr PT with HHV-6 and E. coli, respectively, whereas for C. albicans and S. aureus, the NK activity peaked later. The latter two agents induced a gradual increase of NK cytotoxicity (peaked at 36 hr PT) followed by a rapid loss of this activity at 48 hr PT. Although, both these pathogens showed the same kinetics of NK enhancement, S. aureus seemed to induce a smaller increase compared to C. albicans. An augmentation of 1·3-fold was observed from 12 hr to 36 hr PT for S. aureus compared to 1·7-fold for C. albicans. These data suggested that depending on the type of pathogen involved in the stimulation of human PBMC, the kinetics of NK cytotoxic activity can vary.

Figure 5.

Kinetic analyses of NK activity of PBMC exposed to different pathogens. PBMC treated with C. albicans, E. coli, S. aureus, and HHV-6 were collected at different time points (shown are the results for samples taken at 12, 24, 36 and 48 hr), and then resuspended at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/µl with complete medium. The NK cytotoxic activity was determined by measuring the chromium release by K562 labelled cells incubated with stimulated PBMC for 16 hr at 37°. The experiment was repeated three times and similar results were obtained. For all samples taken at 6 hr (not shown), the cytotoxic activity was below that observed for 12-hr samples.

Discussion

The innate immune system plays a key role in immune surveillance against pathogens, particularly during the early phase of infection. NK cells are a part of that innate defence as they can kill target cells without prior sensitization. This killing activity of NK cells has been shown previously to be up-regulated by several cytokines: e.g. IL-2, IL-12, IFN-α/γ, TNF.14,16 A relatively novel cytokine named IL-15, discovered by Grabstein et al.21 and Burton et al.36 has been shown to display the same ability as that of the cytokines mentioned above. Several studies have reported that IL-15 is critical in the defence against viral infections via activation of NK cells.28–31 Furthermore, recent evidence has emphasized the protective effects of IL-15 during bacterial and fungal infections.34,37–42 Therefore, in order to gain further knowledge about the role of IL-15 in the host's defence against fungal and bacterial infections, we sought to determine whether exposure of human PBMC to C. albicans, E. coli and S. aureus results in an immediate increase of NK cytotoxicity via IL-15 induction. The results presented here clearly demonstrate that C. albicans, E. coli and S. aureus up-regulate IL-15 gene expression which results in significant enhancement of NK cell activity of the PBMC. The addition of anti-IL-15 mAb to PBMC treated with these pathogens significantly down-regulates this NK activity. Furthermore, RT–PCR and Western blot analyses demonstrate the presence of IL-15 mRNA and protein, respectively. Therefore, these data clearly indicate that host's PBMC mount a strong IL-15 response to C. albicans, E. coli and S. aureus which results in a remarkable enhancement of their cytocidal (NK) activity.

Western blot analysis from PBMC treated with different pathogens revealed the presence of two bands migrating in close proximity on the gel (Fig. 2). Because IL-15 protein exists in two isoforms, i.e. short signal peptide (SSP) IL-15 and long signal peptide (LSP) IL-1536,43 our results suggest that the upper band (i.e. with higher molecular weight) is the LSP-IL-15 and the lower band is the SSP-IL-15. The upper band was darker suggesting that LSP-IL-15 was more abundantly produced than SSP-IL-15 by the pathogen-stimulated PBMC. Kurys et al. revealed that unprocessed and partially processed LSP-IL-15 forms were retained in the cells, whereas LSP-IL-15 with complete processing and N-glycosylation was secreted from the cell via Golgi apparatus.44 Because the first two forms of LSP-IL-15 are not secreted but remain in the producer cell, this may explain the high intensity of the upper band in the gel. The fact that the intensity of the lower band was faint suggests that SSP-IL-15 was weakly expressed; this result would confirm the observations by Kurys et al.44

The difference between the levels of IL-15 mRNA and protein expression observed in our study (Figs 2 and 3) would indicate that the regulation of IL-15 expression is mainly at the level of translation and post-translation. Previous studies reported that the upstream AUG codons of 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and the 48 amino acid signal peptide coding sequence of IL-15 mRNA, and the C-terminus of IL-15 protein-coding sequence negatively regulate the translation of IL-15 mRNA.45,46 Moreover, a recent study reported that intracellular trafficking of IL-15 protein also controls the expression of IL-1544 SSP-IL-15 protein, and unprocessed and partially processed LSP-IL-15 protein remain inside the producer cell; only LSP-IL-15 protein with complete processing of signal peptide and which is N-glycosylated can be secreted from the cell. This multifaceted regulation of IL-15 expression explains the difference between the level of IL-15 mRNA expression and the secreted protein. Because IL-15 protein expression observed in pathogen-treated PBMC in our study was higher than that of the untreated control cultures, this suggests that the pathogens may induce signal(s) that unlock negative regulatory control, allowing a more efficient translation and trafficking of IL-15 protein. Furthermore, the variation at the level of IL-15 protein expression observed with different pathogens suggests that, depending on the infectious agent involved, the induced signal may modulate and vary as to unlock one or several negative regulatory controls. This may explain the difference of IL-15 protein expression observed in our study with different pathogens.

The kinetic studies performed on NK activity of pathogen-stimulated PBMC showed two types of responses (Fig. 5). One with an early NK response that peaks at 12 hr PT and the other with an NK response that peaks at 36 hr PT. Our results show that IL-2, IL-12, IL-15, IFN-α and TNF-α also appear to be involved in this increase of NK activity by the pathogens (see Fig. 4). Moreover, as different types of pathogens were used to stimulate PBMC, we suggest that the contribution of each one of those cytokines in enhancing the NK activity may vary depending on the time of the stimulation and the type of pathogen involved. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 4, the contribution of IL-15, particularly in the early enhancement of NK activity (i.e. at 24 hr PT), is higher compared to other cytokines, in case of all the three pathogens tested.

In conclusion, human PBMC exposed to C. albicans, E. coli and S. aureus show an increase in NK activity caused mainly by IL-15 induction. The mechanisms, i.e. the receptors and signalling pathways involved in the up-regulation of IL-15 synthesis by these pathogens are presently unclear. Our preliminary data suggest that CD14 plays a role in such up-regulation by the non-viral pathogens (unpublished results). Further experiments are required to confirm this hypothesis. The production of IL-15 upon exposure of PBMC to fungi and bacteria is indeed an important proof of the implication of IL-15 in the host's innate immune response also against non-viral pathogens.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council of Canada (presently Canadian Institutes for Health Research) and the Immunobiology Program of the Ste-Justine Hospital Research Center. We thank Drs Louis de Repentigny and Céline Laferrière for culture seeds of Candida and bacteria, respectively, used for these studies.

References

- 1.Biron CA. Activation and function of natural killer cell responses during viral infections. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tay CH, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Welsh RM. Control of infections by NK cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;230:193–220. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46859-9_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arancia G, Stringaro A, Crateri P, Torosantucci A, Ramoni C, Urbani F, Ausiello CM, Cassone A. Interaction between human interleukin-2-activated natural killer cells and heat-killed germ tube forms of Candida albicans. Cell Immunol. 1998;186:28–38. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bancroft GJ. The role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:503–10. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90030-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griggs ND, Smith RA. Natural killer cell activity against uninfected and Salmonella typhimurium-infected murine fibroblast L929 cells. Nat Immun. 1994;13:42–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz P, Yeager H, Jr, Whalen G, Evans M, Swartz RP, Roecklein J. Natural killer cell-mediated lysis of Mycobacterium-avium complex-infected monocytes. J Clin Immunol. 1990;10:71–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00917500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appelberg R, Castro AG, Pedrosa J, Silva RA, Orme IM, Minopris P. Role of gamma interferon and tumor necrosis factor alpha during T-cell-independent and-dependent of Mycobacterium avium infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3962–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3962-3971.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tripp CS, Wolf SF, Unanue ER. Interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha are costimulators of interferon gamma production by natural killer cells in severe combined immunodeficiency mice with listeriosis, and interleukin 10 is a physiologic antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3725–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidore MR, Mislan TW, Murphy JW. Responses of murine natural killer cells to binding of the fungal target Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1489–99. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.4.1489-1499.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewitz SM, Dupont MP, Smail EH. Direct activity of human T lymphocytes and natural killer cells against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun. 1994;62:194–202. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.194-202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrante A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha potentiates neutrophil antimicrobial activity: increased fungicidal activity against Torulopsis glabrata and Candida albicans and associated increases in oxygen radical production and lysosomal enzyme release. Infect Immun. 1994;57:2115–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.7.2115-2122.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marodi L, Scheiber S, Anderson DC, MacDermott RP, Kochak HM, Johnston RB., Jr Enhancement of macrophage candidacidal activity by interferon-gamma. Increased phagocytosis, killing, and calcium signal mediated by a decreased number of mannose receptors. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2596–601. doi: 10.1172/JCI116498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy JW, Wu-Hsieh BA, Singer-Vermes LM, et al. Cytokines in the host response to mycotic agents. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32:203–10. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orange JS, Biron CA. Characterization of early IL-12, IFN-αβ, and TNF effects on antiviral state and NK cell responses during murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:4746–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvucci O, Mami-Chouaib F, Moreau JL, Chehimi J, Chouaib S. Differential regulation of interleukin-12 and interleukin-15 induced natural killer cell activation by interleukin-4. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2736–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carson WE, Giri JG, Lindemann MJ, et al. Interleukin-15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1395–403. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. The multifaceted regulation of interleukin-15 expression and the role of this cytokine in NK cell differentiation and host response to intracellular pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:19–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker TC, Wherry EJ, Boone D, Murali-Krishna K, Antia R, Ahmed R. Inerleukin 15 is required for proliferative renewal of virus specific memory CD8T cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1541–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azimi N, Nagai M, Jacobson S, Waldmann TA. IL-15 plays a major role in the persistence of Tax-specific CD8 cells in HAM/TSP patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14559–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251540598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yajima T, Nishimura H, Wajjwalku W, Harada M, Kuwano H, Yoshikai Y. Over expression of interleukin-15 in vivo enhances antitumor activity against MHC class-1 negative and -positive malignant through augmented NK activity and cytotoxic T-cell response. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:573–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabstein KH, Eisenmann J, Shanebeck K, et al. Cloning of a T cell growth factor that interacts with the β chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Science. 1994;264:965–8. doi: 10.1126/science.8178155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonuleit H, Wiedemann K, Muller G, Degwert J, Hoppe U, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of IL-15 mRNA and protein in human blood-derived dendritic cells: a role for IL-15 in attraction of T cells. J Immunol. 1997;158:2610–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson WE, Ross ME, Baiocchi RA, Marien MJ, Boiani N, Grabstein K, Caligiuri MA. Endogenous production of interleukin 15 by activated human monocytes is critical for optimal production of interferon-γ by natural killer cells in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2578–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI118321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giri JG, Kumaki S, Ahdieh M, et al. Identification and cloning of a novel IL-15 binding protein that is structurally related to the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:3654–63. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carson WE, Fehniger TA, Haldar S, et al. Potential role for interleukin-15 in the regulation of human natural killer cell survival. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:937–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI119258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leclerc G, Debacker V, De Smedt M, Plum J. Differential effects of interleukin-15 and interleukin-2 on differentiation of bipotential T/natural killer progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:325–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mrozek E, Anderson P, Caligiuri MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2632–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fawaz LM, Sharif-Askari E, Menezes J. Up-regulation of NK cytotoxic activity via IL-15 induction by different viruses: a comparative study. J Immunol. 1999;163:4473–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flamand L, Stefanescu I, Menezes J. Human herpesvirus-6 enhances natural killer cells cytotoxicity via IL-15. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1373–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI118557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad A, Sharif-Askari E, Fawaz L, Menezes J. Innate immune response of the human host to exposure with herpes simplex virus type-1: in vitro control of the virus infection by enhanced natural killer activity via interleukin-15 induction. J Virol. 2000;74:7196–203. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7196-7203.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gosselin J, Tomoïu A, Gallo RC, Flamand L. Interleukin-15 as an activator of natural killer cell-mediated antiviral response. Blood. 1999;94:4210–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanbe T, Utsunomiya K, Ishiguro A. A crossreactivity at the immunoglobulin E level of the cell wall mannoproteins of C. albicans with other pathogenic Candida and airborne yeast. Clin Exp Allergy. 1997;27:1449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cappuccino JG, Sherman N. Serial dilution agar plating procedure to quantitate viable cells. In: Cappuccino JG, Sherman N, editors. Microbiology: a Laboratory Manual. 3. Bedwood City: The Benjamin Cummings Publishing Co., Inc; 1992. pp. 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jullien D, Sieling PA, Uyemura K, Mar ND, Thomas HR, Modlin RL. IL-15, an immunomodulator of T cell responses in intracellular infection. J Immunol. 1997;158:800–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jingwu X, Ahmad A, D'Addario M, Knafo L, Jones JF, Prassad V, Dolcetti R, Menezes J. Analysis and significance of anti-LMP-1 antibodies in the sera of patients with EBV-associated diseases. J Immunol. 2000;164:2815–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burton JD, Bamford RN, Peters C, et al. A lymphokine, provisionally designated interleukin T and produced by a human adult T cell leukemia line, stimulates T-cell proliferation and the induction of lymphokine-activated killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4935–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirose K, Nishimura H, Matsuguchi T, Yoshikai Y. Endogenous IL-15 might be responsible for early protection by natural killer cells against infection with an avirulent strain of Salmonella choleraesuis in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:382–90. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musso T, Calosso L, Zucca M, et al. Interleukin-15 activates proinflammatory and antimicrobial functions in polymorphonuclear cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2640–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2640-2647.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimura H, Hiromatsu K, Kobayashi N, Grabstein KH, Paxton R, Sugamura K, Bluestone JA, Yoshikai Y. IL-15 is a novel growth factor for murine γδ T cells induced by Salmonella infection. J Immunol. 1996;156:663–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takano M, Nishimura H, Kimura Y, Mokuno Y, Washizu J, Itohara S, Nimura Y, Yoshikai Y. Protective roles of γδT cells and Interleukin-15 in Escherichia coli infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3270–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3270-3278.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vazquez N, Walsh TJ, Friedman D, Chanock SJ, Lyman CA. Interleukin-15 augments superoxide production and microbicidal activity of human monocytes against Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1998;66:145–50. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.145-150.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tagaya Y, Kurys G, Thies TA, Losi JM, Azimi N, Hanover JA, Bamford RN, Waldmann TA. Generation of secretable and non-secretable interleukin 15 isoforms through alternate usage of signal peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14444–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Onu A, Pohl T, Krause H, Bulfone-Paus S. Regulation of IL-15 secretion via the leader peptide of two IL-15 isoforms. J Immunol. 1997;158:255–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurys G, Tagaya Y, Bamford R, Hanover JA, Waldmann TA. The long signal peptide isoform and its alternative processing direct the intracellular trafficking of IL-15. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30653–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bamford RN, Battiata AP, Burton JD, Sharma H, Waldmann TA. Interleukin (IL) 15/IL-T production by the adult T cell leukemia cell line HuT-102 is associated with a human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 region/IL-15 fusion message that lacks many upstream AUGs that normally attenuates IL-15 mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:2897–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bamford RN, DeFilippis AP, Azimi N, Kurys G, Waldmann TA. The 5′ UTR, signal peptide and 3′ coding sequences of IL-15 participate in its multifaceted translational control. J Immunol. 1998;160:4418–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]