Abstract

Here we compare the degree of pancreatitis caused by cerulein in mice lacking 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) and in the corresponding wild-type mice. Intraperitoneal injection of cerulein in mice resulted in severe, acute pancreatitis characterized by oedema, neutrophil infiltration and necrosis and elevated serum levels of amylase and lipase. Infiltration of pancreatic and lung tissue with neutrophils (measured as increase in myeloperoxidase activity) was associated with enhanced lipid peroxidation (increased tissue levels of malondialdehyde). Immunohistochemical examination demonstrated a marked increase in immunoreactivity for intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), P-selectin and E-selectin in the pancreas and lung of cerulein-treated mice. In contrast, the degree of (1) pancreatic inflammation and tissue injury (histological score), (2) up-regulation/expression of P-selectin, E-selectin and ICAM-1, and (3) neutrophil infiltration was markedly reduced in pancreatic and lung tissue obtained from cerulein-treated 5-LO-deficient mice. These findings support the view that 5-LO plays an important, pro-inflammatory role in the acute pancreatitis caused by cerulein in mice.

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a common disease with great variability in severity. Whereas it runs a fairly benign course in most patients, in others, it can take a severe form, characterized by pancreatic glandular necrosis and significant mortality.1

The mortality rate for severe pancreatitis is about 29·8% whereas that for moderate pancreatitis is about 2·3%. The main causes of death include circulatory shock, cardiac insufficiency, renal, respiratory and hepatic failure. Therefore, it has been demonstrated that many patients with pancreatitis develop dysfunction of at least two organs, indicating that multiple organ failure (MOF) occurred.2 Acute pancreatitis is caused by various factors, but once proteolytic enzymes become activated and pancreatic tissues digested, patients show a similar pattern of aggravation and MOF follows. Thus, the prognosis of severe acute pancreatitis is highly dependent on prevention and on appropriate measures to prevent MOF.

Activated polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) are known to play an important role in tissue and organ damage.3,4 Elastase released from PMN, which degrades the extracellular matrix components such as elastin,5 fibronectin, proteoglycans6 and collagen,7 is considered to be one of the most important mediators of inflammatory tissue damage. The most frequently occurring complication in severe acute pancreatitis is pulmonary dysfunction, such as adult respiratory distress syndrome, which has been attributed to the action of activated PMN.8 It is now known that PMN migration and activation, occurring at the time of invasion, are controlled locally by cytokines.9 Thus, recently it has been suggested that both the systemic inflammatory response syndrome as well as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), associated with severe, acute pancreatitis, may be secondary to the excessive activation of leukocytes,11,10 which in turn, would result in the release of secondary pro-inflammatory cytokines including tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8,12–14 all of which play an important role in the pathogenesis of septic shock.15–18

Therefore, acute pancreatitis is also associated with pancreatic microvascular leakage that is a primary feature of inflammation and leads to plasma exudation into pancreatic interstitium.19 The formation of pancreatic oedema is the result of increased microvascular leakage in the pancreatic circulation. The exudation of plasma proteins into the pancreatic interstitium results in the activation of several biochemical pathways, followed by pancreatic damage. It therefore seems to be important to reduce microvascular leakage with plasma exudation into pancreatic tissue for the treatment of acute pancreatitis.

Peptidyl-leukotrienes are 5-lipoxygenase products of arachidonic acid metabolism20 and can increase vascular permeability and cause smooth-muscle contraction.21–23 These properties have led to the hypothesis that peptide leukotrienes are important mediators of acute pancreatitis. Recently, it has been demonstrated that a potent peptide leukotriene receptor antagonist, pranlukast hydrate (4-oxo-8-[4-(4phenylbutoxy)benzoylamino]-2-(tetrazol-5-yl)-4H-benzopyran hemihydrate) inhibits peptide leukotriene-induced bronchoconstriction and leukotriene D4 (LTDa)-induced increase in cutaneous vascular permeability24 as well as preventing the development of acute pancreatitis.

In this study, we have investigated the role of 5-LO in a model of cerulein-induced pancreatitis using 5-LO-deficient mice and 5-LO wild-type mice. In order to characterize the role of 5-LO in this model of pancreatitis, we have determined the following endpoints of the inflammatory response in 5-LO-deficient mice and in the corresponding wild-type mice: (1) serum amylase and lipase levels, (2) neutrophils infiltration, (3) adhesion molecules expression and (4) organ injury.

Materials and methods

Animals

Mice (4–5 weeks old, 20–22 g) with a targeted disruption of the 5-lipoxygenase gene (5-LOKO) and littermate wild-type controls (5-LOWT) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Harlan Nossan, Italy). Mice were housed in a controlled environment and provided with standard rodent chow and water. Animal care was in compliance with Italian regulations (D.M. 116192) on protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purpose, as well as with the EEC regulations (O.J. of E.C. L 358/1 18/12/1986).

Induction of pancreatitis

Animals were randomly divided into four groups (n = 40 for each group). The first group (5-LO-deficient) was treated with saline solution (0·9% NaCl) intraperitoneally (i.p.) and served as sham group. The second group (5-LO-deficient) was treated hourly (×5) with cerulein (50 µg/kg, suspended in saline solution, i.p.). In the third and forth groups, 5-LO wild-type mice received saline or cerulein administration, respectively. Mice were killed by exsanguination at 6 and 12 hr after the induction of pancreatitis. Blood samples were obtained by direct intracardiac puncture. Pancreas and lungs were removed immediately, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80° until assayed. Portions of these organ were also fixed in formaldehyde for histological and immunohistochemical examination.

Morphological examination

Paraffin-embedded pancreas and lung samples were sectioned (5 µm), stained with haematoxylin/eosin. Pancreas sections examined by an experienced morphologist, who was not aware of the sample identity. Acinar-cell injury/necrosis was quantified by morphometry as previously described.25 For these studies, 10 randomly chosen microscopic fields (×125) were examined for each tissue sample and the extent of acinar-cell injury/necrosis was expressed as the percent of the total acinar tissue. The criteria for injury/necrosis were the following: (1) the presence of acinar-cell ghosts; or (2) vacuolization and swelling of acinar cells and the destruction of the histoarchitecture of whole or parts of the acini, both of which had to be associated with an inflammatory reaction.

Determination of pancreatic oedema

The extent of pancreatic oedema was assayed by measuring tissue water content. For these latter measurements, freshly obtained blotted sample of pancreas was weighted on aluminium foil, dried for 12 hr at 95°, and reweighed. The difference between wet and dry tissue weight was calculated and expressed as a percent of tissue wet weight.

Immunohistochemical localization of E-selectin, P-selectin, and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)

At 6 hr after cerulein administration, the pancreas and lung were fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde and 8 µm sections were prepared from paraffin embedded tissues. After deparaffinization, endogenous peroxidase was quenched with 0·3% H2O2 in 60% methanol for 30 min The sections were permeabilized with 0·1% Triton-X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min Non-specific adsorption was minimized by incubating the section in 2% normal goat serum in phosphate buffered saline for 20 min Endogenous biotin or avidin binding sites were blocked by sequential incubation for 15 min with avidin and biotin. The sections were then incubated overnight with primary anti-E-selectin antibody (1 : 1000), anti-P-selectin antibody (1 : 500) anti-ICAM-1 antibody (1 : 500) or with control solutions. Controls included buffer alone or non-specific purified rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG). Immunocytochemistry photographs (n = 5) were assessed by densitometry. The assay was carried out by using Optilab Graftek software on a Macintosh personal computer (CPU G3-266).

Biochemical assays

Serum amylase and lipase levels were measured at 6 hr after cerulein injection by a clinical laboratory. Liver injury was assessed by measuring the rise in plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT, a specific marker for hepatic parenchymal injury), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, a non-specific marker for hepatic injury) and bilirubin. Results are expressed in international units per litre.

Myeloperoxidase activity

Myeloperoxidase activity, an index of PMN accumulation, was determined as previously described.26 Lung and pancreas tissues, collected at the specified time point, were homogenized in a solution containing 0·5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide dissolved in 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7) and centrifuged for 30 min at 20 000 g at 4°. An aliquot of the supernatant was then allowed to react with a solution of tetramethylbenzidine (1·6 mm) and 0·1 mm H2O2. The rate of change in absorbance was measured by a spectrophotometer at 650 nm. Myeloperoxidase activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme degrading 1 µmol of peroxide min−1 at 37° and was expressed in units per gram weight of wet tissue.

Lipid peroxidation measurement

The levels of malondialdehyde in the pancreatic and lung tissue samples were determined as an indicator of lipid peroxidation.27 Pancreas and lung collected at the specified time, were homogenized in 1·15% KCl solution. An aliquot (100 µl) of the homogenate was added to a reaction mixture containing 200 µl of 8·1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 1500 µl of 20% acetic acid (pH 3·5), 1500 µl of 0·8% thiobarbituric acid and 700 µl distilled water. Samples were then boiled for 1 hr at 95° and centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min The absorbance of the supernatant was measured by spectrophotometry at 650 nm.

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all compounds were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Company (Milan, Italy). Primary monoclonal P-selectin (CD62P) or ICAM-1 (CD54) for immunohistochemistry were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Reagents and secondary and non-specific IgG antibody for immunohistochemical analysis were from Vector Laboratories InC. Primary monoclonal anti-E-selectin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (DBA, Milan, Italy). All other chemicals were of the highest commercial grade available. All stock solutions were prepared in non-pyrogenic saline (0·9% NaCl; Baxter Healthcare Ltd, Thetford, UK).

Data analysis

All values in the figures and text are expressed as mean ± SEM of the mean of n observations. In the in vivo studies n represents the number of animals studied. In the experiments involving histology or immunohistochemistry, the figures shown are representative of at least three experiments performed on different experimental days. The results were analysed by one-way anova followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons. A P-value of less than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

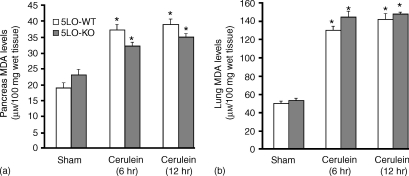

Lipid peroxidation in acute pancreatitis

At 6 and 12 hr after cerulein-induced pancreatitis, pancreas and lung were investigated for MDA levels, indicative of lipid peroxidation. As shown in Fig. 1, MDA levels were significantly increased in the pancreas as well as in the lung of cerulein-treated 5-LOWT mice (P < 0·01). The absence of 5-LO in mice did not modify the increase of MDA levels (Fig. 1a, b).

Figure 1.

Malondialdehyde levels in the pancreas (a) and in the lung (b) of cerulein-treated mice. At 6 and 12 hr following cerulein injection malondialdehyde levels were significantly increased in the pancreas as well as in the lung of the cerulein-treated 5-LO wild-type mice in comparison to sham mice. Absence of functional 5-LO in 5LO-KO mice did not interfere with the cerulein-induced increase in MDA levels. *P < 0·01 versus vehicle.

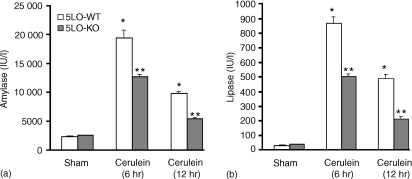

Acute pancreatitis is reduced in 5-LO-deficient mice

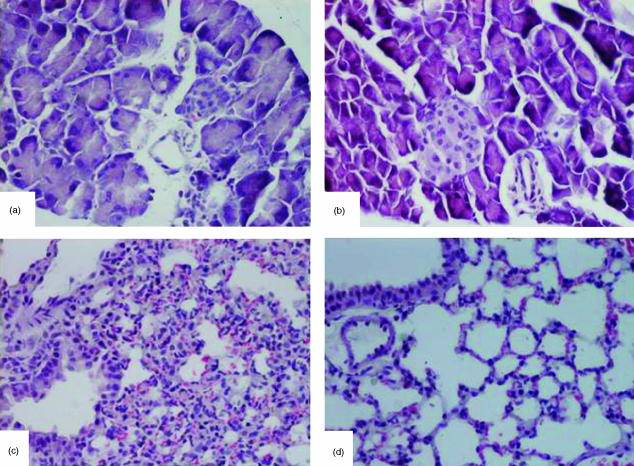

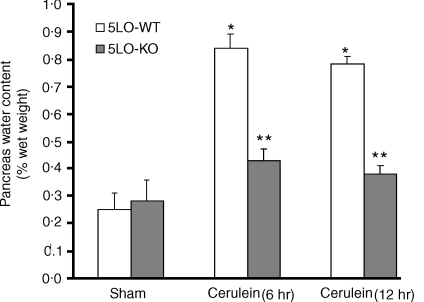

Cerulein-induced pancreatitis in 5-LO wild-type mice was associated with significant rises in the serum levels of lipase and amylase (Fig. 2). The increase in lipase and amylase was markedly reduced in 5-LO-deficient mice after cerulein administration (Fig. 2). In sham-saline wild type (data not shown) and 5-LO deficient mice (data not shown), the histological features of the pancreas were typical of a normal architecture. As described27,28 wild-type mice treated with i.p. injections of the secretagogue cerulein develop acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Histological examination (at 6 hr after the injection of cerulein) of pancreas sections from 5-LO wild-type mice revealed tissue damage characterized by inflammatory cell infiltrates and acinar cell necrosis (Fig. 3a; Table 1). Absence of a functional 5-LO gene in 5-LO-deficient mice resulted in a significant reduction of pancreatic injury (Fig. 3b; Table 1). Therefore, a significant pancreas oedema was observed at 6 and 12 hr after cerulein administration in comparison with sham-treated mice (Fig. 4). In contrast, no significant pancreas oedema was found at 6 and 12 hr after cerulean injection in the tissue from 5-LO deficient mice (Fig. 4).

Figure 2.

Amylase (a) and lipase (b) serum levels (U/l) in 5-LO wild-type and 5-LO-deficient mice. Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0·01 versus vehicle. **P < 0·01 represents significant reduction of the various parameters in the group in which 5-LO was absent.

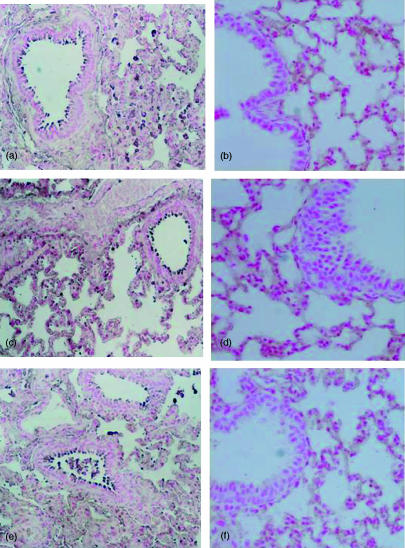

Figure 3.

Morphologic changes of pancreas and lung at 6 h after cerulein administration. Pancreas section from a cerulein-treated 5-LOWT mice showed interstitial oedema and infiltration of the tissue with inflammatory cells (a). Pancreas from cerulein-treated 5-LOKO mice shows reduced inflammatory cell infiltration and interstitial oedema (b). Representative lung sections from cerulein-treated 5-LOWT mice demonstrate inflammatory cells infiltration (c). Lung sections from cerulein-treated 5-LOKO mice (d) demonstrate reduced inflammatory cells infiltration. Original magnification: 125×. Figure is representative of at least three experiments performed on different experimental days.

Table 1.

Histological scoring of acute pancreatitis lesions.

| Oedema | Inflammation | Necrosis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-LOSWT + CER | 1·8 ± 0·2 | 2·1 ± 0·12 | 2·58 ± 0·1 |

| 5-LOKO + CER | 0·64 ± 0·11* | 0·42 ± 0·09* | 0·76 ± 0·12* |

The above parameters were evaluated at 6 hr following cerulein (CER) injection.

P < 0·01 represents significant reduction of the various parameters in the group in which 5-LO was absent.

Figure 4.

Effects of absence of a functional 5-LO gene in 5-LO deficient mice on water content (index of oedema) in the pancreas at 6 and 12 hr after cerulean-induced acute pancreatitis. Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0·01 versus vehicle. °P < 0·01 represents significant reduction of the various parameters in the group in which 5-LO was absent.

Acute lung injury is reduced in 5-LO-deficient mice

Histological examination (at 6 hr after the injection of cerulein) of lung sections from cerulein-treated 5-LOWT-type mice revealed tissue damage characterized by presence of interstitial oedema, infiltration of the tissue with inflammatory cells and vein wall damage (Fig. 3c). Absence of a functional 5-LO gene in 5-LO-deficient mice resulted in a significant reduction of pulmonary injury (Fig. 3d). In saline-treated controls the histological features of the lung were typical of normal architecture (data not shown).

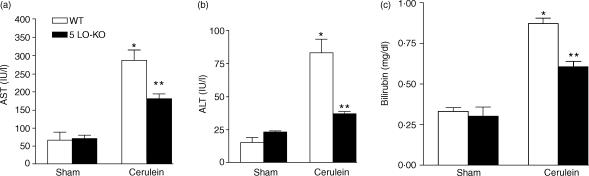

Liver injury is reduced in 5-LO-deficient mice

In sham-operated 5-LO-deficient mice or 5-LOWT mice no significant alterations in the plasma levels of AST, bilirubin and ALT were observed (Fig. 5). When compared with sham-operated mice, cerulein administration in 5-LOWT mice resulted in significant rises in the plasma levels of bilirubin, AST and ALT, demonstrating the development of hepatocellular injury. Absence of a functional 5-LO gene in 5-LO-deficient mice reduced the liver injury caused by cerulein administration (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Plasma levels of (a) AST (b) ALT and bilirubin (c) in mice subjected to cerulein- induced acute pancreatitis. *P < 0·01 versus vehicle. °P < 0·01 represents significant reduction of the various parameters in the group in which 5-LO was absent.

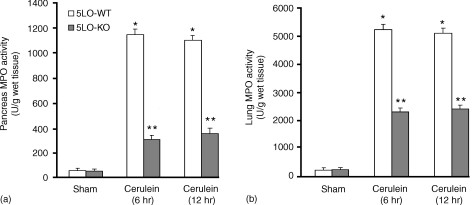

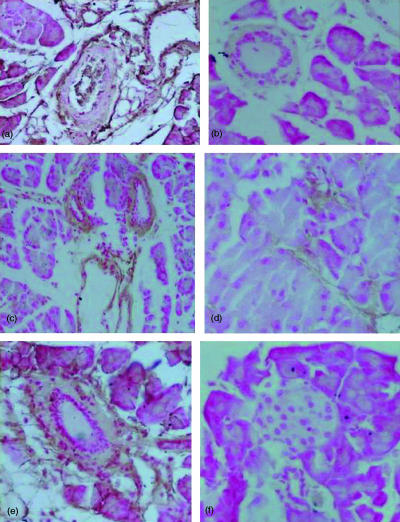

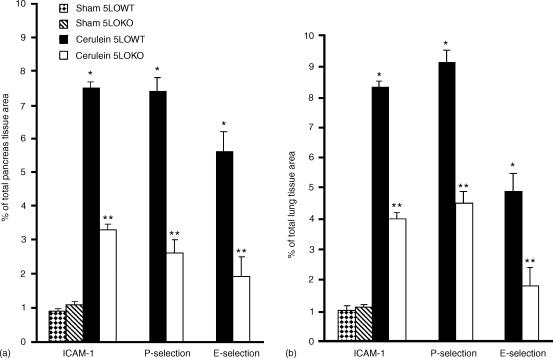

E-selectin, P-selectin and ICAM-1 expression and neutrophil infiltration is reduced in 5-LO-deficient mice

A hallmark of acute pancreatitis is the accumulation of neutrophil in the pancreas and in the lung, which augments the tissue damage. Therefore, we have evaluated the extent of the expression of E-selectin, P-selectin and ICAM-1, adhesion molecules, which play a pivotal role in the rolling and firm attachment of neutrophils to the endothelium. Assessment of neutrophil infiltration into the pancreas and in the lung was also performed by measuring the activity of myeloperoxidase, an enzyme that is contained in (and specific for) PMN lysosomes. Thus, tissue levels of MPO directly correlate with the number of neutrophils in any given tissue. Myeloperoxidase activity was significantly increased after cerulein administration in pancreas (Fig. 6a) and in lung (Fig. 6b) from 5-LOWT mice. MPO activity was markedly reduced in pancreas (Fig. 6a) and lung (Fig. 6b) from 5-LOKO mice. The increase in MPO activity was associated and correlated with the increase of imunohistochemical staining for ICAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin in the vessels wall of the inflamed pancreas (Fig. 7a, c, e, respectively, Fig. 8a) as well as in pulmonary tissue (Fig. 9a, c, e, respectively, and Fig. 8b). The immunostainings for ICAM-1, E-selectin and P-selectin were markedly reduced in pancreas (Fig. 7b, DF, respectively, Fig. 8a) as well as in the lungs (Fig. 9b, d, f, respectively, and Fig. 8b) from cerulein-treated 5-LO-deficient mice. Note that there was no staining for either ICAM-1, E-selectin or P-selectin in pancreas obtained from sham-treated mice (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Myeloperoxidase activity levels in the pancreas (a) and in the lung (b) of cerulein-treated mice. At 6 and 12 hr following cerulein injection myeloperoxidase activity was significantly increased in the pancreas and in the lung of the cerulein-treated 5-LO wild-type mice in comparison to sham mice. Absence of functional 5-LO in 5LO-KO mice significantly reduce the cerulein-induced increase in MPO activity. *P < 0·01 versus vehicle. **P < 0·01 represents significant reduction of the various parameters in the group in which 5-LO was absent.

Figure 7.

Immunohistochemical localization of ICAM-1 E-Selectin and P-selectin in the pancreas at 6 hr after cerulein administration. Section obtained from cerulein-treated 5-LOWT mice showed intense positive staining for ICAM-1 (a), E-Selectin (c) and for P-selectin (e) around the vessels. The degree of pancreas staining for ICAM-1 (b), E-selectin (d) and for P-selectin (f) was markedly reduced in tissue section obtained from cerulein-treated 5-LO-deficient mice. Original magnification: ×145. Figure is representative of at least three experiments performed on different experimental days.

Figure 8.

Typical densitometry evaluation. Densitometry analysis of immunocytochemistry photographs (n = 5) for ICAM-1, P-selectin and E-selectin from pancreas (a) and from lung section (b) was assessed. The assay was carried out by using Optilab Graftek software on a Macintosh personal computer (CPU G3-266). Data are expressed as percentage of total tissue area. *P < 0·01 versus sham. °P < 0·01 versus 5-LOWT mice.

Figure 9.

Immunohistochemical localization of ICAM-1 E-selectin and P-selectin in the lung at 6 hr after cerulein administration. Section obtained from cerulein-treated 5-LO wild-type mice showed intense positive staining for ICAM-1 (a), E-selectin (c) and for P-selectin (e) around the vessels. The degree of lung staining for ICAM-1 (b), E-selectin (d) and for P-selectin (f) was markedly reduced in tissue section obtained from cerulein-treated 5-LO-deficient mice. Original magnification: ×145. Figure is representative of at least three experiments performed on different experimental days.

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis is a pathological condition with clinical presentations varying from mild forms, in which the condition resolves following a single episode of transient abdominal symptoms, to severe, life-threatening variants in which the onset of haemorrhagic/necrotic acute pancreatitis occurs early in the disease. The mortality rate for severe acute pancreatitis is extremely high at 30–50% and death is caused by dysfunction in organs other than the pancreas, such as the lungs, liver, kidneys and heart.29 The identification of clinical parameters that induce MOF in acute pancreatitis is the key factor in managing and preventing the complications associated with this condition.

We report here that mice with a targeted deletion of the 5-LO gene (5-LO-deficient mice or 5-LOKO mice) are protected against experimental pancreatitis. Here we demonstrate that the lack of 5-LO gene reduces (1) the development of cerulein-induced pancreatitis, (2) pancreas injury, (3) liver injury, (4) lung injury, (5) neutrophil infiltration, and (6) E-selectin, P-selectin and ICAM-I expression. All of these findings support the view that enhanced leukotriene generation from 5-LO plays an important role in the pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis. Thus, we propose that an enhanced formation of leukotriene by 5-LO contributes to the pathophysiology of pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis is a common and potentially fatal disease. During the last 10 years, the role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of acute pancreatitis has been recognized. Indeed, many different interventions, which either reduce the generation and/or the effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS), have been reported to exert beneficial effects in animal models of pancreatitis.30–34 For instance, there is evidence that free radicals,30,35 chemokines36 and pro-inflammatory cytokines37,38 play an important role in the pathophysiology of the acute pancreatitis caused by cerulein in rodents.

Some important tissue-damaging and pro-inflammatory roles attributed to ROS include: endothelial cell damage and increased microvascular permeability39–41 formation of chemotactic factors such as leukotriene B4,42,43 recruitment of neutrophils at sites of inflammation,44,45 lipid peroxidation and oxidation, and DNA single-strand damage.46 In the present study we have confirmed that acute pancreatitis is characterized by a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in the pancreas and in the lung. Therefore, the absence of 5-LO did not reduced the lipid peroxidation induced by cerulein administration. Leukotrienes, biologically active 5-LO metabolites of arachidonic acid, have been implicated in the pathological manifestations of inflammatory diseases, including asthma, arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease.47 The contribution of leukotrienes to a specific inflammatory response depends both on the ability of cells present in the inflammatory lesion to produce a particular leukotrienes and the response of the tissue to these bioactive lipids. 5-LO is expressed predominantly by cells of myeloid origin, particularly neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes/macrophages, and mast cells.48,49 Therefore, the contribution of the AA metabolites produced by the enzymes of the 5-LO pathway to inflammatory pathophysiology is supported by the identification of high levels of leukotriene in ischaemia and reperfusion and by the demonstration that introduction of leukotriene into normal tissue can elicit a number of the primary signs of ischaemia and reperfusion.

A significant increase of leukotriene formation in the pancreas was associated with experimental acute pancreatitis.50 Furthermore, the potent peptide leukotriene receptor antagonist, pranlukast hydrate (4-oxo-8-[4-(4-phenylbutoxy)benzoylamino]-2-(tetrazol-5-yl)-4H-benzopyran hemihydrate) significantly improved pancreas function and abrogated cellular inflammatory responses associated with experimental acute pancreatitis.51 These data suggest that arachidonate 5-LO synthesis plays a significant role in acute pancreatitis.

Therefore, recently it has been demonstrated that leukotriene generation seem to be more closely correlated to the later infiltration of PMN.52

Endothelial adhesion molecules are major regulators of neutrophil traffic, regulating the process of neutrophil chemoattraction, adhesion, and emigration from the vasculature to the tissue. P-selectin is rapidly released to the endothelial surface from preformed storage pools after exposure to certain stimuli such as hydrogen peroxide, thrombin, histamine or complement and allows the leukocytes to roll along the endothelium.52 E-selectin is expressed in skin microvessels under baseline conditions53 and there is some evidence that E-selectin is of particular importance in skin inflammation, because it supports the recruitment of skin-specific T lymphocytes.54 ICAM-1, constitutively expressed on the surface of endothelial cells, is then involved in the neutrophil adhesion.52,55 We observed that cerulein induced the appearance of P-selectin, E-selectin on the endothelium of small vessels, and up-regulated the surface expression of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells in pancreas and lung from 5-LOWT mice. In contrast, we demonstrated significant reduction in the expression of P-selectin, E-selectin and ICAM- 1 in pancreas and lung tissues from 5-LO-deficient mice compared to wild-type mice at 6 hr after cerulein administration. Interestingly, we found that the constitutive expression of ICAM-1 in the pancreas and lung did not differ between sham 5-LO-deficient and wild-type mice (data not shown). Taken together with the finding of a marked reduction of the inflammatory cell infiltration in 5-LO-deficient mice, these data suggest that 5-LO does not modulate the constitutive expression of adhesion molecules. The absence of 5-LO, however, appears to inhibit the expression of E-selectin, P-selectin and ICAM-1 in acute pancreatitis, regulating neutrophil recruitment both at the rolling and firm adhesion phase. In fact, there was a good correlation between the significant reduction of leukocyte infiltration in 5-LO-deficient mice (when compared to 5-LO wild-type mice) and the reduced tissue damage, as evaluated by histological examination.

The excessive PMN activation together with the impaired phagocytosis can be related to the onset of complications in severe acute pancreatitis.56,57 Recently Wilemer et al. have reported that the initial manifestation of pancreatitis-associated lung injury was a pronounced clustering of PMN in pulmonary microvessels, which was followed by severe damage to alveolar endothelial cells.58 The increase in vascular permeability of the lung then resulted in interstitial oedema formation. Thus, PMN play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis-related lung injury. In the present study we have clearly demonstrated that the absence of functional 5-LO gene significantly prevents the neutrophil infiltration in the lung as well as the lung damage. Therefore, severe acute pancreatitis is often complicated by intraperitoneal infection, resulting in MOF. Several studies have demonstrated that cytokines such us TNF-α may play a role in the development of MOF (e.g. liver injury) during acute pancreatitis.2,59 In the present study we have demonstrated that cerulein administration in 5-LOWT mice resulted in significant rises in the plasma levels of bilirubine, AST and ALT, demonstrating the development of hepatocellular injury. In contrast the absence of functional 5-LO in 5-LOKO mice reduced the liver injury caused by acute pancreatitis.

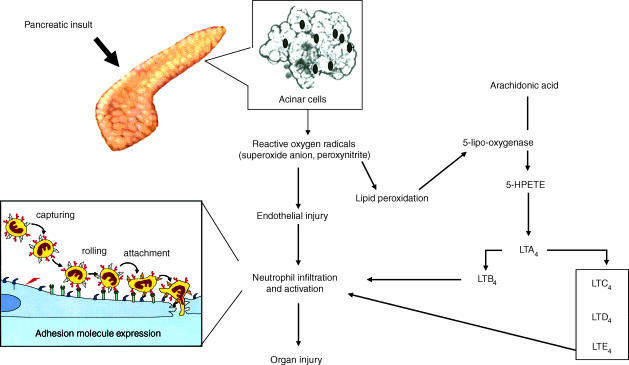

In conclusion, the discovery of the concept that 5-LO regulates neutrophil trafficking may provide new insights in the interpretation of recent reports demonstrating the protective effect of 5-LO inhibition in experimental models of acute pancreatitis. In conclusion, this study demonstrates for the first time that 5-LO inhibition attenuates: (1) the pancreatic dysfunction and injury; (2) the hepatocellular dysfunction; and (3) the lung injury caused by cerulein administration in the mice. Thus, we propose (Fig. 10) the following positive feedback cycle in acute pancreatitis: ROS production >> lipid peroxidation >> 5-LO activation >> adhesion molecule expression >> PMN infiltration >> tissue damage.

Figure 10.

Proposed scheme of some of the potential sites for the protective actions of inhibition of 5-LO. Removal of leukotrienes production affects the inflammatory cascade by inhibiting neutrophil infiltration at the site of inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant Ministero della Pubblica Istruzio. The authors would like to thank Giovanni Pergolizzi and Carmelo La Spada for their excellent technical assistance during this study, Mrs Caterina Cutrona for secretarial assistance and Miss Valentina Malvagni for editorial assistance with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bradley EL., II A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg; Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis; September 11 Through 13 1992; Atlanta GA. 1993. p. 586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogawa M. Acute pancreatitis and cytokines: ‘second attack’ by septic complication leads to organ failure. Pancreas. 1998;16:312–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malech HL, Gallin JI. Current concepts: immunology. Neutrophils in human diseases. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:687–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709103171107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss SJ. Tissue destruction by neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:365–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198902093200606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGowan SE, Murray JJ. Direct effects of neutrophil oxidants on elastase-induced extracellular matrix proteolysis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:1286–93. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.6.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald JA, Kelley DG. Degradation of fibronectin by human leukocyte elastase. Release of biologically active fragments. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:8848–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mainardi CL, Hasty DL, Seyer JM, Kang AH. Specific cleavage of human type III collagen by human polymorphonuclear leukocyte elastase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:12006–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lankish PG, Ralph G, Koop H. pulmonary complications in fatal hemorrhage acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:111–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01315139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsujimoto M, Yokota S, Vilcek J, Weissmann G. Tumor necrosis factor provokes superoxide anion generation from neutrophils. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;137:1094–100. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinderknecht H. Fatal panreatitis: a consequence of excessive leukocyte stimulation? Int J Pancreatol. 1988;3:105. doi: 10.1007/BF02798921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominguez-Munoz JE, Carballo F, Garcia MJ, et al. Monitoring of serum proteinase–antiproteinase balance and systemic inflammatory response in prognostic evaluation of acute pancreatitis: results of a prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;82:6. doi: 10.1007/BF01316507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusske AM, Rongione AJ, Reber HA. Cytokines and acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:639. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.agast960639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Formela LJ, Galloway SW, Kingsnorth AN. Inflammatory mediators in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1995;82:6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholmerich J. Interleukins in acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;219:37. doi: 10.3109/00365529609104998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beutler B, Milsark IW, Cerami AC. Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effects of endotoxin. Science. 1985;229:869. doi: 10.1126/science.3895437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tracey KJ, Fong Y, Hesse DG, et al. Anti cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature. 1987;330:662. doi: 10.1038/330662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wage A, Brandtzaeg P, Halstensen A, Kerful P, Espevik T. The complex pattern of cytokines in serum from patients with meningococcal septic shock: association between interleukin-6, interleukin-1, and fatal outcome. J Exp Med. 1989;169:333. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hack CE, Hart M, van Schijndel RJ, et al. Interleukin-8 in sepsis: relation to shock and inflammatory mediators. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2835. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2835-2842.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanfey H, Cameron JL. Increased capillary permeability: an early lesion in acute pancreatitis. Surgery. 1984;96:485–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moris HR, Taylor GW, Piper PJ, Tippins JR. structure of slow reacting substance of anaphylaxis from guinea pig lung. Nature. 1980;285:104–6. doi: 10.1038/285104a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LE Bemis KG, Fleisch JH. Production and antagonism of cutaneous vascular permeability in the guinea pig in response to histamine, leukotrienes and A23187. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;230:550–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dahlen SE, Hedqvist P, Hammarstrom S, Samuelsson B. Leukotrienes are potent constrictors of human bronchi. Nature. 1980;28:8484–6. doi: 10.1038/288484a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drazen JM, Austen KF, Lewis RA, Clark DA, Goto G, Marfat A, Corey EJ. Comparative airway and vascular activities of leukotrienes C-1 and D in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:4354–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakai H, Konno M, Kosuge S, et al. New potent antagonists of leukotrienes C4 and D4 1. Synthesis and structure–activity relationships. J Med Chem. 1988;31:84–91. doi: 10.1021/jm00396a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopken UE, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C. The C5a chemoattractant receptor mediates mucosal defence to infection. Nature. 1996;383:86. doi: 10.1038/383086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grady T, Saluja AK, Kaiser A, Steer ML. Edema and intrapancreatic trypsinogen activation precedes glutathione depletion during caerulein pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G20. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.271.1.G20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mullane KM, Kraemer R, Smith B. Myeloperoxidase activity as a quantitative assessment of neutrophil infiltration into ischemic myocardium. J Pharmacol Methods. 1985;141:57. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(85)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dignam JD, Lebowitz RM, Roeder RG. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nucleii. Nucl Acid Res. 1983;11:1475. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikei S, Ogawa M, Yamaguchi Y. Blood concentrations of polymorphonuclear leucocyte elastase and interleukin-6 are indicators for the occurrence of multiple organ failures at the early stage of acute pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1274–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luthen R, Grendell JH, Haussinger D, Niederau C. Beneficial effects of L-2-oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylate on cerulein pancreatitis in mice. Gastrenterology. 1997;112:1681. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Ferrel LD, Sukhabote RJ, Grendell JH. Glutathione monoethyl ester ameliorates caerulein-induced pancreatitis in the mouse. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:109. doi: 10.1172/JCI115550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wisner J, Green D, Ferrel L, Renner I. Evidence for a role of oxygen derived free radicals n the pathogenesis of caerulein induced acute pancreatitis in the rats. Gut. 1988;29:1516. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.11.1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wisner JR, Renner IG. Allopurinol attenuates caerulein induced acute pancreatitis in the rat. Gut. 1988;29:926. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.7.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederau Ferrel LD, Grendell JH. Caerulein-induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis in mice. protective effects of proglumide, benzocript and secretin. Gastroenterlogy. 1985;88:1192. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guice KS, Miller DE, Oldham KT, Townsend M, Thompson JC. Superoxide dismutase and catalase: a possible role in established pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1986;151:163. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(86)90027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fu K, Sarras MP, De Lisle R, Andrews GK. Expression of oxidative stress-responsive genes and cytokine genes during cerulein-induced cute pancreatitis. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G696. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.3.G696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grady T, Liang P, Ernst S, Logsdon D. Chemokine gene expression in rat pancreatic acinar cells is an early event associated with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterolgy. 1997;113:1966. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norman JG, Fink GW, Denham W, et al. Tissue-specific cytokine production during experimental acute pancreatitis: a probable mechanism for distant organ dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1783. doi: 10.1023/a:1018886120711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Droy-Lefaix MT, Drouet Y, Geraud G, Hosford D, Braquet P. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) and the PAF-antagonist (BN 52021) reduce small intestinal damage induced by ischemia–reperfusion. Free Radic Res Commun. 1991;2:725–35. doi: 10.3109/10715769109145852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haglind E, Xia G, Rylander R. Effects of antioxidants and PAF receptor antagonist in intestinal shock in the rat. Circ Shock. 1994;42:83–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Substrate control of free radical generation from xanthine oxidase in the postischemic heart. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18797–803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fantone JC, Ward PA. A review: role of oxygen-derived free radicals and metabolites in leukocyte-dependent inflammatory reactions. Am J Pathol. 1982;107:395–418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deitch EA, Bridges W, Berg R, Specian RD, Granger DN. Hemorrhagic shock-induced bacterial translocation: the role of neutrophils and hydroxyl radicals. J Trauma. 1990;30:942–52. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boughton-Smith NK, Deakin AM, Follenfant RL, Whittle BJ, Garland LG. Role of oxygen radicals and arachidonic acid metabolites in the reverse passive Arthus reaction and carrageenin paw oedema in the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:896–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salvemini D, Wang ZQ, Bourdon DM, Stern MK, Currie MG, Manning PT. Evidence of peroxynitrite involvement in the carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;303:217–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dix TA, Hess KM, Medina MA, Sullivan RW, Tilly SL, Webb TL. Mechanism of site-selective DNA nicking by the hydrodioxyl (perhydroxyl) radical. Biochemistry. 1996;35:4578–83. doi: 10.1021/bi952010w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson WR., Jr The role of leukotrienes in inflammation. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:684–97. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-9-199411010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Byrne PM. Eicosanoids and asthma. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;744:251–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb52743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fretland DJ, Djuric SW, Gaginella TS. Eicosanoids and inflammatory bowel disease. regulation and prospects for therapy. Prostaglandins Leukotr Essent Fatty Acids. 1990;41:215–33. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(90)90135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Folch E, Closa D, Prats N, Gelpi E, Rosello-Catafau J. Leukotriene generation and neutrophil infiltration after experimental acute pancreatitis. Inflammation. 1998;22:83–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1022399824880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirano T. Peptide leukotriene receptor antagonist diminishes pancreatic edema formation in rats with cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:84–8. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorant DE, Patel KD, McIntyre TM, McEver RP, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Coexpression of GMP-140 and PAF by endothelium stimulated by histamine or thrombin: a juxtacrine system for adhesion and activation of neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novelli GP. Oxygen-radicals in experimental shock: effects of spin-trapping nitrones in ameliorating shock pathophysiology. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:499. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199204000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Picker LJ, Kishimoto TK, Smith CW, Warnock RA, Butcher EC. ELAM-1 is an adhesion molecule for skin-homing T cells. Nature. 1991;349:796–9. doi: 10.1038/349796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wetheimer SJ, Myers CL, Wallace RW, Parks TP. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:12030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scholmerich J. Interleukins in acute pancreatitis. Review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1996;219:37–42. doi: 10.3109/00365529609104998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liras G, Carballo F. An impaired phagocytic function is associated with leucocyte activation in the early stages of severe acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1996;39:39–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willemer S, Feddersen CO, Karges W, Adler G. Lung injury in acute experimental pancreatitis in rats. I. Morphological studies. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;8:305–21. doi: 10.1007/BF02952723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sameshima H, Ikei S, Mori K, Yamaguchi Y, Egami H, Misumi M, Moriyasu M, Ogawa M. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the aggravation of cerulein-induced pancreatitis in rats. Int J Pancreatol. 1993;14:107–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02786116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]