Abstract

Antigenic cross-reactivity between certain tumours has allowed the development of more widely applicable, major histocompatibility complex-disparate (allogeneic) whole-cell vaccines. This principle should also allow heat shock proteins (hsp) derived from certain tumours (and carrying cross-reactive antigens) to be used as vaccines to generate anti-tumour immunity in a range of cancer patients. Here, hsp70 derived from gp70-antigen+ B16 melanoma generated cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-mediated immune protection in BALB/c mice against challenge with gp70-antigen+ CT26 colorectal tumour cells. Using ovalbumin as a model tumour antigen, it is shown that hsp70 enhances peptide re-presentation by dendritic cells via class I over equimolar whole ovalbumin antigen. However, while transfection of tumour cells with inducible hsp70 increases hsp yield from tumours, it does not enhance antigen recognition via purified hsp70 nor via whole cells or their lysate.

Introduction

The promise of utilizing the immune response in combating cancer has encouraged a great deal of laboratory and clinical research, but has come to relatively little fruition in terms of providing patient treatment options.1 This may be because tumour immunotherapy is generally a complicated, expensive, patient-specific and unproven treatment avenue. There is little doubt that the immune system can recognize and destroy cancer cells. Indeed, a large number of tumour-associated or tumour-specific antigens have been identified, often based on their recognition by the T cells of cancer patients.2 However, the ability of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to kill tumour cells, which is considered one of the most important events in tumour immunotherapy, is likely to be inefficient if the tumour burden is very high for logistical reasons (magnitude of immune response3) as well as because of immune suppression.4 Apart from reducing the tumour burden by surgery and other means a way of tipping the balance against tumours is to modify and increase the anti-tumour response by vaccination. An anti-tumour vaccine may take a number of forms including whole irradiated tumour cells, often with additional adjuvants such as bacillus Calmette–Guérin5 and transduced cytokines,6 tumour-derived antigens possibly pulsed onto autologous dendritic cells (DCs)7 and antigen–DNA vaccines.8 One form of subunit tumour vaccine comprises chaperone proteins [heat shock proteins (hsp)] extracted from autologous tumour.9 These hsp, the main players being hsp70, hsp90, gp96, gp110 and calreticulin, are able to bind to and transport tumour-derived antigens to host antigen-presenting cells (chiefly DC), thus promoting the priming of antigen-specific T cells.10–12 The hsp also have the ability to stimulate and activate antigen-presenting cells,13 enhancing their ability to prime T cells. Moreover, the cellular induction of hsp by various stresses in addition to heating has been shown to enhance both the immune recognition and immunogenicity of tumour cells.14–18

It has been maintained that hsp must be derived from the tumour against which vaccination is pursued, similar in principal to a need for autologous whole-cell vaccination,19 so that antigens are exactly matched. However, it is clear that the majority of tumours of a given histological origin will express a number of antigens in common which could serve as targets for an effective immune response.20 This principle has allowed the investigation and use of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-disparate (allogeneic) tumour cells as effective vaccines.21–24 Thus, in principle, hsp derived from non-autologous but related tumours should also be able to prime or activate effective T cells. This has recently been shown for hsp70 derived from human melanoma in vitro using CTL clones specific for known melanoma antigens.25,26

The aim of this study was to evaluate the use of an hsp70 vaccine, in BALB/c mice, derived from an allogeneic tumour cell line (B16), which expresses an antigen common to the syngeneic tumour challenge (CT26). A model antigen, ovalbumin, was used to investigate mechanisms by which hsp70 may facilitate antigen re-presentation.

Methods

Animals and cell lines

BALB/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Harlan UK (Bicester, UK) and used at between 6 and 12 weeks of age. All procedures were carried out in accordance with Government guidelines. CT26 (H-2d) murine colorectal tumour, B16-F10 (H-2b) and K1735 (H-2k) murine melanoma and RENCA (H-2d) renal carcinoma lines have been described in our previous studies.27–29 Ovalbumin-transfected B16 cells (B16-OVA cells) were provided by P. Dellabona,30 the DC2.4 DC line was provided by K. Rock31 and B3Z SIINFEKL-specific T-cell hybridoma was given by N. Shastri.32 Tumour cell lines were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mm glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Sigma, Poole, UK). The adherent lines were detached from the flasks with 0·05% trypsin/0·02% EDTA and for in vivo inoculation were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cell lines were all free of mycoplasma, as determined by the Gene-Probe method (Gene-Probe, San Diego, CA). Retroviral transfection with the inducible murine hsp7014 was carried out as described previously.33 Puromicin, resistance to which was encoded by the gene construct, was used in the medium at 1·25 μg/ml.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from tumour cell pellets by homogenization with TRIZOL solution (Sigma), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two micrograms of RNA, as estimated by the absorbance ratio for 260 : 280 nm, were reverse transcribed at 37° for 1 hr using the ‘first-strand cDNA synthesis kit’ (Novagen/Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. An equivalent of 100 ng of resulting cDNA were added to reaction mixtures containing 2 μl 10× buffer (10 mm Tris HCl, 50 mm KCl, 0·01% gelatine), 160 μm dNTPs (Amersham Pharmarcia-Biotech, St Albans, UK), 2·5 mm MgCl2, 0·25 U Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT) and 0·5 μm of each primer, the sequences for gp70 have been previously published.34 Amplification was performed on a PTC-100 DNA thermal cycler for 35–40 cycles. Products were visualized on 1·5% (wt/v) agarose gels with appropriately sized markers (Amersham Pharmacia-Biotech). All samples were initially subjected to PCR with primers for the housekeeping gene GAPDH to confirm successful RNA extraction and reverse transcription, and also to verify that the amounts of input cDNA were constant for each reaction. RNA was shown to be free of genomic DNA contamination by directly amplifying the equivalent amount of RNA as was used in the subsequent RT-PCR reactions (not shown).

Extraction of hsp70

The hsp70 was extracted from B16 tumour cells by a modified method.35 Tumour cells that had been growing as a solid mass in vivo were excised from killed mice. It was found that these tumours were of an unstructured nature and so did not require enzymatic digestion, but simply vigorous mixing by shaking in PBS to release the cells; 4 g of tissue was processed. Washed and pelleted cells were homogenized on ice in a glass dounce and then sonicated on ice in 10 mm HEPES buffer, pH 7. Following two rounds of freeze–thawing and centrifugation at 10 000 g, the soluble fraction was made up to 15 mm 2-ME, 3 mm MgCl2, 20 mm NaCl, and was passed over a Sepharose–ADP column (Sigma), washed thoroughly and then eluted with ADP without 2-ME. Excess ADP was removed at the same time as buffer exchange to PBS, and concentration, using a centricon filter system. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay and by reference to the gel used for sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE). For Western blotting the samples were transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with an anti-hsp70 monoclonal antibody (BRM-22, Sigma). The same procedure was used to extract hsp70 from K1735 cells.

In vivo experiments

Groups of four to eight female, age-matched mice were injected subcutaneously in the shaven flank either with lethal tumorigenic doses of tumour cells, with irradiated (100 Gy) cell vaccine, or with 15 μg of tumour-derived hsp70. Vaccines were routinely given on the right flank whilst challenge was given 10–14 days later on the left flank. Tumour volume was measured two or three times weekly with callipers in two diameters. Mice were judged to possess a tumour when it was possible to measure a lump (>2 mm) and were killed when the tumours reached 15 mm in any diameter. Representative data from at least two separate experiments are given.

In vitro experiments

Spleens from killed mice that had previously received vaccination were removed, teased apart and the red cells were lysed with 0·87% ammonium chloride for 1 min. The resulting lymphocytes were washed and set up in culture (at 1 × 106/ml) with irradiated (50 Gy) syngeneic tumour cells at a ratio of 50 lymphocytes to one tumour cell. The medium used was RPMI-1640 supplemented with fetal calf serum, glutamine, penicillin and streptomycin as above, plus 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol. After 5 days, lymphocytes were harvested and tested for CTL activity by a colorimetric lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) -release assay (Promega, Madison, WI), following the maufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the log-rank test for survival and Student's t-test for mean values, both on prism software.

Results

Antigen expression

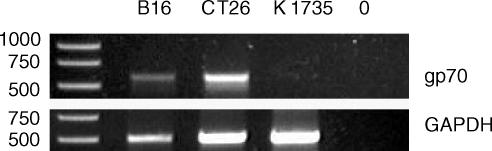

To confirm that the tumour cell lines expressed the gp70 antigen, RT-PCR was carried out with specific oligonucleotide primers (Fig. 1). A ubiquitous housekeeping gene (GAPDH) was amplified as a control to ensure successful RT-PCR and loading. Both CT26 and B16 expressed gp70, although the level in B16 was lower. K1735, serving as a negative control, did not express this antigen.

Figure 1.

Expression by tumours of gp70. Tumour lines were examined by RT-PCR for expression of gp70, with GAPDH used as a control. 0 = no DNA added.

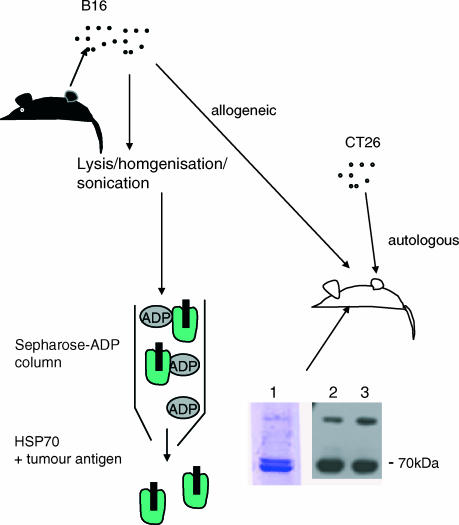

Extraction of hsp70

The 4 g of B16 tumour tissue, calculated to comprise approximately 109 tumour cells, was able to yield approximately 1 mg of purified hsp70 as determined by Bradford assay and SDS–PAGE/Western blot (Fig. 2). To monitor antigen processing in conjunction with hsp70 in more detail an ovalbumin transfectant of B16 was used. In addition, this transfectant was further transfected with the gene encoding inducible hsp70 using a retroviral construct with puromicin selection.

Figure 2.

Purification of hsp70 from tumours. The hsp70 was extracted from tumour cells and examined by SDS–PAGE and Western blotting. Lane 1 shows a typical SDS–PAGE of hsp70 extracted from B16. Lanes 2 and 3 show Western blots of hsp70 extracted from B16-OVA and B16-OVA-hsp70, respectively.

Vaccination

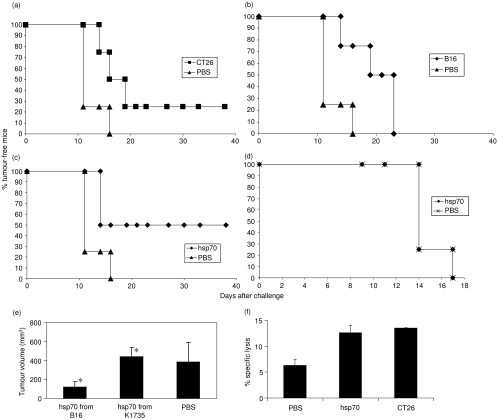

Vaccination of BALB/c mice with irradiated syngeneic CT26 tumour cells (1 × 106) routinely afforded protection from challenge with CT26 of between 20% (Fig. 3a) and 50% of mice. Vaccination of BALB/c mice with an equal number of B16 cells caused increased survival in these mice, although all mice succumbed eventually to tumour (Fig. 3b). When mice were vaccinated with B16-derived hsp70, 50% of mice remained tumour-free for the duration of the experiment (>40 days) (Fig. 3c). In contrast, vaccination of mice with hsp70 extracted from K1735 elicited no protection (none of four mice) against CT26 as shown by no inhibition in tumour growth (Fig. 3e) Moreover, mice vaccinated with hsp70 from B16 were not protected against a challenge with syngeneic RENCA cells (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3.

Immunity following vaccination. BALB/c mice (n = 4 per group) were vaccinated or were mock-vaccinated (PBS), and were subsequently challenged with a tumorigenic dose (2 × 105) of live CT26 cells (except d); % tumour-free survival is shown. Significance of protection: with (a) CT26 cells P = 0·064, (b) B16 cells P = 0·029, (c) hsp70 derived from B16 P = 0·031, (d) hsp70 derived from B16 and challenged with RENCA P = 1. (e) CT26 tumour volume on day 17 post-challenge, following vaccination with hsp70 from B16 compared to hsp70 from K1735 P = 0·02*. (f) Vaccination with hsp70 elicited similar CTL activity (% specific lysis at 50 : 1 effector to CT26 target ratio) to vaccination with CT26 cells.

CTL assay

To examine possible immune mechanisms, spleens of vaccinated mice were tested for CTL activity by 5-day restimulation followed by an LDH-release assay. Similar levels (approximately 12%) of CTL activity against CT26 targets were observed in both CT26 and hsp70-vaccinated groups, double that of PBS-treated mice (Fig. 3f). No activity against YAC-1 target cells was observed (not shown).

hsp70 re-presentation mechanisms

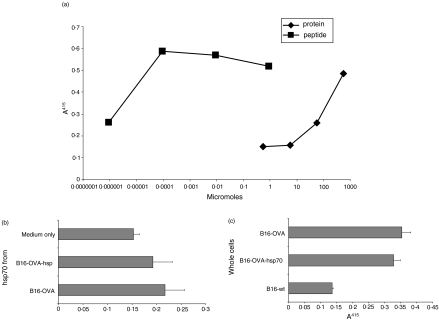

To examine antigen re-presentation in conjunction with hsp70 in more detail, hsp70 was extracted from an OVA-transfectant of B16. In an attempt to enhance the yield and function of hsp preparations, the B16-OVA was additionally transfected with inducible hsp70 (to give B16-OVA-hsp). The hsp70 was extracted from 4 g of tumour tissue as before and the yield from the B16-OVA-hsp (2 mg) was approximately double the yield from the B16-OVA (1 mg). The system for examining antigen re-presentation was recognition of the OVA peptide SIINFEKL on the surface of DC2.4 cells by B3Z T-cell hybridoma. Initial experiments demonstrated the sensitivity of the T cells to given peptide and OVA antigen concentrations, and demonstrated the sensitivity of the system and the range of peptide/antigen that could be recognized (Fig. 4a). Re-presentation of OVA peptide via hsp70 derived from B16-OVA and B16-OVA-hsp was of a similar magnitude (Fig. 4b), at a concentration of 0·57 μm, this being 1 log lower concentration than was required for OVA antigen. As has been described previously29 whole B16-OVA cells were recognized by the B3Z T-cell hybridoma but transfection with hsp70 did not significantly increase this recognition (Fig. 4c). Lastly, freeze–thaw lysates of B16-OVA applied to DC2.4 were not recognized by the T cells whether or not they were transfected with hsp70 (not shown).

Figure 4.

Antigen presentation to T cells by DC can be mediated via purified hsp70, but not direct presentation by tumour cells. (a) The sensitivity of the detection of OVA peptide SIINFEKL by B3Z T-cell hybridoma on DC2.4 was determined, and compared to presentation by processing whole OVA protein. A405 gives the β-galactosidase activity in T cells which is linked to their interleukin-2 expression/activation. (b) The hsp70 derived from B16-OVA or B16-OVA transfected with inducible hsp70 (B16-OVA-hsp) elicited recognition by B3Z. Likewise (c) B16-OVA and B16-OVA-hsp whole cells were recognized equally by B3Z T-cell hybridoma.

Discussion

The search for effective cancer immunotherapies has explored numerous vaccination approaches. Consistently, it has been found that autologous whole tumour cells, administered as an irradiated vaccine alone or with adjuvants, can elicit immune responses that are effective at controlling tumour growth. It remains a matter of debate whether tumour cells can directly prime T cells36 or whether tumour antigens are cross-presented by antigen-presenting cells.37 Clearly, both are probable, but hsp derived from tumours that chaperone tumour antigens must use the latter pathway. In an attempt to produce more practical and generic tumour vaccines, whole allogeneic tumour cell vaccines have been developed that probably possess antigens in common with the patient's cancer (usually of the same histological type). Since this approach has shown effects in preclinical and clinical studies, a logical next step could be to produce subunit tumour vaccines, that can be used for a range of patients, in the form of tumour-cell-derived hsp. This study aimed to support and examine such a principle.

The two murine tumour cell lines were used in this study because of reports of their expression of the murine retroviral envelope protein gp70.34 It is known that both lines express the whole gene and translate the protein (E. Jaffee, personal communication). However, because their sublines may have lost the antigen, expression in both lines was confirmed by RT-PCR, although B16 expresses considerably less gp70 than CT26.

The ability of a vaccine comprising allogeneic B16 cells to elicit a degree of protection in BALB/c mice against CT26 challenge also confirmed their antigenic cross-reactivity, and reduced protection compared to CT26 may be the result of its lesser expression of gp70. An allogeneic K1735 vaccine (which does not possess gp70) failed to induce immunity (data not shown) nor did hsp70 extracted from K1735 (Fig. 3e). Since efficacy was seen with the allogeneic cell line vaccine, it was logical to assume that hsp derived from the tumour would also be effective. Preparations of hsp70, derived in a simple process from B16 tumour material were indeed able to elicit protective immunity against CT26 challenge. It was possible to detect low but significant levels of anti-tumour CTL activity in the spleens of hsp70-vaccinated mice, that were of a similar magnitude to those detected in whole CT26-vaccinated mice (and to results published previously28), which is a moderately immunogenic vaccine. Both the lack of cytolytic activity against natural-killer-sensitive YAC-1 cells and the lack of protection against RENCA cells suggest that the lysis of CT26 cells was the result of CTL activity.

Being able to increase the yield of hsp obtained from tumour material would be of practical use in generating vaccine material. This was attempted by transducing B16-OVA cells with the inducible hsp70 gene, previously cloned from murine tumour cells after induction by thymidine kinase/ganciclovir gene therapy14 and subsequently inserted into a retroviral vector.32 The yield was indeed increased, but only by a modest two-fold. Nevertheless, this may be useful in vaccine production.

To attempt to dissect mechanisms of hsp70-mediated re-presentation of tumour antigen, hsp70 was extracted from B16-OVA and used in conjunction with DCs and a T-cell hybridoma. This hsp material was able to chaperone OVA antigen to DC to allow recognition by T-cell hybridomas at a molarity approximately 10-fold lower than achieved with OVA antigen. Thus hsp appeared to allow the antigens being chaperoned better access to the class I pathway than whole antigen, as has been described previously by other means.11 Since hsp70 is likely to chaperone a range of cell-derived proteins, the enhancement is substantial. It has been suggested that inducible hsp70 may have different chaperoning properties than constitutive hsp70 as a result of differing structural characteristics.38,39 This study, however, did not show a difference between the activity of hsp70 from hsp-transduced and non-transduced tumours. Another suggestion is that hsp70 over-expression by tumours may increase the tumours' ability to be recognized by antigen-specific T cells by increasing MHC expression or antigen processing.16 Here, over-expression of hsp70 did not increase whole tumour recognition by the T cells. Lastly, preliminary data (not shown) suggest that hsp70 from OVA-transfectants does not mediate re-presentation of a class II epitope to epitope-specific transgenic T cells, and this is the subject of current investigation

The present study demonstrates that hsp70 derived from tumour material of one mouse strain is able to generate immune-mediated protection against a tumour challenge in another mouse strain when the tumours have antigen in common. The hsp70 facilitates antigen cross-priming but increased intracellular expression does not enhance antigen presentation by the tumour cells or the cross-presentation of the tumour cell lysate. We propose that hsp70 derived from tumours of known antigenic makeup could be used as a more generic form of subunit tumour vaccine. Such material may also serve as a better source of multivalent antigen for pulsing ex-vivo DC for subsequent re-administration, than native antigen or tumour lysate.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Science Foundation Ireland and by the Irish Higher Education Authority. We are grateful to P. Dellabona, K. Rock and N. Shastri for allowing the use of cell lines.

References

- 1.Rosenberg SA. Progress in human tumour immunology and immunotherapy. Nature. 2001;411:380–4. doi: 10.1038/35077246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Der Bruggen P, Zhang Y, Chaux P, et al. Tumor-specific shared antigenic peptides recognized by human T cells. Immunol Rev. 2002;188:51–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson HL, Donermeyer DL, Ikeda H, et al. Eradication of established tumors by CD8+ T cell adoptive immunotherapy. Immunity. 2000;13:265–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chouaib S, Asselin-Paturel C, Mami-Chouaib F, Caignard A, Blay JY. The host–tumor immune conflict. from immunosuppression to resistance and destruction. Immunol Today. 1997;18:493–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermorken JB, Claessen AM, van Tinteren H, et al. Active specific immunotherapy for stage II and stage III human colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:345–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3539–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, Sun Y, Grabbe S, Dummer R, Burg G, Schadendorf D. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nat Med. 1998;4:328–32. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmerman JM, Singh G, Hermanson G, et al. Immunogenicity of a plasmid DNA vaccine encoding chimeric idiotype in patients with B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5845–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Srivastava P. Interaction of heat shock proteins with peptides and antigen presenting cells: chaperoning of the innate and adaptive immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blachere NE, Li Z, Chandawarkar RY, Suto R, Jaikaria NS, Basu S, Udono H, Srivastava PK. Heat shock protein-peptide complexes, reconstituted in vitro, elicit peptide-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and tumor immunity. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1315–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breloer M, Marti T, Fleischer B, von Bonin A. Isolation of processed, H-2Kb-binding ovalbumin-derived peptides associated with the stress proteins HSP70 and gp96. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1016–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<1016::AID-IMMU1016>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suto R, Srivastava PK. A mechanism for the specific immunogenicity of heat shock protein-chaperoned peptides. Science. 1995;269:1585–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7545313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:435–42. doi: 10.1038/74697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melcher A, Todryk S, Hardwick N, Ford M, Jacobson M, Vile RG. Tumor immunogenicity is determined by the mechanism of cell death via induction of heat shock protein expression. Nat Med. 1998;4:581–7. doi: 10.1038/nm0598-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Todryk S, Melcher AA, Hardwick N, Linardakis E, Bateman A, Colombo MP, Stoppacciaro A, Vile RG. Heat shock protein 70 induced during tumor cell killing induces Th1 cytokines and targets immature dendritic cell precursors to enhance antigen uptake. J Immunol. 1999;163:1398–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells AD, Rai SK, Salvato MS, Band H, Malkovsky M. Hsp72-mediated augmentation of MHC class I surface expression and endogenous antigen presentation. Int Immunol. 1998;10:609–17. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark PR, Menoret A. The inducible Hsp70 as a marker of tumor immunogenicity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:121–5. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0121:tihaam>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang XY, Li Y, Manjili MH, Repasky EA, Pardoll DM, Subjeck JR. Hsp110 over-expression increases the immunogenicity of the murine CT26 colon tumor. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2002;51:311–19. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0287-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava PK, Menoret A, Basu S, Binder RJ, McQuade KL. Heat shock proteins come of age: primitive functions acquire new roles in an adaptive world. Immunity. 1998;8:657–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenberg SA. Cancer vaccines based on the identification of genes encoding cancer regression antigens. Immunol Today. 1997;18:175–82. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)84664-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsueh EC, Essner R, Foshag LJ, et al. Prolonged survival after complete resection of disseminated melanoma and active immunotherapy with a therapeutic cancer vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4549–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.01.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toes RE, Blom RJ, van der Voort E, Offringa R, Melief CJ, Kast WM. Protective antitumor immunity induced by immunization with completely allogeneic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3782–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight BC, Souberbielle BE, Rizzardi GP, Ball SE, Dalgleish AG. Allogeneic murine melanoma cell vaccine. A model for the development of human allogeneic cancer vaccine. Melanoma Res. 1996;6:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00008390-199608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffee EM, Hruban RH, Biedrzycki B, et al. Novel allogeneic granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-secreting tumor vaccine for pancreatic cancer: a phase I trial of safety and immune activation. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:145–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castelli C, Ciupitu AM, Rini F, Rivoltini L, Mazzocchi A, Kiessling R, Parmiani G. Human heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes specifically activate anti-melanoma T cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noessner E, Gastpar R, Milani V, et al. Tumor-derived heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes are cross-presented by human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:5424–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Todryk SM, Birchall LJ, Erlich R, Halanek N, Orleans-Lindsay JK, Dalgleish AG. Efficacy of cytokine gene transfection may differ for autologous and allogeneic tumour cell vaccines. Immunology. 2001;102:190–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Todryk SM, Tutt AL, Green MH, Smallwood JA, Halanek N, Dalgleish AG, Glennie MJ. CD40 ligation for immunotherapy of solid tumours. J Immunol Meth. 2001;248:139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00349-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ah SA, McLean CS, Bourshell ME, et al. Preclinical evaluations of whole cell vaccines for prophylaxis and therapy using disabled infectious single cycle-herpes simplex virus vector to transcribe cytokine genes. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1663–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bellone M, Cantarella D, Castiglioni P, et al. Relevance of the tumor antigen in the validation of three vaccination strategies for melanoma. J Immunol. 2000;165:2651–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen Z, Reznikoff G, Dranoff G, Rock KL. Cloned dendritic cells can present exogenous antigens on both MHC class I and class II molecules. J Immunol. 1997;158:2723–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shastri N, Gonzalez F. Endogenous generation and presentation of the ovalbumin peptide/Kb complex to T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:2724–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gough MJ, Melcher AA, Ahmed A, et al. Macrophages orchestrate the immune response to tumor cell death. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7240–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang AY, Gulden PH, Woods AS, et al. The immunodominant major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted antigen of a murine colon tumor derives from an endogenous retroviral gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9730–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng P, Menoret A, Srivastava PK. Purification of immunogenic heat shock protein 70-peptide complexes by ADP-affinity chromatography. J Immunol Meth. 1997;204:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ochsenbein AF, Sierro S, Odermatt B, et al. Roles of tumour localization, second signals and cross priming in cytotoxic T-cell induction. Nature. 2001;411:1058–64. doi: 10.1038/35082583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang AY, Golumbek P, Ahmadzadeh M, Jaffee E, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. Role of bone marrow-derived cells in presenting MHC class I-restricted tumor antigens. Science. 1994;264:961–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7513904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menoret A. Immunological significance of hsp70 in tumour rejection. In: Robins RA, Rees RC, editors. Cancer Immunology. Dardrecht: Kluwer; 2001. pp. 157–69. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Callahan MK, Chaillot D, Jacquin C, Clark PR, Menoret A. Differential acquisition of antigenic peptides by Hsp70 and Hsc70 under oxidative conditions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33604–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]