Abstract

Natural killer (NK) T lymphocytes are thought to act as regulatory cells directing early events during immune responses. Murine NKT cells express inhibitory receptors of the Ly49 family. These receptors have a well-established and crucial role in modulating NK cell activities, but their physiological role in regulating NKT cells is not well understood, nor is the influence of major histocompatibility (MHC) ligands on endogenous Ly49 expression. We have further investigated how the expression of inhibitory NK receptors is regulated on NKT cells, and demonstrate a non-random expression of ligated Ly49 molecules on CD1d-restricted NKT cells. The nature of the T-cell receptor on the NKT cell crucially determines the profile of expressed Ly49 isoforms. Further, we show that MHC class I ligands efficiently modulate the expression levels of the inhibitory receptors, and the frequencies of cells positive for the Ly49 members. In addition, we find a several-fold increase in Ly49C/I-expressing NKT cells in adult thymus, apparently independent of MHC class I molecules. Abundant expression of Ly49 receptors on NKT cells, and the striking differences found in Ly49 isoform patterns on NKT-cell subsets differing in T-cell receptor expression, suggest that the pattern of Ly49 expression is tuned to fit the T-cell receptor and to emphasize further a role for these receptors in NKT immunity.

Introduction

The natural killer (NK) T lymphocytes share surface markers and functional capacities with both T lymphocytes and NK cells, and can be identified in the mouse by coexpression of the T-cell receptor (TCR) αβ and the NK1.1 surface marker. Most NKT cells are dependent on the non-classical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-like molecule CD1d.1–3 NKT cells make up a minor T-lymphocyte subset in spleen and lymph nodes but are enriched among T cells found in bone marrow, liver and among mature T cells in the thymus. CD1d-restricted NKT cells express the co-receptor CD4 or are CD4− CD8− (double negative, DN). NKT cells respond rapidly and potently to activation, and they are thought to have a crucial role as early regulators of immune responses. They have been shown to participate in the regulation of autoimmune reactions, tumour rejection and during infections with intracellular organisms and parasites.4 The CD1 molecules present lipids and glycolipids to T lymphocytes, but the natural activating ligands for CD1d-restricted NKT cells are still largely unknown. CD1d-restricted T cells are able to react to CD1d in vitro in the absence of added ligands,5,6 thus it is possible that NKT cells can respond to endogenous CD1d under certain circumstances also in vivo.

Some murine NKT cells express inhibitory NK cell receptors belonging to the Ly49 receptor family.7–12 Functional Ly49 members have not been found in humans, but are used in the mouse analogously to killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) expressed by human NK cells. Different isoforms within the Ly49 family bind different allelic forms of classical MHC class I molecules (reviewed in ref. 13). Upon MHC class I binding, most Ly49 receptors on NK cells mediate inhibitory signals, counteracting stimulatory events (reviewed in ref. 14) and preventing the NK cell from activation or killing of a MHC class I+ target cell. On NK cells the Ly49 members are expressed oligoclonally on overlapping subsets of cells, and more than one receptor are generally found on a single NK cell. Which Ly49 receptors a certain NK cell expresses is thought to result from a random or sequential initiation of expression of Ly49 isoforms, modulated by the surrounding MHC class I ligands.15,16 The proposed result of this process is that each mature NK cell expresses at least one Ly49 receptor with a cognate MHC class I ligand present in the environment.13,17 The role of Ly49 inhibitory receptors on NKT cells is unclear, although several groups have demonstrated that they are functional. They have been suggested to control autoreactivity, and it was shown that engagement of Ly49 receptors can inhibit NKT-cell proliferation,11,18 cytokine production12 and cytotoxic activity8 and furthermore, that transgenic Ly49 expression could influence the TCR repertoire of NKT and T cells.9,19,20

Two types of CD1d-restricted NKT cells can be distinguished by the TCR repertoires they carry. A large fraction of NKT cells utilize a canonical TCR comprised of a conserved Vα14-Jα18 gene rearrangement combined preferentially with Vβ8 but also Vβ2 or Vβ7.21 The other subset of CD1d-restricted NKT cells utilizes a more diverse TCR repertoire6,22–25 which was recently found to include sets of cells using less common, recurrent TCR different from the Vα14-type.26 While inhibitory receptors on NK cells are thought to counteract positive signals from a diverse set of activating surface receptors,27 Ly49 molecules on NKT cells may instead balance activating signals through the TCR. NKT cells carrying distinct TCR may therefore differ in their requirements for inhibitory Ly49 receptor expression. In the present report we show that endogenous Ly49 receptors are not randomly distributed on NKT cells. The specificity of the TCR appears to set rules for Ly49 receptor expression on the NKT cells, and the pattern of Ly49 isoforms expressed can be strongly skewed by both MHC-dependent and -independent mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 (B6), B10.D2/nSnJ (the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) and 24αβ TCR transgenic mice28 were bred and maintained in a clean conventional animal facility at Lund University. The 24αβ TCR transgenic mice (H2β) had been backcrossed three to six generations (with the same Ly49 expression pattern) on to a B6 genetic background. Where indicated, 24αβ mice had been crossed with B10.D2/nSnJ mice and offspring carrying the transgenic 24αβ TCR were used for experiments. D8 transgenic mice made on a B6 background29 and mice deficient for Kb and Db (K0D0 mice)30 backcrossed six generations on B6 background were maintained in a clean conventional animal facility at MTC, Karolinska Institute. Unless indicated, the mice used in the experiments were between 10 and 16 weeks old.

Cell preparation and enrichment of DN T cells

To enrich for CD4+ and DN T cells, spleen cells were depleted of red blood cells by lysis and of B cells by a method described elsewhere.11 The remaining cells were depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ cells using GK1.5 (anti-CD4) and YTS169.4 (anti-CD8α) antibodies together with anti-ratκ-microbeads, or anti-CD4 and -CD8 beads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch, Germany) using a magnetic antibody cell sorting magnet (Miltenyi Biotech) to further enrich for DN T cells. The resulting population contained 15–20% TCRβ+ cells, a total of 0·5% contaminating CD4+ or CD8+ cells and 5–10% B220+ immunoglobulin M (IgM)+ cells. NKT cells were enriched from the thymus by depleting heat stable antigen (HSA)+ cells as previously described.11

Flow cytometry

Before staining the cells were incubated with the 2.4G2 (anti-CD16/CD32) antibody to block non-specific binding. The following monoclonal antibodies or second-step conjugates were bought from PharMingen (San Diego, CA): A1-biotin (anti-Ly49A), Vα3.2-biotin, Vβ9-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), TCRβ-CyChrome, TCRβ-allophycocyanin (APC), TCRβ-FITC, CD3ε-peridinin chlorophyll-a protein (PerCP), CD8α-PerCP, CD4-PerCP, CD4-biotin, B220-phycoerythrin (PE), NK1.1-PE, NK1.1-APC, streptavidin-APC, interleukin-2 (IL-2) -PE, IL-4-PE, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) -PE and isotype controls. Streptavidin-PE was obtained from Southern Biotechnology Associates Inc. (Birmingham, AL). CD8α-PE, IgM-FITC and goat F(ab′)2 anti-rat IgG(H + l)-FITC were from Caltag Laboratories (San Francisco, CA). Streptavidin-Red613 was obtained from Gibco BRL (Life Technologies, Paisley, UK). A1 (anti-Ly49A), 4D11 (anti-Ly49G2) and 5E6 (anti-Ly49C/I) coupled to FITC or biotin, GK1.5-FITC, 53.5.81 (anti-CD8α), RR3.16 (anti-Vα3.2) and MR10.2 (anti-Vβ9) were purified and biotinylated or FITC-conjugated according to standard procedures. GK1.5, RR3.16, MR10.2, 5E6 and streptavidin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) were conjugated with Cy5 using a labelling kit from Amersham Life Science (Little Chalfont, UK). CD1d-tetramers loaded with α-galactosyl-ceramide (Kirin Brewery Co., Gunma, Japan), or unloaded control tetramers, were produced and used for immunofluorescence as described previously.31 The stained cells were analysed by three- or four-colour flow cytometry on a FACSort or a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) using cellquest software.

Results

NKT cells showed a tissue-specific expression pattern of Ly49 isoforms

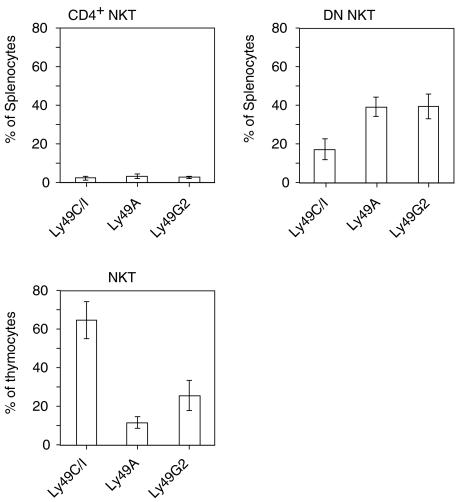

Analysis has shown that the proportion of splenic NKT cells (defined as TCRβ+ NK1.1+ or CD4+ NK1.1+ cells) positive for a given Ly49 receptor was lower in mice expressing the cognate MHC class I ligand, than in mice lacking ligands.9,11 This suggested a negative effect on Ly49 expression levels, and/or on the NKT cells carrying engaged Ly49 receptors, by the presence of the MHC ligand. In apparent contrast to this, we and others have observed that Ly49 expression by thymic NKT cells differed from NKT cells in the spleen and bone marrow.11,12 In B6 mice (H2β) ligands for Ly49C and Ly49I are present (the monoclonal antibody 5E6 binds both Ly49C and Ly49I).32,33 Ly49G2 lacks cognate MHC class I ligands, while Ly49A was recently found to have a weak ligand in B6 mice (reviewed in ref. 13). To analyse Ly49 expression on spleen cells, DN and CD4+ NKT cells were investigated separately since splenic CD4+ cells were essentially negative for Ly49 receptors.11 In contrast, in the thymus DN and CD4+ NKT cells have very similar Ly49 surface profiles.11 Therefore, data from this organ are consistently shown below for total thymic NKT cells. In agreement with previous results, Ly49C/I+ NKT cells were three- to six-fold more frequent than Ly49A+ or Ly49G2+ NKT cells in B6 thymus (Fig. 1 and ref. 11), despite the presence of strong MHC class I ligands for Ly49C/I but not for the latter receptors. The opposite pattern was observed in the spleen, where Ly49G2+ and Ly49A+ DN NKT cells were more common than Ly49C/I+ NKT cells. Thus, in contrast to the periphery, NKT cells carrying Ly49C/I were abundant in the B6 thymus.

Figure 1.

Organ- and subset-specific Ly49 expression on NKT cells. Spleen cells were depleted of B cells and stained for CD4, NK1.1 and Ly49 expression for analysis of CD4+ NK1.1+ T cells, and further depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ cells before staining with antibodies to TCRβ, NK1.1 and Ly49 for analysis of DN NKT cells. Thymocytes were depleted of HSA+ cells before staining with antibodies to TCRβ, NK1.1 and Ly49 for analysis of total thymic NK1.1+ TCRβ+ cells. The frequencies of Ly49+ cells among splenic CD4+ NKT (CD4+ NK1.1+) cells (upper left panel), splenic DN NKT (NK1.1+ TCRβ+) cells (upper right panel) and thymic NKT (NK1.1+ TCRβ+) cells (lower panel) is shown (mean ± SD, n = 3 to n = 7 B6 mice).

Ly49C/I+ NKT cells included a high proportion of Vβ8.2+ cells.

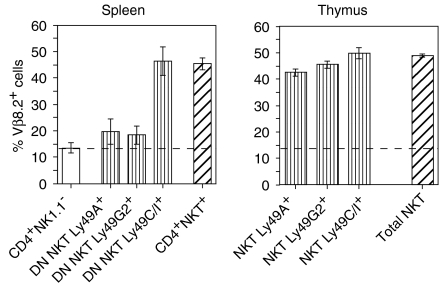

In the thymus the Vα14-type of TCR type dominates the NKT population and is expressed by both CD4+ and DN NKT cells, while a lower proportion of the splenic DN NKT-cell subset utilizes this restricted TCR repertoire (refs 31,34 and our unpublished data). This suggested that the high Ly49C/I expression may correlate with the use of the Vα14-type TCR. To investigate a possible TCR : Ly49 relationship, we first analysed the presence of the invariant TCR indirectly by determining the frequency of Vβ8.2+ cells, as the canonical Vα14 TCR α-chain preferentially combines with this Vβ segment. NKT subsets expressing different Ly49 receptors were compared (Fig. 2). For reference we also examined CD4+ NK1.1+ and conventional CD4+ NK1.1− T cells in the spleen as well as total thymic NKT cells. In the spleen, Vβ8.2 usage within the Ly49C/I+ DN T-cell subset was markedly elevated, and was as high as among thymic NKT cells and splenic CD4+ NKT cells. In contrast, Vβ8.2+ expression among Ly49A+ or Ly49G2+ DN NKT cells was comparable to that found for conventional CD4+ NK1.1− cells. In thymus the Vβ8.2 usage by all Ly49 subsets was high, and similar to that of the total thymic NKT population, reaching around 45%. Simultaneous staining of thymic NKT cells for Ly49C/I and Ly49G2 or Ly49A showed that 90% and 80%, respectively, of Ly49G2+ and Ly49A+ cells were found within the larger Ly49C/I population (data not shown, and Figs 3 and 4 below). Thus, in both spleen and thymus Ly49C/I-expressing NKT cells had a high proportion of Vβ8.2+ cells, suggesting that a majority of the cells were of the Vα14 type.

Figure 2.

Vβ8.2 usage within Ly49 subsets of NKT cells. Vβ8.2 usage by Ly49 subsets of splenic DN NKT cells (left panel) and thymic NKT cells (right panel) from B6 mice was determined by flow cytometry. Spleen cells had been depleted of B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ cells (DN cells) and stained with antibodies to TCRβ, NK1.1, Ly49 and Vβ8.2. NK1.1+ TCRβ+ Ly49+ (A, G2, or C/I) cells were gated and analysed for Vβ8.2 expression. For analysis of the control CD4+ NK1.1− and CD4+ NK1.1+ subsets, B-depleted spleen cells were stained for CD4, NK1.1, Ly49 and Vβ8.2 expression. Thymocytes were depleted of HSA+ cells before being stained and analysed as described for DN spleen cells above. Values represent percentage of Vβ8.2+ cells (mean ± SD, n = 3) within the indicated populations. The frequencies of Vβ8.2+ cells among CD4+ NK1.1+ and CD4+ NK1.1− cells in the spleen, and of total NKT (NK1.1+ TCRβ+) cells in thymus were included for comparison. The dotted line represents Vβ8.2 usage by splenic CD4+ NK1.1− cells.

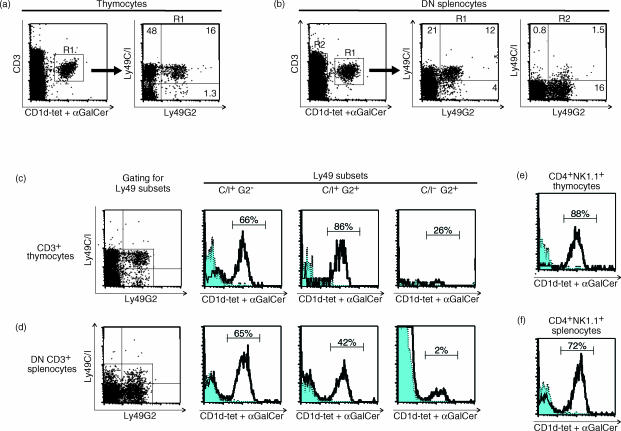

Figure 3.

Predominance of the α-GC-CD1d-tetramer-binding canonical NKT-cell TCR among Ly49C/I+, but not L49G2+C/I− NKT cells. B6 thymocytes (a,c) or spleen cells depleted of CD4+, CD8+ and Ig+ cells (b, d) were stained with αGC-loaded or control CD1d tetramers and for the expression of CD3 and Ly49 markers. CD1dαGC-tetramer binding thymocytes (a) and DN splenocytes (b), as gated in the left panels, were displayed for Ly49C/I and -G2 expression (right panels). Ly49+ subsets of CD3+ thymocytes (c) and CD3+ DN splenocytes (d) were gated (dot plots to the left) and displayed for αGC-loaded (solid lines with empty histograms) or control (dotted lines with shaded histograms) CD1d-tetramer-binding as indicated in the histograms. The fractions of tetramer-binding thymic (e) and splenic (f) CD4+ NK1.1+ cells are shown as controls. The experiment is representative of four (thymus) or two (spleen) performed.

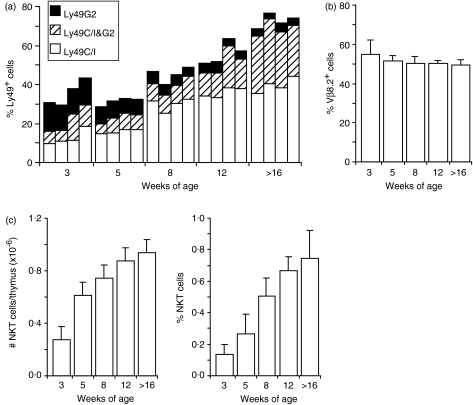

Figure 4.

Age-dependent specific increase in Ly49C/I-expressing thymic NKT cells. (a) Thymocytes from B6 mice of the indicated ages were stained for CD3 (used instead of TCRβ for technical reasons when simultaneous stains of Ly49C/I and G2 were performed), NK1.1, Ly49C/I and Ly49G2. The bars indicate the sizes of Ly49-expressing subsets among NKT (CD3+ NK1.1+) cells. Ly49G2 only – black section of the bars, coexpression of Ly49G2 and C/I – hatched section, Ly49C/I only – white section. Each bar represents values from one mouse. Results from parallell stainings (two mice per age group) for TCRβ, NK1.1 and either of Ly49C/I or Ly49G2 (data not shown) differed on average less than 6% from the values in (a) for each Ly49 stain at all ages excluding a significant influence by TCRγδ T cells. (b, c) The same cells were stained for TCRβ, NK1.1 and Vβ8.2. The degree of Vβ8.2 expression among TCRβ+ NK1.1+ cells (b), and (c) the numbers per thymus (left panel) and frequencies (right panel) of TCRβ+ NK1.1+ cells are shown as mean and SD of the mice used in (a).

Restricted expression of Ly49C/I to NKT cells using the canonical α-galactosyl-ceramide-binding CD1d-restricted TCR

NKT cells which express the canonical Vα14-type TCR are specific for the synthetic ligand α-galactosyl-ceramide (αGC) presented on CD1d35 and can be directly visualized using fluorescent αGC-loaded CD1d-tetramers (CD1dαGC-tet).31 On the population stained with the αGC-loaded tetramer, Ly49C/I was expressed at a four-fold higher proportion than Ly49G2 in the thymus (Fig. 3a) and two-fold higher on the CD1dαGC-tet+ DN splenic cells (Fig. 3b). CD1dαGC-tet− DN CD3+ cells in the spleen (Fig. 3b, gate R2 shown in the right panel), on the other hand, contained very few Ly49C/I+ cells but had a distinct population of Ly49G2+ cells (which were mostly NK1.1+, not shown). Consistent with this, Ly49C/I+ T cells contained a high proportion of αGC-tetramer positive cells, which was seen in both the Ly49C/I+G2− and Ly49C/I+G2+ subsets. This was true both in the thymus (Fig. 3c) and among DN splenocytes (Fig. 3d). Strikingly, the splenic Ly49C/I−G2+ subset was essentially devoid of CD1dαGC-tet-binding cells. Taken together the results showed a high expression of Ly49C/I on Vα14-type NKT cells, while non-Vα14 NKT cells infrequently displayed this receptor but were positive for Ly49G2.

Age-related several-fold increase of Ly49C/I expression on thymic NKT cells

We noted that in young adult mice Ly49 expression appeared on fewer thymic NKT cells than in older mice, and the pattern of Ly49-isoform skewing was less extreme. This indicated an age-related change in Ly49 expression. We therefore analysed mice of different ages, from 3 weeks old to adulthood. In 3-week-old mice, Ly49G2-expressing NKT cells were generally more frequent than those having -C/I, and the relative proportion of Ly49C/I to -G2-positive cells was similar to that found on, for example, NK cells in adult B6 mice. At this age, 30–40% of NKT cells expressed at least one of these Ly49 receptors (G2 + C + I, Fig. 4a). This Ly49-expressing subset of NKT cells was augmented with age to 70–80% at 16 weeks, at the same time as the Ly49C/I fraction became increasingly dominant (white + hatched section of bars in Fig. 4a). During this time Ly49C/I expression changed from 15–30% to around 70% among NKT cells, while the fraction of cells expressing Ly49G2 but not Ly49C/I was reduced from 13–15% to less that 5%. During this time the proportion of Vβ8.2+ NKT cells remained the same (Fig. 4b), indicating that the representation of the canonical Vα14 NKT subset was constant, while total thymic NKT cells increased in frequency as well as in absolute numbers (Fig. 4c). Thus, there was a clear age-dependent skewing of Ly49 isoforms on thymic NKT cells.

MHC Ia (K, D) -dependent and -independent forces skewed the pattern of Ly49 receptors on canonical NKT cells

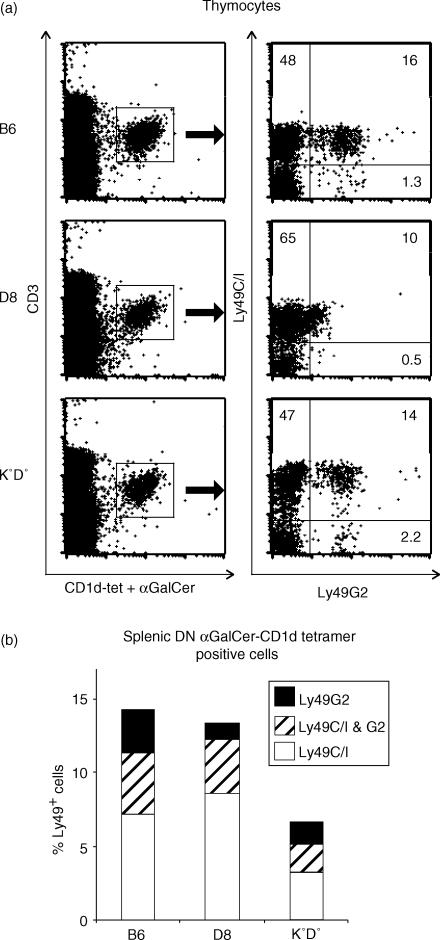

The skewed pattern of Ly49 receptor expression on adult thymic NKT cells could be dictated by Ly49–MHC ligand interactions. To investigate such effects we analysed Ly49 receptors in two types of mice with altered ligand expression (Fig. 5). D8 mice are transgenic for the MHC class I Dd molecule which binds both Ly49C/I and Ly49G2, resulting in an increased ligand density for these receptors. Mice lacking conventional MHC class I molecules (K0D0 mice30) should not have any ligands for the Ly49 receptors analysed. In D8 mice, expression of the transgenic Dd ligand resulted in decreased frequencies of Ly49G2+ cells among CD1dαGC-tet+ thymocytes (Fig. 5A), possibly as a consequence of receptor internalization, and the positive cells detected in these mice had greatly reduced levels of the marker. This showed that the presence of a MHC ligand could reduce the expression of the bound Ly49 molecule. In contrast, Ly49C/I expression was not detectably influenced by the transgene but remained high. A similar Ly49 receptor skewing was also seen on TCRβ+ NK1.1+ thymocytes in BALB/c mice (H2d) congenic for the NK-locus from B6 mice (data not shown). In K0D0 mice devoid of conventional MHC class I molecules, the proportion of CD1dαGC-tet-binding thymocytes displaying Ly49C/I was unchanged, although the level of Ly49C/I expressed per cell was increased. The same was found in mice deficient for the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) (data not shown). DN splenic CD1dαGC-tet+ cells from the different mice showed similar Ly49 expression, although as also seen in Fig. 3(b) compared with Fig. 3(a), the overall frequencies of Ly49 expression were lower in this population, and the skewing towards Ly49C/I was less extreme. Thus, the skewing of Ly49-isoform pattern on thymic NKT cells appeared independently of classical MHC class I ligands.

Figure 5.

Elevated expression of Ly49C/I on CD1dαGC-tet-binding T cells independent of MHC class Ia molecules. Thymocytes (a) and spleen cells (b) of B6, D8 and K0D0 mice were stained as in Fig. 3. (a) The left set of dot plots show gating for the CD1dαGC-tet+ CD3+ thymocytes and the panels to the right show the expression of Ly49C/I and -G2 on the gated populations. (b) The bars indicate the sizes of Ly49-expressing subsets among DN CD1dαGC-tet+ spleen cells from the indicated mice. Ly49G2 only – black section of the bars, coexpression of Ly49G2 and C/I – hatched section, Ly49C/I only – white section. The data shown are from one of two experiments performed with similar results.

Distinct expression of Ly49 molecules on non-canonical CD1d-restricted NKT cells modulated by MHC

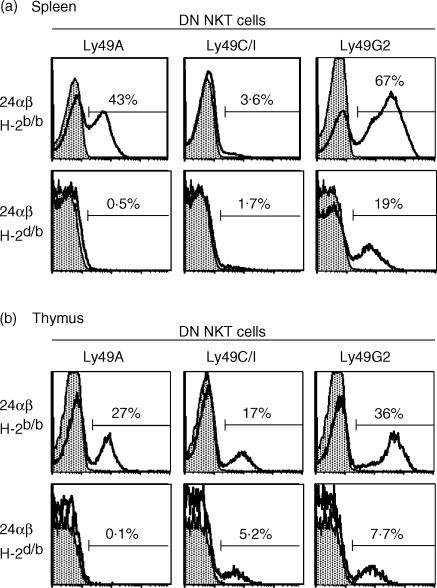

It may be assumed that the expression of inhibitory Ly49 receptors is adjusted to balance positive signals in NKT cells, just like in NK cells, and that the TCR is a major triggering receptor on NKT cells. If so, different TCR within the NKT-cell population may have distinct requirements for negative regulation by Ly49 molecules. This would result in differences in Ly49 expression correlating with TCR, as individual Ly49 receptors have unique specificities and affinities to the class I ligands in a given MHC environment. It is known that a proportion of DN NKT cells in the spleen is CD1d-independent. Therefore, to investigate a homogenous CD1d-restricted NKT-cell population with a TCR other than the Vα14-type, we utilised the 24αβ mouse28 which carries a transgenic CD1d autoreactive TCR (Vα3·2/Vβ9) of the diverse type, back crossed to the B6 background. In transgenic 24αβ mice carrying H2b, NKT cells in the spleen had very low frequencies of Ly49C/I+ cells while Ly49A+ and Ly49G2+ 24αβ NKT cells were abundant (11 and Fig. 6A), very similar to the pattern found on CD1dαGC-tet negative DN NKT cells in B6 mice (gate R2 in Fig. 3B). Transgenic Ly49C/I+ NKT cells were present in the thymus, but the fractions of Ly49A+ and Ly49G2+ cells were higher. 24αβH2b mice were crossed with B10.D2 mice (H2d) to express the transgenic TCR in the presence of MHC class I ligands for all three tested Ly49 receptors (H2b/d). DN 24αβ NKT cells in H2b/d mice contained essentially no or very few cells expressing Ly49A and Ly49C/I (Fig. 6, lower panels of A and B) and the frequency of Ly49G2+ 24αβ NKT cells was severely reduced compared to 24αβH2b/b mice. In contrast, high levels of Ly49C/I was found on a substantial fraction of these cells in 24αβ mice deficient for TAP (11 and data not shown), strongly suggesting a negative regulation by MHC class I ligands. Thus, similar to what has been found for the splenic DN NKT-cell population in B6 mice, engaged Ly49 receptors were under represented on 24αβ transgenic NKT cells both in H2b and H2d environments. Taken together, these results show first that the expression of endogenous Ly49 inhibitory receptors on CD1d-restricted NKT cells of the non-canonical as well as the Vα14-type (see above) could be reduced by MHC ligands. Second, the pattern of surface Ly49 receptors varied substantially between NKT cells displaying different TCR.

Figure 6.

MHC class I ligands influence the Ly49 expression on NKT cells using a CD1d-autoreactive transgenic non-Vα14 TCR. B-cell-depleted spleen cells or thymocytes were stained for CD4 and CD8 (using the same fluorochrome), TCRβ, NK1.1 and Ly49. DN TCRβ+ NK1.1+ cells (which all carry the transgenic TCR) were gated and are displayed for Ly49 expression. The histograms show Ly49A, Ly49C/I and Ly49G2 expression by gated DN NKT cells from a 24αβ mouse expressing MHC class I of H2b/b or H2d/b as indicated. (a) Ly49 expression on gated DN NKT cells from B-cell-depleted splenocytes. (b) Ly49 expression on gated DN NKT cells from thymus. Thick lines and white histograms indicate Ly49 staining, and thin lines and grey histograms show isotype control stains. The frequencies of Ly49+ 24αβ DN NKT cells in both organs analysed were markedly reduced in the presence of a cognate MHC class I ligand.

Discussion

The natural activation and regulation of NKT cells during immune responses is not well understood. In this report we have further investigated the regulation of expression of inhibitory NK receptors on NKT cells, and asked whether the specificity of the TCR on the NKT-cell influences the display of endogenous receptors of the Ly49-family. We found a non-random expression of ligated Ly49 molecules on CD1d-restricted NKT cells, which was influenced by the TCR used by the NKT cell. The expression levels of the Ly49 receptors, and the frequencies of positive cells could be down-regulated by MHC class I-ligands. Furthermore, a several-fold increase in Ly49C/I-expressing thymic NKT cells occurred between 3 weeks and 4 months of age apparently regardless of MHC class I-ligands.

On NK cells the inhibitory NK receptors, including the Ly49 molecules, are thought to counteract constitutive activating signals through several surface receptors. Among these are 2B4 (CD244), CD28, CD69 and CD2, as well as a diversity of NK receptors associated with adaptor proteins containing intracellular immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activating motifs (ITAM).27 Thus, NK cells are kept silent under normal conditions by appropriate levels and combinations of ligated inhibitory receptors. There is a delicate adjustment of the extent and level of Ly49 expression on NK cells modulated by the MHC, to maintain a sum of negative signals thought to fit the strength of positive signals from the normal environment. The TCR is likely to be a major positively signalling receptor complex on NKT cells. The NKT cells bearing the canonical Vα14-TCR, as well as NKT cells with other CD1d-restricted TCR, appear to have a relatively high reactivity to endogenous CD1d, as T-cell hybridomas made from these cells often show autoreactivity.5,6,23 Potentially autoreactive NKT cells may require control by negative signals through engaged inhibitory receptors such as the Ly49 molecules, analogous to what has been proposed for NK cells. Inhibitory Ly49 receptors are functional on NKT cells, as demonstrated by several groups, and their signalling can interfere with intracellular signals that drive T- or NKT-cell selection,9,19,20 activation and/or proliferation.8,11,12,18,36,37 Evidence for MHC class I-binding inhibitory receptors as regulators of physiological NKT-cell autoreactivity was recently presented by Ikarashi and co-workers.38 Thus, TCR reactivity to CD1d may be a major determinant of inhibitory receptor expression on NKT cells. If so, cells sharing TCR specificity may have a homogeneous expression of ligated Ly49 receptors in a given MHC environment. This is consistent with our results which demonstrate distinct patterns of Ly49 expression on NKT cells with different TCR. NKT cells make up a heterogeneous population. TCRαβ T cells expressing the NK1.1 antigen are not all CD1d-restricted, and it is known that a proportion of DN splenic NKT cells are CD1d-independent. While the canonical αGC-reactive NKT cells can be identified through their conserved TCR and reactivity, CD1d-restricted T cells with non-Vα14 TCR cannot be identified by surface markers. We therefore included analysis of mice expressing a transgenic CD1d-restricted non-Vα14 TCR. Interestingly, the TCR transgenic 24αβ NKT cells had a very similar Ly49 expression pattern to the splenic DN CD1dαGC-tet-negative NKT-cell population in B6 mice, which contrasted to the display of Ly49 isoforms by cells using the CD1dαGC-tet binding Vα14 TCR.

Our data suggest that two distinct influences besides TCR specificity influence Ly49 isotype expression on NKT cells. First, as on NK cells, the expression of Ly49 receptors could be down-modulated by their MHC class I ligands both on NKT cells with the canonical and those with the diverse TCR. Compared to the effects seen on NK cells, the frequencies on NKT cells were more strongly influenced.11,39 This had been suggested from previous data, but is more clearly visualized in the present report by our further analysis of NKT-cell populations with homogeneous TCR. Second, we demonstrate a three- to four-fold age-dependent increase in Ly49C/I expression on canonical NKT cells, independent of conventional MHC ligands. In general, the presence of ligands decreases the fraction of NK and NKT cells displaying the corresponding Ly49-receptor. On the other hand, appropriate up-regulation of ligated inhibitory markers is thought to be required for NK cell maturation.39 We cannot exclude the existence of an unknown, conserved ligand which may bind Ly49C/I and increase the proportion of canonical Vα14 NKT cells expressing Ly49C/I. Alternatively, the high Ly49C/I expression on Vα14NKT cells is ligand independent. A similar MHC-independent skewing of Ly49 isoforms has, to our knowledge, not been described before.

It was recently demonstrated that the expression of NK markers, including the Ly49 family of molecules, is a late event in NKT-cell development.10,40,41 CD1dαGC-tet+ cells leave the thymus as NK1.1− Ly49− cells and up-regulate these markers in peripheral tissues, or in the thymus for the cells that remain in this organ.41,42 These results make it unlikely that endogenous Ly49 receptors influence TCR selection of NKT cells. Recent thymic migrant NKT cells may initiate Ly49 expression shortly upon arrival in a tissue so that it can be tested against surrounding MHC class I ligands. In situ matching of appropriate levels of ligated inhibitory receptors to the TCR on each cell would ensure a fine tuned control of autoreactivity. Such a mechanism would give one explanation to the varying patterns of Ly49 receptors on NKT cells found in different tissues.11,12 Interestingly, in contrast to the mature NK population, some peripheral NKT-cell subsets of adult mice may be negative for Ly49 on the surface. The splenic and liver CD4+ NKT-cell subsets (Fig. 1 and ref. 11), of which around 70% bind the CD1dαGC-tet (Fig. 3F and ref. 31), were essentially negative for the four Ly49 markers tested (A, G2, C and I), even in TAP-deficient mice lacking the expression of peptide-dependent class I molecules.11 The functional significance of this, and whether these NKT cells are controlled by other inhibitory receptors, has yet to be determined. Our data suggest that inhibitory Ly49 receptors are displayed on some, but not all, subsets of NKT cells, and suggest that the expression of these receptors is finely tuned to the TCR. Several reports have demonstrated the functionality of Ly49 receptors on NKT cells, together demonstrating that to understand fully the regulation of NKT-cell activation and function, their complex expression of inhibitory receptors must be taken into consideration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Swedish Medical Research Council, the Swedish Rheumatism Association and the following foundations: Kungliga Fysiografiska Sällskapet, Greta och Johan Kocks stiftelser, Alfred Österlunds stiftelse, Magnus Bergwalls stiftelse, Crafoordska stiftelsen and Konung Gustaf V:s 80-årsfond and the Medical Faculty of Lund University to S. Cardell. M. Kronenberg and S. Sidobre were supported by the U. S. National Health grant RO1 CA52511. M. Sköld was supported by Stiftelsen Lars Hertas minne and the Medical Faculty at Lund University, and M. Stenström was supported by a fellowship from the Inflammation Programme of the Swedish Strategic Foundations.

Abbreviations

- DN

double negative

- αGC

α-galactosyl ceramide

- NKT

natural killer T

- tet

tetramer

References

- 1.Mendiratta SK, Martin WD, Hong S, Boesteanu A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L. CD1d1 mutant mice are deficient in natural T cells that promptly produce IL-4. Immunity. 1997;6:469–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smiley ST, Kaplan MH, Grusby MJ. Immunoglobulin E production in the absence of interleukin-4-secreting CD1-dependent cells. Science. 1997;275:977–9. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen YH, Chiu NM, Mandal M, Wang N, Wang CR. Impaired NK1+ T cell development and early IL-4 production in CD1-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:459–67. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Godfrey DI, Hammond KJ, Poulton LD, Smyth MJ, Baxter AG. NKT cells: facts, functions and fallacies. Immunol Today. 2000;21:573–83. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01735-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendelac A, Lantz O, Quimby ME, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR, Brutkiewicz RR. CD1 recognition by mouse NK1+ T lymphocytes. Science. 1995;268:863–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7538697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardell S, Tangri S, Chan S, Kronenberg M, Benoist C, Mathis D. CD1-restricted CD4+ T cells in major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:993–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagasawa R, Gross J, Kanagawa O, Townsend K, Lanier LL, Chiller J, Allison JP. Identification of a novel T cell surface disulfide-bonded dimer distinct from the alpha/beta antigen receptor. J Immunol. 1987;138:815–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortaldo JR, Winkler-Pickett R, Mason AT, Mason LH. The Ly-49 family: regulation of cytotoxicity and cytokine production in murine CD3+ cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:1158–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald RH, Lees RK, Held W. Developmentally regulated extinction of Ly-49 receptor expression permits maturation and selection of NK1.1+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2109–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lantz O, Sharara LI, Tilloy F, Andersson A, DiSanto JP. Lineage relationships and differentiation of natural killer (NK) T cells. Intrathymic selection and interleukin (IL) -4 production in the absence of NKR-P1 and Ly49 molecules. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1395–1401. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.8.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skold M, Cardell S. Differential regulation of Ly49 expression on CD4+ and CD4–CD8– (double negative) NK1.1+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2488–96. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2488::AID-IMMU2488>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda M, Lohwasser S, Yamamura T, Takei F. Regulation of NKT cells by Ly49: analysis of primary NKT cells and generation of NKT cell line. J Immunol. 2001;167:4180–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raulet DH, Held W, Correa I, Dorfman JR, Wu MF, Corral L. Specificity, tolerance and developmental regulation of natural killer cells defined by expression of class I-specific Ly49 receptors. Immunol Rev. 1997;155:41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long EO, Wagtmann N. Natural killer cell receptors. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:344–50. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Held W, Roland J, Raulet DH. Allelic exclusion of Ly49-family genes encoding class I MHC-specific receptors on NK cells. Nature. 1995;376:355–8. doi: 10.1038/376355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Held W, Kunz B. An allele-specific, stochastic gene expression process controls the expression of multiple Ly49 family genes and generates a diverse, MHC-specific NK cell receptor repertoire. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2407–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199808)28:08<2407::AID-IMMU2407>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ljunggren HG, Karre K. In search of the ‘missing self’: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition [see comments] Immunol Today. 1990;11:237–44. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Held W, Cado D, Raulet DH. Transgenic expression of the Ly49A natural killer cell receptor confers class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) -specific inhibition and prevents bone marrow allograft rejection. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2037–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahlen L, Oberg L, Brannstrom T, Khoo NK, Lendahl U, Sentman CL. Ly49A expression on T cells alters T cell selection. Int Immunol. 2000;12:215–22. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pauza M, Smith KM, Neal H, Reilly C, Lanier LL, Lo D. Transgenic expression of Ly-49A in thymocytes alters repertoire selection. J Immunol. 2000;164:884–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells. Development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng D, Dick M, Cheng L, Amano M, Dejbakhsh-Jones S, Huie P, Sibley R, Strober S. Subsets of transgenic T cells that recognize CD1 induce or prevent murine lupus: role of cytokines. J Exp Med. 1998;187:525–36. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SH, Roark JH, Bendelac A. Tissue-specific recognition of mouse CD1 molecules. J Immunol. 1998;160:3128–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behar SM, Podrebarac TA, Roy CJ, Wang CR, Brenner MB. Diverse TCRs recognize murine CD1. J Immunol. 1999;162:161–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron JL, Gardiner L, Nishimura S, Shinkai K, Locksley R, Ganem D. Activation of a nonclassical NKT cell subset in a transgenic mouse model of hepatitis B virus infection. Immunity. 2002;16:583–94. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SH, Weiss A, Benlagha K, Kyin T, Teyton L, Bendelac A. The mouse CD1d-restricted repertoire is dominated by a few autoreactive T cell receptor families. J Exp Med. 2001;193:893–904. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.8.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lanier LL. On guard – activating NK cell receptors. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:23–7. doi: 10.1038/83130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skold M, Faizunnessa NN, Wang CR, Cardell S. CD1d-specific NK1.1+ T cells with a transgenic variant TCR. J Immunol. 2000;165:168–74. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bieberich C, Scangos G, Tanaka K, Jay G. Regulated expression of a murine class I gene in transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:1339–42. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.4.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vugmeyster Y, Glas R, Perarnau B, Lemonnier FA, Eisen H, Ploegh H. Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I KbDb –/– deficient mice possess functional CD8+ T cells and natural killer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuda JL, Naidenko OV, Gapin L, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Wang CR, Koezuka Y, Kronenberg M. Tracking the response of natural killer T cells to a glycolipid antigen using CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;192:741–54. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanke T, Takizawa H, McMahon CW, et al. Direct assessment of MHC class I binding by seven Ly49 inhibitory NK cell receptors. Immunity. 1999;11:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Morris MA, Nguyen P, et al. Ly49I NK cell receptor transgene inhibition of rejection of H2b mouse bone marrow transplants. J Immunol. 2000;164:1793–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benlagha K, Weiss A, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. In vivo identification of glycolipid antigen-specific T cells using fluorescent CD1d tetramers. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1895–903. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.11.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–9. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coles MC, McMahon CW, Takizawa H, Raulet DH. Memory CD8 T lymphocytes express inhibitory MHC-specific Ly49 receptors. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:236–44. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200001)30:1<236::AID-IMMU236>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oberg L, Eriksson M, Fahlen L, Sentman CL. Expression of Ly49A on T cells alters the threshold for T cell responses. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2849–56. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200010)30:10<2849::AID-IMMU2849>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ikarashi Y, Mikami R, Bendelac A, et al. Dendritic cell maturation overrules H-2D-mediated natural killer T (NKT) cell inhibition: critical role for B7 in CD1d-dependent NKT cell interferon gamma production. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1179–86. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raulet DH, Vance RE, McMahon CW. Regulation of the natural killer cell receptor repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:291–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:971–8. doi: 10.1038/ni710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benlagha K, Kyin T, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. A thymic precursor to the NK T cell lineage. Science. 2002;296:553–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1069017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellicci DG, Hammond KJ, Uldrich AP, Baxter AG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A natural killer T (NKT) cell developmental pathway involving a thymus-dependent NK1.1(–) CD4(+) CD1d-dependent precursor stage. J Exp Med. 2002;195:835–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]